- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Questions

Definition:

Research questions are the specific questions that guide a research study or inquiry. These questions help to define the scope of the research and provide a clear focus for the study. Research questions are usually developed at the beginning of a research project and are designed to address a particular research problem or objective.

Types of Research Questions

Types of Research Questions are as follows:

Descriptive Research Questions

These aim to describe a particular phenomenon, group, or situation. For example:

- What are the characteristics of the target population?

- What is the prevalence of a particular disease in a specific region?

Exploratory Research Questions

These aim to explore a new area of research or generate new ideas or hypotheses. For example:

- What are the potential causes of a particular phenomenon?

- What are the possible outcomes of a specific intervention?

Explanatory Research Questions

These aim to understand the relationship between two or more variables or to explain why a particular phenomenon occurs. For example:

- What is the effect of a specific drug on the symptoms of a particular disease?

- What are the factors that contribute to employee turnover in a particular industry?

Predictive Research Questions

These aim to predict a future outcome or trend based on existing data or trends. For example :

- What will be the future demand for a particular product or service?

- What will be the future prevalence of a particular disease?

Evaluative Research Questions

These aim to evaluate the effectiveness of a particular intervention or program. For example:

- What is the impact of a specific educational program on student learning outcomes?

- What is the effectiveness of a particular policy or program in achieving its intended goals?

How to Choose Research Questions

Choosing research questions is an essential part of the research process and involves careful consideration of the research problem, objectives, and design. Here are some steps to consider when choosing research questions:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the problem or issue that you want to study. This could be a gap in the literature, a social or economic issue, or a practical problem that needs to be addressed.

- Conduct a literature review: Conducting a literature review can help you identify existing research in your area of interest and can help you formulate research questions that address gaps or limitations in the existing literature.

- Define the research objectives : Clearly define the objectives of your research. What do you want to achieve with your study? What specific questions do you want to answer?

- Consider the research design : Consider the research design that you plan to use. This will help you determine the appropriate types of research questions to ask. For example, if you plan to use a qualitative approach, you may want to focus on exploratory or descriptive research questions.

- Ensure that the research questions are clear and answerable: Your research questions should be clear and specific, and should be answerable with the data that you plan to collect. Avoid asking questions that are too broad or vague.

- Get feedback : Get feedback from your supervisor, colleagues, or peers to ensure that your research questions are relevant, feasible, and meaningful.

How to Write Research Questions

Guide for Writing Research Questions:

- Start with a clear statement of the research problem: Begin by stating the problem or issue that your research aims to address. This will help you to formulate focused research questions.

- Use clear language : Write your research questions in clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms that may be unfamiliar to your readers.

- Be specific: Your research questions should be specific and focused. Avoid broad questions that are difficult to answer. For example, instead of asking “What is the impact of climate change on the environment?” ask “What are the effects of rising sea levels on coastal ecosystems?”

- Use appropriate question types: Choose the appropriate question types based on the research design and objectives. For example, if you are conducting a qualitative study, you may want to use open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed responses.

- Consider the feasibility of your questions : Ensure that your research questions are feasible and can be answered with the resources available. Consider the data sources and methods of data collection when writing your questions.

- Seek feedback: Get feedback from your supervisor, colleagues, or peers to ensure that your research questions are relevant, appropriate, and meaningful.

Examples of Research Questions

Some Examples of Research Questions with Research Titles:

Research Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health

- Research Question : What is the relationship between social media use and mental health, and how does this impact individuals’ well-being?

Research Title: Factors Influencing Academic Success in High School

- Research Question: What are the primary factors that influence academic success in high school, and how do they contribute to student achievement?

Research Title: The Effects of Exercise on Physical and Mental Health

- Research Question: What is the relationship between exercise and physical and mental health, and how can exercise be used as a tool to improve overall well-being?

Research Title: Understanding the Factors that Influence Consumer Purchasing Decisions

- Research Question : What are the key factors that influence consumer purchasing decisions, and how do these factors vary across different demographics and products?

Research Title: The Impact of Technology on Communication

- Research Question : How has technology impacted communication patterns, and what are the effects of these changes on interpersonal relationships and society as a whole?

Research Title: Investigating the Relationship between Parenting Styles and Child Development

- Research Question: What is the relationship between different parenting styles and child development outcomes, and how do these outcomes vary across different ages and developmental stages?

