BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Discussion of students' e-book reading intention with the integration of theory of planned behavior and technology acceptance model.

- Business School, Guilin University of Technology, Guilin, China

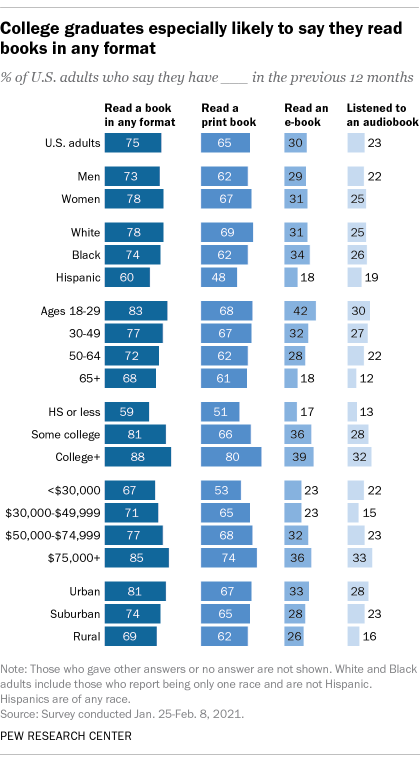

The emergence of e-books with the characteristics of easy access and reading any time anywhere is a subject of debate in academia. Topics include the use of e-books in libraries, their use in support teaching, new possibilities for reading activities, potential uses for library archives, and the motivation and intention of e-book users. Students at Guilin University of Technology participated in a survey. Of the 300 copies of the questionnaire distributed, 263 valid copies were returned, a retrieval rate of 88%. The research results show that (1) Usability and reading need are the key factors in e-book usage. Usability refers to convenient keyword searches, portability, and any time reading. E-books are considered to make searching and reading large amounts of data easier. (2) E-books are not restricted to time and space so that the overall reading quantity is increasing. Readers become accustomed to reading e-books, and the quality of their digital reading is gradually enhanced. (3) Students should complete e-book use courses offered by libraries to enhance their familiarity with e-books and their use of e-book software, thereby enhancing postgraduate student readers' e-book information literacy. The results of the research prompt suggestions to enhance the promotion of reading and e-book information to encourage student readers' e-book reading intention.

Introduction

In the rapidly developing information era, the value of e-books gradually became apparent. The portability of e-books has been an attraction ever since their first appearance. In the field of library and information science, e-books were much discussed. Some argued that e-books should not only be used in the library but should also enhance the services that libraries provide and should be used to support teaching. Susantini et al. (2021) mentioned that it was remarked that e-books can be a new approach to reading and can change how and when people use libraries. As digital publishing expanded, libraries began to acquire significant amounts of digital products allowing users to search digital documents in a convenient and suitable manner. Almost not a country or region in the world could escape from the pandemic of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). The pandemic results in major changes in human life to change life and learning styles. Mass or national school closure is preceded in many countries or regions this year in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 ( Viner et al., 2020 ). To cope with the pandemic, the approach of “Learning never stops” allows students continuing the learning with the minimal impact. Nevertheless, in face of the menacing pandemic, most teachers passively adopt distance courses without advance warning or enough time for preparing courses ( Almekhlafi, 2021 ). Although distance education presents various advantages and is limited to time and location ( Karakoç Öztürk, 2021 ), the practice of distance education is the maximal transformation. A lot of countries in the world, and even schools, temporarily practice or promote distance education. It would have the frontline teachers and students face some problems or difficulties. Current academic discussions on temporary promotion of distance learning are limited, while the use of e-books is inevitable for the promotion of distance education. The rise in digital publishing led to a situation where there are more e-books than printed books ( Erkayhan and Ulke, 2017 ). This fact is challenging for libraries, especially university libraries, where a gradual transition occurred from paper-based collections to digital resources. Users of university libraries tend to have specific needs, and building a suitable collection can be difficult. Although libraries have started to value the development of their digital collections, they lack information on readers' acceptance, requirements, usage time, and reading habits. They are unsure if readers will change their reading habits and their requirements for printed books after e-books have been introduced into libraries. This is an area worthy of discussion when libraries are compiling their collections. Therefore, the integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was used in this research to investigate students' reading intention toward e-books. Understanding how readers use the collections in the libraries and assessing how their expectations are being met might improve students' reading literacy of printed books and e-books. New insights could help to promote students' reading services.

Literature Review

Digital reading behavior.

In their survey of digital reading behavior, Huang and Chang (2019) found that frequent e-book reading locations included rooms at home, especially the living room, offices, schools, and on transport to work. In different situations, the most common types of e-book reading were: “business and finance,” “literature and fiction,” “tourism and sport,” “lifestyle and hobbies,” and “fashion and entertainment.” While at home, readers mainly read e-books on tablets, and they use smartphones while commuting. Regarding reading habits, 60% of respondents read 1–4 e-books a month, and about 50% of respondents read e-books for an average of 16–30 min each time. In the survey, more than 70% of the respondents were satisfied with their e-book reading experience. Leong et al. (2019) discovered that most readers read e-books on tablets, read at home, and read every week and that reading methods depend on the type of books. In terms of the effect of e-books on readers, readers' knowledge of e-books was related to the reading experience. Readers favored the convenience of e-books, but they were used to reading paper books. Ease of use of software and hardware and readers' reading habits were the key factors in reading intention. Reading e-books changed reading habits, such as searching for books, type of reading material, time spent reading, note-taking habits, frequency of repeated reading, and book sharing behavior. Readers' problems with e-books included installation, searching, and reading, with searching as the biggest problem. Readers' needs for e-books resulted in bigger collections and longer recommendation book lists. The need arose for reading software to improve searching and personalization.

Application of Model

Kaushik and Rahman (2017) revealed that the use of the TAM to predict users' behavioral intention in using new technologies and their real-use behavior was supported by a significant body of empirical research. However, two factors, the social factor and the controlling factor, which were proven to significantly affect users' real-use behavior with new technologies, were not included in the model. These two factors were the key variables in the TPB. Wei et al. (2017) integrated the TAM and the TPB, including a subjective norm and perceived behavioral control in the TAM, proposing a combined TAM and TPB (C-TAM-TPB), and they conducted empirical research on students' use behavior of computing resource centers.

The empirical results of the study by Lee and Cranage (2018) revealed that the C-TAM-TPB, integrating the TAM and the TPB, presented a high level of fit in explaining users' use behavior with new technologies. Moreover, the group analysis of users with different use experiences revealed that C-TAM-TPB presented a good fit for users with or without experience. Therefore, in this study, TPB and TAM are integrated to discuss students' e-book reading intention.

Research Hypothesis

Lee (2017) stated that Davis included the belief—attitude—intention—behavior relation in the theory of reasoned action in the TAM and particularly emphasized the importance of “perceived usefulness” and “perceived ease of use.” Davis considered that information technology with higher ease of use in situations with comparable tasks could assist an individual in completing more tasks in the same time, further enhancing individual work performance. In this case, the perceived ease of use could reinforce the perceived usefulness to the individual of information technology. Stouthuysen et al. (2018) mentioned that Davis also considered that users might have a negative attitude toward specific information technology but would still be willing to use the technology when its use is perceived to enhance personal work performance. Ko (2017) indicated that perceived usefulness could indirectly affect the use intention of information technology through attitude and could directly affect the behavioral intention of users. Furthermore, in addition to perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as major factors in the attitudes of users toward information technology, attitudes would further affect the behavioral intention of users, thereby determining the acceptance and use behavior of information technology.

