OPINION article

Factors affecting impulse buying behavior of consumers.

- Instituto Superior de Gestão, Lisbon, Portugal

In recent years, the study of consumer behavior has been marked by significant changes, mainly in decision-making process and consequently in the influences of purchase intention ( Stankevich, 2017 ).

The markets are different and characterized by an increased competition, as well a constant innovation in products and services available and a greater number of companies in the same market. In this scenario it is essential to know the consumer well ( Varadarajan, 2020 ). It is through the analysis of the factors that have a direct impact on consumer behavior that it is possible to innovate and meet their expectations. This research is essential for marketers to be able to improve their campaigns and reach the target audience more effectively ( Ding et al., 2020 ).

Consumer behavior refers to the activities directly involved in obtaining products /services, so it includes the decision-making processes that precede and succeed these actions. Thus, it appears that the advertising message can cause a certain psychological influence that motivates individuals to desire and, consequently, buy a certain product/service ( Wertenbroch et al., 2020 ).

Studies developed by Meena (2018) show that from a young age one begins to have a preference for one product/service over another, as we are confronted with various commercial stimuli that shape our choices. The sales promotion has become one of the most powerful tools to change the perception of buyers and has a significant impact on their purchase decision ( Khan et al., 2019 ). Advertising has a great capacity to influence and persuade, and even the most innocuous, can cause changes in behavior that affect the consumer's purchase intention. Falebita et al. (2020) consider this influence predominantly positive, as shown by about 84.0% of the total number of articles reviewed in the study developed by these authors.

Kumar et al. (2020) add that psychological factors have a strong implication in the purchase decision, as we easily find people who, after having purchased a product/ service, wonder about the reason why they did it. It is essential to understand the mental triggers behind the purchase decision process, which is why consumer psychology is related to marketing strategies ( Ding et al., 2020 ). It is not uncommon for the two areas to use the same models to explain consumer behavior and the reasons that trigger impulse purchases. Consumers are attracted by advertising and the messages it conveys, which is reflected in their behavior and purchase intentions ( Varadarajan, 2020 ).

Impulse buying has been studied from several perspectives, namely: (i) rational processes; (ii) emotional resources; (iii) the cognitive currents arising from the theory of social judgment; (iv) persuasive communication; (v) and the effects of advertising on consumer behavior ( Malter et al., 2020 ).

The causes of impulsive behavior are triggered by an irresistible force to buy and an inability to evaluate its consequences. Despite being aware of the negative effects of buying, there is an enormous desire to immediately satisfy your most pressing needs ( Meena, 2018 ).

The importance of impulse buying in consumer behavior has been studied since the 1940's, since it represents between 40.0 and 80.0% of all purchases. This type of purchase obeys non-rational reasons that are characterized by the sudden appearance and the (in) satisfaction between the act of buying and the results obtained ( Reisch and Zhao, 2017 ). Aragoncillo and Orús (2018) also refer that a considerable percentage of sales comes from purchases that are not planned and do not correspond to the intended products before entering the store.

According to Burton et al. (2018) , impulse purchases occur when there is a sudden and strong emotional desire, which arises from a reactive behavior that is characterized by low cognitive control. This tendency to buy spontaneously and without reflection can be explained by the immediate gratification it provides to the buyer ( Pradhan et al., 2018 ).

Impulsive shopping in addition to having an emotional content can be triggered by several factors, including: the store environment, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and the emotional state of the consumer at that time ( Gogoi and Shillong, 2020 ). We believe that impulse purchases can be stimulated by an unexpected need, by a visual stimulus, a promotional campaign and/or by the decrease of the cognitive capacity to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of that purchase.

The buying experience increasingly depends on the interaction between the person and the point of sale environment, but it is not just the atmosphere that stimulates the impulsive behavior of the consumer. The sensory and psychological factors associated with the type of products, the knowledge about them and brand loyalty, often end up overlapping the importance attributed to the physical environment ( Platania et al., 2016 ).

The impulse buying causes an emotional lack of control generated by the conflict between the immediate reward and the negative consequences that the purchase can originate, which can trigger compulsive behaviors that can become chronic and pathological ( Pandya and Pandya, 2020 ).

Sohn and Ko (2021) , argue that although all impulse purchases can be considered as unplanned, not all unplanned purchases can be considered impulsive. Unplanned purchases can occur, simply because the consumer needs to purchase a product, but for whatever reason has not been placed on the shopping list in advance. This suggests that unplanned purchases are not necessarily accompanied by the urgent desire that generally characterizes impulse purchases.

The impulse purchases arise from sensory experiences (e.g., store atmosphere, product layout), so purchases made in physical stores tend to be more impulsive than purchases made online. This type of shopping results from the stimulation of the five senses and the internet does not have this capacity, so that online shopping can be less encouraging of impulse purchases than shopping in physical stores ( Moreira et al., 2017 ).

Researches developed by Aragoncillo and Orús (2018) reveal that 40.0% of consumers spend more money than planned, in physical stores compared to 25.0% in online purchases. This situation can be explained by the fact that consumers must wait for the product to be delivered when they buy online and this time interval may make impulse purchases unfeasible.

Following the logic of Platania et al. (2017) we consider that impulse buying takes socially accepted behavior to the extreme, which makes it difficult to distinguish between normal consumption and pathological consumption. As such, we believe that compulsive buying behavior does not depend only on a single variable, but rather on a combination of sociodemographic, emotional, sensory, genetic, psychological, social, and cultural factors. Personality traits also have an important role in impulse buying. Impulsive buyers have low levels of self-esteem, high levels of anxiety, depression and negative mood and a strong tendency to develop obsessive-compulsive disorders. However, it appears that the degree of uncertainty derived from the pandemic that hit the world and the consequent economic crisis, seems to have changed people's behavior toward a more planned and informed consumption ( Sheth, 2020 ).

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Aragoncillo, L., and Orús, C. (2018). Impulse buying behaviour: na online-offline comparative and the impact of social media. Spanish J. Market. 22, 42–62. doi: 10.1108/SJME-03-2018-007

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Burton, J., Gollins, J., McNeely, L., and Walls, D. (2018). Revisting the relationship between Ad frequency and purchase intentions. J. Advertising Res. 59, 27–39. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2018-031

Ding, Y., DeSarbo, W., Hanssens, D., Jedidi, K., Lynch, J., and Lehmann, D. (2020). The past, present, and future of measurements and methods in marketing analysis. Market. Lett. 31, 175–186. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09527-7

Falebita, O., Ogunlusi, C., and Adetunji, A. (2020). A review of advertising management and its impact on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Agri. Innov. Technol. Global. 1, 354–374. doi: 10.1504/IJAITG.2020.111885

Gogoi, B., and Shillong, I. (2020). Do impulsive buying influence compulsive buying? Acad. Market. Stud. J. 24, 1–15.

Google Scholar

Khan, M., Tanveer, A., and Zubair, S. (2019). Impact of sales promotion on consumer buying behavior: a case of modern trade, Pakistan. Govern. Manag. Rev. 4, 38–53. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3441058

Kumar, A., Chaudhuri, S., Bhardwaj, A., and Mishra, P. (2020). Impulse buying and post-purchase regret: a study of shopping behavior for the purchase of grocery products. Int. J. Manag. 11, 614–624. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3786039

Malter, M., Holbrook, M., Kahn, B., Parker, J., and Lehmann, D. (2020). The past, present, and future of consumer research. Market. Lett. 31, 137–149. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meena, S. (2018). Consumer psychology and marketing. Int. J. Res. Analyt. Rev. 5, 218–222.

