- Advanced Search

Version 1.1

Last updated 14 february 2019, versions 1.0, sarajevo incident.

The Sarajevo incident refers to the events surrounding the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Archduchess Sophie during a state visit to Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. It is traditionally regarded as the immediate catalyst for the First World War.

Table of Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 The Assassination

- 3 Aftermath and Consequences

Selected Bibliography

Background ↑.

The Sarajevo incident represented the culmination of a complex series of historical processes originating in Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina under the Treaty of Berlin of 1878. Over the following decades, the Dual Monarchy’s presence in the territory, still nominally under the rule of the Ottoman Sultan, brought it into conflict with various regional actors. Among these, Serbian nationalists proved the most antagonistic, perceiving Bosnia-Herzegovina’s large Serb minority as an integral part of a historic “Greater Serbia”. Moreover, by the turn of the 20 th century, the province increasingly existed at the heart of a convoluted web of rising geopolitical tensions. In 1881, Vienna had sought, and initially obtained, Germany and Russia’s approval for the future political annexation of its new Balkan protectorate. The 1894 accession of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) , however, saw St. Petersburg renege on its earlier agreements; at the regional level, Austria-Hungary’s difficulties were further exacerbated by the overthrow of Serbia’s pro-Habsburg Aleksander Obrenović, King of Serbia (1876-1903) in 1903 and the appearance of ethnic nationalism as an integral factor in Bosnian politics by 1905. The Young Turk Revolution in July 1908 subsequently served as the catalyst for direct action by the Monarchy. In October 1908, seeking to prevent the revolution from spreading northwards while reasserting political dominance over Serbia, Vienna took advantage of the political chaos within the Ottoman Empire and Russia’s diminished military capabilities, following the 1905 Russo-Japanese War , and announced that it would be formally annexing Bosnia-Herzegovina .

Despite the initial diplomatic backlash, Austria-Hungary’s reckless actions were ostensibly successful; by 1909, even Russia and Serbia had formally recognized Bosnia-Herzegovina’s transfer of sovereignty. Nevertheless, the early 1910s witnessed a continual escalation in tensions surrounding the Monarchy’s actions, coupled with rising economic and socio-political unrest within its now expanded borders. Inspired by the Bosnian Serb Bogdan Žerajić’s (1886-1910) attempted assassination of the provincial governor General Marijan Varešanin (1847-1917) in June 1910, so-called “cultural organisations”, such as “Young Bosnia” ( Mlada Bosna ), became increasingly militant.

This was compounded by the appointment of the politically ambitious General Oskar Potiorek (1853-1933) as Varešanin’s successor in 1911. The new governor’s efforts to suppress anti-Habsburg activities, following Serbia’s success during the Balkan Wars , brought Young Bosnia under the influence of the Serbian nationalist Black Hand Society. Drawing on intelligence gathered by its chief operative in Sarajevo, Danilo Ilić (1891-1915) , the society’s leaders initially proposed that Muhamed Mehmedbašić (1887-1943) , a Bosnian Muslim affiliate, attempt to assassinate Potiorek. In March 1914, however, a new target had been chosen: Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) , who would be visiting Bosnia-Herzegovina in June 1914 to observe local military manoeuvres. As the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Franz Ferdinand’s proposals for greater political autonomy within the Monarchy’s South Slav territories posed a direct challenge to Serbian nationalist ambitions. Moreover, the timing of the Archduke’s visit was perceived as a calculated snub by the provincial government since it coincided with the Serbian national and religious holiday of St. Vitus ( Vidovdan ) on 28 June.

Over the following months, Ilić recruited from among Young Bosnia’s most radical student members. Three of these youths, Nedeljko Čabrinović (1895-1916) , Trifko Grabež (1895-1916) and Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918) , who were resident in Serbia’s capital Belgrade in 1914, received money, weapons and basic training from Black Hand operatives. The trio subsequently returned to their homeland in May. According to a later testimony from Mehmedbašić, Ilić had kept the identities of the Belgrade recruits a secret until the eve of the assassination itself. Indeed, each recruit was even issued a cyanide capsule since, like Žerajić, none were expected to survive.

The Assassination ↑

Franz Ferdinand arrived in Sarajevo on 25 June 1914. Reuniting with his wife, Sophie, Archduchess of Austria (1868-1914) , the Archduke spent the following two days attending to his official duties as well as sightseeing. Princip is believed to have first observed the imperial couple as they toured the city’s famous old bazaar.

On the morning of 28 June 1914, six assassins took up positions on Appel Quey, a narrow boulevard running along the northern bank of the Miljacka River. Ilić moved between them in order to offer encouragement. Ironically, the conspirators had found an unsuspecting ally in the local authorities. Potiorek, hoping to further ingratiate himself with the Monarchy’s heir presumptive, had played down warnings of assassination plots, ignoring recent precedents such as the attempted murder of his own predecessor in 1910. Consequently, beyond a light police presence, security arrangements for the procession were notably lax. Just after 10:00 am, the Archduke’s motorcade, comprising six open-top cars, turned onto Appel Quey towards Sarajevo’s city hall. The lack of consideration afforded to security having left the vehicle in which the imperial couple travelled, with Potiorek, directly exposed to the unguarded crowds lining the street. The procession initially passed Mehmedbašić and Čubrilović, but neither reacted. Mehmedbašić later claimed that they had been deterred by the presence of a nearby police officer. As the motorcade approached the third operative, Vaso Čabrinović (1897-1990) , the would-be assassin, threw a hand grenade supplied by Ilić. Rather than landing inside, the explosive glanced off the limousine’s collapsible roof and detonated under the vehicle following behind. As the royal car accelerated away, Čabrinović swallowed his cyanide capsule and attempted to throw himself into the river. In the dry summer heat, however, it proved too shallow and the poison did little more than induce vomiting; the Young Bosnian was taken into custody, prompting his allies to disperse.

At the city hall, Potiorek, concerned over the possible damage a major security debacle might cause to his political reputation in Vienna, vetoed any suggestion of mobilizing troops, arguing that the local garrison did not possess appropriate dress uniforms. Franz Ferdinand however, insisted on visiting the hospital where those injured in the explosion had been taken for treatment. At 10:45, the motorcade departed back along Appel Quey with the imperial couple again sharing the same car as Potiorek. This decision proved fatal: the Archduke’s Czech chauffeur, Leopold Lojka (1886-1923) , was unaware of the revised schedule and, following the original procession route, turned right at the famous Latin Bridge. As Lojka attempted to reverse back out onto the thoroughfare, the car stalled in front of a popular delicatessen where Princip happened to be loitering. Drawing his pistol, the assassin fired twice, hitting the Archduke in the throat, and his wife in the abdomen; Princip would later state that Potiorek was the intended second target.

Like Čabrinović, Princip’s cyanide capsule failed to take effect, with police intervening before he could turn the gun on himself. The imperial couple were rushed to Potiorek’s official residence, however, the Archduchess was pronounced dead on arrival. By 11:00, Ferdinand had also succumbed to his injury.

Aftermath and Consequences ↑

Following the assassinations, anti-Serb demonstrations in Sarajevo, encouraged by Potiorek, quickly devolved into rioting and pogroms while the authorities moved to arrest anyone suspected of aiding the assassins. With the exception of Mehmedbašić, who managed to escape to Montenegro, Princip’s accomplices were eventually captured and tried for murder and treason. Čubrilović and Ilić were sentenced to death and executed in 1915. By contrast, under Habsburg law, Grabež, Čabrinović and Princip were still legally minors and therefore ineligible for capital punishment. All three instead received twenty-year prison terms. None would live to see the end of the First World War, with Princip being the last to die from tuberculosis in April 1918.

The assassination’s historical importance is generally attributed to it having precipitated the July Crisis . Nevertheless, even assessed in isolation from its disastrous implications, the Sarajevo incident stands as a warning on the consequences of social unrest and political alienation.

