Poetry & Poets

Explore the beauty of poetry – discover the poet within

How To Write A Poetry Research Paper

Introduction

Writing a poetry research paper can be an intimidating task for students. Even for experienced writers, the process of writing a research paper on poetry can be daunting. However, there are a few helpful tips and guidelines that can help make the process easier. Writing a research paper on poetry requires the student to have an analytical understanding of the poet or poet’s work and to utilize multiple sources of evidence in order to make a convincing argument. Before starting the research paper, it is important to properly analyze the poem and to understand the form, structure, and language of the poem.

The process of writing a research paper requires numerous steps, beginning with researching the poet and poem. If a poet is unknown, the research process must be started by learning about their biography, other works, and their impact on society. With online databases, libraries, and archives the research process can move quickly. It is important to carefully document sources for later use when creating bibliographies for the paper. Once the process of researching the poem has been completed, the next step is to analyze the poem itself. It is important for the student to read the poem carefully in order to understand the meaning, as well as its tone, imagery, and metaphors. Furthermore, analyzing other poems by the same poet can help students observe patterns, trends, or elements of a poet’s work.

Outlining and Structure

Outlining the research paper is just as important as analyzing the poem itself. Many students make the mistake of not taking enough time to craft a detailed outline that follows the structure of the paper. An effective outline will make process of writing the research paper more efficient, allowing for ease of transitions between sections of the paper. When writing the paper, it is important to think through the structure of the paper and how to make a strong argument. Support for the argument should be based on concrete evidence, such as literary criticism, literary theory, and close readings of the poem. It is essential to have a clear argument that is consistent throughout the body of the paper.

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper it is also important to cite all sources that are used. The style used for citing sources will depend on the style guide indicated by the professor or the school’s guidelines. Whether using MLA, APA, or Chicago style, it is important to adhere to the style guide indicated in order to have a complete and well-written paper.

Once the research and outlining is complete, the process of drafting a poetry research paper can begin. When constructing the first draft, it is especially useful to re-read the poem and to recall evidence that supports the argument made about the poem. Additionally, it is important to proofread and edit the first draft in order to make the argument more clear and to check for any grammar or spelling errors.

Writing a research paper on poetry does not have to be a difficult task. By taking the time to properly research, analyze, and structure the paper, the process of writing a successful poetry research paper becomes easier. Following these steps— researching the poet, understanding the poem itself, outlining the paper, citing sources, and drafting the paper— will ensure a great and thorough paper is prepared.

Using Imagery and Metaphor

The use of imagery and metaphor is an essential element when writing poetry. Imagery can be used to provide vivid descriptions of scenes and characters, while metaphor can be used to create deeper meanings and analogies. Understanding the use of imagery and metaphor can help to break down the poem and discover hidden meanings. Students researching poetry should pay special attentions to the poetic devices used to further the story or allusions to other works, such as classical mythology. Paying close attention to the language, metaphors, and imagery used by the poet can help to uncover the true meaning of the poem. By breaking down the element of the poem and focusing on individual elements, it is much easier to make valid conclusions about the poem and its author.

Understanding Rhyme and Meter

Rhyme and meter are two of the most important and complex elements of poetry. These two poetic techniques are used to help the poet structure their poem to provide rhythm and flow. Most commonly, rhyme and meter help to provide emphasis to certain words or phrases to give them additional meaning. When analyzing poetry, it is important to pay attention to the written rhyme schemes and meter of the poem. There are various patterns of rhyme, such as couplets, tercets, and quatrains. Meter, usually governed by iambs and trochees, can give the poem an added sense of rhythm to further emphasize certain words, phrases, or thoughts.

Exploring Themes

Themes are the central ideas behind a poem. The themes of a poem can be subtle and can be found in the language and images used. Exploring the poem through a thematic analysis can help to identify the true meaning of the poem and the message that the poet is conveying. When researching a poem, it is important to identify the primary theme of the poem and to look for evidence in the poem that can be used to support the claim. By paying attention to the language of a poem, students can uncover the deeper meanings within the poem and can move past the literal interpretation of the poem.

Analyzing Discourse and Context

In addition to the written aspects of a poem, it is important to consider the historical and social context of the poem. The context of the poem can be used to further understand its deeper meanings and implications. Collingwood’s theory of re-enactment can be used to reconstruct the context of a poem in order to gain a deeper understanding of the poem. When researching a poem, it is important to consider the the time period in which the poem was written, the author’s other works, and the broader literary context of the poem. Examining the discourse used by the poet can help to uncover the true message of the poem and the impact on society at the time.

Finding Inspiration

When researching poetry, it is important for the student to find inspiration in the form of other authors, critics, and theorists. Studying the works of other authors can provide valuable insight into a poem and can inform the student’s own interpretations. In addition to studying critics and theorists, the student should also look to other poets and authors as sources of inspiration. The student can explore the works of similar poets or authors to learn how they use their poetic elements in their work. This can help students to gain insight into the language, imagery, and themes present in the poem being researched.

Minnie Walters

Minnie Walters is a passionate writer and lover of poetry. She has a deep knowledge and appreciation for the work of famous poets such as William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and many more. She hopes you will also fall in love with poetry!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Fordham Library News

The latest from the Fordham University Libraries

A Guide to Researching Poetry

By Jeannie Hoag, Reference and Assessment Librarian

Tips for Researching Poetry

Among many other delightful signs of spring, April brings us National Poetry Month. Springtime during a pandemic is a contradictory mix of delights and shadows –an imperfectly perfect opportunity for poetry.

This is the 25th year we’ve been graced with National Poetry Month . If you regularly recognize National Poetry Month, it might be a welcome reminder of normalcy. And if you’ve never celebrated this month but want to dip your toe into the waters of the poetry pond, you’ve chosen a great time to explore. Below, you will find a few tips to help you get started with poetry research. A proposal: keep it simple, and let subject terms do the hard work for you.

