- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Case Study in Education Research

Introduction, general overview and foundational texts of the late 20th century.

- Conceptualisations and Definitions of Case Study

- Case Study and Theoretical Grounding

- Choosing Cases

- Methodology, Method, Genre, or Approach

- Case Study: Quality and Generalizability

- Multiple Case Studies

- Exemplary Case Studies and Example Case Studies

- Criticism, Defense, and Debate around Case Study

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Program Evaluation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Case Study in Education Research by Lorna Hamilton LAST REVIEWED: 21 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 June 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0201

It is important to distinguish between case study as a teaching methodology and case study as an approach, genre, or method in educational research. The use of case study as teaching method highlights the ways in which the essential qualities of the case—richness of real-world data and lived experiences—can help learners gain insights into a different world and can bring learning to life. The use of case study in this way has been around for about a hundred years or more. Case study use in educational research, meanwhile, emerged particularly strongly in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States as a means of harnessing the richness and depth of understanding of individuals, groups, and institutions; their beliefs and perceptions; their interactions; and their challenges and issues. Writers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, advocated the use of case study as a form that teacher-researchers could use as they focused on the richness and intensity of their own practices. In addition, academic writers and postgraduate students embraced case study as a means of providing structure and depth to educational projects. However, as educational research has developed, so has debate on the quality and usefulness of case study as well as the problems surrounding the lack of generalizability when dealing with single or even multiple cases. The question of how to define and support case study work has formed the basis for innumerable books and discursive articles, starting with Robert Yin’s original book on case study ( Yin 1984 , cited under General Overview and Foundational Texts of the Late 20th Century ) to the myriad authors who attempt to bring something new to the realm of case study in educational research in the 21st century.

This section briefly considers the ways in which case study research has developed over the last forty to fifty years in educational research usage and reflects on whether the field has finally come of age, respected by creators and consumers of research. Case study has its roots in anthropological studies in which a strong ethnographic approach to the study of peoples and culture encouraged researchers to identify and investigate key individuals and groups by trying to understand the lived world of such people from their points of view. Although ethnography has emphasized the role of researcher as immersive and engaged with the lived world of participants via participant observation, evolving approaches to case study in education has been about the richness and depth of understanding that can be gained through involvement in the case by drawing on diverse perspectives and diverse forms of data collection. Embracing case study as a means of entering these lived worlds in educational research projects, was encouraged in the 1970s and 1980s by researchers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, who provided a helpful impetus for case study work in education ( Stenhouse 1980 ). Stenhouse wrestled with the use of case study as ethnography because ethnographers traditionally had been unfamiliar with the peoples they were investigating, whereas educational researchers often worked in situations that were inherently familiar. Stenhouse also emphasized the need for evidence of rigorous processes and decisions in order to encourage robust practice and accountability to the wider field by allowing others to judge the quality of work through transparency of processes. Yin 1984 , the first book focused wholly on case study in research, gave a brief and basic outline of case study and associated practices. Various authors followed this approach, striving to engage more deeply in the significance of case study in the social sciences. Key among these are Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 , along with Yin 1984 , who established powerful groundings for case study work. Additionally, evidence of the increasing popularity of case study can be found in a broad range of generic research methods texts, but these often do not have much scope for the extensive discussion of case study found in case study–specific books. Yin’s books and numerous editions provide a developing or evolving notion of case study with more detailed accounts of the possible purposes of case study, followed by Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 who wrestled with alternative ways of looking at purposes and the positioning of case study within potential disciplinary modes. The authors referenced in this section are often characterized as the foundational authors on this subject and may have published various editions of their work, cited elsewhere in this article, based on their shifting ideas or emphases.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This is Merriam’s initial text on case study and is eminently accessible. The author establishes and reinforces various key features of case study; demonstrates support for positioning the case within a subject domain, e.g., psychology, sociology, etc.; and further shapes the case according to its purpose or intent.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stake is a very readable author, accessible and yet engaging with complex topics. The author establishes his key forms of case study: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Stake brings the reader through the process of conceptualizing the case, carrying it out, and analyzing the data. The author uses authentic examples to help readers understand and appreciate the nuances of an interpretive approach to case study.

Stenhouse, L. 1980. The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal 6:1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/0141192800060101

A key article in which Stenhouse sets out his stand on case study work. Those interested in the evolution of case study use in educational research should consider this article and the insights given.

Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE.

This preliminary text from Yin was very basic. However, it may be of interest in comparison with later books because Yin shows the ways in which case study as an approach or method in research has evolved in relation to detailed discussions of purpose, as well as the practicalities of working through the research process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, affective learning in digital education—case studies of social networking systems, games for learning, and digital fabrication.

- Faculty of Education, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

Technological innovations, such as social networking systems, games for learning, and digital fabrication, are extending learning and interaction opportunities of people in educational and professional contexts. These technological transformations have the ability to deepen, enrich, and adaptively guide learning and interaction, but they also hold potential risks for neglecting people's affective learning processes—that is, learners' emotional experiences and expressions in learning. We argue that technologies and their usage in particular should be designed with the goal of enhancing learning and interaction that acknowledges both fundamental aspects of learning: cognitive and affective. In our empirical research, we have explored the possibility of using various types of emerging digital tools as individual and group support for cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning. We present four case studies of experiments dealing with social networking systems, programming with computer games, and “makers culture” and digital fabrication as examples of digital education. All these experiments investigate novel ways of technological integration in learning by focusing on their affective potential. In the first study, a social networking system was used in a higher education context for providing a forum for online learning. The second study demonstrates a Minecraft experiment as game-based learning in primary school education. Finally, the third and the fourth case study showcases examples of “maker” contexts and digital fabrication in early education and in secondary school. It is concluded that digital systems and tools can provide multiple opportunities for affective learning in different contexts within different age groups. As a pedagogical implication, scaffolding in both cognitive and affective learning processes is necessary in order to make the learning experience with emerging digital tools meaningful and engaging.

Introduction

Current technological transformations in society bring new abilities for sensing, adapting, and providing information to users within their environments ( Laru et al., 2015 ; Chang et al., 2018 ; Huang et al., 2019 ). This can, for example, deepen, enrich, and guide educational and professional interactions ( Rummel, 2018 ; Stracke and Tan, 2018 ). Technologies have already been used to improve participants' cognitive learning experiences, to create efficient and constructive communication, and to effectively use shared resources, as well as to find and build groups and communities ( Jeong and Hmelo-Silver, 2016 ).