Moreira, A., Fortes, N., and Santiago, R. (2017). Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 18, 68–83. doi: 10.3846/16111699.2016.1252793

Pandya, P., and Pandya, K. (2020). An empirical study of compulsive buying behaviour of consumers. Alochana Chakra J. 9, 4102–4114.

Platania, M., Platania, S., and Santisi, G. (2016). Entertainment marketing, experiential consumption and consumer behavior: the determinant of choice of wine in the store. Wine Econ. Policy 5, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.wep.2016.10.001

Platania, S., Castellano, S., Santisi, G., and Di Nuovo, S. (2017). Correlati di personalità della tendenza allo shopping compulsivo. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 64, 137–158.

Pradhan, D., Israel, D., and Jena, A. (2018). Materialism and compulsive buying behaviour: the role of consumer credit card use and impulse buying. Asia Pacific J. Market. Logist. 30,1355–5855. doi: 10.1108/APJML-08-2017-0164

Reisch, L., and Zhao, M. (2017). Behavioural economics, consumer behaviour and consumer policy: state of the art. Behav. Public Policy 1, 190–206. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2017.1

Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 117, 280–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059

Sohn, Y., and Ko, M. (2021). The impact of planned vs. unplanned purchases on subsequent purchase decision making in sequential buying situations. J. Retail. Consumer Servic. 59, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102419

Stankevich, A. (2017). Explaining the consumer decision-making process: critical literature review. J. Int. Bus. Res. Market. 2, 7–14. doi: 10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.26.3001

Varadarajan, R. (2020). Customer information resources advantage, marketing strategy and business performance: a market resources based view. Indus. Market. Manag. 89, 89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.03.003

Wertenbroch, K., Schrift, R., Alba, J., Barasch, A., Bhattacharjee, A., Giesler, M., et al. (2020). Autonomy in consumer choice. Market. Lett. 31, 429–439. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09521-z

Keywords: consumer behavior, purchase intention, impulse purchase, emotional influences, marketing strategies

Citation: Rodrigues RI, Lopes P and Varela M (2021) Factors Affecting Impulse Buying Behavior of Consumers. Front. Psychol. 12:697080. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697080

Received: 19 April 2021; Accepted: 10 May 2021; Published: 02 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Rodrigues, Lopes and Varela. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosa Isabel Rodrigues, rosa.rodrigues@isg.pt

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The past, present, and future of consumer research

- Published: 13 June 2020

- Volume 31 , pages 137–149, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Maayan S. Malter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0383-7925 1 ,

- Morris B. Holbrook 1 ,

- Barbara E. Kahn 2 ,

- Jeffrey R. Parker 3 &

- Donald R. Lehmann 1

45k Accesses

37 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

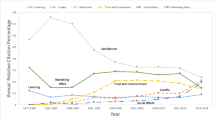

In this article, we document the evolution of research trends (concepts, methods, and aims) within the field of consumer behavior, from the time of its early development to the present day, as a multidisciplinary area of research within marketing. We describe current changes in retailing and real-world consumption and offer suggestions on how to use observations of consumption phenomena to generate new and interesting consumer behavior research questions. Consumption continues to change with technological advancements and shifts in consumers’ values and goals. We cannot know the exact shape of things to come, but we polled a sample of leading scholars and summarize their predictions on where the field may be headed in the next twenty years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Consumer Behavior Research Methods

Consumer dynamics: theories, methods, and emerging directions

Understanding effect sizes in consumer psychology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Beginning in the late 1950s, business schools shifted from descriptive and practitioner-focused studies to more theoretically driven and academically rigorous research (Dahl et al. 1959 ). As the field expanded from an applied form of economics to embrace theories and methodologies from psychology, sociology, anthropology, and statistics, there was an increased emphasis on understanding the thoughts, desires, and experiences of individual consumers. For academic marketing, this meant that research not only focused on the decisions and strategies of marketing managers but also on the decisions and thought processes on the other side of the market—customers.

Since then, the academic study of consumer behavior has evolved and incorporated concepts and methods, not only from marketing at large but also from related social science disciplines, and from the ever-changing landscape of real-world consumption behavior. Its position as an area of study within a larger discipline that comprises researchers from diverse theoretical backgrounds and methodological training has stirred debates over its identity. One article describes consumer behavior as a multidisciplinary subdiscipline of marketing “characterized by the study of people operating in a consumer role involving acquisition, consumption, and disposition of marketplace products, services, and experiences” (MacInnis and Folkes 2009 , p. 900).

This article reviews the evolution of the field of consumer behavior over the past half century, describes its current status, and predicts how it may evolve over the next twenty years. Our review is by no means a comprehensive history of the field (see Schumann et al. 2008 ; Rapp and Hill 2015 ; Wang et al. 2015 ; Wilkie and Moore 2003 , to name a few) but rather focuses on a few key thematic developments. Though we observe many major shifts during this period, certain questions and debates have persisted: Does consumer behavior research need to be relevant to marketing managers or is there intrinsic value from studying the consumer as a project pursued for its own sake? What counts as consumption: only consumption from traditional marketplace transactions or also consumption in a broader sense of non-marketplace interactions? Which are the most appropriate theoretical traditions and methodological tools for addressing questions in consumer behavior research?

2 A brief history of consumer research over the past sixty years—1960 to 2020

In 1969, the Association for Consumer Research was founded and a yearly conference to share marketing research specifically from the consumer’s perspective was instituted. This event marked the culmination of the growing interest in the topic by formalizing it as an area of research within marketing (consumer psychology had become a formalized branch of psychology within the APA in 1960). So, what was consumer behavior before 1969? Scanning current consumer-behavior doctoral seminar syllabi reveals few works predating 1969, with most of those coming from psychology and economics, namely Herbert Simon’s A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice (1955), Abraham Maslow’s A Theory of Human Motivation (1943), and Ernest Dichter’s Handbook of Consumer Motivations (1964). In short, research that illuminated and informed our understanding of consumer behavior prior to 1969 rarely focused on marketing-specific topics, much less consumers or consumption (Dichter’s handbook being a notable exception). Yet, these works were crucial to the rise of consumer behavior research because, in the decades after 1969, there was a shift within academic marketing to thinking about research from a behavioral or decision science perspective (Wilkie and Moore 2003 ). The following section details some ways in which this shift occurred. We draw on a framework proposed by the philosopher Larry Laudan ( 1986 ), who distinguished among three inter-related aspects of scientific inquiry—namely, concepts (the relevant ideas, theories, hypotheses, and constructs); methods (the techniques employed to test and validate these concepts); and aims (the purposes or goals that motivate the investigation).

2.1 Key concepts in the late - 1960s

During the late-1960s, we tended to view the buyer as a computer-like machine for processing information according to various formal rules that embody economic rationality to form a preference for one or another option in order to arrive at a purchase decision. This view tended to manifest itself in a couple of conspicuous ways. The first was a model of buyer behavior introduced by John Howard in 1963 in the second edition of his marketing textbook and quickly adopted by virtually every theorist working in our field—including, Howard and Sheth (of course), Engel-Kollat-&-Blackwell, Franco Nicosia, Alan Andreasen, Jim Bettman, and Joel Cohen. Howard’s great innovation—which he based on a scheme that he had found in the work of Plato (namely, the linkages among Cognition, Affect, and Conation)—took the form of a boxes-and-arrows formulation heavily influenced by the approach to organizational behavior theory that Howard (University of Pittsburgh) had picked up from Herbert Simon (Carnegie Melon University). The model represented a chain of events

where I = inputs of information (from advertising, word-of-mouth, brand features, etc.); C = cognitions (beliefs or perceptions about a brand); A = Affect (liking or preference for the brand); B = behavior (purchase of the brand); and S = satisfaction (post-purchase evaluation of the brand that feeds back onto earlier stages of the sequence, according to a learning model in which reinforced behavior tends to be repeated). This formulation lay at the heart of Howard’s work, which he updated, elaborated on, and streamlined over the remainder of his career. Importantly, it informed virtually every buyer-behavior model that blossomed forth during the last half of the twentieth century.

