Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Globalization and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Complementarities

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Faculty of Management, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Johor, Malaysia, Department of Management, Mobarakeh Branch, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

Affiliation Applied Statistics Department, Economics and Administration Faculty, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Parisa Samimi,

- Hashem Salarzadeh Jenatabadi

- Published: April 10, 2014

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824

- Reader Comments

This study was carried out to investigate the effect of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC countries. Furthermore, the study examined the effect of complementary policies on the growth effect of globalization. It also investigated whether the growth effect of globalization depends on the income level of countries. Utilizing the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator within the framework of a dynamic panel data approach, we provide evidence which suggests that economic globalization has statistically significant impact on economic growth in OIC countries. The results indicate that this positive effect is increased in the countries with better-educated workers and well-developed financial systems. Our finding shows that the effect of economic globalization also depends on the country’s level of income. High and middle-income countries benefit from globalization whereas low-income countries do not gain from it. In fact, the countries should receive the appropriate income level to be benefited from globalization. Economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does so via complementary reforms.

Citation: Samimi P, Jenatabadi HS (2014) Globalization and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Complementarities. PLoS ONE 9(4): e87824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824

Editor: Rodrigo Huerta-Quintanilla, Cinvestav-Merida, Mexico

Received: November 5, 2013; Accepted: January 2, 2014; Published: April 10, 2014

Copyright: © 2014 Samimi, Jenatabadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The study is supported by the Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia, Malaysian International Scholarship (MIS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Globalization, as a complicated process, is not a new phenomenon and our world has experienced its effects on different aspects of lives such as economical, social, environmental and political from many years ago [1] – [4] . Economic globalization includes flows of goods and services across borders, international capital flows, reduction in tariffs and trade barriers, immigration, and the spread of technology, and knowledge beyond borders. It is source of much debate and conflict like any source of great power.

The broad effects of globalization on different aspects of life grab a great deal of attention over the past three decades. As countries, especially developing countries are speeding up their openness in recent years the concern about globalization and its different effects on economic growth, poverty, inequality, environment and cultural dominance are increased. As a significant subset of the developing world, Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries are also faced by opportunities and costs of globalization. Figure 1 shows the upward trend of economic globalization among different income group of OIC countries.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.g001

Although OICs are rich in natural resources, these resources were not being used efficiently. It seems that finding new ways to use the OICs economic capacity more efficiently are important and necessary for them to improve their economic situation in the world. Among the areas where globalization is thought, the link between economic growth and globalization has been become focus of attention by many researchers. Improving economic growth is the aim of policy makers as it shows the success of nations. Due to the increasing trend of globalization, finding the effect of globalization on economic growth is prominent.

The net effect of globalization on economic growth remains puzzling since previous empirical analysis did not support the existent of a systematic positive or negative impact of globalization on growth. Most of these studies suffer from econometrics shortcoming, narrow definition of globalization and small number of countries. The effect of economic globalization on the economic growth in OICs is also ambiguous. Existing empirical studies have not indicated the positive or negative impact of globalization in OICs. The relationship between economic globalization and economic growth is important especially for economic policies.

Recently, researchers have claimed that the growth effects of globalization depend on the economic structure of the countries during the process of globalization. The impact of globalization on economic growth of countries also could be changed by the set of complementary policies such as improvement in human capital and financial system. In fact, globalization by itself does not increase or decrease economic growth. The effect of complementary policies is very important as it helps countries to be successful in globalization process.

In this paper, we examine the relationship between economic globalization and growth in panel of selected OIC countries over the period 1980–2008. Furthermore, we would explore whether the growth effects of economic globalization depend on the set of complementary policies and income level of OIC countries.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section consists of a review of relevant studies on the impact of globalization on growth. Afterward the model specification is described. It is followed by the methodology of this study as well as the data sets that are utilized in the estimation of the model and the empirical strategy. Then, the econometric results are reported and discussed. The last section summarizes and concludes the paper with important issues on policy implications.

Literature Review

The relationship between globalization and growth is a heated and highly debated topic on the growth and development literature. Yet, this issue is far from being resolved. Theoretical growth studies report at best a contradictory and inconclusive discussion on the relationship between globalization and growth. Some of the studies found positive the effect of globalization on growth through effective allocation of domestic resources, diffusion of technology, improvement in factor productivity and augmentation of capital [5] , [6] . In contrast, others argued that globalization has harmful effect on growth in countries with weak institutions and political instability and in countries, which specialized in ineffective activities in the process of globalization [5] , [7] , [8] .

Given the conflicting theoretical views, many studies have been empirically examined the impact of the globalization on economic growth in developed and developing countries. Generally, the literature on the globalization-economic growth nexus provides at least three schools of thought. First, many studies support the idea that globalization accentuates economic growth [9] – [19] . Pioneering early studies include Dollar [9] , Sachs et al. [15] and Edwards [11] , who examined the impact of trade openness by using different index on economic growth. The findings of these studies implied that openness is associated with more rapid growth.

In 2006, Dreher introduced a new comprehensive index of globalization, KOF, to examine the impact of globalization on growth in an unbalanced dynamic panel of 123 countries between 1970 and 2000. The overall result showed that globalization promotes economic growth. The economic and social dimensions have positive impact on growth whereas political dimension has no effect on growth. The robustness of the results of Dreher [19] is approved by Rao and Vadlamannati [20] which use KOF and examine its impact on growth rate of 21 African countries during 1970–2005. The positive effect of globalization on economic growth is also confirmed by the extreme bounds analysis. The result indicated that the positive effect of globalization on growth is larger than the effect of investment on growth.

The second school of thought, which supported by some scholars such as Alesina et al. [21] , Rodrik [22] and Rodriguez and Rodrik [23] , has been more reserve in supporting the globalization-led growth nexus. Rodriguez and Rodrik [23] challenged the robustness of Dollar (1992), Sachs, Warner et al. (1995) and Edwards [11] studies. They believed that weak evidence support the idea of positive relationship between openness and growth. They mentioned the lack of control for some prominent growth indicators as well as using incomprehensive trade openness index as shortcomings of these works. Warner [24] refuted the results of Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000). He mentioned that Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000) used an uncommon index to measure trade restriction (tariffs revenues divided by imports). Warner (2003) explained that they ignored all other barriers on trade and suggested using only the tariffs and quotas of textbook trade policy to measure trade restriction in countries.

Krugman [25] strongly disagreed with the argument that international financial integration is a major engine of economic development. This is because capital is not an important factor to increase economic development and the large flows of capital from rich to poor countries have never occurred. Therefore, developing countries are unlikely to increase economic growth through financial openness. Levine [26] was more optimistic about the impact of financial liberalization than Krugman. He concluded, based on theory and empirical evidences, that the domestic financial system has a prominent effect on economic growth through boosting total factor productivity. The factors that improve the functioning of domestic financial markets and banks like financial integration can stimulate improvements in resource allocation and boost economic growth.

The third school of thoughts covers the studies that found nonlinear relationship between globalization and growth with emphasis on the effect of complementary policies. Borensztein, De Gregorio et al. (1998) investigated the impact of FDI on economic growth in a cross-country framework by developing a model of endogenous growth to examine the role of FDI in the economic growth in developing countries. They found that FDI, which is measured by the fraction of products produced by foreign firms in the total number of products, reduces the costs of introducing new varieties of capital goods, thus increasing the rate at which new capital goods are introduced. The results showed a strong complementary effect between stock of human capital and FDI to enhance economic growth. They interpreted this finding with the observation that the advanced technology, brought by FDI, increases the growth rate of host economy when the country has sufficient level of human capital. In this situation, the FDI is more productive than domestic investment.

Calderón and Poggio [27] examined the structural factors that may have impact on growth effect of trade openness. The growth benefits of rising trade openness are conditional on the level of progress in structural areas including education, innovation, infrastructure, institutions, the regulatory framework, and financial development. Indeed, they found that the lack of progress in these areas could restrict the potential benefits of trade openness. Chang et al. [28] found that the growth effects of openness may be significantly improved when the investment in human capital is stronger, financial markets are deeper, price inflation is lower, and public infrastructure is more readily available. Gu and Dong [29] emphasized that the harmful or useful growth effect of financial globalization heavily depends on the level of financial development of economies. In fact, if financial openness happens without any improvement in the financial system of countries, growth will replace by volatility.

However, the review of the empirical literature indicates that the impact of the economic globalization on economic growth is influenced by sample, econometric techniques, period specifications, observed and unobserved country-specific effects. Most of the literature in the field of globalization, concentrates on the effect of trade or foreign capital volume (de facto indices) on economic growth. The problem is that de facto indices do not proportionally capture trade and financial globalization policies. The rate of protections and tariff need to be accounted since they are policy based variables, capturing the severity of trade restrictions in a country. Therefore, globalization index should contain trade and capital restrictions as well as trade and capital volume. Thus, this paper avoids this problem by using a comprehensive index which called KOF [30] . The economic dimension of this index captures the volume and restriction of trade and capital flow of countries.

