Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

103 Procrastination Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Procrastination is something that many of us struggle with at some point in our lives. Whether it's putting off studying for an exam, starting a new project, or even just doing the laundry, procrastination can be a major roadblock to productivity. If you're struggling to come up with a topic for an essay on procrastination, we've got you covered. Here are 103 procrastination essay topic ideas and examples to help get you started:

The psychology behind procrastination: why do we put things off?

The impact of procrastination on academic performance

Procrastination in the workplace: how it affects productivity

The relationship between procrastination and mental health

Strategies for overcoming procrastination

The role of technology in encouraging procrastination

Procrastination as a form of self-sabotage

Procrastination and perfectionism: are they related?

The link between procrastination and procrastination

Procrastination and decision-making: how putting things off can lead to poor choices

The role of procrastination in creating stress and anxiety

Procrastination and time management: how better planning can help

Procrastination and creativity: is there a connection?

Procrastination and self-discipline: how to build better habits

The impact of procrastination on relationships

Procrastination and goal-setting: how putting things off can derail your dreams

The connection between procrastination and fear of failure

Procrastination and procrastination addiction: when putting things off becomes a habit

Procrastination and procrastination bias: why we underestimate how long tasks will take

The impact of procrastination on physical health

Procrastination and procrastination guilt: the cycle of putting things off and feeling bad about it

The connection between procrastination and procrastination reward: why we feel good when we procrastinate

Procrastination and procrastination procrastination: how putting things off can lead to even more procrastination

The role of procrastination in decision fatigue

Procrastination and self-awareness: recognizing when you're avoiding tasks

The impact of procrastination on creativity

Procrastination and procrastination procrastination: why we put things off even when we know it's not helpful

The connection between procrastination and procrastination bias: why we underestimate how long tasks will take

Hopefully, these essay topic ideas and examples have sparked some inspiration for your own writing on procrastination. Whether you choose to explore the psychological roots of procrastination, the impact it has on various aspects of our lives, or strategies for overcoming it, there's plenty to explore on this fascinating topic. Good luck with your essay!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 25 June 2024

Temporal discounting predicts procrastination in the real world

- Pei Yuan Zhang 1 &

- Wei Ji Ma 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 14642 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1023 Accesses

16 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

People procrastinate, but why? One long-standing hypothesis is that temporal discounting drives procrastination: in a task with a distant future reward, the discounted future reward fails to provide sufficient motivation to initiate work early. However, empirical evidence for this hypothesis has been lacking. Here, we used a long-term real-world task and a novel measure of procrastination to examine the association between temporal discounting and real-world procrastination. To measure procrastination, we critically measured the entire time course of the work progress instead of a single endpoint, such as task completion day. This approach allowed us to compute a fine-grained metric of procrastination. We found a positive correlation between individuals’ degree of future reward discounting and their level of procrastination, suggesting that temporal discounting is a cognitive mechanism underlying procrastination. We found no evidence of a correlation when we, instead, measured procrastination by task completion day or by survey. This association between temporal discounting and procrastination offers empirical support for targeted interventions that could mitigate procrastination, such as modifying incentive systems to reduce the delay to a reward and lowering discount rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hybrid working from home improves retention without damaging performance

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Using games to understand the mind

Introduction.

In today’s world, achieving long-term goals, such as writing an article or developing complex software, demands sustained effort spanning days or months. These endeavors are crucial for both personal success and societal productivity, yet they often collide with the challenge of procrastination. Procrastination is prevalent; it chronically affects approximately 20% of the adult population 1 and up to 70% of undergraduate students 2 . For instance, people delay filing their taxes until the last minute 3 . Researchers postpone until the last minute registering for academic conferences 4 and submitting abstracts and papers 5 . College students commonly put off starting self-paced quizzes and find themselves rushing to complete them by the end of the semester 6 , 7 , 8 . The consequences of procrastination are profound, impacting individuals’ achievements and well-being. Procrastination results in lower salaries, shorter employment durations, a higher likelihood of unemployment 9 , and monetary loss 3 . Beyond these tangible effects, procrastinators frequently suffer from mental health challenges, including depression and anxiety, compounded by diminished motivation and low self-esteem 6 , 10 , 11 . Due to its high prevalence and high impact, procrastination is a problem of great societal importance.

The question arises: why do people procrastinate? Suppose you are a student who has to submit an assignment by a deadline. Initially, the utility of working on the assignment might be low because the deadline is far away, making work less appealing than alternative activities such as socializing. As a result, the student might delay working on the assignment until the utility of work exceeds the utility of socializing, which occurs as the deadline approaches. In line with this example, researchers in psychology and economics have, in different forms, hypothesized that temporal discounting is a mechanism underlying procrastination 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 . When faced with a task in its initial stages, where the eventual reward is distant, people temporarily discount the value of that future reward. As a consequence, the temporarily discounted future reward fails to provide sufficient motivation for people to start working until the deadline looms near.

This hypothesis predicts a positive correlation between the degree to which individuals discount future rewards and the extent of their procrastination. As far as we know, only three studies have attempted to test for this correlation 17 , 18 , 19 . Le Bouc and Pessiglione 17 measured procrastination behavior in a survey completion task and found no evidence of a correlation. Sutcliffe et al. 18 used a questionnaire to measure self-reported procrastination tendency and found no evidence of a correlation. Reuben et al. 19 found a positive correlation in two real-world tasks that offered enhanced rewards as incentives for early completion. However, such incentives could be a confound because the actual correlation might be between temporal discounting and achievement motivation 20 , 21 . Indeed, the authors did not find a correlation when early completion incentives were removed in a third task. Two other studies 22 , 23 appear to examine the relationship between temporal discounting and procrastination. They used a hyperbolic function to model the distribution of task completion time across individuals. The same function is commonly used to estimate temporal discount rates by modeling how future reward is discounted over time. However, these studies did not measure temporal discount rates, even though the same hyperbolic function was used.

In the present work, we used a novel measure of procrastination in a novel task to examine the association between temporal discounting and real-world procrastination behavior. It is common in the literature to use a single endpoint—task completion time—as a measure of procrastination 4 , 5 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 . However, individuals who complete a task at the same time can exhibit very different temporal patterns of work progress 28 , 29 , 30 . Some people maintain steady progress from beginning to end (steady working), whereas others make very little progress at the start and rush to complete their work on the very last day (rushing in the end). In order to better distinguish between such cases, we instead used a new metric to measure procrastination—Mean Unit Completion Day—that takes into account the entire time course of work progress.

We looked for a real-world task that satisfied three criteria. First, to rule out the potential confound in Reuben et al. 19 , no incentives should be given for early completion. Second, the task should measure the entire time course of work progress. This, in turn, requires that the task (a) has an unambiguous definition of a unit of work, (b) the completion time of each unit of work is measured, and (c) involves multiple units of work to establish a time course of work progress. Real-world tasks such as writing or taking an academic course often lack clearly defined units of work and are, therefore, not good candidates. Finally, an individual’s work progress in the task should not be affected by others.

A real-world task that satisfied these three criteria was the research participation requirement in the Introduction to Psychology course at New York University. To receive course credit, all enrolled students were required to participate in research studies for a total of 7 h before the end of the semester; the semester lasted a total of 109 days. This task was self-paced, granting students the autonomy to decide when to participate. All three criteria were met in this task. First, since course credit was independent of the time at which the research requirement was completed, no incentives were given for early completion. Second, a unit of work was clearly defined as 0.5 h because research participation opportunities involved a time commitment of 0.5, 1, 1.5, or 2 h. The vast majority (91.2%) of participation opportunities took 0.5 h or 1 h. The date of each research participation was documented in the New York University Sona System and was accessible to the system administrator. Students needed to participate multiple times to fulfill the 7-h requirement. All students participated at least six times, with a median of 10 times. Last, research participation opportunities were plentiful: an average of 15 h per student. Thus, there was no need for students to compete for these opportunities, and each student’s work progress could reasonably be assumed to be independent of that of others. In contrast, if research participation opportunities are limited, whether a student can participate in a study on a certain day depends on whether other students have already taken that opportunity. In this case, a student’s work progress will be dependent on others due to the need to compete for scarce resources.

To estimate the degree of reward discounting, two weeks after the semester ended, we invited all students who had been enrolled in the course to participate in our online study that included a delay discounting task. Participants were asked to indicate their monetary preferences between smaller but sooner rewards and larger but delayed rewards (Fig. 1 A). We used a widely adopted choice set designed to capture a broad range of discount rates 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . The delays in the choice set ranged from 1 to 180 days, comparable to the 109-day research participation task. Moreover, this task was designed to be incentive-compatible, in contrast to the hypothetical nature of rewards in the previous studies 17 , 19 .

The secondary objective of our study was to examine the relationship between risk attitude and behavioral procrastination. By postponing the research participation until the end of the semester, students face an increased risk of not being able to complete the research participation requirement, particularly when considering other competing obligations near the end of the semester, such as final exams. Consequently, procrastination in the research participation task can be viewed as a risk-seeking behavior. A prior study 38 found no evidence of a correlation between the risk attitude measured by the Domain-Specific Risk-Taking (DOSPERT) scale 39 and self-reported procrastination tendency measured by the Lay Procrastination Scale 40 . In this real-world task, we examined the relationship between people’s risk attitude and procrastination behavior. To estimate participants’risk attitude, we included three measures in our online study: the incentive-compatible risky-choice task (Fig. 1 B), which assessed risk attitude primarily within the financial domain 41 , 42 ; the DOSPERT scale, which assessed risk attitude across five domains (ethical, health/safety, recreational, financial, and social), and a set of custom-designed questions that assessed risk attitudes specifically toward postponing research participation in our real-world task (see “ Methods ”).

Tasks. ( A ) Online delay discounting task. In each trial, participants were first presented with two options: a smaller immediate reward today and a larger reward with a delay of several days, and then they indicated their preference by choosing one. At the end of the task, their choice of one randomly selected trial will determine the payment amount and the day of delivery. ( B ) Online risky choice task. In each trial, participants were first presented with two options: receiving $5 for sure and participating in a lottery where they had a chance to win a larger amount with a certain probability, otherwise receiving $0, and then they indicated their preference by choosing one. At the end of the task, the choice of one randomly selected trial will determine the payment. If participants chose the sure bet, they would receive $5. However, if they chose the lottery, they would play it by randomly drawing a chip from 100 chips. As the task was conducted online, we gave participants a visual aid of the chip-drawing process by displaying 100 chips and instructing them to click on a chip to simulate the random draw. After clicking, the color of the chip will be revealed, and the payment will be based on the result of the lottery.

