- Last edited on September 9, 2020

Homework in CBT

Table of contents, why do homework in cbt, how to deliver homework, strategies to increase confidence.

Homework assignments in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can help your patients educate themselves further, collect thoughts, and modify their thinking.

Homework is not something that you just assign randomly. You should make sure you:

- tailor the homework to the patient

- provide a rationale for why the patient needs to do the homework

- uncover any obstacles that might prevent homework from being done (i.e. - busy work schedule, significant neurovegetative symptoms)

Types of homework

Types of homework assignments.

You should also decide the frequency of the homework should be assigned: should it be daily, weekly?

If your patient does not do homework, that’s OK! Explore as a team, in a non-judgmental way, to explore why the homework was not done. Here are some ways to increase adherence to homework:

- Tailor the assignments to the individual

- Provide a rationale for how and why the assignment might help

- Determine the homework collaboratively

- Try to start the homework during the session. This creates some momentum to continue doing the homework

- Set up systems to remember to do the assignments (phone reminders, sticky notes

- It is better to start with easier homework assignments and err on the side of caution

- They should be 90-100% confident they will be able to do this assignment

- Covert rehearsal - running through a thought experiment on a situation

- Change the assignment - It is far better to substitute an easier homework assignment that patients are likely to do than to have them establish a habit of not doing what they had agreed to in session

- Intellectual/emotional role play - “I’ll be the intellectual part of you; you be the emotional part. You argue as hard as you can against me so I can see all the arguments you’re using not to read your coping cards and start studying. You start.”

The Counseling Palette

Mental health activities to help you and your clients thrive, 1. purchase 2. download 3. print or share with clients.

- Sep 15, 2021

- 10 min read

10 Top CBT Worksheets for Learning Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Updated: Sep 28, 2023

These worksheets cover the most important skills from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

The magic of CBT worksheets is that they take vague concepts and make them real.

Ironically, you need to do more than think about CBT -- your skills must be put into practice!

CBT worksheets help teach and reinforce skills learned in therapy. They are often used by therapists specialized in cognitive behavioral therapy and related treatments.

Below are the 10 top CBT worksheets focused on dealing with anxiety, restructuring thoughts, and addressing trauma and fears.

They can help treat issues like anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias, depression, and more.

Need resources right away? Skip ahead to here take a look at the CBT for anxiety and PTSD bundle.

Article Contents:

1. cbt triangle worksheet.

2. Challenging Thoughts Worksheets

3. Anxiety Management Worksheet

4. Strong Emotions Worksheet

5. Trauma-Focused CBT Worksheet

6. Exposure Hierarchy

7. Trauma Narrative

9 . Emotions Wheel Worksheet

10. Mindfulness Worksheet

CBT worksheets and tools are typically very structured, and follow the cognitive behavioral therapy approach. The basic idea of CBT, or cognitive behavioral therapy , is that patterns of thinking impact everything else. How we think about things can make life better or worse, regardless of the circumstances.

Our thoughts influence our feelings, which lead to our behaviors. The printable worksheets below start with the basic approach and expand into specialized areas, such as using CBT to treat PTSD.

Here are 10 top CBT worksheets focused on thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

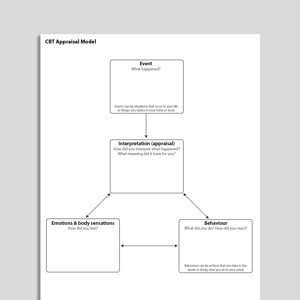

The CBT triangle is a commonly used tool to describe the basic principles of this therapy. This worksheet walks you step by step through the most basic process of CBT. It includes examples as well as space to write your own thoughts and begin to challenge them.

The cognitive (CBT) triangle came out of the early work of Aaron Beck, who developed CBT. He noticed that many people in therapy continued to suffer from mental health conditions such as depression, even as therapy progressed.

He termed the phrase “automatic thoughts,” to describe the thinking pattern many people experience. Most significantly, Dr. Beck found that how people thought about a situation resulted in how they experienced it, regardless of the situation itself.

Most significantly, Dr. Beck found that how people thought about a situation resulted in how they experienced it, regardless of the situation itself.

For example, someone may be running late for work. If they begin to think about getting fired and all of the things that would result from that, they might feel panicked or frustrated, and start driving erratically.

Alternatively, the same person may think differently, coaching themselves in a positive way. They may think, “I rarely run late, and my boss is very understanding, so it will be okay.”

With this change in thinking, they are likely to think more clearly and avoid feeling anxious. They may then calmly text their boss and drive carefully but efficiently toward work.

This process demonstrates the event (running late), the thought (catastrophizing versus positive self-talk) and the behavior (erratic driving versus planning).

Shop CBT triangle worksheet.

2. Challenging Thoughts Worksheet

The challenging thoughts worksheet is a cognitive restructuring worksheet. It walks you through challenging everyday negative thoughts, at a bit of a deeper level than the CBT triangle. It can also be an alternative format to learning the triangle.

Negative thoughts are sometimes called core beliefs, Negative core beliefs are thoughts that tend to pervade our everyday lives. They’re the “issues,” or “triggers,” you just can’t seem to get over. While most negative core beliefs are also distorted beliefs, the reverse isn’t necessarily true.

Negative core beliefs tend to involve shame, and how the person feels about themselves as a whole. This often relates to their abilities and worthiness.

For example, a basic distorted belief might be, “I’ll never pass my algebra class,” while a negative core belief might state, “I’m too stupid to succeed at anything.”

Once you understand the basics of CBT, the next step is to begin to challenge specific thoughts that happen regularly. For example, someone may think, “I mess everything up,” or “I can’t keep any friends.” These thoughts become a habit, and are likely to affect self-esteem, and even become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because someone thinks they can’t keep friends, they stop trying to make them.

This worksheet keeps these thought patterns in mind, and help the user begin to challenge these beliefs. Terms often used include “stuck points,” “cognitive distortions,” or “negative thoughts.”

Shop challenging thoughts worksheet.

While there are multiple types of anxiety conditions, all of them relate to our thoughts. Meanwhile, many CBT therapists start with anxiety management skills. These include steps like mindfulness or self-soothing.

This anxiety management worksheet includes multiple ideas to deal with anxiety, as well as a page to outline your plan for future anxiety spells.

Ongoing anxiety is usually caused by thinking patterns. Ruminating thoughts, catastrophizing, and assuming the worst are common symptoms of multiple conditions. These thought patterns, combined with the hypervigilance that come along with them, can make it difficult to cope day to day.

These anxious thoughts are common, and likely originate from the human need to prepare for the worst and avoid danger. After all, if our ancestors hadn’t been a bit paranoid we may not be here today.

However, frequently thinking negatively can lead to overwhelming anxiety and nearly constant feelings of anxiety. Anxiety worksheets can help with coping while also addressing the root thoughts that perpetuate these fears.

Shop anxiety management worksheet.

4. Dealing With Strong Emotions Worksheet

Strong feelings can be overwhelming. This guide takes a look at how to rate, ride out, or cope with difficult emotions.

For example, if your emotion is simply uncomfortable, it's usually best to wait it out and allow the feeling to move through you. Otherwise it's likely to just keep coming back.

If a feeling is more significant and seems to interfere with your daily life, it may be best to work with a therapist on processing the emotion. Sometimes it's good to face the feeling head on, which will allow your body to learn the difference between the worry about danger and actual danger.

For example, worrying about danger might be thinking about a dog attacking you. It could cause your nervous system to become really alarmed, not realizing that there's no dog in sight.

By staying with that fear, your body will have the experience of getting to the other side and start to figure out that the fear is a feeling and not an event.

In other cases, if you have a history or pattern of self-harm, it's best to work closely with a therapist so you can fine-tune your plan. In some cases you may want to face your emotions while in other cases you may need some soothing to get through the moment.

This CBT worksheet on dealing with strong emotions is a great resource for therapists and their clients to work on feelings together.

Shop strong emotions worksheet.

This worksheet is created for trauma focused CBT Therapies. It includes the most common steps used in therapies like TF-CBT (trauma-focused CBT) and CPT (cognitive processing therapy).

Many people think of PTSD as simply a result of trauma. While trauma is at the core of it, it goes beyond that. The majority of people experience trauma at some point. At first, it causes feelings of worry, confusion, and sometimes self-blame for what happened.

However, within a few weeks to a month, most people come to terms with what happened. They understand that the trauma was an isolated event, and that there wasn’t anything they could do to change it.

A percentage of people, however, aren’t able to get through this process. This could be due to still being in danger, to past trauma complicating their ability to process, or simply having too much going on to deal with it initially.

This lack of processing leads to “stuck points,” or cognitive distortions relating to the trauma. They typically run along the lines of people blaming themselves, or feeling they can’t deal with difficulties in the world.

The most effective trauma therapies all deal with processing of the traumatic event, and this worksheet walks through the typical steps.

Shop the trauma thoughts worksheet.

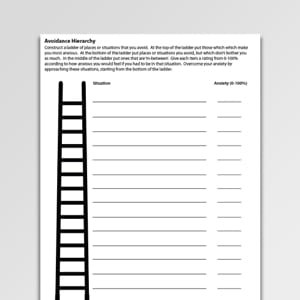

6. Exposure Hierarchy Worksheet

Many people develop avoidance as a way to deal with anxiety, phobias, and PTSD. An exposure hierarchy helps people measure which fears are the worst, and how they progress over time.

This worksheet includes a simple but effective way to create an exposure hierarchy, as well as homework sheets to record your exposure activities.

Exposure, or fear, hierarchies are commonly used in CBT, CPT, and TF-CBT therapies.