Samuel Foster, University of East Anglia

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

- Albertini, Luigi: The origins of the war of 1914 , London; New York 1952: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914 , New York 2013: Harper.

- Dedijer, Vladimir: The road to Sarajevo , New York 1966: Simon and Schuster.

- Pfeffer, Leo / Zistler, Rudolf: Istraga u Sarajevskom atentatu (Investigation into the Sarajevo assassination) , Banja Luka 2014: Besjeda.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg monarchy, 1914-1918 , Vienna 2014: Böhlau.

- Remak, Joachim: 1914. The Third Balkan War. Origins reconsidered , in: The Journal of Modern History 43/3, 1971, pp. 354-366.

Foster, Samuel: Sarajevo Incident (Version 1.1), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2019-02-14. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.11263/1.1 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A Century Ago In Sarajevo: A Plot, A Farce And A Fateful Shot

Ari Shapiro

The Latin Bridge in Sarajevo ends at the street corner where Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, on June 28, 1914. Elvis Barukcic/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

The Latin Bridge in Sarajevo ends at the street corner where Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, on June 28, 1914.

The shot that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary was fired a hundred years ago this weekend.

The assassination in Sarajevo, on June 28, 1914, triggered World War I and changed the course of the 20th century. The consequences of that act were devastating. But the beginning of the story sounds almost like a farce — complete with bad aim, botched poisoning and a wrong turn on the road.

Today, a museum marks the spot where the fateful assassination that sparked World War I occurred. Ari Shapiro/NPR hide caption

Today, a museum marks the spot where the fateful assassination that sparked World War I occurred.

Today, in the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina, you don't have to hunt around for the spot where it all took place. A big purple banner announces it in white capital letters: "The street corner that started the 20th century."

People take photos as streetcars rumble by. And according to Dr. James Lyon, an expert in Balkan history, the street would have looked almost identical a hundred years ago — it just would have had a few more trees.

A Route Lined With Flags, Fans ... And Assassins

The events of the archduke's assassination make for an unlikely story at every turn. It starts with the almost total lack of security — at the time, Sarajevo had a police force of 200.

"Approximately half or slightly less than half of the police force had turned out that day to provide security for the visit of the crown prince of the entire empire," Lyon says. "And the army was not turned out at all."

"The official reason was that the army had been out on maneuvers for the previous two days," he explains. "Their uniforms were muddy and dirty, and they were not presentable."

Also, the people in charge of the archduke's visit decided that it was a good idea to publish the motorcade route in advance. So the path was crowded with people. Bunting, flags and brightly colored carpets hung out the windows — and the would-be assassins knew exactly where to stand.

There were seven of them along the parade route, carrying bombs and guns. Most chickened out altogether.

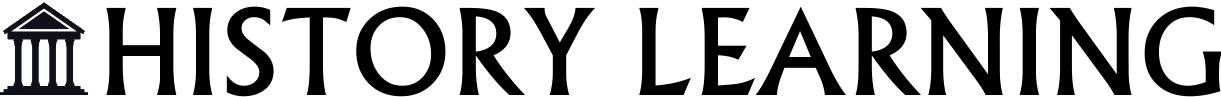

This image, captured by amateur photographer Milos Oberajge on June 28, 1914, was once believed to show Sarajevo police arresting successful assassin Gavrilo Princip. It's now thought to show the arrest of failed co-conspirator Nedeljko Cabrinovic. Topical Press Agency/Getty Images hide caption

This image, captured by amateur photographer Milos Oberajge on June 28, 1914, was once believed to show Sarajevo police arresting successful assassin Gavrilo Princip. It's now thought to show the arrest of failed co-conspirator Nedeljko Cabrinovic.

Nedeljko Cabrinovic was one exception. He threw a bomb and missed, wounding an official in the motorcade behind the archduke.

Franz Ferdinand ordered the driver to stop. He got out and walked back to inspect the damage and the wounded people.

Today, if something like that happened, the vehicles would race away from the scene as fast as they could, Lyon says. But not in 1914: "This was European nobility at the turn of the century."

Meanwhile Cabrinovic, who threw the bomb, swallowed some poison and jumped into the river below.

At that time the river would have been about 6 inches deep, 15 feet below the level of the road. Cabrinovic sprained his ankles and was unable to move.

The poison didn't work, either — it just made him sick.

The consequences of this day are hard to overstate: The events triggered a global war in which tens of millions of people died. But when you look at the assassination on its own, it seems almost farcical.

"It would be a comic tragedy of errors," Lyon says, "and it would have made for a good Peter Sellers film."

After Cabrinovic's failed assassination attempt, Franz Ferdinand gave a speech at Sarajevo's City Hall. Ari Shapiro/NPR hide caption

After Cabrinovic's failed assassination attempt, Franz Ferdinand gave a speech at Sarajevo's City Hall.

The Shot Heard Round The World

The furious archduke arrived at City Hall, where the mayor of Sarajevo delivered some totally inappropriate remarks that were written before the assassination attempt.

The archduke snapped, "What kind of welcome is this? I'm being met by bombs!" Then he wiped the blood off his prepared speech and addressed the crowd.

Afterward, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne got back into his motorcade with his wife, Sophie. They had decided to visit the hospital to see the people who were wounded in the bomb attack.

But no one told the driver.

At that fateful intersection, the car was supposed to go straight — but it turned right. A general in the motorcade shouted, "You're going the wrong way!"

And the driver stopped the car ... right in front of assassin number seven.

The Austro-Hungarian archduke and his wife, Sophie, board a car just prior to his assassination in Sarajevo. AP hide caption

The Austro-Hungarian archduke and his wife, Sophie, board a car just prior to his assassination in Sarajevo.

Gavrilo Princip, who had missed his chance the first time, was standing on the sidewalk 4 feet away from the car — at the only place on the route where the car stopped.

Princip stepped forward and fired two shots. One of them hit Sophie, and the other hit the archduke. Both shots were fatal.

As they lay dying in the car, Franz Ferdinand pleaded with his wife, "Stay alive, Sophie, for the sake of the children."

Seven Assassins — None A 007

The term "assassins" calls to mind 007 or Mission Impossible — dashing Hollywood archetypes.

But in the photos at the museum on the corner, the would-be killers hardly look dashing. They're dirty, sickly, skinny.

"Two of the seven people lying in wait were students," Lyon says. "The other five were professional revolutionaries, people who were unemployed or people who were agitating for national causes."

How Bad Directions (And A Sandwich?) Started World War I

They all seem to have had slightly different motivations — Serbian nationalists, anti-monarchists. But Lyon says they never intended to start a global war.

By the time the assassins' trial began, World War I had already broken out.

"Each and every one of them said at the trial, and later said during their imprisonment, that had they known that such a horrendous war would ensue, they would never have taken part in the activities of June 28," Lyon says.

Some of the conspirators were executed. Others died in prison. All but one are now buried just outside Sarajevo's old city, next to a highway overpass.

Earlier this week, the gravesite had one dead rose.

- Ancient Rome

- Medieval England

- Stuart England

- World War One

- World War Two

- Modern World History

- Philippines

- History Learning >

- World War One >

- Causes of World War One >

- Assassination at Sarajevo

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was the immediate cause of World War One . Europe had become a ‘powder keg’ by 1914 and the assassination was the spark that ignited these tensions.

On 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austrian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was visiting the city of Sarajevo, Bosnia’s capital.

At this point tensions in Bosnia were high. There was an increasing sense of nationalism, which was embodied in the ‘Black Hand’ movement . These nationalists wanted independence from Austria-Hungary and were willing to use terrorist tactics to achieve this goal.

The Archduke was warned that the the trip may provoke violence. Serbian nationalists viewed the visit as provocation. The visit was a way of showing off Habsburg rule and it was seen as a provocation by Serbian nationalists. But he decided to go ahead with the visit.

There had already been problems at the beginning the royal tour when a grenade his another in the entourage.

