- Privacy Policy

Home » Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Table of Contents

Survey Research

Definition:

Survey Research is a quantitative research method that involves collecting standardized data from a sample of individuals or groups through the use of structured questionnaires or interviews. The data collected is then analyzed statistically to identify patterns and relationships between variables, and to draw conclusions about the population being studied.

Survey research can be used to answer a variety of questions, including:

- What are people’s opinions about a certain topic?

- What are people’s experiences with a certain product or service?

- What are people’s beliefs about a certain issue?

Survey Research Methods

Survey Research Methods are as follows:

- Telephone surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents over the phone, often used in market research or political polling.

- Face-to-face surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents in person, often used in social or health research.

- Mail surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through mail, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Online surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through online platforms, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Email surveys: A survey research method where questionnaires are sent to respondents through email, often used in customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-mode surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, often used to increase response rates or reach diverse populations.

- Computer-assisted surveys: A survey research method that uses computer technology to administer or collect survey data, often used in large-scale surveys or data collection.

- Interactive voice response surveys: A survey research method where respondents answer questions through a touch-tone telephone system, often used in automated customer satisfaction or opinion surveys.

- Mobile surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through mobile devices, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Group-administered surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to a group of respondents simultaneously, often used in education or training evaluation.

- Web-intercept surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to website visitors, often used in website or user experience research.

- In-app surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to users of a mobile application, often used in mobile app or user experience research.

- Social media surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through social media platforms, often used in social media or brand awareness research.

- SMS surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through text messaging, often used in customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- IVR surveys: A survey research method where questions are administered to respondents through an interactive voice response system, often used in automated customer feedback or opinion surveys.

- Mixed-method surveys: A survey research method that combines both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods, often used in exploratory or mixed-method research.

- Drop-off surveys: A survey research method where respondents are provided with a survey questionnaire and asked to return it at a later time or through a designated drop-off location.

- Intercept surveys: A survey research method where respondents are approached in public places and asked to participate in a survey, often used in market research or customer feedback.

- Hybrid surveys: A survey research method that combines two or more survey modes, data sources, or research methods, often used in complex or multi-dimensional research questions.

Types of Survey Research

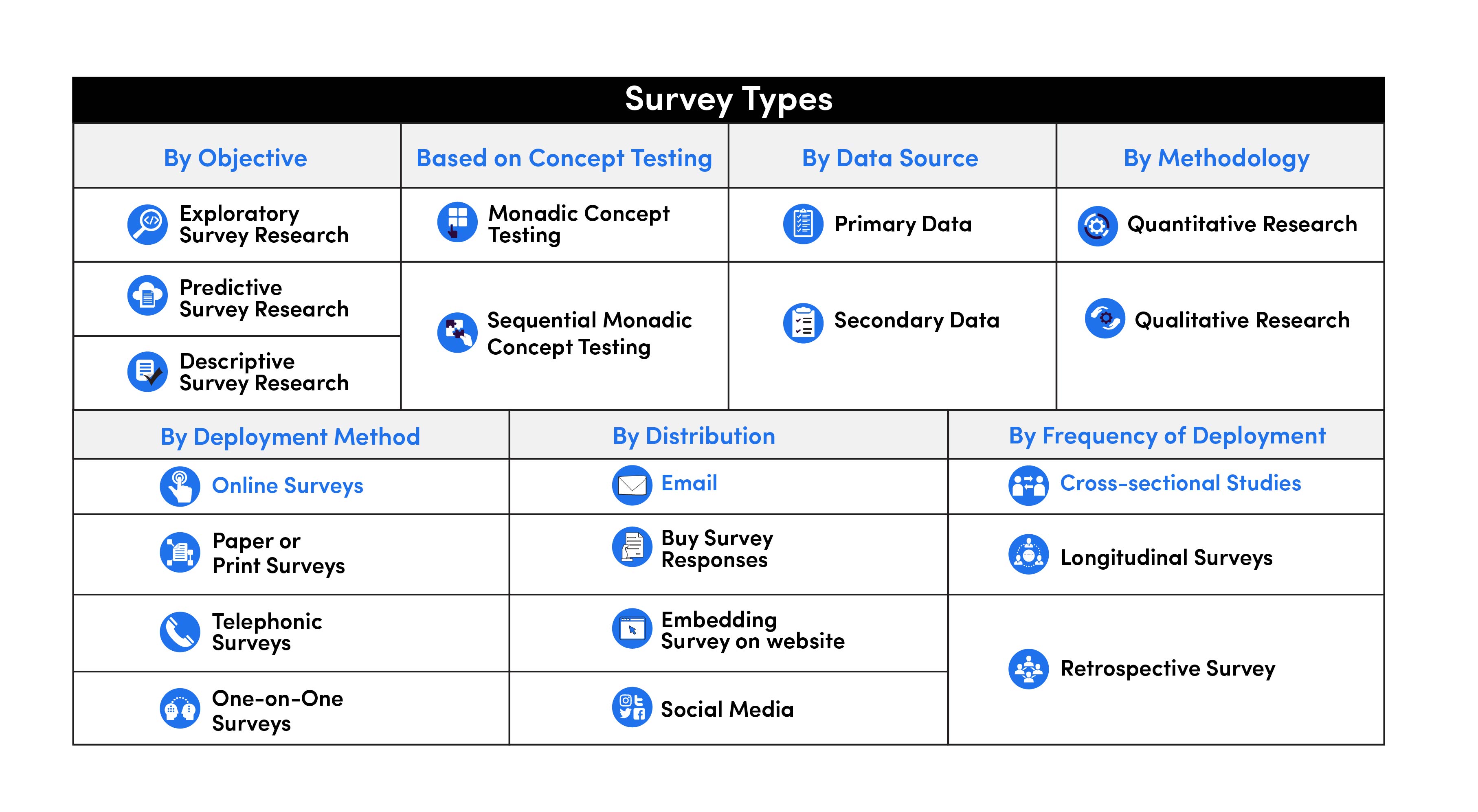

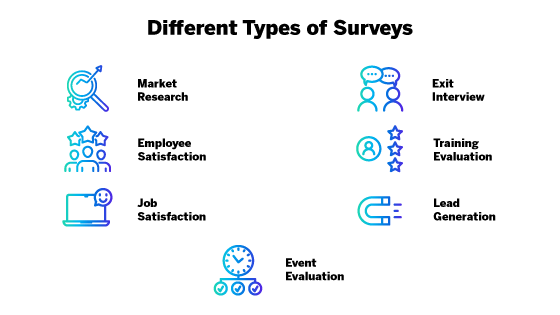

There are several types of survey research that can be used to collect data from a sample of individuals or groups. following are Types of Survey Research:

- Cross-sectional survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from a sample of individuals at a specific point in time, providing a snapshot of the population being studied.

- Longitudinal survey: A type of survey research that gathers data from the same sample of individuals over an extended period of time, allowing researchers to track changes or trends in the population being studied.

- Panel survey: A type of longitudinal survey research that tracks the same sample of individuals over time, typically collecting data at multiple points in time.

- Epidemiological survey: A type of survey research that studies the distribution and determinants of health and disease in a population, often used to identify risk factors and inform public health interventions.

- Observational survey: A type of survey research that collects data through direct observation of individuals or groups, often used in behavioral or social research.

- Correlational survey: A type of survey research that measures the degree of association or relationship between two or more variables, often used to identify patterns or trends in data.

- Experimental survey: A type of survey research that involves manipulating one or more variables to observe the effect on an outcome, often used to test causal hypotheses.

- Descriptive survey: A type of survey research that describes the characteristics or attributes of a population or phenomenon, often used in exploratory research or to summarize existing data.

- Diagnostic survey: A type of survey research that assesses the current state or condition of an individual or system, often used in health or organizational research.

