- All Journals

- Real Estate / Property

Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning

Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning is the leading professional journal publishing peer-reviewed articles and case studies written by and for business continuity and emergency managers.

Each quarterly 100-page issue combines provocative thought-leadership pieces – which expand what can be achieved with business continuity and emergency management – with detailed, actionable advice and ‘lessons learned’, showing how programmes have been specified, designed, implemented, tested and updated, as well as how interruptions, emergencies and exercises have been managed in practice. The journal focuses on key strategic and business issues – not technical minutiae – with no advertorial or advertising.

Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning is listed, indexed and abstracted in PubMed, Scopus and Cabells' Directories of Publishing Opportunities.

Each issue analyses the latest practice, innovative techniques and leading-edge thinking in:

- Identifying and preparing for new areas of risk

- Business impact analysis

- Defining and protecting mission critical operations

- Crisis communications and decision making

- Reputation risk management

- Natural and environmental risks

- Supply chain risk management

- Pandemics and other public health threats

- Making the business case for plan investments

- Case studies of how plans respond in practice to interruptions and emergencies

- Public-private partnerships and intra-agency planning

- Aligning plans with organisational goals

- Drafting and implementing plans

- Training and awareness programmes

- Plan tests, exercises and updates

- Security and public safety

- Telecoms, records and data infrastructure resilience

Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning publishes in-depth, end-user focused articles and real world case studies written by experienced business continuity and emergency managers who provide insight into current and best practice at blue chip corporations, central and local government and humanitarian agencies. Authors documenting their practical experience, problems encountered, solutions adopted and 'lessons learned' in previous issues have included:

Business continuity managers from: ABN AMRO; Air New Zealand; Amway; Associated Press; BAE Systems; Bank of England; Blue Cross and Blue Shield; BP; Canary Wharf Group; CenturyLink; Cisco; Citigroup; City University, London; Credit Suisse; Cushman & Wakefield; Deutsche Bank; DHL; DTE Energy; eBay; Emirates Group; Ernst & Young; FedEx; Gap; Greater Toronto Airports Authority; Hewlett-Packard; Intel; Johns Hopkins University; Kaiser Permanente; KPMG; Lockheed Martin; Merck & Co; Pfizer; PwC; Sun Microsystems; Target; Union Bank; US Department of State; US Securities & Exchange Commission; Verizon; Vodafone; Walgreen Co; Warner Bros; Wells Fargo; Zurich Financial Services.

Emergency managers from : American Red Cross; Boston Emergency Medical Services; Calgary Emergency Management Agency; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ChicagoFIRST; East Central Florida Planning Council; FEMA; Government of Western Australia; Health Protection Agency; Los Angeles County EMS Agency; Merseyside Police; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation; NHS London; Orlando International Airport; Port of Seattle; Santa Rosa County Division of Emergency Management, Florida; Scottish Government; Southern Methodist University; Surrey County Council; UCLA Health System; US Department of Homeland Security; UNISDR; US Army; World Health Organization.

Essential source material for Departmental Heads, Managing Directors, SVPs, EVPs, VPs, Directors and Senior Managers of:

- Business continuity

- Emergency management

- Risk management

- Emergency planning

- Business resilience

- Disaster recovery

- Crisis management

- Emergency response

- Public health

- Environment, health and safety

- Homeland security

- Financial stability and market infrastructure

- IT and information security; as well as

- CEOs and other C-Suite executives

- Service providers, auditors and consultants

“I find the content of Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning to be up to date, easy to follow, and applicable to the professional in the field, the student in the class, and the academic. This journal offers a mix of articles from many disciplines in a manner that allows the professional to utilise the data immediately. I have personally used material from this journal on multiple occasions, both in my academic and professional endeavours.”

" Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning fills a significant dearth in the peer-reviewed, international perspective emergency management literature."

"In a world where business continuity is now an integral part of everyday life, the Journal provides a holistic look across all industries at how others manage risk. The insights provided are thought provoking and very practical. During its years of publication, the Journal has grown from strength to strength in both its readership and quality and depth of the challenging articles."

"Written by and for the professional, it provides me with the kind of practical, real-use cases I can apply in my job."

Contact Information

Henry Stewart Publications LLP

Registered office: Ruskin House, 40/41 Museum Street

London, WC1A 1LT, UK

Tel: +44 (0)20 7092 3465

Email: [email protected]

Registered in England, Incorporation No. OC 317997

Footer Menu

- © 2016 Henry Stewart Publications

- Terms & Conditions

- Publication Ethics

- Accessibility

- Copyright and Permissions

- Sustainability and Environment

Business continuity in the COVID-19 emergency: A framework of actions undertaken by world-leading companies

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Salento, Campus Ecotekne, Via Monteroni s.n., 73100 Lecce (LE), Italy.

- 2 Centre for Collaborative Research (CCR), Turku School of Economics, University of Turku, Rehtorinpellonkatu 3, FI-20500 Turku, Finland.