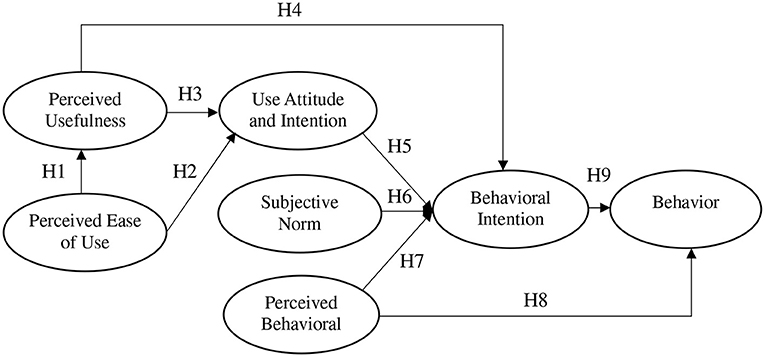

The following hypotheses are therefore established in this study.

H1: Perceived ease of use presents positive and direct effects on perceived usefulness.

H2: Perceived ease of use shows positive and direct effects on attitude.

H3: Perceived usefulness reveals positive and direct effects on attitude.

H4: Perceived usefulness shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention.

H5: Attitude shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention.

H6: Subjective norm reveals positive and direct effects on behavioral intention.

H7: Perceived behavioral control shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention.

H8: Perceived behavioral control presents positive and direct effects on behavior.

H9: Behavioral intention reveals positive and direct effects on behavior.

Methodology

Conceptual structure.

The integration of the TAM and the TPB is used to construct the model in this study, as shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1 . Conceptual structure.

Research Subject and Analysis Method

Five hundred copies of a questionnaire were distributed to university students in Guilin, China. A total of 433 valid copies were returned, a retrieval rate of 87%. AMOS software was used as the data analysis tool to evaluate students' e-book reading intention.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results show that convergent validity in the observation model could observe the suggested reliability value of individual observed variables, construct reliability (CR), and average variances extracted (AVE), where the reliability of individual observed variables is suggested as higher than 0.5. The factor loadings of various observed variables in this study are higher than the suggested value. A CR value of higher than 0.6 is preferable, but some researchers suggest that it should be higher than 0.5. The estimation result of the model shows that the CR is higher than 0.5. The average variance extracted should be higher than 0.5. The average variance extracted of dimensions in this study is higher than 0.5, conforming to the suggested value.

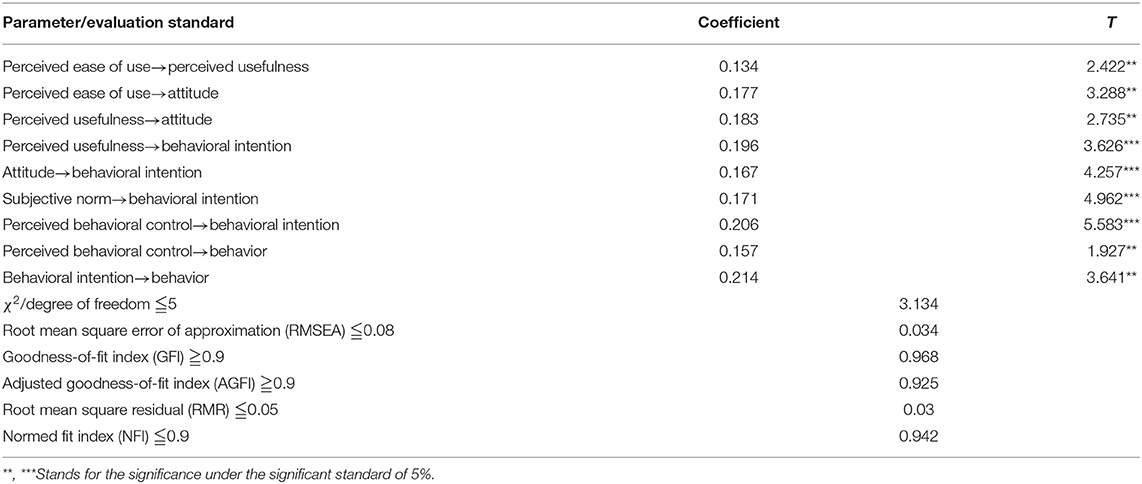

The estimation results of the structural equation are shown in Table 1 . First, the suggested standards for X 2 /df, RMSEA, GFI, AGFI, RMR, and NFI are ≦ 5, ≦ 0.08, ≧ 0.9, ≧ 0.9, ≦ 0.05, and ≧ 0.9, respectively. The values in this study appear as X 2 /df = 3.134 ≦ 5, RMSEA = 0.034 ≦ 0.08, GFI = 0.968 ≧ 0.9, AGFI = 0.925 ≧ 0.9, RMR = 0.03 ≦ 0.05, and NFI = 0.942 ≧ 0.9, revealing good overall fit. As a result, the estimation results of the structural equation ( Table 1 ) show that all parameters achieve the significant standards ( p < 0.05).

Table 1 . Structural equations model result.

From the above estimation results of the structural equations, the following seven research hypotheses in this study are supported: H1: Perceived ease of use presents positive and direct effects on perceived usefulness; H2: Perceived ease of use shows positive and direct effects on attitude; H3: Perceived usefulness reveals positive and direct effects on attitude; H4: Perceived usefulness shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention; H5: Attitude shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention; H6: Subjective norm reveals positive and direct effects on behavioral intention; and H7: Perceived behavioral control shows positive and direct effects on behavioral intention.

Most e-books are free and easy to access. Therefore, students tend to read quickly and to immediately reject unsuitable e-books and to search for the next one. In the reading process of acquisition and searching, e-books usually show an abstract on the interface indicating the content and facilitating the elimination of unsuitable books or articles. Printed books do not often show abstracts, and the content is only indicated by the cover. Students appear to have a higher acceptance of e-books and to have definite reading goals, thereby increasing reading frequency. Furthermore, students generally appreciate the convenience of keyword searches of e-books, discovering new reading strategies involving integration and explanation. Students tend to read printed books for comprehension and to use keywords to directly search for solutions in e-books. It seems that an increasing number of students are engaging in digital reading for academic purposes.

The research results reveal students' high demands for reading e-books. The convenience of not being restricted to time and space is popular among students when considering the importance of e-books. The results show that students are not familiar with e-book resources and how to use them, and that digital reading can be limited by software and hardware issues. In addition, note-taking can be challenging because of the unfamiliar interface. Therefore, students should participate actively in the e-book use education courses offered by libraries to increase their understanding of e-books and to improve their ability to use e-book reading software to enhance their e-book information literacy. Students encounter many difficulties in the digital reading experience, including the limitations of software and hardware, the challenges involved in underlining and making notes, and the unfriendly user interface. Students expressed the view that unstable software or hardware might hinder their e-book reading. E-book firms could improve the stability of software and hardware, thereby enhancing students' use satisfaction. It is therefore suggested that e-book firms should regularly survey readers' digital reading experiences and improve the e-book service to increase students' e-book use intention.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The present study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of the Guilin University of Technology, with written informed consent being obtained from all the participants. The research protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Guilin University of Technology.