- Explanatory survey: A type of survey research that seeks to explain or understand the causes or mechanisms behind a phenomenon, often used in social or psychological research.

- Process evaluation survey: A type of survey research that measures the implementation and outcomes of a program or intervention, often used in program evaluation or quality improvement.

- Impact evaluation survey: A type of survey research that assesses the effectiveness or impact of a program or intervention, often used to inform policy or decision-making.

- Customer satisfaction survey: A type of survey research that measures the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of customers with a product, service, or experience, often used in marketing or customer service research.

- Market research survey: A type of survey research that collects data on consumer preferences, behaviors, or attitudes, often used in market research or product development.

- Public opinion survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or social research.

- Behavioral survey: A type of survey research that measures actual behavior or actions of individuals, often used in health or social research.

- Attitude survey: A type of survey research that measures the attitudes, beliefs, or opinions of individuals, often used in social or psychological research.

- Opinion poll: A type of survey research that measures the opinions or preferences of a population on a specific issue or topic, often used in political or media research.

- Ad hoc survey: A type of survey research that is conducted for a specific purpose or research question, often used in exploratory research or to answer a specific research question.

Types Based on Methodology

Based on Methodology Survey are divided into two Types:

Quantitative Survey Research

Qualitative survey research.

Quantitative survey research is a method of collecting numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of standardized surveys or questionnaires. The purpose of quantitative survey research is to gather empirical evidence that can be analyzed statistically to draw conclusions about a particular population or phenomenon.

In quantitative survey research, the questions are structured and pre-determined, often utilizing closed-ended questions, where participants are given a limited set of response options to choose from. This approach allows for efficient data collection and analysis, as well as the ability to generalize the findings to a larger population.

Quantitative survey research is often used in market research, social sciences, public health, and other fields where numerical data is needed to make informed decisions and recommendations.

Qualitative survey research is a method of collecting non-numerical data from a sample of participants through the use of open-ended questions or semi-structured interviews. The purpose of qualitative survey research is to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences, perceptions, and attitudes of participants towards a particular phenomenon or topic.

In qualitative survey research, the questions are open-ended, allowing participants to share their thoughts and experiences in their own words. This approach allows for a rich and nuanced understanding of the topic being studied, and can provide insights that are difficult to capture through quantitative methods alone.

Qualitative survey research is often used in social sciences, education, psychology, and other fields where a deeper understanding of human experiences and perceptions is needed to inform policy, practice, or theory.

Data Analysis Methods

There are several Survey Research Data Analysis Methods that researchers may use, including:

- Descriptive statistics: This method is used to summarize and describe the basic features of the survey data, such as the mean, median, mode, and standard deviation. These statistics can help researchers understand the distribution of responses and identify any trends or patterns.

- Inferential statistics: This method is used to make inferences about the larger population based on the data collected in the survey. Common inferential statistical methods include hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and correlation analysis.

- Factor analysis: This method is used to identify underlying factors or dimensions in the survey data. This can help researchers simplify the data and identify patterns and relationships that may not be immediately apparent.

- Cluster analysis: This method is used to group similar respondents together based on their survey responses. This can help researchers identify subgroups within the larger population and understand how different groups may differ in their attitudes, behaviors, or preferences.

- Structural equation modeling: This method is used to test complex relationships between variables in the survey data. It can help researchers understand how different variables may be related to one another and how they may influence one another.

- Content analysis: This method is used to analyze open-ended responses in the survey data. Researchers may use software to identify themes or categories in the responses, or they may manually review and code the responses.

- Text mining: This method is used to analyze text-based survey data, such as responses to open-ended questions. Researchers may use software to identify patterns and themes in the text, or they may manually review and code the text.

Applications of Survey Research

Here are some common applications of survey research:

- Market Research: Companies use survey research to gather insights about customer needs, preferences, and behavior. These insights are used to create marketing strategies and develop new products.

- Public Opinion Research: Governments and political parties use survey research to understand public opinion on various issues. This information is used to develop policies and make decisions.

- Social Research: Survey research is used in social research to study social trends, attitudes, and behavior. Researchers use survey data to explore topics such as education, health, and social inequality.

- Academic Research: Survey research is used in academic research to study various phenomena. Researchers use survey data to test theories, explore relationships between variables, and draw conclusions.

- Customer Satisfaction Research: Companies use survey research to gather information about customer satisfaction with their products and services. This information is used to improve customer experience and retention.

- Employee Surveys: Employers use survey research to gather feedback from employees about their job satisfaction, working conditions, and organizational culture. This information is used to improve employee retention and productivity.

- Health Research: Survey research is used in health research to study topics such as disease prevalence, health behaviors, and healthcare access. Researchers use survey data to develop interventions and improve healthcare outcomes.

Examples of Survey Research

Here are some real-time examples of survey research:

- COVID-19 Pandemic Surveys: Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveys have been conducted to gather information about public attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions related to the pandemic. Governments and healthcare organizations have used this data to develop public health strategies and messaging.

- Political Polls During Elections: During election seasons, surveys are used to measure public opinion on political candidates, policies, and issues in real-time. This information is used by political parties to develop campaign strategies and make decisions.

- Customer Feedback Surveys: Companies often use real-time customer feedback surveys to gather insights about customer experience and satisfaction. This information is used to improve products and services quickly.

- Event Surveys: Organizers of events such as conferences and trade shows often use surveys to gather feedback from attendees in real-time. This information can be used to improve future events and make adjustments during the current event.

- Website and App Surveys: Website and app owners use surveys to gather real-time feedback from users about the functionality, user experience, and overall satisfaction with their platforms. This feedback can be used to improve the user experience and retain customers.

- Employee Pulse Surveys: Employers use real-time pulse surveys to gather feedback from employees about their work experience and overall job satisfaction. This feedback is used to make changes in real-time to improve employee retention and productivity.

Survey Sample

Purpose of survey research.

The purpose of survey research is to gather data and insights from a representative sample of individuals. Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people, making it a valuable tool for understanding attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

Here are some common purposes of survey research:

- Descriptive Research: Survey research is often used to describe characteristics of a population or a phenomenon. For example, a survey could be used to describe the characteristics of a particular demographic group, such as age, gender, or income.

- Exploratory Research: Survey research can be used to explore new topics or areas of research. Exploratory surveys are often used to generate hypotheses or identify potential relationships between variables.

- Explanatory Research: Survey research can be used to explain relationships between variables. For example, a survey could be used to determine whether there is a relationship between educational attainment and income.

- Evaluation Research: Survey research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention. For example, a survey could be used to evaluate the impact of a health education program on behavior change.

- Monitoring Research: Survey research can be used to monitor trends or changes over time. For example, a survey could be used to monitor changes in attitudes towards climate change or political candidates over time.

When to use Survey Research

there are certain circumstances where survey research is particularly appropriate. Here are some situations where survey research may be useful:

- When the research question involves attitudes, beliefs, or opinions: Survey research is particularly useful for understanding attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on a particular topic. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a political issue.

- When the research question involves behaviors or experiences: Survey research can also be useful for understanding behaviors and experiences. For example, a survey could be used to understand the prevalence of a particular health behavior.

- When a large sample size is needed: Survey research allows researchers to collect data from a large number of people quickly and efficiently. This makes it a useful method when a large sample size is needed to ensure statistical validity.

- When the research question is time-sensitive: Survey research can be conducted quickly, which makes it a useful method when the research question is time-sensitive. For example, a survey could be used to understand public opinion on a breaking news story.

- When the research question involves a geographically dispersed population: Survey research can be conducted online, which makes it a useful method when the population of interest is geographically dispersed.