However, Franz Ferdinand wanted to continue, albeit on a route away from the city centre. However, this message was not communicated to the driver who continued through the centre.

The driver tried to reverse out onto the main streets after pausing to check where he was. The car stopped five feet from Gavrilo Princip, one of the assassins from the Black Hand. Princip shot the Archduke in the head and his wife in the abdomen. They both died shortly afterwards.

A photographer captured one of the most infamous scene from the assassination. If it wasn’t for the pre existing tensions in Europe, the assassination would never have led to war.

Serbia was blamed by Austria for this murder. Serbia was intent on liberating Bosnia from Austro-Hungarian rule and forming a unified Serbian state. Therefore, she had encouraged the actions of the Black Hand.

Austria planned to invade Serbia as punishment. Serbia called on Russia for help. Russia had a large Serbian minority and many ties with the Balkan region so and she agreed to join Serbia if Austria-Hungary attacked.

Although Serbia would have been easy for Austria to defeat, Russia was much larger and stronger. The Triple Alliance of 1882 meant that Germany had already promised to support Austria in the event of war. Germany became allied with Austria, which in turn provoked the French government.

However, decades earlier the German army had created a plan called the Schlieffen Plan . This was a strategy to allow Germany to fight a war on two fronts - in France and Russia. This plan assumed that the Russian army would take six weeks to mobilise itself. During that time, Germans could launch an attack on the French and then fight the Russians.

Germany carried out the Schlieffen Plan when France mobilised her army. They proceeded to attack France via Belgium.

At this point Britain entered the war. Britain had promised Belgium protection in 1838, so she had little choice.

Due to a combination of alliances, imperialist ambitions and rising tensions, the assassination at Sarajevo triggered the outbreak of war in August 1914.

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany after the German invasion of Belgium. France and Russia allied with Britain and Austria supported Germany.

Every country concerned was convinced that the war would be over by Christmas. Nobody could imagine the horrors of trench warfare .

See also: The Black Hand Movement

MLA Citation/Reference

"Assassination at Sarajevo". HistoryLearning.com. 2024. Web.

Related Pages

- Wilfred Owen

- World War One Poets

- Germany in 1900

- Sergeant Stubby (1916 or 1917- March 16th 1926)

- The Admiralty and the Submarine Service

- British Submarines 1900 to 1918

- British Submarines and the Baltic Sea

- Anti-submarine developments

Assassination: Sarajevo, 28 June 1914

Most readers of The Times had never heard of Sarajevo in June 1914. The assassination of a visiting Austrian royal by a Balkan nationalist fanatic therefore passed with little comment at British breakfast tables at the end of that month. Yet the two pistol shots fired into the back of a limousine by Gavrilo Princip on 28 June triggered the greatest war in history. To mark the 100th anniversary of that fateful day, MHM Editor Neil Faulkner delivers a behind-the-scenes analysis of history’s most momentous terrorist attack.

He and his wife, the Countess Sophie Chotek, were marginalised at court because of her relatively modest birth and official disapproval of their marriage; yet he lacked the charm and ease which might have enabled him to acquire friends elsewhere. Bulging in his stiff military uniform, bull-necked and with upturned handlebar moustache, he glared fixedly out of official portraits, expressionless, rigid, pickled in aristocratic hauteur.

Literature and the arts bored him; his principal occupation was hunting. The walls of his palace at Konopischt in Bohemia were hung with numerous of the 5,000 stags and 200,000 other animals he was reputed to have shot.

Eager to succeed to the imperial throne – openly impatient, indeed, at his 84-year-old uncle’s failure to die – he took his official responsibilities seriously. He ventured strong (but bigoted) opinions on the future of the decaying Austro-Hungarian Empire, making plans for its reorganisation, in particular wanting to ‘Germanise’ and centralise it by sidelining the Hungarians. He firmly opposed the military adventurism of the more hawkish elements in the government, but only because he saw the army’s primary role not as fighting foreign wars – notably, as some proposed, against the rising power of Serbia – but as the repression of ‘Jews, Freemasons, socialists, and Hungarians’ at home.

A royal visit

In late June 1914, accompanied by his wife, he travelled to the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina to observe the annual army manoeuvres. As Inspector-General of the Armed Forces, attendance at such occasions was a routine duty. But there were special reasons for coming to Bosnia just now – and for including an official visit to Sarajevo, the provincial capital, in the itinerary.

Austria-Hungary had been granted a protectorate over the province by the other European Great Powers at the Congress of Berlin in 1878 – an attempt to maintain a ‘balance of power’ in the Balkans after the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in the Russo-Turkish War. In 1908, taking advantage of Russian weakness following her defeat in the war against Japan and the turmoil of the 1905 Revolution, the Austrians had annexed the province outright.

The Austrians conceived their control of Bosnia as a check on both Russian ambition and Slav nationalism in the Balkans. The last two years had been especially worrying in this respect: the Russian-backed Kingdom of Serbia had emerged victorious and much-strengthened from the two Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, such that her beacon shone more brightly than ever as a symbol of national liberation for the oppressed Slav peoples living under Austrian rule.

The Slav menace

Of Austria-Hungary’s 50 million people, 12 million were Germans, 10 million Magyars, and almost all of the rest Slavs of one sort or another – Czechs, Poles, Little Russians, Slovaks, Slovenes, Serbs, and Croats. In Eastern Europe more widely, Germans and Magyars were massively outnumbered, for the Slavs were the ancient people of the region, a broad culture-group that had formed in the middle of the first millennium AD and then spread out to occupy most of the great land-mass framed by the Baltic, the eastern Mediterranean, the Alps, and the Urals.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Pan-Slavism had become a potent weapon in the diplomatic armoury of Russian Tsarism, and this, coupled with the recent emergence of independent national states in the Balkans, was causing deep anxiety in Vienna and Budapest. The Germans and Magyars who ruled the Austro-Hungarian Empire lived in fear of a tidal wave of insurgent nationalism: the Slavic hordes, it seemed, were shaking at the bars of what some of their leaders chose to call ‘the prison-house of nations’. The Archduke Franz Ferdinand came to Bosnia to wave a mailed fist.

The day chosen for the imperial visit to Sarajevo – 28 June – was a deliberate affront to nationalist opinion. It was the Feast of St Vitus, an occasion to remember the Turkish victory at Kosovo in 1389, which had led to the destruction of the Medieval Kingdom of Serbia. Traditionally a day of mourning, the re-emergence of an independent Serb state during the 19th century had invested the festival with new meaning: there was now much to celebrate, and much to hope for – not least in occupied Bosnia.

So Sarajevo was decked with flags when the motorcade of plume-hatted Austrians entered that morning – but they were flags for St Vitus and Kosovo, not for Franz Ferdinand.

‘Lesser breeds’

Nonetheless, security was lax: just 120 police lined the four-mile route of the official visit. ‘Do not worry,’ said one army officer in response to local police fears. ‘These lesser breeds would not dare to do anything.’

As a precaution, however, the Archduke wore seven protective amulets inside his tunic, and his wife carried a bag of holy relics: Medieval talismans as security against the revolvers and bombs of modern Balkan assassins.

Sarajevo was certainly full of enemies. Some of the crowd standing on the pavements would cheer as the motorcade went by; others would simply watch. Among those waiting without an inclination to cheer was a penniless 19-year-old Bosnian Serb student called Gavrilo Princip.

Sarajevo – this town of flags and ‘lesser breeds’ – was a microcosm of Bosnia’s complexity. Squeezed into a narrow gorge, the town was built on the banks of the River Miljacˇka, with steep wooded hills all around. There were nine bridges over the river, numerous minarets on the skyline, little houses rising up the slopes, and a labyrinthine oriental bazaar of tailors, shoemakers, leatherworkers, carpet-sellers, and coppersmiths. Street-clowns sang songs and played tambourines, and at dusk exotically veiled women offered themselves.