Participants

Participant inclusion was determined as follows. First, to ensure that our measures of procrastination would not be confounded by the total number of work units completed, we selected the participants who met their 7-h requirement and did not continue to do more research sessions beyond the requirement. This resulted in a total of 93 participants. Second, we applied pre-registered exclusion criteria to the delay discounting task. We excluded 9 participants who either failed two or more of the five attention check questions or consistently chose one option. Finally, we conducted a quality control procedure to ensure that participants were not responding randomly (see “ Methods ”). No additional participants were excluded based on this procedure. This left us with a final sample of 84 participants to test the relationship between temporal discounting and procrastination and the convergent validity of our measurement of procrastination (53 female, 28 male, two non-binary, one unknown; \(19.4 \pm 1.4\) years old). To test the relationship between risk attitude and procrastination, we applied similar exclusion criteria and quality control to the risky-choice task (see “ Methods ”), leaving us with a sample of 91 participants (56 female, 31 male, three non-binary, one unknown; \(19.3 \pm 1.8\) years old).

Characterizing individual variability in procrastination

In the research participation task, we found that the time course of work progress differed greatly between individuals, ranging from participants who started and finished early to those who waited until the last two weeks of the 109-day period (Fig. 2 A). The cumulative progress curves across all the participants clearly show this high individual variability (Fig. 2 B).

There are many ways of summarizing a time course of work progress, some of which have been used in previous papers. Perhaps the most obvious summary statistic is task completion time 17 , 19 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 . In our task, the distribution of task completion day is wide, ranging from 25 to 103 days ( \(M=77.5\) , \(SD=17.2\) ) (Fig. 2 C). Another metric is the amount of work (in our task, the number of hours of research participation) completed in the last third of the semester 6 ( \(M=1.7\) , \(SD=2.0\) ) (Supplementary Fig. S1 A). Furthermore, one could use task starting day 25 , 27 , 43 , 44 . In our task, however, students were asked by the instructor to complete the first research participation in the first two weeks. This separate deadline makes the task starting day somewhat contaminated as a measure of procrastination in the overall research participation task. Nevertheless, we show the distribution of task starting day in Supplementary Fig. S1 B.

Procrastination in the real world. ( A ) Examples of time courses of work progress, with blue triangles marking the Mean Unit Completion Day (MUCD). Top: a low procrastinator who started on the first day and finished early. Middle: an intermediate procrastinator who worked steadily throughout the semester. Bottom: a high procrastinator who rushed to complete the task in the last two weeks of the semester. ( B ) Time courses of cumulative work progress for all the participants, with the three examples from ( A ) highlighted. ( C ) Histogram of task completion day. ( D ) Histogram of MUCD.

The above metrics take into account only a single point or partial segment of the time course of work progress. Next, we turn to metrics that consider the entire time course of work progress. We introduce a novel metric, Mean Unit Completion Day (MUCD), as the average completion day of all work units, with each work unit defined in this task as 0.5 h of research participation (see the formula in the Supplement). MUCD had a wide distribution, ranging from 19.1 to 100.9 ( \(M = 49.6\) , \(SD= 18.2\) ), further demonstrating the high level of individual variability in procrastination (Fig. 2 D).

We assessed the convergent validity of MUCD by testing whether MUCD in the research participation task is associated with self-reported procrastination in general academic situations. We measured participants’general academic procrastination tendencies with the widely used Procrastination Assessment Scale for Students (PASS) 6 . Participants were asked to report the frequency with which they procrastinated on tasks such as writing term papers, studying for exams, and four other academic scenarios. Our findings revealed a moderate positive correlation between MUCD and PASS score (Pearson \(r=0.42\) , \(p<0.001\) ), which provides support for the convergent validity of our measure.

Two other metrics are closely related to MUCD. The first is the day of the halfway point of the work 7 , which is the median of the time course of work progress ( \(M = 50.5\) , \(SD= 22.4\) ) (Supplementary Fig. S1 C). The second is the area under the cumulative progress curve 30 ; however, we prove here that this metric is mathematically equivalent to MUCD (see proof in the Supplement).

Besides MUCD, the other metrics were also correlated with the PASS score, suggesting the convergent validity of these measures (task completion day: \(r=0.31\) , \(p=0.005\) ; hours in the last third of the semester: \(r=0.41\) , \(p<0.001\) ; task starting day: \(r=0.36\) , \(p<0.001\) ; day of the halfway point: \(r=0.42\) , \(p<0.001\) ;). All metrics considered were correlated with each other (see Supplementary Table S1 ). All metrics were preregistered, except for task starting day (because of the potential confound of a different deadline) and area under the cumulative progress curve (because of the mathematical equivalence).

Discount rate correlates with behavioral procrastination quantified by MUCD but not task completion day or survey-based measure

Turning to our main question, we examined the correlation between temporal discounting and procrastination. We estimated individual temporal discount rates through the incentive-compatible delay discounting task. We fit a hyperbolic choice model to the choice data of each participant. The discount curves were well characterized by hyperbolic functions (goodness of fit: \(M=0.73\) , \(SD=0.14\) ). We found high variability (Fig. 3 A): the natural log-transformed discount rate ranged from \(-7.87\) (equivalent to a 1.14% discount of reward value after 30 days) to \(-1.39\) (an 88.2% discount of reward value after 30 days). We found a positive correlation between the discount rate and MUCD ( \(r=0.28\) , \(p=0.009\) ) (Fig. 3 B). In addition, after controlling for age and gender, the discount rate was still positively associated with MUCD ( \(\beta =3.6\) , \(SE=1.4\) , \(t(78)=2.53\) , \(p=0.013\) ).

Procrastination correlates with discount rate but not risk attitude. ( A ) Histogram of the natural log-transformed discount rate estimated from the delay discounting task. ( B ) Correlation between MUCD and the natural log-transformed discount rate. ( C ) Histogram of the natural log-transformed risk attitude parameter estimated from the risky-choice task by fitting a power utility model. ( D ) Correlation between MUCD and the natural log-transformed risk attitude estimated from risky-choice task.

We found that (a) day of the halfway point and (b) hours in the last third semester both correlated with the discount rate ( \(r=0.28\) , \(p=0.009\) ; \(r=0.24\) , \(p=0.030\) , respectively), but metric (c) task completion day or (d) task starting day did not ( \(r=0.21\) , \(p=0.061\) ; \(r=0.18\) , \(p=0.098\) , respectively). These results held true after we controlled for age and gender (day of the halfway point: \(\beta =4.3\) , \(SE=1.7\) , \(t(78)=2.52\) , \(p=0.014\) ; hours in the last third semester: \(\beta =0.33\) , \(SE=0.16\) , \(t(78)=2.04\) , \(p=0.044\) ; task completion day: \(\beta =2.4\) , \(SE=1.3\) , \(t(78)=1.80\) , \(p=0.077\) ; task starting day: \(\beta =2.8\) , \(SE=1.8\) , \(t(78)=1.57\) , \(p=0.12\) ). One interpretation of these findings is that measures based on the time course of work progress have greater statistical power than measures based on an endpoint.

We found no correlation between the discount rate and the PASS score ( \(r=0.21\) , \(p=0.056\) ; after we controlled for age and gender: \(\beta =0.088\) , \(SE=0.053\) , \(t(78)=1.65\) , \(p=0.10\) ), highlighting the advantage of behavioral measures of procrastination over survey-based measures.

As an exploratory analysis, we tested if impulsivity, self-control, or perfectionism mediate the correlation between temporal discounting and procrastination. Details are provided in the Supplement.

No evidence of a correlation between risk attitude and behavioral procrastination

To estimate participants’risk attitude, we employed three approaches: the incentive-compatible risky-choice task (Fig. 1 B), the Domain-Specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale 39 , and a set of custom-designed questions that assessed risk attitudes specifically toward postponing research participation in this research participation task: The first question measured participants’perception of the risk associated with not being able to fulfill the research participation requirement by postponing it until the end of the semester, while the last two measured the level of aversion to that risk (see “ Methods ”).

We fitted a power utility model to the individual choice data from the risky-choice task. We found high variability in the risk attitude parameter (Fig. 3 C): the natural log-transformed risk attitude ranged from −1.29 to 0.22. We found no evidence of a correlation between risk attitude and behavioral procrastination in this research participation task characterized by MUCD (Fig. 3 D), day of the halfway point, hours in the last third semester and task completion day ( \(r=0.034\) , \(p=0.75\) ; \(r=0.10\) , \(p=0.35\) ; \(r=0.068\) , \(p=0.52\) ; \(r=-0.064\) , \(p=0.55\) , respectively).

Similarly, we did not find a significant correlation between procrastination and risk attitude measured by the DOSPERT scale across five domains (correlation between MUCD and the mean DOSPERT score: \(r=-0.12\) , \(p=0.25\) ). Specifically, we did not find a correlation between MUCD and risk-taking in the ethical domain ( \(r=-0.081\) , \(p=1.0\) ), in the financial domain ( \(r=0.13\) , \(p=0.83\) ), in the health/safety domain ( \(r=0.012\) \(p=1.0\) ), in the recreational domain ( \(r=-0.16\) , \(p=0.60\) ), or in the social domain ( \(r=-0.022\) , \(p=1.0\) ) (corrected using the Holm-Bonferroni method). Additionally, we did not find a correlation between procrastination and risk perception across five domains measured by the DOSPERT-Risk Perception subscale (correlation between MUCD and risk perception in the ethical domain: \(r=0.011\) , \(p=1.0\) , in the financial domain: \(r=-0.24\) , \(p=0.11\) , in the health/safety domain: \(r=-0.065\) , \(p=1.0\) , in the recreational domain: \(r=-0.035\) , \(p=1.0\) , or in the social domain: \(r=0.025\) , \(p=1.0\) . (corrected using the Holm-Bonferroni method))

Next, we analyzed the questions custom-designed to measure risk attitudes specifically toward postponing research participation. In terms of risk perception (the first question), participants strongly agreed that postponing research participation until the end of the semester increased the risk of not being able to fulfill the requirement (ratings ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7); \(Median = 7\) ; \(Mean = 6.2\) ; \(SD = 1.2\) ). However, we did not find evidence of a correlation between risk perception and procrastination characterized by MUCD, day of the halfway point, hours in the last third semester, or task completion day ( \(r=-0.16\) , \(p=0.14\) ; \(r=-0.14\) , \(p=0.18\) ; \(r=-0.19\) , \(p=0.07\) ; \(r=-0.12\) , \(p=0.27\) , respectively). The results were qualitatively the same for risk attitude (average score across the second and third questions): Participants reported a high level of aversion to the risk of not fulfilling the requirement due to postponing the research participation ( \(Median = 5\) ; \(Mean = 4.8\) ; \(SD = 1.3\) ). However, we did not find evidence of a correlation between risk attitude and procrastination characterized by MUCD, day of the halfway point, hours in the last third semester, or task completion day ( \(r=-0.094\) , \(p=0.37\) ; \(r=-0.13\) , \(p=0.21\) ; \(r=-0.015\) , \(p=0.89\) ; \(r=-0.090\) , \(p=0.40\) , respectively).