Tip #1: Start Local

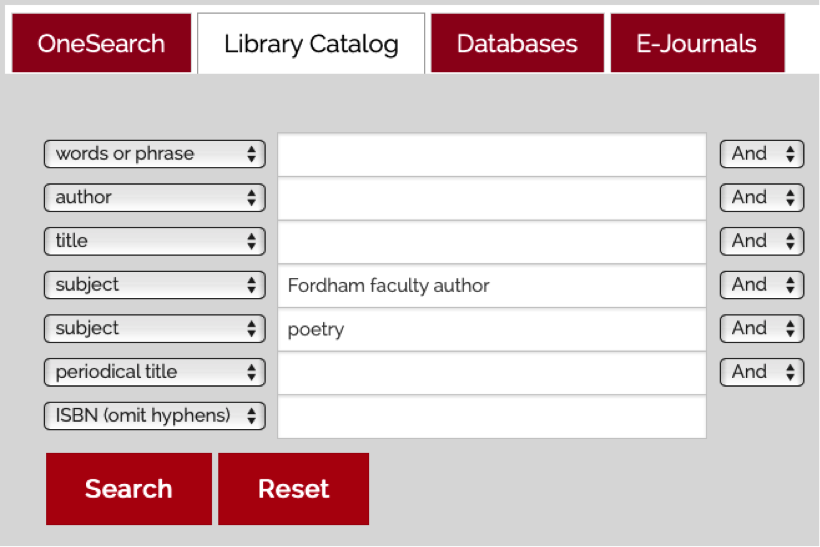

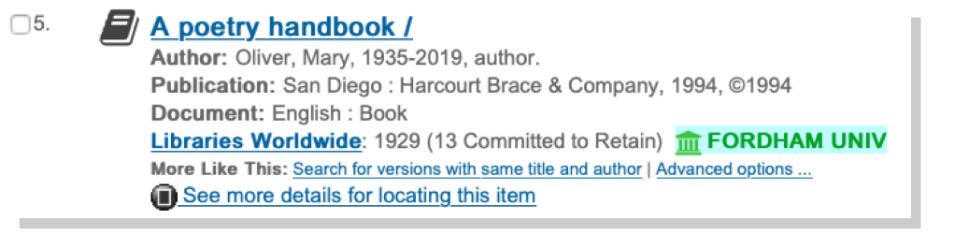

First, let’s look at what’s happening on the local front. The library catalog makes it easy to identify works by Fordham faculty. Add in a few well-chosen limiters, and you can quickly pull together a list of books to dig into.

For example, by using the library catalog’s Advanced Search view, you can search using the subject terms “Fordham faculty author” and “poetry.” You’ll come away with a list of books of poetry, or books about poetry, by our very own faculty members. (This works for other topics, too.)

If you’re interested in exploring beyond Fordham, you can simply use the subject term “poetry” to find all the resources that are poetry-related. With over 35,000 results, that may be a bit overwhelming, so consider using some of these more specific subject terms:

- Narrative poetry

- Prose poems

- Modern poetry

- Jesuit poetry

And for focusing on poetry craft and technique, consider:

- Poetry authorship

- Poetry teaching

- Poetry criticism

If you’re able to visit the Walsh or Quinn libraries, might enjoy browsing by using this list of Library of Congress call numbers for Languages and Literatures . Some of the best discoveries come by way of serendipity. Even easier, pay a visit to the Poetry Room on the 3rd floor of Walsh Library, where you’ll find poetry spanning continents and centuries.

Tip #2: Get Specialized

Do you have a specific poetry need? Maybe a line has been zipping around, unidentified, all week. Or perhaps you’re officiating a wedding, dedicating a building, or tasked with making a public pronouncement that would benefit from a well-chosen poem.

Whatever your scenario, try Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry . This database provides a hearty amount of information, including the full text of some poems, author information, and subject indexing (497 poems about hair, 2 about haggis). It even notes applicable anthologies.

As with all our databases, you can locate Columbia Granger’s via the Databases tab on the library website. The advanced search option gives you maximum control, while the browse option is great for those who are just looking.

Tip #3: Expand Your Horizons

As you can see, the field of poetry is delightfully nuanced. If you’ve exhausted Fordham Libraries’ coverage of your area of interest, look globally to WorldCat .

WorldCat is a powerhouse “world catalog,” and is located on the library website under Resources .

Using the same Library of Congress subject terms you used in your library catalog search, you can see what’s available on your topic at libraries worldwide. For example, using the advanced search option in WorldCat, you can search for other books with the subject of poetry authorship.

In the results, books at Fordham are clearly labeled.

Find something interesting that’s not at Fordham? You can request it through ILLiad, our interlibrary loan service . And if it’s something you think Fordham should have, you can suggest it for purchase .

The Fordham Libraries has many excellent books and great databases for researching poetry. Whether you’re looking for literary criticism, biographies, or individual poems, we’ve got you covered. The Poetry research guide is full of recommended resources. Not finding what you’re looking for? Just ask a librarian. Our chat service is staffed 24/7, and you can also email our library liaisons directly.

More From the Blog

Adelaide Hasse: The GPO’s Founding Mother of the SUDOC Classification System

World Tai Chi & QiGong Day

EH -- Researching Poems: Strategies for Poetry Research

- Find Articles

- Strategies for Poetry Research

Page Overview

This page addresses the research process -- the things that should be done before the actual writing of the paper -- and strategies for engaging in the process. Although this LibGuide focuses on researching poems or poetry, this particular page is more general in scope and is applicable to most lower-division college research assignments.

Before You Begin

Before beginning any research process, first be absolutely sure you know the requirements of the assignment. Things such as

- the date the completed project is due

- the due dates of any intermediate assignments, like turning in a working bibliography or notes

- the length requirement (minimum word count), if any

- the minimum number and types (for example, books or articles from scholarly, peer-reviewed journals) of sources required

These formal requirements are as much a part of the assignment as the paper itself. They form the box into which you must fit your work. Do not take them lightly.

When possible, it is helpful to subdivide the overall research process into phases, a tactic which

- makes the idea of research less intimidating because you are dealing with sections at a time rather than the whole process

- makes the process easier to manage

- gives a sense of accomplishment as you move from one phase to the next

Characteristics of a Well-written Paper

Although there are many details that must be given attention in writing a research paper, there are three major criteria which must be met. A well-written paper is

- Unified: the paper has only one major idea; or, if it seeks to address multiple points, one point is given priority and the others are subordinated to it.

- Coherent: the body of the paper presents its contents in a logical order easy for readers to follow; use of transitional phrases (in addition, because of this, therefore, etc.) between paragraphs and sentences is important.

- Complete: the paper delivers on everything it promises and does not leave questions in the mind of the reader; everything mentioned in the introduction is discussed somewhere in the paper; the conclusion does not introduce new ideas or anything not already addressed in the paper.