However, research has also shown that technology can alter social interactions. For instance, technology can affect the self-disclosure and identity management of individuals ( Yee and Bailenson, 2007 ) as well as provide an arena for bullying (Santiago and Siklander, in review), thus running the risk of inhibiting productive social interactions or providing less than optimal support for them. In terms of group interactions and technologically enhanced collaborations in particular, challenges may relate to a cognitive load too excessive to efficiently handle content and task related activities simultaneously with social and technological factors ( Bruyckere et al., 2015 ; May and Elder, 2018 ; Pedro et al., 2018 ) or the lack of available important social cues for social information processing, particularly in text-based communications ( Kreijns et al., 2003 ; Walther, 2011 ; Terry and Cain, 2016 ). This discussion of technology's challenges is particularly relevant in bigger online learning communities and social networking systems, but also in small group collaboration ( Bodemer and Dehler, 2011 ; Davis, 2016 ), such as in the context of games for learning, digital fabrication, and “maker” education.

Social networking systems, games for learning, and digital fabrication (making) will be further examined in this paper with case study examples. These case examples are chosen with regard to their likely impact on learning and instruction in current and future educational designs ( Woolf, 2010 ; Chang et al., 2018 ; Huang et al., 2019 ). One of the main challenges that teachers face in the context of adopting contemporary technologies to support learning activities is the fact that professional knowledge and competencies are needed in both technology and pedagogy ( Valtonen et al., 2019 ). This means that in addition to technical aspects, it is important that teachers understand and consider the basic processes of how people learn as an individual and as part of collaborative group ( Häkkinen et al., 2017 ). Therefore, it is essential to explore and characterize learning and interaction processes, including cognitive and affective components, when digital tools and learning environments are implemented in educational contexts.

This paper is grounded in the premise that technologies should enhance the cognitive and affective learning processes in collaboration. Emotional experiences and expressions are recognized as an especially central part of successful collaborative learning ( Baker et al., 2013 ). The use of potential technological enhancements in collaboration necessitates an interdisciplinary understanding of the social factors and emotional dynamics influencing the learning and interaction processes. We argue that when the affective interactions are more thoroughly accounted for and enhanced through technology, they can have positive implications for cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful collaborations, thus contributing to better competence building, social equity, and participation in group workings ( Järvenoja and Järvelä, 2013 ; Isohätälä et al., 2017 ; Järvenoja et al., 2018 ).

Collaborative Learning as a Cognitive and Affective Learning Process

Collaborative learning is a specific type of learning and interaction process in which learners in a group share their overall learning process by negotiating their goals for learning and coordinating their mutual learning processes together ( Roschelle and Teasley, 1995 ). Since the process of collaborative learning consists of discussions, negotiations, and reflections on the task at hand, it has the potential to lead to deeper information processing than individuals would achieve alone ( Dillenbourg, 1999 ; Baker, 2015 ). The premise for successful collaborative learning is that group members are actively engaged in building, monitoring, and maintaining their shared learning processes on cognitive and affective levels ( Barron, 2003 ; Näykki et al., 2017b ; Isohätälä et al., 2019a ). This means that interpreting and understanding who you are working with, what is being worked on, and how your actions and emotions affect others is essential to obtain successful collaborative learning ( Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2011 ; Miyake and Kirschner, 2014 ). We follow the conceptualization that views successful collaborative learning as a combination of an outcome (deeper understanding and developed individual and group learning skills), and an experience (a student's own evaluation and interpretation of how [s]he succeeded) ( Baker, 2015 ).

In general, affective processes play an important role in individuals' learning as well as in groups' learning and interaction processes ( Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2011 ; Järvenoja et al., 2015 ; Polo et al., 2016 ; Isohätälä et al., 2019b ). Students' emotions, such as enjoyment, boredom, pride, and anxiety, are seen to affect achievement by influencing their involvement and attitude toward learning and learning environments (e.g., Pekrun et al., 2002 ; Boekaerts, 2003 , 2011 ; Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012 ). These emotional experiences naturally have a great effect on how students and/or groups work on their task assignments. In our research, we have been particularly interested in the role of emotions as a part of groups' coordinated learning processes—how group members experience emotions and how they express their emotions in order to maintain and restore (when needed) a socio-emotionally secure atmosphere for learning and collaboration ( Näykki et al., 2014 ). This has been done by observing student groups' interaction processes to understand how emotions are expressed, reflected, and shaped by social interaction ( Baker et al., 2013 ; Isohätälä et al., 2017 ; Näykki et al., 2017a ).

We ground this study in the increasing empirical understanding of the multifaceted interaction processes involved in collaborative learning, integrating cognitive, and affective components as the core of collaboration ( Volet et al., 2009 ; Järvel et al., 2010 , 2013 ; Näykki et al., 2014 ; Ucan and Webb, 2015 ; Sobocinski et al., 2016 ; Isohätälä et al., 2019a ; Vuopala et al., 2019 ). In theory, collaborative learning requires group members to be aware of and to coordinate with their cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and emotional resources and efforts ( Hadwin et al., 2018 ). In practice, this involves students sharing their thinking and understanding, as well as showing verbally and behaviorally their commitment to the task and to the group ( Järvelä et al., 2016 ; Isohätälä et al., 2017 ).

How to Enhance Opportunities for Cognitive and Affective Learning Processes With Pedagogical Designs and Digital Tools

Prior research has suggested that students need a scaffolding to engage with and progress in active and effective collaborative learning ( Kirschner et al., 2006 ; Belland et al., 2013 ). In order to favor the emergence of productive interactions and thus to improve the quality of collaborative learning, different pedagogical models, and design approaches have been developed in collaborative learning research ( Hämäläinen and Häkkinen, 2010 ). One example of a strategy to enhance the process of collaboration is to structure learners' actions with the aid of scripted cooperation ( Fischer et al., 2013 ). Scripting is defined as “a set of instructions prescribing how students should perform in groups, how they should interact and collaborate and how they should solve the problem” ( Dillenbourg, 2002 , p. 63). In other words, scripts support collaborative processes by specifying, sequencing, and distributing the activities that learners are expected to engage in during collaboration ( Dillenbourg, 2002 ; Kollar et al., 2006 ). Scripts typically aim to smooth coordination and communication, but there are also scripts that aim to promote high-level socio-cognitive activities—e.g., explaining, arguing, and question asking ( Weinberger et al., 2005 ; Fischer et al., 2013 ; Tsovaltzi et al., 2017 )—or acknowledge and promote socio-emotional activities ( Näykki et al., 2017a ).