Despite the numerous studies, the effect of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC is still scarce. The results of recent studies on the effect of globalization in OICs are not significant, as they have not examined the impact of globalization by empirical model such as Zeinelabdin [31] and Dabour [32] . Those that used empirical model, investigated the effect of globalization for one country such as Ates [33] and Oyvat [34] , or did it for some OIC members in different groups such as East Asia by Guillaumin [35] or as group of developing countries by Haddad et al. [36] and Warner [24] . Therefore, the aim of this study is filling the gap in research devoted solely to investigate the effects of economic globalization on growth in selected OICs. In addition, the study will consider the impact of complimentary polices on the growth effects of globalization in selected OIC countries.

Model Specification

Methodology and Data

This paper applies the generalized method of moments (GMM) panel estimator first suggested by Anderson and Hsiao [38] and later developed further by Arellano and Bond [39] . This flexible method requires only weak assumption that makes it one of the most widely used econometric techniques especially in growth studies. The dynamic GMM procedure is as follow: first, to eliminate the individual effect form dynamic growth model, the method takes differences. Then, it instruments the right hand side variables by using their lagged values. The last step is to eliminate the inconsistency arising from the endogeneity of the explanatory variables.

The consistency of the GMM estimator depends on two specification tests. The first is a Sargan test of over-identifying restrictions, which tests the overall validity of the instruments. Failure to reject the null hypothesis gives support to the model. The second test examines the null hypothesis that the error term is not serially correlated.

The GMM can be applied in one- or two-step variants. The one-step estimators use weighting matrices that are independent of estimated parameters, whereas the two-step GMM estimator uses the so-called optimal weighting matrices in which the moment conditions are weighted by a consistent estimate of their covariance matrix. However, the use of the two-step estimator in small samples, as in our study, has problem derived from proliferation of instruments. Furthermore, the estimated standard errors of the two-step GMM estimator tend to be small. Consequently, this paper employs the one-step GMM estimator.

In the specification, year dummies are used as instrument variable because other regressors are not strictly exogenous. The maximum lags length of independent variable which used as instrument is 2 to select the optimal lag, the AR(1) and AR(2) statistics are employed. There is convincing evidence that too many moment conditions introduce bias while increasing efficiency. It is, therefore, suggested that a subset of these moment conditions can be used to take advantage of the trade-off between the reduction in bias and the loss in efficiency. We restrict the moment conditions to a maximum of two lags on the dependent variable.

Data and Empirical Strategy

We estimated Eq. (1) using the GMM estimator based on a panel of 33 OIC countries. Table S1 in File S1 lists the countries and their income groups in the sample. The choice of countries selected for this study is primarily dictated by availability of reliable data over the sample period among all OIC countries. The panel covers the period 1980–2008 and is unbalanced. Following [40] , we use annual data in order to maximize sample size and to identify the parameters of interest more precisely. In fact, averaging out data removes useful variation from the data, which could help to identify the parameters of interest with more precision.

The dependent variable in our sample is logged per capita real GDP, using the purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates and is obtained from the Penn World Table (PWT 7.0). The economic dimension of KOF index is derived from Dreher et al. [41] . We use some other variables, along with economic globalization to control other factors influenced economic growth. Table S2 in File S2 shows the variables, their proxies and source that they obtain.

We relied on the three main approaches to capture the effects of economic globalization on economic growth in OIC countries. The first one is the baseline specification (Eq. (1)) which estimates the effect of economic globalization on economic growth.

The second approach is to examine whether the effect of globalization on growth depends on the complementary policies in the form of level of human capital and financial development. To test, the interactions of economic globalization and financial development (KOF*FD) and economic globalization and human capital (KOF*HCS) are included as additional explanatory variables, apart from the standard variables used in the growth equation. The KOF, HCS and FD are included in the model individually as well for two reasons. First, the significance of the interaction term may be the result of the omission of these variables by themselves. Thus, in that way, it can be tested jointly whether these variables affect growth by themselves or through the interaction term. Second, to ensure that the interaction term did not proxy for KOF, HCS or FD, these variables were included in the regression independently.

In the third approach, in order to study the role of income level of countries on the growth effect of globalization, the countries are split based on income level. Accordingly, countries were classified into three groups: high-income countries (3), middle-income (21) and low-income (9) countries. Next, dummy variables were created for high-income (Dum 3), middle-income (Dum 2) and low-income (Dum 1) groups. Then interaction terms were created for dummy variables and KOF. These interactions will be added to the baseline specification.

Findings and Discussion

This section presents the empirical results of three approaches, based on the GMM -dynamic panel data; in Tables 1 – 3 . Table 1 presents a preliminary analysis on the effects of economic globalization on growth. Table 2 displays coefficient estimates obtained from the baseline specification, which used added two interaction terms of economic globalization and financial development and economic globalization and human capital. Table 3 reports the coefficients estimate from a specification that uses dummies to capture the impact of income level of OIC countries on the growth effect of globalization.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.t003

The results in Table 1 indicate that economic globalization has positive impact on growth and the coefficient is significant at 1 percent level. The positive effect is consistent with the bulk of the existing empirical literature that support beneficial effect of globalization on economic growth [9] , [11] , [13] , [19] , [42] , [43] .

According to the theoretical literature, globalization enhances economic growth by allocating resources more efficiently as OIC countries that can be specialized in activities with comparative advantages. By increasing the size of markets through globalization, these countries can be benefited from economic of scale, lower cost of research and knowledge spillovers. It also augments capital in OICs as they provide a higher return to capital. It has raised productivity and innovation, supported the spread of knowledge and new technologies as the important factors in the process of development. The results also indicate that growth is enhanced by lower level of government expenditure, lower level of inflation, higher level of human capital, deeper financial development, more domestic investment and better institutions.

Table 2 represents that the coefficients on the interaction between the KOF, HCS and FD are statistically significant at 1% level and with the positive sign. The findings indicate that economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does via complementary reforms. On the other hand, the positive effect of economic globalization can be significantly enhanced if some complementary reforms in terms of human capital and financial development are undertaken.

In fact, the implementation of new technologies transferred from advanced economies requires skilled workers. The results of this study confirm the importance of increasing educated workers as a complementary policy in progressing globalization. However, countries with higher level of human capital can be better and faster to imitate and implement the transferred technologies. Besides, the financial openness brings along the knowledge and managerial for implementing the new technology. It can be helpful in improving the level of human capital in host countries. Moreover, the strong and well-functioned financial systems can lead the flow of foreign capital to the productive and compatible sectors in developing countries. Overall, with higher level of human capital and stronger financial systems, the globalized countries benefit from the growth effect of globalization. The obtained results supported by previous studies in relative to financial and trade globalization such as [5] , [27] , [44] , [45] .

Table (3 ) shows that the estimated coefficients on KOF*dum3 and KOF*dum2 are statistically significant at the 5% level with positive sign. The KOF*dum1 is statistically significant with negative sign. It means that increase in economic globalization in high and middle-income countries boost economic growth but this effect is diverse for low-income countries. The reason might be related to economic structure of these countries that are not received to the initial condition necessary to be benefited from globalization. In fact, countries should be received to the appropriate income level to be benefited by globalization.

The diagnostic tests in tables 1 – 3 show that the estimated equation is free from simultaneity bias and second-order correlation. The results of Sargan test accept the null hypothesis that supports the validity of the instrument use in dynamic GMM.

Conclusions and Implications

Numerous researchers have investigated the impact of economic globalization on economic growth. Unfortunately, theoretical and the empirical literature have produced conflicting conclusions that need more investigation. The current study shed light on the growth effect of globalization by using a comprehensive index for globalization and applying a robust econometrics technique. Specifically, this paper assesses whether the growth effects of globalization depend on the complementary polices as well as income level of OIC countries.

Using a panel data of OIC countries over the 1980–2008 period, we draw three important conclusions from the empirical analysis. First, the coefficient measuring the effect of the economic globalization on growth was positive and significant, indicating that economic globalization affects economic growth of OIC countries in a positive way. Second, the positive effect of globalization on growth is increased in countries with higher level of human capital and deeper financial development. Finally, economic globalization does affect growth, whether the effect is beneficial depends on the level of income of each group. It means that economies should have some initial condition to be benefited from the positive effects of globalization. The results explain why some countries have been successful in globalizing world and others not.

The findings of our study suggest that public policies designed to integrate to the world might are not optimal for economic growth by itself. Economic globalization not only directly promotes growth but also indirectly does so via complementary reforms.

The policy implications of this study are relatively straightforward. Integrating to the global economy is only one part of the story. The other is how to benefits more from globalization. In this respect, the responsibility of policymakers is to improve the level of educated workers and strength of financial systems to get more opportunities from globalization. These economic policies are important not only in their own right, but also in helping developing countries to derive the benefits of globalization.