Basic Research Strategy

- How to Research From Pellissippi State Community College Libraries: discusses the principal components of a simple search strategy.

- Basic Research Strategies From Nassau Community College: a start-up guide for college level research that supplements the information in the preceding link. Tabs two, three, and four plus the Web Evaluation tab are the most useful for JSU students. As with any LibGuide originating from another campus, care must be taken to recognize the information which is applicable generally from that which applies solely to the Guide's home campus. .

- Information Literacy Tutorial From Nassau Community College: an elaboration on the material covered in the preceding link (also from NCC) which discusses that material in greater depth. The quizzes and surveys may be ignored.

Things to Keep in Mind

Although a research assignment can be daunting, there are things which can make the process less stressful, more manageable, and yield a better result. And they are generally applicable across all types and levels of research.

1. Be aware of the parameters of the assignment: topic selection options, due date, length requirement, source requirements. These form the box into which you must fit your work.

2. Treat the assignment as a series of components or stages rather than one undivided whole.

- devise a schedule for each task in the process: topic selection and refinement (background/overview information), source material from books (JaxCat), source material from journals (databases/Discovery), other sources (internet, interviews, non-print materials); the note-taking, drafting, and editing processes.

- stick to your timetable. Time can be on your side as a researcher, but only if you keep to your schedule and do not delay or put everything off until just before the assignment deadline.

3. Leave enough time between your final draft and the submission date of your work that you can do one final proofread after the paper is no longer "fresh" to you. You may find passages that need additional work because you see that what is on the page and what you meant to write are quite different. Even better, have a friend or classmate read your final draft before you submit it. A fresh pair of eyes sometimes has clearer vision.

4. If at any point in the process you encounter difficulties, consult a librarian. Hunters use guides; fishermen use guides. Explorers use guides. When you are doing research, you are an explorer in the realm of ideas; your librarian is your guide.

A Note on Sources

Research requires engagement with various types of sources.

- Primary sources: the thing itself, such as letters, diaries, documents, a painting, a sculpture; in lower-division literary research, usually a play, poem, or short story.

- Secondary sources: information about the primary source, such as books, essays, journal articles, although images and other media also might be included. Companions, dictionaries, and encyclopedias are secondary sources.

- Tertiary sources: things such as bibliographies, indexes, or electronic databases (minus the full text) which serve as guides to point researchers toward secondary sources. A full text database would be a combination of a secondary and tertiary source; some books have a bibliography of additional sources in the back.

Accessing sources requires going through various "information portals," each designed to principally support a certain type of content. Houston Cole Library provides four principal information portals:

- JaxCat online catalog: books, although other items such as journals, newspapers, DVDs, and musical scores also may be searched for.

- Electronic databases: journal articles, newspaper stories, interviews, reviews (and a few books; JaxCat still should be the "go-to" portal for books). JaxCat indexes records for the complete item: the book, journal, newspaper, CD but has no records for parts of the complete item: the article in the journal, the editorial in the newspaper, the song off the CD. Databases contain records for these things.

- Discovery Search: mostly journal articles, but also (some) books and (some) random internet pages. Discovery combines elements of the other three information portals and is especially useful for searches where one is researching a new or obscure topic about which little is likely to be written, or does not know where the desired information may be concentrated. Discovery is the only portal which permits simul-searching across databases provided by multiple vendors.

- Internet (Bing, Dogpile, DuckDuckGo, Google, etc.): primarily webpages, especially for businesses (.com), government divisions at all levels (.gov), or organizations (.org). as well as pages for primary source-type documents such as lesson plans and public-domain books. While book content (Google Books) and journal articles (Google Scholar) are accessible, these are not the strengths of the internet and more successful searches for this type of content can be performed through JaxCat and the databases.

NOTE: There is no predetermined hierarchy among these information portals as regards which one should be used most or gone to first. These considerations depend on the task at hand and will vary from assignment o assignment.

The link below provides further information on the different source types.

- Research Methods From Truckee Meadows Community College: a guide to basic research. The tab "What Type of Source?" presents an overview of the various types of information sources, identifying the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- << Previous: Find Books

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2024 7:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/litresearchpoems

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing About Poetry

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Writing about poetry can be one of the most demanding tasks that many students face in a literature class. Poetry, by its very nature, makes demands on a writer who attempts to analyze it that other forms of literature do not. So how can you write a clear, confident, well-supported essay about poetry? This handout offers answers to some common questions about writing about poetry.

What's the Point?

In order to write effectively about poetry, one needs a clear idea of what the point of writing about poetry is. When you are assigned an analytical essay about a poem in an English class, the goal of the assignment is usually to argue a specific thesis about the poem, using your analysis of specific elements in the poem and how those elements relate to each other to support your thesis.

So why would your teacher give you such an assignment? What are the benefits of learning to write analytic essays about poetry? Several important reasons suggest themselves:

- To help you learn to make a text-based argument. That is, to help you to defend ideas based on a text that is available to you and other readers. This sharpens your reasoning skills by forcing you to formulate an interpretation of something someone else has written and to support that interpretation by providing logically valid reasons why someone else who has read the poem should agree with your argument. This isn't a skill that is just important in academics, by the way. Lawyers, politicians, and journalists often find that they need to make use of similar skills.

- To help you to understand what you are reading more fully. Nothing causes a person to make an extra effort to understand difficult material like the task of writing about it. Also, writing has a way of helping you to see things that you may have otherwise missed simply by causing you to think about how to frame your own analysis.

- To help you enjoy poetry more! This may sound unlikely, but one of the real pleasures of poetry is the opportunity to wrestle with the text and co-create meaning with the author. When you put together a well-constructed analysis of the poem, you are not only showing that you understand what is there, you are also contributing to an ongoing conversation about the poem. If your reading is convincing enough, everyone who has read your essay will get a little more out of the poem because of your analysis.

What Should I Know about Writing about Poetry?

Most importantly, you should realize that a paper that you write about a poem or poems is an argument. Make sure that you have something specific that you want to say about the poem that you are discussing. This specific argument that you want to make about the poem will be your thesis. You will support this thesis by drawing examples and evidence from the poem itself. In order to make a credible argument about the poem, you will want to analyze how the poem works—what genre the poem fits into, what its themes are, and what poetic techniques and figures of speech are used.

What Can I Write About?

Theme: One place to start when writing about poetry is to look at any significant themes that emerge in the poetry. Does the poetry deal with themes related to love, death, war, or peace? What other themes show up in the poem? Are there particular historical events that are mentioned in the poem? What are the most important concepts that are addressed in the poem?