The town’s 50,000 inhabitants were a mixture of Orthodox Serbs, Roman Catholic Croats, Muslims, and Jews. Under the Ottoman Turks, prior to the Austrian takeover in 1878, the Muslims had formed a dominant caste. In the surrounding countryside, they often remained so, for little had changed under Austrian rule, and the mainly Christian peasants, impoverished and illiterate, still routinely paid a third of their crop each year to Muslim feudal landlords. This was the world into which Gavrilo Princip had been born.

Balkan backwardness

You had to bow your head to enter Princip’s family home in a windy mountain village in north-west Bosnia. Inside it was dark, for there were no windows, and the floor was of beaten earth. When the door was shut behind, the only light came from an open fire and from the hole in the roof through which the smoke escaped. The main room contained a wooden table, a stone bench, a water barrel, some earthenware pots and cooking utensils on a shelf, and not much else.

Such was his parents’ poverty that six of Gavrilo’s nine siblings died in infancy, and he himself contracted in childhood the tuberculosis that was destined to kill him at the age of 23. Millions lived like this in Bosnia and across the rest of south-eastern Europe.

Herein lay the deepest root of the Balkan crisis: its rural backwardness, its lack of development, its continuing stagnation in essentially Medieval conditions of life. Austria-Hungary had its Bohemian coal-mines and textile mills, its Skoda arms-works, its Viennese proletariat. Italy had the car-plants of Turin, and the banks, cinemas, and department stores of Milan. But in the Balkans, towns were few and small, factories of any size exceptional. Sarajevo had neo-classical buildings, electric trams, and a tobacco factory; but it was the bazaar that revealed its true character.

The two modern urban classes – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat – were weak throughout the Balkans; liberalism and socialism were but delicate flowers tended by a minor intelligentsia of teachers, writers, and students. The dominant politics of the region were variants of nationalism.

Slav nationalism

This is easy enough to understand. For those living under occupation, all social problems expressed themselves in foreign accents. Every form of authority – the official, the policeman, the judge, the tax-collector, even the petty-clerk – was that of an alien power. This pervasive characteristic of everyday life was experienced with special intensity by the frayed-shirt intelligentsia of young men from rural backgrounds that formed in towns like Sarajevo.

They had memories of poverty and annual tribute to absentee landlords in their villages. They had been reared on stories of legendary haiduks – traditional rural bandits who lived in defiance of authority. Now, culturally awakened by literacy and migration to an urban world of high schools and street cafés, they saw careers they might aspire to colonised by foreigners and lackeys. Nationalism came naturally to angry young men like Gavrilo Princip.

Yet Balkan nationalism was no highway to modernity: it was a twisting track leading to a precipice. The exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, who had covered the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 as a war correspondent, thought the efforts of a backward country to modernise gave it less the manner of ‘a ship that cuts its own way through the wave’ than that of ‘a barge being towed by a steamship’.

His point was that Serbia and Bulgaria in the early 20th century could not, as their leaders might have hoped, simply repeat the history of Italy and Germany in the mid 19th. The Balkan mini-states that had emerged were too small and too late-developing to be anything other than economic and political subordinates of Europe’s established Great Powers.

The Eastern Question

These states filled the space created as the decaying Ottoman Turkish Empire – which had controlled the whole of the Balkans at the start of the 19th century – succumbed to a combination of resistance from oppressed peoples and encroachments by imperial rivals.

The Serbs had achieved a degree of independence as early as 1815, a product of two peasant revolts and the patronage of Russia. The Greeks had achieved full independence by 1830, following a ten-year war in which Ottoman naval power had been destroyed by a combined British, French, and Russian fleet.

Subsequently, the Western powers had been less enthusiastic about Balkan revolution, and the British and the French had propped up ‘the sick man of Europe’ during the Crimean War of 1853-1856 as a bulwark against Russian expansion into the eastern Mediterranean. It was the great crisis of 1875-1878 that definitively transformed the Balkans into a primary focus of geopolitical conflict. Whereas the Crimean War had been engineered by the Great Powers, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 was a direct consequence of the growing dynamism of Balkan nationalism itself. The ‘Eastern Question’ acquired its own momentum – and the potential to rock the whole of Europe.

A revolt started in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1875, and quickly spread across the region, provoking genocidal Ottoman atrocities in Bulgaria, all-out war between the Ottomans and an alliance of Serbia and Montenegro, and finally a full-scale Russian invasion to protect the Tsar’s Balkan clients. Russian intervention guaranteed Ottoman defeat, but the Great Powers, desperate to contain the conflict, intervened in 1878 to impose a settlement and restore a ‘balance of power’.

The Treaty of Berlin confirmed the independence of Serbia, Montenegro, Romania, and Bulgaria, ceded some territory to Russia in the Caucasus and at the mouth of the Danube, gave Austria-Hungary a protectorate over Bosnia-Herzegovina, but left the Turks in control of the whole of the Southern Balkans except for Greece. The various Balkan rivals, some happier than others, relapsed into armed truce.

The Balkan cockpit

The settlement held, more or less, for a generation. But by the time of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s visit to Sarajevo in the summer of 1914, the region was in the throes of a second protracted crisis. The crisis had begun in 1908 with the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (an Austrian coup), had passed in 1912-1913 through two successive Balkan Wars (a Russian coup), and was now poised for a third.

The Balkan Peninsula, which was approximately the size of Germany but had only a third of the population (22 million), was divided among no less than eight states.

Turkey retained a tongue of Europe extending 250km west of Constantinople. Austria controlled Dalmatia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina in the north-west. Six independent states controlled the rest: Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Albania. Each of these had its own dynasty, army, currency, and customs system. Each contained pieces of other nationalities, and was in turn missing pieces of its own. Each was dominated sociologically by its own state apparatus, and ideologically by raucous nationalist rhetoric. These characteristics of the Balkan states were a function of economic backwardness, political fragmentation, and the self-interested interference of the Great Powers.

As the old Ottoman order collapsed, new national elites had formed around the embryonic state apparatuses themselves. Strong national identities had been forged in the risings of oppressed peoples against Ottoman rule, and these now became templates of state-formation; but in the absence of any social ballast in the form of strong urban classes, the state became over-developed to compensate for society’s under-development.

The Balkan Wars

The new mini-states then confronted one another as rivals, even as they found themselves overshadowed by the three great imperial powers jostling for advantage in the Balkan cockpit – Ottoman Turkey, Habsburg Austria, and Tsarist Russia. Large armies inspired by militant nationalism were the result. Bulgaria and Serbia both mobilised one fifth of their entire male population in the Balkan Wars, outnumbering the Turks almost two-to-one – though it was the Balkan peasant-soldier’s hatred of the Turkish oppressor that ensured victory.

But the nationalism of the oppressed had become a tool of corrupt military elites who functioned as clients of the Great Powers. The two wars of 1912-1913 revealed that Balkan nationalism had two faces.

The First Balkan War had pitted an uneasy alliance of Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro against Ottoman Turkey. The Balkan states drove the Turks out of Macedonia in the first two months of the war (October-December 1912), and then, after an abortive armistice, went on to capture the three key remaining fortresses of Adrianople, Ioannina, and Scutari (March-April 1913). The Turks held their enemies at the Chatalja Lines outside Constantinople, but Turkey-in-Europe was reduced to an enclave just 40km deep.

The Great Powers were stunned by the outcome. It revealed unsuspected Ottoman imperial weakness, equally unsuspected Balkan national strength, and had the effect of destabilising the entire European state system. The Powers united to broker a peace settlement. But it proved short-lived, for the Balkans had taken on a political life of its own.

The victors fell out, and in a Second Balkan War (June-August 1913), Bulgaria was set upon by Turkey, Romania, and her former allies Serbia and Greece. Though her armies fought valiantly, they faced attacks on all sides and were comprehensively defeated.

By the Treaties of Bucharest and Constantinople, Bulgaria was stripped of territory north and south. Turkey regained Adrianople and her territory again extended 250km into Europe. Romania took the fertile southern Dobruja, Greece most of the Aegean coast, and Serbia the well-populated Vardar valley in western Macedonia.