How to Conduct Survey Research

Conducting survey research involves several steps that need to be carefully planned and executed. Here is a general overview of the process:

- Define the research question: The first step in conducting survey research is to clearly define the research question. The research question should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the population of interest.

- Develop a survey instrument : The next step is to develop a survey instrument. This can be done using various methods, such as online survey tools or paper surveys. The survey instrument should be designed to elicit the information needed to answer the research question, and should be pre-tested with a small sample of individuals.

- Select a sample : The sample is the group of individuals who will be invited to participate in the survey. The sample should be representative of the population of interest, and the size of the sample should be sufficient to ensure statistical validity.

- Administer the survey: The survey can be administered in various ways, such as online, by mail, or in person. The method of administration should be chosen based on the population of interest and the research question.

- Analyze the data: Once the survey data is collected, it needs to be analyzed. This involves summarizing the data using statistical methods, such as frequency distributions or regression analysis.

- Draw conclusions: The final step is to draw conclusions based on the data analysis. This involves interpreting the results and answering the research question.

Advantages of Survey Research

There are several advantages to using survey research, including:

- Efficient data collection: Survey research allows researchers to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large number of people. This makes it a useful method for gathering information on a wide range of topics.

- Standardized data collection: Surveys are typically standardized, which means that all participants receive the same questions in the same order. This ensures that the data collected is consistent and reliable.

- Cost-effective: Surveys can be conducted online, by mail, or in person, which makes them a cost-effective method of data collection.

- Anonymity: Participants can remain anonymous when responding to a survey. This can encourage participants to be more honest and open in their responses.

- Easy comparison: Surveys allow for easy comparison of data between different groups or over time. This makes it possible to identify trends and patterns in the data.

- Versatility: Surveys can be used to collect data on a wide range of topics, including attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, and preferences.

Limitations of Survey Research

Here are some of the main limitations of survey research:

- Limited depth: Surveys are typically designed to collect quantitative data, which means that they do not provide much depth or detail about people’s experiences or opinions. This can limit the insights that can be gained from the data.

- Potential for bias: Surveys can be affected by various biases, including selection bias, response bias, and social desirability bias. These biases can distort the results and make them less accurate.

- L imited validity: Surveys are only as valid as the questions they ask. If the questions are poorly designed or ambiguous, the results may not accurately reflect the respondents’ attitudes or behaviors.

- Limited generalizability : Survey results are only generalizable to the population from which the sample was drawn. If the sample is not representative of the population, the results may not be generalizable to the larger population.

- Limited ability to capture context: Surveys typically do not capture the context in which attitudes or behaviors occur. This can make it difficult to understand the reasons behind the responses.

- Limited ability to capture complex phenomena: Surveys are not well-suited to capture complex phenomena, such as emotions or the dynamics of interpersonal relationships.

Following is an example of a Survey Sample:

Welcome to our Survey Research Page! We value your opinions and appreciate your participation in this survey. Please answer the questions below as honestly and thoroughly as possible.

1. What is your age?

- A) Under 18

- G) 65 or older

2. What is your highest level of education completed?

- A) Less than high school

- B) High school or equivalent

- C) Some college or technical school

- D) Bachelor’s degree

- E) Graduate or professional degree

3. What is your current employment status?

- A) Employed full-time

- B) Employed part-time

- C) Self-employed

- D) Unemployed

4. How often do you use the internet per day?

- A) Less than 1 hour

- B) 1-3 hours

- C) 3-5 hours

- D) 5-7 hours

- E) More than 7 hours

5. How often do you engage in social media per day?

6. Have you ever participated in a survey research study before?

7. If you have participated in a survey research study before, how was your experience?

- A) Excellent

- E) Very poor

8. What are some of the topics that you would be interested in participating in a survey research study about?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

9. How often would you be willing to participate in survey research studies?

- A) Once a week

- B) Once a month

- C) Once every 6 months

- D) Once a year

10. Any additional comments or suggestions?

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Your feedback is important to us and will help us improve our survey research efforts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- Survey Research: Types, Examples & Methods

Surveys have been proven to be one of the most effective methods of conducting research. They help you to gather relevant data from a large audience, which helps you to arrive at a valid and objective conclusion.

Just like other research methods, survey research had to be conducted the right way to be effective. In this article, we’ll dive into the nitty-gritty of survey research and show you how to get the most out of it.

What is Survey Research?

Survey research is simply a systematic investigation conducted via a survey. In other words, it is a type of research carried out by administering surveys to respondents.

Surveys already serve as a great method of opinion sampling and finding out what people think about different contexts and situations. Applying this to research means you can gather first-hand information from persons affected by specific contexts.

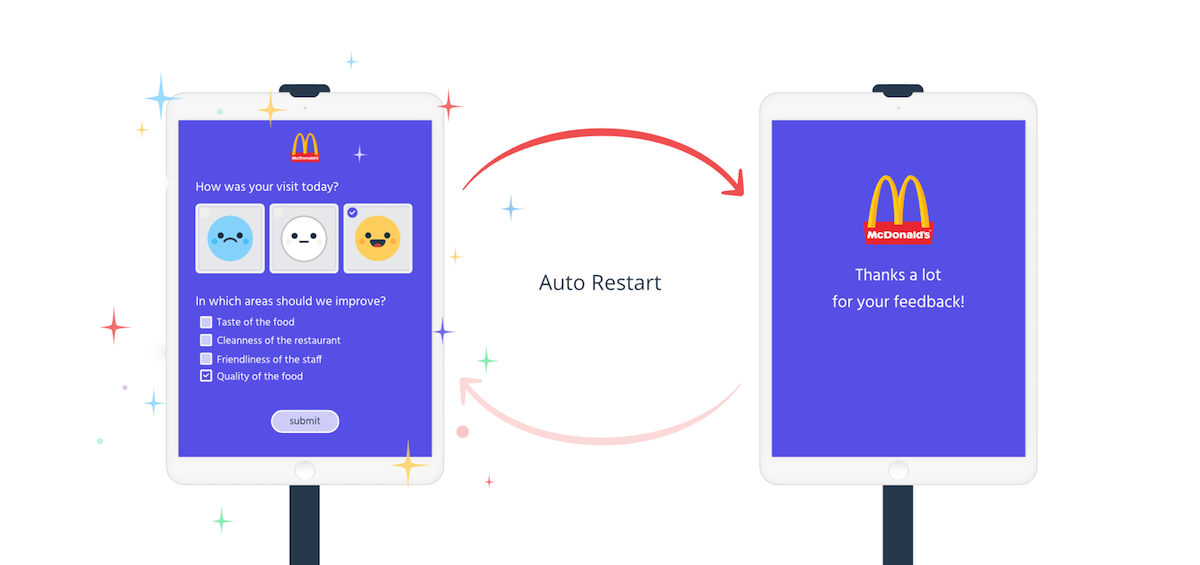

Survey research proves useful in numerous primary research scenarios. Consider the case whereby a restaurant wants to gather feedback from its customers on its new signatory dish. A good way to do this is to conduct survey research on a defined customer demographic.

By doing this, the restaurant is better able to gather primary data from the customers (respondents) with regards to what they think and feel about the new dish across multiple facets. This means they’d have more valid and objective information to work with.

Why Conduct Survey Research?

One of the strongest arguments for survey research is that it helps you gather the most authentic data sets in the systematic investigation. Survey research is a gateway to collecting specific information from defined respondents, first-hand.