Author Contributions

Y-ZL performed the initial analyses and wrote the manuscript. Y-MX was responsible for the methodology, software, and validation. Y-YM and CL assisted in the data collection and data analysis. All authors revised and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region: 100 Plan on the Introduction of High-level Overseas Talents for Colleges and Universities in Guangxi (YM 20181204).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their valuable comments.

Almekhlafi, A. G. (2021). The effect of e-books on preservice student teachers' achievement and perceptions in the united arab emirates. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 1001–1021. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10298-x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Erkayhan, S., and Ulke, Y. B. (2017). Digitalization of the book publishing industry. A study on the e-book publishing in Turkey. Online Commun. Media Technol. 7, 61–78. doi: 10.29333/ojcmt/2610

Huang, H. L., and Chang, L. H. (2019). Implementing English as a medium of instruction to promote English learning of sixth graders. Proc. CEBC . 78–91.

Google Scholar

Karakoç Öztürk, B. (2021). Digital Reading and the Concept of Ebook: Metaphorical Analysis of Preservice Teachers' Perceptions Regarding the Concept of Ebook . Adana: Sage Open.

Kaushik, A. K., and Rahman, Z. (2017). An empirical investigation of tourist's choice of service delivery options-SSTs vs. service employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manag . 29, 1892–1913. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-08-2015-0438

Ko, C. H. (2017). Exploring how hotel guests choose self-service technologies over service staff. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 9, 16–27.

Lee, B., and Cranage, D. A. (2018). Causal attributions and overall blame of self-service technology (SST) failure: Different from service failures by employee and policy. J. Hospitality Market Manag . 27, 61–84. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2017.1337539

Lee, H. J. (2017). Personality determinants of need for interaction with a retail employee and its impact on self-service technology (SST) usage intentions. J. Res. Interact Market. 11, 214–231. doi: 10.1108/JRIM-04-2016-0036

Leong, A. C. H., Abidin, M. J. Z., and Saibon, J. (2019). Learners' perceptions of the impact of using digital storytelling on vocabulary learning. Teach. Engl. Technol. 19, 3–26.

Stouthuysen, K., Teunis, I., Reusen, E., and Slabbinck, H. (2018). Initial trust and intentions to buy: the effect of vendor-specific guarantees, customer reviews and the role of online shopping experience. Elect. Commerce Res. Appl. 27, 23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2017.11.002

Susantini, E., Puspitawati, R.P., and Suaidah, H. L. (2021). e-book of metacognitive learning strategies: design and implementation to activate student's self-regulation. Res. Prac. Technol. Enhanced Learn 16:13 doi: 10.1186/s41039-021-00161-z

Viner, R. M., Russell, S. J., Croker, H., Packer, J., Ward, J., Stansfield, C., Bonell, C., and Booy, R. (2020). School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolescent Health 4, 397–404. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wei, W., Torres, E. N., and Hua, N. (2017). The power of self-service technologies in creating transcendent service experiences: the paradox of extrinsic attributes. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manag. 29, 1599–1618. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2016-0029

Keywords: theory of planned behavior, technology acceptance model, e-book, reading intention, behavioral intention

Citation: Luo Y-Z, Xiao Y-M, Ma Y-Y and Li C (2021) Discussion of Students' E-book Reading Intention With the Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Technology Acceptance Model. Front. Psychol. 12:752188. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.752188

Received: 02 August 2021; Accepted: 25 August 2021; Published: 20 September 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Luo, Xiao, Ma and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chao Li, walking_lee@163.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2022

A systematic review on digital literacy

- Hasan Tinmaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4310-0848 1 ,

- Yoo-Taek Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1913-9059 2 ,

- Mina Fanea-Ivanovici ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2921-2990 3 &

- Hasnan Baber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8951-3501 4

Smart Learning Environments volume 9 , Article number: 21 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

48k Accesses

39 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The purpose of this study is to discover the main themes and categories of the research studies regarding digital literacy. To serve this purpose, the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier were searched with four keyword-combinations and final forty-three articles were included in the dataset. The researchers applied a systematic literature review method to the dataset. The preliminary findings demonstrated that there is a growing prevalence of digital literacy articles starting from the year 2013. The dominant research methodology of the reviewed articles is qualitative. The four major themes revealed from the qualitative content analysis are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and digital thinking. Under each theme, the categories and their frequencies are analysed. Recommendations for further research and for real life implementations are generated.

Introduction

The extant literature on digital literacy, skills and competencies is rich in definitions and classifications, but there is still no consensus on the larger themes and subsumed themes categories. (Heitin, 2016 ). To exemplify, existing inventories of Internet skills suffer from ‘incompleteness and over-simplification, conceptual ambiguity’ (van Deursen et al., 2015 ), and Internet skills are only a part of digital skills. While there is already a plethora of research in this field, this research paper hereby aims to provide a general framework of digital areas and themes that can best describe digital (cap)abilities in the novel context of Industry 4.0 and the accelerated pandemic-triggered digitalisation. The areas and themes can represent the starting point for drafting a contemporary digital literacy framework.

Sousa and Rocha ( 2019 ) explained that there is a stake of digital skills for disruptive digital business, and they connect it to the latest developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud technology, big data, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The topic is even more important given the large disparities in digital literacy across regions (Tinmaz et al., 2022 ). More precisely, digital inequalities encompass skills, along with access, usage and self-perceptions. These inequalities need to be addressed, as they are credited with a ‘potential to shape life chances in multiple ways’ (Robinson et al., 2015 ), e.g., academic performance, labour market competitiveness, health, civic and political participation. Steps have been successfully taken to address physical access gaps, but skills gaps are still looming (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010a ). Moreover, digital inequalities have grown larger due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they influenced the very state of health of the most vulnerable categories of population or their employability in a time when digital skills are required (Baber et al., 2022 ; Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ).

The systematic review the researchers propose is a useful updated instrument of classification and inventory for digital literacy. Considering the latest developments in the economy and in line with current digitalisation needs, digitally literate population may assist policymakers in various fields, e.g., education, administration, healthcare system, and managers of companies and other concerned organisations that need to stay competitive and to employ competitive workforce. Therefore, it is indispensably vital to comprehend the big picture of digital literacy related research.

Literature review

Since the advent of Digital Literacy, scholars have been concerned with identifying and classifying the various (cap)abilities related to its operation. Using the most cited academic papers in this stream of research, several classifications of digital-related literacies, competencies, and skills emerged.

Digital literacies

Digital literacy, which is one of the challenges of integration of technology in academic courses (Blau, Shamir-Inbal & Avdiel, 2020 ), has been defined in the current literature as the competencies and skills required for navigating a fragmented and complex information ecosystem (Eshet, 2004 ). A ‘Digital Literacy Framework’ was designed by Eshet-Alkalai ( 2012 ), comprising six categories: (a) photo-visual thinking (understanding and using visual information); (b) real-time thinking (simultaneously processing a variety of stimuli); (c) information thinking (evaluating and combining information from multiple digital sources); (d) branching thinking (navigating in non-linear hyper-media environments); (e) reproduction thinking (creating outcomes using technological tools by designing new content or remixing existing digital content); (f) social-emotional thinking (understanding and applying cyberspace rules). According to Heitin ( 2016 ), digital literacy groups the following clusters: (a) finding and consuming digital content; (b) creating digital content; (c) communicating or sharing digital content. Hence, the literature describes the digital literacy in many ways by associating a set of various technical and non-technical elements.