To represent the link between cognitions and affect, buyer-behavior researchers used various forms of the multi-attribute attitude model (MAAM), originally proposed by psychologists such as Fishbein and Rosenberg as part of what Fishbein and Ajzen ( 1975 ) called the theory of reasoned action. Under MAAM, cognitions (beliefs about brand attributes) are weighted by their importance and summed to create an explanation or prediction of affect (liking for a brand or preference for one brand versus another), which in turn determines behavior (choice of a brand or intention to purchase a brand). This took the work of economist Kelvin Lancaster (with whom Howard interacted), which assumed attitude was based on objective attributes, and extended it to include subjective ones (Lancaster 1966 ; Ratchford 1975 ). Overall, the set of concepts that prevailed in the late-1960s assumed the buyer exhibited economic rationality and acted as a computer-like information-processing machine when making purchase decisions.

2.2 Favored methods in the late-1960s

The methods favored during the late-1960s tended to be almost exclusively neo-positivistic in nature. That is, buyer-behavior research adopted the kinds of methodological rigor that we associate with the physical sciences and the hypothetico-deductive approaches advocated by the neo-positivistic philosophers of science.

Thus, the accepted approaches tended to be either experimental or survey based. For example, numerous laboratory studies tested variations of the MAAM and focused on questions about how to measure beliefs, how to weight the beliefs, how to combine the weighted beliefs, and so forth (e.g., Beckwith and Lehmann 1973 ). Here again, these assumed a rational economic decision-maker who processed information something like a computer.

Seeking rigor, buyer-behavior studies tended to be quantitative in their analyses, employing multivariate statistics, structural equation models, multidimensional scaling, conjoint analysis, and other mathematically sophisticated techniques. For example, various attempts to test the ICABS formulation developed simultaneous (now called structural) equation models such as those deployed by Farley and Ring ( 1970 , 1974 ) to test the Howard and Sheth ( 1969 ) model and by Beckwith and Lehmann ( 1973 ) to measure halo effects.

2.3 Aims in the late-1960s

During this time period, buyer-behavior research was still considered a subdivision of marketing research, the purpose of which was to provide insights useful to marketing managers in making strategic decisions. Essentially, every paper concluded with a section on “Implications for Marketing Managers.” Authors who failed to conform to this expectation could generally count on having their work rejected by leading journals such as the Journal of Marketing Research ( JMR ) and the Journal of Marketing ( JM ).

2.4 Summary—the three R’s in the late-1960s

Starting in the late-1960s to the early-1980s, virtually every buyer-behavior researcher followed the traditional approach to concepts, methods, and aims, now encapsulated under what we might call the three R’s —namely, rationality , rigor , and relevance . However, as we transitioned into the 1980s and beyond, that changed as some (though by no means all) consumer researchers began to expand their approaches and to evolve different perspectives.

2.5 Concepts after 1980

In some circles, the traditional emphasis on the buyer’s rationality—that is, a view of the buyer as a rational-economic, decision-oriented, information-processing, computer-like machine for making choices—began to evolve in at least two primary ways.

First, behavioral economics (originally studied in marketing under the label Behavioral Decision Theory)—developed in psychology by Kahneman and Tversky, in economics by Thaler, and applied in marketing by a number of forward-thinking theorists (e.g., Eric Johnson, Jim Bettman, John Payne, Itamar Simonson, Jay Russo, Joel Huber, and more recently, Dan Ariely)—challenged the rationality of consumers as decision-makers. It was shown that numerous commonly used decision heuristics depart from rational choice and are exceptions to the traditional assumptions of economic rationality. This trend shed light on understanding consumer financial decision-making (Prelec and Loewenstein 1998 ; Gourville 1998 ; Lynch Jr 2011 ) and how to develop “nudges” to help consumers make better decisions for their personal finances (summarized in Johnson et al. 2012 ).

Second, the emerging experiential view (anticipated by Alderson, Levy, and others; developed by Holbrook and Hirschman, and embellished by Schmitt, Pine, and Gilmore, and countless followers) regarded consumers as flesh-and-blood human beings (rather than as information-processing computer-like machines), focused on hedonic aspects of consumption, and expanded the concepts embodied by ICABS (Table 1 ).

2.6 Methods after 1980

The two burgeoning areas of research—behavioral economics and experiential theories—differed in their methodological approaches. The former relied on controlled randomized experiments with a focus on decision strategies and behavioral outcomes. For example, experiments tested the process by which consumers evaluate options using information display boards and “Mouselab” matrices of aspects and attributes (Payne et al. 1988 ). This school of thought also focused on behavioral dependent measures, such as choice (Huber et al. 1982 ; Simonson 1989 ; Iyengar and Lepper 2000 ).

The latter was influenced by post-positivistic philosophers of science—such as Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend, and Richard Rorty—and approaches expanded to include various qualitative techniques (interpretive, ethnographic, humanistic, and even introspective methods) not previously prominent in the field of consumer research. These included:

Interpretive approaches —such as those drawing on semiotics and hermeneutics—in an effort to gain a richer understanding of the symbolic meanings involved in consumption experiences;

Ethnographic approaches — borrowed from cultural anthropology—such as those illustrated by the influential Consumer Behavior Odyssey (Belk et al. 1989 ) and its discoveries about phenomena related to sacred aspects of consumption or the deep meanings of collections and other possessions;

Humanistic approaches —such as those borrowed from cultural studies or from literary criticism and more recently gathered together under the general heading of consumer culture theory ( CCT );

Introspective or autoethnographic approaches —such as those associated with a method called subjective personal introspection ( SPI ) that various consumer researchers like Sidney Levy and Steve Gould have pursued to gain insights based on their own private lives.

These qualitative approaches tended not to appear in the more traditional journals such as the Journal of Marketing , Journal of Marketing Research , or Marketing Science . However, newer journals such as Consumption, Markets, & Culture and Marketing Theory began to publish papers that drew on the various interpretive, ethnographic, humanistic, or introspective methods.

2.7 Aims after 1980

In 1974, consumer research finally got its own journal with the launch of the Journal of Consumer Research ( JCR ). The early editors of JCR —especially Bob Ferber, Hal Kassarjian, and Jim Bettman—held a rather divergent attitude about the importance or even the desirability of managerial relevance as a key goal of consumer studies. Under their influence, some researchers began to believe that consumer behavior is a phenomenon worthy of study in its own right—purely for the purpose of understanding it better. The journal incorporated articles from an array of methodologies: quantitative (both secondary data analysis and experimental techniques) and qualitative. The “right” balance between theoretical insight and substantive relevance—which are not in inherent conflict—is a matter of debate to this day and will likely continue to be debated well into the future.