In addition to designing certain learning activities with the scripting approach, previous research in the field of technologically enhanced learning has demonstrated how technology can function as a tool for individuals' and groups' learning, allowing meaningful learning interactions to occur ( Jeong and Hmelo-Silver, 2016 ; Rosé et al., 2019 ). Recently, more generic digital tools such as social networking tools, games, or mobile phones have been increasingly popular among educators and instructional designers ( Ludvigsen and Mørch, 2010 ; Laru et al., 2015 ). Such tools are being progressively more used in educational contexts but are not usually specifically designed to help students to engage in cognitively effortful interaction such as problem solving, collaborative knowledge construction, or inquiry learning ( Gerjets and Hesse, 2004 ). Nor are these tools often designed for affectively meaningful interactions such as expression and reflection of emotional experiences ( Jones and Issroff, 2005 ; Jeong and Hmelo-Silver, 2016 ).

Altogether, these tools rarely offer specific instructional guidance concerning collaborative learning ( Kirschner et al., 2006 ). Instead, both generic and specific cognitive tools ( Kim and Reeves, 2007 ) typically provide an open problem space, where learners are left to their own devices. In such spaces, learners are free to choose (a) what activities to engage in with respect to the problem at hand and (b) how they want to perform those activities ( Kollar et al., 2007 ). Modern social networking systems, games for learning, and contexts for digital fabrication and making can be categorized into open problem spaces where learning is often supported without tightly structured socio-technological instructional design ( Laru et al., 2015 ; Hira and Hynes, 2018 ).

Case Examples in Digital Education

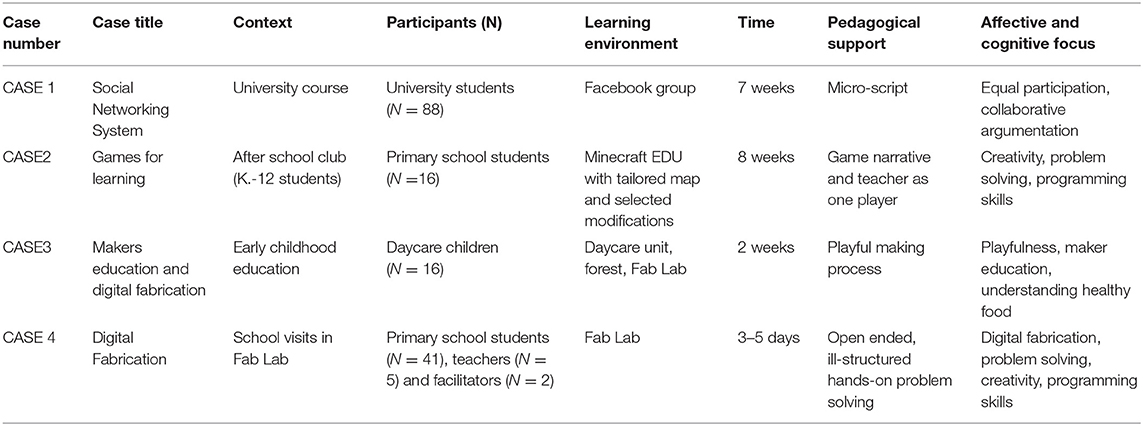

We present and explore four cases ( Table 1 ) involving social networking systems, games for learning, and digital fabrication where emergent and contemporary technologies are used to support collaborative learning in open problem spaces, especially focusing on cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning in groups. These emergent digital tools, with their respective socio-technical designs, were selected because they each represent different ways to provide opportunities for affective learning—for experiencing and expressing emotions as well as for supporting equal participation and a safe group atmosphere (cf. Baker et al., 2013 ). Traditionally all these technologies and activities have mainly been present in informal contexts as associated with social lives of the users, and thus, it can be assumed that this is one reason why they are able to access emotions in powerful ways. These technologies also hold the potential for learning in formal education as well, as a part of learning activities organized by educational institutions ( Pedro et al., 2018 ).

Table 1 . Summary of the case examples: social networking systems, games for learning, maker education, and digital fabrication.

CASE 1: Social Networking Systems for Supporting Equal Participation and Collaborative Argumentation

Social Networking Sites (SNS), such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, are widely used communication platforms worldwide because of easy access and unrestricted interactivity ( Bowman and Akcaoglu, 2014 ). They are mostly used for informal, everyday communication, but these platforms also offer possibilities to education by allowing idea sharing and a knowledge co-construction process ( Laru et al., 2012 ; Vuopala et al., 2016 ; Tsovaltzi et al., 2017 ) where learners are interacting and building new frameworks to extend the knowledge and understanding of each individual student ( Janssen et al., 2012 ). These productive interactional processes include sharing ideas, negotiating, asking thought-provoking questions, and providing justified arguments ( Vuopala et al., 2016 ). Studies have also shown that the use of SNS can be beneficial for learning purposes by, for example, fostering affective interactions in academic life, allowing students to share emotional experiences, and providing support for socio-emotional presence ( Pempek et al., 2009 ; Bennett, 2010 ; Ryan et al., 2011 ; Wodzicki et al., 2012 ; Bowman and Akcaoglu, 2014 ).

However, previous studies have proven that in SNS the level of knowledge co-construction and argumentation is often superficial, lacking solid arguments as well as affective interaction ( Bull et al., 2008 ; Dabbagh and Reo, 2011 ). Engaging in these cognitive and affective processes is not necessarily spontaneous, therefore, it is essential to support students' learning processes. One way to promote productive collaborative learning is through the use of pedagogical scripts that have been used for guiding learners to engage both in knowledge co-construction and in affective processes ( Dillenbourg, 2002 ; King, 2007 ; Fischer et al., 2013 ; Näykki et al., 2017a ; Wang et al., 2017 ).