Genre: What kind of poem are you looking at? Is it an epic (a long poem on a heroic subject)? Is it a sonnet (a brief poem, usually consisting of fourteen lines)? Is it an ode? A satire? An elegy? A lyric? Does it fit into a specific literary movement such as Modernism, Romanticism, Neoclassicism, or Renaissance poetry? This is another place where you may need to do some research in an introductory poetry text or encyclopedia to find out what distinguishes specific genres and movements.

Versification: Look closely at the poem's rhyme and meter. Is there an identifiable rhyme scheme? Is there a set number of syllables in each line? The most common meter for poetry in English is iambic pentameter, which has five feet of two syllables each (thus the name "pentameter") in each of which the strongly stressed syllable follows the unstressed syllable. You can learn more about rhyme and meter by consulting our handout on sound and meter in poetry or the introduction to a standard textbook for poetry such as the Norton Anthology of Poetry . Also relevant to this category of concerns are techniques such as caesura (a pause in the middle of a line) and enjambment (continuing a grammatical sentence or clause from one line to the next). Is there anything that you can tell about the poem from the choices that the author has made in this area? For more information about important literary terms, see our handout on the subject.

Figures of speech: Are there literary devices being used that affect how you read the poem? Here are some examples of commonly discussed figures of speech:

- metaphor: comparison between two unlike things

- simile: comparison between two unlike things using "like" or "as"

- metonymy: one thing stands for something else that is closely related to it (For example, using the phrase "the crown" to refer to the king would be an example of metonymy.)

- synecdoche: a part stands in for a whole (For example, in the phrase "all hands on deck," "hands" stands in for the people in the ship's crew.)

- personification: a non-human thing is endowed with human characteristics

- litotes: a double negative is used for poetic effect (example: not unlike, not displeased)

- irony: a difference between the surface meaning of the words and the implications that may be drawn from them

Cultural Context: How does the poem you are looking at relate to the historical context in which it was written? For example, what's the cultural significance of Walt Whitman's famous elegy for Lincoln "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed" in light of post-Civil War cultural trends in the U.S.A? How does John Donne's devotional poetry relate to the contentious religious climate in seventeenth-century England? These questions may take you out of the literature section of your library altogether and involve finding out about philosophy, history, religion, economics, music, or the visual arts.

What Style Should I Use?

It is useful to follow some standard conventions when writing about poetry. First, when you analyze a poem, it is best to use present tense rather than past tense for your verbs. Second, you will want to make use of numerous quotations from the poem and explain their meaning and their significance to your argument. After all, if you do not quote the poem itself when you are making an argument about it, you damage your credibility. If your teacher asks for outside criticism of the poem as well, you should also cite points made by other critics that are relevant to your argument. A third point to remember is that there are various citation formats for citing both the material you get from the poems themselves and the information you get from other critical sources. The most common citation format for writing about poetry is the Modern Language Association (MLA) format .

How to Research Poetry

To locate biographical material or criticism in books, perform an alphabetical SUBJECT SEARCH in the Library Catalog ( catalog.nypl.org ) typing in the last name of the poet followed by the first name.

The search yielded six different subject headings. It is important to look deeper into each one of these headings, especially the one that indicates "Criticism and Interpretation." In this example, there are nine books of criticism and interpretation of Sexton's poetry.

- Once you find a book of on the shelf, check books nearby with similar call numbers for other sources.

- Pay special attention to the bibliographies and suggestions for further reading. These lists will contain titles of other books and journal articles that are related to the subject.

- Biographies do more than tell the life stories of a poet: they often contain criticism of specific poems that is accessed through the index in the back of the book.

REFERENCE BOOKS - Multi-volume and self-indexing sources

**The information in the following Magill's books is also available at the Mid-Manhattan Library from the online database Magill On Literature Plus .

- Magill's Critical Survey of Poetry-English Language Series** This 8-volume set presents an essay on each poet included. Each essay contains essential information that includes: Principal poetry, Other Literary forms, Achievements, Biography, Analysis, and Bibliography. An excellent introduction to poetry criticism. The index at the end of the eighth volume is very useful.

- Magill's Critical Survey of Poetry-Foreign Language Series ** Arranged similarly to the English Language Series, this series contains extensive essays on poets who wrote in a language other than English. The essays include the same information found for poets in the English Language Series. Volume 5 indexes the entire set and contains longer essays that discuss an entire country's poetry. Examples of some essays include: "Hungarian Poetry," "Ancient Greek Poetry", and "Third World Poetry."

- Magill's Masterplots II-Poetry Series ** This multi-volume set focuses on analyzing specific famous poems. Use the index in Volume 9 to locate the poet, then the poem you are researching. Each signed essay has three sections: "The Poem," "Forms and Devices" and "Themes and Meanings."

- Explicator Cyclopedia (in 2 volumes) Ref 820.9 E; Kept at Librarians Desk. References to brief but important criticism of specific poems arranged alphabetically by poet. Each entry originally appeared in the journal The Explicator. The contributor's name and date of publication is given.

- Poetry Criticism This very popular reference series contains "excerpts from criticism of the works of the most significant and widely studied poets of world literature." Ask at the librarian's desk to see the "Annual Cumulative Title Index" to determine the exact volumes and pages that mention the specific poem or poet you are researching. In addition, you can use the Gale Literary Index from the Literature Resource Center database to get an index to articles in a wide variety of literary criticism sets.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES - books that direct you to other books and journal articles that discuss the poet you are researching.

The following helpful bibliographies refer you to the exact pages a given poem is discussed in periodicals or books.

- Kuntz, Joseph M, ed. Poetry Explication: a Checklist of Interpretation since 1925 of British and American Poems Past and Present

- Martinez, Nancy C., ed., Guide to British Poetry Explication (in three volumes)

- Coleman, Arthur, ed., Epic and Romance Criticism

- Anderson, Emily Ann, ed., English Poetry , 1900-1950

- Aubrey, Bryan, ed., English Romantic Poetry. (Magill Bibliographies)

- Leo, John R., ed., Guide to American Poetry Explication, Vol 2, Modern and Contemporary

REFERENCE BOOKS - Complete in One Volume

Contemporary Poets REF 821.914 Kept at librarian's desk Concise, signed, articles about poets that include personal information, a list of publications, and a critical examination of the complete body of works with a look at a few specific poems.