- PMID: 33558777

- PMCID: PMC7859707

- DOI: 10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.020

The COVID-19 emergency has urged companies to operate in new ways to face supply chain interruptions, shifts in customer demand, and risks to workforce health. The organizational ability to respond to critical contingencies is crucial for business leaders in the perspective of continuing business. In our research, we investigate the actions undertaken by 50 world-leading corporations to respond to the pandemic. Applying content analysis to web pages and social network posts, we extract 77 actions related to 13 sub-areas and integrate these into a five-level framework that encompasses operations, customer, workforce, leadership, and community-related responses. We also describe six illustrative company examples of how the emergency can generate opportunities for creating new value. The study advances the scholarly discussion on the impact of emergencies on business continuity and can help leaders define response strategies and actions in the current challenge.

Keywords: Business continuity; COVID-19; Framework; Operations; Responses; Value creation; Workforce.

© 2021 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Advertisement

Business continuity through customer engagement in sustainable supply chain management: outlining the enablers to manage disruption

- Research Article

- Published: 08 October 2021

- Volume 29 , pages 14999–15017, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Amrinder Kaur 1 ,

- Ashwani Kumar 2 &

- Sunil Luthra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7571-1331 3

4689 Accesses

9 Citations

Explore all metrics

Business continuity in disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic involves sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) with limited resources and risks for the well-being and prosperity of stakeholders and customers involved with limited environmental effects. The purpose of the paper is to outline enablers in customer engagement that supports SSCM in times of disruption like the COVID-19 pandemic. This research uses an extensive literature review followed by academic and industry practitioners’ opinions to identify customer engagement enablers in SSCM for business continuity. Hybrid stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA) and rough set numbers rank customer engagement enablers that support SSCM in disruption. The research builds on stakeholder theory and the sustainability framework for economic performance through non-economic aspects. The research concludes that the focus on agility for target customers through collaboration and information sharing in SSCM will support business continuity. It shall support decision-making in the supply chain in uncertainties. Engagement with stakeholders leads to focused execution in response to customer demand through faster communication and crucial information sharing, thus eliminating bottlenecks for business continuity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Performance Monitoring: An Agile New Tool for Facilitating Sustainability in Value Chains

Key Success Factors for Supply Chain Sustainability in COVID-19 Pandemic: An ISM Approach

Big data analytics in mitigating challenges of sustainable manufacturing supply chain

Rohit Raj, Vimal Kumar & Pratima Verma

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a disruption that witnessed massive health scare, economic recession with plunging demand, business discontinuity and in general, slowing down of economic activities (Carlsson-Szlezak et al. 2020 ; Jayaram et al. 2020 ). Business continuity (Cerullo and Cerullo 2004 ; Herbane et al. 2004 ) has supply chain management (SCM) as its intrinsic part (Schätter et al. 2019 ; Shashi et al. 2019 ) as, during disruptions, the movement of resources and value additions through goods/services from both the demand and supply side gets affected. SCM is an efficient movement of resources and information and assesses demand (Skjoett-Larsen et al. 2003 ; Sharma et al. 2020 ). However, the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the vulnerability of global supply chains (Kumar 2020 ), with lesser margins to absorb errors and a faltering of economies worldwide along with closure of businesses (Building a More Resilient ICT Supply Chain: Lessons Learned during the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 ; Magdin 2021 ).

For a long time, organisations’ focus had been on cost and inventory optimisation, supplier strategies and lean inventory, just in time process, focusing on critical node suppliers only (Seuring and Müller 2008b ; Butner 2010 ; Kilpatrick and Barter 2020 ). Disruption by the pandemic demonstrated the vulnerabilities of SC and businesses (Shammi et al. 2020 ; Silverthorne 2020 ). Survival and rebounding had been easy for organisations with an integrated approach with customers through structures, technologies and communities and shared identity (Papageorgiou 2009 ; Abdelnour et al. 2020 ). The organisations that sustained themselves well in the pandemic are the ones that created a sustainable and resilient supply chain. For instance, the resilient SCM supported business continuity in global companies like Nestle, which reportedly saw growth during the pandemic (Kumar 2020 ) like other digital and healthcare businesses (Abdelnour et al. 2020 ). However, the pandemic affected growth and economic activity especially in emerging economies like India, Bangladesh and many countries leading to high unemployment, lower gross domestic product (GDP) and closure of businesses (Shammi et al. 2020 ).

Business continuity in extreme disruption like pandemics and climate change is significant as 90% of businesses globally are small and medium enterprises (SME). The World Bank reports that formal SME contributes around 40% of GDP in emerging economies (Small and Medium Enterprises and Finance 2020 ) while the rest is in the informal economy. Emerging economies are differentiated from the matured markets by their per capita income, limited infrastructure and growth (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ). Businesses in emerging economies have lesser access to finance, technology and knowledge to deal with business disruptions than developed economies (Szekely and Kemanian 2016 ; Sneader and Singhal 2021 ). The supply chain is now global (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) while integrating the local vendors, suppliers and other customers. Business continuity depends on effective collaboration with different customers, including vendors and suppliers, to cater to the market’s needs and demand (Chopra et al. 2011 ; Alicke and Strigek 2020 ). Emerging economies are an essential link of the global supply chains as manufacturing, production and a host of development activities are based in these economies (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ).