This case study presents research in which Facebook was used as a platform for argumentation. Higher education students ( N = 88) from one German and two Finnish universities participated in a seven week long online course named “CSCL, Computer Supported Collaborative Learning” ( Puhl et al., 2017 ). The course included the following learning topics: scripting, motivation and emotions, and metacognition. Students worked in ten groups with four participants in each. The first phase of the course was orientation and introduction (1 week). The main aim of the orientation week was to allow group members to meet each other (online) and to create a safe group atmosphere. After the orientation phase, each small group had a 2 week period to discuss each presented topic (overall, 6 weeks) in their own closed Facebook group.

Small group collaboration was supported with a micro-script ( Weinberger et al., 2007 ; Noroozi et al., 2012 ), which guided learners into knowledge co-construction and argumentation. The study was particularly focused on exploring how different preassigned roles and sentence openers supported argumentation ( Weinberger et al., 2010 ) and contributed to the groups' affective interactions especially by encouraging students to participate equally and motivating the group atmosphere. The roles given to each student were especially designed to prompt not only productive argumentation but also socio-emotional processes. The roles assigned to the students were: captain (motivated the group members' participation), contributor (identified and elaborated pro-arguments), critic (identified and elaborated counter-arguments), and composer (constructed a synthesis of the pro- and counter-arguments). To support their enactment of the named role, the students were given specific sentence openers, such as: “Have you all understood what is meant by…” (captain), “My claim is…” (contributor), “Here is a different claim I think needs to be taken into account …” (critic) and “To combine previously mentioned perspectives it can be concluded…” (composer). The script was faded out as the course proceeded. During the first 2 weeks, both the roles as well as the sentence openers were used to guide productive collaboration. Next, only the roles were given as a script, without sentence openers. However, students got a different role compared to the first week. And after that, the whole script was faded out; it was expected that, by that time, the learners had internalized the script and were thus able to interact purposefully without external support ( Wecker and Fischer, 2011 ; Noroozi et al., 2017 ).

To reach an understanding of how the students interacted during the course, all discussion notes on Facebook were analyzed ( Puhl et al., 2017 ). This was done by categorizing the discussion notes according to their transactivity to the following categories: quick consensus building, integration-oriented consensus building and conflict-oriented consensus building and in terms of their epistemic dimension: coordination, own explanation, misconception, learning content ( Weinberger and Fischer, 2006 ). In general, students participated equally in the joint discussions according to the roles given to them, but the actual use of the sentence openers was more random. The main results indicated that, with this design, students engaged actively in argumentative knowledge co-construction, and that there were no significant differences in terms of the amount of activity between the differently scripted studying phases. All the assigned roles were treated as equally important in terms of both cognitive and affective aspects of learning even though they promoted different aspects of socio-emotional processes. However, during the course it came clear that the role of captain was especially crucial in promoting a good group atmosphere and keeping the motivation level high. The following examples from group discussions illustrate the captain's contributions:

“Thanks for your comments. These are all interesting thoughts. I agree with you that there is not a ‘one fits for all' solution. While regarding thought on ‘obligation’, well I agree that there is that component as well in any learning situation.”

“If you have some questions while you are reading, if something is unclear or something is just interesting, I'd like to encourage you to post something into the group that we can talk about it. So, enjoy the rest of your weekend and have a nice week.”

These examples illustrate how the captain encouraged group members to participate in joint discussions by giving positive feedback, and by making suggestions how to proceed. The results showed that the roles functioned also for affective level learning by, for example, managing the discourse, inducing conflicts through pro- and counter-arguments, and resolving the conflicts by bringing the different perspectives together. To conclude, in this case example, the roles assisted equal participation, feelings of belonging, and good working relationships between learners. The students' interaction was supportive, and arguments were well-structured. Furthermore, roles kept the discussion on task and there was no confusion about the responsibilities ( Bruyckere et al., 2015 ; May and Elder, 2018 ; Pedro et al., 2018 ).

This example of Facebook as a SNS shows how an actively used “everyday digital tool” provided easy access to and a familiar platform for productive collaborative learning. While students used Facebook regularly for informal communication, they actively followed study-related discussions at the same time. It was obvious that in this case informal and formal communication and collaboration supported each other. The students in this study were asked to follow a specific micro-script, and thus their opportunities for designing their own learning activities were rather limited. Another way to integrate informal and formal education and to provide more open opportunities for creative thinking and problem solving is the use of games for learning, as will be described in the following example.

CASE 2: Games for Learning as Supporting Students' Creativity, Problem Solving, and Programming Skills

Currently, there is an increasing interest in implementing games in an educational context ( Nebel et al., 2016 ; Qian and Clark, 2016 ). Connolly et al. (2012) found in their systematic literature review that playing computer games is linked to a range of perceptual, cognitive, behavioral, affective, and motivational impacts and outcomes. However, previous studies have shown that the game environment itself does not guarantee deep learning and meaningful learning experiences ( Lye and Koh, 2014 ; Mayer, 2015 ). The challenge is that many educational games follow simple designs that are only narrowly focused on academic content and provide drill and practice methods similar to worksheets or stress memorization of facts ( Qian and Clark, 2016 ).

Careful pedagogical design is needed in order to implement an educational game environment as a holistic problem-solving environment. For example, game design elements can provide opportunities for learners' self-expression, discovery, and control. These types of playing activities can create a learning environment that supports students' cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning, for example in terms of programming skills, creativity, problem solving ( Kazimoglu et al., 2012 ; Qian and Clark, 2016 ), and motivational engagement ( Bayliss, 2012 ; Zorn et al., 2013 ; Pellas, 2014 ).

This study was designed to integrate informal and formal learning activities for students in the context of an after-school Minecraft club. Minecraft is a multiplayer sandbox game designed around breaking and placing blocks. Unlike many other games, when played in its traditional settings, Minecraft does allow players the freedom to immerse themselves into their own narrative: to build, create, and explore. Minecraft, along with modification software (“mods”), has the tools for teaching and learning programming ( Zorn et al., 2013 ; Risberg, 2015 ; Nebel et al., 2016 ).