Research Title: The Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Treating Anxiety Disorders

- Research Question: How effective is cognitive-behavioral therapy in treating anxiety disorders, and what factors contribute to its success or failure in different patients?

Research Title: The Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity

- Research Question : How is climate change affecting global biodiversity, and what can be done to mitigate the negative effects on natural ecosystems?

Research Title: Exploring the Relationship between Cultural Diversity and Workplace Productivity

- Research Question : How does cultural diversity impact workplace productivity, and what strategies can be employed to maximize the benefits of a diverse workforce?

Research Title: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare

- Research Question: How can artificial intelligence be leveraged to improve healthcare outcomes, and what are the potential risks and ethical concerns associated with its use?

Applications of Research Questions

Here are some of the key applications of research questions:

- Defining the scope of the study : Research questions help researchers to narrow down the scope of their study and identify the specific issues they want to investigate.

- Developing hypotheses: Research questions often lead to the development of hypotheses, which are testable predictions about the relationship between variables. Hypotheses provide a clear and focused direction for the study.

- Designing the study : Research questions guide the design of the study, including the selection of participants, the collection of data, and the analysis of results.

- Collecting data : Research questions inform the selection of appropriate methods for collecting data, such as surveys, interviews, or experiments.

- Analyzing data : Research questions guide the analysis of data, including the selection of appropriate statistical tests and the interpretation of results.

- Communicating results : Research questions help researchers to communicate the results of their study in a clear and concise manner. The research questions provide a framework for discussing the findings and drawing conclusions.

Characteristics of Research Questions

Characteristics of Research Questions are as follows:

- Clear and Specific : A good research question should be clear and specific. It should clearly state what the research is trying to investigate and what kind of data is required.

- Relevant : The research question should be relevant to the study and should address a current issue or problem in the field of research.

- Testable : The research question should be testable through empirical evidence. It should be possible to collect data to answer the research question.

- Concise : The research question should be concise and focused. It should not be too broad or too narrow.

- Feasible : The research question should be feasible to answer within the constraints of the research design, time frame, and available resources.

- Original : The research question should be original and should contribute to the existing knowledge in the field of research.

- Significant : The research question should have significance and importance to the field of research. It should have the potential to provide new insights and knowledge to the field.

- Ethical : The research question should be ethical and should not cause harm to any individuals or groups involved in the study.

Purpose of Research Questions

Research questions are the foundation of any research study as they guide the research process and provide a clear direction to the researcher. The purpose of research questions is to identify the scope and boundaries of the study, and to establish the goals and objectives of the research.

The main purpose of research questions is to help the researcher to focus on the specific area or problem that needs to be investigated. They enable the researcher to develop a research design, select the appropriate methods and tools for data collection and analysis, and to organize the results in a meaningful way.

Research questions also help to establish the relevance and significance of the study. They define the research problem, and determine the research methodology that will be used to address the problem. Research questions also help to determine the type of data that will be collected, and how it will be analyzed and interpreted.

Finally, research questions provide a framework for evaluating the results of the research. They help to establish the validity and reliability of the data, and provide a basis for drawing conclusions and making recommendations based on the findings of the study.

Advantages of Research Questions

There are several advantages of research questions in the research process, including:

- Focus : Research questions help to focus the research by providing a clear direction for the study. They define the specific area of investigation and provide a framework for the research design.

- Clarity : Research questions help to clarify the purpose and objectives of the study, which can make it easier for the researcher to communicate the research aims to others.

- Relevance : Research questions help to ensure that the study is relevant and meaningful. By asking relevant and important questions, the researcher can ensure that the study will contribute to the existing body of knowledge and address important issues.

- Consistency : Research questions help to ensure consistency in the research process by providing a framework for the development of the research design, data collection, and analysis.

- Measurability : Research questions help to ensure that the study is measurable by defining the specific variables and outcomes that will be measured.

- Replication : Research questions help to ensure that the study can be replicated by providing a clear and detailed description of the research aims, methods, and outcomes. This makes it easier for other researchers to replicate the study and verify the results.

Limitations of Research Questions

Limitations of Research Questions are as follows:

- Subjectivity : Research questions are often subjective and can be influenced by personal biases and perspectives of the researcher. This can lead to a limited understanding of the research problem and may affect the validity and reliability of the study.