Self-reports of procrastination behavior

At the end of our online study, participants answered custom-designed questions about their views on procrastination in the research participation task. For example, they were asked how satisfied they were with how they allocated their time over the semester to fulfill the requirement, their attribution of procrastination, and their top-rated reasons for procrastination (see the Supplement for results). Here, we highlight one result: participants were aware of their own level of procrastination in research participation. Participants were asked to rate their procrastination level from not at all (1) to an extreme extent (5) in fulfilling the research participation requirement. We found that the rating of their own procrastination level in research participation positively correlates with their behavioral level of procrastination characterized by MUCD ( \(r=0.68\) , \(p<0.001\) ). This suggests that participants were aware of their own level of procrastination in the task.

We have presented evidence for an association between reward discounting and procrastination behavior in a long-term real-world task. This suggests that temporal discounting is a potential cognitive mechanism underlying procrastination.

Why did prior studies 17 , 18 , 19 fail to find a correlation between temporal discounting and procrastination? One reason might be that the choice sets they used might not have allowed for estimating the discount rate with the same precision as ours. Another reason might be that their delay discounting task was not incentive-compatible. Finally, their measurement of procrastination might not be as precise as ours. Sutcliffe et al. 18 did not employ a behavioral measure of procrastination; instead, they used a questionnaire. When we applied a similar questionnaire method, no evidence of a correlation was found. The other two studies 17 , 19 measured behavioral procrastination but limited their metrics to the task completion day, as they did not measure the entire time course of work progress. By contrast, we measured the entire time course of work progress and computed fine-grained metrics of procrastination, such as MUCD. This approach might provide greater statistical power than simply using the task completion day as a metric, which, when we applied it, also resulted in no evidence of a correlation. Alternatively, it is possible that stronger and weaker discounters truly do not differ in task completion day but only in how they allocate their time before completion. Future work will need to distinguish these two possibilities.

The observed association between temporal discounting and procrastination suggests two types of interventions to reduce procrastination: one is changing the incentive system, and another is reducing procrastination via lowering discount rates. First, regarding the incentive system, one might reduce procrastination by decreasing the delay in receiving a reward. While previous work has shown that adding immediate rewards to the original incentive environment enhances persistence 45 , 46 and reduces procrastination 47 , it remains unclear whether these effects are due to the increased reward magnitude or to a change in reward timing. Future research should disentangle these two factors and test the effect of decreasing the delay to a reward.

Second, procrastination can be reduced by lowering discount rates. The most promising ways to lower discount rates are episodic future thinking and mindfulness-based training/acceptance-based training 48 , 49 . Mindfulness-based training has been shown to be effective in reducing procrastination 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , but no studies have tested the effect of episodic future thinking on procrastination. One study showed a negative association between episodic future thinking and procrastination 54 . However, the effectiveness of episodic future thinking as an intervention remains to be studied. Future studies should test this intervention using a randomized control trial. Furthermore, future studies could test whether a reduced discount rate mediates the effectiveness of reducing procrastination through episodic future thinking or mindfulness-based training. In addition, the effects of these interventions could vary among individuals with different discount rates (e.g., healthy controls versus clinical populations 55 ). For example, people with ADHD might be more sensitive to interventions that reduce procrastination by lowering discount rates 56 .

Limitations of our work include the use of a WEIRD 57 sample of NYU undergraduates and the use of a non-academic task. Future work should generalize to more diverse global samples and non-academic tasks. Moreover, it is possible that students frame the outcome of the research participation task as avoiding losses (“if I don’t fulfill the requirement, I might lose the credit for the course”) instead of as pursuing gains (“if I fulfill the requirement, I will get the credit for the course”) 58 . Future research could test if the discounted value of a future loss is also associated with procrastination.

More work is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the observed association between temporal discounting and procrastination. First, it is possible that the association is due to a common cause. One candidate common cause is time perception 59 , 60 . The intuition is that a person who perceives a short period as longer tends to procrastinate because they think they have more time. The same person could be more likely to choose an immediate reward over a delayed reward because they perceive the delay to be longer.

Second, previous authors have distinguished between two forms of delay associated with procrastination: a delay in making a decision and a delay in implementing an action 61 , 62 . In our case, these would translate to choosing which research study to participate in and actually participating in it, respectively. Our empirical measure of procrastination does not distinguish between these two forms of delay. It would be interesting to test which form of delay is mainly responsible for the observed association between temporal discounting and procrastination.

In summary, we provided the first empirical evidence of an association between temporal discounting and procrastination in the real world. This finding not only suggested a potential cognitive mechanism underlying procrastination but also suggested a new approach to characterizing procrastination behavior and new interventions.

We sent email invitations with a link to our online study to all the students enrolled in the 2021 Introduction to Psychology course two weeks after the semester ended. In the email, we provided a broad description of the study’s aim, investigating the factors influencing student research participation. We did not disclose the specific focus of the study on procrastination.

Our online study included a delay discounting task to estimate the discount rate, a risky choice task, the Domain-Specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale 39 , and a set of custom-designed questions to estimate risk attitude jointly. It also included the Procrastination Assessment Scale for Students (PASS) 6 to test convergent validity. For exploratory analysis (details in the Supplement), we included surveys and custom-designed questions to address several aspects of procrastination in the research participation task. We included the Barratt Impulsivity Scale 63 , the Brief Self-Control Scale 64 , and perfectionism scales 65 , 66 to test their association with behavioral procrastination and whether they mediate the correlation between temporal discounting and procrastination. We also included custom-designed questions aimed at assessing participants’awareness of their procrastination levels in the task and their satisfaction with the way they allocated their time over the semester to fulfill the research participation requirement. Additionally, we included the Regret Elements Scale 67 to test whether high procrastinators regret the way they allocated their time to fulfill the requirement, the Causal Dimension Scale 68 to test attribution of procrastination and success in fulfilling the requirement, and the Reasons for Procrastination Scale 6 to identify the top-rated reasons for procrastination. All the tasks and surveys were counterbalanced in order, and tasks were presented before the surveys.

All participants gave informed consent prior to participating. Participants were compensated with $5 for their participation and had the opportunity to earn a bonus of up to $66 based on their choices during the tasks. This study was approved by New York University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB-FY2020-4262), and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was pre-registered on Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/4sxrw ).

Participant inclusion

The sample size of the online study was 194, which was 25.9% of the students who had been enrolled in the Introduction to Psychology course. To ensure that our measures of procrastination would not be confounded by the total number of work units completed, we only included the subset of participants who did not continue to do research sessions after they had met their 7-h requirement. For example, we would include a participant who, after completing 6.5 h, did a final research session to meet the requirement. However, we would exclude one who, after completing 7 h, did an additional session that was not required. This resulted in a total of 93 participants. Of the remaining 101 participants, 80 continued to do research sessions beyond the 7-h requirement, potentially to earn extra credit. The remaining 21 completed fewer than 7 h; in some cases, this was because they completed an alternative assignment (i.e., writing critique papers).

To test the hypothesis of correlation between temporal discounting and procrastination, out of 93 participants, we excluded 9 who either failed two or more of the five attention check questions or consistently chose one option in the delay discounting task, as that would make it impossible to determine their discount rate. To ensure that participants were not responding randomly, we conducted a quality control procedure 69 . We verified that participants’responses were influenced by task-relevant variables. This involved fitting a logistic regression model that included as predictors the immediate amount, the delayed amount, the delay, and the squares of these variables to each participant’s responses. The goodness of fit of the model was assessed using the coefficient of discrimination, and any participant with a value below 0.2 was considered a random respondent. No participants were excluded as random respondents. This left us with a final sample of 84 participants.

To test the hypothesis of correlation between risk attitude and procrastination, out of 93 participants, we excluded two subjects who either chose the objectively worse option in two or more of seven attention check trials or who consistently chose one option in the risky choice task, as that would be impossible to determine their risk attitude. Similarly to the delay discounting task, we conducted a quality control procedure to ensure that participants were not responding randomly. We verified that participants’ responses were influenced by task-relevant variables. This involved fitting a logistic regression model that included as predictors the winning amount of the lottery, the probability of winning the lottery, and the squares of these variables to each participant’s responses. The goodness of fit of the model was assessed using the coefficient of discrimination, and any participant with a value below 0.2 was considered a random respondent. No participants were excluded as random respondents. This left us with a final sample of 91 participants.

Delay discounting task

The delay discounting task consisted of 51 self-paced trials in which participants chose between receiving a smaller amount of money immediately or a larger amount after a specific number of days. The immediate reward ranged from $10 to $34, while the delayed reward was fixed at $25, $30, or $35, with delays ranging from 1 to 180 days. This choice set was designed to capture a broad range of discount rates evenly distributed in log space within the range of \([-1.6, -8.4]\) . It was adapted from Kirby’s choice set 31 and has been widely used in the temporal discounting literature 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 . To minimize any potential biases, we counterbalanced the position of the immediate reward on the screen (up or down). Additionally, we included five attention check trials in which participants were asked to choose between a larger immediate amount of money and a smaller amount with a delay.

We estimated temporal discount rates by fitting a hyperbolic choice model to the choice data of each participant. The utility of each option (immediate or delayed) is given by: \(U=\frac{v}{1+kD}\) , where U is the subjective discounted value, v is the monetary reward, D is a delay in days, and k is the individual discount rate. We used the softmax function to generate choice probabilities from option values.

where \(\text {Pr}_{\text {delayed}}\) is the probability that the participant chose the delayed option on a given trial, and \(\beta\) is the inverse temperature, which captures the stochasticity of the choice data. We used maximum-likelihood estimation to estimate the model parameters. We calculated the average goodness of fit as one minus the ratio between the log-likelihood of the model and that of a random-response model.