2.8 Summary—the three I’s after 1980

In sum, beginning in the early-1980s, consumer research branched out. Much of the work in consumer studies remained within the earlier tradition of the three R’s—that is, rationality (an information-processing decision-oriented buyer), rigor (neo-positivistic experimental designs and quantitative techniques), and relevance (usefulness to marketing managers). Nonetheless, many studies embraced enlarged views of the three major aspects that might be called the three I’s —that is, irrationality (broadened perspectives that incorporate illogical, heuristic, experiential, or hedonic aspects of consumption), interpretation (various qualitative or “postmodern” approaches), and intrinsic motivation (the joy of pursuing a managerially irrelevant consumer study purely for the sake of satisfying one’s own curiosity, without concern for whether it does or does not help a marketing practitioner make a bigger profit).

3 The present—the consumer behavior field today

3.1 present concepts.

In recent years, technological changes have significantly influenced the nature of consumption as the customer journey has transitioned to include more interaction on digital platforms that complements interaction in physical stores. This shift poses a major conceptual challenge in understanding if and how these technological changes affect consumption. Does the medium through which consumption occurs fundamentally alter the psychological and social processes identified in earlier research? In addition, this shift allows us to collect more data at different stages of the customer journey, which further allows us to analyze behavior in ways that were not previously available.

Revisiting the ICABS framework, many of the previous concepts are still present, but we are now addressing them through a lens of technological change (Table 2 )

. In recent years, a number of concepts (e.g., identity, beliefs/lay theories, affect as information, self-control, time, psychological ownership, search for meaning and happiness, social belonging, creativity, and status) have emerged as integral factors that influence and are influenced by consumption. To better understand these concepts, a number of influential theories from social psychology have been adopted into consumer behavior research. Self-construal (Markus and Kitayama 1991 ), regulatory focus (Higgins 1998 ), construal level (Trope and Liberman 2010 ), and goal systems (Kruglanski et al. 2002 ) all provide social-cognition frameworks through which consumer behavior researchers study the psychological processes behind consumer behavior. This “adoption” of social psychological theories into consumer behavior is a symbiotic relationship that further enhances the theories. Tory Higgins happily stated that he learned more about his own theories from the work of marketing academics (he cited Angela Lee and Michel Pham) in further testing and extending them.

3.2 Present Methods

Not only have technological advancements changed the nature of consumption but they have also significantly influenced the methods used in consumer research by adding both new sources of data and improved analytical tools (Ding et al. 2020 ). Researchers continue to use traditional methods from psychology in empirical research (scale development, laboratory experiments, quantitative analyses, etc.) and interpretive approaches in qualitative research. Additionally, online experiments using participants from panels such as Amazon Mechanical Turk and Prolific have become commonplace in the last decade. While they raise concerns about the quality of the data and about the external validity of the results, these online experiments have greatly increased the speed and decreased the cost of collecting data, so researchers continue to use them, albeit with some caution. Reminiscent of the discussion in the 1970s and 1980s about the use of student subjects, the projectability of the online responses and of an increasingly conditioned “professional” group of online respondents (MTurkers) is a major concern.

Technology has also changed research methodology. Currently, there is a large increase in the use of secondary data thanks to the availability of Big Data about online and offline behavior. Methods in computer science have advanced our ability to analyze large corpuses of unstructured data (text, voice, visual images) in an efficient and rigorous way and, thus, to tap into a wealth of nuanced thoughts, feelings, and behaviors heretofore only accessible to qualitative researchers through laboriously conducted content analyses. There are also new neuro-marketing techniques like eye-tracking, fMRI’s, body arousal measures (e.g., heart rate, sweat), and emotion detectors that allow us to measure automatic responses. Lastly, there has been an increase in large-scale field experiments that can be run in online B2C marketplaces.

3.3 Present Aims

Along with a focus on real-world observations and data, there is a renewed emphasis on managerial relevance. Countless conference addresses and editorials in JCR , JCP , and other journals have emphasized the importance of making consumer research useful outside of academia—that is, to help companies, policy makers, and consumers. For instance, understanding how the “new” consumer interacts over time with other consumers and companies in the current marketplace is a key area for future research. As global and social concerns become more salient in all aspects of life, issues of long-term sustainability, social equality, and ethical business practices have also become more central research topics. Fortunately, despite this emphasis on relevance, theoretical contributions and novel ideas are still highly valued. An appropriate balance of theory and practice has become the holy grail of consumer research.

The effects of the current trends in real-world consumption will increase in magnitude with time as more consumers are digitally native. Therefore, a better understanding of current consumer behavior can give us insights and help predict how it will continue to evolve in the years to come.

4 The future—the consumer behavior field in 2040

The other papers use 2030 as a target year but we asked our survey respondents to make predictions for 2040 and thus we have a different future target year.

Niels Bohr once said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” Indeed, it would be a fool’s errand for a single person to hazard a guess about the state of the consumer behavior field twenty years from now. Therefore, predictions from 34 active consumer researchers were collected to address this task. Here, we briefly summarize those predictions.

4.1 Future Concepts

While few respondents proffered guesses regarding specific concepts that would be of interest twenty years from now, many suggested broad topics and trends they expected to see in the field. Expectations for topics could largely be grouped into three main areas. Many suspected that we will be examining essentially the same core topics, perhaps at a finer-grained level, from different perspectives or in ways that we currently cannot utilize due to methodological limitations (more on methods below). A second contingent predicted that much research would center on the impending crises the world faces today, most mentioning environmental and social issues (the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet begun when these predictions were collected and, unsurprisingly, was not anticipated by any of our respondents). The last group, citing the widely expected profound impact of AI on consumers’ lives, argued that AI and other technology-related topics will be dominant subjects in consumer research circa 2040.

While the topic of technology is likely to be focal in the field, our current expectations for the impact of technology on consumers’ lives are narrower than it should be. Rather than merely offering innumerable conveniences and experiences, it seems likely that technology will begin to be integrated into consumers’ thoughts, identities, and personal relationships—probably sooner than we collectively expect. The integration of machines into humans’ bodies and lives will present the field with an expanding list of research questions that do not exist today. For example, how will the concepts of the self, identity, privacy, and goal pursuit change when web-connected technology seamlessly integrates with human consciousness and cognition? Major questions will also need to be answered regarding philosophy of mind, ethics, and social inequality. We suspect that the impact of technology on consumers and consumer research will be far broader than most consumer-behavior researchers anticipate.

As for broader trends within consumer research, there were two camps: (1) those who expect (or hope) that dominant theories (both current and yet to be developed) will become more integrated and comprehensive and (2) those who expect theoretical contributions to become smaller and smaller, to the point of becoming trivial. Both groups felt that current researchers are filling smaller cracks than before, but disagreed on how this would ultimately be resolved.

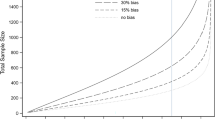

4.2 Future Methods

As was the case with concepts, respondents’ expectations regarding consumer-research methodologies in 2030 can also be divided into three broad baskets. Unsurprisingly, many indicated that we would be using many technologies not currently available or in wide use. Perhaps more surprising was that most cited the use of technology such as AI, machine-learning algorithms, and robots in designing—as opposed to executing or analyzing—experiments. (Some did point to the use of technologies such as virtual reality in the actual execution of experiments.) The second camp indicated that a focus on reliable and replicable results (discussed further below) will encourage a greater tendency for pre-registering studies, more use of “Big Data,” and a demand for more studies per paper (versus more papers per topic, which some believe is a more fruitful direction). Finally, the third lot indicated that “real data” would be in high demand, thereby necessitating the use of incentive-compatible, consequential dependent variables and a greater prevalence of field studies in consumer research.