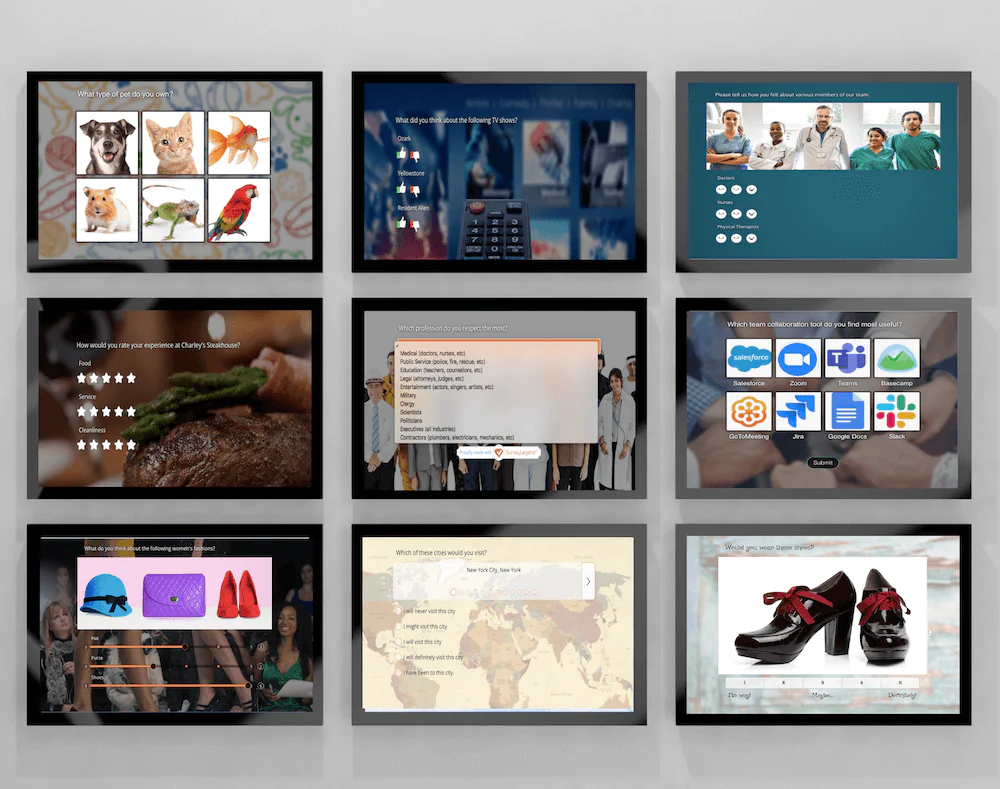

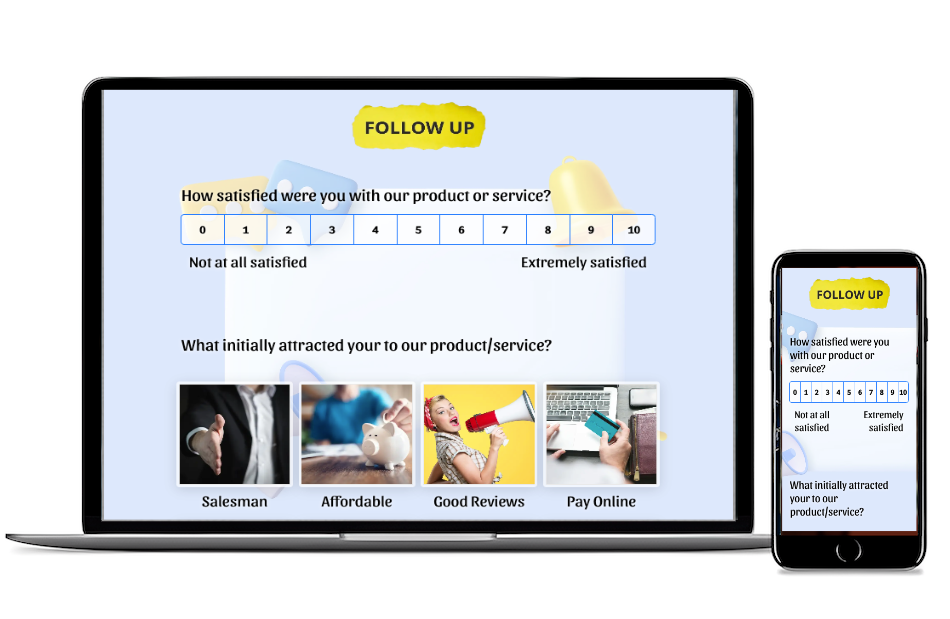

Surveys combine different question types that make it easy for you to collect numerous information from respondents. When you come across a questionnaire for survey research, you’re likely to see a neat blend of close-ended and open-ended questions, together with other survey response scale questions.

Apart from what we’ve discussed so far, here are some other reasons why survey research is important:

- It gives you insights into respondents’ behaviors and preferences which is valid in any systematic investigation.

- Many times, survey research is structured in an interactive manner which makes it easier for respondents to communicate their thoughts and experiences.

- It allows you to gather important data that proves useful for product improvement; especially in market research.

Characteristics of Survey Research

- Usage : Survey research is mostly deployed in the field of social science; especially to gather information about human behavior in different social contexts.

- Systematic : Like other research methods, survey research is systematic. This means that it is usually conducted in line with empirical methods and follows specific processes.

- Replicable : In survey research, applying the same methods often translates to achieving similar results.

- Types : Survey research can be conducted using forms (offline and online) or via structured, semi-structured, and unstructured interviews .

- Data : The data gathered from survey research is mostly quantitative; although it can be qualitative.

- Impartial Sampling : The data sample in survey research is random and not subject to unavoidable biases.

- Ecological Validity : Survey research often makes use of data samples obtained from real-world occurrences.

Types of Survey Research

Survey research can be subdivided into different types based on its objectives, data source, and methodology.

Types of Survey Research Based on Objective

- Exploratory Survey Research

Exploratory survey research is aimed at finding out more about the research context. Here, the survey research pays attention to discovering new ideas and insights about the research subject(s) or contexts.

Exploratory survey research is usually made up of open-ended questions that allow respondents to fully communicate their thoughts and varying perspectives on the subject matter. In many cases, systematic investigation kicks off with an exploratory research survey.

- Predictive Survey Research

This type of research is also referred to as causal survey research because it pays attention to the causative relationship between the variables in the survey research. In other words, predictive survey research pays attention to existing patterns to explain the relationship between two variables.

It can also be referred to as conclusive research because it allows you to identify causal variables and resultant variables; that is cause and effect. Predictive variables allow you to determine the nature of the relationship between the causal variables and the effect to be predicted.

- Descriptive Survey Research

Unlike predictive research, descriptive survey research is largely observational. It is ideal for quantitative research because it helps you to gather numeric data.

The questions listed in descriptive survey research help you to uncover new insights into the actions, thoughts, and feelings of survey respondents. With this data, you can know the extent to which different conditions can be obtained among these subjects.

Types of Survey Research Based on Data Source

- Secondary Data

Survey research can be designed to collect and process secondary data. Secondary data is a type of data that has been collected from primary sources in the past and is readily available for use. It is the type of data that is already existing.

Since secondary data is gathered from third-party sources, it is mostly generic, unlike primary data that is specific to the research context. Common sources of secondary data in survey research include books, data collected through other surveys, online data, data from government archives, and libraries.

- Primary Data

This is the type of research data that is collected directly; that is, data collected from first-hand sources. Primary data is usually tailored to a specific research context so that reflects the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation.

One of the strongest points of primary data over its secondary counterpart is validity. Because it is collected directly from first-hand sources, primary data typically results in objective research findings.

You can collect primary data via interviews, surveys, and questionnaires, and observation methods.

Types of Survey Research Based on Methodology

- Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is a common research method that is used to gather numerical data in a systematic investigation. It is often deployed in research contexts that require statistical information to arrive at valid results such as in social science or science.

For instance, as an organization looking to find out how many persons are using your product in a particular location, you can administer survey research to collect useful quantitative data. Other quantitative research methods include polls, face-to-face interviews, and systematic observation.