- Inadequate scope : Research questions that are too narrow in scope may limit the breadth of the study, while questions that are too broad may make it difficult to focus on specific research objectives.

- Unanswerable questions : Some research questions may not be answerable due to the lack of available data or limitations in research methods. In such cases, the research question may need to be rephrased or modified to make it more answerable.

- Lack of clarity : Research questions that are poorly worded or ambiguous can lead to confusion and misinterpretation. This can result in incomplete or inaccurate data, which may compromise the validity of the study.

- Difficulty in measuring variables : Some research questions may involve variables that are difficult to measure or quantify, making it challenging to draw meaningful conclusions from the data.

- Lack of generalizability: Research questions that are too specific or limited in scope may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the study’s findings and restrict its broader implications.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

- Example 2

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.

- Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal , 45 (2), 209-213.

- Kyngäs, H. (2020). Qualitative research and content analysis. The application of content analysis in nursing science research , 3-11.

- Mattick, K., Johnston, J., & de la Croix, A. (2018). How to… write a good research question. The clinical teacher , 15 (2), 104-108.

- Fandino, W. (2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia , 63 (8), 611.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club , 123 (3), A12-A13

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the World of Research

Language and grammar rules for academic writing, you may also like, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , 9 steps to publish a research paper, what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures.

Literature Searching

Types of Research Questions

Research questions can be categorized into different types, depending on the type of research to be undertaken.

Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research and focus on discovering, explaining and exploring. Types of qualitative questions include:

- Exploratory Questions, which seeks to understand without influencing the results. The objective is to learn more about a topic without bias or preconceived notions.

- Predictive Questions, which seek to understand the intent or future outcome around a topic.

- Interpretive Questions, which tries to understand people’s behavior in a natural setting. The objective is to understand how a group makes sense of shared experiences with regards to various phenomena.

Quantitative questions prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis and are constructed to express the relationship between variables and whether this relationship is significant. Types of quantitative questions include:

- Descriptive questions , which are the most basic type of quantitative research question and seeks to explain the when, where, why or how something occurred.

- Comparative questions are helpful when studying groups with dependent variables where one variable is compared with another.

- Relationship-based questions try to answer whether or not one variable has an influence on another. These types of question are generally used in experimental research questions.

References/Additional Resources

Lipowski, E. E. (2008). Developing great research questions . American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 65(17), 1667–1670.

Ratan, S. K., Anand, T., & Ratan, J. (2019). Formulation of Research Question - Stepwise Approach . Journal of Indian Association of Pediatric Surgeons , 24 (1), 15–20.

Fandino W.(2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls . I ndian J Anaesth. 63(8) :611-616.

Beck, L. L. (2023). The question: types of research questions and how to develop them . In Translational Surgery: Handbook for Designing and Conducting Clinical and Translational Research (pp. 111-120). Academic Press.

Doody, O., & Bailey, M. E. (2016). Setting a research question, aim and objective. Nurse Researcher, 23(4), 19–23.

Plano Clark, V., & Badiee, M. (2010). Research questions in mixed methods research . In: SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research . SAGE Publications, Inc.,

Agee, J. (2009). Developing qualitative research questions: A reflective process . International journal of qualitative studies in education , 22 (4), 431-447.

Flemming, K., & Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Where Are We at? I nternational Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20.

Research Question Frameworks

Research question frameworks have been designed to help structure research questions and clarify the main concepts. Not every question can fit perfectly into a framework, but using even just parts of a framework can help develop a well-defined research question. The framework to use depends on the type of question to be researched. There are over 25 research question frameworks available. The University of Maryland has a nice table listing out several of these research question frameworks, along with what the acronyms mean and what types of questions/disciplines that may be used for.

The process of developing a good research question involves taking your topic and breaking each aspect of it down into its component parts.

Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Moore, G., Tunçalp, Ö., & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Formulating questions to explore complex interventions within qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ global health , 4 (Suppl 1), e001107. (See supplementary data#1)

The "Well-Built Clinical Question“: PICO(T)

One well-established framework that can be used both for refining questions and developing strategies is known as PICO(T). The PICO framework was designed primarily for questions that include interventions and comparisons, however other types of questions may also be able to follow its principles. If the PICO(T) framework does not precisely fit your question, using its principles (see alternative component suggestions) can help you to think about what you want to explore even if you do not end up with a true PICO question.