However, implementation of new technologies transferred from advanced economies requires skilled workers. The results of this study confirm the importance of increasing educated workers as a complementary policy in progressing globalization. In fact, countries with higher level of human capital can better and faster imitate and implement the transferred technologies. The higher level of human capital and certain skill of human capital determine whether technology is successfully absorbed across countries. This shows the importance of human capital in the success of countries in the globalizing world.

Financial openness in the form of FDI brings along the knowledge and managerial for implementing the new technology. It can be helpful in upgrading the level of human capital in host countries. Moreover, strong and well-functioned financial systems can lead the flow of foreign capital to the productive and compatible sectors in OICs.

In addition, the results show that economic globalization does affect growth, whether the effect is beneficial depends on the level of income of countries. High and middle income countries benefit from globalization whereas low-income countries do not gain from it. As Birdsall [46] mentioned globalization is fundamentally asymmetric for poor countries, because their economic structure and markets are asymmetric. So, the risks of globalization hurt the poor more. The structure of the export of low-income countries heavily depends on primary commodity and natural resource which make them vulnerable to the global shocks.

The major research limitation of this study was the failure to collect data for all OIC countries. Therefore future research for all OIC countries would shed light on the relationship between economic globalization and economic growth.

Supporting Information

Sample of Countries.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.s001

The Name and Definition of Indicators.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087824.s002

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: PS. Performed the experiments: PS. Analyzed the data: PS. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: PS HSJ. Wrote the paper: PS HSJ.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. Bhandari AK, Heshmati A (2005) Measurement of Globalization and its Variations among Countries, Regions and over Time. IZA Discussion Paper No.1578.

- 3. Collins W, Williamson J (1999) Capital goods prices, global capital markets and accumulation: 1870–1950. NBER Working Paper No.7145.

- 4. Obstfeld M, Taylor A (1997) The great depression as a watershed: international capital mobility over the long run. In: D M, Bordo CG, and Eugene N White, editors. The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press: NBER Project Report series. 353–402.

- 7. De Melo J, Gourdon J, Maystre N (2008) Openness, Inequality and Poverty: Endowments Matter. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No.3981.

- 8. Berg A, Krueger AO (2003) Trade, growth, and poverty: a selective survey. IMF Working Papers No.1047.

- 16. Barro R, Sala-i-Martin X (2004) Economic Growth. New York: McGraw Hill.

- 21. Alesina A, Grilli V, Milesi-Ferretti G, Center L, del Tesoro M (1994) The political economy of capital controls. In: Leiderman L, Razin A, editors. Capital Mobility: The Impact on Consumption, Investment and Growth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 289–321.

- 22. Rodrik D (1998) Who needs capital-account convertibility? In: Fischer S, editor. Should the IMF Pursue Capital Account Convertibility?, Essays in international finance. Princeton: Department of Economics, Princeton University. 55–65.

- 25. Krugman P (1993) International Finance and Economic Development. In: Giovannini A, editor. Finance and Development: Issues and Experience. Cambridge Cambridge University Press. 11–24.

- 27. Calderón C, Poggio V (2010) Trade and Economic Growth Evidence on the Role of Complementarities for CAFTA-DR Countries. World Bank Policy Research, Working Paper No.5426.

- 30. Samimi P, Lim GC, Buang AA (2011) Globalization Measurement: Notes on Common Globalization Indexes. Knowledge Management, Economics and Information Technology 1(7).

- 36. Haddad ME, Lim JJ, Saborowski C (2010) Trade Openness Reduces Growth Volatility When Countries are Well Diversified. Policy Research Working Paper Series NO. 5222.

- 37. Mammi I (2012) Essays in GMM estimation of dynamic panel data models. Lucca, Italy: IMT Institute for Advanced Studies.

- 41. Dreher A, Gaston N, Martens P (2008) Measuring globalisation: Gauging its consequences: Springer Verlag.

- 42. Brunner A (2003) The long-run effects of trade on income and income growth. IMF Working Papers No. 03/37.

- 44. Alfaro L, Chanda A, Kalemli-Ozcan S, Sayek S (2006) How does foreign direct investment promote economic growth? Exploring the effects of financial markets on linkages. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

- 46. Birdsall N (2002) A stormy day on an open field: asymmetry and convergence in the global economy. In: Gruen D, O'Brien T, Lawson J, editors. Globalisation, living standards and inequality. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia and Australian. 66–87.

- 47. Solt F (2009) Standardizing the World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly 90: 231–242 SWIID Version 233.230, July 2010.

- 48. Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2009) Financial Institutions and Markets across Countries and over Time. Policy Research Working Paper No.4943.

How our interconnected world is changing

Globalization isn’t going away, but it is changing, according to recent research from the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). In this episode of The McKinsey Podcast , MGI director Olivia White speaks with global editorial director Lucia Rahilly about the flows of goods, knowledge, and labor that drive global integration—and about what reshaping these flows might mean for our interconnected future.

After, global brewer AB InBev has flourished in the throes of what its CFO Fernando Tennenbaum describes as the recent “twists and turns.” Find out how in this excerpt from “ How to thrive in a downturn: A CFO perspective ,” recorded in December 2022 as part of our McKinsey Live series. 1 Please note that market conditions may have changed since this interview was conducted in December 2022.

The McKinsey Podcast is cohosted by Roberta Fusaro and Lucia Rahilly.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Globalization is here to stay

Lucia Rahilly: Pundits and other public figures have wrongly predicted the demise of globalization for what seems like years. Now, given the war in Ukraine and other disruptions, many are once again sounding its death knell. What does this new MGI research tell us about the fate of globalization? Is it really in retreat?

Olivia White: The flows of goods, the real tangible stuff, have leveled off after nearly 20-plus years of growing at twice the rate of GDP. But the flows of goods kept pace with GDP and even rose a little bit, surprisingly, in the past couple of years. Since GDP has been growing, that means actual ties have gotten stronger.

One of the most striking findings from this research was that flows representing knowledge and know-how, such as IP and data, and flows of services and international students have accelerated and are now growing faster than the flow of goods. Flows of data grew by more than 40 percent per annum over the past ten years.

Lucia Rahilly: Goods are a smaller share of total flows, a smaller share of economic output, than in the past. That doesn’t necessarily sound like a bad thing. Could it be a sign of progress?

Olivia White: The fact that certain goods are growing less quickly than other types of flows shows this shift in our economy and what’s most important to the way the economy functions. It comes on the back of a long history of different factors that influence growth and shifts in the way patterns work. What’s happening, in part, is that a variety of countries are producing more domestically—first and foremost China. That has been driving a lot of the flow down, if you take the longitudinal view, over the past ten years versus before.

The world remains interdependent

Lucia Rahilly: How interdependent would you say we are at this stage? Could you give us some examples of the ways we’re interconnected?

Olivia White: The top line is, every region in the world depends on another significant region for at least 25 percent of a flow it values most.

In general, regions that are manufacturing regions—Europe, Asia–Pacific, and China, if we look at it on its own because it’s such a large economy—depend very strongly on the rest of the world for resources: food to some degree, but really energy and minerals of different sorts. I’ll give you a few examples.

In general, regions that are manufacturing regions depend very strongly on the rest of the world for resources: food to some degree, but really energy and minerals. Olivia White

China imports over 25 percent of its minerals, from places as far-flung as Brazil, Chile, and South Africa. China imports energy, particularly in the form of oil from the Middle East and Russia. Europe is emblematic of these forms of dependency on energy. It was dependent on Russia for over 50 percent of its energy, but now that has drastically changed.

In some other regions in the world—places that are resource rich, like the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America—those places are highly dependent on the rest of the world for their manufactured goods. Well over half the world’s population lives in those places. They import well over 50 percent of their electronics and similar amounts of their pharmaceuticals. They are highly dependent on other parts of the world for things that are really quite critical to development and for modern life.

North America is somewhat of a different story. We don’t have any single spot of quite as great a dependency, at least at the broad category level. We import close to 25 percent of what we use in net value terms across the spectrum, both of resources and of manufactured goods.

This doesn’t yet speak of data and IP, where, for example, the US and Europe are fairly significant producers/exporters. A country like China is a very large consumer of IP.

Lucia Rahilly: How interdependent are we in terms of the global workforce?

Olivia White: This is quite striking. We asked how many workers in regions outside North America serve North American demand. And we asked the same question for Europe. It turns out that 60 million people in regions outside North America serve North American demand, and in Europe the corresponding number is 50 million.

These numbers are very substantial versus the working populations in those countries. So when you consider how much of what North Americans or Europeans are consuming could be produced onshore, by onshore labor, the answer is not even remotely close to those sorts of numbers—at least given the means of production or the way services are delivered today and the role people play in that.

Lucia Rahilly: Let’s turn to some of the categories of flows that have increased in recent years. What’s driving growth in global flows now that the trade in goods has stabilized?

Olivia White: Flows linked to knowledge and know-how. Knowledge services that have historically grown more slowly than manufactured goods and resources, with increased global connection over time, have flipped over the past ten years.