Risky-choice task

The risky-choice task consisted of 57 trials, each involving a choice between receiving $5 for sure and participating in a lottery where participants had a chance to win a larger amount with a certain probability, otherwise receiving $0. For example, one trial presented participants with a choice between $5 for sure and a 25% chance of winning $16 or a 75% chance of receiving $0. The larger amounts ranged from $6 to $66, and we used three different winning probabilities: 25%, 50%, and 75%. This choice set was adapted from a previous study 42 . To minimize any potential biases, we counterbalanced the position of the sure-bet option on the screen (left or right) and the associated color of the larger amount (blue or red). Additionally, we included seven attention check trials that presented participants with a choice between $5 for sure and a certain chance of receiving $4 or $5.

To help participants better understand the probabilities involved, the instructions included a visual representation of the choices. Each lottery image depicted a physical bag containing 100 poker chips, including red and blue chips. The size of the colored area and the number written inside indicated the number of chips of each color in the bag. The process of randomly drawing a chip was referred to as “playing the lottery.”

We estimated individual risk attitudes by fitting a power utility model to the trial-by-trial choice data. In this model, the utility of each option (safe or lottery) is given by \(U=pv^\alpha\) , where v is the dollar amount, p is the probability of winning, and \(\alpha\) is the individual’s risk attitude. A participant with \(\alpha >1\) is considered risk-seeking, \(\alpha =1\) is considered risk-neutral, or \(\alpha <1\) is considered risk-averse. Like in the delay discounting task, we used the softmax function to generate choice probabilities from option values.

where \(\text {Pr}_{\text {lottery}}\) is the probability that the subject chose the lottery on a given trial, and \(\gamma\) is the inverse temperature which captures the stochasticity of the choice data. We used maximum-likelihood estimation to estimate the model parameters.

Incentive compatibility

Both the delay discounting task and the risky choice task were incentive-compatible. Participants were offered a bonus: at the end of the study, their choice from a randomly selected trial in either the delay discounting task or the risky choice task determined the amount of this bonus. The bonus was provided as an electronic Amazon Gift Card. If the one randomly selected trial is from the delay discounting task, the timing of receiving the bonus depends on the chosen option. Specifically, for payment today, participants received the gift card on the same day. For delayed payments, participants received the gift card at a time corresponding to the delay associated with their chosen option. If the one randomly selected trial is from the risky choice task, if participants chose the sure bet in the selected trial, they would receive $5. However, if they chose the lottery, they would engage in the process of drawing a chip at random from a set of 100 chips. As the task was conducted online, we provided participants with a visual aid of the chip-drawing process. We displayed 100 chips and instructed participants to click on a chip to simulate the random draw. After clicking, the color of the chip would be revealed to indicate the result of the lottery.

Custom-designed questions to measure risk attitude toward postponing research participation

We designed three questions to measure the participants’risk perception and risk attitude regarding delaying their research participation until the end of the semester. The first question measured their perception of the risk associated with not being able to fulfill the research participation requirement by postponing it until the end of the semester. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the statement from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7): “I believe that postponing one’s research participation until the end of the semester increases the risk of not being able to fulfill the research participation requirement.”

The second and third questions aimed to measure the extent of aversion to the risk of not fulfilling the requirement due to delaying research participation until the end of the semester. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with the two statements from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7): “The increased risk of not being able to fulfill the research participation requirement due to postponing the research participation was motivating and exciting for me” (with reversed key) and “The increased risk of not being able to fulfill the research participation requirement due to postponing the research participation was stressful or anxiety-inducing for me.”

Data and code availability

Experimental stimuli, anonymized data, and scripts for analysis are available through the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/z548y/ ).

Harriott, J. & Ferrari, J. R. Prevalence of procrastination among samples of adults. Psychol. Rep. 78 , 611–616 (1996).

Article Google Scholar

Kachgal, M. M., Hansen, L. S. & Nutter, K. J. Academic procrastination prevention/intervention: Strategies and recommendations. J. Dev. Educ. 25 , 14 (2001).

Google Scholar

Martinez, S.-K., Meier, S. & Sprenger, C. Procrastination in the field: Evidence from tax filing. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 21 , 1119–1153 (2023).

Alfi, V., Parisi, G. & Pietronero, L. Conference registration: How people react to a deadline. Nat. Phys. 3 , 746–746 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Flandrin, P. An empirical model for electronic submissions to conferences. Adv. Complex Syst. 13 , 439–449 (2010).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Solomon, L. J. & Rothblum, E. D. Academic procrastination: Frequency and cognitive-behavioral correlates. J. Couns. Psychol. 31 , 503 (1984).

Rothblum, E. D., Solomon, L. J. & Murakami, J. Affective, cognitive, and behavioral differences between high and low procrastinators. J. Couns. Psychol. 33 , 387 (1986).

Steel, P., Brothen, T. & Wambach, C. Procrastination and personality, performance, and mood. Pers. Individ. Differ. 30 , 95–106 (2001).

Nguyen, B., Steel, P. & Ferrari, J. R. Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 21 , 388–399 (2013).

Tice, D. M. & Baumeister, R. F. Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress, and health: The costs and benefits of dawdling. Psychol. Sci. 8 , 454–458 (1997).

Sirois, F. M., Melia-Gordon, M. L. & Pychyl, T. A. I’ll look after my health, later: An investigation of procrastination and health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 35 , 1167–1184 (2003).

O’Donoghue, T. & Rabin, M. Doing it now or later. Am. Econ. Rev. 89 , 103–124 (1999).

O’Donoghue, T. & Rabin, M. Choice and procrastination. Q. J. Econ. 116 , 121–160 (2001).

Fischer, C. Read this paper later: Procrastination with time-consistent preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 46 , 249–269 (2001).

Steel, P. & König, C. J. Integrating theories of motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31 , 889–913 (2006).

Steel, P. The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol. Bull. 133 , 65 (2007).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Le Bouc, R. & Pessiglione, M. A neuro-computational account of procrastination behavior. Nat. Commun. 13 , 5639 (2022).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sutcliffe, K. R., Sedley, B., Hunt, M. J. & Macaskill, A. C. Relationships among academic procrastination, psychological flexibility, and delay discounting. Behav. Anal.: Res. Pract. 19 , 315 (2019).

Reuben, E., Sapienza, P. & Zingales, L. Procrastination and impatience. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 58 , 63–76 (2015).

Xin, Y., Xu, P., Aleman, A., Luo, Y. & Feng, T. Intrinsic prefrontal organization underlies associations between achievement motivation and delay discounting. Brain Struct. Funct. 225 , 511–518 (2020).

Lee, N. C. et al. Academic motivation mediates the influence of temporal discounting on academic achievement during adolescence. Trends Neurosci. Educ. 1 , 43–48 (2012).

Sokolowski, M. B. & Tonneau, F. Student procrastination on an e-learning platform: From individual discounting to group behavior. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 44 , 621–640 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Howell, A. J., Watson, D. C., Powell, R. A. & Buro, K. Academic procrastination: The pattern and correlates of behavioural postponement. Pers. Individ. Differ. 40 , 1519–1530 (2006).

Pittman, T. S., Tykocinski, O. E., Sandman-Keinan, R. & Matthews, P. A. When bonuses backfire: An inaction inertia analysis of procrastination induced by a missed opportunity. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 21 , 139–150 (2008).

McElroy, B. W. & Lubich, B. H. Predictors of course outcomes: Early indicators of delay in online classrooms. Distance Educ. 34 , 84–96 (2013).

Lim, J. M. Predicting successful completion using student delay indicators in undergraduate self-paced online courses. Distance Educ. 37 , 317–332 (2016).

Buehler, R. & Griffin, D. Planning, personality, and prediction: The role of future focus in optimistic time predictions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 92 , 80–90 (2003).

Konradt, U., Ellwart, T. & Gevers, J. Wasting effort or wasting time? A longitudinal study of pacing styles as a predictor of academic performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 88 , 102003 (2021).

Vangsness, L. & Young, M. E. Turtle, task ninja, or time waster? Who cares? Traditional task-completion strategies are overrated. Psychol. Sci. 31 , 306–315 (2020).

Steel, P., Svartdal, F., Thundiyil, T. & Brothen, T. Examining procrastination across multiple goal stages: A longitudinal study of temporal motivation theory. Front. Psychol. 9 , 327 (2018).

Kirby, K. N., Petry, N. M. & Bickel, W. K. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 128 , 78 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Senecal, N., Wang, T., Thompson, E. & Kable, J. W. Normative arguments from experts and peers reduce delay discounting. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 7 , 568–589 (2012).

Linda, Q. Y. et al. Steeper discounting of delayed rewards in schizophrenia but not first-degree relatives. Psychiatry Res. 252 , 303–309 (2017).

Parthasarathi, T., McConnell, M. H., Luery, J. & Kable, J. W. The vivid present: Visualization abilities are associated with steep discounting of future rewards. Front. Psychol. 8 , 289 (2017).

Lempert, K. M. et al. Neural and behavioral correlates of episodic memory are associated with temporal discounting in older adults. Neuropsychologia 146 , 107549 (2020).

Bulley, A., Lempert, K. M., Conwell, C., Irish, M. & Schacter, D. L. Intertemporal choice reflects value comparison rather than self-control: Insights from confidence judgements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 377 , 20210338 (2022).

Batistuzzo, M. C. et al. Cross-national harmonization of neurocognitive assessment across five sites in a global study. Neuropsychology 37 , 284 (2023).

Keinan, R. & Bereby-Meyer, Y. leaving it to chance-passive risk taking in everyday life. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 7 , 705–715 (2012).

Blais, A.-R. & Weber, E. U. A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 1 , 33–47 (2006).

Lay, C. H. At last, my research article on procrastination. J. Res. Pers. 20 , 474–495 (1986).

Holt, C. A. & Laury, S. K. Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 92 , 1644–1655 (2002).

Lopez-Guzman, S., Konova, A. B., Louie, K. & Glimcher, P. W. Risk preferences impose a hidden distortion on measures of choice impulsivity. PLoS ONE 13 , e0191357 (2018).

Lubbers, M. J., Van Der Werf, M. P., Kuyper, H. & Hendriks, A. J. Does homework behavior mediate the relation between personality and academic performance?. Learn. Individ. Differ. 20 , 203–208 (2010).

Diver, P. & Martinez, I. Moocs as a massive research laboratory: Opportunities and challenges. Distance Educ. 36 , 5–25 (2015).