The participants in this case study were primary school students ( N = 16, 11 boys, 5 girls, 11 years old) who participated in the after-school Minecraft club ( Ruotsalainen et al., 2020 ). The club included eight 90-min sessions of face-to-face meetings as well as unlimited collaboration time in the virtual space between the meetings. Minecraft gameplay was based on a storyline wherein pirates tried to survive after a shipwreck, escape, and expand their territories to other islands. To be able to escape from the island, several main quests (tasks) had to be solved: tutorial (weeks 1–2), electrical power (week 3), area and volume calculations (week 4), survival of zombie apocalypse (week 5), European flags (week 6), programming (week 7), and a final meeting (week 8). The majority of these quests were ill-structured and challenging problems. Therefore, the designed structure included repetitive pedagogical phases with teacher scaffolding (described below), but also full access to all content at any time (but not guided and explained).

Each week followed a similar structure:

a) Introduction (club meeting), a basic introduction to the session's theme.

b) Guided in-game tour (club meeting) where the respective main quest was presented, trained, and materials were distributed. The Captain (teacher) provided scaffolding for pirate students.

c) Main Quest (club meeting; between meetings, students performed task(s), e.g., building structures or coding).

d) Reflection (club meeting), a group discussion at the end of each session to reflect on task design and game experiences.

e) Free to Play (gameplay between meetings), the phase where students were able to continue their existing activities or explore the game on their own.

f) Captain's Quest (gameplay between meetings), which was similar to the main quest, but tasks were voluntary for students.

g) Presentation(s) for Rewards (next club meeting), an activity where students presented what they had done in the main quest and the Captain's quest. After successfully completing quests, student pirates received rewards in the form of Minecraft objects. Without rewards, student pirates were not able to survive, form society on the island, build better houses, or complete (“win”) the game.

The tools that were designed for the club were the Minecraft game, island map, and three Minecraft modifications ( Figure 1 ). The game map was designed to include problem-based puzzles (quests) and a narrative about escaping from the deserted island after a shipwreck. Modifications enabled teachers to change Minecraft's 18 game rules, alter game content, redesign textures, and give players new abilities within the game ( Kuhn and Dikkers, 2015 ). While the island map provided context for game narrative and gameplay itself, modifications worked as an engine, which enabled real electrical power simulation (ElectricalAge), programming (ComputerCraft), and easy redesign of the learning experiences (WorldEdit) during the game. The three major structures were: a deserted island with a sunken ship (home for the students' characters), the hall of quests, which was a building on the island (main quests were presented here), and the science center located outside of the island (a place with free access to formal lessons and informal training). Collaborative learning was regarded as a fundamental element of the activity in Minecraft gameplay. Therefore, many structural elements were designed to support collaborative game experience; for example, border blocks forced students' avatars to live in a small area next to each other. However, there were no detailed structures or scaffolds designed as a support for collaboration. Students were inhabitants of the Minecraft world, where collaboration is necessary to survive. The following example explains how one student described his/her experienced reasons for collaboration in an interview that were conducted right after the each face to face meeting. In this example one student describes his actions in the main quest “survival of zombie apocalypse.”

“We all came together at the ‘hall of quests’, it was safe and we had time to make up a plan together since there were no zombies. All players were here and we discussed what to do to survive. Most of my friends helped me and I helped them to survive. We had to trust each other, to survive you do teamwork.”

Figure 1. (A) Island at the start of the game when students' ship has wrecked. (B) Island after students have created their society (game activity between club meetings, Captain's quests). (C) Hall of quests, which was the place for information sharing, reflection, and teleportation to the science center. (D) Science center (main quests were played here) with a view into the coding quest.

Overall, the Minecraft game in this study was designed so that knowledge acquisition was prompted (e.g., about electricity), skill acquisition was supported (e.g., programming and collaboration), and affective and motivational outcomes were rewarded (e.g., strategies to accomplish quests and reflections during the meetings). Degrees of freedom guaranteed that the original constructionist gameplay was available for more advanced players, which was needed to avoid frustration or domination during the game ( Connolly et al., 2012 ; Nebel et al., 2016 ). The students underlined in an interview how emotional the game playing experience was for them: “I usually do not really like these guys, but I am kind of sad that this experiment is over. I'm going to miss our village and society a lot. I am pretty sure I won't speak to half of the players anymore.”

To conclude, Minecraft is an example of a constructivist gaming experience in which players can play, modify the game, or even create their own games for learning ( Kafai and Burke, 2015 ). In this case study, the students modified the game. This type of gaming approach has a strong pedagogical connection with another contemporary digital education phenomena: “maker's culture,” making and digital fabrication. While Minecraft is about a block-based world of “digital making,” digital fabrication and making enables learners to design their own artifacts in the situated (unstructured and open-ended) problem solving contexts.

CASE 3: Digital Fabrication and Makers Education for Supporting Collaborative Learning

Making is a central concept in the maker education approach. In practice, making is “a class of activities focused on designing, building, modifying, and/or repurposing material objects, for playing or useful ends, oriented toward making a ‘product' that can be used, interact with, or demonstrated” ( Martin, 2015 , p. 31). Digital fabrication is a concept in parallel with making that is commonly used to describe a process of making physical objects by utilizing digital tools for designing. Digital fabrication activities can be conducted in the context of Fab Lab, that is, a technical prototyping platform “comprised of off-the-shelf, industrial-grade fabrication and electronics tools, wrapped in open source software” ( Fab Foundation, n.d. ).

The basic idea of maker culture and digital fabrication places the learner firmly at the center of the learning process with a focus on a connection to real-world issues and meaningful problems. In the context of digital fabrication and Fab Labs, complex, undefined, open-ended, and unstructured problem-solving activities are typical ( Halverson and Sheridan, 2014 ; Chan and Blikstein, 2018 ). Prior studies in educational contexts have found that maker culture activities hold great potential for developing a sense of personal agency, improving self-efficacy and self-esteem, and supporting learners in becoming an active member of a learning community ( Halverson and Sheridan, 2014 ; Chu et al., 2017 ; Hira and Hynes, 2018 ). Taylor (2016) has concluded that the activities in “makerspaces” can be transformed into classroom projects that match the goals of twenty-first-century education. In other words, the overall learning experience through making can be empowering and can nurture students' creativity and inventiveness among other twenty-first-century skills ( Blikstein, 2013 ; Iwata et al., 2019 ; Pitkänen et al., 2019 ).