- Qualitative Research

This is a method of systematic investigation that is used to collect non-numerical data from research participants. In other words, it is a research method that allows you to gather open-ended information from your target audience.

Typically, organizations deploy qualitative research methods when they need to gather descriptive data from their customers; for example, when they need to collect customer feedback in product evaluation. Qualitative research methods include one-on-one interviews, observation, case studies, and focus groups.

Survey Research Scales

- Nominal Scale

This is a type of survey research scale that uses numbers to label the different answer options in a survey. On a nominal scale , the numbers have no value in themselves; they simply serve as labels for qualitative variables in the survey.

In cases where a nominal scale is used for identification, there is typically a specific one-on-one relationship between the numeric value and the variable it represents. On the other hand, when the variable is used for classification, then each number on the scale serves as a label or a tag.

Examples of Nominal Scale in Survey Research

1. How would you describe your complexion?

2. Have you used this product?

- Ordinal Scale

This is a type of variable measurement scale that arranges answer options in a specific ranking order without necessarily indicating the degree of variation between these options. Ordinal data is qualitative and can be named, ranked, or grouped.

In an ordinal scale , the different properties of the variables are relatively unknown, and it also identifies, describes, and shows the rank of the different variables. With an ordered scale, it is easier for researchers to measure the degree of agreement and/or disagreement with different variables.

With ordinal scales, you can measure non-numerical attributes such as the degree of happiness, agreement, or opposition of respondents in specific contexts. Using an ordinal scale makes it easy for you to compare variables and process survey responses accordingly.

Examples of Ordinal Scale in Survey Research

1. How often do you use this product?

- Prefer not to say

2. How much do you agree with our new policies?

- Totally agree

- Somewhat agree

- Totally disagree

- Interval Scale

This is a type of survey scale that is used to measure variables existing at equal intervals along a common scale. In some way, it combines the attributes of nominal and ordinal scales since it is used where there is order and there is a meaningful difference between 2 variables.

With an interval scale, you can quantify the difference in value between two variables in survey research. In addition to this, you can carry out other mathematical processes like calculating the mean and median of research variables.

Examples of Interval Scale in Survey Research

1. Our customer support team was very effective.

- Completely agree

- Neither agree nor disagree

- Somewhat disagree

- Completely disagree

2. I enjoyed using this product.

Another example of an interval scale can be seen in the Net Promoter Score.

- Ratio Scale

Just like the interval scale, the ratio scale is quantitative and it is used when you need to compare intervals or differences in survey research. It is the highest level of measurement and it is made up of bits and pieces of the other survey scales.

One of the unique features of the ratio scale is it has a true zero and equal intervals between the variables on the scale. This zero indicates an absence of the variable being measured by the scale. Common occurrences of ratio scales can be seen with distance (length), area, and population measurement.

Examples of Ratio Scale in Survey Research

1. How old are you?

- Below 18 years

- 41 and above

2. How many times do you shop in a week?

- Less than twice

- Three times

- More than four times

Uses of Survey Research

- Health Surveys

Survey research is used by health practitioners to gather useful data from patients in different medical and safety contexts. It helps you to gather primary and secondary data about medical conditions and risk factors of multiple diseases and infections.

In addition to this, administering health surveys regularly helps you to monitor the overall health status of your population; whether in the workplace, school, or community. This kind of data can be used to help prevent outbreaks and minimize medical emergencies in these contexts.

Survey research is also useful when conducting polls; whether online or offline. A poll is a data collection tool that helps you to gather public opinion about a particular subject from a well-defined research sample.

By administering survey research, you can gather valid data from a well-defined research sample, and utilize research findings for decision making. For example, during elections, individuals can be asked to choose their preferred leader via questionnaires administered as part of survey research.

- Customer Satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is one of the cores of every organization as it is directly concerned with how well your product or service meets the needs of your clients. Survey research is an effective way to measure customer satisfaction at different intervals.

As a restaurant, for example, you can send out online surveys to customers immediately when they patronize your business. In these surveys, encourage them to provide feedback on their experience and to provide information on how your service delivery can be improved.

Survey research makes data collection and analysis easy during a census. With an online survey tool like Formplus , you can seamlessly gather data during a census without moving from a spot. Formplus has multiple sharing options that help you collect information without stress.

Survey Research Methods

Survey research can be done using different online and offline methods. Let’s examine a few of them here.

- Telephone Surveys

This is a means of conducting survey research via phone calls. In a telephone survey, the researcher places a call to the survey respondents and gathers information from them by asking questions about the research context under consideration.

A telephone survey is a kind of simulation of the face-to-face survey experience since it involves discussing with respondents to gather and process valid data. However, major challenges with this method include the fact that it is expensive and time-consuming.

- Online Surveys

An online survey is a data collection tool used to create and administer surveys and questionnaires using data tools like Formplus. Online surveys work better than paper forms and other offline survey methods because you can easily gather and process data from a large sample size with them.

- Face-to-Face Interviews

Face-to-face interviews for survey research can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured depending on the research context and the type of data you want to collect. If you want to gather qualitative data , then unstructured and semi-structured interviews are the way to go.

On the other hand, if you want to collect quantifiable information from your research sample, conducting a structured interview is the best way to go. Face-to-face interviews can also be time-consuming and cost-intensive. Let’s mention here that face-to-face surveys are one of the most widely used methods of survey data collection.

How to Conduct Research Surveys on Formplus

With Formplus, you can create forms for survey research without any hassles. Follow this step-by-step guide to create and administer online surveys for research via Formplus.

1. Sign up at www.formpl.us to create your Formplus account. If you already have a Formplus account, click here to log in.

5. Use the form customization options to change the appearance of your survey. You can add your organization’s logo to the survey, change the form font and layout, and insert preferred background images.

Advantages of Survey Research

- It is inexpensive – with survey research, you can avoid the cost of in-person interviews. It’s also easy to receive data as you can share your surveys online and get responses from a large demographic

- It is the fastest way to get a large amount of first-hand data

- Surveys allow you to compare the results you get through charts and graphs

- It is versatile as it can be used for any research topic

- Surveys are perfect for anonymous respondents in the research

Disadvantages of Survey Research

- Some questions may not get answers

- People may understand survey questions differently

- It may not be the best option for respondents with visual or hearing impairments as well as a demographic with no literacy levels

- People can provide dishonest answers in a survey research

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve discussed survey research extensively; touching on different important aspects of this concept. As a researcher, organization, individual, or student, it is important to understand how survey research works to utilize it effectively and get the most from this method of systematic investigation.

As we’ve already stated, conducting survey research online is one of the most effective methods of data collection as it allows you to gather valid data from a large group of respondents. If you’re looking to kick off your survey research, you can start by signing up for a Formplus account here.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- survey research

- survey research method

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Goodhart’s Law: Definition, Implications & Examples

In this article, we will discuss Goodhart’s law in different fields, especially in survey research, and how you can avoid it.

Cobra Effect & Perverse Survey Incentives: Definition, Implications & Examples

In this post, we will discuss the origin of the Cobra effect, its implication, and some examples

Cluster Sampling Guide: Types, Methods, Examples & Uses

In this guide, we’d explore different types of cluster sampling and show you how to apply this technique to market research.

Need More Survey Respondents? Best Survey Distribution Methods to Try

This post offers the viable options you can consider when scouting for survey audiences.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Survey research means collecting information about a group of people by asking them questions and analysing the results. To conduct an effective survey, follow these six steps:

- Determine who will participate in the survey

- Decide the type of survey (mail, online, or in-person)

- Design the survey questions and layout

- Distribute the survey

- Analyse the responses

- Write up the results

Surveys are a flexible method of data collection that can be used in many different types of research .

Table of contents

What are surveys used for, step 1: define the population and sample, step 2: decide on the type of survey, step 3: design the survey questions, step 4: distribute the survey and collect responses, step 5: analyse the survey results, step 6: write up the survey results, frequently asked questions about surveys.