Professional services, such as engineering services, are among those more traditional trade flows that have been growing fastest, at about 6 percent a year, versus resources, which have slowed to just around two percent. Anything that involves real know-how—engineering, but also providing, say, call center support—is in that category.

The flows of IP are growing even faster. Now, IP is tricky because accounting for it is a very tricky thing to do. But it roughly looks at flows of the fun stuff. In the report we talk about Squid Game , but IP also includes movies, streaming platforms, music, and any sort of cultural elements that we consume.

It’s also important to consider flows of patents and ideas and the way countries or companies will use ideas or know-how developed in one country to help what they do broadly across the world. Those flows have been growing at roughly 6 percent per year as well.

There are data flows—the flows of packets of data. For example, if we were in different countries while conducting this interview there would be the flows between us. There are also flows linked to our ever-expanding use of cloud and data localization. Data transfer is happening more and more quickly.

The flows of international students have also been rising. That was mightily interrupted by the pandemic, for reasons I don’t need to belabor, but these flows seem to be rebounding. It’s important to consider the degree to which those will jump back on their accelerated growth trajectory.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

How covid-19 has affected global flows.

Lucia Rahilly: You mentioned flows of international students dropping off during COVID, for the obvious reasons. Did other flows generally drop off during the pandemic? Or were there examples of flows that were particularly resilient throughout that period?

Olivia White: There’s some variation, but many flows were remarkably resilient—resilient in a way that’s a bit counter to the general narrative about what happened during the pandemic.

The flows of resources and manufactured goods jumped reasonably significantly in 2020 and 2021, both to levels of about 6 percent per year on an annualized basis. To some degree, what was happening is that cross-border flows stepped in to replace interrupted domestic production. Flows from Asia came in, for example, to the US or to Europe. We’ve seen some flows go in reverse directions. There was a bunch of interruption in domestic production, which was quite surprising.

Flows of capital also jumped quite a lot as people needed to shift the way they were financing themselves. Multinationals needed to shift the way they were financing themselves. Some were moving liquidity to different parts of the world under times of financial stress. But those jumped to levels of growth in the tens of digits from what had actually been reversed growth for the past ten years. All those things jumped. IP jumped a little bit; data remained high. So these flows have been remarkably resilient.

The good and bad news about resource concentration

Lucia Rahilly: You invoked concentration a bit when you talked about Europe being dependent on Russia for 50 percent of its energy. Can you say a bit more about what concentration means in this context and how it affects the dynamics of the way we’re connected globally?

Olivia White: From the global perspective, there are some products that truly originate in only a few places in the world, and all of us across the globe are dependent on those few places for our supply. Iron ore is quite concentrated, and cobalt is concentrated in the DRC [Democratic Republic of the Congo].

The second type of concentration is viewed from the standpoint of an individual country. Lucia, you talked about Europe and gas dependency.

For example, Germany was getting gas from only a very concentrated set of sources. These are places where, for a variety of reasons, countries have built up dependencies on just a small number of other countries.

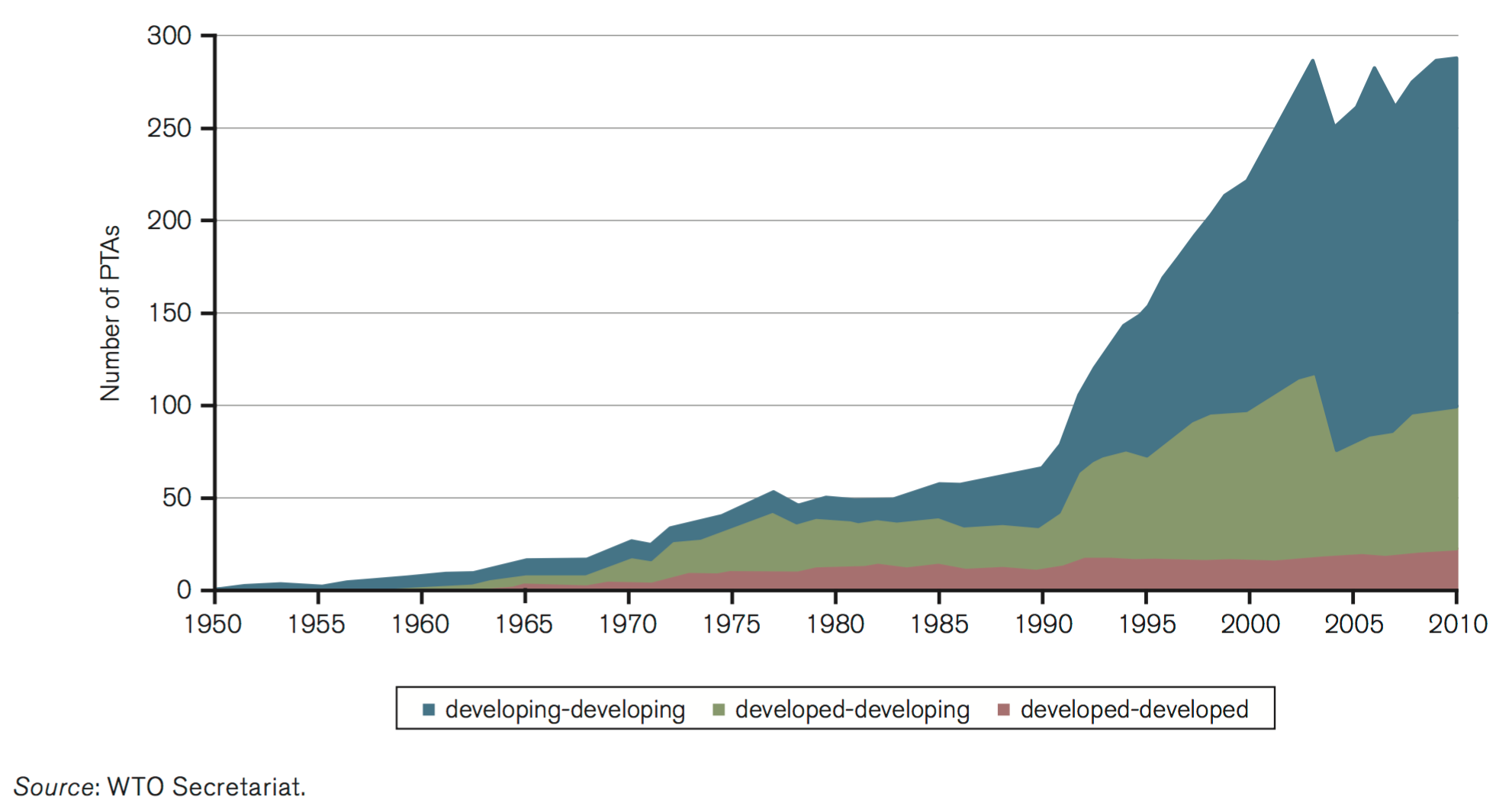

Why has this happened? Why are we in this position? Cost is one reason. People have made decisions based on economic factors. Another reason is regional preference. Not all goods are created equal, even if they fall in the same category.

The third reason is preferential trade agreements between different countries or other forms of tariffs or taxes that shape the way flows occur. We’re in a world in which suddenly people are realizing they have to contemplate the consequences associated with concentration—not of suppliers, but of the country of origin from which they’re buying things.

Lucia Rahilly: It sounds like concentration also increases efficiency in some cases where those disruptions don’t occur. Is concentration always a bad thing? If we rethink concentration, can we expect to see some loss of efficiency in the interim?

Olivia White: No, it’s not always a bad thing. But there are a lot of considerations to make that involve costs, involve geopolitical relationships, involve the role that various countries want to play themselves, how they’re thinking about development, how they’re thinking about their workforces. All those things have to be part of the mix.

Imagine three or four different countries, each with three trading partners, and they’re largely different trading partners. Swapping off who’s supplied by whom is a huge problem of coordination.

How global chains will evolve

Lucia Rahilly: Geopolitical risks have obviously trained a policy spotlight on reimagining these global value chains, whether for security reasons or to strengthen resilience more generally. Accepting that the world remains interdependent, how do we see trade flows continuing to evolve in coming years?

Olivia White: Broadly speaking, there are four categories of potential evolution. Semiconductors are most prominent in public discussion. Electronics, more broadly, is one of the fastest-moving value chains since 1995, with 21 percentage points of share movement per decade. Pharmaceuticals and the mining of critical minerals are other examples. And they will be part of what shifts the way that flows crisscross the globe.

Second category: textiles and apparel. This category is not as sensitive in a geopolitical sense as some of the things I was talking about before. This category is one where you actually do have new hub creation right now. Consumer electronics, other forms of electric equipment that aren’t particularly sensitive, possibly fall in that category too.

Third category: IT services and financial intermediation or professional services. That will reconfigure the ways in which services flow.

Fourth and finally, there’s the stuff that’s just going to be steady—food and beverages, paper and printing. There’s no particular reason to expect that there are strong forcing mechanisms that will change the way those things are flowing across the world right now. They’re things that have remained relatively steady for the past ten or more years.