- Digital competencies

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.1.), the most recent framework proposed by the European Union, which is currently under review and undergoing an updating process, contains five competency areas: (a) information and data literacy, (b) communication and collaboration, (c) digital content creation, (d) safety, and (e) problem solving (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ). Digital competency had previously been described in a technical fashion by Ferrari ( 2012 ) as a set comprising information skills, communication skills, content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills, which later outlined the areas of competence in DigComp 2.1, too.

- Digital skills

Ng ( 2012 ) pointed out the following three categories of digital skills: (a) technological (using technological tools); (b) cognitive (thinking critically when managing information); (c) social (communicating and socialising). A set of Internet skill was suggested by Van Deursen and Van Dijk ( 2009 , 2010b ), which contains: (a) operational skills (basic skills in using internet technology), (b) formal Internet skills (navigation and orientation skills); (c) information Internet skills (fulfilling information needs), and (d) strategic Internet skills (using the internet to reach goals). In 2014, the same authors added communication and content creation skills to the initial framework (van Dijk & van Deursen). Similarly, Helsper and Eynon ( 2013 ) put forward a set of four digital skills: technical, social, critical, and creative skills. Furthermore, van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ) built a set of items and factors to measure Internet skills: operational, information navigation, social, creative, mobile. More recent literature (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) divides digital skills into seven core categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

It is worth mentioning that the various methodologies used to classify digital literacy are overlapping or non-exhaustive, which confirms the conceptual ambiguity mentioned by van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ).

- Digital thinking

Thinking skills (along with digital skills) have been acknowledged to be a significant element of digital literacy in the educational process context (Ferrari, 2012 ). In fact, critical thinking, creativity, and innovation are at the very core of DigComp. Information and Communication Technology as a support for thinking is a learning objective in any school curriculum. In the same vein, analytical thinking and interdisciplinary thinking, which help solve problems, are yet other concerns of educators in the Industry 4.0 (Ozkan-Ozen & Kazancoglu, 2021 ).

However, we have recently witnessed a shift of focus from learning how to use information and communication technologies to using it while staying safe in the cyber-environment and being aware of alternative facts. Digital thinking would encompass identifying fake news, misinformation, and echo chambers (Sulzer, 2018 ). Not least important, concern about cybersecurity has grown especially in times of political, social or economic turmoil, such as the elections or the Covid-19 crisis (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

Ultimately, this systematic review paper focuses on the following major research questions as follows:

Research question 1: What is the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers?

Research question 2: What are the research methods for digital literacy related papers?

Research question 3: What are the main themes in digital literacy related papers?

Research question 4: What are the concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers?

This study employed the systematic review method where the authors scrutinized the existing literature around the major research question of digital literacy. As Uman ( 2011 ) pointed, in systematic literature review, the findings of the earlier research are examined for the identification of consistent and repetitive themes. The systematic review method differs from literature review with its well managed and highly organized qualitative scrutiny processes where researchers tend to cover less materials from fewer number of databases to write their literature review (Kowalczyk & Truluck, 2013 ; Robinson & Lowe, 2015 ).

Data collection

To address major research objectives, the following five important databases are selected due to their digital literacy focused research dominance: 1. WoS/Clarivate Analytics, 2. Proquest Central; 3. Emerald Management Journals; 4. Jstor Business College Collections; 5. Scopus/Elsevier.

The search was made in the second half of June 2021, in abstract and key words written in English language. We only kept research articles and book chapters (herein referred to as papers). Our purpose was to identify a set of digital literacy areas, or an inventory of such areas and topics. To serve that purpose, systematic review was utilized with the following synonym key words for the search: ‘digital literacy’, ‘digital skills’, ‘digital competence’ and ‘digital fluency’, to find the mainstream literature dealing with the topic. These key words were unfolded as a result of the consultation with the subject matter experts (two board members from Korean Digital Literacy Association and two professors from technology studies department). Below are the four key word combinations used in the search: “Digital literacy AND systematic review”, “Digital skills AND systematic review”, “Digital competence AND systematic review”, and “Digital fluency AND systematic review”.

A sequential systematic search was made in the five databases mentioned above. Thus, from one database to another, duplicate papers were manually excluded in a cascade manner to extract only unique results and to make the research smoother to conduct. At this stage, we kept 47 papers. Further exclusion criteria were applied. Thus, only full-text items written in English were selected, and in doing so, three papers were excluded (no full text available), and one other paper was excluded because it was not written in English, but in Spanish. Therefore, we investigated a total number of 43 papers, as shown in Table 1 . “ Appendix A ” shows the list of these papers with full references.

Data analysis

The 43 papers selected after the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively, were reviewed the materials independently by two researchers who were from two different countries. The researchers identified all topics pertaining to digital literacy, as they appeared in the papers. Next, a third researcher independently analysed these findings by excluded duplicates A qualitative content analysis was manually performed by calculating the frequency of major themes in all papers, where the raw data was compared and contrasted (Fraenkel et al., 2012 ). All three reviewers independently list the words and how the context in which they appeared and then the three reviewers collectively decided for how it should be categorized. Lastly, it is vital to remind that literature review of this article was written after the identification of the themes appeared as a result of our qualitative analyses. Therefore, the authors decided to shape the literature review structure based on the themes.

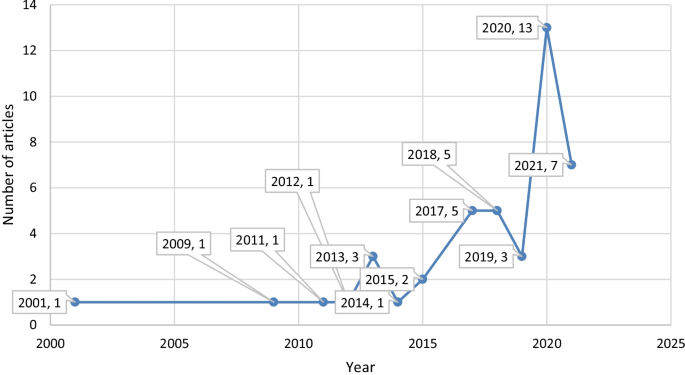

As an answer to the first research question (the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers), Fig. 1 demonstrates the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers. It is seen that there is an increasing trend about the digital literacy papers.

Yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers

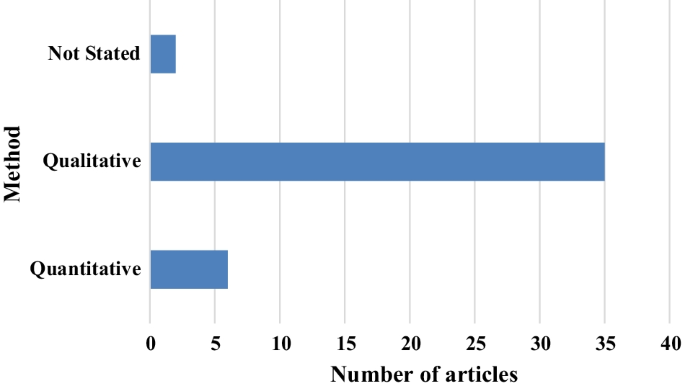

Research question number two (The research methods for digital literacy related papers) concentrates on what research methods are employed for these digital literacy related papers. As Fig. 2 shows, most of the papers were using the qualitative method. Not stated refers to book chapters.