Woolley, K. & Fishbach, A. For the fun of it: Harnessing immediate rewards to increase persistence in long-term goals. J. Consum. Res. 42 , 952–966 (2016).

Woolley, K. & Fishbach, A. Immediate rewards predict adherence to long-term goals. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43 , 151–162 (2017).

Lieder, F., Chen, O. X., Krueger, P. M. & Griffiths, T. L. Cognitive prostheses for goal achievement. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3 , 1096–1106 (2019).

Rung, J. M. & Madden, G. J. Experimental reductions of delay discounting and impulsive choice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147 , 1349 (2018).

Scholten, H. et al. Behavioral trainings and manipulations to reduce delay discounting: A systematic review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26 , 1803–1849 (2019).

Rad, H. S., Samadi, S., Sirois, F. M. & Goodarzi, H. Mindfulness intervention for academic procrastination: A randomized control trial. Learn. Individ. Differ. 101 , 102244 (2023).

Schutte, N. S. & del Pozo de Bolger, A. Greater mindfulness is linked to less procrastination. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 5 , 1–12 (2020).

Li, L. & Mu, L. Effects of mindfulness training on psychological capital, depression, and procrastination of the youth demographic. Iran. J. Public Health 49 , 1692 (2020).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dionne, F. Using acceptance and mindfulness to reduce procrastination among university students: Results from a pilot study. Rev. Prâksis 1 , 8–20 (2016).

Rebetez, M. M. L., Barsics, C., Rochat, L., D’Argembeau, A. & Van der Linden, M. Procrastination, consideration of future consequences, and episodic future thinking. Conscious. Cogn. 42 , 286–292 (2016).

Lempert, K. M., Steinglass, J. E., Pinto, A., Kable, J. W. & Simpson, H. B. Can delay discounting deliver on the promise of RDoC?. Psychol. Med. 49 , 190–199 (2019).

Oguchi, M., Takahashi, T., Nitta, Y. & Kumano, H. Moderating effect of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder tendency on the relationship between delay discounting and procrastination in young adulthood. Heliyon 9 , e14834 (2023).

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world?. Behav. Brain Sci. 33 , 61–83 (2010).

Thaler, R. Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Econ. Lett. 8 , 201–207 (1981).

Baumann, A. A. & Odum, A. L. Impulsivity, risk taking, and timing. Behav. Proc. 90 , 408–414 (2012).

Jackson, T., Fritch, A., Nagasaka, T. & Pope, L. Procrastination and perceptions of past, present, and future. Indiv. Differ. Res. 1 , 17–28 (2003).

Steel, P. Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist?. Pers. Individ. Differ. 48 , 926–934 (2010).

Gollwitzer, P. M. The Volitional Benefits of Planning. The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior (Guilford Press, New York, 1996).

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51 , 768–774 (1995).

Tangney, J. P., Boone, A. L. & Baumeister, R. F. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success, in Self-regulation and Self-control 173–212 (Routledge, 2018).

Hewitt, P. L. & Flett, G. L. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60 , 456 (1991).

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C. & Rosenblate, R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 14 , 449–468 (1990).

Buchanan, J., Summerville, A., Lehmann, J. & Reb, J. The regret elements scale: Distinguishing the affective and cognitive components of regret. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 11 , 275–286 (2016).

Russell, D. The causal dimension scale: A measure of how individuals perceive causes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 42 , 1137 (1982).

Pehlivanova, M. et al. Diminished cortical thickness is associated with impulsive choice in adolescence. J. Neurosci. 38 , 2471–2481 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Brenda Woodford-Febres for the arduous work of extracting the students’research participation data from New York University’s Sona system.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York City, 10003, USA

Pei Yuan Zhang & Wei Ji Ma

Department of Psychology, New York University, New York City, 10003, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.Y.Z. designed research; P.Y.Z. performed research; P.Y.Z. and W.J.M. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; P.Y.Z. analyzed data; P.Y.Z. wrote the original draft. W.J.M. edited the draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pei Yuan Zhang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zhang, P.Y., Ma, W.J. Temporal discounting predicts procrastination in the real world. Sci Rep 14 , 14642 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65110-4

Download citation

Received : 01 March 2024

Accepted : 17 June 2024

Published : 25 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65110-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Temporal discounting

- Procrastination

- Real-world behavior

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

What Research Has Been Conducted on Procrastination? Evidence From a Systematical Bibliometric Analysis

- February 2022

- Xi'an Jiaotong University

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Aleksandra Cincio

- Siying Chen

- Zhixiong Tan

- Maozhi Chen

- Jingwei Han

- Anna Jochmann

- Burkhard Gusy

- Tino Lesener

- Christine Wolter

- Meihui Song

- Suada Peštek

- Gholamreza Nabavi

- Seyyed Yusuf Ahadi Serkani

- Ahmad Yaqubnejad

- Seyedeh Atefeh Hosseini

- Lianyong Ding

- Hamsa Hameed Ahmed

- Int J Educ Vocat Guid

- Nimrod Levin

- CURR PSYCHOL

- Tingyong Feng

- Jianhua Hou

- Felix Schröter

- ADDICT BEHAV

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Procrastination among university students: differentiating severe cases in need of support from less severe cases.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

- 2 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

- 3 Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 4 Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

- 5 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Paderborn University, Paderborn, Germany