Surveys are used as a method of gathering data in many different fields. They are a good choice when you want to find out about the characteristics, preferences, opinions, or beliefs of a group of people.

Common uses of survey research include:

- Social research: Investigating the experiences and characteristics of different social groups

- Market research: Finding out what customers think about products, services, and companies

- Health research: Collecting data from patients about symptoms and treatments

- Politics: Measuring public opinion about parties and policies

- Psychology: Researching personality traits, preferences, and behaviours

Surveys can be used in both cross-sectional studies , where you collect data just once, and longitudinal studies , where you survey the same sample several times over an extended period.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start conducting survey research, you should already have a clear research question that defines what you want to find out. Based on this question, you need to determine exactly who you will target to participate in the survey.

Populations

The target population is the specific group of people that you want to find out about. This group can be very broad or relatively narrow. For example:

- The population of Brazil

- University students in the UK

- Second-generation immigrants in the Netherlands

- Customers of a specific company aged 18 to 24

- British transgender women over the age of 50

Your survey should aim to produce results that can be generalised to the whole population. That means you need to carefully define exactly who you want to draw conclusions about.

It’s rarely possible to survey the entire population of your research – it would be very difficult to get a response from every person in Brazil or every university student in the UK. Instead, you will usually survey a sample from the population.

The sample size depends on how big the population is. You can use an online sample calculator to work out how many responses you need.

There are many sampling methods that allow you to generalise to broad populations. In general, though, the sample should aim to be representative of the population as a whole. The larger and more representative your sample, the more valid your conclusions.

There are two main types of survey:

- A questionnaire , where a list of questions is distributed by post, online, or in person, and respondents fill it out themselves

- An interview , where the researcher asks a set of questions by phone or in person and records the responses

Which type you choose depends on the sample size and location, as well as the focus of the research.

Questionnaires

Sending out a paper survey by post is a common method of gathering demographic information (for example, in a government census of the population).

- You can easily access a large sample.

- You have some control over who is included in the sample (e.g., residents of a specific region).

- The response rate is often low.

Online surveys are a popular choice for students doing dissertation research , due to the low cost and flexibility of this method. There are many online tools available for constructing surveys, such as SurveyMonkey and Google Forms .

- You can quickly access a large sample without constraints on time or location.

- The data is easy to process and analyse.

- The anonymity and accessibility of online surveys mean you have less control over who responds.

If your research focuses on a specific location, you can distribute a written questionnaire to be completed by respondents on the spot. For example, you could approach the customers of a shopping centre or ask all students to complete a questionnaire at the end of a class.

- You can screen respondents to make sure only people in the target population are included in the sample.

- You can collect time- and location-specific data (e.g., the opinions of a shop’s weekday customers).

- The sample size will be smaller, so this method is less suitable for collecting data on broad populations.

Oral interviews are a useful method for smaller sample sizes. They allow you to gather more in-depth information on people’s opinions and preferences. You can conduct interviews by phone or in person.

- You have personal contact with respondents, so you know exactly who will be included in the sample in advance.

- You can clarify questions and ask for follow-up information when necessary.

- The lack of anonymity may cause respondents to answer less honestly, and there is more risk of researcher bias.

Like questionnaires, interviews can be used to collect quantitative data : the researcher records each response as a category or rating and statistically analyses the results. But they are more commonly used to collect qualitative data : the interviewees’ full responses are transcribed and analysed individually to gain a richer understanding of their opinions and feelings.

Next, you need to decide which questions you will ask and how you will ask them. It’s important to consider:

- The type of questions

- The content of the questions

- The phrasing of the questions

- The ordering and layout of the survey

Open-ended vs closed-ended questions

There are two main forms of survey questions: open-ended and closed-ended. Many surveys use a combination of both.

Closed-ended questions give the respondent a predetermined set of answers to choose from. A closed-ended question can include:

- A binary answer (e.g., yes/no or agree/disagree )

- A scale (e.g., a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree )

- A list of options with a single answer possible (e.g., age categories)

- A list of options with multiple answers possible (e.g., leisure interests)

Closed-ended questions are best for quantitative research . They provide you with numerical data that can be statistically analysed to find patterns, trends, and correlations .

Open-ended questions are best for qualitative research. This type of question has no predetermined answers to choose from. Instead, the respondent answers in their own words.

Open questions are most common in interviews, but you can also use them in questionnaires. They are often useful as follow-up questions to ask for more detailed explanations of responses to the closed questions.

The content of the survey questions

To ensure the validity and reliability of your results, you need to carefully consider each question in the survey. All questions should be narrowly focused with enough context for the respondent to answer accurately. Avoid questions that are not directly relevant to the survey’s purpose.

When constructing closed-ended questions, ensure that the options cover all possibilities. If you include a list of options that isn’t exhaustive, you can add an ‘other’ field.

Phrasing the survey questions

In terms of language, the survey questions should be as clear and precise as possible. Tailor the questions to your target population, keeping in mind their level of knowledge of the topic.

Use language that respondents will easily understand, and avoid words with vague or ambiguous meanings. Make sure your questions are phrased neutrally, with no bias towards one answer or another.

Ordering the survey questions

The questions should be arranged in a logical order. Start with easy, non-sensitive, closed-ended questions that will encourage the respondent to continue.

If the survey covers several different topics or themes, group together related questions. You can divide a questionnaire into sections to help respondents understand what is being asked in each part.

If a question refers back to or depends on the answer to a previous question, they should be placed directly next to one another.

Before you start, create a clear plan for where, when, how, and with whom you will conduct the survey. Determine in advance how many responses you require and how you will gain access to the sample.

When you are satisfied that you have created a strong research design suitable for answering your research questions, you can conduct the survey through your method of choice – by post, online, or in person.

There are many methods of analysing the results of your survey. First you have to process the data, usually with the help of a computer program to sort all the responses. You should also cleanse the data by removing incomplete or incorrectly completed responses.

If you asked open-ended questions, you will have to code the responses by assigning labels to each response and organising them into categories or themes. You can also use more qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis , which is especially suitable for analysing interviews.

Statistical analysis is usually conducted using programs like SPSS or Stata. The same set of survey data can be subject to many analyses.

Finally, when you have collected and analysed all the necessary data, you will write it up as part of your thesis, dissertation , or research paper .

In the methodology section, you describe exactly how you conducted the survey. You should explain the types of questions you used, the sampling method, when and where the survey took place, and the response rate. You can include the full questionnaire as an appendix and refer to it in the text if relevant.

Then introduce the analysis by describing how you prepared the data and the statistical methods you used to analyse it. In the results section, you summarise the key results from your analysis.

A Likert scale is a rating scale that quantitatively assesses opinions, attitudes, or behaviours. It is made up of four or more questions that measure a single attitude or trait when response scores are combined.

To use a Likert scale in a survey , you present participants with Likert-type questions or statements, and a continuum of items, usually with five or seven possible responses, to capture their degree of agreement.

Individual Likert-type questions are generally considered ordinal data , because the items have clear rank order, but don’t have an even distribution.

Overall Likert scale scores are sometimes treated as interval data. These scores are considered to have directionality and even spacing between them.

The type of data determines what statistical tests you should use to analyse your data.

A questionnaire is a data collection tool or instrument, while a survey is an overarching research method that involves collecting and analysing data from people using questionnaires.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/surveys/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a likert scale | guide & examples.

- Pollfish School

- Market Research

- Survey Guides

- Get started

- Understanding the 3 Main Types of Survey Research & Putting Them to Use

Understanding the 3 Main Types of Survey Research & Putting Them to Use

Surveys establish a powerful primary source of market research. There are three main types of survey research; understanding these will not merely organize your survey studies, but help you form them from the onset of your research campaign.