Petty nationalisms and mass armies

Armies of Balkan peasant-soldiers had no sooner thrown the Turk out of Macedonia than the warlords who commanded them had turned on each other in a squabble over the spoils. Thus was the manhood and treasure of the Balkans wasted by militarised mini-states whose only function was to keep the region divided, underdeveloped, and a prey of imperial sharks.

The Second Balkan War merely reset the stage for a third. Bulgaria had been the bait that momentarily absorbed the energies of predatory neighbours, allowing Turkey to recover some lost ground in alliance with former enemies. But overall, both Bulgaria and Turkey were losers, making them the potential revanchist protagonists of any future conflict. Serbia, by contrast, had made huge territorial gains at the expense of each. The battle-lines of the next war had thus been drawn – Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria against Russia, Serbia, and Romania; and the centre of gravity in the Balkans had shifted from Macedonia, cockpit of petty nationalisms in the conflicts of 1912-1913, to Serbia itself.

The socialist Tucović defined his native Serbia as a ‘bureaucratic peasant country’. It comprised a bloated bureaucracy and officer corps sustained by high levels of taxation and military conscription imposed on an overwhelmingly peasant population.

In the absence of class-based parties and any strong drive for internal reform, the factionalised politics of the elite focused on relations with Austria-Hungary. There were three broad tendencies. The most conservative faction was pro-Austrian, and had been dominant under the ruling Obrenović dynasty until 1903. In June of that year, however, a group of nationalist army officers inspired by one Dragutin Dimitrijević, alias Apis (‘the Bee’), had stormed into the palace, shot the king and queen, mutilated their bodies with sabres, and then hurled the remains out of a window.

The anti-Austrian Karadjordjević dynasty had immediately been restored to power. Apis and the extreme nationalists thereafter maintained a shadowy influence behind the constitutional screen provided by a third group, the mainstream moderate nationalists of Nikola Pašić’s Radical Party. In 1914, Apis was still a senior figure, being head of military intelligence, and Pašić had become prime minister.

The Black Hand

The Radical Party’s ascendancy was based on nationalist rhetoric, peasant votes, and opportunist practice. Its veteran leader was totally without initiative, instinctively following a policy of compromises, deals, and persistent temporising. This, explained Trotsky, who covered the Balkan Wars as a radical journalist, was the secret of Pašić’s political success, for in this way he expressed ‘a whole epoch in the development of Serbia – an epoch of weakness, manoeuvring, and abasement’.

Apis, by contrast, was a blood-and-iron nationalist, a hawkish advocate of ‘Greater Serbia’ – or ‘Yugoslavia’ – that is, a Serb-dominated union of the South Slavs such as could be constructed only through the dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

But Serbia was not Prussia (nor even Piedmont), so the extreme nationalists were obliged to pursue their schemes not through diplomacy and war, as Bismarck and Italy’s Cavour had done, but by secret conspiracies. Apis, in addition to his senior military post, was the leading figure in a terrorist network known as ‘Union or Death’ or, more commonly, ‘the Black Hand’.

This network connected senior Serbian army officers and officials – not to mention the Russian military attachés at the Belgrade consulate – with the coffee-shop society of young idealists like Gavrilo Princip.

Terrorist foot-soldiers

Princip had escaped the spiritual suffocation of a mountain village by attending secondary school in Sarajevo, where he had joined Young Bosnia, a middle-class nationalist organisation committed to ending Austrian rule. The annexation of 1908 had radicalised the young nationalists, for its implication was that without action to reverse it, Austrian rule would become permanent.

When the Metropolitan of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Sarajevo held a special service to celebrate the event, inviting ‘all the worshippers to kneel down and pray for divine blessings for the Emperor Franz Josef and the Habsburg dynasty’, everyone obliged except for a group of high-school boys that included Gavrilo Princip: his first public protest.

Later, in Belgrade, he applied to join the Serbian army, but was rejected as ‘too small and weak’. A year-and-a-half later, in the spring of 1914, he was back in Belgrade, this time applying to become an assassin. ‘I am an adherent’, he declared, ‘of the radical anarchist idea which aims at destroying the present system through terrorism.’

By 25 June, when the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife arrived outside the town, Princip was already back in Sarajevo, equipped by the Black Hand with four revolvers, six bombs, and suicide pills for himself and his six associates in case they got caught.

The annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina had been Austria’s pre-emptive strike against the corrosive effect of Serbian nationalism on the loyalty of her South Slav subjects. But it had turned educated young men from Bosnian villages into terrorists. In the absence of a mass movement to fight the poverty and oppression that enraged them, Princip and his associates were driven to the desperate methods of the weak and powerless. If the people could not – would not – liberate themselves, perhaps a dedicated group of popular champions might act on their behalf.

Four years before, also in Sarajevo, a 24-year-old Serb, Bogdan Žerajić, had fired five shots at the Austrian military governor (all misdirected) before turning his gun on himself. Žerajić was revered as a hero by Young Bosnia. Nationalist youth became devotees of the cult of the assassin, and all pledged themselves to avenge the martyr.

On the day of the Archduke’s visit to Sarajevo, the terrorists of the Black Hand distributed themselves along the central part of the Appel Quay, the main road through the town, which ran parallel with the River Miljačka – the route to be followed by the official motorcade as it passed on its way to the main reception at the Town Hall. All of them were frightened and nervous. Some were still teenagers, none had any experience handling weapons, and they were poised to carry out a cold-blooded murder and then, if necessary, commit suicide.

Mehmedbašić froze at the critical moment and never threw his bomb: there was a policeman standing in his way, he later explained. Čabrinović had to ask another policeman which was the Archduke’s car, and, on being told, primed his bomb and hurled it.

But the chauffeur saw it coming and accelerated, so it bounced off the back of the Archduke’s car and exploded under the one behind, injuring two of the occupants and a dozen or so people on the side of the road.

The front two cars of the motorcade then raced away to the Town Hall, passing the other waiting terrorists at speed, while the police arrested Čabrinović – whose cyanide capsules had merely caused him to retch – along with several other people seized in the vicinity of the attack.

Two pistol shots

The conspiracy seemed to have misfired. The authorities were now on alert, and when the Archduke’s car headed off again after the Town Hall reception, though the hood remained down, it was driven deliberately fast.

But, however amateur, the terrorists had spread themselves like a net across central Sarajevo, greatly increasing the chance that at some point their target would be ensnared. He, meantime, had decided to visit the wounded in the town hospital.

Franz Ferdinand’s chauffeur did not know Sarajevo, or perhaps had not been informed of the change of plan, and he took a wrong turning into Franz Josef Street. Called to stop and continue instead along the Appel Quay, he braked and came to a dead halt prior to backing up. A thin, pale, sunken-eyed youth standing two metres away stepped forwards, levelled a revolver, and fired two shots into the back of the car.

One bullet struck Franz Ferdinand in the neck. The other hit Sophie Chotek in the abdomen. Within 15 minutes both would be dead.

Gavrilo Princip then tried to shoot himself, but his revolver was knocked way. He next managed to swallow his cyanide capsule, but puked it up. So he was hauled away in a mêlée of police and spectators (to die of tuberculosis in an Austrian prison in April 1918).

As news of the assassination spread, a vicious anti-Serb pogrom erupted across the town. Shops, schools, and churches were vandalised. Two hundred suspects were arrested. Some were summarily hanged in the state prison. Others were murdered by sectarian lynch-mobs. A third war was beginning in the Balkans.

This time, though, it would spread to engulf the world.

This article was published in the February 2014 issue of Military History Matters . To find out more about the magazine and how to subscribe, click here .

You might be interested in

WAR CULTURE – Nevinson’s prints

MHM 91 – April 2018

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD – Calamity with a ‘K’

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Did Franz Ferdinand’s Assassination Cause World War I?