The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics REF 808.103. Kept at librarian's desk. If you are seeking definitions of poetic terms, poetic movements, and an essay on the poetry of a given country, this is an excellent place to start. Each entry, though often brief, is exhaustive, and is signed, often with a bibliography.

Encyclopedia of American Poetry: The Twentieth Century Ready REF 811.5 This is a good starting source for researching American poets and poetic movements of the 20th century. A concise biography and a useful list of suggestions for further reading follow a signed essay discussing the poets and their major achievements. In depth analysis of one or more specific poems is often included.

ONLINE POETRY CRITICISM

The New York Public Library subscribes to many databases that contain either citations to, or in many cases the full text of, critical articles from literary journals and books. Some of these databases are available from home with a valid New York Public Library card at www.nypl.org/databases . The Literature Resource Center and Magill On Literature Plus are two excellent databases that provide many full-text articles of criticism and biography. Other databases such as JSTOR and the MLA Bibliography are more advanced, but link to information from the best literary journals and chapters of books.

For more help on using these and other online databases ask the literature librarian and consult the guide entitled ONLINE LITERARY CRITICISM: A Guide to Research available at the library.

- Spartanburg Community College Library

- SCC Research Guides

ENG 102 - Poetry Research

- 3. Narrow Your Topic

As you start to work on your thesis and supporting examples, you'll want to brainstorm keywords that might help you find secondary sources. You may decide to adjust your topic or thesis as you search for sources. This is a natural part of the research process. See below for some help on brainstorming keywords.

As you think about what concepts you want to write about, think about what particular words might be found in a good article about that topic. Consider the following when searching databases and e-books:

- Enter the name of the poem with the word "and" and the concept you are looking for E xample: "The Raven and Death"

- Keywords work best by trial-and-error

- Never do only one search

Revenge --- Vengeance

Death --- Mortality --- Murder

Gender --- Feminism --- Sex

Remember to also use "Search Within Results" option to search further into your results.

- Use "Ctrl F" to search for specific words within a particular article.

- And remember to ask a librarian if you need assistance coming up with keywords or looking for sources.

- << Previous: 2. Explore Your Topic

- Next: 4. Find Sources >>

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Explore Your Topic

- 4. Find Sources

- 5. Cite Your Sources

- 6. Evaluate Your Sources

- 7. Write Your Paper

- Literary Criticism Guide

Questions? Ask a Librarian

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 12:19 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sccsc.edu/Poetry

Giles Campus | 864.592.4764 | Toll Free 866.542.2779 | Contact Us

Copyright © 2024 Spartanburg Community College. All rights reserved.

Info for Library Staff | Guide Search

Return to SCC Website

Poetry Is an Act of Hope

Through verse, we can perhaps come closest to capturing events that exist beyond our capacity to describe.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Poetry is the art form that most expands my sense of what language can do. Today, so much daily English feels flat or distracted—politicians speak in clichés; friends are distracted in conversation by the tempting dinging of smartphones; TV dialogue and the sentences in books are frequently inelegant. This isn’t a disaster: Clichés endure because they convey ideas efficiently; not all small talk can be scintillating; a bad sentence here or there in a novel won’t necessarily condemn the whole work.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic ’s Books section:

- When your every decision feels torturous

- “Noon”: a poem by Li-Young Lee

- A prominent free-speech group is fighting for its life.

- The complicated ethics of rare-book collecting

Poetry is different, however. We expect more from it. Not a single word should be misused, not a single syllable misplaced—and, as a result, studying language within the poetic form can be particularly rewarding. In March and April of this year, two of America’s great poetry critics, Helen Vendler and Marjorie Perloff, died. In reading Adam Kirsch’s tribute to both, I was struck by how different their respective approaches to language were. Vendler was a “traditionalist,” per Kirsch; she liked poets who “communicated intimate thoughts and emotions in beautiful, complex language.” She was a famous close reader, carefully picking over poems to draw out every sense of meaning. For Vendler, Kirsch writes, poetry made language “more meaningful.”

Perloff wasn’t as interested in communicating meaning. Her favorite avant-garde poets used words in surprising and odd ways. As Kirsch writes, “At a time when television and advertising were making words smooth and empty, she argued that poets had a moral duty to resist by using language disruptively, forcing readers to sit up and pay attention.”

I’d reckon that neither Perloff nor Vendler relished lines that were smooth and empty, even though their preferred artists and attitudes toward reading might have differed. Ben Lerner has said that poetry represents a desire to “do something with words that we can’t actually do.” In that sense, poems are a declaration of hope in language: Even if we can’t pull off something magnificent, we can at least try.

Through poetry, we can perhaps come closest to capturing the events that feel so extreme as to exist beyond our capacity to describe them. In the February 8 issue of The New York Review of Books , Ann Lauterbach published a poem called “ War Zone ,” dedicated to Paul Auster, another literary great who died recently. The poem depicts not scenes of violence and gore but the hollow wordlessness many of us feel in the face of war or suffering—then it uses images of silence, blankness, and absence to fight against that unspeakability. The last line, which I won’t spoil here, points to this paradox: Words may not be able to capture everything—especially the worst things—but they can, and must, try.

When Poetry Could Define a Life

By Adam Kirsch

The close passing of the poetry critics Marjorie Perloff and Helen Vendler is a moment to recognize the end of an era.

Read the full article.

What to Read

The Taste of Country Cooking , by Edna Lewis

Lewis’s exemplary Southern cookbook is interspersed with essays on growing up in a farming community in Virginia; many of the recipes in the book unspool from these memories. Lewis, who worked as a chef in New York City as well as in North and South Carolina, writes with great sensual and emotional detail about growing up close to the land. Of springtime, she writes, “The quiet beauty in rebirth there was so enchanting it caused us to stand still in silence and absorb all we heard and saw. The palest liverwort, the elegant pink lady’s-slipper displayed against the velvety green path of moss leading endlessly through the woods.” Her book was ahead of its time in so many ways: It is a farm-to-table manifesto, a food memoir published decades before Ruth Reichl popularized the form, and an early, refined version of the cookbook-with-essays we’re now seeing from contemporary authors such as Eric Kim and Reem Assil. The recipes—ham biscuits, new cabbage with scallions, potted stuffed squab—are as alluring as the prose. — Marian Bull