It is crucial to be proficient in these types of survey research, as surveys should never be used as lone tools. A survey is a vehicle for granting insights, as part of a larger market research or other research campaigns.

Understanding the three types of survey research will help you learn aspects within these forms that you were either not aware of or were not well-versed in.

This article explores the three main types of survey research and teaches you when to best implement each form of research.

Putting the Types of Survey Research into Perspective

With the presence of online surveys and other market research methods such as focus groups , there are ever-growing survey research methods . Before you choose a method, it is critical to decide on the type of survey research you need to conduct.

The type of survey research points to the kind of study you are going to apply in your campaign and all of its implications . The survey research type essentially hosts the research methods, which house the actual surveys . As such, the research type is one of the highest levels of the process, so consider it as a starting point in your research campaign.

Remember, that while there are various research types, the three presented in this article delineate the main types used in survey research. Researchers can apply these types to other research techniques (such as focus groups, interviews, etc.), but they are best suited for surveys.

Descriptive Research

The first main type of survey research is descriptive research. This type is centered on describing, as its name suggests, a topic of study. This can be a population, an occurrence or a phenomenon.

Descriptive research is often the first type of research applied around a research issue, because it paints a picture of a topic, rather than investigating why it exists to begin with.

The Key Aspects of Descriptive Research

The following provides the key attributes of descriptive research, so as to provide a full understanding of it.

- Makes up the majority of online survey methods.

- Concentrates on the what, when, where and how questions, rather than the why.

- Lays out the particulars surrounding a research topic, but not its origin.

- Handles quantitative studies.

- Deemed conclusive due to its quantitative data.

- Provides data that provides statistical inferences on a target population.

- Preplanned and highly structured.

- Aims to define an occurrence, attitude or opinions of the studied population.

- Measures the significance of the results and formulates trends.

- Can be used in cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys.

Survey Examples of Descriptive Research

There are various types of surveys to use for descriptive research. In fact, you can apply virtually all of them if they meet the above requirements. Here are the major ones:

- Descriptive surveys: These gather data about different subjects. They are set to find how different conditions can be gained by the subjects and the extent thereof. Ex: determining how qualified applicants are to a job are via a survey checking for this.

- Descriptive-normative surveys: Much like descriptive surveys, but the results of the survey are compared with a norm.

- Descriptive analysis surveys: This survey describes a phenomenon via an analysis that divides the subject into 2 parts. Ex: analyzing employees with the same job role across geolocations.

- Correlative Survey: This determines whether the relationship between 2 variables is either positive or negative; sometimes it can be used to find neutrality. For example, if A and B have negative, positive or no correlation.

Exploratory Research

Exploratory research is predicated on unearthing ideas and insights rather than amassing statistics. Also unlike descriptive research, exploratory research is not conclusive. This is because this research is conducted to obtain a better understanding of an existing phenomenon, one that has either not been studied thoroughly or is lacking some information.

Exploratory research is most apt to use at the beginning of a research campaign. In business, this kind of research is necessary for identifying issues within a company, opportunities for growth, adopting new procedures and deciding on which issues require statistical research, i.e., descriptive research.

The Key Aspects of Exploratory Research

Also called interpretative research or grounded theory approach, the following provides the key attributes of exploratory research, including how it differs from descriptive research.

- Uses exploratory questions, which are intended to probe subjects in a qualitative manner.

- Provides quality information that can uncover other unknown issues or solutions.

- Is not meant to provide data that is statistically measurable.

- Used to get a familiarity with an existing problem by understanding its specifics.

- Starts with a general idea with the outcomes of the research being used to find related issues with the research subject.

- Typically exists within open-ended questions.

- Its process varies based on the new insights researchers gain and how they choose to go about them.

- Usually asks for the what, how and most distinctively, the why.

- Due to the absence of past research on the subject, exploratory research is time-consuming,

- Not structured and flexible.

Examples of Exploratory Research

Since exploratory research is not structured and often scattered, it can exist within a multitude of survey types. For example, it can be used in an employee feedback survey, a cross-sectional survey and virtually any other that allows you to ask questions on the why and employs open-ended questions.

Here are a few other ways to conduct exploratory research:

- Case studies: They help researchers analyze existing cases that deal with a similar phenomenon. This method often involves secondary research , unless your business or organization has case studies on a similar topic. Perhaps one of your competitors offers one as well. With case studies, the researcher needs to study all the variables in the case study in relation to their own.

- Field Observations: This method is best suited for researchers who deal with their subjects in physical environments, for example, those studying customers in a store or patients in a clinic. It can also be applied by studying digital behaviors using a session replay tool.

- Focus Groups: This involves a group of people, typically 6-10 coming together and speaking with the researcher, as opposed to having a one on one conversation with the researcher. Participants are chosen to provide insights on the topic of study and express it with other members of the focus group, while the researcher observes and acts as a moderator.

- Interviews : Interviews can be conducted in person or over the phone. Researchers have the option of interviewing their target market, their overall target population, or subject matter experts. The latter will provide significant and professional-grade insights, the kind that non-experts typically can’t offer.

Causal Research

The final type of survey research is causal research, which, much like descriptive research is structured, preplanned and draws quantitative insights. Also called explanatory research, causal research aims to discover whether there is any causality between the relationships of variables.

As such, focuses primarily on cause-and-effect relationships. In this regard, it stands in opposition with descriptive research, which is far broader. Causal research has only two objects:

- Understand which variable are the cause and which are the effect

- Decipher the workings of the relationship between the causal variables, including how they will hammer out the effect.

The Key Aspects of Causal Research

The following provides the key traits of causal research, including how it differs from descriptive and exploratory research.

- Considered conclusive research due to its structured design, preplanning and quantitative nature.

- Its two objectives make this research type more scientific than exploratory and descriptive research.

- Focuses on observing the variations in variables suspected as causing the changes in other variables.

- Measure changes in both the suspected causal variables and the ones they affect.

- Variables suspected of being causal are isolated and tested to meet the aforesaid two objectives.

- For example, an advertisement or a sales promotion

- Requires setting objectives, preplanning parameters, and identifying potential causal variables and affected variables to reduce researcher bias.

- Requires accounting for all the possible causal factors that may be affecting the supposed affected variable, i.e., there can’t be any outside (non-accounted) variables.

- All confounding variables that can affect the results have to be kept consistent and controlled to make sure no hidden variable is in any way influencing the relationship between two variables.

- To deem a cause and effect relationship, the cause would have needed to precede the effect.

Examples of Causal Research

Causal research depends on the most scientific method out of the three types of survey research. Given that it requires experimentation, a vast amount of surveys can be conducted on the variables to determine if they are causal, non-causal or the ones being affected.

Here are a few examples of use causal research

- Product testing: Particularly useful if it’s a new product to test market demand and sales capacity.

- Advertising Improvements: Researchers can study buying behaviors to see if there is any causality between ads and how much people buy or if the advertised products reach higher sales. The outcomes of this research can help marketers tweak their ad campaigns, discard them altogether or even consider product updates.

- Increase customer retention : This can be conducted in different manners, such as via in-store experimentations, via digital shopping or through different surveys. These experiments will help you understand what current customers prefer and what repels them.

- Community Needs : Local governments can conduct the community survey to discover opinions surrounding community issues. For example, researchers can test whether certain local laws, transportation availability and authorizations are well or poorly received and if they correlate with certain happenings.

Deciding on Which of the Types of Research to Conduct

Market researchers and marketers often have several aspects of their discipline that would benefit off of conducting these three types of survey research. What’s most empowering about these types of survey research is that they are not limited to surveys alone.

Instead, they bolster the idea that surveys should not be used as lone tools. Rather, survey research powers an abundance of other market research methods and campaigns. As such, researchers should set aside surveys after they’ve decided on high-level campaigns and their needs.