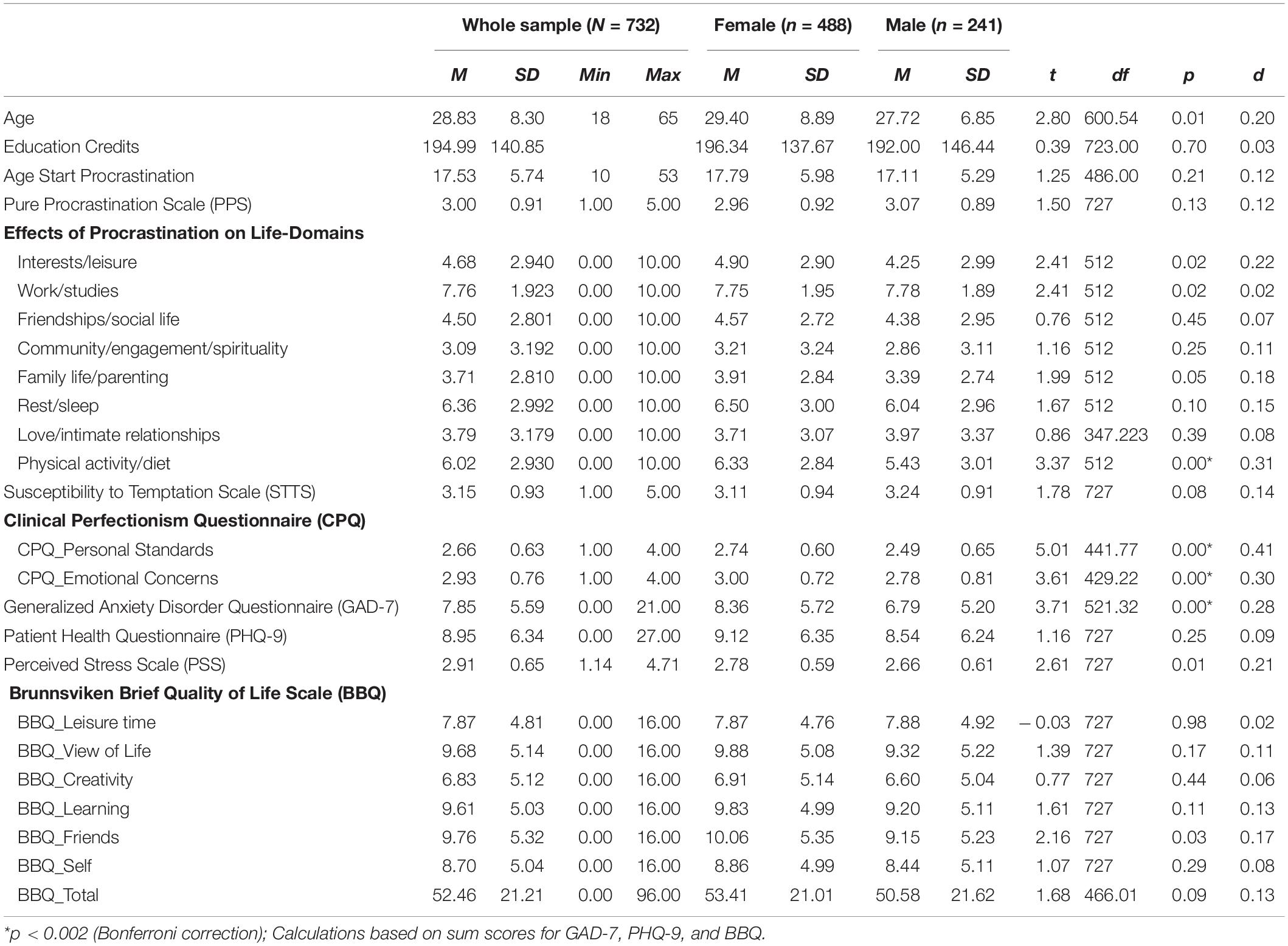

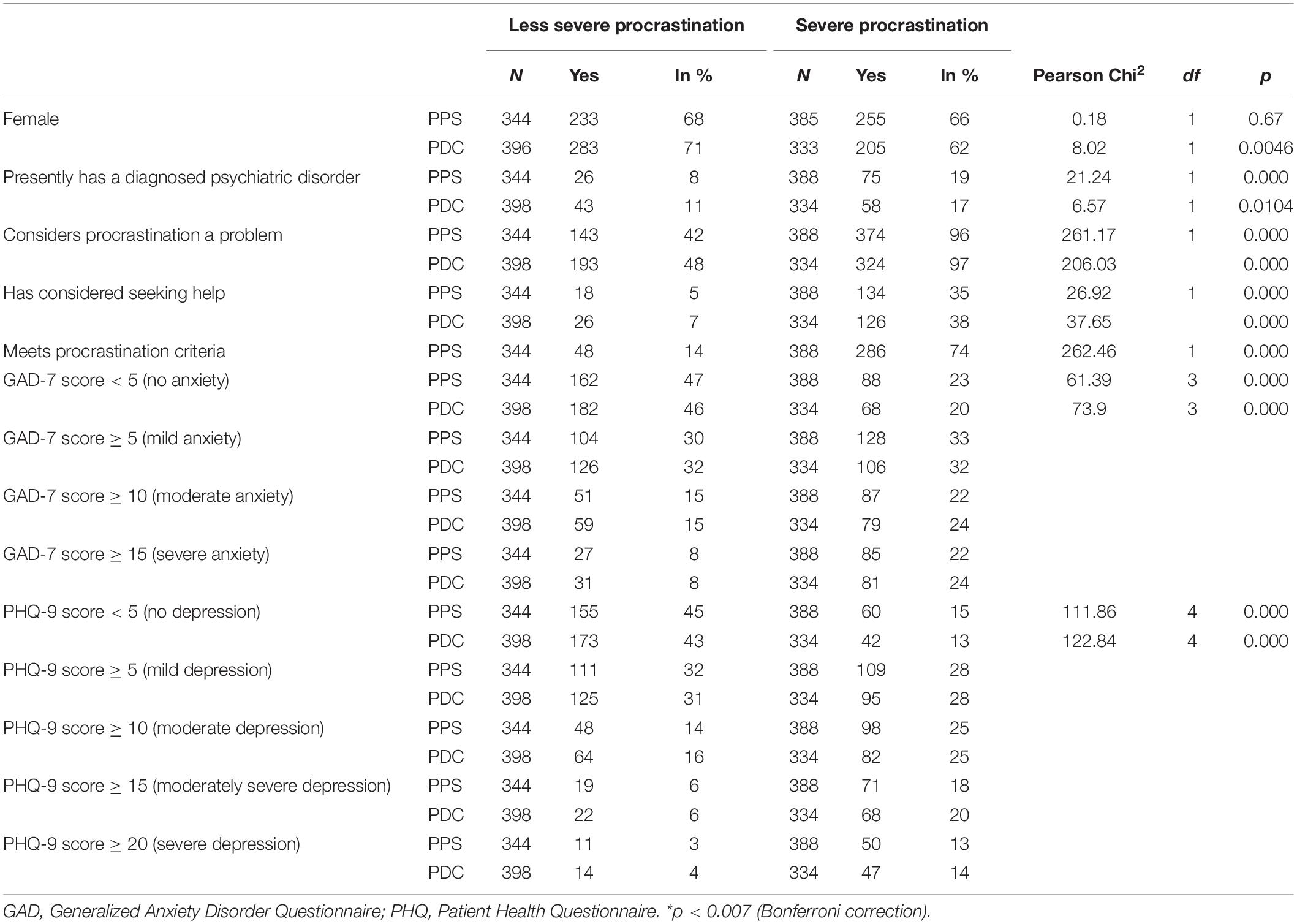

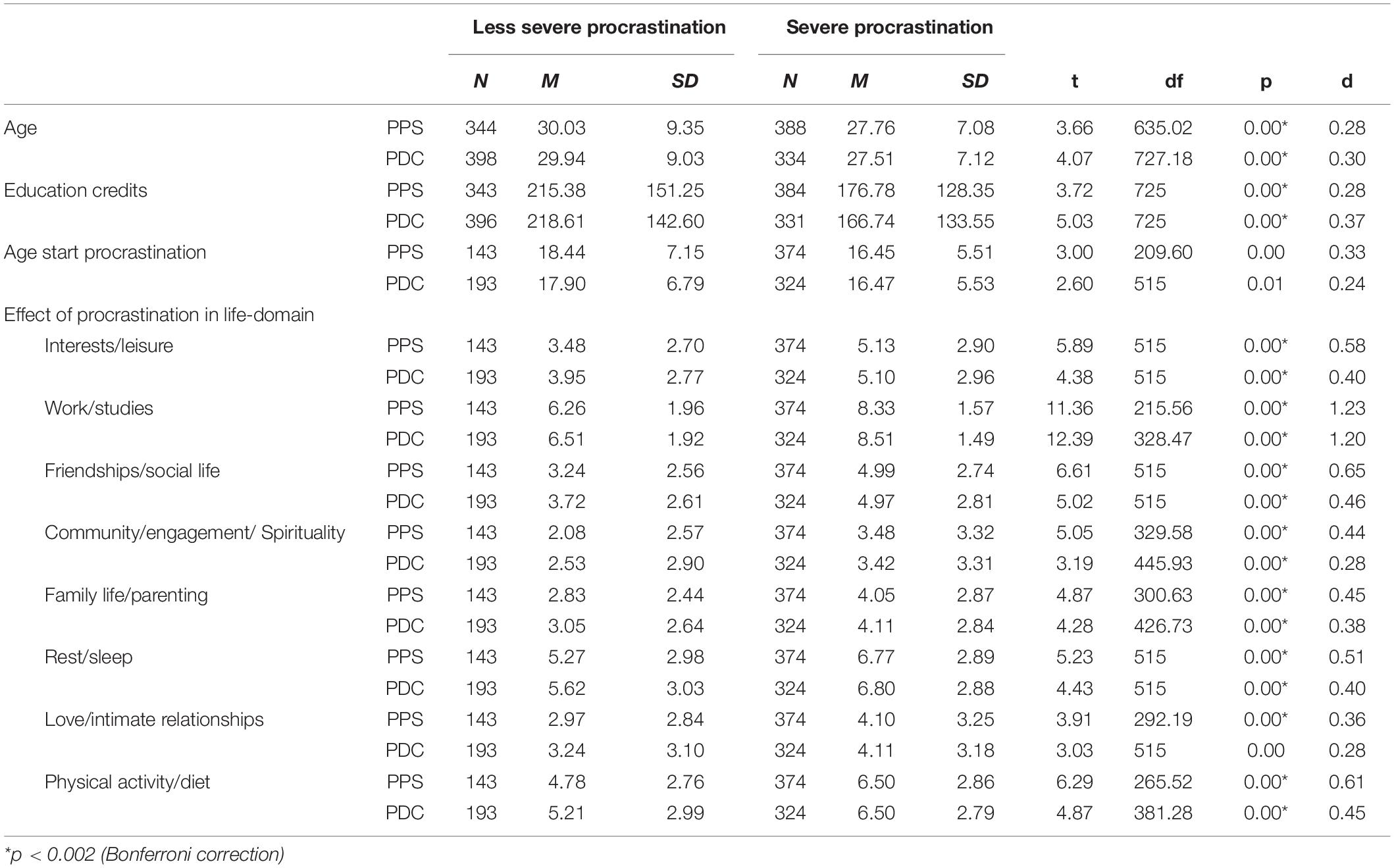

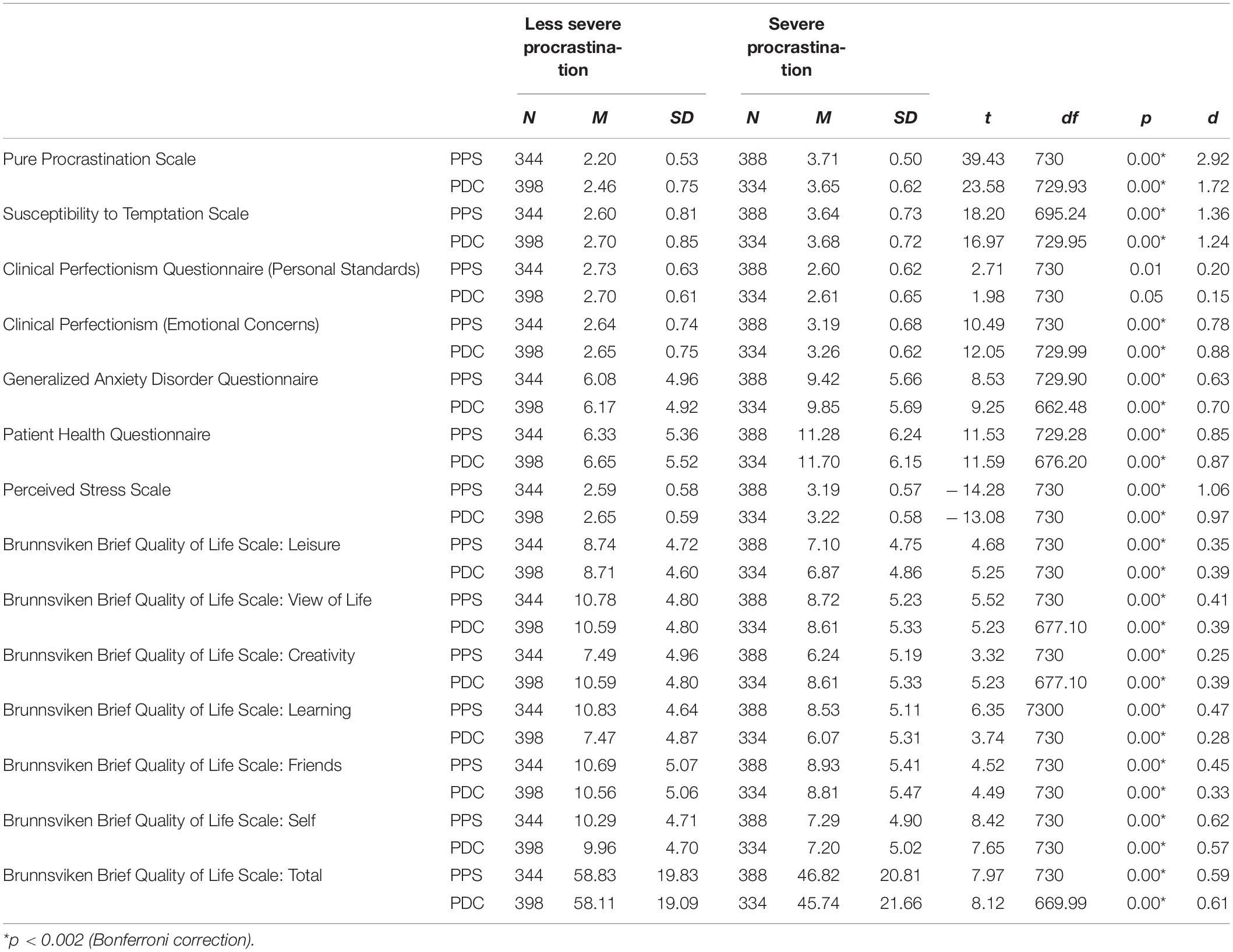

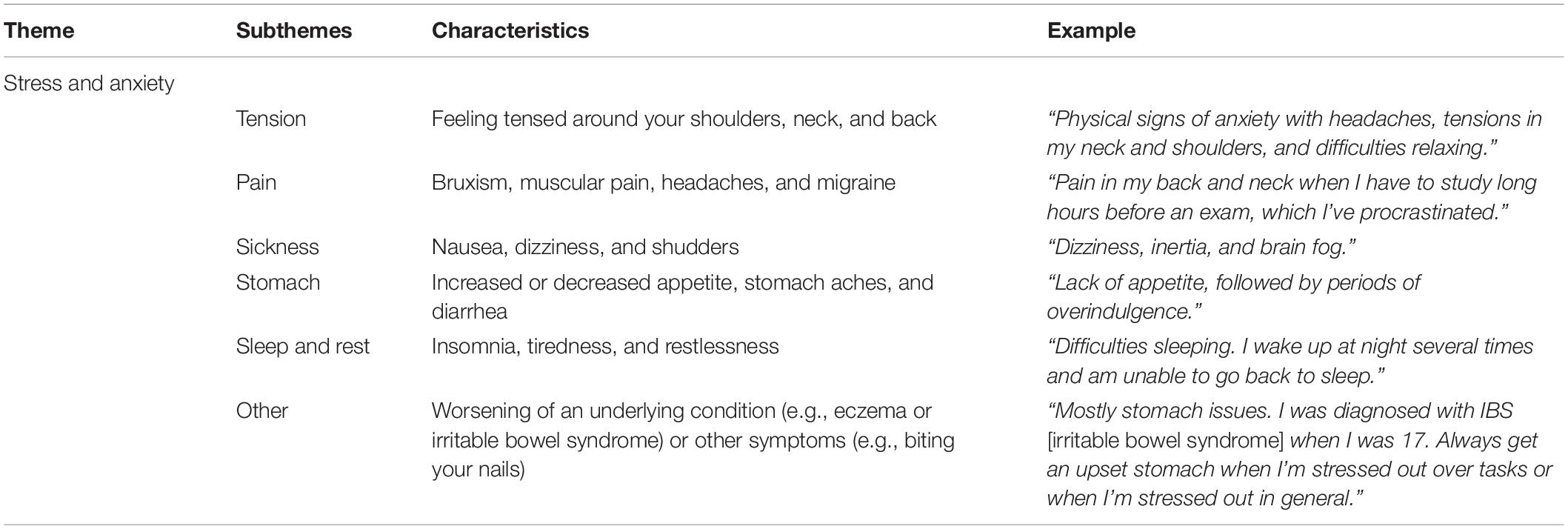

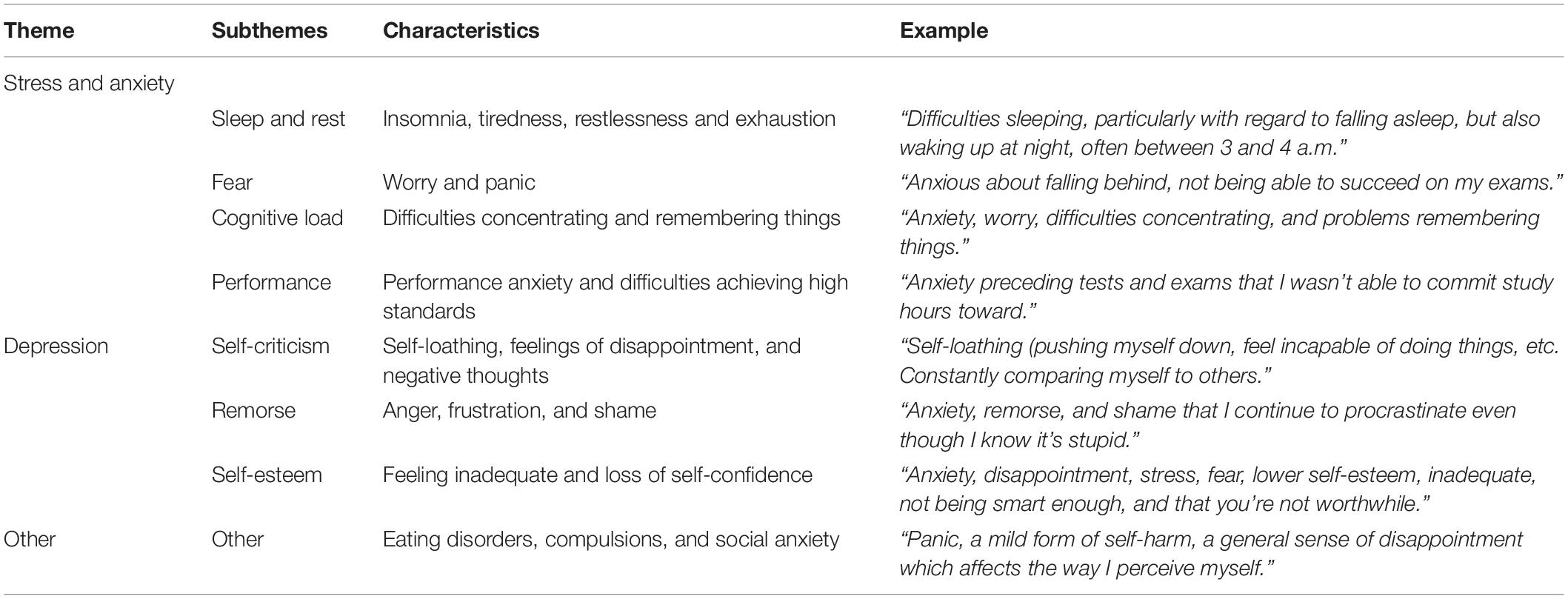

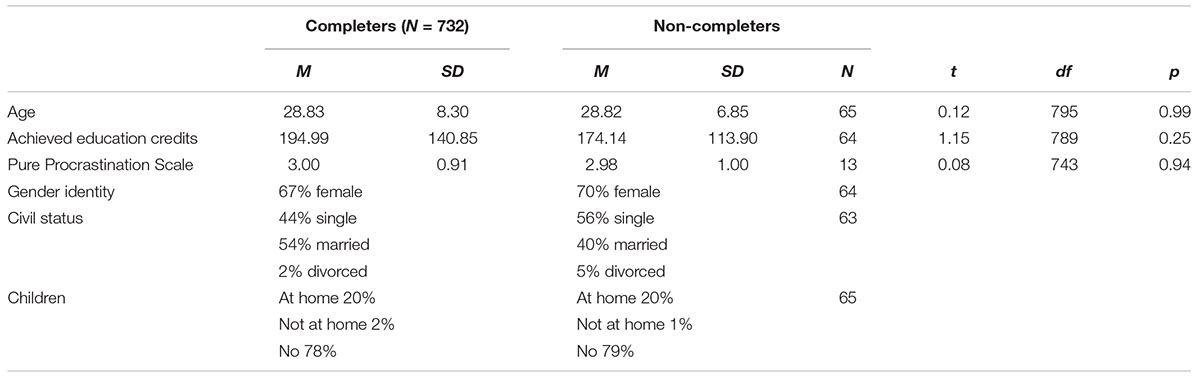

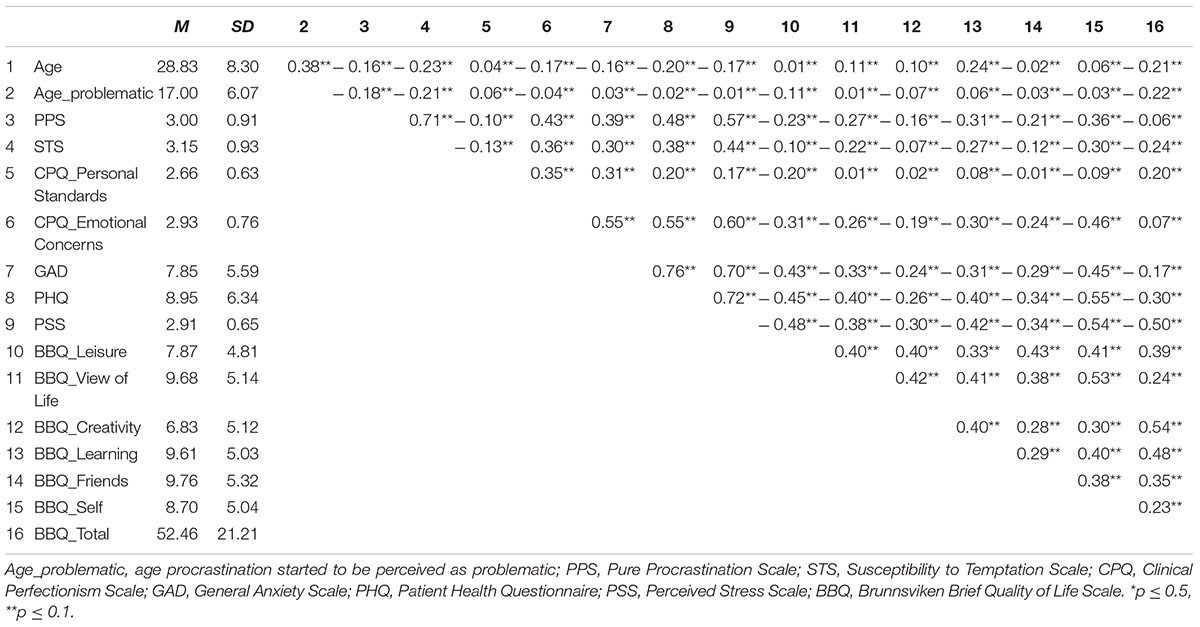

Procrastination refers to voluntarily postponing an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for this delay, and students are considered to be especially negatively affected. According to estimates in the literature, at least half of the students believe procrastination impacts their academic achievements and well-being. As of yet, evidence-based ideas on how to differentiate severe from less severe cases of procrastination in this population do not exist, but are important in order to identify those students in need of support. The current study recruited participants from different universities in Sweden to participate in an anonymous online survey investigating self-rated levels of procrastination, impulsivity, perfectionism, anxiety, depression, stress, and quality of life. Furthermore, diagnostic criteria for pathological delay (PDC) as well as self-report items and open-ended questions were used to determine the severity of their procrastination and its associated physical and psychological issues. In total, 732 participants completed the survey. A median-split on the Pure Procrastination Scale (PPS) and the responses to the PDC were used to differentiate two groups; “less severe procrastination” (PPS ≤ 2.99; n = 344; 67.7% female; M age = 30.03; SD age = 9.35), and “severe procrastination” (PPS ≥ 3.00; n = 388; 66.2% female; M age = 27.76; SD age = 7.08). For participants in the severe group, 96–97% considered procrastination to a problem, compared to 42–48% in the less severe group. The two groups also differed with regard to considering seeking help for procrastination, 35–38% compared to 5–7%. Participants in the severe group also reported more problems of procrastination in different life domains, greater symptoms of psychological issues, and lower quality of life. A thematic analysis of the responses on what physical issues were related to procrastination revealed that these were characterized by stress and anxiety, e.g., tension, pain, and sleep and rest, while the psychological issues were related to stress and anxiety, but also depression, e.g., self-criticism, remorse, and self-esteem. The current study recommends the PPS to be used as an initial screening tool, while the PDC can more accurately determine the severity level of procrastination for a specific individual.