Research methods used in the reviewed articles

When forty-three articles were analysed for the main themes as in research question number three (The main themes in digital literacy related papers), the overall findings were categorized around four major themes: (i) literacies, (ii) competencies, (iii) skills, and (iv) thinking. Under every major theme, the categories were listed and explained as in research question number four (The concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers).

The authors utilized an overt categorization for the depiction of these major themes. For example, when the ‘creativity’ was labelled as a skill, the authors also categorized it under the ‘skills’ theme. Similarly, when ‘creativity’ was mentioned as a competency, the authors listed it under the ‘competencies’ theme. Therefore, it is possible to recognize the same finding under different major themes.

Major theme 1: literacies

Digital literacy being the major concern of this paper was observed to be blatantly mentioned in five papers out forty-three. One of these articles described digital literacy as the human proficiencies to live, learn and work in the current digital society. In addition to these five articles, two additional papers used the same term as ‘critical digital literacy’ by describing it as a person’s or a society’s accessibility and assessment level interaction with digital technologies to utilize and/or create information. Table 2 summarizes the major categories under ‘Literacies’ major theme.

Computer literacy, media literacy and cultural literacy were the second most common literacy (n = 5). One of the article branches computer literacy as tool (detailing with software and hardware uses) and resource (focusing on information processing capacity of a computer) literacies. Cultural literacy was emphasized as a vital element for functioning in an intercultural team on a digital project.

Disciplinary literacy (n = 4) was referring to utilizing different computer programs (n = 2) or technical gadgets (n = 2) with a specific emphasis on required cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills to be able to work in any digital context (n = 3), serving for the using (n = 2), creating and applying (n = 2) digital literacy in real life.

Data literacy, technology literacy and multiliteracy were the third frequent categories (n = 3). The ‘multiliteracy’ was referring to the innate nature of digital technologies, which have been infused into many aspects of human lives.

Last but not least, Internet literacy, mobile literacy, web literacy, new literacy, personal literacy and research literacy were discussed in forty-three article findings. Web literacy was focusing on being able to connect with people on the web (n = 2), discover the web content (especially the navigation on a hyper-textual platform), and learn web related skills through practical web experiences. Personal literacy was highlighting digital identity management. Research literacy was not only concentrating on conducting scientific research ability but also finding available scholarship online.

Twenty-four other categories are unfolded from the results sections of forty-three articles. Table 3 presents the list of these other literacies where the authors sorted the categories in an ascending alphabetical order without any other sorting criterion. Primarily, search, tagging, filtering and attention literacies were mainly underlining their roles in information processing. Furthermore, social-structural literacy was indicated as the recognition of the social circumstances and generation of information. Another information-related literacy was pointed as publishing literacy, which is the ability to disseminate information via different digital channels.

While above listed personal literacy was referring to digital identity management, network literacy was explained as someone’s social networking ability to manage the digital relationship with other people. Additionally, participatory literacy was defined as the necessary abilities to join an online team working on online content production.

Emerging technology literacy was stipulated as an essential ability to recognize and appreciate the most recent and innovative technologies in along with smart choices related to these technologies. Additionally, the critical literacy was added as an ability to make smart judgements on the cost benefit analysis of these recent technologies.

Last of all, basic, intermediate, and advanced digital assessment literacies were specified for educational institutions that are planning to integrate various digital tools to conduct instructional assessments in their bodies.

Major theme 2: competencies

The second major theme was revealed as competencies. The authors directly categorized the findings that are specified with the word of competency. Table 4 summarizes the entire category set for the competencies major theme.

The most common category was the ‘digital competence’ (n = 14) where one of the articles points to that category as ‘generic digital competence’ referring to someone’s creativity for multimedia development (video editing was emphasized). Under this broad category, the following sub-categories were associated:

Problem solving (n = 10)

Safety (n = 7)

Information processing (n = 5)

Content creation (n = 5)

Communication (n = 2)

Digital rights (n = 1)

Digital emotional intelligence (n = 1)

Digital teamwork (n = 1)

Big data utilization (n = 1)

Artificial Intelligence utilization (n = 1)

Virtual leadership (n = 1)

Self-disruption (in along with the pace of digitalization) (n = 1)

Like ‘digital competency’, five additional articles especially coined the term as ‘digital competence as a life skill’. Deeper analysis demonstrated the following points: social competences (n = 4), communication in mother tongue (n = 3) and foreign language (n = 2), entrepreneurship (n = 3), civic competence (n = 2), fundamental science (n = 1), technology (n = 1) and mathematics (n = 1) competences, learning to learn (n = 1) and self-initiative (n = 1).

Moreover, competencies were linked to workplace digital competencies in three articles and highlighted as significant for employability (n = 3) and ‘economic engagement’ (n = 3). Digital competencies were also detailed for leisure (n = 2) and communication (n = 2). Furthermore, two articles pointed digital competencies as an inter-cultural competency and one as a cross-cultural competency. Lastly, the ‘digital nativity’ (n = 1) was clarified as someone’s innate competency of being able to feel contented and satisfied with digital technologies.

Major theme 3: skills

The third major observed theme was ‘skills’, which was dominantly gathered around information literacy skills (n = 19) and information and communication technologies skills (n = 18). Table 5 demonstrates the categories with more than one occurrence.

Table 6 summarizes the sub-categories of the two most frequent categories of ‘skills’ major theme. The information literacy skills noticeably concentrate on the steps of information processing; evaluation (n = 6), utilization (n = 4), finding (n = 3), locating (n = 2) information. Moreover, the importance of trial/error process, being a lifelong learner, feeling a need for information and so forth were evidently listed under this sub-category. On the other hand, ICT skills were grouped around cognitive and affective domains. For instance, while technical skills in general and use of social media, coding, multimedia, chat or emailing in specific were reported in cognitive domain, attitude, intention, and belief towards ICT were mentioned as the elements of affective domain.

Communication skills (n = 9) were multi-dimensional for different societies, cultures, and globalized contexts, requiring linguistic skills. Collaboration skills (n = 9) are also recurrently cited with an explicit emphasis for virtual platforms.

‘Ethics for digital environment’ encapsulated ethical use of information (n = 4) and different technologies (n = 2), knowing digital laws (n = 2) and responsibilities (n = 2) in along with digital rights and obligations (n = 1), having digital awareness (n = 1), following digital etiquettes (n = 1), treating other people with respect (n = 1) including no cyber-bullying (n = 1) and no stealing or damaging other people (n = 1).

‘Digital fluency’ involved digital access (n = 2) by using different software and hardware (n = 2) in online platforms (n = 1) or communication tools (n = 1) or within programming environments (n = 1). Digital fluency also underlined following recent technological advancements (n = 1) and knowledge (n = 1) including digital health and wellness (n = 1) dimension.

‘Social intelligence’ related to understanding digital culture (n = 1), the concept of digital exclusion (n = 1) and digital divide (n = 3). ‘Research skills’ were detailed with searching academic information (n = 3) on databases such as Web of Science and Scopus (n = 2) and their citation, summarization, and quotation (n = 2).

‘Digital teaching’ was described as a skill (n = 2) in Table 4 whereas it was also labelled as a competence (n = 1) as shown in Table 3 . Similarly, while learning to learn (n = 1) was coined under competencies in Table 3 , digital learning (n = 2, Table 4 ) and life-long learning (n = 1, Table 5 ) were stated as learning related skills. Moreover, learning was used with the following three terms: learning readiness (n = 1), self-paced learning (n = 1) and learning flexibility (n = 1).