As such, consider the core of what you need to study. Can your survey be applied to a macro-application? For example, in the business sector, this can be marketing, branding, advertising, etc.

Next, does your study require a methodical approach? For example, does it need to focus on one period of time among one population? If so, you will need to conduct a cross-sectional survey.

Or does it require to be conducted over some period of time? This will require implementing a longitudinal study. Once you figure out these components, you should move on to choosing the type of survey research you’re going to conduct. However, you can also decide on this before you choose one of the methodical methods.

Whichever route you decide to take, you’ll need a strong online survey provider, as this does, after all, involve surveys. The correct online survey platform will set your research up for success.

Frequently asked questions

Why is it important to understand the types of survey research.

The type of survey research informs the kind of study you’ll be conducting. It becomes the backbone of your campaign and all its implications. Basically, the types of survey research host their designated research methods, which house the surveys. Therefore, the types of survey research you decide on are at the highest level of the research process and act as your starting point.

What is exploratory research?

Exploratory research is the most preliminary form of research, establishing the foundation of a research process. focuses on unearthing ideas and insights rather than gathering statistics. It’s not a conclusive form of research-- rather, it is conducted to bolster understanding of a specific phenomenon. It is typically the first form of research, setting the foundation for a research campaign.

What is descriptive research?

Descriptive research focuses on describing a topic of study like a population, an occurrence or a phenomenon. It is performed early on in the overall research process, as it paints an overall picture of a topic, while extracting the key details that you wouldn’t find with exploratory research alone.

What is a cross-sectional survey?

A cross-sectional survey is a survey used to gather research about a particular population at a specific point in time. It is considered to be the snapshot of a studied population.

What is causal research?

Causal research is typically performed in the latter stages of the entire research process, following correlational or descriptive research. It is conducted to find the causality between variables. It involves more than merely observing, as it relies on experiments and the manipulation of variables

How can you decide which types of survey research to conduct?

Take a look at the core of what you need to study. Are you trying to focus on one period of time among a population? Does your survey research need to be conducted over a period of time? Questions like these will lead you to the right research type.

Do you want to distribute your survey? Pollfish offers you access to millions of targeted consumers to get survey responses from $0.95 per complete. Launch your survey today.

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9: Survey Research

Overview of Survey Research

Learning Objectives

- Define what survey research is, including its two important characteristics.

- Describe several different ways that survey research can be used and give some examples.

What Is Survey Research?

Survey research is a quantitative and qualitative method with two important characteristics. First, the variables of interest are measured using self-reports. In essence, survey researchers ask their participants (who are often called respondents in survey research) to report directly on their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Second, considerable attention is paid to the issue of sampling. In particular, survey researchers have a strong preference for large random samples because they provide the most accurate estimates of what is true in the population. In fact, survey research may be the only approach in psychology in which random sampling is routinely used. Beyond these two characteristics, almost anything goes in survey research. Surveys can be long or short. They can be conducted in person, by telephone, through the mail, or over the Internet. They can be about voting intentions, consumer preferences, social attitudes, health, or anything else that it is possible to ask people about and receive meaningful answers. Although survey data are often analyzed using statistics, there are many questions that lend themselves to more qualitative analysis.

Most survey research is nonexperimental. It is used to describe single variables (e.g., the percentage of voters who prefer one presidential candidate or another, the prevalence of schizophrenia in the general population) and also to assess statistical relationships between variables (e.g., the relationship between income and health). But surveys can also be experimental. The study by Lerner and her colleagues is a good example. Their use of self-report measures and a large national sample identifies their work as survey research. But their manipulation of an independent variable (anger vs. fear) to assess its effect on a dependent variable (risk judgments) also identifies their work as experimental.

History and Uses of Survey Research

Survey research may have its roots in English and American “social surveys” conducted around the turn of the 20th century by researchers and reformers who wanted to document the extent of social problems such as poverty (Converse, 1987) [1] . By the 1930s, the US government was conducting surveys to document economic and social conditions in the country. The need to draw conclusions about the entire population helped spur advances in sampling procedures. At about the same time, several researchers who had already made a name for themselves in market research, studying consumer preferences for American businesses, turned their attention to election polling. A watershed event was the presidential election of 1936 between Alf Landon and Franklin Roosevelt. A magazine called Literary Digest conducted a survey by sending ballots (which were also subscription requests) to millions of Americans. Based on this “straw poll,” the editors predicted that Landon would win in a landslide. At the same time, the new pollsters were using scientific methods with much smaller samples to predict just the opposite—that Roosevelt would win in a landslide. In fact, one of them, George Gallup, publicly criticized the methods of Literary Digest before the election and all but guaranteed that his prediction would be correct. And of course it was. (We will consider the reasons that Gallup was right later in this chapter.) Interest in surveying around election times has led to several long-term projects, notably the Canadian Election Studies which has measured opinions of Canadian voters around federal elections since 1965. Anyone can access the data and read about the results of the experiments in these studies.

From market research and election polling, survey research made its way into several academic fields, including political science, sociology, and public health—where it continues to be one of the primary approaches to collecting new data. Beginning in the 1930s, psychologists made important advances in questionnaire design, including techniques that are still used today, such as the Likert scale. (See “What Is a Likert Scale?” in Section 9.2 “Constructing Survey Questionnaires” .) Survey research has a strong historical association with the social psychological study of attitudes, stereotypes, and prejudice. Early attitude researchers were also among the first psychologists to seek larger and more diverse samples than the convenience samples of university students that were routinely used in psychology (and still are).

Survey research continues to be important in psychology today. For example, survey data have been instrumental in estimating the prevalence of various mental disorders and identifying statistical relationships among those disorders and with various other factors. The National Comorbidity Survey is a large-scale mental health survey conducted in the United States . In just one part of this survey, nearly 10,000 adults were given a structured mental health interview in their homes in 2002 and 2003. Table 9.1 presents results on the lifetime prevalence of some anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders. (Lifetime prevalence is the percentage of the population that develops the problem sometime in their lifetime.) Obviously, this kind of information can be of great use both to basic researchers seeking to understand the causes and correlates of mental disorders as well as to clinicians and policymakers who need to understand exactly how common these disorders are.

And as the opening example makes clear, survey research can even be used to conduct experiments to test specific hypotheses about causal relationships between variables. Such studies, when conducted on large and diverse samples, can be a useful supplement to laboratory studies conducted on university students. Although this approach is not a typical use of survey research, it certainly illustrates the flexibility of this method.

Key Takeaways

- Survey research is a quantitative approach that features the use of self-report measures on carefully selected samples. It is a flexible approach that can be used to study a wide variety of basic and applied research questions.

- Survey research has its roots in applied social research, market research, and election polling. It has since become an important approach in many academic disciplines, including political science, sociology, public health, and, of course, psychology.

Discussion: Think of a question that each of the following professionals might try to answer using survey research.

- a social psychologist

- an educational researcher

- a market researcher who works for a supermarket chain

- the mayor of a large city

- the head of a university police force

- Converse, J. M. (1987). Survey research in the United States: Roots and emergence, 1890–1960 . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ↵

- The lifetime prevalence of a disorder is the percentage of people in the population that develop that disorder at any time in their lives. ↵

A quantitative approach in which variables are measured using self-reports from a sample of the population.

Participants of a survey.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Survey research

Survey research is a research method involving the use of standardised questionnaires or interviews to collect data about people and their preferences, thoughts, and behaviours in a systematic manner. Although census surveys were conducted as early as Ancient Egypt, survey as a formal research method was pioneered in the 1930–40s by sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld to examine the effects of the radio on political opinion formation of the United States. This method has since become a very popular method for quantitative research in the social sciences.