Global flows are necessary for a net-zero transition

Lucia Rahilly: Do we have a view on whether the evolving state of global flows is helping or hindering the net-zero transition ?

Olivia White: The way I’d put it is, there is no way we move quickly toward a net-zero transition without global flows. There are certainly things about global flows that are tricky from a net-zero perspective. It costs carbon to ship things and move things a long way. But in order for net zero to be attainable, we need to make sure that energy-generating technologies and fuels are able to flow across the world.

Energy-generating technologies include both the minerals that underpin construction of those technologies and the actual manufacturing. So, in the first category, think nickel and lithium. In the second category, think about the actual manufacturing of solar panels. The minerals themselves are processed in only a few countries around the world. So people are going to have to move them from one place to another. Maybe the world could have broader diversification of such things, but on average, the timeline from discovering a mineral to being able to produce it at scale is well in excess of 16 years. If we want to move fast, we have the luxury to move things across the world. Meeting cost curves for manufacturing at scale and in locations where you have at least some established presence is going to be important.

The final element that’s crucial with respect to net zero is cross-border capital flows. It’s really important that developing countries are able to finance shifts in the way that energy is produced and consumed in their countries, which means they may have to both spend more, at least as a ratio of GDP, and have less ability to spend, given other forms of development imperative.

Multinationals and global resilience

Lucia Rahilly: What’s the role of major multinational companies as we look ahead toward reimagining the future of our global connectedness?

Olivia White: The first thing that needs to be recognized is that major multinational corporations play an outsize role in global flows today. Multinationals are responsible for about 30 percent of trade. They’re responsible for 60 percent of exports and 82 percent of exports of knowledge-intensive goods. So they disproportionately drive flows, especially the ones associated with knowledge. And therefore, they’re going to be the center of managing for their own resilience, but also in a collective sense, for the resilience of the world.

The future of global flows

Lucia Rahilly: The media tends to focus on what some see as globalization’s imminent demise. Accepting that global ties continue to bind and connect us across the world, it’s also natural for folks to have pretty strong reactions to these intense and ongoing global disruptions that we’ve experienced in recent years. How would you sum up the way we think about the future of globalization at a high level?

Olivia White: The world we live in right now is highly dependent on flows. Will those flows reconfigure and shift? Yes, absolutely. They have in the past, and they will in the future.

Lucia Rahilly: Do we see anything in the research to indicate that the world is actually moving toward decoupling, which is also very much part of the media narrative?

Olivia White: If you look along regional lines, individual regions can’t be independent. If you just start to play with what sorts of decoupling of regions would be possible, you see very quickly that it’s not something you can do.

Now, is it possible that you would get groups of countries that become more strongly interconnected among themselves and less strongly connected with others? Absolutely. It’s possible to move in that direction. The question becomes, is there an actual decoupling, or do you just have a shift in degree? As with most things in the world, the answer tends toward the shift in degree rather than an abrupt or sharp true change or decoupling.

Lucia Rahilly: Does greater regionalization improve resilience?

Olivia White: To some degree you can say, “Look, if I’m self-sufficient, I’m more resilient.” On the other hand, all of a sudden you depend on yourself for everything, and that’s a point of vulnerability in the same way that getting it only from one other person would be a problem.

There are a whole host of reasons some degree of regionalization might help. You’ve got things closer to you. But dependency just on a few sets of people, whether or not they’re in your region, means you’ve got dependency on just a few points of potential weaknesses rather than a broad web, which in general is a more resilient and robust structure.

Lucia Rahilly: Thanks so much, Olivia. That was such an interesting discussion.

Olivia White: A real pleasure, Lucia. Thank you.

Roberta Fusaro: One example of resilience is AB InBev. Here to talk about how it’s prospering in the face of worldwide disruption is its CFO, Fernando Tennenbaum. This excerpt, “ How to thrive in a downturn: A CFO perspective ,” from our McKinsey Live series, was recorded in December 2022.

Lucia Rahilly: Fernando, we’re confronting an unusual constellation of disruptions: inflation, high interest rates driving up the cost of capital, geopolitical turbulence unexpectedly upending supply chains and sending energy prices spiking—it’s genuinely a volatile moment. Tell us, how is AB InBev faring in the current context?

Fernando Tennenbaum: We’re fortunate to be in a resilient category. Despite these twists and turns in different parts of the world, beer sales have been quite strong. That said, inflation has turned out to be much higher than expected. 2 Market conditions may have changed since this interview was conducted. We need to ensure our operations are in sync with the market, to meet this unique moment. We need to understand the state of the consumer and adjust our operations accordingly.

In emerging markets like Latin America and Africa, inflation is not new news. There are different levels of inflation, but inflation has been a part of these economies for a very long time. Consumers are more used to it, companies are more used to it—and it’s probably a more straightforward discussion.

Lucia Rahilly: You’ve spent much of your career in Latin America where, as you said, inflation has historically been much higher and more volatile than in the US or in Western Europe. Walk us through some of the lessons that we in the US, for example, could learn from.

Fernando Tennenbaum: Make sure that you’re always looking at your customers, and that you’re always keeping up with inflation. You should avoid lagging too much, and you should avoid overpricing compared with inflation. If you do too little or too much, you start disturbing the health of the consumer. If you get it right, it’s probably a good thing for the business. You have to make sure you navigate the rising cost environment while ensuring that the consumer is in a good place, your product is in a good place, and the category is a healthy one. It’s a balancing act.

You should avoid lagging too much, and you should avoid overpricing compared with inflation. If you do too little or too much, you start disturbing the health of the consumer. Fernando Tennenbaum

Lucia Rahilly: AB InBev has a diverse portfolio of brands. Volumes are good. Are customers trading up or down, during this period, between your premium and mass-market brands?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Premiumization continues to be a trend, and consumers continue to trade up to premium brands. Over the course of this year, people often asked whether consumers were trading down—and we see no evidence of trading down. That is true for the US, that is true for Africa, and that is true for Latin America—which is quite unique.

I don’t know if the future will be different; the world is changing so fast. But if you were to ask me ten years from now, I’d expect premium to be even bigger than it is today.

Lucia Rahilly: Let’s talk about uncertainty. The economy could play out in many different ways. How do you manage for that?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Let’s take our debt portfolio. Now is the moment that interest rates are going up. Inflation and borrowing are going up. Overall, this tends to be bad news—but for us, it’s quite the opposite because we don’t have any debt maturing in the next three years. We prepared for this when we saw the world going to a very different place at the beginning of 2020.

We ended up raising some long-term debt and repaying all our short-term debt. Now we’re left with a debt portfolio that has an average maturity of 16 years and no meaningful amount of debt maturing in the next three years—all at a fixed rate. Since we don’t need to refinance, we’re actually buying back our debt. Rising interest rates can be good when you can buy back debt cheaper than it cost to issue.

Lucia Rahilly: You became CFO at AB InBev in 2020, when pandemic uncertainty was at its peak. Talk to us about how you navigated that period.

Fernando Tennenbaum: The first thing we did in 2020 was pump up our cash position. Not that we needed it, but I felt it would give operations peace of mind. To be prepared, we started borrowing a lot of money. And we started taking care of our people. We needed to make sure our people were safe—that was priority number one.

Once we made sure our employees were safe, our operations were safe, then we looked at opportunities and started to fast-forward. I remember we looked at May, for example, and started to see a lot of markets doing well in terms of volume. We had a lot of cash. We started buying back some debt, especially near-term debt, to create even more optionality for the future.

We also accelerated our digital transformation. The moment was uniquely suited for it. Digital was a much better way to reach customers at a time when everybody was afraid to meet in person. In hindsight, the company ended up in a much better place today than it was three years ago—in terms of our portfolio, our digital transformation, and even financially—because we acted very quickly and created a lot of optionality during the first few months of the pandemic.

Lucia Rahilly: Any mistakes to avoid?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Looking back, I wouldn’t have done anything massively different. If I had known the outcome, I might have done things differently. But without knowing the outcome, I felt that the way we managed and the optionality we created set us up well.

Lucia Rahilly: Brewing is such an agriculturally dependent business, and agriculture has been significantly disrupted, both because of the war in Ukraine and because of climate-related risk. As CFO, how do you think about sustainability in terms of longer-term value creation?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Sustainability cuts across the whole of our business. We have a lot of local suppliers—20,000 local farmers. Our brewing processes are natural. The more efficient we are there, the more sustainable we are and, actually, the more profitable we are. We have local operations, and we sell to the local community. And most of our customers are very small entrepreneurs. The more we help them, the better they can run their business. And we say beer is inclusive because we have two billion consumers.

Lucia Rahilly: Is packaging also part of the sustainability approach?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Definitely. For example, we have returnable glass bottles. That’s very efficient, very sustainable, and from an economic standpoint, that’s probably the most profitable packaging we have. It’s also the most affordable for consumers. So it’s good for us, good for the environment, and good for the consumers.