Fears are sometimes measured by numbers, called SUDS (subjective units of distress). Over time the fear is tracked, to see if it becomes better or worse.

Most often, exposure hierarchies are used along with homework assignments to help people face their fears. This exposure helps them overcome avoidance that may be interfering with their daily life.

The avoidance hierarchy worksheet includes the basic steps to get started.

Shop the exposure hierarchy worksheet.

The trauma narrative is a technique commonly used in therapies like cognitive processing therapy (CPT), or trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT). This worksheet is written with the client in mind, and should generally be used under the direction of a trained therapist.

A trauma narrative is sometimes used as a part of cognitive behavioral PTSD therapies. It involves writing about memories of a difficult situation.

When someone is experiencing PTSD, it's because their brain is confusing the memory of a bad event with the actual event. Your brain continues to think about what happened, and it keeps your brain on high alert, creating a cycle.

One of the ways to interrupt that process is to write about the difficult memories so that you can integrate them into your life, rather than continue to re-experience them. As mentioned, it's recommended that you work through a trauma narrative as part of trauma-focused CBT therapy.

Shop the trauma narrative worksheet.

8. Kids Anger Worksheet

One of the most common struggle kids deal with are angry outbursts . This is because they haven't had the time to understand and learn how to cope with strong emotions.

Although it doesn't say it outright, this set of kids anger worksheets address the CBT triangle. It uses the anger iceberg as a way to illustrate feelings underlying anger.

It actually is a set of three worksheets covering identifying emotions, recognizing harmful behaviors, and creating more positive behaviors. The worksheets are kid-friendly and work well with TF-CBT therapy for kids.

Shop the kids anger worksheets.

9. Emotions Wheel Worksheet

Emotions are a sometimes overlooked part of CBT treatment. Sometimes people think they should or shouldn't be having certain feelings . They might also be unsure of what they're feeling and when.

However, feelings worksheets help with recognizing, regulating, and coping with emotions. This makes it easier to move into the next step of recognizing how thoughts can relate to ongoing emotional struggles.

Common difficult emotions relating to anxiety, depression, or trauma include:

Frustration

Disappointment

The emotions wheel set includes multiple handouts and worksheets based on feelings wheels. It covers both comfortable and uncomfortable emotions like those above. It also has sections that recognize the physical sensations of emotions, and sections to create your own emotional coping wheel.

Shop the emotions wheel worksheets.

10. Mindfulness for CBT Worksheet

New waves of cognitive therapies, including CBT, incorporate mindfulness. It's an important part of the regulating step, and helps you soothe the flight-or fight response.

It can also make it easier to move onto the next steps of recognizing thoughts and emotions. When your brain is in survival mode it can be difficult to work through challenging thoughts or exposure techniques.

Mindfulness takes it down a notch, much like medication would. It also is a great skill in and of itself, and can prevent mental health, and even some physical conditions, down the road.

Shop the mindfulness worksheet.

CBT Therapy Worksheet Bundle

Over the years, I've found that many of the same strategies overlap for conditions like anxiety and PTSD. At the same time, there are some additional steps necessary when processing trauma. I've bundled all of my related pages into this set .

More CBT Resources

In addition to worksheets, CBT-based games can be a great way to teach important concepts. Here's a list of some of our other activities. You can find them all together in our Giant Store Bundle .

CBT Coping Jeopardy-Like Game

If you're looking for a fun, interactive game for classrooms or telehealth, check this out! It covers many of the CBT concepts in the worksheets. It's a great way to reinforce all of the concepts you're learning. Learn more.

CBT Lingo (Bingo-Like Game)

CBT Lingo is a fun, interactive, educational game that helps you teach concepts of CBT. It goes beyond the typical "novelty" cards often created for therapy and other classroom games. The game is compatible with real bingo, so you can actually "call" the game with numbers, either in-person or via telehealth.

CBT Lingo, which works similar to bingo, includes 75 prompts focused on topics like thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and skills used in cognitive behavioral therapy. It has various options, so it works with teens, college students, and adults.

It can even help with teaching CBT concepts to therapy students.

Here are some sample prompts included in the game:

What does all or nothing thinking mean?

What's one physical symptom of anxiety?

What are the three points of the CBT triangle?

What is ruminating?

Want to give it a go? You can download and use it in-person or via telehealth. Get more details here.

CBT Quest Board Game

CBT board games are another less intimidating way to teach skills. This downloadable board game , called CBT quest, can be printed and used in person, or adapted for online use. It includes 32 prompts with reusable questions, such as:

Give an example of a challenging thought

Describe or show a grounding technique

Describe or name a cognitive distortion

Interested in trying this fun activity? Download it here.

Finding Peace from PTSD Book

If you're working specifically with PTSD, this book is helpful. It lays out the most common strategies used in trauma-focused CBT therapies. Such therapies include:

Prolonged Exposure

Cognitive Processing Therapy

Trauma-Focused CBT

The book was also created to go along with the worksheets in the CBT for PTSD and Anxiety bundle, so the two make great companions! Learn more about the book.

Obviously games and worksheets can’t replace other types of therapy. However, these tools can help you learn to identify thinking patterns, challenge everyday negative thoughts, question your anxiety thoughts, and understand your thoughts relating to PTSD.

For more helpful tools, download it all with our giant store bundle. It includes all of the activities above plus many more great resources .

Sources: Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. 2021, https://beckinstitute.org/

Chand SP, Kuckel DP, Huecker MR. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan.

Recent Posts

7 Magical Steps In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT

5 Common PTSD Symptoms in Women and How to Treat Them

How the CBT Triangle Connects Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

- Childrens CBT

- Couples CBT

01732 808 626 [email protected]

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Worksheets and Exercises

The following Cognitive Behavioural Therapy – CBT worksheets and exercises can be downloaded free of charge for use by individuals undertaking NHS therapy or by NHS practitioners providing CBT in primary or secondary care settings. These worksheets form part of the Think CBT Workbook, which can also be downloaded as a static PDF at the bottom of this page. Please share or link back to our page to help promote access to our free CBT resources.

The Think CBT workbook and worksheets are also available as an interactive/dynamic document that can be completed using mobile devices, tablets and computers. The interactive version of the workbook can be purchased for single use only for £25. All Think CBT clients receive a free interactive/dynamic copy of the workbook and worksheets free of charge.

Whilst these worksheets can be used to support self-help or work with other therapists, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is best delivered with the support of a BABCP accredited CBT specialist. If you want to book an appointment with a professionally accredited CBT expert, call (01732) 808626, complete the simple contact form on the right side of this page or email [email protected]

Please note: if you are a private business or practitioner and wish to use our resources, please email [email protected] to purchase a registered copy. This material is protected by UK copyright law. Please respect copyright ownership.

Exercise 1 - Problem Statements

Download Here

Exercise 2 - Goals for Therapy

Exercise 3 - personal strengths / resources, exercise 4 - costs / benefits of change, exercise 5 - personal values, exercise 6 - the cbt junction model, exercise 7 - the cross-sectional cbt model, exercise 8 - the longitudinal assessment, exercise 9 - layers of cognition, exercise 10 - cognitive distortions, exercise 11 - theory a-b exercise, exercise 12 - the cbt thought record, exercise 13 - cognitive disputation "putting your thoughts on trial", exercise 14 - the cbt continuum, exercise 15 - the self-perception continuum, exercise 16 - the cbt responsibility pie chart, exercise 17 - noticing the thought, exercise 18 - four layers of abstraction, exercise 19 - semantic satiation, exercise 20 - the characterisation game, exercise 21 - speed up / slow down, exercise 22 - word translation, exercise 23 - the time-traveller's log, exercise 23a -the time-traveller's log continued, exercise 24 - leaves on a stream, exercise 25 - the traffic, exercise 26 - clouds in the sky, exercise 27 - taming the ape - an anchoring exercise, exercise 28 - the abc form in functional analysis, exercise 29 - pace activity exercise, exercise 30 - graded hierachy of anxiety provoking situations, exercise 31 - the behavioural experiment, exercise 32 - act exposures exercise, exercise 33 - worry - thinking time, exercise 34 - submissive, assertive & aggressive communication, exercise 35 - sleep hygiene factors, exercises 36 - 38.

(Abdominal Breathing, Aware Breathing & The Five-Minute Daily Recharge Practice)

Exercise 39 - Wheel of Emotions

Exercise 40 - linking feelings and appraisals, exercise 41 - personal resilience plan, exercise 42 - cbt learning log, act with choice exercise, angels and devils worksheet, transdiagnostic model of ocd worksheet, tuning in exercise, penguin-based therapy (pbt), big picture exercise, post-therapy journal, catch it-check it-change it exercise.

A brief cognitive change exercise for identifying and altering negative thinking

Download here

Download The Think CBT Workbook Here

To get a free copy of the 90 page Think CBT Workbook and Skills Primer, click on the download button and save the PDF document to your personal drive or device. The free version of the Think CBT Workbook is presented as a static PDF, so that you can read the document on your device and print worksheets to complete by hand.

In return for a free copy of the workbook, please help us to promote best practice in CBT by sharing this page or linking back to your website or social media profile.

Download a copy

Find CBT Therapists

Complete the following boxes to generate a shortlist of relevant CBT therapist from our team.

Other Therapies

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Child & Adolescent CBT

Clinical Supervision

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Counselling

Dialectical Behaviour Therapy

Employee Assistance

Occupational Psychotherapy

Professional Coaching

Psychometric Assessment

Conditions and Problems

Other links.