Table 7 shows other categories listed below the ‘skills’ major theme. The list covers not only the software such as GIS, text mining, mapping, or bibliometric analysis programs but also the conceptual skills such as the fourth industrial revolution and information management.

Major theme 4: thinking

The last identified major theme was the different types of ‘thinking’. As Table 8 shows, ‘critical thinking’ was the most frequent thinking category (n = 4). Except computational thinking, the other categories were not detailed.

Computational thinking (n = 3) was associated with the general logic of how a computer works and sub-categorized into the following steps; construction of the problem (n = 3), abstraction (n = 1), disintegration of the problem (n = 2), data collection, (n = 2), data analysis (n = 2), algorithmic design (n = 2), parallelization & iteration (n = 1), automation (n = 1), generalization (n = 1), and evaluation (n = 2).

A transversal analysis of digital literacy categories reveals the following fields of digital literacy application:

Technological advancement (IT, ICT, Industry 4.0, IoT, text mining, GIS, bibliometric analysis, mapping data, technology, AI, big data)

Networking (Internet, web, connectivity, network, safety)

Information (media, news, communication)

Creative-cultural industries (culture, publishing, film, TV, leisure, content creation)

Academia (research, documentation, library)

Citizenship (participation, society, social intelligence, awareness, politics, rights, legal use, ethics)

Education (life skills, problem solving, teaching, learning, education, lifelong learning)

Professional life (work, teamwork, collaboration, economy, commerce, leadership, decision making)

Personal level (critical thinking, evaluation, analytical thinking, innovative thinking)

This systematic review on digital literacy concentrated on forty-three articles from the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier. The initial results revealed that there is an increasing trend on digital literacy focused academic papers. Research work in digital literacy is critical in a context of disruptive digital business, and more recently, the pandemic-triggered accelerated digitalisation (Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ; Sousa & Rocha 2019 ). Moreover, most of these papers were employing qualitative research methods. The raw data of these articles were analysed qualitatively using systematic literature review to reveal major themes and categories. Four major themes that appeared are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and thinking.

Whereas the mainstream literature describes digital literacy as a set of photo-visual, real-time, information, branching, reproduction and social-emotional thinking (Eshet-Alkalai, 2012 ) or as a set of precise specific operations, i.e., finding, consuming, creating, communicating and sharing digital content (Heitin, 2016 ), this study reveals that digital literacy revolves around and is in connection with the concepts of computer literacy, media literacy, cultural literacy or disciplinary literacy. In other words, the present systematic review indicates that digital literacy is far broader than specific tasks, englobing the entire sphere of computer operation and media use in a cultural context.

The digital competence yardstick, DigComp (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ) suggests that the main digital competencies cover information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving. Similarly, the findings of this research place digital competencies in relation to problem solving, safety, information processing, content creation and communication. Therefore, the findings of the systematic literature review are, to a large extent, in line with the existing framework used in the European Union.

The investigation of the main keywords associated with digital skills has revealed that information literacy, ICT, communication, collaboration, digital content creation, research and decision-making skill are the most representative. In a structured way, the existing literature groups these skills in technological, cognitive, and social (Ng, 2012 ) or, more extensively, into operational, formal, information Internet, strategic, communication and content creation (van Dijk & van Deursen, 2014 ). In time, the literature has become richer in frameworks, and prolific authors have improved their results. As such, more recent research (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) use the following categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Whereas digital thinking was observed to be mostly related with critical thinking and computational thinking, DigComp connects it with critical thinking, creativity, and innovation, on the one hand, and researchers highlight fake news, misinformation, cybersecurity, and echo chambers as exponents of digital thinking, on the other hand (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

This systematic review research study looks ahead to offer an initial step and guideline for the development of a more contemporary digital literacy framework including digital literacy major themes and factors. The researchers provide the following recommendations for both researchers and practitioners.

Recommendations for prospective research

By considering the major qualitative research trend, it seems apparent that more quantitative research-oriented studies are needed. Although it requires more effort and time, mixed method studies will help understand digital literacy holistically.

As digital literacy is an umbrella term for many different technologies, specific case studies need be designed, such as digital literacy for artificial intelligence or digital literacy for drones’ usage.

Digital literacy affects different areas of human lives, such as education, business, health, governance, and so forth. Therefore, different case studies could be carried out for each of these unique dimensions of our lives. For instance, it is worth investigating the role of digital literacy on lifelong learning in particular, and on education in general, as well as the digital upskilling effects on the labour market flexibility.

Further experimental studies on digital literacy are necessary to realize how certain variables (for instance, age, gender, socioeconomic status, cognitive abilities, etc.) affect this concept overtly or covertly. Moreover, the digital divide issue needs to be analysed through the lens of its main determinants.

New bibliometric analysis method can be implemented on digital literacy documents to reveal more information on how these works are related or centred on what major topic. This visual approach will assist to realize the big picture within the digital literacy framework.

Recommendations for practitioners

The digital literacy stakeholders, policymakers in education and managers in private organizations, need to be aware that there are many dimensions and variables regarding the implementation of digital literacy. In that case, stakeholders must comprehend their beneficiaries or the participants more deeply to increase the effect of digital literacy related activities. For example, critical thinking and problem-solving skills and abilities are mentioned to affect digital literacy. Hence, stakeholders have to initially understand whether the participants have enough entry level critical thinking and problem solving.

Development of digital literacy for different groups of people requires more energy, since each group might require a different set of skills, abilities, or competencies. Hence, different subject matter experts, such as technologists, instructional designers, content experts, should join the team.

It is indispensably vital to develop different digital frameworks for different technologies (basic or advanced) or different contexts (different levels of schooling or various industries).

These frameworks should be updated regularly as digital fields are evolving rapidly. Every year, committees should gather around to understand new technological trends and decide whether they should address the changes into their frameworks.

Understanding digital literacy in a thorough manner can enable decision makers to correctly implement and apply policies addressing the digital divide that is reflected onto various aspects of life, e.g., health, employment, education, especially in turbulent times such as the COVID-19 pandemic is.

Lastly, it is also essential to state the study limitations. This study is limited to the analysis of a certain number of papers, obtained from using the selected keywords and databases. Therefore, an extension can be made by adding other keywords and searching other databases.

Availability of data and materials

The authors present the articles used for the study in “ Appendix A ”.

Baber, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., Lee, Y. T., & Tinmaz, H. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of digital literacy research and emerging themes pre-during COVID-19 pandemic. Information and Learning Sciences . https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-10-2021-0090 .

Article Google Scholar

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111 , 10642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Avdiel, O. (2020). How does the pedagogical design of a technology-enhanced collaborative academic course promote digital literacies, self-regulation, and perceived learning of students? The Internet and Higher Education, 45 , 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100722

Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with eight proficiency levels and examples of use (No. JRC106281). Joint Research Centre, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC106281

Eshet, Y. (2004). Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia , 13 (1), 93–106, https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/4793/

Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 9 (2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.28945/1621

Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. JCR IPTS, Sevilla. https://ifap.ru/library/book522.pdf

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education (8th ed.). Mc Graw Hill.