As a result, young scholars would benefit from developing a “toolkit” of methodologies for collecting and analyzing the abundant new data of interest to the field. This includes (but is not limited to) a deep understanding of designing and implementing field studies (Gerber and Green 2012 ), data analysis software (R, Python, etc.), text mining and analysis (Humphreys and Wang 2018 ), and analytical tools for other unstructured forms of data such as image and sound. The replication crisis in experimental research means that future scholars will also need to take a more critical approach to validity (internal, external, construct), statistical power, and significance in their work.

4.3 Future Aims

While there was an air of existential concern about the future of the field, most agreed that the trend will be toward increasing the relevance and reliability of consumer research. Specifically, echoing calls from journals and thought leaders, the respondents felt that papers will need to offer more actionable implications for consumers, managers, or policy makers. However, few thought that this increased focus would come at the expense of theoretical insights, suggesting a more demanding overall standard for consumer research in 2040. Likewise, most felt that methodological transparency, open access to data and materials, and study pre-registration will become the norm as the field seeks to allay concerns about the reliability and meaningfulness of its research findings.

4.4 Summary - Future research questions and directions

Despite some well-justified pessimism, the future of consumer research is as bright as ever. As we revised this paper amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that many aspects of marketplace behavior, consumption, and life in general will change as a result of this unprecedented global crisis. Given this, and the radical technological, social, and environmental changes that loom on the horizon, consumer researchers will have a treasure trove of topics to tackle in the next ten years, many of which will carry profound substantive importance. While research approaches will evolve, the core goals will remain consistent—namely, to generate theoretically insightful, empirically supported, and substantively impactful research (Table 3 ).

5 Conclusion

At any given moment in time, the focal concepts, methods, and aims of consumer-behavior scholarship reflect both the prior development of the field and trends in the larger scientific community. However, despite shifting trends, the core of the field has remained constant—namely, to understand the motivations, thought processes, and experiences of individuals as they consume goods, services, information, and other offerings, and to use these insights to develop interventions to improve both marketing strategy for firms and consumer welfare for individuals and groups. Amidst the excitement of new technologies, social trends, and consumption experiences, it is important to look back and remind ourselves of the insights the field has already generated. Effectively integrating these past findings with new observations and fresh research will help the field advance our understanding of consumer behavior.

Beckwith, N. E., & Lehmann, D. R. (1973). The importance of differential weights in multiple attribute models of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 10 (2), 141–145.

Article Google Scholar

Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry Jr., J. F. (1989). The sacred and the profane in consumer behavior: theodicy on the odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (1), 1–38.

Dahl, R. A., Haire, M., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1959). Social science research on business: product and potential . New York: Columbia University Press.

Ding, Y., DeSarbo, W. S., Hanssens, D. M., Jedidi, K., Lynch Jr., J. G., & Lehmann, D. R. (2020). The past, present, and future of measurements and methods in marketing analysis. Marketing Letters, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09527-7 .

Farley, J. U., & Ring, L. W. (1970). An empirical test of the Howard-Sheth model of buyer behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 7 (4), 427–438.

Farley, J. U., & Ring, L. W. (1974). “Empirical” specification of a buyer behavior model. Journal of Marketing Research, 11 (1), 89–96.

Google Scholar

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research . Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2012). Field experiments: design, analysis, and interpretation . New York: WW Norton.

Gourville, J. T. (1998). Pennies-a-day: the effect of temporal reframing on transaction evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (4), 395–408.

Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30 , 1–46.

Howard, J. A., & Sheth, J. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior . New York: Wiley.

Huber, J., Payne, J. W., & Puto, C. (1982). Adding asymmetrically dominated alternatives: violations of regularity and the similarity hypothesis. Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (1), 90–98.

Humphreys, A., & Wang, R. J. H. (2018). Automated text analysis for consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (6), 1274–1306.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79 (6), 995–1006.

Johnson, E. J., Shu, S. B., Dellaert, B. G., Fox, C., Goldstein, D. G., Häubl, G., et al. (2012). Beyond nudges: tools of a choice architecture. Marketing Letters, 23 (2), 487–504.

Kruglanski, A. W., Shah, J. Y., Fishbach, A., Friedman, R., Chun, W. Y., & Sleeth-Keppler, D. (2002). A theory of goal systems. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34 , 311–378.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new theory of consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 74 , 132–157.

Laudan, L. (1986). Methodology’s prospects. In PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, 1986 (2), 347–354.

Lynch Jr., J. G. (2011). Introduction to the journal of marketing research special interdisciplinary issue on consumer financial decision making. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (SPL) Siv–Sviii.

MacInnis, D. J., & Folkes, V. S. (2009). The disciplinary status of consumer behavior: a sociology of science perspective on key controversies. Journal of Consumer Research, 36 (6), 899–914.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2), 224–253.

Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1988). Adaptive strategy selection in decision making. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14 (3), 534–552.

Prelec, D., & Loewenstein, G. (1998). The red and the black: mental accounting of savings and debt. Marketing Science, 17 (1), 4–28.

Rapp, J. M., & Hill, R. P. (2015). Lordy, Lordy, look who’s 40! The Journal of Consumer Research reaches a milestone. Journal of Consumer Research, 42 (1), 19–29.

Ratchford, B. T. (1975). The new economic theory of consumer behavior: an interpretive essay. Journal of Consumer Research, 2 (2), 65–75.

Schumann, D. W., Haugtvedt, C. P., & Davidson, E. (2008). History of consumer psychology. In Haugtvedt, C. P., Herr, P. M., & Kardes, F. R. eds. Handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 3-28). New York: Erlbaum.

Simonson, I. (1989). Choice based on reasons: the case of attraction and compromise effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (2), 158–174.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117 (2), 440–463.

Wang, X., Bendle, N. T., Mai, F., & Cotte, J. (2015). The journal of consumer research at 40: a historical analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 42 (1), 5–18.

Wilkie, W. L., & Moore, E. S. (2003). Scholarly research in marketing: exploring the “4 eras” of thought development. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 22 (2), 116–146.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Columbia Business School, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Maayan S. Malter, Morris B. Holbrook & Donald R. Lehmann

The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Barbara E. Kahn

Department of Marketing, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Jeffrey R. Parker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maayan S. Malter .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Malter, M.S., Holbrook, M.B., Kahn, B.E. et al. The past, present, and future of consumer research. Mark Lett 31 , 137–149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

Download citation

Published : 13 June 2020

Issue Date : September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Consumer behavior

- Information processing

- Judgement and decision-making

- Consumer culture theory

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Impulse buying behaviour: an online-offline comparative and the impact of social media

Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC

ISSN : 2444-9695

Article publication date: 24 April 2018

Issue publication date: 5 June 2018

This paper aims to explore the phenomenon of impulse buying in the fashion industry. The online and offline channels are compared to determine which is perceived as leading to more impulsive buying.

Design/methodology/approach

As the result of the literature review, three research questions are proposed and examined through an online self-administered survey with 212 valid responses.

Results show that the offline channel is slightly more encouraging of impulse buying than the online channel; factors that encourage online impulse buying explain this behaviour to a greater extent than do discouraging factors; social networks can have a big impact on impulse buying.

Research limitations/implications

Findings are limited by the sampling plan, the sample size and the measurement of some of the variables; only one product type is analysed. Further research is needed to confirm that shipping-refund costs and delayed gratification (traditionally, discouraging factors of online buying) encourage online impulse buying; clarify contradictory results regarding the role of online privacy and convenience. This research contributes to the validation of a scale to measure the influence of social media on impulse buying behaviour.