Our Services and Charges Our Business Clients CBT Resources Governance Standards Jobs Medico Legal Psychological Tests Therapy Rooms Think CBT Workbook Think CBT Worksheets UK CBT Services

CBT Worksheets, Handouts, And Skills-Development Audio: Therapy Resources for Mental Health Professionals

Resource type

Therapy tool.

"Should" Statements

Information handouts.

A Guide To Emotions (Psychology Tools For Living Well)

Books & Chapters

A Memory Of Caring For Others

A Memory Of Feeling Cared For

Abandonment

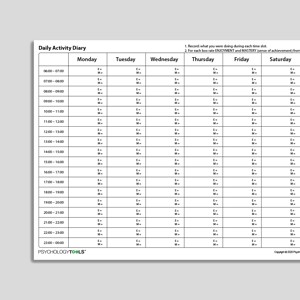

Activity Diary (Hourly Time Intervals)

Activity Diary (No Time Intervals)

Activity Menu

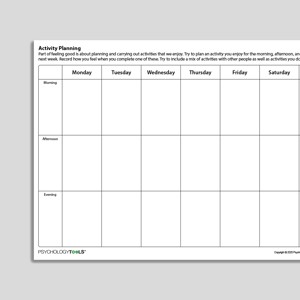

Activity Planning

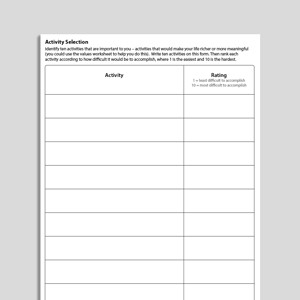

Activity Selection

All-Or-Nothing Thinking

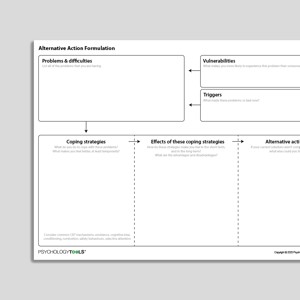

Alternative Action Formulation

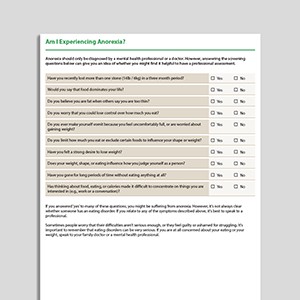

Am I Experiencing Anorexia?

Am I Experiencing Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)?

Am I Experiencing Bulimia?

Am I Experiencing Burnout?

Am I Experiencing Death Anxiety?

Am I Experiencing Depersonalization And Derealization?

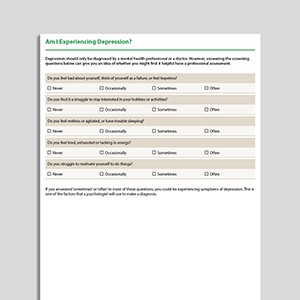

Am I Experiencing Depression?

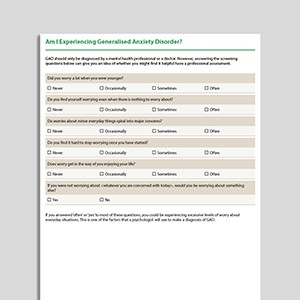

Am I Experiencing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

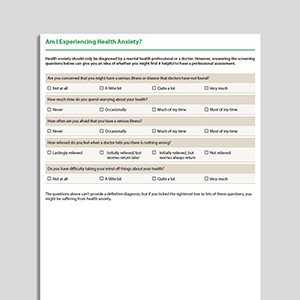

Am I Experiencing Health Anxiety?

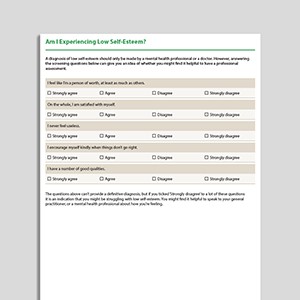

Am I Experiencing Low Self-Esteem?

Am I Experiencing Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)?

Am I Experiencing Panic Attacks?

Am I Experiencing Panic Disorder?

Am I Experiencing Perfectionism?

Am I Experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

Am I Experiencing Psychosis?

Am I Experiencing Social Anxiety?

An Introduction To CBT (Psychology Tools For Living Well)

Anger - Self-Monitoring Record

Anger Decision Sheet

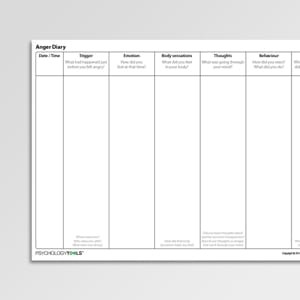

Anger Diary (Archived)

Anger Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

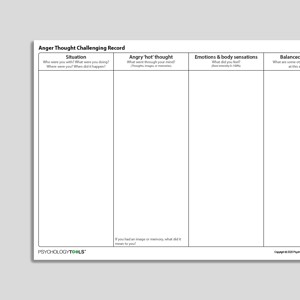

Anger Thought Challenging Record

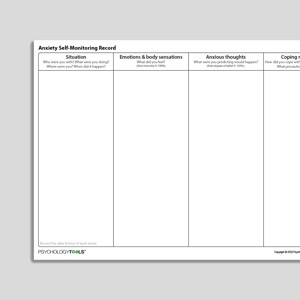

Anxiety - Self-Monitoring Record

Anxiety Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Approach Instead Of Avoiding (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

Approval-/Admiration-Seeking

Arbitrary Inference

Assertive Communication

Assertive Responses

Attention - Self-Monitoring Record

Attention Training Experiment

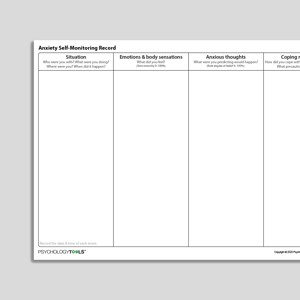

Attention Training Practice Record

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Developing Self-Compassion

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Mindfulness

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Relaxation

Autonomic Nervous System

Avoidance Hierarchy (Archived)

Barriers Abusers Overcome In Order To Abuse

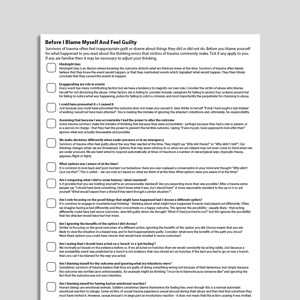

Before I Blame Myself And Feel Guilty

Behavioral Activation Activity Diary

Behavioral Activation Activity Planning Diary

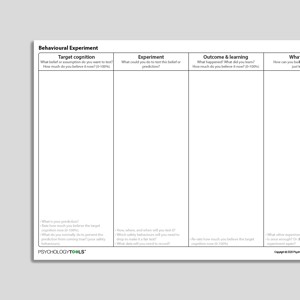

Behavioral Experiment

Behavioral Experiment (Portrait Format)

Behaviors In Panic (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

Being A Compassionate Person

Being With Difficulty (Audio)

Belief Driven Formulation

Belief-O-Meter (CYP)

Body Posture

Body Scan (Audio)

Body Sensations In Panic (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

Boundaries - Self-Monitoring Record

Breathing To Activate Your Soothing System

Breathing To Calm The Body Sensations Of Panic (Psychology Tools For Overcoming Panic)

Broadening Your Perspective

Catastrophizing

Catching Your Thoughts (CYP)

CBT Appraisal Model

CBT Daily Activity Diary With Enjoyment And Mastery Ratings

CBT Thought Record Portrait

CFT Calm Place

Challenging Your Negative Thinking (Archived)

Changing Avoidance (Behavioral Activation)

Checking Certainty And Doubt

Checklist For Better Sleep

Classical Conditioning

Coercive Methods For Enforcing Compliance

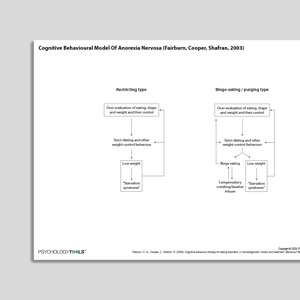

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Anorexia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

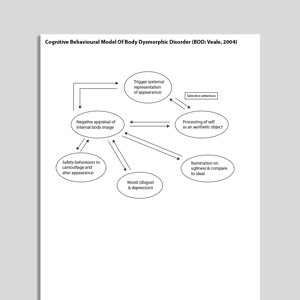

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD: Veale, 2004)

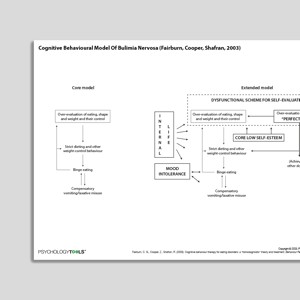

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Bulimia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Clinical Perfectionism (Shafran, Cooper, Fairburn, 2002)

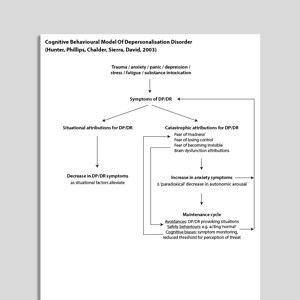

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Depersonalization (Hunter, Phillips, Chalder, Sierra, David, 2003)

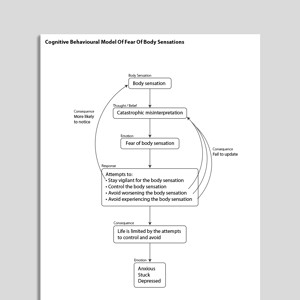

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Fear Of Body Sensations

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD: Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, Freeston, 1998)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Health Anxiety (Salkovskis, Warwick, Deale, 2003)

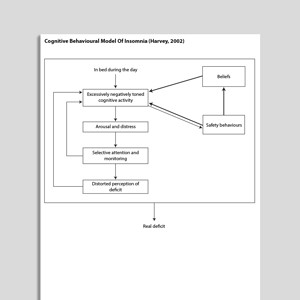

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Insomnia (Harvey, 2002)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Intolerance Of Uncertainty And Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms (Hebert, Dugas, 2019)

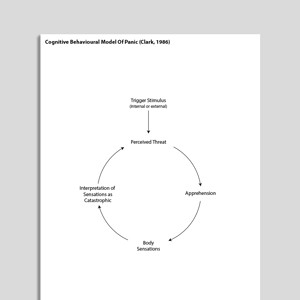

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Panic (Clark, 1986)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD: Whalley, Cane, 2017)

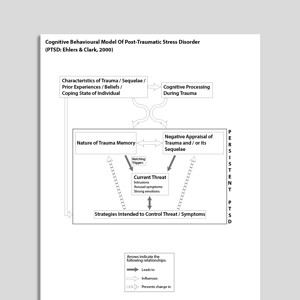

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD: Ehlers & Clark, 2000)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Social Phobia (Clark, Wells, 1995)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of The Relapse Process (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Tinnitus (McKenna, Handscombe, Hoare, Hall, 2014)

Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Of Childhood OCD: It's Only A False Alarm: Therapist Guide

Treatments That Work™

What is Psychology Tools?