A PICO(T) question has the following components:

- P : The patient’s disorder or disease or problem of interest / research object

- I: The intervention, exposure or finding under review / Application of a theory or method

- C: A comparison intervention or control (if applicable- not always present)/ Alternative theories or methods (or, in their absence, the null hypothesis)

- O : The outcome(s) (desired or of interest) / Knowledge generation

- T : (The time factor or period)

Keep in mind that solely using a tool will not enable you to design a good question. What is required is for you to think, carefully, about exactly what you want to study and precisely what you mean by each of the things that you think you want to study.

Rzany, & Bigby, M. (n.d.). Formulating Well-Built Clinical Questions. In Evidence-based dermatology / (pp. 27–30). Blackwell Pub/BMJ Books.

Nishikawa-Pacher, A. (2022). Research questions with PICO: a universal mnemonic. Publications , 10 (3), 21.

- << Previous: Characteristics of a good research question

- Next: Choosing the Search Terms >>

How to Develop a Good Research Question? — Types & Examples

Cecilia is living through a tough situation in her research life. Figuring out where to begin, how to start her research study, and how to pose the right question for her research quest, is driving her insane. Well, questions, if not asked correctly, have a tendency to spiral us!

Image Source: https://phdcomics.com/

Questions lead everyone to answers. Research is a quest to find answers. Not the vague questions that Cecilia means to answer, but definitely more focused questions that define your research. Therefore, asking appropriate question becomes an important matter of discussion.

A well begun research process requires a strong research question. It directs the research investigation and provides a clear goal to focus on. Understanding the characteristics of comprising a good research question will generate new ideas and help you discover new methods in research.

In this article, we are aiming to help researchers understand what is a research question and how to write one with examples.

Table of Contents

What Is a Research Question?

A good research question defines your study and helps you seek an answer to your research. Moreover, a clear research question guides the research paper or thesis to define exactly what you want to find out, giving your work its objective. Learning to write a research question is the beginning to any thesis, dissertation , or research paper. Furthermore, the question addresses issues or problems which is answered through analysis and interpretation of data.

Why Is a Research Question Important?

A strong research question guides the design of a study. Moreover, it helps determine the type of research and identify specific objectives. Research questions state the specific issue you are addressing and focus on outcomes of the research for individuals to learn. Therefore, it helps break up the study into easy steps to complete the objectives and answer the initial question.

Types of Research Questions

Research questions can be categorized into different types, depending on the type of research you want to undergo. Furthermore, knowing the type of research will help a researcher determine the best type of research question to use.

1. Qualitative Research Question

Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research. However, unlike quantitative questions, qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional and more flexible. Qualitative research question focus on discovering, explaining, elucidating, and exploring.

i. Exploratory Questions

This form of question looks to understand something without influencing the results. The objective of exploratory questions is to learn more about a topic without attributing bias or preconceived notions to it.

Research Question Example: Asking how a chemical is used or perceptions around a certain topic.

ii. Predictive Questions

Predictive research questions are defined as survey questions that automatically predict the best possible response options based on text of the question. Moreover, these questions seek to understand the intent or future outcome surrounding a topic.

Research Question Example: Asking why a consumer behaves in a certain way or chooses a certain option over other.

iii. Interpretive Questions

This type of research question allows the study of people in the natural setting. The questions help understand how a group makes sense of shared experiences with regards to various phenomena. These studies gather feedback on a group’s behavior without affecting the outcome.

Research Question Example: How do you feel about AI assisting publishing process in your research?

2. Quantitative Research Question

Quantitative questions prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis through descriptions, comparisons, and relationships. These questions are beneficial when choosing a research topic or when posing follow-up questions that garner more information.

i. Descriptive Questions

It is the most basic type of quantitative research question and it seeks to explain when, where, why, or how something occurred. Moreover, they use data and statistics to describe an event or phenomenon.

Research Question Example: How many generations of genes influence a future generation?

ii. Comparative Questions

Sometimes it’s beneficial to compare one occurrence with another. Therefore, comparative questions are helpful when studying groups with dependent variables.

Example: Do men and women have comparable metabolisms?

iii. Relationship-Based Questions

This type of research question answers influence of one variable on another. Therefore, experimental studies use this type of research questions are majorly.

Example: How is drought condition affect a region’s probability for wildfires.