Practical implications

Offline companies can trigger the buying impulse to a greater extent than online retailers. Managers must carefully select social networks to encourage impulse buying, Facebook and Instagram being the most influential; Twitter has the least impact.

Originality/value

This study compares the impulse buying phenomenon in both the physical store and the internet. Moreover, the influence of social networks on impulse buying is also explored.

Este trabajo explora la compra por impulso en el sector de la moda, comparando los canales físico y online para determinar cuál se percibe como más impulsivo.

Diseño/metodología/enfoque

De la revisión de la literatura se extraen tres preguntas de investigación, examinadas a través de una encuesta auto-administrada online con 212 respuestas válidas.

Los resultados muestran que: el canal offline es ligeramente percibido como más impulsivo que el online; los factores motivadores de la compra impulsiva online explican mejor este comportamiento que los desmotivadores; las redes sociales pueden tener un gran impacto en la compra impulsiva.

Limitaciones/implicaciones de la investigación

Las limitaciones radican en el plan de muestreo, el tamaño muestral, y la medición de algunas variables; sólo una industria es analizada. Futuras investigaciones deberán: confirmar que los gastos de envío-devolución, así como la gratificación retrasada (tradicionalmente considerados como motivadores de la compra online) pueden motivar la compra impulsiva online; clarificar resultados contradictorios sobre la privacidad y la conveniencia de Internet. Esta investigación contribuye a la validación de un instrumento para medir la influencia de las redes sociales en la compra impulsiva.

Implicaciones para la gestión

Las tiendas físicas pueden estimular la compra por impulso más que los vendedores online. Los gestores deben seleccionar cuidadosamente las redes sociales para favorece la compra por impulso, siendo Facebook e Instagram las más influyentes; Twitter tiene el menor impacto.

Originalidad/valor

Este estudio compara el fenómeno de la compra impulsiva tanto en el canal físico como online, y explora la influencia de las redes sociales en la compra impulsiva.

- Social networks

- Impulse buying

- Physical store

- Compra impulsiva

- Tienda física

- Motivadores

- Redes sociales

Aragoncillo, L. and Orus, C. (2018), "Impulse buying behaviour: an online-offline comparative and the impact of social media", Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC , Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 42-62. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-03-2018-007

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Laura Aragoncillo and Carlos Orus.

Published in Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original 43 publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The importance of impulse buying in consumer behaviour has been clear for some years. Previous research both in the academic and the professional fields has shown that impulse buying represents between 40 and 80 per cent of all purchases, depending on the type of product ( Amos et al. , 2014 ; Marketingdirecto, 2012 ). Impulse buying has aroused the interest of researchers and organizations which have tried to understand the psychological underpinnings of this behaviour, as well as “impulse temptations”, to boost sales ( Beatty and Ferrell, 1998 , Kacen and Lee, 2002 ; Kacen et al. , 2012 ; Amos et al. , 2014 ).

However, because of the serious impact of the economic crisis and the growing use of the internet as an information search and purchase channel, consumer behaviour seems to have changed towards a more planned and informed process ( Experian Marketing Services, 2013 ; Banjo and Germano, 2014 ). At the same time, several authors claim that the internet indeed favours impulse buying ( Gupta, 2011 ; Rodríguez, 2013 ). Thus, a certain degree of uncertainty now exists about the role of impulse buying, both in the conventional, physical store and the online channel, as well as about which channel encourages this behaviour to a greater extent. Although previous research has addressed the impulse buying phenomenon, focusing either on the physical store or on the internet in isolation, there is a lack of studies analysing both the channels simultaneously.

the consumer’s perceptions about how the internet and the traditional, physical store affects his or her impulse buying behaviour;

which characteristics of the internet, compared to the physical channel, encourage or discourage online impulse buying; and

because of the growing impact of social media on consumer behaviour ( Xiang et al. , 2016 ), the influence of social networks on impulse buying is also explored.

This research is focused on the fashion industry for several reasons. First, a significant proportion of consumers’ purchases are of clothing and shoes ( INE -Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2015 ). Second, online shopping in this industry has been steadily growing during the past years ( CNMC -Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, 2016 ; Eurostat, 2017 ) and this growth is particularly observed in social media ( IAB Spain, 2016 ). Finally, it is one of the industries that IS most prone to impulse buying ( Luna and Bech-Larsen, 2004 ).

2. Literature review

2.1 impulse buying.

The phenomenon of impulse buying was first acknowledged as an irrational behaviour in the decade of the 1940s ( Luna and Quintanilla, 2000 ). This phenomenon aroused the interest of numerous researchers, who thereafter faced the challenge of measuring it: participants in experiments were reluctant or unwilling to overtly declare all the products that they intended to purchase (these were subsequently compared with actual purchases; Kollat and Willett, 1969 ). Even though there is still no consensus in the literature about the definition of the concept ( Amos et al. , 2014 ), this review aims at offering a clear overview of its evolution.

The first studies on impulse buying can be found in the consumer buying habits studies carried out by the Du Pont de Nemours and Co. (1945 / 1949 / 1954 / 1959 / 1965 ; cited in Rook, 1987 ), which focused mainly on understanding how the phenomenon occurred and its extent. Some years after the first studies, the importance of impulse buying was underlined by another study which showed that a considerable percentage of sales in retail stores came from unplanned purchases ( Clover, 1950 ). In this research, an impulse buy was first conceptualized as an unplanned purchase, that is, “the difference between a consumer’s total purchases at the completion of a shopping trip, and those that were listed as intended purchases prior to entering a store” ( Rook 1987 , p. 190).

However, several authors have argued that defining impulse buying only on the basis of unplanned purchases is rather simplistic ( Stern, 1962 ; Kollat and Willett, 1969 ; Rook, 1987 ) and went a step further by arguing that while all impulse purchases can be considered as unplanned, not all unplanned purchases can be considered as impulsive ( Koski, 2004 ). An unplanned purchase may occur simply because the consumer needs to buy a product but it has not been placed on the shopping list in advance. Unplanned purchases are not necessarily accompanied by an urgent desire or strong positive feelings, which are usually associated with an impulse buy ( Amos et al. , 2014 ).

In this way, authors such as Applebaum (1951) , Stern (1962) and Kollat and Willett (1969) , extended the concept by establishing that impulse buying emerged after the exposure to a stimulus. Applebaum (1951 , p. 176) defined it as “buying which presumably was not planned by the customer before entering a store, but which resulted from a stimulus created by a sales promotional device in the store”. However, this definition was also considered limited, given that the stimulus that provoked the impulse was exclusively a sales promotion device. On the other hand, Stern (1962) distinguished four types of impulsive buying: pure impulse buying totally breaks the normal buying pattern. It occurs when the consumer has no purchase intention but the product elicits emotions that eventually lead to the act of buying; reminder impulse buying occurs when the consumer sees an item and remembers that the stock at home is low, or recalls an advertisement or other information about the product and a previous wish to purchase it; suggestion impulse buying takes place when the consumer sees an item for the first time and detects a need that it can satisfy; and planned impulse buying occurs when the consumer enters the store with the intention to purchase some specific products, but also expects to make other purchases depending on the special offers and promotions that he or she finds at the store.