Lucia Rahilly: You said beer is inclusive in part because so many of us drink it. How else do you approach inclusion at AB InBev?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Our two billion consumers are very different from one another. We need to make sure that, as a company, we reflect our consumers. Whenever we look at our colleagues, we need to make sure they reflect the societies where we operate—and we operate in very different societies.

A diverse and inclusive team is going to be a better team. That also applies to our suppliers. For example, if you think about suppliers in Africa, some are very poor. They manage to get access to technology, which means we can track whether they’re receiving the funds we pay them. We can track where agricultural commodities are being sourced. So how we financially empower them is also a very important part of our sustainability strategy.

Lucia Rahilly: Looking ahead, how are you thinking about innovation and investment in technology, in order to enable growth?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Innovation is a key component of beer, and there are two sides to that. One is innovation in products. The other is packaging. In Mexico, for example, we have different pack sizes for different consumption occasions and consumer needs.

Beyond that, there’s also technological innovation. Take our B2B platform, which we started piloting in 2019. Now, three or four years later, we have around $30 billion of GMV [gross merchandise value] in our e-commerce platform, which is accessible in more than 19 countries. That’s the optimal portfolio to improve customer engagement at their point of sale. Before we launched our B2B platform, we used to spend seven minutes per week interacting with our customers. Today, with our B2B platform, we interact with them 30 minutes per week. We increased the number of points of sales. For example, in Brazil, we used to have 700,000 customers, and now we have more than a million customers. Previously, they were buying our products from a distributor. Now we can reach them directly with the B2B system in place.

This connection with our customers means we can do a lot of other things, like our online marketplace, where third-party products generated an annualized GMV of $850 million, up from zero four years ago. That marketplace now continues to grow and to deliver a lot of value for our customers and for ourselves.

Lucia Rahilly: One more question: If you could give one piece of advice to a brand-new CFO of a large, multinational corporation, what would it be in this market?

Fernando Tennenbaum: Make sure you plan for different scenarios. The world is moving very fast, and you can’t expect it to unfold in a certain way. But if you have options, are agile in making decisions, and have a very engaged team, then regardless of the twists and turns, you are able to meet the moment. And you are definitely able to deliver on your objectives.

Lucia Rahilly: I lied. I’m going to ask you one more. How do you see, for these new CFOs, the relationship between sustainability and inclusivity and growth? Do you see those in tension?

Fernando Tennenbaum: There is this myth that you are either sustainable or profitable. At least at AB InBev, we’re sure they go hand in hand. The more sustainable you are, the more profitable you are, and the more value you create for your different stakeholders.

Fernando Tennenbaum is the CFO of Anheuser-Busch InBev. Olivia White is a director of the McKinsey Global Institute and a senior partner in McKinsey’s Bay Area office. Roberta Fusaro is an editorial director in the Waltham, Massachusetts, office, and Lucia Rahilly is global editorial director and deputy publisher of McKinsey Global Publishing and is based in the New York office.

Comments and opinions expressed by interviewees are their own and do not represent or reflect the opinions, policies, or positions of McKinsey & Company or have its endorsement.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Global flows: The ties that bind in an interconnected world

On the cusp of a new era?

Globalization’s next chapter

Globalization and Economic Growth

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 14 April 2021

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ishak Demir 7 , 10 ,

- Mehmet Canakci 8 &

- Taha Egri 9

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

552 Accesses

1 Citations

Economic Growth , Integration and growth , Economic development.

Definitions

Globalization, or the increased interconnectedness and interdependence of peoples, companies, institutions and countries. It is generally understood to include two inter-related elements: the opening of international borders to increasingly fast flows of goods, services, finance, investment, people, information, ideas and technology; and the changes in institutions and policies at national and international levels that facilitate or promote such flows (WHO 2020 ). Globalization process has impacts on economies, prosperity, development of societies, political systems, environment, and cultures around the world.

Economic globalization can be defined as the increasing interdependence of world economies as a result of the growing scale of cross-border trade of commodities and services, flow of international capital and wide and rapid spread of technologies. It reflects the continuing expansion and mutual...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Alesina A et al (1994) The political economy of capital controls. In: Leiderman L, Razin A (eds) Capital mobility: the impact on consumption, investment and growth. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 289–321

Google Scholar

Bauman Z (1998) Globalization the human consequences. Columbia University Press, New York

Berger PL (1997) Four faces of global culture. Nat Int 49:23–29

Brenner N (1999) Beyond state-centrism? Space, territoriality, and geographical scale in globalization studies. Theory Soc 28(1):39–78

Article Google Scholar

Castells M (2000) Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society. Br J Soc 51(1):5–24

Demirguc-Kunt A, Levine R (2008) Finance, financial sector policies, and long-run growth. The World Bank

Dollar D (1992) Outward-oriented developing economies really do grow more rapidly: evidence from 95 LDCs. Econ Dev Cult Chang 40(3):523–544

Dowrick S, DeLong JB (2003) Globalization and convergence. In: Bordo MD et al (eds) Globalization in historical perspective. University of Chicago Press, pp 191–226

Dreher A (2006) Does globalization affects growth? Empirical evidence from a new index. Appl Econ 38(10):1091–1110

Easterly W (2004) Channels from globalization to inequality: productivity world vs factor world. Paper presented at the Brookings Trade Forum on Globalization, Poverty and Inequality, 13–14 May, Washington, DC

Edwards S (1998) Openness, productivity and growth: what do we really know? Econ J 108:383–398

Edwards S (2005) Capital controls, sudden stops, and current account reversals. NBER Working Paper No. 11170. https://www.nber.org/papers/w11170.pdf . Accessed 15 May 2020

Falk R (1999) Predatory globalization: a critique. Polity Press, Cambridge

Fouquin M, Hugot J (2016) Two centuries of bilateral trade and gravity data: 1827–2014. CEPII Working Paper, 2016–14. http://www.cepii.fr/pdf_pub/wp/2016/wp2016-14.pdf . Accessed 15 May 2020

Frankel JA, Romer DH (1999) Does trade cause growth? Am Econ Rev 89(3):379–399

Gao S (2000) Economic globalization: trends, risks and risk prevention. CDP Background Papers 001, United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs

Georgantzas N, Katsamakas E, Solowiej D (2010) Giddens’ globalization: exploring dynamic implications. Syst Res Behav Sci 27(6):622–638

Giddens A (1990) Consequences of modernity. Standford University Press, Standford

Gilpin R (2000) The challenge of global capitalism: the world economy in the 21 st century. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Book Google Scholar

Gu XH, Dong BM (2011) A theory of financial liberalisation: why are developing countries so reluctant? World Econ 34:1106–1123

Held D et al (1999) Global transformations: politics, economics and cultures. Polity Press, Cambridge

Hernández RA (2003) Neoclassical and endogenous growth models: theory and practice. Warwick University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.5069.1600

Hirst P, Thompson G (2001) Globalization in question: the international economy and the possibilities of governance

Intriligator MD (2004) Globalization of the world economy: potential benefits and costs and a net assessment. J Policy Model 26(4):485–498

Lane DC, Husemann E (2008) Steering without Circe: attending to reinforcing loops in social systems. Syst Dyn Rev 24(1):27–61

Levine R (2001) International financial liberalization and economic growth. Rev Int Econ 9:688–702

Luhmann N (1982) The world society as a social system. Int J Gen Syst 8(3):131–138

Nissanke M, Thorbecke E (2007) The impact of globalization on the world’s poor: transmission mechanisms. Palgrave Macmillan

Nye J (2002) The paradox of American power: why the world’s only superpower can’t go it alone. Oxford University Press, New York

OECD (2002) Foreign direct investment for development: maximising benefits, minimising costs. OECD Publications

Rodriguez F, Rodrik D (2000) Trade policy and economic growth: a sceptic’s guide to the cross-national evidence. NBER Mac Ann 15:261–325

Stiglitz J (2003) Globalization and growth in emerging markets and the new economy. J Policy Model

Stiglitz J (2007) Making globalization work. Penguin Books, New York

Wallerstein I (2016) The scholarly mainstream and reality: we at a turning point. In: Wallerstein I (ed) Modern world-system in the longue Duree. Routledge, London\New York

World Health Organizations (2020) www.who.int/topics/globalization/en (visited on 25.05.2020)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK

Ishak Demir

Inonu University, Battalgazi/Malatya, Turkey

Mehmet Canakci

Kirklareli University, Merkez/Kırklareli, Turkey

Ekonomi Arastirmalari Platformu, Istanbul, Turkey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ishak Demir .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience & Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

HAW Hamburg, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Amanda Lange Salvia

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Polimoda Fashion Institute, Florence, Italy

Marco Tortora

Fair Association, Florence, Italy

School of Economics and Management, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Demir, I., Canakci, M., Egri, T. (2021). Globalization and Economic Growth. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Decent Work and Economic Growth. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71058-7_90-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71058-7_90-1

Received : 29 May 2020

Accepted : 29 May 2020

Published : 14 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-71058-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-71058-7

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Trade and Globalization

How did international trade and globalization change over time? What is the structure today? And what is its impact?