SSCM emphasises the triple bottom line (Elkington 1999 ) with people, profit and the planet. People involving local communities, internal and external customers (Kaur and Bhardwaj 2019 ; Kiron et al. 2015 ) and stakeholders’ collaboration are crucial to managing organisational activities (Seuring and Muller 2008a ; Silvestre et al. 2018 ). The people or social aspect of SCM is vital due to the complexity of supply chains (Mani et al. 2016 ; Govindan et al. 2021 ), and value creation involves collaboration for relational terms between different entities of available resources and capabilities (Caldwell et al. 2017 ). The relation coordination supports performance enhancement with different entities (Roehrich et al. 2019 ), and is affected by a lack of goal alignment, effective governance mechanism, unethical practices and knowledge asymmetry between the different parties (Kalra et al. 2021 ).

Customer engagement builds a shared identity (Grewal et al. 2017 ) with internal and external customers to achieve organisation’s economic performance (Al-Dmour et al. 2019 ) and also respond effectively to global and potential risk (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ). Carter and Rogers’s ( 2008 ) conceptual framework on sustainability involving the triple bottom line of economic, environmental and social aspects concludes strategic and effective coordination for competitiveness, and resilience (Seuring and Muller 2008b ) of focal organisation and supply chain.

Disruptions are long-term and short-term disturbances (Nikolopoulos et al. 2020 ), affecting organisations’ day-to-day activities and ability to achieve short-term and long-term goals. It can vary in nature, type and frequency but affect SC operations. For instance, service failure is a short-term disruption (Zheng et al. 2008 ), and disasters like flood, fire at a manufacturing facility and pandemic can have effect on more than one entity in a supply chain (Azadegan et al. 2020 ) causing a delay in deliveries, affecting revenues, sales and workforce utilisation with ultimate effect on an organisation’s position in the market (Ivanov and Dolgui 2020 ). SSCM is also the management of high-impact, high-risk, low-frequency disruptions like the one caused in the COVID-19 pandemic (Li and Zobel 2020 ). The COVID-19 pandemic (Nikolopoulos et al. 2020 ) that affected businesses worldwide need effective integration and coordination for business continuity through identification of critical enablers by decision-makers(Alicke and Strigek 2020 ; Degnarain 2020 ; Evans et al. 2017 ). Stakeholders (Herbane et al. 2004 ; McKnight and Linnenluecke 2016 ) play the essential role in SSCM in times of threats and significant disruptions. Thus, safety, scarcity of resources and decisions related to stakeholders need to be considered (Carter and Rogers 2008 ). Engagement with customers, closing the supply chain loops (Kazancoglu et al. 2020 ) and supporting greater customer satisfaction/loyalty, is essential for business continuity (Kumar et al. 2013 ).

Researchers assert that many approaches support and are put into practice to contain risk and maintain business continuity in SCM, like reducing the complexity of the supply chain’s nodes and network, relying on the stored inventory and building additional capacities (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ). However, stakeholders’ strategic priorities act as barriers to resilience and business continuity (Ali et al. 2017 ). Also, emerging economies’ integration and coordination are affected by a lack of awareness, knowledge and finance (Bag et al. 2018 ).

The uncertainty of COVID-19 increased the instances of hoarding, storage (Jabbour and Jabbour 2020 ) with customers and muted demand with disintegrated supply chains. Identification of the enablers that support the ability of organisations to respond by more integration (Wankmüller and Reiner 2019 ) will lead to efficient management of resources and decision-making vital for business continuity. This identification of enablers is vital for emerging economies that deal with climate changes like earthquakes and floods, and lack knowledge and financial prowess to draft a response to ensure economic performance (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ).