Psychology Tools develops and publishes evidence-based psychotherapy resources and tools for mental health professionals. Our online library gives you access to everything you need to deliver more effective therapy and support your practice. With a wide range of topics and resource types covered, you can feel confident knowing you’ll always have a range of accessible and effective materials to support your clients, whatever challenges they are facing, whatever stage you are at, and however you work.

Choose from assessment and case formulations to psychoeducation, interventions and skills development, CBT worksheets, exercises, and much more. Our resources include detailed therapist guidance, references and instructions, so they are equally suitable for those with less experience but who want to expand their practice. Each resource explains how to work with the material most effectively, and how to use it with clients.

Are these resources suitable for you?

Psychology Tools is used by thousands of professionals all over the world as a key part of their practice and preparation, and our resources are designed to be used with clients who experience psychological difficulties or distress. Professionals who use our resources include:

- Clinical, Counseling, and Practitioner Psychologists

- Family Doctors / General Practitioners

- Licensed Clinical Social Workers

- Mental Health Nurses

- Psychiatrists

- Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners

- Psychotherapists

- Therapists (CBT Therapists, ACT Therapists, DBT Therapists)

Psychology Tools resources are perfect for individuals, teams and students, whatever their preferred modality, or career stage.

What kinds of resources are available at Psychology Tools?

Psychology Tools offers a range of relatable, engaging, and evidence-based resources to ensure that your clients get the most out of therapy or counseling. Each resource has been carefully designed with accessibility in mind and is informed by best practice guidelines and the latest scientific research.

Therapeutic exercises are used in many evidence-based psychotherapies including cognitive behavioral therapy, rational emotive behavior therapy, compassion-focused therapy, schema therapy, emotion-focused therapy, systemic family-based therapies, and several others.

Therapists and counselors benefit from incorporating exercises into their work. They can be used to:

- Introduce and explain key concepts.

- Collect information about clients’ difficulties.

- Bring therapeutic ideas to life.

- Keep therapy active and engaging.

- Alleviate distress and/or reduce problematic symptoms.

- Practice new skills and coping strategies.

- Develop new insights and self-awareness.

- Give clients a sense of accomplishment and progress.

Psychology Tools offers a variety of exercises that you can use with your clients as a part of therapy or counseling. These interventions can be incorporated into your sessions, assigned as homework tasks, or used stand-alone interventions. Many of our exercises are either evidence-based (meaning they have been shown to effectively treat certain difficulties) or evidence-derived (meaning they form part of a treatment program that has been shown to effectively treat certain difficulties).

The exercises available at Psychology Tools have a variety of applications. You can use them to:

- Develop case conceptualizations , formulations, and treatment plans.

- Address specific difficulties, such as worry, insomnia, and self-focused attention.

- Introduce clients to new skills, such as grounding , problem-solving, relaxation, and assertiveness .

- Support key interventions, such as exposure and response prevention, safety planning with high-risk clients, and perspective-taking.

- Plan treatments and prepare for supervision.

Psychology Tools exercises have been developed with practicality and convenience in mind. Most exercises include simple step-by-step instructions so that clients can use them independently or with the support of their therapist or counselor. In addition, therapist guidance is available for each exercise, which includes a detailed description of the task, relevant background information, an overview of its aims and potential uses in therapy, and simple instructions for its delivery. A comprehensive list of references is also provided so that you can access key studies and further your understanding of each exercise’s applications in psychotherapy.

Did you know that 40 – 80% of medical information is immediately forgotten by patients (Kessels, 2003)? The same is probably true of therapy and counseling, so clients will almost always benefit from having access to additional written information.

Psychology Tools information handouts provide clear, concise, and reliable information, which will empower your clients to take an active role in their treatment. Learning about their mental health, helpful strategies and techniques, and other psychoeducation topics helps clients better understand and overcome their difficulties. Moreover, clients who understand the process and content of therapy are more likely to invest in the process and commit to making positive changes.

Psychology Tools information handouts can help your clients:

- Understand their difficulties and what keeps them going.

- Learn what therapy is and how it works.

- Understand what they are doing in therapy and why.

- Remember and build upon what has been discussed during sessions.

- Create a personalized collection of resources that can used between appointments.

Our illustrated information handouts cover a wide variety topics. Each has been informed by scientific evidence, best practice guidelines, and expert opinion, ensuring they are both credible and consistent with evidence-based therapies. Topics featured among these resources include:

- ‘ What is… ’ handouts. These one-page resources provide a concise summary of common mental health problems (e.g., anxiety , depression , low self-esteem ), key therapeutic approaches (such as cognitive behavioral therapy, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing , and compassion-focused therapy), and psychological mechanisms which maintain the problem (such as worry and rumination ).

- ‘ What keeps it going… ’ handouts. These handouts explain the key mechanisms that maintain difficulties such as burnout, panic disorder, PTSD, and perfectionism. You can use them to inform your case conceptualization or as a roadmap in therapy.

- ‘ Recognizing… ’ handouts. These guides can help you identify and assess specific disorders, comparing key diagnostic criteria taken from leading diagnostic manuals.

- Simple explanations of key psychological concepts, such as safety behaviors , psychological flexibility, thought suppression, and unhelpful thinking styles .

- Overviews of important psychological theories, such as operant conditioning and exposure.

Each information handout comes with guidance written specifically for therapists and counselors. It provides suggestions for introducing psychoeducation topics, facilitating helpful discussions related to the handout, and ensuring the content is relevant to your clients.

Worksheets are a core ingredient of many evidence-based therapies such as CBT. Our worksheets take many forms (e.g., diaries, diagrams, activity planners, records, and questionnaires) and can be used throughout the course of therapy.

How you incorporate worksheets into therapy or counselling depends on each client’s difficulties, goals, and stage of recovery. You can use them to:

- Assess and monitor clients’ difficulties.

- Inform treatment plans and guide decision-making.

- Teach clients new skills such as ‘self-monitoring’ or ‘thought challenging’.

- Ensure that clients apply their learning in the real world.

- Track their progress over time.

- Help clients to take an active role in their recovery.

Clients also benefit from using worksheets. These tools can help them:

- Become more aware of their difficulties.

- Identify when, how, and why these problems occur.

- Practice using new skills and techniques.

- Express and explore difficult feelings.

- Process difficult events.

- Consolidate and integrate insights from therapy.

- Support their self-reflection.

- Feel empowered and build self-efficacy.

Psychology Tools offers a wide variety of worksheets. They include general forms that are widely applicable, disorder-specific worksheets, and logs that are used in specific therapies such as CBT , schema therapy, and compassion-focused therapy . These resources are typically available in editable or fillable formats, so that they can be tailored to your client’s needs and used in a flexible manner.

Guides & self-help

People want clear guidance on mental health, whether for themselves or a loved one.

Our ‘ Understanding… ’ series is designed to introduce common mental health difficulties such as depression, PTSD, or social anxiety. Each of these guide uses a clear and accessible structure so that readers can understand them without any prior therapy knowledge. Topics addressed in each guide include:

- What the problem is.

- How it arises.

- Where it might come from.

- What keeps it going.

- How the problem can be treated.

Other guides address important topics such as trauma and dissociation, or the effects of perfectionism. They usually contain a mixture of psychoeducation, practical exercises and skills development. They promote knowledge, optimism, and positive action related to these difficulties, and have been informed by current research and evidence-based treatments, ensuring they are consistent with best practices.

Therapists can use Psychology Tools guides in several ways:

- As a screening tool. Clients can read the guide to see if the difficulty or topic is relevant to them.

- As psychoeducation. Each guide provides essential information related to the difficulty or topic so that client can develop a better understanding of it.

- As self-help. Each guide describes key skills and techniques that can be used to overcome the difficulty.

Each guide contains informative illustrations, practical examples, and simple instructions so that clients can easily relate to the content and apply it to their difficulties.

Therapy audio

Audio exercises are a particularly convenient and engaging way help your clients and can add variety to your therapeutic toolkit. Psychology Tools audio resources can help your clients:

- Augment and consolidate their learning in therapy.

- Practice new techniques.

- Integrate skills and practices into their daily lives.

- Access additional support when they need it.

- Create a sense a continuity between your meetings.