The contribution of Rook to the literature had a significant impact on the conceptualization of the term ( Rook and Hoch, 1985 ; Rook, 1987 ; Rook and Fisher, 1995 ). This author affirmed that:

[…] impulse buying occurs when a consumer experiences a sudden, often powerful and persistent urge to buy something immediately. The impulse to buy is hedonically complex and may stimulate emotional conflict. Also, impulse buying is prone to occur with diminished regard for its consequences ( Rook, 1987 , p. 191).

Further investigations focused on the study of consumer behaviour in the buying decision process with the goal of identifying factors, both internal (related to personal characteristics) and external (related to situational – store and product – characteristics) that affect impulse buying ( Amos et al. , 2014 ; Muruganantham and Bhakat, 2013 ; Badgaiyan and Verma, 2014 ). Previous studies emphasized that impulse buying was primarily affective in nature, wherein the hedonic and emotional aspects of these purchases determine consumer behaviour to a greater extent than the utilitarian and rational aspects ( Luna and Quintanilla, 2000 ). Recently, impulse buying has been defined as “a sudden, compelling, hedonically complex purchase behavior in which the rapidity of the impulse purchase decision precludes any thoughtful, deliberate consideration of alternatives or future implications” ( Sharma et al. , 2010 , p. 277).

2.2 Online impulse buying

There is a need to study impulse buying on the internet, because of the increasing importance of this medium as a sales channel. According to Google Consumer Barometer (2015) and Eurostat (2017) , around two-thirds of the European population makes online purchases. If we focus on the fashion industry, clothing and sport garments were the bestselling categories in Europe in 2016 ( Eurostat, 2017 ).

One may argue that online buying behaviour is rather rational, as the consumer tends to search for information and make comparisons before making the final decision. However, rational choices are not always made, and impulsive buying also has room in this medium ( Jeffrey and Hodge, 2007 ; Verhagen and van Dolen, 2011 ). Taking into account the importance of impulse buying for companies’ revenues, it would appear worthwhile to investigate this phenomenon in the online channel.

In the late 1980s, it was acknowledged that impulse buying had become easier because of innovations such as credit cards, direct marketing and in-home shopping ( Rook, 1987 ). The ease of choosing a product and “clicking” on it may create temptation and thus increase the likelihood of impulse buying ( Greenfield, 1999 ). Other authors argue that the internet may lessen consumers’ capacity to control their buying impulses. LaRose (2001) found that the characteristics of the internet that empowered consumers to control their buying impulses were few (13), compared to those that weakened such control (50). On the other hand, other authors state that consumers carry out less impulse purchases online than offline ( Kacen, 2003 ). In fact, most research on e-commerce has considered online purchase decisions as rational processes, based on problem solving and information processing ( Verhagen and van Dolen, 2011 ). In the specific context of this research, McCabe and Nowlis (2003) indicate that products for which touch is important, such as clothing, are more impulsively acquired at physical stores than online, given that the internet prevents consumers from touching and trying on the garments.

The evolution of the internet to the 2.0 Web has dramatically changed the way in which consumers and companies interact and carry out transactions. Specifically, it has been noted that social commerce is as branch of e-commerce which incorporates the use of social media in all kinds of commercial activities ( Xiang et al. , 2016 ). In this sense, 65 per cent of social media users affirm that social networks influence their shopping processes, and almost half of them say that social media inspire their online purchases ( IAB Spain, 2016 ; PWC, 2016 ). Previous research has shown that consumers are influenced by others at the time of buying a product, and this influence may be higher online than offline ( Riegner, 2007 ). Therefore, social media can represent a powerful tool to boost impulse buying.

3. Research questions

Which channel – online or offline – is considered by the consumer as leading to more impulse buying?

Which factors encourage and discourage online impulse buying?

What is the influence of social networks on impulsive buying?

Table I summarizes the conceptual framework that attempts to address the research questions.

3.1 Impulsiveness of the online versus offline channel (RQ1)

On the one hand, authors such as Greenfield (1999) and LaRose (2001) argue that the online channel can lead to more impulse buying than the offline channel: the greater product assortment, the possibility of making purchases 24/7 from any location and the use of advanced marketing techniques based on personalization, have the capacity to encourage online shopping to a greater extent than other factors, such as delayed possession or shipping costs, that might discourage it. Furthermore, despite the fact that the internet prevents consumers from touching and trying on garments ( McCabe and Nowlis, 2003 ), this limitation can be overcome by good quality product presentation, with realistic pictures and detailed information about sizes and measures. Offering the possibility of free shipping or in-store refunds can also be used to overcome the limitations of online shopping.

On the other hand, the capacity of physical stores to create sensory experiences, as well as the store’s atmosphere, can lead the physical channel to be more impulsive than the online channel ( Gupta, 2011 ). The previous literature review has pointed out that impulse buying is hedonically complex and has a strong emotional character ( Luna and Quintanilla, 2000 ; Sharma et al. , 2010 ). Emotions and hedonic experiences are strongly related to sensory stimulation ( Krishna, 2012 ). To the extent that physical stores are able to stimulate the senses better than the internet, we might expect that consumers will perceive the physical channel as more impulsive than the online channel. A recent report by Kearney (2013) revealed that 40 per cent of the participants in a survey (3,000 consumers from the USA and the UK) spent more money than planned in physical stores, while the percentage doing so in the online channel was 25 per cent.

Finally, several authors argue that, beyond channel characteristics, personal and situational characteristics also determine impulse buying ( Badgaiyan and Verma, 2014 ; Lim and Yazdanifard, 2015 ). Sociodemographic variables, such as gender or age, can strongly affect behaviour ( Youn and Faber, 2000 ). As we noted in our introduction, the economic crisis of the past years may have changed consumer behaviour and the way they use new technologies, pivoting in general towards more planned purchases.

3.2 Encouraging and discouraging factors for online impulse buying (RQ2)

The literature review also reveals differentiating characteristics of the online and the offline channels that can encourage or discourage impulse buying ( Table I ). Among the encouraging factors with regard to online impulse buying, we find the following defining characteristics of the internet: greater product assortment and variety, sophisticated marketing techniques, credit cards, anonymity, lack of human contact and easy access and convenience. First, greater assortment and product variety is one of the most influential factors for online consumers in carrying out impulse purchases ( Brohan, 2000 ; Chen-Yu and Seock, 2002 ). Online stores have the capacity to offer greater assortment and variety than physical stores, which are more limited by physical constraints.

Regarding the second factor, the use of advanced marketing techniques, such as personalized emails based on purchasing history or with information about new products and a direct link to the electronic store, can be highly effective in encouraging online impulse buying ( Koufaris, 2002 ; LaRose, 2001 ). Sales promotions devices, though they are also available at physical stores, seem to be more effective in online shopping. In the virtual environment, the possibilities for multisensory stimulation are limited and sales promotions and offers more easily grab consumers’ attention ( Kacen, 2003 ). Furthermore, online promotions can be more customized than offline promotions, so consumers will be more likely to be offered products of specific, personal interest ( Koski, 2004 ).

Third, credit cards can encourage impulse buying ( Karbasivar and Yarahmadi, 2011 ; Koski, 2004 ). This payment method is commonly used in offline purchases, but it is more widespread in the online channel. Consequently, use of the online channel could encourage more impulse buying than the offline channel. When using virtual payment methods, money appears less real and consumers have the feeling that they are not really spending it ( Dittmar and Drury, 2000 ; Tuttle, 2014 ). Thus, the monetary consequences of making (impulse) purchases are not perceived immediately ( LaRose, 2001 ).