Google Scholar

Heitin, L. (2016). What is digital literacy? Education Week, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/what-is-digital-literacy/2016/11

Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2013). Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. European Journal of Communication, 28 (6), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113499113

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference ? . Radiologic Technology, 85 (2), 219–222.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59 (3), 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016

Ozkan-Ozen, Y. D., & Kazancoglu, Y. (2021). Analysing workforce development challenges in the Industry 4.0. International Journal of Manpower . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2021-0167

Puig, B., Blanco-Anaya, P., & Perez-Maceira, J. J. (2021). “Fake News” or Real Science? Critical thinking to assess information on COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 6 , 646909. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.646909

Robinson, L., Cotten, S. R., Ono, H., Quan-Haase, A., Mesch, G., Chen, W., Schulz, J., Hale, T. M., & Stern, M. J. (2015). Digital inequalities and why they matter. Information, Communication & Society, 18 (5), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1012532

Robinson, P., & Lowe, J. (2015). Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39 (2), 103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393

Sousa, M. J., & Rocha, A. (2019). Skills for disruptive digital business. Journal of Business Research, 94 , 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.051

Sulzer, A. (2018). (Re)conceptualizing digital literacies before and after the election of Trump. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 17 (2), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-06-2017-0098

Tinmaz, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A snapshot of digital literacy. Library Hi Tech News , (ahead-of-print).

Uman, L. S. (2011). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20 (1), 57–59.

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2015). Development and validation of the Internet Skills Scale (ISS). Information, Communication & Society, 19 (6), 804–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1078834

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2009). Using the internet: Skills related problems in users’ online behaviour. Interacting with Computers, 21 , 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2009.06.005

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010a). Measuring internet skills. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 26 (10), 891–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2010.496338

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010b). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 13 (6), 893–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810386774

van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & Van Deursen, A. J. A. M. (2014). Digital skills, unlocking the information society . Palgrave MacMillan.

van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & de Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computer in Human Behavior, 72 , 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Download references

This research is funded by Woosong University Academic Research in 2022.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

AI & Big Data Department, Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Hasan Tinmaz

Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Yoo-Taek Lee

Department of Economics and Economic Policies, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

Mina Fanea-Ivanovici

Abu Dhabi School of Management, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Hasnan Baber

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors worked together on the manuscript equally. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hasnan Baber .

Ethics declarations

Competing of interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tinmaz, H., Lee, YT., Fanea-Ivanovici, M. et al. A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learn. Environ. 9 , 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Download citation

Received : 23 February 2022

Accepted : 01 June 2022

Published : 08 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital literacy

- Systematic review

- Qualitative research

November 1, 2013

12 min read

The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: Why Paper Still Beats Screens

E-readers and tablets are becoming more popular as such technologies improve, but reading on paper still has its advantages

By Ferris Jabr

One of the most provocative viral YouTube videos in the past two years begins mundanely enough: a one-year-old girl plays with an iPad, sweeping her fingers across its touch screen and shuffling groups of icons. In following scenes, she appears to pinch, swipe and prod the pages of paper magazines as though they, too, are screens. Melodramatically, the video replays these gestures in close-up.

For the girl's father, the video— A Magazine Is an iPad That Does Not Work —is evidence of a generational transition. In an accompanying description, he writes, “Magazines are now useless and impossible to understand, for digital natives”—that is, for people who have been interacting with digital technologies from a very early age, surrounded not only by paper books and magazines but also by smartphones, Kindles and iPads.

Whether or not his daughter truly expected the magazines to behave like an iPad, the video brings into focus a question that is relevant to far more than the youngest among us: How exactly does the technology we use to read change the way we read?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Since at least the 1980s researchers in psychology, computer engineering, and library and information science have published more than 100 studies exploring differences in how people read on paper and on screens. Before 1992 most experiments concluded that people read stories and articles on screens more slowly and remember less about them. As the resolution of screens on all kinds of devices sharpened, however, a more mixed set of findings began to emerge. Recent surveys suggest that although most people still prefer paper—especially when they need to concentrate for a long time—attitudes are changing as tablets and e-reading technology improve and as reading digital texts for facts and fun becomes more common. In the U.S., e-books currently make up more than 20 percent of all books sold to the general public.

Despite all the increasingly user-friendly and popular technology, most studies published since the early 1990s confirm earlier conclusions: paper still has advantages over screens as a reading medium. Together laboratory experiments, polls and consumer reports indicate that digital devices prevent people from efficiently navigating long texts, which may subtly inhibit reading comprehension. Compared with paper, screens may also drain more of our mental resources while we are reading and make it a little harder to remember what we read when we are done. Whether they realize it or not, people often approach computers and tablets with a state of mind less conducive to learning than the one they bring to paper. And e-readers fail to re-create certain tactile experiences of reading on paper, the absence of which some find unsettling.

“There is physicality in reading,” says cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf of Tufts University, “maybe even more than we want to think about as we lurch into digital reading—as we move forward perhaps with too little reflection. I would like to preserve the absolute best of older forms but know when to use the new.”

Textual Landscapes Understanding how reading on paper differs from reading on screens requires some explanation of how the human brain interprets written language. Although letters and words are symbols representing sounds and ideas, the brain also regards them as physical objects. As Wolf explains in her 2007 book Proust and the Squid , we are not born with brain circuits dedicated to reading, because we did not invent writing until relatively recently in our evolutionary history, around the fourth millennium b.c. So in childhood, the brain improvises a brand-new circuit for reading by weaving together various ribbons of neural tissue devoted to other abilities, such as speaking, motor coordination and vision.

Some of these repurposed brain regions specialize in object recognition: they help us instantly distinguish an apple from an orange, for example, based on their distinct features, yet classify both as fruit. Similarly, when we learn to read and write, we begin to recognize letters by their particular arrangements of lines, curves and hollow spaces—a tactile learning process that requires both our eyes and hands. In recent research by Karin James of Indiana University Bloomington, the reading circuits of five-year-old children crackled with activity when they practiced writing letters by hand but not when they typed letters on a keyboard. And when people read cursive writing or intricate characters such as Japanese kanji , the brain literally goes through the motions of writing, even if the hands are empty.

Beyond treating individual letters as physical objects, the human brain may also perceive a text in its entirety as a kind of physical landscape. When we read, we construct a mental representation of the text. The exact nature of such representations remains unclear, but some researchers think they are similar to the mental maps we create of terrain—such as mountains and trails—and of indoor physical spaces, such as apartments and offices. Both anecdotally and in published studies, people report that when trying to locate a particular passage in a book, they often remember where in the text it appeared. Much as we might recall that we passed the red farmhouse near the start of a hiking trail before we started climbing uphill through the forest, we remember that we read about Mr. Darcy rebuffing Elizabeth Bennett at a dance on the bottom left corner of the left-hand page in one of the earlier chapters of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice .

In most cases, paper books have more obvious topography than on-screen text. An open paper book presents a reader with two clearly defined domains—the left- and right-hand pages—and a total of eight corners with which to orient oneself. You can focus on a single page of a paper book without losing awareness of the whole text. You can even feel the thickness of the pages you have read in one hand and the pages you have yet to read in the other. Turning the pages of a paper book is like leaving one footprint after another on a trail—there is a rhythm to it and a visible record of how far one has traveled. All these features not only make the text in a paper book easily navigable, they also make it easier to form a coherent mental map of that text.