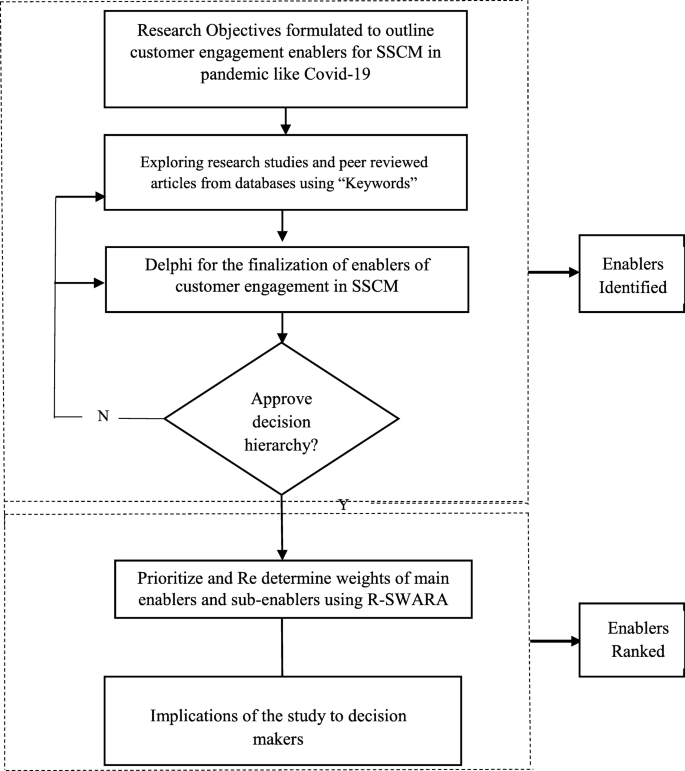

Identification for prioritisation of customer engagement enablers in SSCM for business continuity leads to research questions which further became the objectives explored in the research. The first research question had been to identify if economic performance can be maintained through collaboration and integration among different customers or entities in the supply chain in times of supply chain disruption . And what are the enablers for engagement that can support in times of disruption for business continuity. Mani et al. ( 2016 ) assert the stakeholder and resource-based theory in social sustainability to support decision-makers utilising their resources and capabilities along with other customers and partners to create a sustainable advantage. Thus, the other research question was if these enablers can be ranked and prioritised for effective utilisation of resources and value creation to manage disruption in the supply chain. The conceptual sustainability framework by Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ) was referred which focused on the importance of achieving economic performance by integrating non-economic factors. Hence, the research objectives for identifying and prioritising the customer engagement enablers for managerial implications to support decisions and practices for business continuity are as below:

RO1: To identify the enablers of customer engagement in SSCM to manage disruption for business continuity.

RO2: To rank and prioritise the enablers of customer engagement in SSCM.

RO3: To enhance the value utilisation of resources more responsibly as we move forward, focusing on customer engagement in a sustainable supply chain.

An extensive literature review was carried out as per the research objectives, followed by academic and industry practitioners’ opinions to identify customer engagement enablers in SSCM for business continuity. Hybrid stepwise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA) and rough set numbers rank customer engagement enablers supporting SSCM in disruption. The research is significant as it builds on the earlier approaches of stakeholder theory to support business continuity (Herbane et al. 2004 ; Hofmann et al. 2013 ; McKnight and Linnenluecke 2016 ) through integration between different entities. Theoretically, the research builds on Cater and Rogers’s ( 2008 ) framework on sustainability, which includes resource dependence theory emphasising economic performance through non-economic factors. Enhanced sustainability mitigates the effects of disruption in SCM (Sajjad et al. 2015 ; Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ). It includes disruption for production and supply sides and is accomplished by improving the deliverables with engaged stakeholders, including customers. Demand visibility and clarity on customer preferences through effective collaboration, information sharing and seamless integration with various stakeholders enhance economic performance with the inclusion of environmental and social factors of the supply chain (Thron et al. 2006 ; Hofmann et al. 2013 ; Gouda and Saranga 2018 ), and are essential for emerging economies that are a part of global supply chains. The manuscript identifies enablers in SSCM for business continuity in global supply chains with an emerging economy perspective.

The paper is divided into six sections. A review of the literature for customer engagement and SSCM is in the “Literature review” section. The “Research methodology” section defines the research methodology, followed by the “Data analysis and results” section and the “Discussions and implications” section with discussions and implications. The “Conclusion and limitations of research” section is the conclusions with limitations of research.

Literature review

For the study to outline customer engagement enablers in SSCM for business continuity, a systematic literature review process was undertaken by adopting from the work of Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ), Fischl et al. ( 2014 ), Seuring and Muller ( 2008a ), Vivek et al. ( 2014 ) and Zhang et al. ( 2020 ). Research articles and studies from various databases like Web of Science, Science-direct, EBSCO, SCOPUS, ProQuest, Emerald and Google were explored, and final research articles were selected based on the following criteria.

As sustainability started gaining more prominence, the post-Brundtland Commission report (WCED 1987 ) on the importance of sustainability and Elkington’s ( 1999 ) definition of triple bottom line involving people, profit and the planet. The time horizon for the research work is from 1990 to 2021.

Identification of relevant research articles was made using the keywords like “Sustainable Supply Chain Management”, “Strategic Sourcing”, “Customer Engagement in Sustainable Supply Chain Management”, “Supplier relationship management”, “Business continuity and sustainability”, “Business Continuity and Sustainability”, “Sustainable business practices”, “Disruption management in the supply chain” and “Business continuity and stakeholder theory in SSCM”.

For further inclusion and exclusion of research studies, Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ), Seuring and Muller ( 2008a ), Vivek et al. ( 2014 ), Shashi et al. ( 2019 ) and Zhang et al. ( 2020 ) were referred. The selection process of articles was performed in multiple folds. First, we included articles written in English language and published in peer-reviewed journals. Likewise, we exclude the obfuscated literature such as magazine, conference proceedings, doctoral thesis, white papers, workshop summary, poster presentations and news blogs to increase the reliability of the study. After screening process, 130 peer-reviewed articles from more than 40 journals considered for the review process. In the SLR process, a sorting process was performed in which title and abstract reviews were analysed to select research papers that suggest clear management focus pertaining to customer engagement in supply chain, business continuity and sustainable business. To avoid any human biasness and vagueness in article selection, we thoroughly read the full article before leading to final decision. Hence, rigorous search process was performed, resulting in a final set of 72 research articles to be considered for the study.

This research also references studies made by Mc-Kinsey and the company for more relevance to current business practices in the pandemic.

Subsequent sections summarise the literature review followed with research gaps for outlining the enablers of customer engagement for sustainable supply chain management in disruptions like COVID-19.