Introduction

In academia, procrastination is a well-known, almost commonplace phenomenon. Students often delay tasks and activities inherent to learning and studying, despite knowing that they will be worse off because of the delay (cf. Steel, 2007 ; Steel and Klingsieck, 2016 ). For some students, academic procrastination can be specific to a situation (i.e., state procrastination), for others it takes on features of a habit or a disposition (i.e., trait procrastination). Studies estimate that almost all students engage in procrastination once in a while, while 75% consider themselves habitual procrastinators ( Steel, 2007 ). For almost half of these habitual procrastinators, procrastination is a real and persistent problem ( Steel, 2007 ), and something they would like to tackle ( Grunschel and Schopenhauer, 2015 ). It can be assumed, however, that not all of them seek help due to the self-regulative problems inherent to procrastination, and, even more so, due to feelings of shame associated with procrastination ( Giguère et al., 2016 ).

In light of the negative consequences, procrastination can have for academic achievement (e.g., Kim and Seo, 2015 ), and well-being (cf. Sirios and Pychyl, 2016 ), it seems important to screen for cases of severe procrastination in a student population in order to offer the support needed. In the case of students who do seek help in student health centers, it is also helpful to see whether they represent a case of severe or less severe procrastination so that support can be tailored to their specific needs.

The aim of the current study is, thus, to differentiate between students who might be in need of professional help from those with less pressing concerns. This is done by determining what characterizes severe and less severe procrastinators with regard to their level of anxiety, depression, stress, quality of life, impulsivity, perfectionism, and demographic variables. Procrastination itself is also assessed by two different self-report measures with the intention of proposing ways of screening in a student population. This could help therapists identify those in need of guidance so that effective interventions can be introduced. For college and university students this would be particularly useful as they find themselves in a setting where procrastination is particularly endemic, often lack the necessary resources or strategies to overcome problems on their own, and procrastination can have dire consequences not only for their academic achievements but also physical and psychological well-being.

Conceptual Framework

Academic procrastination.

The prominent definition of procrastination as “to voluntarily delay an intended course of action despite expecting to be worse off for the delay” ( Steel, 2007 , p. 66) reflects two important aspects of the phenomenon. First, procrastination is a post-decisional phenomenon in goal-directed behavior in that an intention (e.g., to study for an exam) has been formed. Second, procrastination is acratic in nature since individuals put of the intended course of action contrary to knowing better. This acratic nature is reflected by feelings such as regret, shame, guilt, worry, and anxiety (e.g., Giguère et al., 2016 ). It is important to acknowledge that a delay is not procrastination if it is strategic or results from causes not under the control of the individual (cf. Klingsieck, 2013 ). Taking these aspects – post-decisional, acratic, and non-strategic – together, suggests that procrastination is a failure in self-regulation (cf. Steel, 2007 ), This is the most popular conceptualization of procrastination in the literature. In fact, the dispositional, the motivational-volitional, the clinical, and the situational perspective on procrastination can be boiled down to this understanding of procrastination ( Klingsieck, 2013 ). As for students, while academic procrastination is just a little nuisance for some, it entails serious problems for others.

Procrastination’s Link to Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Quality of Life

Procrastination is associated with negative consequences concerning performance as well as physical and psychological well-being. However, although never a particularly helpful behavior, the relationship with performance is probably not as strong as most would expect. Among students, the correlation with academic achievement is weak, r s = –0.13 to –0.19 ( Steel, 2007 ; Kim and Seo, 2015 ), and perhaps not the main reason for why individuals regard procrastination as a problem. Instead, it might be its effects on physical and psychological well-being that eventually makes someone seek professional help ( Rozental and Carlbring, 2014 ). In a qualitative study of 36 students, for instance, the most frequently reported negative consequences were anger, anxiety, feelings of discomfort, shame, sadness, feeling remorse, mental stress, and negative self-concept ( Grunschel et al., 2013 ). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the link between procrastination and symptoms of psychiatric conditions have also found a weak but nonetheless clinically meaningful correlation with depression, r s = 0.28 to 0.30 ( van Eerde, 2003 ; Steel, 2007 ). The same also goes for anxiety, r = 0.22 ( van Eerde, 2003 ). Studies investigating the connection between self-report measures in different populations have demonstrated stronger correlations, such as Rozental et al. (2015) in a clinical trial of adults seeking treatment for procrastination ( n = 710), r = 0.35 for depression and r = 0.42 for anxiety. Similar results were also obtained by Beutel et al. (2016) in an adult community sample ( n = 2527), r = 0.36 for depression and r = 0.32 for anxiety. Although both lower mood and increased unrest can, in themselves, cause procrastination, it is assumed that procrastination also creates a downward spiral characterized by negative thoughts and feelings ( Rozental and Carlbring, 2014 ).

Apart from depression and anxiety, students generally tend to regard procrastination as something stressful. Stead et al. (2010) investigated this association using self-report measures in a sample of students ( n = 200), demonstrating a weak but nonetheless significant correlation between procrastination and stress, r = 0.20. Similar findings were reported by Sirois et al. (2003) for students ( n = 122), and Sirois (2007) for a sample of community-dwelling adults ( n = 254), r s = 0.13 to 0.20. Further, Beutel et al. (2016) found somewhat stronger correlations with stress, r = 0.39, as well as with burnout, r = 0.27. Stress might also play a role as mediator between procrastination and illness, as proposed by the so-called procrastination-health model by Sirois (2007) , implying that procrastination not only leads to more stress, but that the increase in stress in turn leads to many physical issues. Meanwhile, in terms of quality of life and satisfaction with life, procrastination exhibits a weak negative correlation, r = −0.32 ( Rozental et al., 2014 ), and r = −0.35 ( Beutel et al., 2016 ), meaning that procrastination could take its toll on how one appreciates current circumstances.

However, despite the fact that procrastination might be affecting physical and psychological well-being negatively, it is still unclear when it goes from being a more routine form of postponement to becoming something that warrants support, for instance in the realm of counseling or therapy. The literature suggests that as many as 20% of the adult population could be regarded as “chronic procrastinators” ( Harriot and Ferrari, 1996 , p. 611), a number that is easily surpassed by the 32% of students that were characterized as “severe, general procrastinators” ( Day et al., 2000 , p. 126). Students are generally considered worse-off when it comes to recurrently and problematically delaying important curricular activities, with more than half of this population stating that they would like to reduce their procrastination ( Solomon and Rothblum, 1984 ). Still, all of these rates rely on arbitrary cutoffs on specific self-report measures, such as exceeding a certain score, or do not define what is meant by procrastination, which may not correspond to something that requires clinical attention ( Rozental and Carlbring, 2014 ). Establishing a more valid cutoff is therefore needed in order to separate the less severe cases of procrastination from those having problems to the degree that it severely affects everyday life.

Procrastination’s Link to Impulsivity and Perfectionism

Two other variables that are frequently explored in relation to procrastination involve impulsivity and perfectionism. These might be especially pertinent to examine in the context of students who, due to their age, are more impulsive and engage in more reckless behaviors, such as binge drinking ( Lannoy et al., 2017 ), but also tend to perceive the relentless pursuit of high standards as socially desirable despite the fact it can become maladaptive ( Stoeber and Hotham, 2013 ). Research has found that impulsivity is moderately correlated with procrastination, r = 0.41 ( Steel, 2007 ), making it one of the strongest predictors among the personality traits. A twin study by Gustavson et al. (2014) confirmed this association ( n = 663), suggesting that the genetic correlation between impulsivity and procrastination is perfect, r = 1.0. However, this was later questioned by a twin study with a much larger sample ( n = 2012), demonstrating a weak but nonetheless noteworthy correlation, r = 0.29 ( Loehlin and Martin, 2014 ). Rozental et al. (2014) also examined the link between impulsivity and procrastination, but using a self-report measure of susceptibility to temptation, indicating a moderate correlation, r = 0.53. At its core, impulsivity shares many features with procrastination (i.e., self-regulatory failure), making it reasonable to expect a strong connection between the two constructs. Meanwhile, the relationship between perfectionism and procrastination has been disputed. Originally, Steel (2007) demonstrated a non-significant correlation, r = −0.03. Similarly, the correlation by van Eerde (2003) was weak, r = 0.12. This goes against the clinical impression by many therapists that perfectionism often leads to procrastination. However, in both of these cases perfectionism was perceived as a unidimensional construct. There is currently consensus that perfectionism in fact has two higher-order dimensions; (1) perfectionistic strivings, i.e., setting high standards and expecting no less than perfection from yourself, and (2) perfectionistic concerns, i.e., being highly self-critical and overly concerned about others’ perception of you, and having a hard time enjoying your achievements. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis separating these two demonstrated a more complex relationship with procrastination ( Sirois et al., 2017 ). Perfectionistic strivings had a weak negative correlation with procrastination, r = −0.22, while perfectionistic concerns had a weak positive correlation with procrastination, r = 0.23. In other words, setting and striving for high standards might actually be associated with less procrastination, while the more neurotic aspects of perfectionism are related to more procrastination.

To what extent impulsivity and perfectionism might differ between cases of less severe and severe cases of procrastination is currently unknown. However, just as physical and psychological well-being is expected to be more negatively affected among those who exhibit higher levels of procrastination, impulsivity and perfectionism should be more pronounced.

The Current Study

The aim of the current study is to investigate all of these aspects in a sample of students with the purpose of trying to differentiate between those who might be in need for professional help from those with less pressing matters. The idea is to outline their respective characteristics with regard to scores on self-report measures on anxiety, depression, stress, quality of life, impulsivity, and perfectionism, and demographics. Procrastination itself is assessed by two different self-report measures. This first measure is the Pure Procrastination Scale (PPS; Steel, 2010 ) which is a widely used self-report measure. The second measure are the recently proposed diagnostic criteria for pathological delay (Pathological Delay Criteria; PDC; Höcker et al., 2017 ).