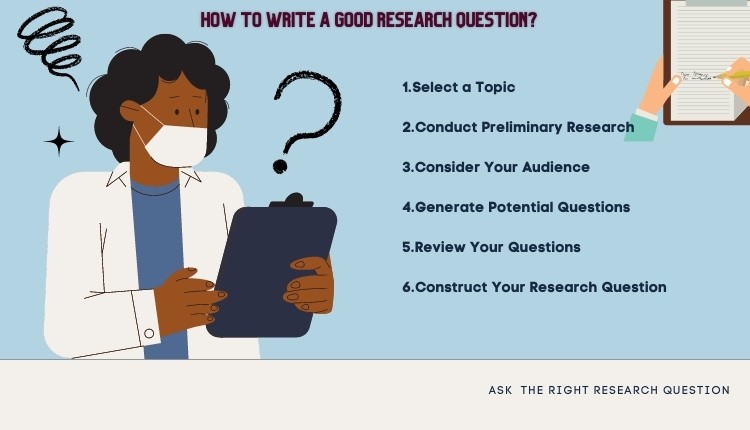

How to Write a Good Research Question?

1. Select a Topic

The first step towards writing a good research question is to choose a broad topic of research. You could choose a research topic that interests you, because the complete research will progress further from the research question. Therefore, make sure to choose a topic that you are passionate about, to make your research study more enjoyable.

2. Conduct Preliminary Research

After finalizing the topic, read and know about what research studies are conducted in the field so far. Furthermore, this will help you find articles that talk about the topics that are yet to be explored. You could explore the topics that the earlier research has not studied.

3. Consider Your Audience

The most important aspect of writing a good research question is to find out if there is audience interested to know the answer to the question you are proposing. Moreover, determining your audience will assist you in refining your research question, and focus on aspects that relate to defined groups.

4. Generate Potential Questions

The best way to generate potential questions is to ask open ended questions. Questioning broader topics will allow you to narrow down to specific questions. Identifying the gaps in literature could also give you topics to write the research question. Moreover, you could also challenge the existing assumptions or use personal experiences to redefine issues in research.

5. Review Your Questions

Once you have listed few of your questions, evaluate them to find out if they are effective research questions. Moreover while reviewing, go through the finer details of the question and its probable outcome, and find out if the question meets the research question criteria.

6. Construct Your Research Question

There are two frameworks to construct your research question. The first one being PICOT framework , which stands for:

- Population or problem

- Intervention or indicator being studied

- Comparison group

- Outcome of interest

- Time frame of the study.

The second framework is PEO , which stands for:

- Population being studied

- Exposure to preexisting conditions

- Outcome of interest.

Research Question Examples

- How might the discovery of a genetic basis for alcoholism impact triage processes in medical facilities?

- How do ecological systems respond to chronic anthropological disturbance?

- What are demographic consequences of ecological interactions?

- What roles do fungi play in wildfire recovery?

- How do feedbacks reinforce patterns of genetic divergence on the landscape?

- What educational strategies help encourage safe driving in young adults?

- What makes a grocery store easy for shoppers to navigate?

- What genetic factors predict if someone will develop hypothyroidism?

- Does contemporary evolution along the gradients of global change alter ecosystems function?

How did you write your first research question ? What were the steps you followed to create a strong research question? Do write to us or comment below.

Frequently Asked Questions

Research questions guide the focus and direction of a research study. Here are common types of research questions: 1. Qualitative research question: Qualitative questions concern broad areas or more specific areas of research. However, unlike quantitative questions, qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional and more flexible. Different types of qualitative research questions are: i. Exploratory questions ii. Predictive questions iii. Interpretive questions 2. Quantitative Research Question: Quantitative questions prove or disprove a researcher’s hypothesis through descriptions, comparisons, and relationships. These questions are beneficial when choosing a research topic or when posing follow-up questions that garner more information. Different types of quantitative research questions are: i. Descriptive questions ii. Comparative questions iii. Relationship-based questions

Qualitative research questions aim to explore the richness and depth of participants' experiences and perspectives. They should guide your research and allow for in-depth exploration of the phenomenon under investigation. After identifying the research topic and the purpose of your research: • Begin with Broad Inquiry: Start with a general research question that captures the main focus of your study. This question should be open-ended and allow for exploration. • Break Down the Main Question: Identify specific aspects or dimensions related to the main research question that you want to investigate. • Formulate Sub-questions: Create sub-questions that delve deeper into each specific aspect or dimension identified in the previous step. • Ensure Open-endedness: Make sure your research questions are open-ended and allow for varied responses and perspectives. Avoid questions that can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." Encourage participants to share their experiences, opinions, and perceptions in their own words. • Refine and Review: Review your research questions to ensure they align with your research purpose, topic, and objectives. Seek feedback from your research advisor or peers to refine and improve your research questions.