By: Annette McDermott

Updated: June 27, 2022 | Original: April 16, 2018

The causes of World War I , also known as the Great War, have been debated since it ended. Officially, Germany shouldered much of the blame for the conflict, which caused four years of unprecedented slaughter. But a series of complicated factors caused the war, including a brutal assassination that propelled Europe into the greatest conflict the continent had ever known.

The murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand outraged Austria-Hungary

In June 1914, Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie traveled to Bosnia—which had been annexed by Austria-Hungary—for a state visit.

On June 28, the couple went to the capital city of Sarajevo to inspect the imperial troops stationed there. As they headed toward their destination, they narrowly escaped death when Serbian terrorists threw a bomb at their open-topped car.

Their luck ran out later that day, however, when their driver inadvertently drove them past 19-year-old Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip who shot and killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife at point-blank range. Austria-Hungary was furious and, with Germany’s support, declared war on Serbia on July 28.

Within days, Germany declared war on Russia—Serbia’s ally—and invaded France via Belgium, which then caused Britain to declare war on Germany.

Limited industrial resources fueled the imperialist expansion

A state’s desire to expand its empire was nothing new in European history, but by the early 20th century the Industrial Revolution was in full force.

New industrial and manufacturing technologies created the need to dominate new territories and their natural resources, including oil, rubber, coal, iron and other raw materials.

With the British Empire extending to five continents and France controlling many African colonies, Germany wanted a larger slice of the territorial pie. As countries vied for position, tensions rose, and they formed alliances to position themselves for European dominance.

The rise of nationalism undermined diplomacy

During the 19th century, rising nationalism swept through Europe. As people took more pride in their country and culture, their desire to rid themselves of imperial rule increased. In some cases, however, imperialism fed nationalism as some groups claimed superiority over others.

This widespread nationalism is thought to be a general cause of World War I. For instance, after Germany dominated France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, France lost money and land to Germany, which then fueled French nationalism and a desire for revenge.

Nationalism played a specific role in World War I when Archduke Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated by Princip, a member of a Serbian nationalist terrorist group fighting against Austria-Hungary’s rule over Bosnia.

Entangled alliances created two competing groups

In 1879, Germany and Austria-Hungary allied against Russia. In 1882, Italy joined their alliance (The Triple Alliance) and Russia responded in 1894 by allying with France.

In 1907, Great Britain, Russia and France formed the Triple Entente to protect themselves against Germany’s growing threat. Soon, Europe was divided into two groups: The Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy; and the Allies, which included Russia, France and Britain.

As war was declared, the allied countries emboldened each other to enter the fray and defend their treaties, although not every coalition was set in stone—Italy later changed sides. By the end of August 1914, the so-called “entangled alliances” had caused what should have been a regional conflict to expand to all of Europe’s powerful states.

Militarism sparked an arms race

In the early 1900s, many European countries increased their military might and were ready and willing put it to use. Most of the European powers had a military draft system and were in an arms race, methodically increasing their war chests and fine-tuning their defense strategies.

Between 1910 and 1914, France, Russia, Britain and Germany significantly increased their defense budgets. But Germany was by far the most militaristic country in Europe at the time. By July 1914, it had increased its military budget by a massive 79 percent.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

Germany was also in an unofficial war with Britain for naval superiority. They doubled their naval battle fleet as Britain’s Royal Navy produced the first Dreadnought battleship which could outgun and outrun any other battleship in existence. Not to be outdone, Germany built its own fleet of Dreadnoughts.

By the start of World War I, the European powers were not just prepared for war, they expected it and some even counted on it to increase their world standing.

Although the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand was the spark that caused Austria-Hungary to strike the first blow, all the European powers quickly fell in line to defend their alliances, preserve or expand their empires and display their military might and patriotism.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Almost “nothing”: why did the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand lead to war?

Misfire: The Sarajevo Assassination and the Winding Road to World War I

- By Paul Miller-Melamed

- June 24 th 2022

Shot through the neck, choking on his own blood with his beloved wife dying beside him, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, managed a few words before losing consciousness: “It’s nothing,” he repeatedly said of his fatal wound. It was 28 June 1914, in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. One month later, what most Europeans also took for “nothing” became “something” when the Archduke’s uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph, declared war on Serbia for allegedly harboring the criminal elements and tolerating the propaganda that prompted the assassination. The First World War began not with Gavrilo Princip’s pistols shots, but because European statesmen were unable to resolve the July [diplomatic] Crisis that ensued.

That crisis may have been short-lived, but the conflict between the venerable Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary) and the upstart (and far smaller) kingdom of Serbia had been brewing for decades. At its core were the South Slavs of Bosnia-Herzegovina—Muslims, Catholic Croats, and, above all, Orthodox Serbs that Serbia claimed as its rightful irredenta, its “unredeemed” peoples. Austria-Hungary had administered Bosnia since taking over from the declining Ottoman Empire in 1878. It poured enormous resources into developing the territory economically, though scant benefits were seen by peasants like Princip’s family, who resented their poverty and repression under Austrian rule as much as they had the Ottomans’ long reign. Then, in 1908, the Habsburg Empire annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina outright. For the next six months, the Bosnian [annexation] Crisis convulsed Europe. It has been called the prelude to World War I, though it by no means made that war “inevitable.” Russia, which sought control over the central Balkan region possibly through its partner state Serbia, was too weak to fight back in the wake of its defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. And while the Serbs were, literally, up in arms and made a big show of mobilizing their meager army, they stood no chance without Russian backing. Meanwhile, the annexation was accepted by the other Great Powers as a fait accompli.

It would be easy to conclude from this sparse summary of Balkan tensions that the Sarajevo assassination was driven by Serbian resentment over Austrian control of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Such an interpretation is strengthened by the fact that myriad accounts of the political murder depict Princip and his accomplices as “Serbs” or “Serb nationalists” backed by a “secret” Serbian “terrorist” organization: Unification or Death, more notoriously known as the Black Hand. It’s all very subversive and satisfying to our contemporary sensibilities. Some scholars have thus even latched onto analogies between the Black Hand “terrorist network” and today’s Islamic fundamentalists. The issue is not merely inaccuracy or exaggeration, but that it’s part of the mythology that has accumulated around the Sarajevo assassination.

It’s true that the assassins concocted their plot in Belgrade and obtained their weapons, training, and logistical support in Serbia. Yet no official Serbian organization sponsored them, and there’s no evidence that anyone but rogue rebels in the Black Hand acted to aid the Bosnians, rather than the highly nationalist military faction itself. Far closer to the truth is that Princip and his co-Bosnian conspirators needed no more motivation to organize and execute the assassination than their patent suffering under Habsburg rule, as they insisted repeatedly at their trial. Serbia, meanwhile, did not need a war with a European Great Power, particularly on the heels of its hard-fought victories in the Balkan Wars (1912/1913). The Black Hand leaders knew this, which is why there’s evidence that they actually tried to stop the conspiracy that they never initiated in the first place. Yet the demonization of official Serbia and its uncontrollable nationalist factions persists as the main explanation for the Sarajevo assassination.

This should not be surprising, and not because the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s put Serbian nationalism again on display. No, the reason the alleged Serbian backing of the Sarajevo assassination is so compelling is the war itself—for how to explain the Sarajevo assassination has become an escape hatch for the true criminals in Europe’s “civilized” capitals. Thus, the myth of Sarajevo includes the endless stereotypes of the “savage” and “war-prone” Balkan peoples, “fanatic” Serb nationalists, “terminally ill” (with tuberculosis) assassins, and that ubiquitous explanation for everything—Europe’s “fate” and Princip’s “chance.” After all, who has not heard of the “wrong turn” taken by the heir’s car after he narrowly escaped a bomb attack that very morning; or wondered why the imperial procession had even continued after the near miss; or pondered how Princip’s first bullet happened to kill the one person he wished to spare: Franz Ferdinand’s wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg? There was so much happenstance on that “cloudless” Sunday of Europe’s over idealized “last summer” that it is all too easy to forget that the initial decision for war with Serbia was taken in Vienna, not Sarajevo, and it was made with full knowledge of possible Russian intervention and, thus, European war.