Engagement for business continuity

The literature in SSCM earlier focused on environmental practices, including green SCM and procurement practices involving recycling, waste reduction, developing environmentally safe products, environmental impact assessment of various partners, measurement and accounting of sustainability (Amann et al. 2014 ). Researchers considered SSCM social aspects too, with studies involving corporate social responsibility practices, fair labour and working conditions and etc. (Brammer and Walker 2011 ; Amann et al. 2014 ). However, now the three aspects of SSCM are taken as a whole. SSCM is a summation of economic, environmental and social factors (Carter and Rogers 2008 ; Seuring and Muller 2008a ) wherein sustainability choices of the organisation are extended to the supply chain. Thus, it involves the organisations and supply chain economic performance with the environmental and social factors. SSCM supports risk reduction and performance enhancement too (Brammer and Walker 2011 ) and affects corporate reputation on how an organisation responds to various environmental and social concerns to meet the expectations of its partners and customers (Hoejmose et al. 2014 ).

Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ) further elaborate that sustainability is critical for risk management in times of disruption, including climate change when fluctuation in resources demand and supply can cause uncertainty and proactive engagement can lower the risk in the supply chain. Organisations are interdependent on their stakeholders as per stakeholder theory, where key partners are engaged depending on the need and the equation prevalent between them (McKnight and Linnenluecke 2016 ). This engagement with suppliers and other stakeholders serves customers during various risks, including resource depletion and natural calamity (Zhang and Awasthi 2014 ; Bendul et al. 2017 ).

SSCM involves informed decisions through collaborations (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) between a focal company, suppliers and partners to yield benefits and value to its customers at minimum supply cost (Papageorgiou 2009 ) and depends on the network’s design for real-time management through planning and scheduling. Business continuity management involves risk assessment, continuity planning and steps for recovery (Azadegan et al. 2020 ). The literature also identifies the integration of triple pillars of sustainability with cooperation (Seuring and Muller 2008a ), coordination (Carter and Rogers 2008 ) and collaboration (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) for engagement with stakeholders, including internal and external to value add as per the requirement. Wankmüller and Reiner ( 2019 ) clarify that collaboration is the highest level of engagement between different entities in a supply chain built with cooperation and coordination between them. In times of disruption, collaboration supports the highest level of commitment and trust to create winning solutions, shared identity and combinations for those involved leading to customer satisfaction (Kaur and Bhardwaj 2019 ) for greater economic performance.

Furthermore, integration between different business systems and stakeholders supports the movement of information, material and capital, enhancing the organisations’ competitiveness and profitability (Ahi and Searcy 2013 ), and is a differentiator for greater brand recognition, resource optimisation, better customer service and competitiveness (Luthra et al. 2015 ). The engagement between different organisational customers, stakeholders and partners be for public, private, for-profit or not-for-profit organisations also gets increasingly complex with the increase in the number of partners and the size of entities (Roehrich et al. 2014 ). However, common goals, shared knowledge, leadership and governance mechanisms that focus on increased experimentation and innovation through collaboration help in managing the inter-organisational relationships. For the relationship between different entities of different sizes, the literature identifies that private or smaller organisations have the skill, knowledge and innovation capabilities. In contrast, larger or public organisations support social value creation, incentives for innovation, employment and competition to increase performance over time (Roehrich et al. 2014 ; 2019 ; 2020 ) while overcoming the barriers.

Engagement supports business continuity in disruption and risk management by planning strategy alignment up to the operational levels through information sharing, communication and adaptive organisational structures and processes (Herbane et al. 2004 ). Engagement is vital for efficient management of resources, planning for newer practices, disruption and climate change (Van Doorn et al. 2010 ; Zhang and Awasthi 2014 ). It also has external reasons for brand management and internal engaged partners and customers through shared identity (Vivek et al. 2014 ; Grewal et al. 2017 ; Dahlmann and Röhrich 2019 ). However, integration at the complete organisational level or SC level gets complex with multiple entities and partners (Roehrich et al. 2014 ; Azadegan et al. 2020 ) and thus affects business continuity. Schatter et al. ( 2019 ) further elaborate that fewer studies and approaches are in literature suggesting approaches for handling disruptions at the complete SCM level. Most business continuity studies are focused on IT industry or at the team level with fewer units.

The literature identifies different approaches for business continuity in SSCM and involves risk management and performance (Khalid and Seuring 2017 ; Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ), collaboration (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) and design (Wu and Pagel 2011 ; Busse et al. 2016 ) for better economic performance. Economic performance in disruption is sustained operations with efficient delivery times while working with minimal resources (Simatupang and Sridharan 2002 ; Sik Jeong and Hong 2007 ). And engagement depends on different motivations and dynamic expectations (Shepetuk 1991 ; Chen and Paulraj 2004 ) reflected in managing SSCM during disruption.

Enablers of customer engagement in SSCM for business continuity during COVID-19

Risk management and performance in supply chain management (rmp).

Disruption is a tremendous risk, and its management in SCM involves long-term economic, environmental and social sustainability (Markely and Davis 2007 ). Azadegan et al. ( 2020 ) emphasise the importance of risk management in business continuity planning. As per their research work, risk management involves engaged relationships and communication with a broader network to identify, assess, monitor and respond.