Developing research questions requires careful consideration of the research topic, objectives, and the type of study you intend to conduct. Here are the steps to help you develop effective research questions: 1. Select a Topic 2. Conduct Preliminary Research 3. Consider Your Audience 4. Generate Potential Questions 5. Review Your Questions 6. Construct Your Research Question Based on PICOT or PEO Framework

There are two frameworks to construct your research question. The first one being PICOT framework, which stands for: • Population or problem • Intervention or indicator being studied • Comparison group • Outcome of interest • Time frame of the study The second framework is PEO, which stands for: • Population being studied • Exposure to preexisting conditions • Outcome of interest

A tad helpful

Had trouble coming up with a good research question for my MSc proposal. This is very much helpful.

This is a well elaborated writing on research questions development. I found it very helpful.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Diversity and Inclusion

The Silent Struggle: Confronting gender bias in science funding

In the 1990s, Dr. Katalin Kariko’s pioneering mRNA research seemed destined for obscurity, doomed by…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Setting Rationale in Research: Cracking the code for excelling at research

Research Problem Statement — Find out how to write an impactful one!

Experimental Research Design — 6 mistakes you should never make!

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Research Questions: Definitions, Types + [Examples]

Research questions lie at the core of systematic investigation and this is because recording accurate research outcomes is tied to asking the right questions. Asking the right questions when conducting research can help you collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work, positively.

The right research questions are typically easy to understand, straight to the point, and engaging. In this article, we will share tips on how to create the right research questions and also show you how to create and administer an online questionnaire with Formplus .

What is a Research Question?

A research question is a specific inquiry which the research seeks to provide a response to. It resides at the core of systematic investigation and it helps you to clearly define a path for the research process.

A research question is usually the first step in any research project. Basically, it is the primary interrogation point of your research and it sets the pace for your work.

Typically, a research question focuses on the research, determines the methodology and hypothesis, and guides all stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. With the right research questions, you will be able to gather useful information for your investigation.

Types of Research Questions

Research questions are broadly categorized into 2; that is, qualitative research questions and quantitative research questions. Qualitative and quantitative research questions can be used independently and co-dependently in line with the overall focus and objectives of your research.

If your research aims at collecting quantifiable data , you will need to make use of quantitative research questions. On the other hand, qualitative questions help you to gather qualitative data bothering on the perceptions and observations of your research subjects.

Qualitative Research Questions

A qualitative research question is a type of systematic inquiry that aims at collecting qualitative data from research subjects. The aim of qualitative research questions is to gather non-statistical information pertaining to the experiences, observations, and perceptions of the research subjects in line with the objectives of the investigation.

Types of Qualitative Research Questions

- Ethnographic Research Questions

As the name clearly suggests, ethnographic research questions are inquiries presented in ethnographic research. Ethnographic research is a qualitative research approach that involves observing variables in their natural environments or habitats in order to arrive at objective research outcomes.

These research questions help the researcher to gather insights into the habits, dispositions, perceptions, and behaviors of research subjects as they interact in specific environments.

Ethnographic research questions can be used in education, business, medicine, and other fields of study, and they are very useful in contexts aimed at collecting in-depth and specific information that are peculiar to research variables. For instance, asking educational ethnographic research questions can help you understand how pedagogy affects classroom relations and behaviors.

This type of research question can be administered physically through one-on-one interviews, naturalism (live and work), and participant observation methods. Alternatively, the researcher can ask ethnographic research questions via online surveys and questionnaires created with Formplus.

Examples of Ethnographic Research Questions

- Why do you use this product?

- Have you noticed any side effects since you started using this drug?

- Does this product meet your needs?

- Case Studies

A case study is a qualitative research approach that involves carrying out a detailed investigation into a research subject(s) or variable(s). In the course of a case study, the researcher gathers a range of data from multiple sources of information via different data collection methods, and over a period of time.