The Sarajevo assassination did not “shock” the world. Nor was it a “flashbulb event” that imprinted itself on the minds and memories of all contemporaries. On the contrary, countless first-hand accounts support the relative apathy and indifference that greeted the murder—a tragedy, certainly, but not one which, as British undersecretary of state Sir Arthur Nicolson wrote eerily to his ambassador in St. Petersburg, would “lead to further complications.” What “changed everything” was not a Bosnian assassin’s poorly aimed bullets, but the historical misfire by Europe’s Great Powers, which first came to light with Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July 1914. By then, the Sarajevo assassination was slipping from memory—this was an age, after all, in which political murder was all too common; or, as one American newspaper casually put it, there were other Austrian heirs to replace the Archduke. But Austria-Hungary had had enough of Serbian irredentism, despite the fact that its investigators found no evidence whatsoever of Belgrade’s collusion in the Sarajevo conspiracy. And Franz Ferdinand’s final words about his fatal wound—“it’s nothing”—would never seem more ironic than when the “first shots of the First World War” were fired—not in the Bosnian capital on 28 June 1914, as myth has it, but by Austrian gunboats against Belgrade a full month later.

Featured image: from Washington Examiner, via Wikimedia Commons , public domain

Paul Miller-Melamed teaches history at the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin in Poland and McDaniel College in the United States. He is the author of From Revolutionaries to Citizens: Antimilitarism in France, 1870-1914 and the co-editor of Embers of Empire: Continuity and Rupture in the Habsburg Successor States after 1914. His most recent book Misfire: The Sarajevo Assassination and the Winding Road to World War I is now available from Oxford University Press.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

No related posts.

Recent Comments

I’m looking forward to reading this book. It clearly seeks to separate fact from fiction, and so I expect it to take a favourable view of the recent discoveries until now only outlined in the seminal work on this ww1 subject, ‘Folly and Malice’ by John Zametica

Maybe the entire fiasco should have been left as an essentially small event between the initial parties rather than letting a system of alliances lead to a major conflict which killed tens of millions of people who had nothing to do with it at all. And Wilson’s prolongation, well, no comment.

Something attributed to Napoleon – history is a later event, a fable agreed upon by the victors.

Comments are closed.

The Sarajevo Assassination That Didn’t Happen

The Ironic Relevance of a "Nonevent"

Paul Miller-Melamed | Sep 14, 2022

O n the blustery afternoon of May 31, 1910, Habsburg emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary peacefully paraded by horse-drawn carriage through the crowded streets of Bosnia’s capital city, Sarajevo. Barely a year earlier, the Bosnian annexation crisis had nearly sparked a European war. Although the Habsburg monarchy had administered Bosnia-Herzegovina since 1878, the Kingdom of Serbia coveted the adjacent, south Slavic region as its rightful irredenta, and Russia backed Belgrade’s national ambitions in the contested Balkans. Franz Joseph’s visit was thus a political affront and a perilous act. Yet no bombs were hurled at him by Bosnian or Serb nationalists, no bullets fired at his regal presence in the empire’s newly annexed province of Bosnia-Herzegovina. By all accounts, the 79-year-old emperor of Austria and king of Hungary so thoroughly enjoyed himself in his southernmost Slavic domains that, at one point, he turned to his host, Bosnian governor-general Marijan Varešanin, and exulted: “I assure you, this voyage has made me some 20 years younger!”

.jpg)

Emperor Franz Joseph processing through Sarajevo on May 31, 1910, the day of the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen. Courtesy Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Call no. Pk 1372, 8a

In fact, it nearly ended his life more than six years prematurely. Although security was far heavier than it would be when Franz Joseph’s nephew and successor, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, made his infinitely more infamous visit to Bosnia and procession through Sarajevo four years later, an armed nationalist named Bogdan Žerajić had twice gotten so close to the kaiser that, as he despairingly told a friend, “I could have practically touched him.” Yet out of some combination of fear and fecklessness, the Bosnian student never pulled the Browning pistol from his pocket. It was the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen. It was just one of several attempts on the kaiser’s life that failed to materialize or just failed altogether. It was, one might say, a nonevent.

The term nonevent can be understood in two ways: the obvious sense of something that simply did not happen and the more commonplace usage of an anticlimactic occurrence. In the latter case, like a highly anticipated diplomatic summit in which nothing serious gets resolved, a nonevent may be an actual event that’s less exciting, or “historic,” than expected. This can also work in reverse: our instinctive need for decisive moments in history to be appropriately “eventful” often affects how we remember them. Mussolini’s 1922 “march on Rome,” where Il Duce arrived by train to tranquilly receive the king’s consent to form a government, only became a dramatic “event” through later fascist propaganda. Many of history’s seemingly heroic episodes, like the Bolsheviks’ “storming” of the Winter Palace (or, more accurately, its wine cellar), have similar lineages. What makes Žerajić’s inescapably unheroic attempt on the kaiser’s life unusual for a nonevent is that it bridges both these definitions: it didn’t happen (i.e., he never drew his revolver, let alone drew attention to himself as a suspect assassin) and later memory made it more than it ever was. Indeed, Žerajić’s failure to fire would become a nonevent of such great pitch and moment that it inspired one of the signal events of the 20th century—the Sarajevo assassination.

As every European history textbook teaches, on June 28, 1914, a young Bosnian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Habsburg Empire, in Sarajevo. This event, this Sarajevo assassination as we know it, sparked a diplomatic crisis that only resolved itself in the First World War. Yet Princip probably never even would have had a chance if not for Žerajić’s inaction, his nonevent. Would “Emperor” Franz Ferdinand have risked going to Sarajevo in 1914 if his predecessor had been murdered there in 1910? If he did, security arrangements would have been extreme to say the least.

Our instinctive need for decisive moments in history to be appropriately “eventful” often affects how we remember them.

The problem with such hypotheticals is that they are simply endless, and in the end no more useful, or fruitful, than the already existing scholarly contemplations on what if Princip had misfired and Franz Ferdinand, like his uncle before him, had returned to Vienna alive. Everything that occurred between 1910 and 1914 would have been different with Franz Ferdinand on the throne, as he may have faced world war in 1910, or fostered an alliance with his “best friend,” Russia, or intervened against Serbia during the Balkan Wars in 1912–13. And why belabor Bogdan Žerajić’s specific nonevent when the archduke’s actual assassination barely came off?

After all, Franz Ferdinand had received numerous warnings against going to Bosnia in the first place. Assassination attempts were rife in the region, and Habsburg authorities had eventually found out about Žerajić’s bungled one. They passed their intelligence on to the archduke, though this nonevent by no means stood out from all the other intrigues the heir was briefed on regularly. Even on the eve of the Sarajevo procession, Franz Ferdinand was forcefully warned by Bosnian officials and men in his own entourage about the dangers of driving through the capital in an open air car on a Serb national holiday (Vidovdan, or St. Vitus Day). Yet it was less his well-known stubbornness than an honorable sense of imperial service that led him to go through with the Sarajevo program in the first place. “Fears and precautions paralyze your life,” the archduke once told a legal adviser, adding that he would rather put his trust in God than live “in a bell jar” worrying over the next nationalist assassin. Franz Ferdinand’s fatalism in ignoring the warnings was less insane than it seems to us today, since “the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen” is just one of a limitless litany of nonevents that assured the archduke to risk the one that did.

But even with the stage set, it was far from a sure thing. Who has not heard of the “wrong turn” taken by the heir’s car after he narrowly escaped a bomb attack that very morning; or wondered why the imperial procession had even continued after the near miss; or pondered how Princip’s first bullet happened to kill the one person the assassin wished to spare: Franz Ferdinand’s wife, Sophie Chotek, the duchess of Hohenberg? There certainly was enough drama on June 28, 1914, to safely ignore the nonevent on May 31, 1910.