This case study presents research that was conducted in an early education context ( Siklander et al., 2019 ). Four to 5 year-old children ( N = 16) took part in the making process in indoor and outdoor making environments: kindergarten, a forest, and Fab Lab facilities at the university ( https://www.oulu.fi/fablab/ ).

In this case study, a narrative was built about an owl, a hand puppet, who asked for the children's help. The topic for learning was healthy food, and the aim was that the children learn to identify healthy and unhealthy food and to create a healthy plate through making, playing, and discussions. The experiment followed the playful learning process ( Hyvönen, 2011 ; Hyvönen et al., 2016 ) and started with an orientation phase that aimed to support the children's activation of prior knowledge by creating a concept map about the topic of “good health.” In other words, the starting point for children's making activities was their own investigations of the concept and events closely connected with their living environments and personal experiences. After the orientation, the hand puppet owl asked for the children's assistance in creating a healthy plate. In the first making activity, children searched for and cut out figures representing healthy food and created a healthy plate by using the selected figures. Next, the owl asked the children to cook food in the nearby forest and to serve it to the forest animals. The children orienteered to the forest, collected items in accordance with the recipe, cooked the food, and laid the table on the ground. After feasting with the children, the owl asked children to feed all the forest animals. This challenging task requested children to prepare fabricated food.

The next phase of the experiment was conducted in the FabLab. The researchers' role ( Hyvönen, 2011 ) was to understand and support the children's cognitive, emotional, and social views on making activities, although the environment was technical, noisy, and adult sized. The aim was to provide an emotionally and physically safe atmosphere and to encourage children to interact, enjoy, and express themselves while working together. After using the different senses (e.g., the smell of burning wood diffusing from the laser cutter), and taking a look at the facilities, technological equipment, and displayed outcomes, the owl's request was discussed. First, a big plate out of plywood was laser cutted. Research assistants guided the activities, and they let each child test the steering device and press the buttons. The children watched the cutting process very intensely, and were delighted while the plate was done, wanting also to touch and smell it. Finally, each child chose his or her favorite Muumin character and laser cut it to take home.

The process ended with the elaboration phase, in which the photo-elicitation method was used ( Dockett et al., 2017 ) for reflecting on and discussing the entire process with the children. They chose photos which they felt were interesting and inspiring during the process; thus, these photos represent positive emotions. They chose photos taken from the forest trip and the FabLab activities. The most meaningful objects in the forest were the map, which facilitated orienteering, the recipe, which allowed them to find items and count them, and the fire, which they set for cooking. These elements combine affective and cognitive learning with physical actions. Children held the map each by each, and carefully looked at it and the path ahead ( Pictures 1 , 2 ).

Picture 1 . Children cooking according to the recipe. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all depicted children for the publication of these images.

Picture 2 . Children at the FabLab presenting their ideas for the owl, other children, and adults around. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all depicted children for the publication of these images.

The Fab Lab was regarded also as a meaningful makerspace. With its many technologies, it provided totally new experiences for the children. It was experienced as exciting and activated the children's collaboration, imagination, interest, and inspiration. During the experiment, the children's interaction was filled with humor and evolved in the process of thought bouncing.

In this case study, making activities and the playfulness of this process ( Hyvönen, 2011 ; Hyvönen et al., 2016 ) denoted affectivity in two ways: first, the process of making was designed to allow children to experience emotions such as curiosity, joy, agency, acceptance, and excitement, but also negative feelings such as impatience, frustration, and disappointment (see also Hyvönen and Kangas, 2007 ). Secondly, during the activities and interaction, children were able to learn to recognize, and regulate their emotions. This was evident particularly in collaborative situations when children had to wait their turns, or when they were together and excited to express their ideas. To conclude, it can be said that, for children, making is not a specific type of activity, but rather the natural way of playfully being and engaging in any activity, including their own emotions, other people, and playthings ( Duncan and Planes, 2015 ).

CASE 4. Supporting Fab Lab Facilitators to Develop Pedagogical Practices to Improve Learning in Digital Fabrication Activities

This case study was conducted also in the context of Fab Lab. The aim of this case study was to explore what technology experts should take into consideration in planning and facilitating students' learning processes in digital fabrication. This was done to provide research evidence about the design and implementation of digital fabrication activities. In practice, current undertakings in the local Fab Lab were explored from two perspectives: how current practices consider novice students' learning and how facilitators and teachers provide scaffolding in unstructured problem solving ( Pitkänen et al., 2019 ).

The local Fab Lab was established in 2015 (see https://www.oulu.fi/fablab/ ). Since then, Fab Lab has arranged different types of digital fabrication activities for school groups. The activities have typically included 2D and 3D design and manufacturing, prototyping with electronics, programming, and utilizing tools and machines to fabricate prototypes ( Georgiev et al., 2017 ; Iwata et al., 2019 ; Laru et al., 2019 ; Pitkänen et al., 2019 ).

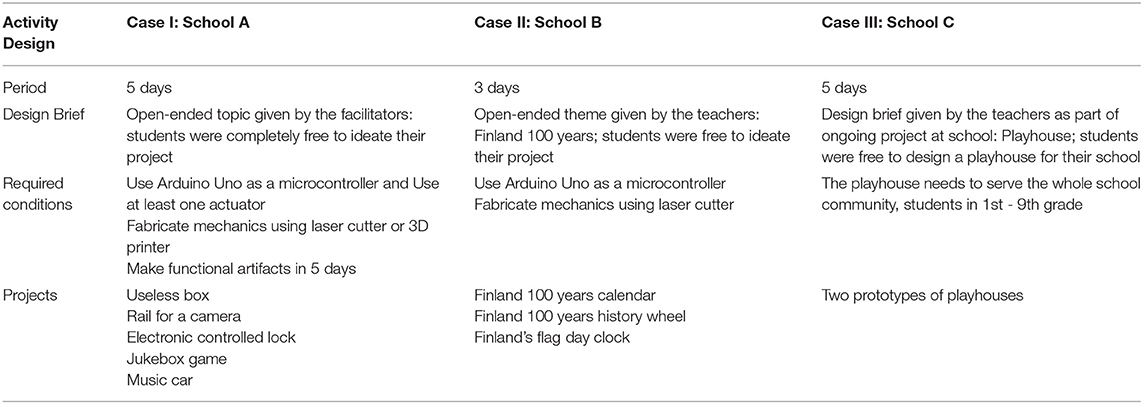

In this case study (Iwata et al., in review), three schools participated in digital fabrication activities in Fab Lab ( Table 2 ). The school participants, in total 41 students (aged 12–15 years old) and five teachers, were from three secondary schools. The activities were facilitated by two technology experts (facilitators), who work in the Fab Lab. In order to understand the making and digital fabrication activities, the participants were observed during the practice, and interviews of 14 students, the five teachers, and the two facilitators were conducted both during and at the end of the activities. Furthermore, the perspectives of the two expert groups (school teachers and Fab Lab facilitators) were investigated with focus group interviews.