A variety of audio resources are available at Psychology Tools. Each one has been developed and recorded by highly experienced clinical psychologists and can be easily integrated into your therapeutic practice. Audio collections include:

- Psychology Tools for Developing Self-Compassion

- Psychology Tools for Relaxation

- Psychology Tools for Mindfulness

- Psychology Tools for Overcoming PTSD

Many of these audio resources are widely applicable (e.g., mindfulness-based tools), although problem-specific resources are also available (e.g., tools for overcoming PTSD). You can use these tools:

- During your therapy sessions.

- As a homework task for clients to complete.

- As a stand-alone intervention or ongoing part of therapy.

Treatments That Work®

Authored by leading psychologists including David Barlow, Michelle Craske, and Edna Foa, Treatments That Work ® is a series of workbooks based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Each pair of books in the series – therapist guide and workbook – contains step by step procedures for delivering evidence-based psychological interventions. Clinical illustrations and worksheets are provided throughout.

You can use these workbooks:

- To plan treatment for a range of specific difficulties including depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety, and substance use.

- As a self-help intervention that you guide the client through during sessions.

- As a supplement to therapy, which clients work through independently.

- To consolidate the content of your sessions.

- As an ongoing intervention at the end of treatment (e.g., for difficulties that haven’t been fully addressed).

Each book is available to download chapter-by-chapter, and Psychology Tools members with a currently active subscription to our ‘Complete’ plan are licensed to share copies with their clients.

Archived resources

We work hard to keep all resources up to date, so we regularly review and update our library. However, we understand that you might get used to a certain version of a resource as part of your workflow. Instead of removing older versions, we keep them in our archive so that you can still access them if you want to. We also clearly explain if an improved version is available, so you can choose which you prefer.

Series and ranges

As well as many topic-specific resources, we also publish a variety of ranges and series.

- The ‘What is…’ series. These one-page resources cover a range of common mental health problems. In client friendly language they provide a concise summary of the problem, what it can feel like, what maintains it and an overview of key evidence-based therapeutic approaches (e.g., CBT, EMDR, and compassion-focused therapy) to treatment.

- The ‘What keeps it going…’ series . These are one-page diagrams that explain what tends to maintain common mental health conditions such as burnout, panic disorder, PTSD, and perfectionism. You can use them to inform your case conceptualization or as a roadmap in therapy. They provide a quick and easy way for clients to understand why their disorder persists and how it might be interrupted.

- The ‘Recognizing…’ series can help you identify and assess specific disorders, comparing key diagnostic criteria from leading diagnostic manuals.

- The ‘Understanding…’ series is a collection of psychoeducation guides for common mental health conditions. Friendly and explanatory, they are comprehensive sources of information for your clients. Concepts are explained in an easily digestible way with plenty of case examples and diagrams. Each guide covers symptoms, treatments and some key maintenance factors .

- The ‘Guide to…’ resources give clients a deep dive into a condition or treatment approach. They cover a mixture of information, psychoeducation, practical exercises and skills development to help clients learn to manage their condition. Each of these guides offers psychoeducation about the topic alongside a range of practical exercises with clear instructions to help clients identify, monitor, and address their symptoms.

- The ‘ Self-monitoring’ collection provides problem-specific records designed to help you and your clients get the most from this essential but often overlooked technique. Covering a broad range of conditions, these worksheets allow you to give clients a tool that is targeted to their experience, with relevant language and prompts.

- The ‘Formulation’ series provides a client-friendly adaptation of cognitive behavioral models for disorders including panic, PTSD, and social anxiety. These useful tools can help you and your clients come to a shared understanding of their difficulties, and can help you to develop a roadmap for therapy.

Multilingual library of translations

Did you know that Psychology Tools has the largest online, searchable library of multilingual therapy resources? We aim to make our resources accessible to everyone. With over 3500 resources across 70 languages, you can give clients resources in their native language, enabling a deeper understanding and engagement with the treatment process. Translations are carried out by specially selected professional translators with experience of psychology, and our pool of volunteer mental health professionals. We also make sure that the resource design is the same for each translated resource so that you can be confident you know what section you are looking at, even if you don’t speak the language.

Simply find the resource you want to use, then explore which languages that resource is available in, or you can see all the resources available in a particular language by using our search filters.

What formats are the resources available in, and how can I use them?

People work in different ways. Our formats are designed to reflect that, so you can choose the style that suits how you and your client want to work. Psychology Tools resources are perfectly formatted to work whether you practice face to face, remotely, or use a blended approach.

- Professional version. Designed for clinicians, this comprehensive option includes everything you need to use the resource confidently. As well as the resource, each PDF contains useful information, including therapist guidance explaining how to use the resource most effectively, descriptions that provide theoretical context, instructions, therapist prompts, and references. Some resources also include case examples and annotations where appropriate.

- Client version. This is a blank PDF of the resource, with client-friendly instructions where appropriate, but without the theoretical description. These are ideal for printing and using in-session, or giving to a client.

- Fillable PDFs are great for clients who want to work with resources online instead of on paper. Your client can fill in and save the resource on a computer, before sending it back to you without the need for a printer. This format is also useful if you have remote sessions with clients and want to work through a resource on screen together.

- Editable PowerPoint documents are useful if you want to make any changes to the resource structure, or personalize it for your client.

- Editable Word documents are also useful if you want to make changes to the resource, and are more suited to printing.

How do we design our resources to support your practice?

Our resources are informed by evidence-based treatments, best practice guidelines, and the latest published research. They are written by highly experienced therapists and experts in mental health, ensuring they are effective and as up to date as possible. In addition, every resource goes through a rigorous peer review process to confirm they are accurate and easy to use.

Each resource is designed with both clients’ and therapists’ needs in mind. For clients, that means using clear, user-friendly language, as well as plenty of visual and case examples, illustrations, diagrams and vignettes that readers can relate to. They include information on how the resource can help them, how they should use it, and other useful tips.

We also include useful information and descriptions for clinicians to help them use the resource most effectively. The therapist versions of each resource contain therapist guidance, prompts, instructions, and full references. They outline how the resource can be used and what types of problems it could be helpful for.

- Designed to make strong theory-practice links . We pay close attention to the theory underpinning our resources, which provides therapists with useful context and helps them make theory-practice links. Having a greater understanding of each tool ensures best practice.

- One concept per page. Wherever possible, we create resources using the principle of one therapeutic concept per page, as this ensures that we have distilled the idea down to its essence. This makes each tool simple for therapists to communicate and easy for clients to grasp. We also pay close attention to visual layout and design, to make our resources as accessible as possible. Every resource aims to maximize clinical benefit and engagement, without overwhelming readers.

- Action focused. Resources are designed to be interactive, collaborative and goal-focused, with prompts to facilitate self-monitoring of progress and goals.

How can I use this page?

This page is where you can explore all the resources in the Psychology Tools library. The different search filters on the left-hand side enable you to customize your search, depending on what you need. Materials are organized by resource type, problem, and therapy tool, though you can also filter by language or use the search box. You can find more detailed instructions for how to find resources here .

Can I share resources directly with my clients?

If you have a paid Psychology Tools membership, you are licensed to share resources with clients in the course of your professional work. You can even email resources (even large audio collections) directly to your clients from our website. All emails are secure and encrypted, so it is a quick and easy way to save you time and facilitate clients’ self-practice.

What if I need more help?

We have a wide range of ‘ How-to’ guides and an FAQ in our help centre , which answers questions on how to use the library and tools, such as ‘ How do I download resources? ’ or ‘ How do I email resources to my clients directly from the website? ’.

Kessels, R. P. C. (2003). Patients’ memory for medical information . Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96 , 219-222.

- For clinicians

- For students

- Resources at your fingertips

- Designed for effectiveness

- Resources by problem

- Translation Project

- Help center

- Try us for free

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Free Therapy Techniques

- Anxiety Treatment

- Business and Marketing

- CBT Techniques

- Client Motivation

- Dealing With Difficult Clients

- Hypnotherapy Techniques

- Insomnia and Sleep

- Personal Skills

- Practitioner in Focus

- Psychology Research

- Psychotherapy Techniques

- PTSD, Trauma and Phobias

- Relationships

- Self Esteem

- Sensible Psychology Dictionary

- Smoking Cessation and Addiction

- The Dark Side of Your Emotional Needs

- Uncommon Philosophy

Top 10 CBT Worksheets Websites

The best cognitive behavioural therapy resources, activities and assignments all in one place.

Hi, it’s Rosie here, Uncommon Knowledge’s content manager. I’ve been hearing a lot from practitioners who use Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and are on the lookout for new resources, especially CBT worksheets.

So to flesh out our resources, I’ve had this list put together, which features ten of the best websites featuring CBT worksheets.

Where to find CBT worksheets

CBT is one of the most widely used therapeutic treatment approaches in mental health today. Because it is an action-oriented approach, homework is a key aspect of the change process. And CBT tools such as worksheets, activity assignments, bibliotherapy and guided imagery can all be useful homework assignments.

But finding those clinically-sound, cost-effective and easy-to-access resources can be the therapist’s challenge. There’s not always time to sift through books or surf the ‘net looking for those CBT worksheets or teaching tools that are “just right”. Aside from staying on schedule, you want to spend time with your clients, helping them achieve their goals.

So here’s a list of ten of the best CBT resource sites for you to use as a reference point for your practice:

1. Therapist Aid

Free reframing book just subscribe to my therapy techniques newsletter below..