The anonymity and lack of human contact that the internet provides can also encourage online impulse buying. According to Rook and Fisher (1995) , impulse buying is more likely to occur when the situation assures anonymity, so this characteristic may be an important advantage of the internet over the physical store. Consumers may feel more comfortable buying online those products which would make them feel embarrassed if purchased offline ( Koufaris, 2002 ). Similarly, we may state that, by and large, online consumers carry out their purchases alone and in private; if the purchase is made offline, it is common to have physical contact and interaction with other people (salespeople, companions). Taking into account that human contact leads to a better control of the impulse to buy ( Greenfield, 1999 ), its absence may encourage impulse buying on the internet.

Finally, buying at physical stores is limited to a geographic location and to opening hours; on the internet, these limitations disappear ( Koufaris, 2002 ). Furthermore, access to an online store does not entail any cost or effort on the part of the consumer (transportation, parking, etc.), so the probability of a spontaneous visit, with no initial purchase plan but ending up in an impulse buy, is higher online than offline ( Moe and Fader, 2004 ). Also, consumers browsing online are constantly exposed to products that they might like, even though they are not intentionally searching for them, or plan to purchase them; and buying these items is only one click away. This ease of completing transactions can lead to more impulse buying than in the physical channel ( Dawson and Kim, 2009 ; Koski, 2004 ; Koufaris, 2002 ).

Regarding the discouraging factors for online impulse buying, the specialized literature identifies the following: delayed satisfaction or gratification, the impossibility of using the five senses, easy comparisons, shipping and refund costs and easy access and convenience ( Table I ). One of the defining elements of impulse buying is the urgent need to possess the product; immediate possession provides satisfaction and encourages impulse buying ( Rook, 1987 ; LaRose, 2001 ). Consumers have to wait for product delivery when buying online (in the context of physical goods), and this time lapse can deter them from carrying out impulse buying ( Kacen, 2003 ; Koski, 2004 ).

Impulse buying is the result of seeing, touching, hearing, smelling and/or tasting ( Underhill, 2009 ). However, the internet does not have the same capacity to stimulate the five senses as does the physical store, and therefore, the online channel can be less encouraging of impulsive buying than the offline channel ( Kacen, 2003 ; Koski, 2004 ). Online stores can only stimulate sound and sight, but they cannot do anything (at the moment) to appeal to the other senses. This can be especially important in the context of clothing, where touch is a fundamental sense that can trigger impulse buying ( Peck and Childers, 2006 ).

The ease with which consumers can make comparisons online, and the existence of shipping and/or refund costs, can also discourage online impulse buying. The internet allows consumers to easily compare products and prices before making the purchase decision ( Brohan, 2000 ; LaRose, 2001 ; Koski, 2004 ). In addition, one of the most important deterrent factors for online shopping is the cost of shipping and refunding merchandise ( Kukar-Kinney and Close, 2010 ). Consumers try to avoid these costs as much as possible. Therefore, high shipping and refund costs can restrain their buying impulse.

Finally, easy access and convenience, while previously described as an encouraging factor, may also be considered a discouraging factor. When the consumer carries out his or her shopping in a physical store, he or she may more readily follow the impulse to make the purchase to avoid the costs involved in returning to the store to make the purchase later. In the online environment, coming back to the store does not entail much effort, and consumers may better control their impulses and thus delay their purchase decision ( Moe and Fader, 2004 ).

3.3 The role of social networks in impulse buying behaviour (RQ3)

RQ3 explores the influence of social networks on impulse buying behaviour in the fashion industry (clothing, shoes and accessories). Social media strongly affect individuals’ behaviours, and particularly consumer behaviour ( IAB Spain, 2016 ). Social media users share a wide spectrum of experiences, ranging from what they are in the mood to do that day, to vigorously evaluating the products and services they consume ( Anderson et al. , 2011 ). This behaviour is leading consumers to influence others, through sharing pictures of their purchases and offering recommendations. These actions can stimulate unplanned and impulse buying ( Xiang et al. , 2016 ). Furthermore, recommendations and opinions not only affect buying behaviours but also help to build favourable brand images, which also stimulate impulse buying ( Kim and Johnson, 2016 ).

Thus, we may expect that consumers will use information from social media to gain ideas that can subsequently turn into purchase actions; after seeing a garment on social media, the consumer may also search for it and buy it either online or at a physical store. Moreover, previous research reveals that because of recommendations and photographs showing purchases in social media, information coming from other consumers is the most influential factor on consumer behaviour ( Anderson et al. , 2011 ; Xiang et al. , 2016 ). Therefore, this research explores whether users use social media as a tool to inspire their purchases. At this point, it is important to note that the photograph or recommendation shared by a consumer must represent an external stimulus that motivates the impulse buying. That is, the recommendation is not a piece of information that the consumer has been considering as part of his or her product research (within a planned purchase decision process), but it is a stimulus that triggers the desire to acquire the product without further deliberation.

Also, we aim at identifying which social networks affect impulse buying to a greater extent. This knowledge would help fashion brand companies in their commercial strategies. Specifically, we focus on the four social networks with the highest penetration rates and which could therefore have the greatest impact on the fashion industry ( AIMC -Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación, 2016 ; IAB Spain, 2016 ): Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.

4.1 Data collection procedure

We conducted an online self-administered survey to address the research questions. The sampling procedure consisted of a non-probabilistic, convenience sampling method ( Malhotra and Birks, 2007 ), obtaining a total of 243 questionnaires. The survey was structured in five sections. In the first section, introductory questions were asked regarding the participants’ fashion product preferences and how frequently they bought clothing. The second section gathered information about their impulse buying behaviour, both in the offline channel and in the online channel (participants only answered the online-channel questions if they had ever made any online purchase in the product category). If the participants declared that they had made online purchases of clothing, shoes and/or accessories, they answered the third block of questions regarding their perceptions about the encouraging and discouraging factors associated with online impulse buying. The participants who were users of social networks (regardless of the previous section) were asked about their influence on their shopping behaviour. The fifth and last section gathered the participants’ sociodemographic information (age, gender, occupation and their experiences with the internet, social networks and online shopping).

4.2 Measurement instruments

The majority of the variables were measured using scales validated in prior studies, with minor modifications to ensure contextual consistency. The Appendix shows the full list of items used in the survey, together with the references used to measure impulse buying (both online and offline) as well as the encouraging and discouraging factors for online impulse buying. However, the items related to the influence of social networks were developed for this present research, as we found no appropriate scale in the literature. All the items used seven-point Likert scales. In addition, the section about the use of social networks asked participants whether or not they were users of the four networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest). If they were users, the participant indicated whether he or she had ever seen a garment in that social network and felt the need to buy it (1 = yes, 0 = no), as well as the probability of using it to carry out purchases (1 = not at all likely; 7 = very likely).

4.3 Sample characteristics

Once the sample was refined by screening out questionnaires with mistakes and inconsistencies, the final valid sample consisted of 212 participants. We used IBM SPSS software (v22) to analyse the data. The characteristics of the sample appear in Table II . It should be noted that, through the convenience nature of the sample, we were satisfied with the sample profile because it showed similarities to recent studies about the use of the internet and e-commerce ( AIMC -Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación, 2016 ; ONTSI -Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información, 2016 ), with the exception of gender. The majority of participants in the survey were female ( Table II ). Although this consumer segment has been widely used in research about the fashion industry ( Luna and Bech-Larsen, 2004 ; Lee and Kim, 2008 ), this imbalance represents a limitation of the current study.