From our list: eight cookbooks worth reading cover to cover

Out Next Week

📚 First Love , by Lilly Dancyger

📚 América del Norte , by Nicolás Medina Mora

📚 The Lady Waiting , by Magdalena Zyzak

Your Weekend Read

The Diminishing Returns of Having Good Taste

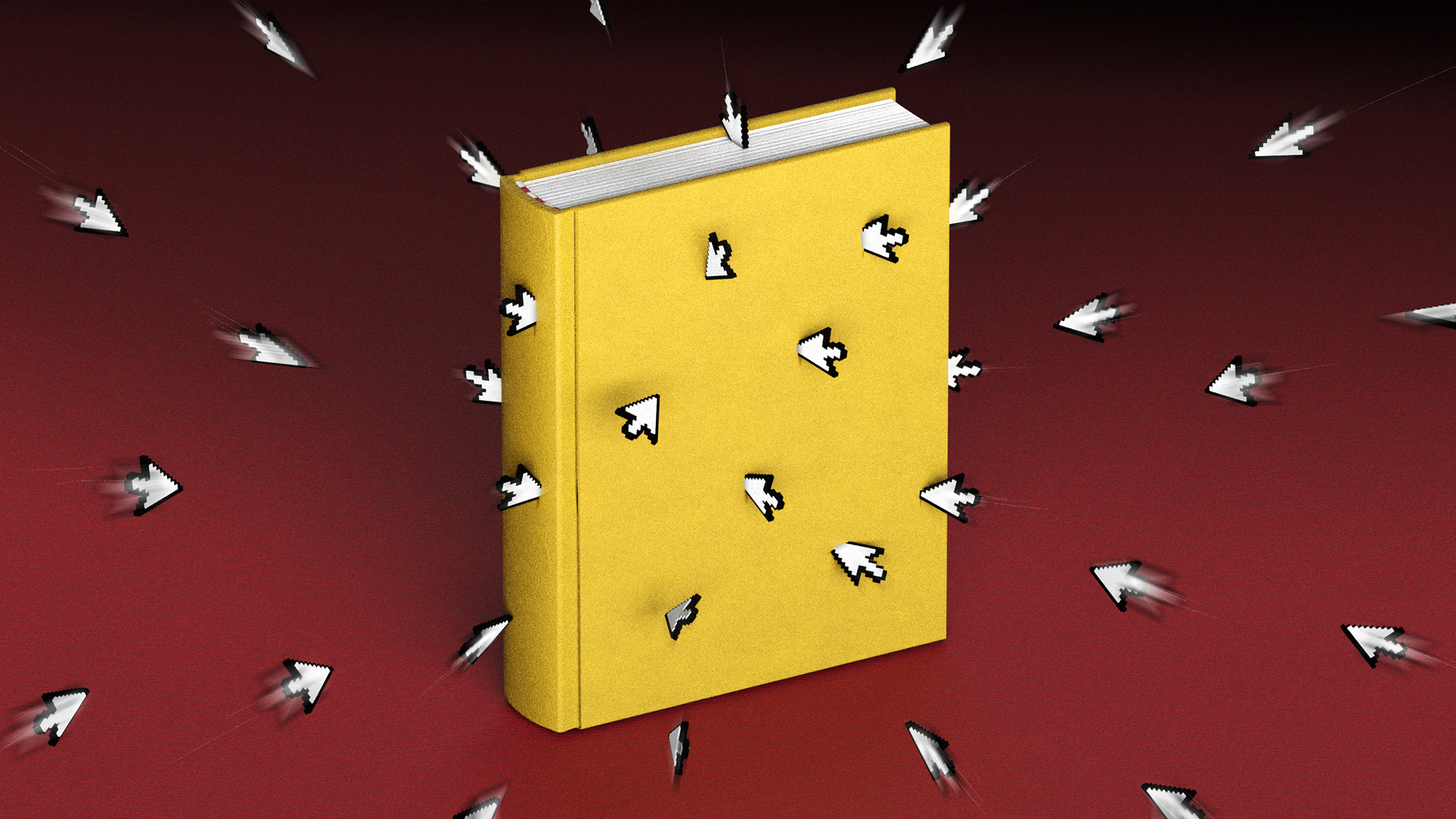

By W. David Marx

There are obvious, concrete advantages to a world with information equality, such as expanding global access to health and educational materials—with a stable internet connection, anyone can learn basic computer programming from online tutorials and lectures on YouTube. Finding the optimal place to eat at any moment is certainly easier than it used to be. And, in the case of Google, to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” even serves as the company’s mission. The most commonly cited disadvantage to this extraordinary societal change, and for good reason, is that disinformation and misinformation can use the same easy pathways to spread unchecked. But after three decades of living with the internet, it’s clear that there are other, more subtle losses that come with instant access to knowledge, and we’ve yet to wrestle—interpersonally and culturally—with the implications.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic .

Explore all of our newsletters .

Advertisement

Supported by

In a Poem, Just Who Is ‘the Speaker,’ Anyway?

Critics and readers love the term, but it can be awfully slippery to pin down. That’s what makes it so fun to try.

- Share full article

By Elisa Gabbert

Elisa Gabbert’s collections of poetry and essays include, most recently, “Normal Distance” and the forthcoming “Any Person Is the Only Self.” Her On Poetry columns appear four times a year.

The pages of “A Little White Shadow,” by Mary Ruefle, house a lyric “I” — the ghost voice that emerges so often from what we call a poem. Yet the I belonged first to another book, a Christian text of the same name published in 1890, by Emily Malbone Morgan.

Ruefle “erased” most words of Morgan’s text with white paint, leaving what look like lines of verse on the yellowed pages: “my brain/grows weary/just thinking how to make/thought.” (My virgules are approximate — should I read all white gaps as line breaks, even if the words are in the same line of prose? Are larger gaps meant to form stanzas?)

On another page, we read (can I say Ruefle writes ?): “I was brought in contact/with the phenomenon/peculiar to/’A/shadow.’” It would be difficult to read Ruefle’s book without attributing that I to the author, to Ruefle, one way or another, although the book’s I existed long before she did.

This method of finding an I out there, already typed, to identify with, seems to me not much different from typing an I . An I on the page is abstract, symbolic, and not the same I as in speech, which in itself is not the same I as the I in the mind.