Download my book on reframing, "New Ways of Seeing", when you subscribe for free email updates

Click to subscribe free now

The site contains a huge selection of CBT worksheets as well as videos, guides and other resources. ‘The ABC model of CBT’ is a particularly good video to help clients understand the relationship between their thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

2. Psychology Tools

Psychology Tools is another one of those really great sites that has been created by practitioners for practitioners. It was designed as a way to share materials among therapists. The site offers a number of CBT-specific articles, assessments and tools for clinical use. There is also a self-help section.

One of the strengths of this site is that it offers resources for several other therapies including ACT, DBT and EMDR. Therapists can also submit their own worksheets or other resources for consideration of inclusion on the website.

3. Excel At Life

Guided imagery and mindfulness meditation are often used as part of a CBT approach to treatment. This site offers a range of free audio downloads for a variety of needs. These downloads can be used in the office or as part of a homework assignment.

This site offers several CBT resources for the practitioner as well as the client seeking self-directed support including informative articles and forms such as a mood diary and various questionnaires. This site is exceptionally user-friendly.

4. Living CBT

This site offers a number of worksheets and tools including diary forms, action plans and a number of helpful self-statements that are great for sharing with clients. The tools are mostly in PDF and are easy to download. The site also offers several self-help books for purchase.

Aside from the self-help section, this site also has a Free CBT Therapist Resources section. The tools available here are similar to those found in the general section but some are more appropriate for use in the clinical setting.

5. Veronica Walsh’s CBT Blog

This site is a great little gem chock full of CBT resources and downloads. Worksheets cover everything from a CBT journaling guide to incorporating mindfulness to using CBT with cyberbullying. Spend a little time on this site and you’ll find all kinds of useful tools that you and your client can work with. The owner of this site has put a lot of work into making a plethora of resources available to the user.

6. Specialty Behavioral Health

This site offers a variety of worksheets for the practitioner as well as worksheets specifically for CBT. They are well-designed and easily adapted to a variety of clients. Two worksheets to check out are the ‘Ways to Challenge Your Thoughts’ and the ‘Procrastination Profiles’, as well as accompanying ‘Task Master Worksheet (for Procrastination)’. These are nicely done and would be particularly useful with the client struggling to understand thought patterns and challenging negative thinking.

7. GetSelfHelp

This website provides a number of CBT self-help and therapy resources, including downloadable worksheets, information sheets and CBT formulations.

One of the standouts of this site is the 40-page CBT-based self-help course. It’s free and chock full of information and tools to help your clients understand and implement changes. You can find the course here.

8. Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust

This is a 52-page fully downloadable CBT workbook from the Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust. It is full of client-friendly descriptions, activities and tools for setting and achieving goals. This workbook is the kind of tool that can be used by the therapist with a client or as a self-help tool for self-motivated clients.

9. Martin CBT

This site is often mentioned when the question of CBT resources comes up. While not as extensive an offering as some sites, the forms and tools found here are well-produced, immediately usable and user-friendly.

One of the highlights is the ‘Cycle of Maladaptive Behavior’ sheet. Clients don’t always understand the cycle and how their behaviours manifest. This worksheet does a good job of describing the cycle and how it unfolds. The site also offers an excellent handout with examples and descriptions of cognitive distortions. Definitely worth a visit!

10. EPISCenter

A list of CBT worksheets would not be complete without including a few child specific resources. CBT has been shown to be effective with children, especially in trauma work.

This workbook is an excellent resource for CBT and trauma work with children. There are relatively few tools specifically designed for children. This workbook is particularly well-constructed and child-friendly.

So there you have it. Ten of the best sites out there for CBT resources and tools. Are there more out there? You bet! There are lots of great resources out there for every level of need and every type of problem. But these sites represent some of the best of what’s out there and will get you started in working with your clients using CBT worksheets. You’ll have more time with your clients and your clients will benefit from having some of the best tools out there.

Update: This post was so popular with readers we added another! Read 10 More Top CBT Worksheets Websites here .

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is an important part of the treatment jigsaw and our co-founder Mark Tyrrell would want me to mention the following articles we already have available, in the spirit of setting it in a wider context:

- 3 Instantly Calming CBT Techniques for Anxiety

- The Sensible Psychology Dictionary defines CBT

Would you like to enhance your reframing skills?

Click here to read how my online course ‘Conversational Reframing’ shows you how to craft cunning reframes and slip them past your clients’ conscious criticisms.

About Mark Tyrrell

Psychology is my passion. I've been a psychotherapist trainer since 1998, specializing in brief, solution focused approaches. I now teach practitioners all over the world via our online courses .

You can get my book FREE when you subscribe to my therapy techniques newsletter. Click here to subscribe free now.

You can also get my articles on YouTube , find me on Instagram , Amazon , Twitter , and Facebook .

Related articles:

Read more CBT Techniques therapy techniques »

Search for more therapy techniques:

- Odnoklassniki

- Facebook Messenger

- LiveJournal

Sending Homework to Clients in Therapy: The Easy Way

Successful therapy relies on using assignments outside of sessions to reinforce learning and practice newly acquired skills in real-world settings (Mausbach et al., 2010).

Up to 50% of clients don’t adhere to homework compliance, often leading to failure in CBT and other therapies (Tang & Kreindler, 2017).

In this article, we explore how to use technology to create homework, send it out, and track its completion to ensure compliance.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Is homework in therapy important, how to send homework to clients easily, homework in quenza: 5 examples of assignments, 5 counseling homework ideas and worksheets, using care pathways & quenza’s pathway builder, a take-home message.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy has “been shown to be as effective as medications in the treatment of a number of psychiatric illnesses” (Tang & Kreindler, 2017, p. 1).

Homework is a vital component of CBT, typically involving completing a structured and focused activity between sessions.

Practicing what was learned in therapy helps clients deal with specific symptoms and learn how to generalize them in real-life settings (Mausbach et al., 2010).

CBT practitioners use homework to help their clients, and it might include symptom logs, self-reflective journals , and specific tools for working on obsessions and compulsions. Such tasks, performed outside therapy sessions, can be divided into three types (Tang & Kreindler, 2017):

- Psychoeducation Reading materials are incredibly important early on in therapy to educate clients regarding their symptoms, possible causes, and potential treatments.

- Self-assessment Monitoring their moods and completing thought records can help clients recognize associations between their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.

- Modality specific Therapists may assign homework that is specific and appropriate to the problem the client is presenting. For example, a practitioner may use images of spiders for someone with arachnophobia.

Therapists strategically create homework to lessen patients’ psychopathology and encourage clients to practice skills learned during therapy sessions, but non-adherence (between 20% and 50%) remains one of the most cited reasons for CBT failure (Tang & Kreindler, 2017).

Reasons why clients might fail to complete homework include (Tang & Kreindler, 2017):

Internal factors

- Lack of motivation to change what is happening when experiencing negative feelings

- Being unable to identify automatic thoughts

- Failing to see the importance or relevance of homework

- Impatience and the wish to see immediate results

External factors

- Effort required to complete pen-and-paper exercises

- Inconvenience and amount of time to complete

- Failing to understand the purpose of the homework, possibly due to lack of or weak instruction

- Difficulties encountered during completion

Homework compliance is associated with short-term and long-term improvement of many disorders and unhealthy behaviors, including anxiety, depression, pathological behaviors, smoking, and drug dependence (Tang & Kreindler, 2017).

Greater homework adherence increases the likelihood of beneficial therapy outcomes (Mausbach et al., 2010).

With that in mind, therapy must find ways to encourage the completion of tasks set for the client. Technology may provide the answer.

The increased availability of internet-connected devices, improved software, and widespread internet access enable portable, practical tools to enhance homework compliance (Tang & Kreindler, 2017).

Clients who complete their homework assignments progress better than those who don’t (Beck, 2011).

Having an ideal platform for therapy makes it easy to send and track clients’ progress through assignments. It must be “user-friendly, accessible, reliable and secure from the perspective of both coach and client” (Ribbers & Waringa, 2015, p. 103).

In dedicated online therapy and coaching software, homework management is straightforward. The therapist creates the homework then forwards it to the client. They receive a notification and complete the work when it suits them. All this is achieved in one system, asynchronously; neither party needs to be online at the same time.