Table 2 . The three schools participating in digital fabrication activities.

The students worked on projects in teams with different design briefs and required conditions provided by facilitators and/or the teachers. All student projects were complex and required knowledge and skills in multiple subjects, such as mathematics, physics, and art (STEAM concept) ( Table 2 ). Yet, these projects were difficult for them to complete without collaborative problem solving. The following excerpt is from a teacher's interview:

“One girl said that in normal group activities in school, she would have taken like the whole control, but this one was so huge, and she realized that she couldn't do that. So, she had to delegate. That was precious that she had to trust the team and that she can't control everything.”

Based on the interviews six factors were identified which influenced students' learning in the Fab Lab:

1) The tasks were complex and multidisciplinary.

2) Computers and digital tools were used frequently.

3) Students' own roles and responsibilities were emphasized in the guidance given.

4) Opportunities for reflection were supported.

5) Trial and error was encouraged.

6) An appropriate range of flexibility was embraced with time frame.

The following example shows how the school teacher explained the digital fabrication activities:

“You go and just try and error and it doesn't even matter if you totally succeed or fail on the product.… the important thing is what kind of cognitive skills and how you reflect, what you learn in the process, and if you came back, what would you do better.”

However, not all students who participated in these digital fabrication activities had previous knowledge and experience in the field. Moreover, many of them were not used to applied work methods that require competencies such as self-regulation, self-efficacy, and persistence. Based on the results, there is a need for defining clear learning goals and instructions, which would help students to engage in unstructured, open-ended, problem-solving activities. Furthermore, the lack of structure in the activities made both the teachers and facilitators point out the need to scaffold learning. The following is an excerpt from the interview of a teacher which underlines this need:

“….I feel like that we should guide them more…. giving them more guidance in choosing appropriate tasks they want to learn, because sometimes the tasks they choose might be too demanding for them to learn in a limited period time.”

Based on the analysis of the observations and interviews, several suggestions can be provided for integrating instructional scaffolding in the activities, taking into consideration novice learning, and the nature of unstructured problem solving activities. The first two elements relate to developing pedagogical practices in the activities: we recommend that teachers consider cognitive and affective processes of learning as a base for activity design and provide instructional scaffolding to improve opportunities for cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning. The next two elements suggest designing the activities in collaboration to enhance the application of digital fabrication to formal education, recommending that we familiarize teachers with Fab Labs and digital fabrication activities and increase collaboration between Fab Lab facilitators and school teachers.

Discussion—How to Design Cognitively Effortful and Affectively Meaningful Learning

Case studies of SNS, games for learning, makers education, and digital fabrication showed different ways of organizing digital education and illustrated in particular how different types of pedagogical design and digital tools have been used to support cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning in groups. In other words, in addition to knowledge co-construction, argumentation, and problem solving, opportunities for positive affective learning processes were provided, such as experiencing and expressing emotions in learning.

The first example, SNS, presented a learning environment that is familiar for students as an everyday communication tool. It provided an interaction arena to discuss and debate the course topics with the support of a micro-script ( Noroozi et al., 2012 ). In terms of the cognitive and affective potential of SNS, it can be concluded that structured roles functioned as a support for affective interactions by managing the discourse, inducing and resolving conflicts, and assisting in creating equal participation and feelings of belonging between students ( Isohätälä et al., 2017 ). However, as this case study was tightly pre-structured with a specific micro-script, the following examples presented open-ended collaborative problem-solving spaces. The second case study, the Minecraft game environment, showed how a commercial game was further designed and implemented in a primary school after school club. This was an example of a constructivist game approach where learners played but also modified their own games ( Kafai and Burke, 2015 ). This study showed how game experience prompted students' knowledge acquisition as well as supported students' learning skills in terms of programming and collaboration. Furthermore, the study also indicated that the experience was highly emotionally engaging for the students, based on the students' descriptions of their emotional experiences of playing the game and the experiences they had when the game was over.

Minecraft is a block based world of “digital making”; digital fabrication and making enables a more thorough design experience to plan and fabricate students' own artifacts in the situated (unstructured and open-ended) problem solving contexts ( Halverson and Sheridan, 2014 ; Martin, 2015 ; Taylor, 2016 ). Two different examples that were selected to illustrate maker education and digital fabrication showed the making activities in practice. The example from an early education context showed young children making in several contexts, including outdoor, and indoor locations ( Siklander et al., 2019 ). These activities were observed to contribute to affectivity by allowing children to experience several different types of emotions while learning, such as curiosity, joy, and excitement, but also negative feelings such as impatience, frustration, and disappointment ( Hyvönen and Kangas, 2007 ). These emotional expressions were particularly visible in their collaborative situations. The last case example turned the focus toward the teachers' and facilitators' point of view, investigating how they see making activities and how they understand what kind of support students need from them during these activities. This study, through the design principles of the Fab Lab activities, characterized the important factors that help teachers and facilitators to engage and support students' learning, such as implementing complex tasks, using digital tools, highlighting students' own roles and responsibilities, providing opportunities for reflection, encouraging trial and error, and providing flexibility in the timeframe ( Blikstein, 2013 ; Georgiev et al., 2017 ; Hira and Hynes, 2018 ; Iwata et al., 2019 ). In addition to these principles, this study pointed out that adequate scaffolding is needed to improve opportunities for cognitively effortful and affectively meaningful learning. This is especially important in the situations where maker activities and digital fabrication procedures are introduced to novice makers, since they need to be familiarized with making culture as well as possibilities and tools for making ( Gerjets and Hesse, 2004 ; Blikstein, 2013 ; Chu et al., 2017 ). Fab Lab and maker education differ in the use of social networking tools and games for learning, because digital tools are part of the making process and the learning environment is situated in the physical fabrication laboratory instead of online context ( Kim and Reeves, 2007 ; Qian and Clark, 2016 ).