When an old friend asked me recently if I didn’t find the idea of “the speaker” to be somewhat underexamined, I was surprised by the force of the YES that rose up in me. I too had been following the critical convention of referring to whatever point of view a poem seems to generate as “the speaker” — a useful convention in that it (supposedly) prevents us from ascribing the views of the poem to its author. But in that moment I realized I feel a little fraudulent doing so. Why is that?

Perhaps because I never think of a “speaker” when writing a poem. I don’t posit some paper-doll self that I can make say things. It’s more true to say that the poem always gives my own I, my mind’s I, the magic ability to say things I wouldn’t in speech or in prose.

It’s not just that the poem, like a play or a novel, is fictive — that these genres offer plausible deniability, though they do. It’s also that formal constraints have the power to give us new thoughts. Sometimes, in order to make a line sound good, to fit the shape of the poem, I’m forced to cut a word or choose a different word, and what I thought I wanted to say gets more interesting. The poem has more surprising thoughts than I do.

“The speaker,” as a concept, makes two strong suggestions. One is that the voice of a poem is a kind of persona. In fact, when I looked for an entry on the subject in our New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (a tome if there ever was one, at 1,383 pages), I found only: “Speaker: See PERSONA.” This latter term is an “ancient distinction,” writes the scholar Fabian Gudas, between poems in the poet’s “own voice” and those in which “characters” are speaking.

But, as the entry goes on to note, 20th-century critics have questioned whether we can ever look at a poem as “the direct utterance of its author.” While persona seems too strong to apply to some first-person lyrics, the speaker implies all lyrics wear a veil of persona, at least, if not a full mask.

The second implication is that the voice is a voice — that a poem has spokenness , even just lying there silent on the page.

The question here, the one I think my friend was asking, is this: Does our use of “the speaker” as shorthand — for responsible readership, respectful acknowledgment of distance between poet and text — sort of let us off the hook? Does it give us an excuse to think less deeply than we might about degrees of persona and spokenness in any given poem?

Take Louise Glück’s “The Wild Iris,” “a book in which flowers speak,” as Glück herself described it. One flower speaks this, in “Trillium”: “I woke up ignorant in a forest;/only a moment ago, I didn’t know my voice/if one were given me/would be so full of grief.” (I find a note that I’ve stuck on this page, at some point: The flowers give permission to express .)

“Flowers don’t have voices,” James Longenbach writes, in his essay “The Spokenness of Poetry” — “but it takes a flower to remind us that poems don’t really have voices either.”

They’re more like scores for voices, maybe. A score isn’t music — it’s paper, not sound — and, as Jos Charles writes in an essay in “Personal Best: Makers on Their Poems That Matter Most,” “the written poem is often mistaken for the poem itself.” A poem, like a piece of music, she writes, “is neither its score nor any one performance,” but what is repeatable across all performances. Any reader reading a poem performs it — we channel the ghost voice.

There are poems that have almost no spokenness — such as Aram Saroyan’s “minimal poems,” which might consist of a single nonword on the page (“lighght,” most famously, but see also “morni,ng” or “Blod”). Or consider Paul Violi’s “Index,” whose first line is “Hudney, Sutej IX, X, XI, 7, 9, 25, 58, 60, 61, 64.” Is anyone speaking the page numbers?

And there are poems that have almost no persona, as in the microgenre whose speaker is a poetry instructor (see “Introduction to Poetry,” by Billy Collins).

Yet I’m not interested only in edge cases. There are so many subtle gradations of “speaker” in the middle, so much room for permission. A speaker may seem threatening, as in June Jordan’s “Poem About My Rights”: “from now on my resistance … may very well cost you your life.” A speaker may seem dishonest — Tove Ditlevsen’s first published poem was called “To My Dead Child,” addressing a stillborn infant who had in fact never existed.

Auden would say it’s hard not to “tell lies” in a poem, where “all facts and all beliefs cease to be true or false and become interesting possibilities.” So, we might say, the “speaker” is the vessel for the full range of lies that the poet is willing to tell.

“Poetry is not for personal confessions,” George Seferis wrote in a journal; “it expresses another personality that belongs to everyone.” This suggests poetry comes from some underlying self. If, by invoking “the speaker,” I avoid a conflation of the I and its author, I may also crowd the page with more figures than I need: a speaker and an author, both outside the poem. I wonder sometimes if there’s anyone there, when I’m reading. Does the speaker speak the poem? Or does the poem just speak?

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

As book bans have surged in Florida, the novelist Lauren Groff has opened a bookstore called The Lynx, a hub for author readings, book club gatherings and workshops , where banned titles are prominently displayed.

Eighteen books were recognized as winners or finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, in the categories of history, memoir, poetry, general nonfiction, fiction and biography, which had two winners. Here’s a full list of the winners .

Montreal is a city as appealing for its beauty as for its shadows. Here, t he novelist Mona Awad recommends books that are “both dreamy and uncompromising.”

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Poetry and the Meaning of Care

- 1 Associate Editor, JAMA

- Poetry and Medicine Even Joy Fred H. Reinhart, BFA, MBA JAMA

Health care is becoming more and more distanced. Clinicians must overcome not just mountains of data, burdensome electronic health records, and ever-increasing numbers of machines that separate us from patients, but more recently also navigate telemedicine and AI-driven chatbots. Physician-writer Dr Abraham Verghese and others have lamented that consequently we rely less on the physical exam 1 and the connection it fosters with patients, as echocardiography and CT scans impersonally scrutinize them instead. So, a poem like “Even Joy” 2 is a welcome corrective, a poignant reminder of the value of simple human touch in medicine. The speaker of the poem, whose relationship to the cradled newborn is never disclosed—is the poet her parent, a hospital volunteer, a clinician?—is certainly a healer in a fundamental sense. The infant described almost dismissively in the first line as born “with half a brain,” who won’t live more than a few days, is dignified by the speaker’s tender attention, becoming in this inviolate gaze a whole person. “There are her gifts: still-pink skin,/a perfect nose” the voice intones, using poetry’s own gifts of list-making and close observation to transcend the incubator’s plastic barrier. Touch, the speaker demonstrates, is a way to know “aliveness minute by minute,/to consecrate a singular being.” Poetry, then, has as much value here as the imaging study that diagnoses anencephaly, and by the comfort it provides, perhaps is even more “miraculous” than any technology that can only soullessly peer inside us.

Read More About

Campo R. Poetry and the Meaning of Care. JAMA. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.5422

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

COMMENTS

The core of this collection of essays arises out of an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project, 'The Uses of Poetry' (2013-14), led by Kate Rumbold, Footnote 3 that brought together evidence and expertise from a team of eminent and emerging scholars on the uses and values of poetry at different stages of life in order to ...