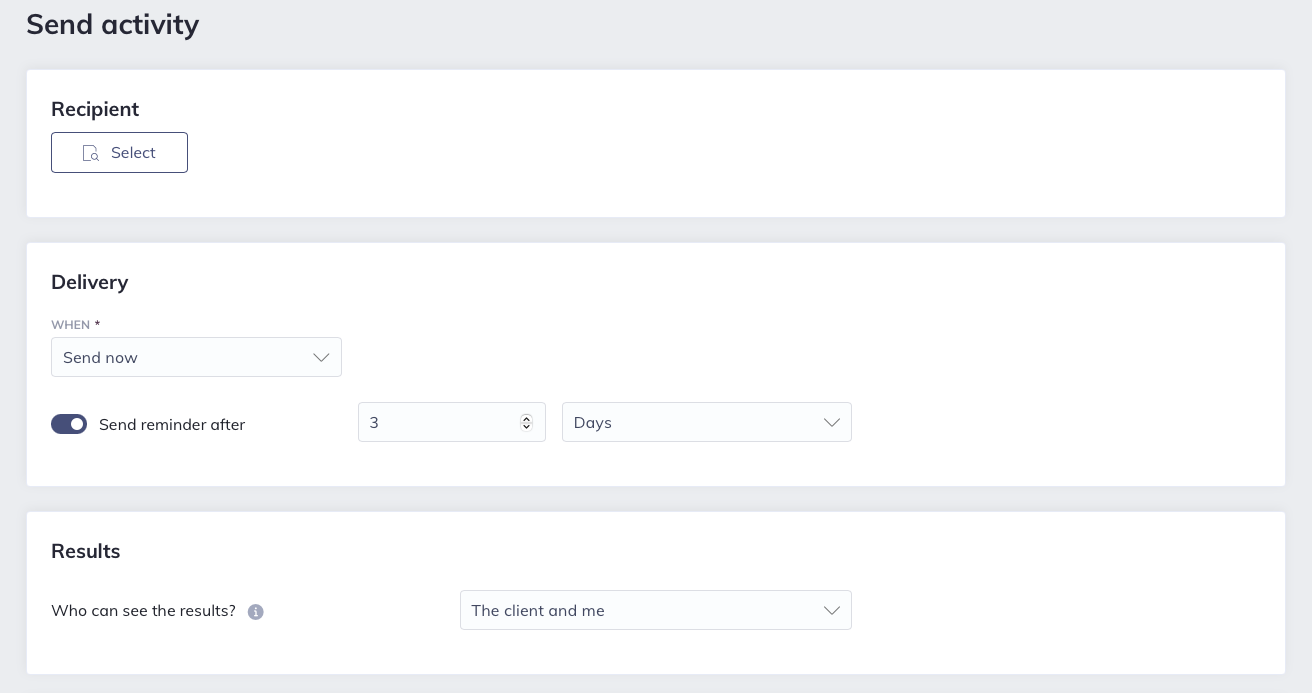

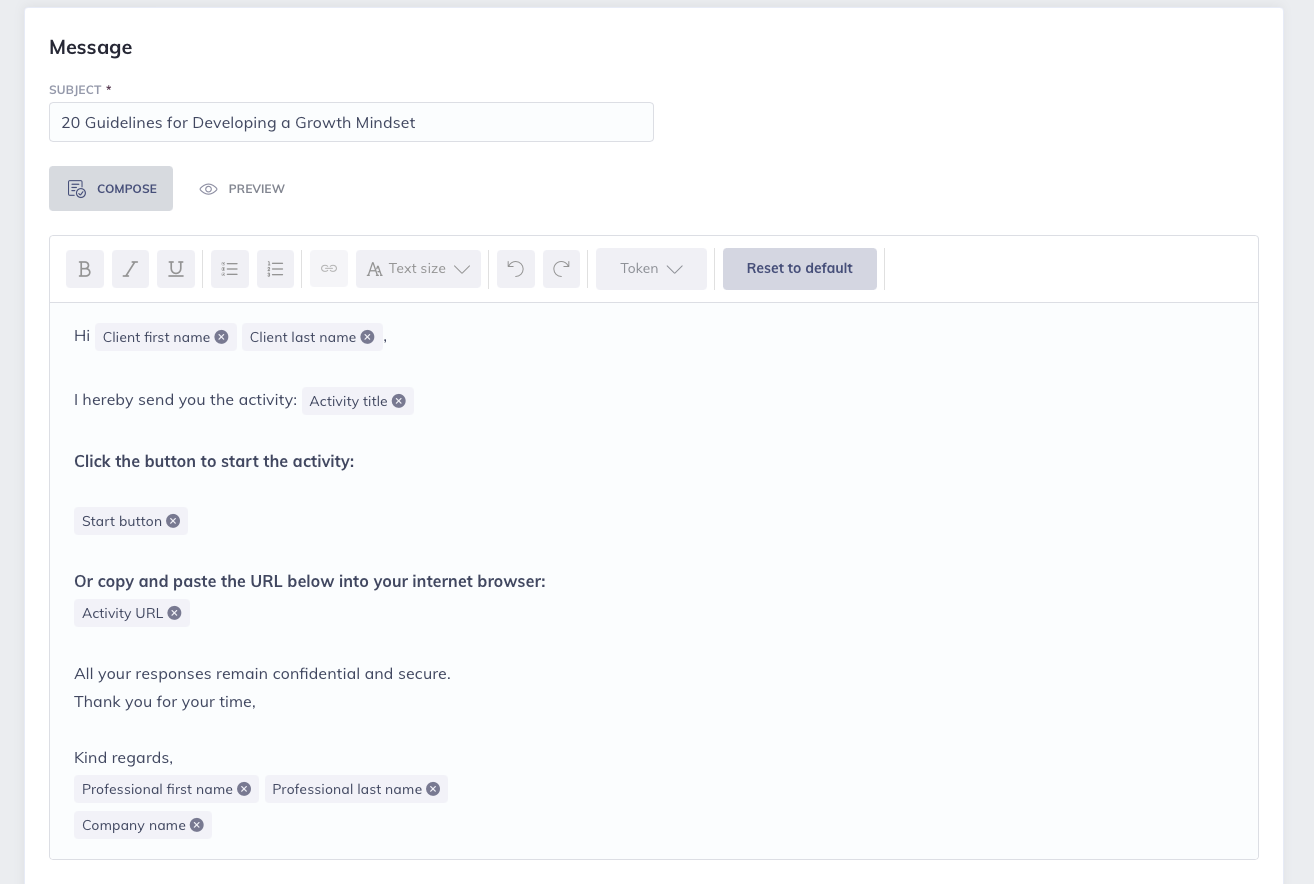

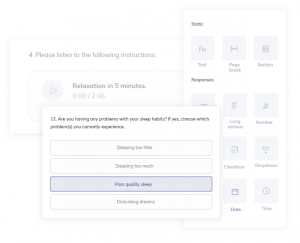

For example, in Quenza , the therapist can create a worksheet or tailor an existing one from the library as an activity that asks the client to reflect on the progress they have made or work they have completed.

The activity can either be given directly to the client or group, or included in a pathway containing other activities.

Here is an example of the activity parameters that Quenza makes possible.

A message can be attached to the activity, using either a template or a personally tailored message for the client. Here’s an example.

Once the activity is published and sent, the client receives a notification about a received assignment via their coaching app (mobile or desktop) or email.

The client can then open the Quenza software and find the new homework under their ‘To Do’ list.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Quenza provides the ability to create your own assignments as well as a wide selection of existing ones that can be assigned to clients for completion as homework.

The following activities can be tailored to meet specific needs or used as-is. Therapists can share them with the client individually or packaged into dedicated pathways.

Such flexibility allows therapists to meet the specific needs of the client using a series of dedicated and trackable homework.

Examples of Quenza’s ready-to-use science-based activities include the following:

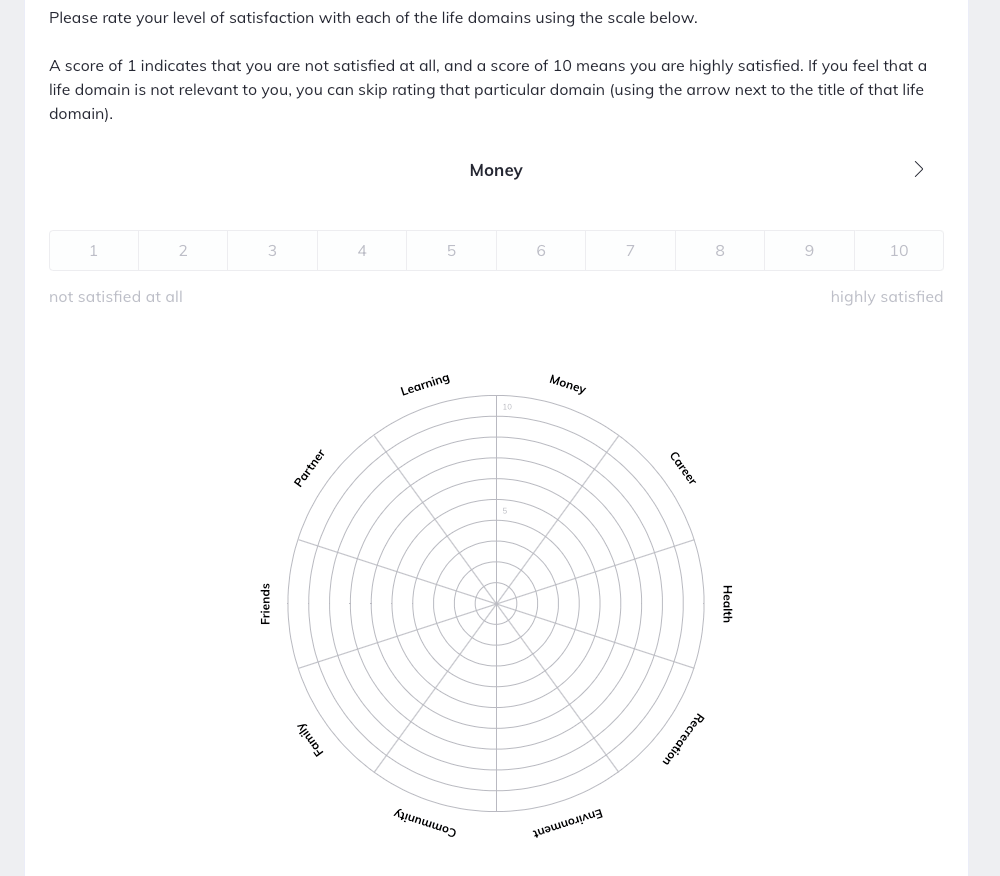

Wheel of Life

The Wheel of Life is a valuable tool for identifying and reflecting on a client’s satisfaction with life.

You can find the worksheet in the Positive Psychology Toolkit© , and it is also included in the Quenza library. The client scores themselves between 1 and 10 on specific life domains (the therapist can tailor the domains), including relationships, career development, and leisure time.

This is an active exercise to engage the client early on in therapy to reflect on their current and potential life. What is it like now? How could it look?