In contrast, most digital devices interfere with intuitive navigation of a text and inhibit people from mapping the journey in their mind. A reader of digital text might scroll through a seamless stream of words, tap forward one page at a time or use the search function to immediately locate a particular phrase—but it is difficult to see any one passage in the context of the entire text. As an analogy, imagine if Google Maps allowed people to navigate street by individual street, as well as to teleport to any specific address, but prevented them from zooming out to see a neighborhood, state or country. Likewise, glancing at a progress bar gives a far more vague sense of place than feeling the weight of read and unread pages. And although e-readers and tablets replicate pagination, the displayed pages are ephemeral. Once read, those pages vanish. Instead of hiking the trail yourself, you watch the trees, rocks and moss pass by in flashes, with no tangible trace of what came before and no easy way to see what lies ahead.

“The implicit feel of where you are in a physical book turns out to be more important than we realized,” says Abigail J. Sellen of Microsoft Research Cambridge in England, who co-authored the 2001 book The Myth of the Paperless Office . “Only when you get an e-book do you start to miss it. I don't think e-book manufacturers have thought enough about how you might visualize where you are in a book.”

Exhaustive Reading At least a few studies suggest that screens sometimes impair comprehension precisely because they distort people's sense of place in a text. In a January 2013 study by Anne Mangen of the University of Stavanger in Norway and her colleagues, 72 10th grade students studied one narrative and one expository text. Half the students read on paper, and half read PDF files on computers. Afterward, students completed reading comprehension tests, during which they had access to the texts. Students who read the texts on computers performed a little worse, most likely because they had to scroll or click through the PDFs one section at a time, whereas students reading on paper held the entire texts in their hands and quickly switched between different pages. “The ease with which you can find out the beginning, end, and everything in between and the constant connection to your path, your progress in the text, might be some way of making it less taxing cognitively,” Mangen says. “You have more free capacity for comprehension.”

Other researchers agree that screen-based reading can dull comprehension because it is more mentally taxing and even physically tiring than reading on paper. E-ink reflects ambient light just like the ink on a paper book, but computer screens, smartphones and tablets shine light directly on people's faces. Today's LCDs are certainly gentler on eyes than their predecessor, cathode-ray tube (CRT) screens, but prolonged reading on glossy, self-illuminated screens can cause eyestrain, headaches and blurred vision. In an experiment by Erik Wästlund, then at Karlstad University in Sweden, people who took a reading comprehension test on a computer scored lower and reported higher levels of stress and tiredness than people who completed it on paper.

In a related set of Wästlund's experiments, 82 volunteers completed the same reading comprehension test on computers, either as a paginated document or as a continuous piece of text. Afterward, researchers assessed the students' attention and working memory—a collection of mental talents allowing people to temporarily store and manipulate information in their mind. Volunteers had to quickly close a series of pop-up windows, for example, or remember digits that flashed on a screen. Like many cognitive abilities, working memory is a finite resource that diminishes with exertion.

Although people in both groups performed equally well, those who had to scroll through the unbroken text did worse on the attention and working memory tests. Wästlund thinks that scrolling—which requires readers to consciously focus on both the text and how they are moving it—drains more mental resources than turning or clicking a page, which are simpler and more automatic gestures. The more attention is diverted to moving through a text, the less is available for understanding it. A 2004 study conducted at the University of Central Florida reached similar conclusions.

An emerging collection of studies emphasizes that in addition to screens possibly leeching more attention than paper, people do not always bring as much mental effort to screens in the first place. Based on a detailed 2005 survey of 113 people in northern California, Ziming Liu of San Jose State University concluded that those reading on screens take a lot of shortcuts—they spend more time browsing, scanning and hunting for keywords compared with people reading on paper and are more likely to read a document once and only once.

When reading on screens, individuals seem less inclined to engage in what psychologists call metacognitive learning regulation—setting specific goals, rereading difficult sections and checking how much one has understood along the way. In a 2011 experiment at the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, college students took multiple-choice exams about expository texts either on computers or on paper. Researchers limited half the volunteers to a meager seven minutes of study time; the other half could review the text for as long as they liked. When under pressure to read quickly, students using computers and paper performed equally well. When managing their own study time, however, volunteers using paper scored about 10 percentage points higher. Presumably, students using paper approached the exam with a more studious attitude than their screen-reading peers and more effectively directed their attention and working memory.

Even when studies find few differences in reading comprehension between screens and paper, screen readers may not remember a text as thoroughly in the long run. In a 2003 study Kate Garland, then at the University of Leicester in England, and her team asked 50 British college students to read documents from an introductory economics course either on a computer monitor or in a spiral-bound booklet. After 20 minutes of reading, Garland and her colleagues quizzed the students. Participants scored equally well regardless of the medium but differed in how they remembered the information.

Psychologists distinguish between remembering something—a relatively weak form of memory in which someone recalls a piece of information, along with contextual details, such as where and when one learned it—and knowing something: a stronger form of memory defined as certainty that something is true. While taking the quiz, Garland's volunteers marked both their answer and whether they “remembered” or “knew” the answer. Students who had read study material on a screen relied much more on remembering than on knowing, whereas students who read on paper depended equally on the two forms of memory. Garland and her colleagues think that students who read on paper learned the study material more thoroughly more quickly; they did not have to spend a lot of time searching their mind for information from the text—they often just knew the answers.

Perhaps any discrepancies in reading comprehension between paper and screens will shrink as people's attitudes continue to change. Maybe the star of A Magazine Is an iPad That Does Not Work will grow up without the subtle bias against screens that seems to lurk among older generations. The latest research suggests, however, that substituting screens for paper at an early age has disadvantages that we should not write off so easily. A 2012 study at the Joan Ganz Cooney Center in New York City recruited 32 pairs of parents and three- to six-year-old children. Kids remembered more details from stories they read on paper than ones they read in e-books enhanced with interactive animations, videos and games. These bells and whistles deflected attention away from the narrative toward the device itself. In a follow-up survey of 1,226 parents, the majority reported that they and their children prefer print books over e-books when reading together.

Nearly identical results followed two studies, described this past September in Mind, Brain, and Education , by Julia Parrish-Morris, now at the University of Pennsylvania, and her colleagues. When reading paper books to their three- and five-year-old children, parents helpfully related the story to their child's life. But when reading a then popular electric console book with sound effects, parents frequently had to interrupt their usual “dialogic reading” to stop the child from fiddling with buttons and losing track of the narrative. Such distractions ultimately prevented the three-year-olds from understanding even the gist of the stories, but all the children followed the stories in paper books just fine.

Such preliminary research on early readers underscores a quality of paper that may be its greatest strength as a reading medium: its modesty. Admittedly, digital texts offer clear advantages in many different situations. When one is researching under deadline, the convenience of quickly accessing hundreds of keyword-searchable online documents vastly outweighs the benefits in comprehension and retention that come with dutifully locating and rifling through paper books one at a time in a library. And for people with poor vision, adjustable font size and the sharp contrast of an LCD screen are godsends. Yet paper, unlike screens, rarely calls attention to itself or shifts focus away from the text. Because of its simplicity, paper is “a still point, an anchor for the consciousness,” as William Powers writes in his 2006 essay “Hamlet's Blackberry: Why Paper Is Eternal.” People consistently report that when they really want to focus on a text, they read it on paper. In a 2011 survey of graduate students at National Taiwan University, the majority reported browsing a few paragraphs of an item online before printing out the whole text for more in-depth reading. And in a 2003 survey at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, nearly 80 percent of 687 students preferred to read text on paper rather than on a screen to “understand it with clarity.”