Risk management and performance in SSCM have more information exchange between customers—internal and external, to effectively utilise resources, profits, economic gains and skill development (Hofmann et al. 2013 ; Roehrich et al. 2014 ). Thus, it involves clarity of communication with clear procedures and technology to manage resources, tasks and capabilities (Simatupang and Sridharan 2002 ). It is a part of a strategy where the directions flow from top management up to the tactical levels. Roehrich et al. ( 2014 ) elaborate that risk and performance management is one of the salient features of SSCM, and organisations that cannot comply with sound environmental and social practices in their SCM have effects on survival and organisational reputation. Supplier base, reputation (Azadegan et al. 2020 ), market positioning and cost pressures enhance the risk in SCM, and decision-making is affected by different priorities of various customers, their motivation, commitment and contextual setting to contain risk and performance.

Collaboration of stakeholders, supplier evaluation by understanding customer expectations (Alicke and Strigek 2020 ) and alignment are strategies for enhanced performance (Kazancoglu et al. 2018 ) and risk management. In disruption, organisations usually work by enhancing more suppliers, thus multiple sourcing instead of single sourcing (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ) support, and increased suppliers enhance complexity to respond to manage risk (Roehrich et al. 2014 ). However, prior supplier evaluation and development with predefined criteria cater to the changing needs to manage disruption effectively. It is true both for lean and green SCM (Collin et al. 2009 ; Khalid and Seuring 2017 ).

Engagement with customers (Alicke and Strigek 2020 ) is also a means for more trust (Wankmuller and Reiner 2019 ), emotion, brand connection, shared identity and experience. It needs long-term relationship management to create the contextual setting for agility which implies being flexible, informed and responsive (COVID-19 Supply Chain Resources and Strategies 2020 ). It affects satisfaction, perceived value, expectations for business existence and continuity (Sik Jeong and Hong 2007 ; Won Lee et al. 2007 ; Van Doorn et al. 2010 ; Ellinger et al. 2012 ). Business continuity literature also suggests that integration of various entities and partners in SC has been less effective at organisational level than at a team level. This affects an organisation’s ability to respond to various disruptions in SC (Azadegan et al. 2020 ).

Collaboration (COL)

Collaboration between suppliers and the entire supply chain is an effective strategy to enhance competitive advantage (Won Lee et al. 2007 ; Khalid and Seuring 2017 ; Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) through improved customer understanding and intimacy. Disruption can be handled through enhanced and stored inventory but in the long term needs effective collaboration (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ), mitigating organisational inertia and involves strategic purchasing and information sharing with customers (both internal and external) to manage resources and forecast demand.

Wu and Pagel ( 2011 ) emphasise that sustainability is accomplished in the supply chain through the same processes used to enhance quality, reduce waste, improve effectiveness and etc. and get stakeholder satisfaction. In the short term, framing the decisions without direct advantages will lead to cost, but the collaborative approach focusing on each customer can accrue gain in the long term. Customer or supplier engagement also supports new product design and innovations (Dahlmann and Röhrich 2019 ; Gong et al. 2019 ). Decisions become the most crucial part as limited information leads to lesser attainment of the desired firm objectives. It becomes vital with global supply chains (Busse et al. 2016 ) while dealing with changes and uncertainties.

In SSCM, collaboration with strategic insights reduces ambiguity for action with many customers, suppliers and other stakeholders who have their objectives and thus lack a common goal. Maximising individual gains and profit alignment for different customers and suppliers in the entire SCM (Thron et al. 2006 ; Khalid and Seuring 2017 ) supports reducing lead time and reducing wastage through lesser inventory (Collin et al. 2009 ). It is an effective way for sustainability with more profits and local involvement of partners to manage relationships better, understand and respond to customers. Customer engagement supports through speed and agility to deliver products as per customer demand and preferences for SSCM. Minimising the impact of disruptions through collaboration is valid when the entire product life cycle is included, right from research and development to end product recycling and recovery, resulting in innovation (Treacy and Wiersema 1993 ; Butner 2010 ).

Design of supply chain management (DSC)

The design of SSCM considers standard procedures/technology for demand visibility to enhance resiliency for business continuity in times of disruption through agility, flexibility and collaboration (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ; Gong et al. 2019 ). Effective design of SSCM has various stakeholders for optimum utilisation of resources, inventory through a lesser focus on nodes. It involves the smoother flow of information and material as per customer needs and demand gauged through engagement to determine customer value thresholds for customer alignment as per the need. Engagement in SCM is defined in terms of basic, transactional and collaborative ones. Essential engagement pertains to the regular sharing of information followed by transactional information for specific outcomes. Collaborative engagement by design focuses on working with various customers to achieve common objectives (Dahlmann and Röhrich 2019 ) . In designing SSCM through effective communication, customer engagement strategies lead to greater transparency up to SCM’s sub-tier level. Furthermore, it supports to enhance resilience in times of disruption by more information exchange on-demand visibility to provide customer value (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ) with quality to target customers and segments with minimal friction (Treacy and Wiersema 1993 ; Ali et al. 2017 ; Gong et al. 2019 ). Jabbarzadeh et al. ( 2018 ) elaborate an optimum approach in SCM design which combines strategic, tactical and operational actions that need more focus from researchers.