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina , Diana Beltekian and Max Roser

This page was first published in 2014 and last revised in April 2024.

On this topic page, you can find data, visualizations, and research on historical and current patterns of international trade, as well as discussions of their origins and effects.

Other research and writing on trade and globalization on Our World in Data:

- Is globalization an engine of economic development?

- Is trade a major driver of income inequality?

Related topics

Economic Growth

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on economic growth.

Economic Inequality

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on economic inequality.

See all our data, visualizations, and writing on migration.

See all interactive charts on Trade and Globalization ↓

Trade has changed the world economy

Trade has grown remarkably over the last century.

One of the most important developments of the last century has been the integration of national economies into a global economic system. This process of integration, often called globalization, has resulted in a remarkable growth in trade between countries.

The chart here shows the growth of world exports over more than the last two centuries. These estimates are in constant prices (i.e. have been adjusted to account for inflation) and are indexed at 1913 values.

The chart shows an extraordinary growth in international trade over the last couple of centuries: Exports today are more than 40 times larger than in 1913.

You can switch to a logarithmic scale under ‘Settings’. This will help you see that, over the long run, growth has roughly followed an exponential path.

The increase in trade has even outpaced economic growth

The chart above shows how much more trade we have today relative to a century ago. But what about trade relative to total economic output?

Over the last couple of centuries the world economy has experienced sustained positive economic growth , so looking at changes in trade relative to GDP offers another interesting perspective.

The next chart plots the value of traded goods relative to GDP (i.e. the value of merchandise trade as a share of global economic output).

Up to 1870, the sum of worldwide exports accounted for less than 10% of global output. Today, the value of exported goods around the world is around 25%. This shows that over the last hundred years, the growth in trade has even outpaced rapid economic growth.

Trade expanded in two waves

The first "wave of globalization" started in the 19th century, the second one after ww2.

The following visualization presents a compilation of available trade estimates, showing the evolution of world exports and imports as a share of global economic output .

This metric (the ratio of total trade, exports plus imports, to global GDP) is known as the “openness index”. The higher the index, the higher the influence of trade transactions on global economic activity. 1

As we can see, until 1800 there was a long period characterized by persistently low international trade – globally the index never exceeded 10% before 1800. This then changed over the course of the 19th century, when technological advances triggered a period of marked growth in world trade – the so-called “first wave of globalization”.

This first wave came to an end with the beginning of World War I, when the decline of liberalism and the rise of nationalism led to a slump in international trade. In the chart we see a large drop in the interwar period.

After World War II trade started growing again. This new – and ongoing – wave of globalization has seen international trade grow faster than ever before. Today the sum of exports and imports across nations amounts to more than 50% of the value of total global output.

Before the first wave of globalization, trade was driven mostly by colonialism

Over the early modern period, transoceanic flows of goods between empires and colonies accounted for an important part of international trade. The following visualizations provide a comparison of intercontinental trade, in per capita terms, for different countries.

As we can see, intercontinental trade was very dynamic, with volumes varying considerably across time and from empire to empire.

Leonor Freire Costa, Nuno Palma, and Jaime Reis, who compiled and published the original data shown here, argue that trade, also in this period, had a substantial positive impact on the economy. 2

The first wave of globalization was marked by the rise and collapse of intra-European trade

The following visualization shows a detailed overview of Western European exports by destination. Figures correspond to export-to-GDP ratios (i.e. the sum of the value of exports from all Western European countries, divided by the total GDP in this region). You can use “Settings” to switch to a relative view and see the proportional contribution of each region to total Western European exports.

This chart shows that growth in Western European trade throughout the 19th century was largely driven by trade within the region: In the period 1830-1900 intra-European exports went from 1% of GDP to 10% of GDP, and this meant that the relative weight of intra-European exports doubled over the period. However, this process of European integration then collapsed sharply in the interwar period.

After the Second World War trade within Europe rebounded, and from the 1990s onwards exceeded the highest levels of the first wave of globalization. In addition, Western Europe then started to increasingly trade with Asia, the Americas, and to a smaller extent Africa and Oceania.

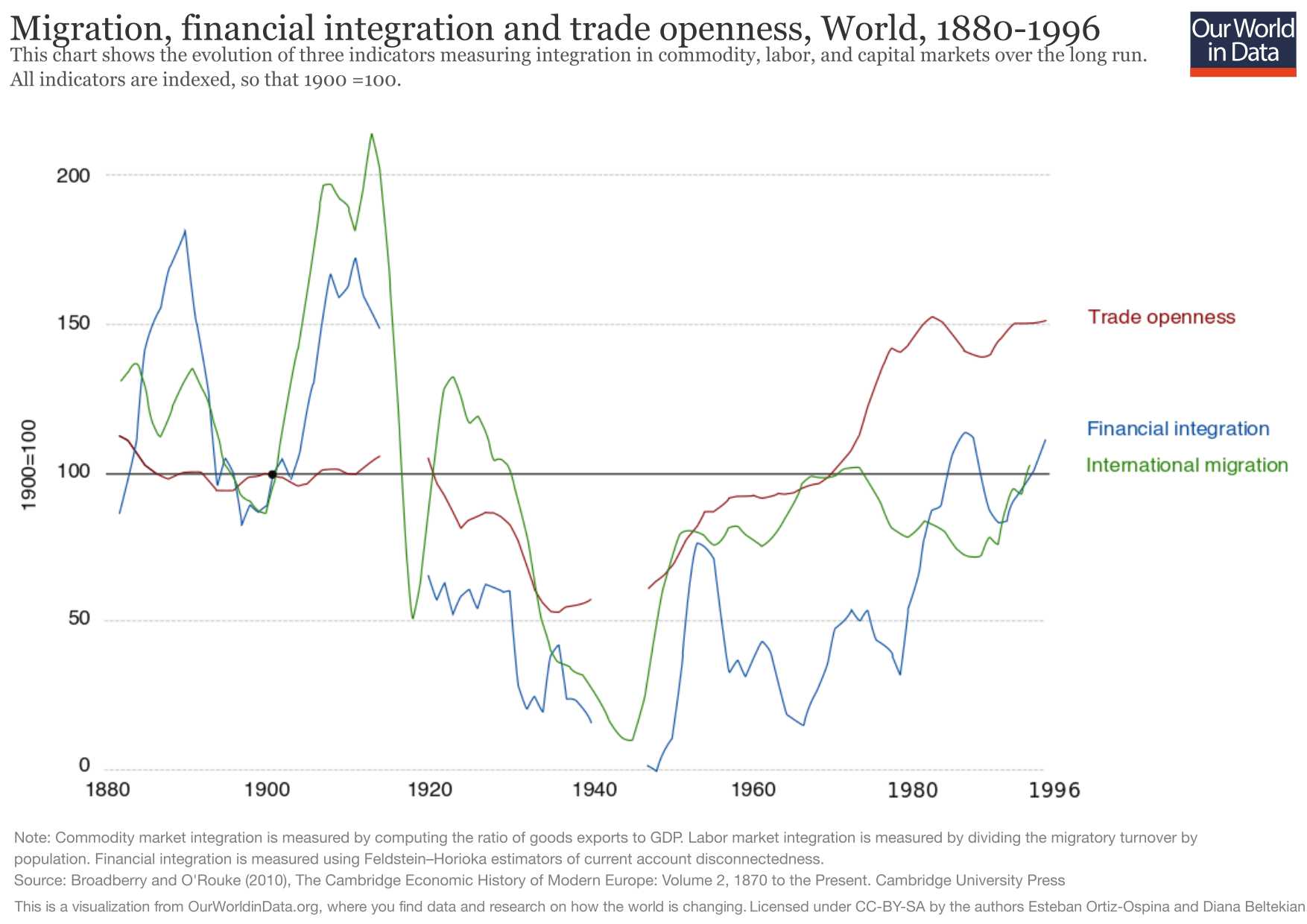

The next graph, using data from Broadberry and O'Rourke (2010) 3 , shows another perspective on the integration of the global economy and plots the evolution of three indicators measuring integration across different markets – specifically goods, labor, and capital markets.

The indicators in this chart are indexed, so they show changes relative to the levels of integration observed in 1900. This gives us another perspective on how quickly global integration collapsed with the two World Wars. 4

The second wave of globalization was enabled by technology

The worldwide expansion of trade after the Second World War was largely possible because of reductions in transaction costs stemming from technological advances, such as the development of commercial civil aviation, the improvement of productivity in the merchant marines, and the democratization of the telephone as the main mode of communication. The visualization shows how, at the global level, costs across these three variables have been going down since 1930.

Reductions in transaction costs impacted not only the volumes of trade but also the types of exchanges that were possible and profitable.