Feeling the pen scribble over the page, Physically out of control of the paper, Exposing the inside of a poet's heart. This leads me to discuss how poetry can help unravel concepts that might ...

Abstract. In this study, situated in the borderland between traditional and artistic methodologies, we innovatively represent our research findings in both prose and poetry. This is an act of exploration and resistance to hegemonic assumptions about legitimate research writing. A content analysis of young adult literature featuring trafficked ...

Abstract- "When teaching poetry to students, we must first examine our own apprehensions, preconceived notions, and. perceived abilities as poets. " Parr & Campbell (2006). In fact, the ...

Discussion has occurred around what constitutes quality research poetry, with some direction on how a researcher, who is a novice poet, might go about writing good enough research poetry. In an effort to increase the existing conversation, the authors review research poetry literature and ideas from art poets on how to read, write, and revise poetry.

9. Exploring Themes. 10. Analyzing Discourse and Context. 11. Finding Inspiration. Writing a poetry research paper can be an intimidating task for students. Even for experienced writers, the process of writing a research paper on poetry can be daunting. However, there are a few helpful tips and guidelines that can help make the process easier.

Gary Snapper. For forty years or more, much of the discourse about poetry in education has constructed poetry teaching and learning as an especially difficult professional problem to be solved. The problem has been analysed in many different ways: as a product of inadequate teacher subject knowledge and pedagogical fear; as an inherent problem ...

Here is the answer. The author is a practitioner doing research and reflecting about his ministry, and own practice as a writer, to understand the impact of poetry on readers, with a view to improve his work. He has developed his own theories: - about poetry as a means of research, and - poetry as a form of therapy.

that poetry still can and must have a rhetorical function and a social impact. All three writers believe that great poetry transcends what Donald Revell calls "wiles and strate-gies," and all share an impulse toward experimentation, the ongoing desire to "make it new." Real Sofistikashun: Essays on Poetry and Craft collects fourteen of Tony ...

Tips for Researching Poetry. Among many other delightful signs of spring, April brings us National Poetry Month. Springtime during a pandemic is a contradictory mix of delights and shadows-an imperfectly perfect opportunity for poetry.. This is the 25th year we've been graced with National Poetry Month.If you regularly recognize National Poetry Month, it might be a welcome reminder of ...

For Howe, researching and writing are complementary, mutually affecting acts. Howe's poet-researcher is a scout, a rover, a trespasser unsettling the wilderness of American literary history. Her poems and essays continually enact that anticipatory moment before discovery, of making connections, before anything is ever fixed into ideas.

Essays on Poetic Theory. This section collects famous historical essays about poetry that have greatly influenced the art. Written by poets and critics from a wide range of historical, cultural, and aesthetic perspectives, the essays address the purpose of poetry, the possibilities of language, and the role of the poet in the world.

Abstract. This paper presents a stylistic analysis of two poems of well-known poets of. the English l iterature, namely; E .E. Cummings and the Irish noble laureate Seamus. Heaney. The research er ...

It provides information on poetry as a literary genre, important elements of poetry, including things to look for in reading a poem, and other information. ... Although there are many details that must be given attention in writing a research paper, there are three major criteria which must be met. A well-written paper is. Unified: the paper ...

It is useful to follow some standard conventions when writing about poetry. First, when you analyze a poem, it is best to use present tense rather than past tense for your verbs. Second, you will want to make use of numerous quotations from the poem and explain their meaning and their significance to your argument.

English 102 - Poetry Research. This guide is designed to help you complete an English 102 research paper about a poem. Follow the steps below in order - each step builds on the one before it, guiding you through the research project. We offer research advice/tips, as well as recommended sources, citation help, etc. Next: 1.

Poetry matters because it is a central example of the use human beings make of words to explore and understand. Like other forms of writing we value, it lends shape and meaning to our experiences and helps ... The core of this collection of essays arises out of an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project, 'The Uses of Poetry ...

ENG 102 - Poetry Research. This guide is designed to help you complete an English 102 research paper about a poem. 4. Find Sources. Once you have narrowed your topic and thought about keywords, try searching the databases below for potential sources you can use to support your thesis. If your keywords aren't working ask a librarian for help!

This research paper delves into the significance of nature in Romantic poetry, focusing on the works of five major poets: Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats. ... Central to Romantic literature and particularly evident in its poetry was the emphasis on nature—not merely as a scenic backdrop against which human drama played out ...

Main Paragraphs. Now, we come to the main body of the essay, the quality of which will ultimately determine the strength of our essay. This section should comprise of 4-5 paragraphs, and each of these should analyze an aspect of the poem and then link the effect that aspect creates to the poem's themes or message.

The essays include the same information found for poets in the English Language Series. Volume 5 indexes the entire set and contains longer essays that discuss an entire country's poetry. Examples of some essays include: "Hungarian Poetry," "Ancient Greek Poetry", and "Third World Poetry." Magill's Masterplots II-Poetry Series**

ENG 102 - Poetry Research. This guide is designed to help you complete an English 102 research paper about a poem. 3. Narrow Your Topic. Once you've done some initial exploration of the poem, it's time to narrow your focus to some concrete aspects you want to focus in on. Choose the aspects of the poem that you think will be most helpful to ...

Step-by-step Instructions for Writing the Poetry Research Paper. It can be challenging to write a research paper about poetry if you are given the assignment. But if you take the appropriate method, you can divide it into manageable steps. The following is a step-by-step tutorial on how to write an effective poetry research paper: Step 1 ...

Declan Ryan on his father's construction job, tenderness between boxers, and the inevitable tragic end. Monica Rico on cooking, grunt work, and the heat at General Motors. Poems, readings, poetry news and the entire 110-year archive of POETRY magazine.

Illustration by The Atlantic. May 3, 2024. This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors' weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here. Poetry is the art form that most expands ...

Elisa Gabbert's collections of poetry and essays include, most recently, "Normal Distance" and the forthcoming "Any Person Is the Only Self." Her On Poetry columns appear four times a ...

Poetry, then, has as much value here as the imaging study that diagnoses anencephaly, and by the comfort it provides, perhaps is even more "miraculous" than any technology that can only soullessly peer inside us. ... Duke University Press, and Arte Público Press from the sale of books of original poetry and essays. References. 1.