Research gaps

Effective communication, decision-making and alignment of different customer motivations as per strategic imperatives support SSCM (Vivek et al. 2014 ). Strategic imperatives for SSCM are undertaken at the firm and the complete supply chain for new product developments, reengineering involving customer feedback (Alicke and Strigek 2020 ). Integration with effective governance mechanisms, structures and information sharing (Liu et al. 2012 ) supports business response and recovery of organisations from disruptions (Azadegan et al. 2020 ). However, various entities and partners in SC enhance the complexity and affect the ability of an organisation to respond to disruptions in an effective manner.

Kleindorfer and Saad ( 2009 ) further elaborate that the way an organisation responds to disruption falls majorly in two categories. One is to reduce the occurrence, and the other is to respond to the high-impact, low-frequency disruptions. However, the response is limited by the organisation’s ability and structure, and there is no one size all fit way. Trust, information sharing and economic performance for all will make the response effective. This can affect managerial ability for decision-making. When GDP, employment and corporate reputation get seriously hampered with disruption in emerging economies, outlining critical enablers is important for business continuity.

The literature suggests enablers of customer engagement for business continuity in a broader dimension include risk management and performance evaluation, collaboration and design using engagement through effective information sharing of strategic imperatives (Wu and Pagel 2011 ; Dahlmann and Röhrich 2019 ; Shashi et al. 2019 .; Song et al. 2020 ).

However, there is not much research evidence to identify and outline the customer engagement enablers from the three broader dimensions: risk management and performance evaluation, collaboration and design with a clear plan of action for managerial decision-making (Song et al. 2020 ; Tat-Dat Bui et al. 2020 ). In addition, SSCM focus on resource optimisation and agility can make SSCM vulnerable in times of disruption (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ). Effective decision-making in disruption needs clarity of enablers for organisational business continuity. However, tools for decision-making in uncertain situations are lacking (Schätter et al. 2019 ).

Moreover, the three broad dimensions have been used separately or combined with another at a broad level for business continuity. For instance, risk management and collaboration are explored (Beske and Seuring 2014 ) or the design of SSCM (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ). When constraints are high and resources are limited, identifying key customer engagement enablers to focus on can support managerial decision-making for business continuity, creating a winning scenario for all the entities of SCM. Customer engagement enhances business performance (Al-Dmour et al. 2019 ), and identification and prioritisation are vital.

To bridge the above gaps, twenty customer engagement factors under the three main dimensions of SSCM in times of disruption are identified with the help of extensive literature review and finalised by various deliberation with experts which are presented in Table 1 .

Research methodology

This study proposed a research framework to rank and prioritise customer engagement enablers in SSCM by determining the relative importance weight using rough SWARA (R-SWARA) as depicted in Figure 1 .

Representation of research flow

As discussed in the “Literature review” section, customer engagement enablers contribute to a resilient and sustainable supply chain. In this study, the enablers’ comprehensive know-how would facilitate decision-makers to make a robust decision by determining the relative importance of identified enablers of customer engagement in SSCM.

Rough stepwise weighted assessment ratio analysis (R-SWARA)

Zavadskas et al. ( 2018 ) first developed the R-SWARA method for determining the relative weights of the attributes by using rough numbers to reduce the subjectivity and uncertainty in complex decision-making problems. In recent times, R-SWARA has gained popularity among researchers and practitioners. It has been noticed lately that many studies address research problems by applying hybrid frameworks associated with MCDM (multiple criteria decision-making) and rough set numbers.

For instance, Zavadskas et al. ( 2018 ) used rough SWARA as a novel MCDM approach in the logistics sector under uncertainty. Vasiljević et al. ( 2018 ) employed to evaluate the criteria for supplier selection in the textile industry. Sremac et al. ( 2018 ) used the ranking of the third-party logistics provider. Stefanović et al. ( 2019 ) used rough SWARA to rank and prioritise the influential safety factors for developing occupational safety and health (OSH) climate. Ulutas et al. ( 2020 ) was used for the evaluation of selection criteria for logistics service providers. Contrary to other conventional MCDM (multiple criteria decision-making) techniques, R-SWARA is a facile and less tedious technique to capture experts’ knowledge and judgement rating to evaluate the criteria’s relative weights. This technique’s main advantage is that it requires fewer comparisons of criteria among themselves than other MCDM tools.

Additionally, this technique proved as a powerful technique to determine the significance ratio of identified criteria for making decisions. The R-SWARA method consists of the following steps, as mentioned by Zavadskas et al. ( 2018 ).

Step 1: Define a set of attributes or CSFs that participate or strive for the decision-making process.

Step 2: Establish a team of k experts who will rate or rank the attribute according to their relative importance, from the highly significant to the least significant attribute. Afterwards, S j is determined in such a way, starting with the second attribute or criterion, that we can determine how important criterion C 1 is compared to criterion C 1- n .

Step 3: In this step, every individual response of each expert ( K 1 , K 2 ……. K n ) is converted into a rough matrix ( C j ) using Eqs. ( 1 )-( 6 ) mentioned by Zavadskas et al. ( 2018 ).