God, clearly, was not on the successor’s side on June 28, 1914. Nevertheless, much happened that day that harked back to May 31, 1910, like the little-known fact that five of the seven so-called assassins backed out of the mission in the midst of the procession, and that its organizer tried to call off the intrigue even as he was distributing the weapons. So the question persists: Why dwell on “the Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen,” besides the obvious attraction of historical symmetry? Truly, there seems little more reason to highlight Žerajić’s inaction in the Bosnian capital in 1910 than such nonevents as the archduke’s near death from tuberculosis in the 1890s; his witnessing of the failed attempt against Spanish king Alfonso XIII during the latter’s May 1906 wedding in Madrid (which left 23 people dead); and the 1913 arrest in Zagreb of one Luka-Lujo Aljionvić for plotting to kill the crown prince—“this rubbish who is restraining our national aspirations.” What there is more of, however, is “actual” history itself.

His final shot was precise, shattering his own skull and making him a martyr.

Žerajić, in short, was not finished, and this is the reason anyone knows about his futile attempt in the first place. Two weeks after losing his opportunity to eliminate the emperor, the 24-year-old fired five near misses at Governor-General Varešanin as he was leaving the newly inaugurated parliament in Sarajevo. His final shot was precise, shattering his own skull and making him a martyr figure for Bosnian freedom from Habsburg rule. The failed assassin of Emperor Franz Joseph had now done something for his country’s freedom that no Bosnian had dared before. The tributes, predictably, were fast and forthcoming—within days of Žerajić’s “heroic” historic event, young Bosnians were doffing their hats at the site of his suicide. The Serbian student review Zora ( Dawn ) reverently kept the would-be assassin’s name on its masthead. Although Sarajevo police furtively buried Žerajić in the vagrants’ cemetery, the site was readily discovered and regularly decorated by Bosnian youth. Free Serbia’s leading daily sang Žerajić’s praises wildly. Yet no one did more for Žerajić’s memory than his school friend and fervent Serb nationalist Vladimir Gaćinović. In February 1912, Gaćinović published the pamphlet Death of a Hero in a Belgrade-based Serbian nationalist journal. Scripted literally to “spark revolution in the souls and minds of young Serbs,” Death of a Hero bemoaned the absence of “grand, noble gestures” in Bosnia since Žerajić’s attempt. Where, he beseeched, were all those virtuous “men of action”? Who, he wondered, would take up the assassin-suicide’s selfless legacy?

Gavrilo Princip heeded the call. He had often made the pilgrimage to Žerajić’s grave site, on which he placed a handful of the “earth of free Serbia.” On the evening before murdering Franz Ferdinand, he headed there again to pay final tribute to his martyred hero. And in yet another confounding and contingent nonevent, such obvious warning signs were ignored. The Austro-Hungarian authorities who had informed Franz Ferdinand of Žerajić’s attempt on the emperor neglected to stake out the familiar pilgrimage site and detain Princip until the archduke had departed Bosnia. Consequently, on June 28, 1914, the little-known Sarajevo assassination that didn’t happen came full circle with the legendary one that did. “Glory to Žerajić!” proclaimed Princip at his trial. A nonevent in 1910 had suddenly ascended to a highly relevant, indeed world historical, event four years later. It was an irony and tragedy that would devastate humanity.

Paul Miller-Melamed is associate professor of history emeritus at McDaniel College and adjunct professor at the Catholic University of Lublin and Quinnipiac University. He is the author of Misfire: The Sarajevo Assassination and the Winding Road to World War I (Oxford Univ. Press, 2022).

Tags: Features Europe Social History

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities , and in letters to the editor . Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

Related Content

Yoav Tenembaum | May 1, 2015

Leila Fawaz | Nov 16, 2015

Mark Grimsley | May 1, 2015

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Collections

- All collections & departments

- Germanic collections

- About the collections

- Spotlight archive

- Cambridge University Library

- Using the Library overview

- Your library membership overview

- Online resources and services

- Zero contact services overview

- Visit the University Library overview

- Library Service Updates

- Accessibility and disabled library users overview

- Research overview

- University Library Research Institute overview

- Digital Preservation overview

- Digital Humanities overview

- Open Access

- Office of Scholarly Communication

- Research Data Management

- Futurelib Innovation Programme overview

- Teaching and Learning overview

- Information Literacy Teaching at Cambridge

- What's On overview

- Exhibitions overview

- Events overview

- The Really Popular Book Club

- Friends Events

- Annual Lectures overview

- Google Arts and Culture

- Search and Find overview

- LibGuides - Subject guides

- eResources overview

- ArchiveSearch

- Reference Management overview

- Physical catalogues overview

- Collaborative catalogues

- Collections overview

- Physical Collections

- Online Collections

- Special Collections overview

- All collections & departments overview

- Journals Co-ordination Scheme overview

- Recommend an item for our collection overview

- The Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project

- About overview

- Governance overview

- History of the Library overview

- Diversifying Collections and Practices overview

- Statement on the University’s Historical Involvement with Tobias Rustat

- Prizes and Fellowships overview

- Library Storage Facility

- Press and media

- Giving overview

- Friends of the Library overview

- Make a Donation overview

- Philanthropy

- Sarajevo 1914

- All collections & departments

- Operation Valkyrie 1944

- Burning Books

- Bicentenary of the birth of Georg Büchner

- The 1936 Berlin Olympic Games

- German prizewinners 2012

- Talk on German Collections

- DigiZeitschriften

- German prizewinners 2011

- The death of King Ludwig II

- Switzerland and Pro Helvetia

- Donation of Fritz Möser linoprints

- Donation of cinema books

- Collection policy

- Classification

- Recommendations for acquisition

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on June 28th 1914 will forever be remembered as one of the key turning points in twentieth century world history. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie were shot dead in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Black Hand gang, a group of Serbian nationalists, whose aim was to free Serbia of the rule of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The assassination of its heir presumptive gave Austria-Hungary the opportunity to settle some old scores and declare war on Serbia, which, in turn, precipitated a political crisis between the major European powers, and this, in turn, triggered a chain of events which led directly to the outbreak of the First World War. This feature will commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Sarajevo assassination and explore how the event and its consequences are represented in the UL’s German collections.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria (source)

From an early age, Franz Ferdinand pursued a military career in the Austro-Hungarian army and became heir to the Habsburg throne following the suicide of his cousin Crown Prince Rudolf at the famous hunting lodge in Mayerling in 1889. There was tension in his relationship with Emperor Franz Joseph, but historians have differed regarding the nature of Franz Ferdinand’s political views. Some historians emphasise his liberalism compared to the emperor, especially his advocacy of greater autonomy for ethnic groups within the Austro-Hungarian empire, whilst others emphasise his Catholic conservatism and absolutist belief in Austro-Hungarian dynastic rule.

The biographical aspects of Franz Ferdinand’s life are explored in “Alma Hannig : Franz Ferdinand, die Biografie (2013)” at 607:4.c.201.6 and “Max Polatschek : Franz Ferdinand, Europas verlorene Hoffnung (1989)” at 607:45.c.95.39 . The UL will be acquiring the latest three volume work on Franz Ferdinand’s life: “Wladimir Aichelburg : Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este 1863-1914 : Notizen zu einem ungewöhnlichen Tagebuch eines aussergewöhnlichen Lebens : Europas Weg zur Apokalypse (2014)”. There is also currently an exhibition of Franz Ferdinand’s travels entitled “Franz is here” at the Weltmuseum in Vienna and the UL will shortly be acquiring the catalogue of this exhibition.

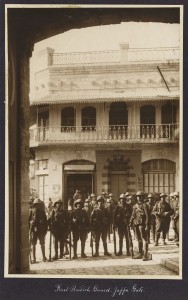

Sarajevo Town Hall, a few minutes before the assassination (source)