The aim of a case study is to analyze specific issues within definite contexts and arrive at detailed research subject analyses by asking the right questions. This research method can be explanatory, descriptive , or exploratory depending on the focus of your systematic investigation or research.

An explanatory case study is one that seeks to gather information on the causes of real-life occurrences. This type of case study uses “how” and “why” questions in order to gather valid information about the causative factors of an event.

Descriptive case studies are typically used in business researches, and they aim at analyzing the impact of changing market dynamics on businesses. On the other hand, exploratory case studies aim at providing answers to “who” and “what” questions using data collection tools like interviews and questionnaires.

Some questions you can include in your case studies are:

- Why did you choose our services?

- How has this policy affected your business output?

- What benefits have you recorded since you started using our product?

An interview is a qualitative research method that involves asking respondents a series of questions in order to gather information about a research subject. Interview questions can be close-ended or open-ended , and they prompt participants to provide valid information that is useful to the research.

An interview may also be structured, semi-structured , or unstructured , and this further influences the types of questions they include. Structured interviews are made up of more close-ended questions because they aim at gathering quantitative data while unstructured interviews consist, primarily, of open-ended questions that allow the researcher to collect qualitative information from respondents.

You can conduct interview research by scheduling a physical meeting with respondents, through a telephone conversation, and via digital media and video conferencing platforms like Skype and Zoom. Alternatively, you can use Formplus surveys and questionnaires for your interview.

Examples of interview questions include:

- What challenges did you face while using our product?

- What specific needs did our product meet?

- What would you like us to improve our service delivery?

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are questions that are used to gather quantifiable data from research subjects. These types of research questions are usually more specific and direct because they aim at collecting information that can be measured; that is, statistical information.

Types of Quantitative Research Questions

- Descriptive Research Questions

Descriptive research questions are inquiries that researchers use to gather quantifiable data about the attributes and characteristics of research subjects. These types of questions primarily seek responses that reveal existing patterns in the nature of the research subjects.

It is important to note that descriptive research questions are not concerned with the causative factors of the discovered attributes and characteristics. Rather, they focus on the “what”; that is, describing the subject of the research without paying attention to the reasons for its occurrence.

Descriptive research questions are typically closed-ended because they aim at gathering definite and specific responses from research participants. Also, they can be used in customer experience surveys and market research to collect information about target markets and consumer behaviors.

Descriptive Research Question Examples

- How often do you make use of our fitness application?

- How much would you be willing to pay for this product?

- Comparative Research Questions

A comparative research question is a type of quantitative research question that is used to gather information about the differences between two or more research subjects across different variables. These types of questions help the researcher to identify distinct features that mark one research subject from the other while highlighting existing similarities.

Asking comparative research questions in market research surveys can provide insights on how your product or service matches its competitors. In addition, it can help you to identify the strengths and weaknesses of your product for a better competitive advantage.

The 5 steps involved in the framing of comparative research questions are:

- Choose your starting phrase

- Identify and name the dependent variable

- Identify the groups you are interested in

- Identify the appropriate adjoining text

- Write out the comparative research question

Comparative Research Question Samples

- What are the differences between a landline telephone and a smartphone?

- What are the differences between work-from-home and on-site operations?

- Relationship-based Research Questions

Just like the name suggests, a relationship-based research question is one that inquires into the nature of the association between two research subjects within the same demographic. These types of research questions help you to gather information pertaining to the nature of the association between two research variables.

Relationship-based research questions are also known as correlational research questions because they seek to clearly identify the link between 2 variables.

Read: Correlational Research Designs: Types, Examples & Methods

Examples of relationship-based research questions include:

- What is the relationship between purchasing power and the business site?

- What is the relationship between the work environment and workforce turnover?

Examples of a Good Research Question

Since research questions lie at the core of any systematic investigations, it is important to know how to frame a good research question. The right research questions will help you to gather the most objective responses that are useful to your systematic investigation.

A good research question is one that requires impartial responses and can be answered via existing sources of information. Also, a good research question seeks answers that actively contribute to a body of knowledge; hence, it is a question that is yet to be answered in your specific research context.

- Open-Ended Questions

An open-ended question is a type of research question that does not restrict respondents to a set of premeditated answer options. In other words, it is a question that allows the respondent to freely express his or her perceptions and feelings towards the research subject.

Examples of Open-ended Questions

- How do you deal with stress in the workplace?

- What is a typical day at work like for you?