In general, SNS, digital gaming, and maker education have become increasingly interesting as a learning context in a modern education, mixing technological and creative skills, exploration and discovery, problem-solving and playfulness, as well as formal and informal education ( Connolly et al., 2012 ; Davies and West, 2014 ; Georgiev et al., 2017 ). These types of learning opportunities have the potential to impact current and future educational practices and pedagogy. However, when critically evaluating these learning contexts' opportunities for cognitive and affective learning, it can be noted that the implementation of digital tools and environments alone is not enough ( Gerjets and Hesse, 2004 ). Therefore, planning and facilitating learning activities in digital education requires knowledge of both technology and pedagogy ( Laru et al., 2015 ; Häkkinen et al., 2017 ; Valtonen et al., 2019 ). For example, when designing learning with digital tools, it is important that technologies are embedded into the environment and that their use is designed prior the activities but also facilitated during the learning activities ( Kirschner et al., 2006 ; Dillenbourg, 2013 ). This is the case especially in the maker education context where tools and devices for various kinds of fabrication need to be provided for the use of students with heterogeneous skills, knowledge, and aims ( Blikstein, 2013 ; Chan and Blikstein, 2018 ).

In addition to pre-structured and facilitated learning activities, more spontaneous collaborative activities are recommended. This means that students should be provided opportunities to engage in learning activities which places students' needs, interests, and experiences as the starting point for their explorations. This type of learner-centered approach creates a learning environment that is built around creativity and allows personal emotional experiences, such as fun and enjoyment ( Hyvönen and Kangas, 2007 ; Hyvönen, 2011 ; Hyvönen et al., 2014 ). A sound learning environment also guides and supports students' interest and promotes their active involvement in learning ( Baker, 2015 ; Järvelä et al., 2016 ; Hadwin et al., 2018 ). In order to support learning activities in the ways described above, pedagogically sound practices will need to be established, and teachers' professional development will need to focus more on using technology to improve learning—not just on changing teachers' attitudes and abilities in more general ways ( Davies and West, 2014 ). To conclude, we agree with Lowyck ( 2014 , p. 15), who argues that “both learning theories and technology are empty concepts, when not connected to actors such as instructional designers, teachers and learners.” He continues with the image of teachers and learners as co-designers, which is well-aligned with the case studies presented in this paper, by claiming that “…they are co-designer of learning processes, which affect knowledge-construction, and management as well as products that result from collaboration in distributed knowledge environments.” Finally, this paper reinforces the idea suggested by Roschelle (2003) that we should focus on rich pedagogical practices and simple digital tools. In the context of the four case studies described in this paper, we can summarize that applying digital tools for education is meaningful when the aim is to provide opportunities for interactions and sharing ideas and thus increase students' opportunities to turn an active mind to multiple contexts.

This paper introduced studies that implemented the exploratory case approach and thus it can be criticized due to the lack of generalizability of the results. As case descriptions afford details and context specific illustrations, the possibility to draw general conclusions is limited ( Stake, 1995 ; Yin, 2013 ). In these case studies a various different types of methods were used. For example, discussion notes from Facebook group discussions were analyzed, interviews after the each face to face meeting during the Minecraft experiment were conducted, and photo elicitation interviews as a method in a Fab Lab working was used as well as observations and teacher and student interviews were done during a second Fab lab experiment. All these case studies and related data collections illustrate participants' experiences during the digital learning. As research of affective learning in digital education emerges, a key direction for future studies is to explore how tools and technologies support affective learning and interaction, but also how different types of pedagogical designs can scaffold affective learning ( Näykki et al., 2017a ). Design studies could explore and develop tools and design principles to support the use of social media tools in learning, the design and use of games for learning, and the involvement of makers and digital fabrication activities in educational settings. The current study provides interesting research questions based on our observations of the case studies to be explored in the future studies. For example, it can be explored how to design tools to support affective learning in gaming or making contexts where learning designs are not usually the main focus of the activity. The contexts of the cases were unstructured or open problem spaces, although special pedagogical designs were implemented. However, much remains to be understood regarding the types and configurations of technological and pedagogical support that best promote cognitive and affective processes of collaborative learning.

The results obtained from these case studies are applicable to formal education, such as early childhood education, primary school education, teacher education, and in-service training, but also to informal learning contexts, such as game designing and Fab Lab facilitation. Engagement in creative making activities, productive group work, and seamless use of technology are essential twenty-first-century skills needed in all fields of work and in life in general. Teachers at all educational levels have an especially crucial role in developing these skills in their students, and therefore future teachers have to be offered opportunities to experience and learn within various collaborative environments.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available Studies involving human subjects.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Additional Requirements

Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and the parents of non-adult participants for the purposes of research participation. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript can be made available by the authors, from request, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This study was supported by the Academy of Finland (316129) and Nordplus Horizontal (NPHZ-2018/10123).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Baker, M. J. (2015). Collaboration in collaborative learning. Interact. Stud. 16, 451–473. doi: 10.1075/is.16.3.05bak

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

M. J. Baker, J. Andriessen, and S. Järvelä (eds). (2013). Affective Learning Together: Social and Emotional Dimension of Collaborative Learning. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203069684

Barron, B. (2003). When smart groups fail. J. Learn. Sci. 12, 307–359. doi: 10.1207/S15327809JLS1203_1

Bayliss, J. D. (2012). “Teaching game AI through minecraft mods,” in Games Innovation Conference (IGIC) (Rochester, NY: IEEE International), 1–4. doi: 10.1109/IGIC.2012.6329841

Belland, B. R., Kim, C., and Hannafin, M. J. (2013). A framework for designing scaffolds that improve motivation and cognition. Educat. Psychol. 48, 243–270. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2013.838920

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bennett, G. (2010). Cast a wider net for reunion. Currents 36, 28–31.

Google Scholar