The wheel identifies where there are differences between perceived balance and reality .

The deep insights it provides can provide valuable input and prioritization for goal setting.

The Private Garden: A Visualization for Stress Reduction

While stress is a normal part of life, it can become debilitating and interfere with our everyday lives, stopping us from reaching our life goals.

We may notice stress as worry, anxiety, and tension and resort to avoidant or harmful behaviors (e.g., abusing alcohol, smoking, comfort eating) to manage these feelings.

Visualization is simple but a powerful method for reducing physical and mental stress, especially when accompanied by breathing exercises.

The audio included within this assignment helps the listener visualize a place of safety and peace and provides a temporary respite from stressful situations.

20 Guidelines for Developing a Growth Mindset

Research into neuroplasticity has confirmed the ability of the adult brain to continue to change in adulthood and the corresponding capacity for people to develop and transform their mindsets (Dweck, 2017).

The 20 guidelines (included in our Toolkit and part of the Quenza library) and accompanying video explain our ability to change mentally and develop a growth mindset that includes accepting imperfection, leaning into challenges, continuing to learn, and seeing ‘failure’ as an opportunity for growth.

Adopting a growth mindset can help clients understand that our abilities and understanding are not fixed; we can develop them in ways we want with time and effort.

Self-Contract

Committing to change is accepted as an effective way to promote behavioral change – in health and beyond. When a client makes a contract with themselves, they explicitly state their intention to deliver on plans and short- and long-term goals.

Completing and signing such a self-contract (included in our Toolkit and part of the Quenza library) online can help people act on their commitment through recognizing and living by their values.

Not only that, the contract between the client and themselves can be motivational, building momentum and self-efficacy.

The contract can be automatically personalized to include the client’s name but also manually reworded as appropriate.

The client completes the form by restating their name and committing to a defined goal by a particular date, along with their reasons for doing so.

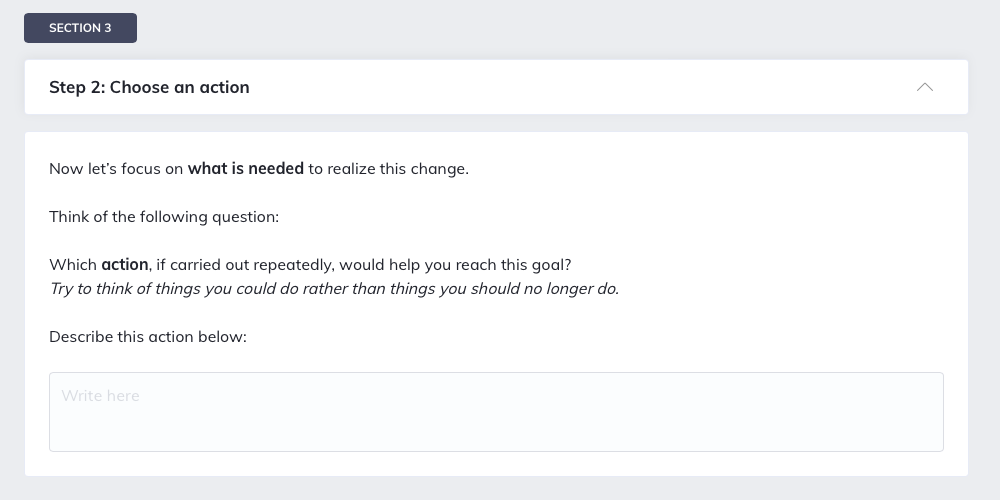

Realizing Long-Lasting Change by Setting Process Goals

We can help clients realize their goals by building supportive habits. Process goals – for example, eating healthily and exercising – require ongoing actions to be performed regularly.

Process goals (unlike end-state goals, such as saving up for a vacation) require long-lasting and continuous change that involves monitoring standards.

This tool (included in our Toolkit and part of the Quenza library) can help clients identify positive actions (rather than things to avoid) that they must carry out repeatedly to realize change.

We have many activities that can be used to help clients attending therapy for a wide variety of issues.

In this section, we consider homework ideas that can be used in couples therapy, family therapy, and supporting clients with depression and anxiety.

Couples therapy homework

Conflict is inevitable in most long-term relationships. Everyone has their idiosyncrasies and individual set of needs. The Marital Conflicts worksheet captures a list of situations in which conflicts arise, when they happen, and how clients feel when they are (un)resolved.

Family therapy homework

Families, like individuals, are susceptible to times of stress and disruptions because of life changes such as illness, caring for others, and job and financial insecurity.

Mind the Gap is a family therapy worksheet where a family makes decisions together to align with goals they aspire to. Mind the gap is a short exercise to align with values and improve engagement.

How holistic therapist Jelisa Glanton uses Quenza

Homework ideas for depression and anxiety: 3 Exercises

The following exercises are all valuable for helping clients with the effects of anxiety and depression.

Activity Schedule is a template assisting a client with scheduling and managing normal daily activities, especially important for those battling with depression.

Activity Menu is a related worksheet, allowing someone with depression to select from a range of normal activities and ideas, and add these to a schedule as goals for improvement.

The Pleasurable Activity Journal focus on activities the client used to find enjoyable. Feelings regarding these activities are journaled, to track recovery progress.

Practicing mindfulness is helpful for those experiencing depression (Shapiro, 2020). A regular gratitude practice can develop new neural pathways and create a more grateful, mindful disposition (Shapiro, 2020).

Each activity can be tailored to the client’s needs; shared as standalone exercises, worksheets, or questionnaires; or included within a care pathway.

A pathway is an automated and scheduled series of activities that can take the client through several stages of growth, including psychoeducation , assessment, and action to produce a behavioral change in a single journey.

How to build pathways

The creator can add two pathway titles. The second title is not necessary, but if entered, it is seen by the client in place of the first.

Once named, a series of steps can be created and reordered at any time, each containing an activity. Activities can be built from scratch, modified from existing ones in the library, or inserted as-is.

New activities can be created and used solely in this pathway or made available for others. They can contain various features, including long- and short-answer boxes, text boxes, multiple choice boxes, pictures, diagrams, and audio and video files.

Quenza can automatically deliver each step or activity in the pathway to the client following the previous one or after a certain number of days. Such timing is beneficial when the client needs to reflect on something before completing the next step.

Practitioners can also designate steps as required or optional before the client continues to the next one.

Practitioners can also add helpful notes not visible to the client. These comments can contain practical reminders of future changes or references to associated literature that the client does not need to see.

It is also possible to choose who can see client responses: the client and you, the client only, or the client decides.

Tags help categorize the pathway (e.g., by function, intended audience, or suggested timing within therapy) and can be used to filter what is displayed on the therapist’s pathway screen.

Once designed, the pathway can be saved as a draft or published and sent to the client. The client receives the notification of the new assignment either via email or the coaching app on their phone, tablet, or desktop.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Success in therapy is heavily reliant on homework completion. The greater the compliance, the more likely the client is to have a better treatment outcome (Mausbach et al., 2010).

To improve the likelihood that clients engage with and complete the assignments provided, homework must be appropriate to their needs, have a sound rationale, and do the job intended (Beck, 2011).

Technology such as Quenza can make homework readily available on any device, anytime, from any location, and ensure it contains clear and concise psychoeducation and instructions for completion.

The therapist can easily create, copy, and tailor homework and, if necessary, combine multiple activities into single pathways. These are then shared with the click of a button. The client is immediately notified but can complete it at a time appropriate to them.

Quenza can also send automatic reminders about incomplete assignments to the client and highlight their status to the therapist. Not only that, but any resulting questions can be delivered securely to the therapist with no risk of getting lost in a busy email inbox.

Why not try the Quenza application? Try using some of the existing science-based activities or create your own. It offers an impressive array of functionality that will not only help you scale your business, but also ensure proactive, regular communication with your existing clients.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond . Guilford Press.

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Robinson.

- Mausbach, B. T., Moore, R., Roesch, S., Cardenas, V., & Patterson, T. L. (2010). The relationship between homework compliance and therapy outcomes: An updated meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research , 34 (5), 429–438.

- Ribbers, A., & Waringa, A. (2015). E-coaching: Theory and practice for a new online approach to coaching . Routledge.

- Shapiro, S. L. (2020). Rewire your mind: Discover the science and practice of mindfulness. Aster.

- Tang, W., & Kreindler, D. (2017). Supporting homework compliance in cognitive behavioural therapy: Essential features of mobile apps. JMIR Mental Health , 4 (2).

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Empty Chair Technique: How It Can Help Your Clients

Resolving ‘unfinished business’ is often an essential part of counseling. If left unresolved, it can contribute to depression, anxiety, and mental ill-health while damaging existing [...]

29 Best Group Therapy Activities for Supporting Adults

As humans, we are social creatures with personal histories based on the various groups that make up our lives. Childhood begins with a family of [...]

47 Free Therapy Resources to Help Kick-Start Your New Practice

Setting up a private practice in psychotherapy brings several challenges, including a considerable investment of time and money. You can reduce risks early on by [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (2)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (47)

- Resilience & Coping (35)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (30)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Shortform Books

The World's Best Book Summaries

Assigning CBT Homework: Tips for Therapists

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond" by Judith S. Beck. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What tips can help you assign CBT homework to your patients? What are some examples of cbt homework tasks? How can you improve the completion rate?

Assigning homework during a CBT session can improve patient progress dramatically. It gives the patient a chance to practice what they have learned during the therapy session. Learning how to assign CBT homework successfully and improve completion rate will help your patient achieve their goals.

Keep reading for tips about assigning CBT homework.

CBT Homework Assignments