- Close-ended Questions

A close-ended question is a type of survey question that restricts respondents to a set of predetermined answers such as multiple-choice questions . Close-ended questions typically require yes or no answers and are commonly used in quantitative research to gather numerical data from research participants.

Examples of Close-ended Questions

- Did you enjoy this event?

- How likely are you to recommend our services?

- Very Likely

- Somewhat Likely

- Likert Scale Questions

A Likert scale question is a type of close-ended question that is structured as a 3-point, 5-point, or 7-point psychometric scale . This type of question is used to measure the survey respondent’s disposition towards multiple variables and it can be unipolar or bipolar in nature.

Example of Likert Scale Questions

- How satisfied are you with our service delivery?

- Very dissatisfied

- Not satisfied

- Very satisfied

- Rating Scale Questions

A rating scale question is a type of close-ended question that seeks to associate a specific qualitative measure (rating) with the different variables in research. It is commonly used in customer experience surveys, market research surveys, employee reviews, and product evaluations.

Example of Rating Questions

- How would you rate our service delivery?

Examples of a Bad Research Question

Knowing what bad research questions are would help you avoid them in the course of your systematic investigation. These types of questions are usually unfocused and often result in research biases that can negatively impact the outcomes of your systematic investigation.

- Loaded Questions

A loaded question is a question that subtly presupposes one or more unverified assumptions about the research subject or participant. This type of question typically boxes the respondent in a corner because it suggests implicit and explicit biases that prevent objective responses.

Example of Loaded Questions

- Have you stopped smoking?

- Where did you hide the money?

- Negative Questions

A negative question is a type of question that is structured with an implicit or explicit negator. Negative questions can be misleading because they upturn the typical yes/no response order by requiring a negative answer for affirmation and an affirmative answer for negation.

Examples of Negative Questions

- Would you mind dropping by my office later today?

- Didn’t you visit last week?

- Leading Questions

A l eading question is a type of survey question that nudges the respondent towards an already-determined answer. It is highly suggestive in nature and typically consists of biases and unverified assumptions that point toward its premeditated responses.

Examples of Leading Questions

- If you enjoyed this service, would you be willing to try out our other packages?

- Our product met your needs, didn’t it?

Read More: Leading Questions: Definition, Types, and Examples

How to Use Formplus as Online Research Questionnaire Tool

With Formplus, you can create and administer your online research questionnaire easily. In the form builder, you can add different form fields to your questionnaire and edit these fields to reflect specific research questions for your systematic investigation.

Here is a step-by-step guide on how to create an online research questionnaire with Formplus:

- Sign in to your Formplus accoun t, then click on the “create new form” button in your dashboard to access the Form builder.

- In the form builder, add preferred form fields to your online research questionnaire by dragging and dropping them into the form. Add a title to your form in the title block. You can edit form fields by clicking on the “pencil” icon on the right corner of each form field.

- Save the form to access the customization section of the builder. Here, you can tweak the appearance of your online research questionnaire by adding background images, changing the form font, and adding your organization’s logo.

- Finally, copy your form link and share it with respondents. You can also use any of the multiple sharing options available.

Conclusion

The success of your research starts with framing the right questions to help you collect the most valid and objective responses. Be sure to avoid bad research questions like loaded and negative questions that can be misleading and adversely affect your research data and outcomes.

Your research questions should clearly reflect the aims and objectives of your systematic investigation while laying emphasis on specific contexts. To help you seamlessly gather responses for your research questions, you can create an online research questionnaire on Formplus.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- abstract in research papers

- bad research questions

- examples of research questions

- types of research questions

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Research Summary: What Is It & How To Write One

Introduction A research summary is a requirement during academic research and sometimes you might need to prepare a research summary...

How to Write An Abstract For Research Papers: Tips & Examples

In this article, we will share some tips for writing an effective abstract, plus samples you can learn from.

How to do a Meta Analysis: Methodology, Pros & Cons

In this article, we’ll go through the concept of meta-analysis, what it can be used for, and how you can use it to improve how you...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Popular searches

- How to Get Participants For Your Study

- How to Do Segmentation?

- Conjoint Preference Share Simulator

- MaxDiff Analysis

- Likert Scales

- Reliability & Validity

Request consultation

Do you need support in running a pricing or product study? We can help you with agile consumer research and conjoint analysis.

Looking for an online survey platform?