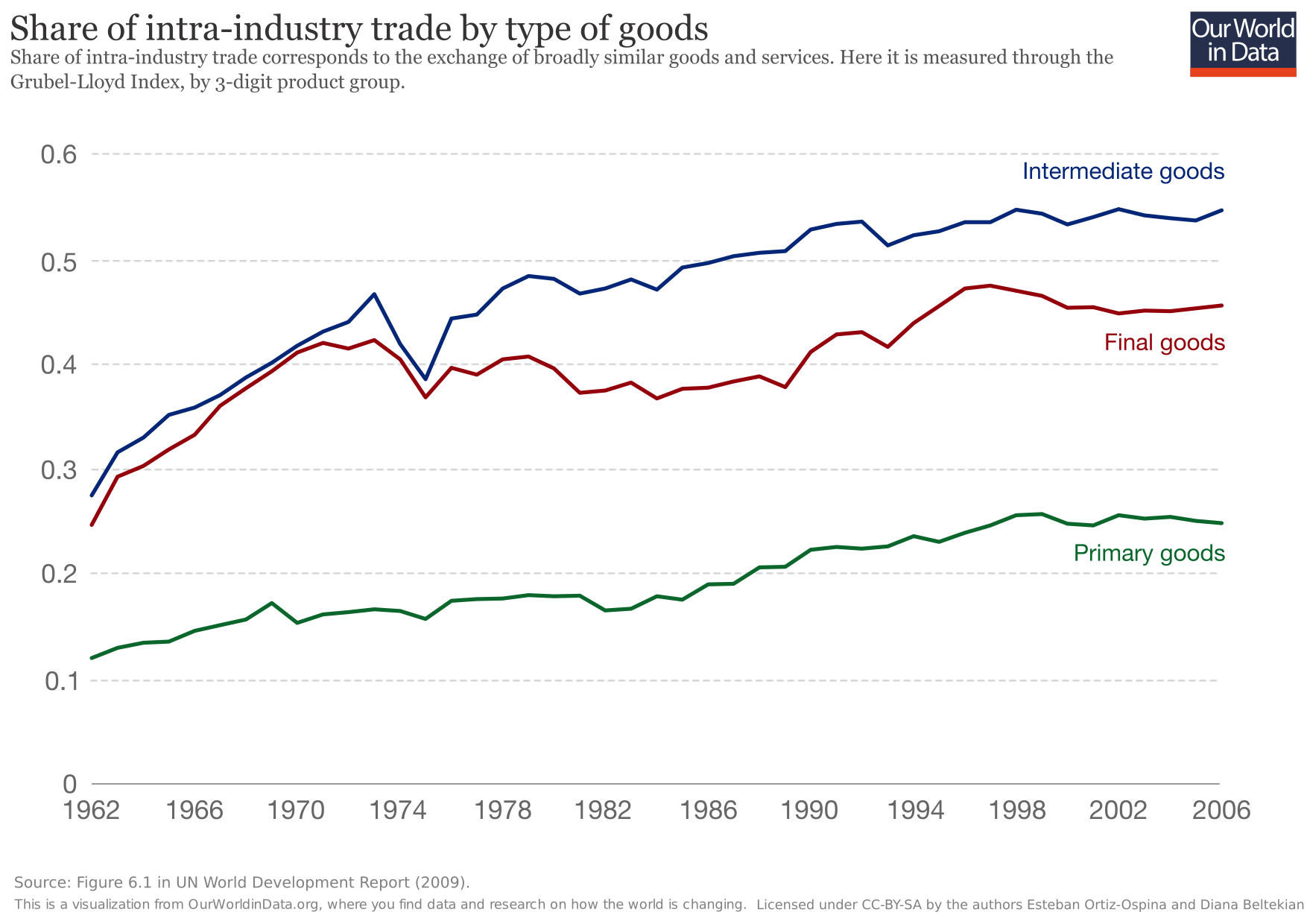

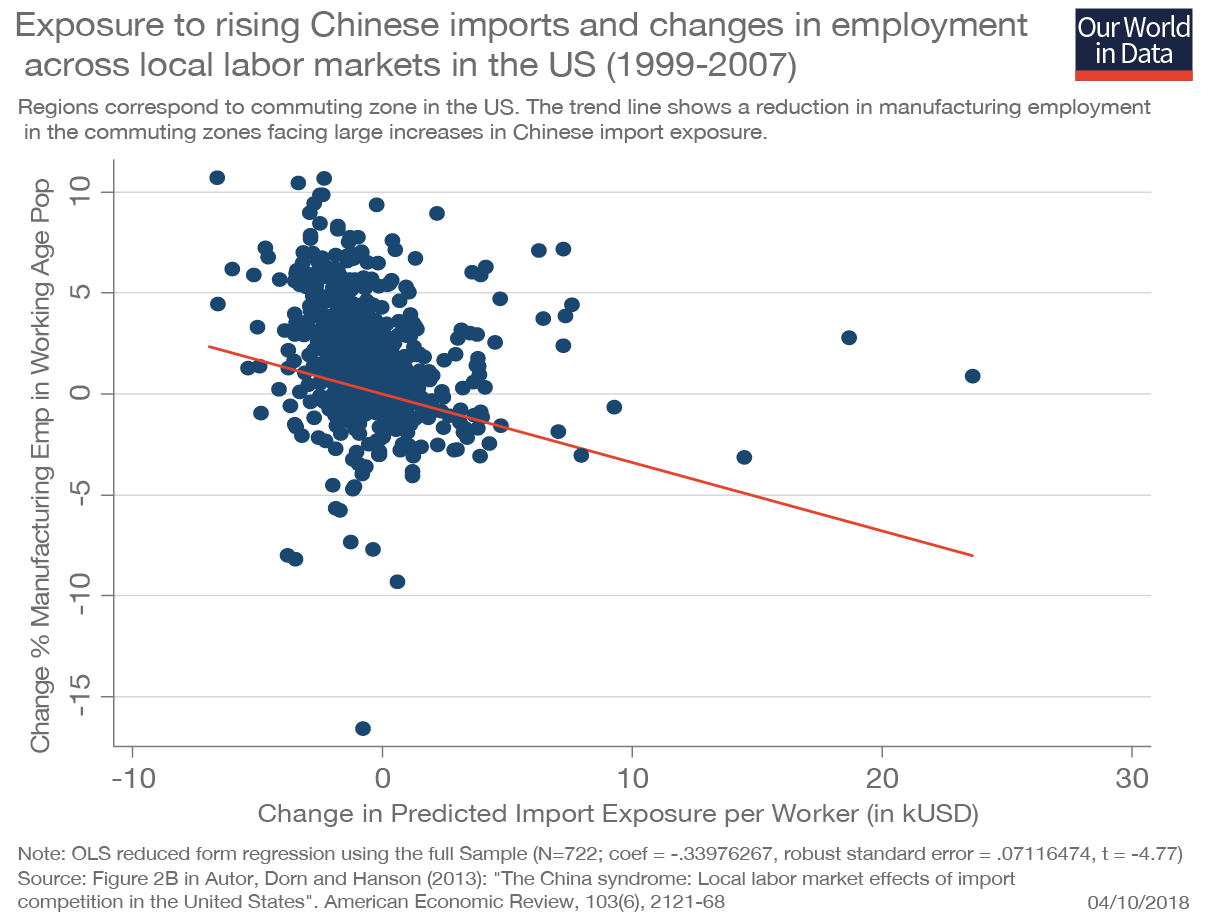

The first wave of globalization was characterized by inter-industry trade. This means that countries exported goods that were very different from what they imported – England exchanged machines for Australian wool and Indian tea. As transaction costs went down, this changed. In the second wave of globalization, we are seeing a rise in intra -industry trade (i.e. the exchange of broadly similar goods and services is becoming more and more common). France, for example, now both imports and exports machines to and from Germany.

The following visualization, from the UN World Development Report (2009) , plots the fraction of total world trade that is accounted for by intra-industry trade, by type of goods. As we can see, intra-industry trade has been going up for primary, intermediate, and final goods.

This pattern of trade is important because the scope for specialization increases if countries are able to exchange intermediate goods (e.g. auto parts) for related final goods (e.g. cars).

Trade and trade partners by country

Above, we examined the broad global trends over the last two centuries. Let's now examine country-level trends over this long and dynamic period.

This chart plots estimates of the value of trade in goods, relative to total economic activity (i.e. export-to-GDP ratios).

These historical estimates obviously come with a large margin of error (in the measurement section below we discuss the data limitations); yet they offer an interesting perspective.

You can edit the countries and regions selected. Each country tells a different story. 6

In the next chart we plot, country by country, the regional breakdown of exports. India is shown by default, but you can edit the countries and regions shown.

When switching to displaying relative values under ‘Settings’, we see the proportional contribution of purchases from each region. For example, we see that more than a third of Indian exports went to Asian countries in recent decades.

This gives us an interesting perspective on the changing nature of trade partnerships. In India, we see the rising importance of trade with Africa—a pattern that we discuss in more detail below .

Trade around the world today

How much do countries trade, trade openness around the world.

The metric trade as a share of GDP gives us an idea of global integration by capturing all incoming and outgoing transactions of a country.