Step 4: In this step, normalisation can be done of matrix RN ( C j ) in order to determine the matrix RN ( S j ) by using Eq. ( 8 ).

By using Eq. ( 9 ), we can determine the elements of matrix RN ( S j ).

The first element of matrix RN ( S j ), i.e. \( \left[{S}_j^L,{S}_j^U\right] \) = [1.00, 1.00], because j = 1. For other elements j > 1, Eq. ( 9 ) can be calculated using Eq. (4):

Step 5: In this step, calculate the matrix RN ( K j ) by using Eqs. ( 5 )-( 6 ).

Step 6: In this step, re-calculated matric RN ( Q j ) can be obtained by using Eqs. ( 7 )-( 8 ).

Step 7: Finally, relative importance weights matrix RN ( W j ) are calculated by using Eq. ( 9 ).

Data collection

In this study, qualitative and quantitative approach is utilised for analysing the enablers of customer engagement for SSCM. The study involved an extensive literature review and opinions of SCM experts from academics and industry practitioners for identifying and finalising various enablers of customer engagement for SSCM in an emerging economy context.

Following identification of the enablers of customer engagement for SSCM, questionnaires were administrated for data collection from managers and senior management of Indian manufacturing companies in healthcare supply chain. During the course of our research, the executives of healthcare supply chain company “XYZ” expressed a keen interest in our findings. To complete the expert questionnaire, we purposefully selected 20 senior and middle level managers with extensive expertise. The companies have more than ten crores per annum and have multinational operations and hence global supply chains. Furthermore, the experts had minimum work experience of 10 years in decision-making in the supply chain. A team of 20 experts consisting of logistics and supply chain managers, customer relationship managers, senior-level managers, social sustainability strategy managers and directors are used for the study. According to Bai et al. ( 2019 ), forming a 10-expert decision-making committee for an individual case firm is adequate to deliver reliable outcomes. Furthermore, despite the fact that there is a large body of research on the SWARA techniques in the literature, many studies include fewer than 10 experts (Büyüközkan et al. 2015 ; Li and Perçin 2019 ; Wen et al. 2019 ). Therefore, it is reasonable to select 20 experts in this study. The experts’ information is depicted in Table 2 .

Data analysis and results

Identification and finalisation of enablers of customer engagement for sscm.

In this phase, extensive literature review and experts’ judgement were employed to identify and finalise key enablers of customer engagement for SSCM. In this study, a team of twenty experts were invited to validate the identified list of enablers of customer engagement and were asked to enrich the final list by adding or deleting the enablers with their domain experience. After that, the final list of twenty enablers of customer engagement for SSCM has been categorised into three main dimensions, namely, risk management and performance in supply chain management (RMP), collaboration (COL) and design of supply chain management (DSC). Finally, the main dimension and sub-dimension enablers of customer engagement for SSCM are tabulated in Table 1 .

Calculation of the weights of enablers using rough SWARA method

In this step, expert ratings were collected through interviews and questionnaire surveys administered with the help of the prescribed method given by Zolfani et al. ( 2018 ). In this study, all twenty experts were asked to determine the most significant enabler compared to others. The expert rating score for each main dimension enabler is presented in Table 3 . Similarly, the ratings for all sub-dimension enablers of customer engagement for SSCM are tabulated in the Appendix Tables 9 , 10 , and 11 .

Based on the expert evaluation, eleven out of twenty experts identified risk management and performance in supply chain management (RMP), followed by eight out of twenty experts identified collaboration (COL) and only one expert identified design of supply chain management (DSC) stand the most crucial main dimension enablers of customer engagement for SSCM. The design of supply chain management (DSC) enablers were recognised as least important by thirteen experts, while collaboration (COL) was marked once as the least important enabler of customer engagement in the main dimension category. In the next step, converting all the individual ratings into rough group matrix RN ( C j ) is based on the above rating by using Eq. ( 1 ) and presented in Table 4 .

Afterwards, the value of normalised rough group matrix RN ( S j ) is obtained by employing Eqs. ( 2 ) and ( 3 ). In this step, the least enablers of customer engagement have the maximum value as per the value derived from the rough group matrix, and the most significant enabler is equal to one, while other enablers of the same RN ( C j ) matrix divided them by the maximum value, i.e. RN ( C DSC ) = [2.297, 2.885] in this case.

In this step, all the enablers of customer engagement of the normalised rough group matrix RN ( S j ) should be added by one except the value of RN ( S COL ) by applying Eq. ( 6 ). The obtained matrix RN ( K j ) is presented in Table 5 .

Next, all the values of matrix RN ( K j ) are recalculated by applying Eq. ( 8 ) in order to determine the value of matrix RN ( Q j ).

Finally, the relative importance weight and ranking of main enablers are obtained using Eq. ( 9 ), as shown in Table 6 .

The calculation of matrix RN ( W j ) is presented below.

Similarly, all the twenty experts were requested to rate the most significant and least significant among the sub-enabler category. Individual responses for all the sub-enablers by all the twenty experts are used to determine the weight of all the enablers of customer engagement in SSCM and presented in the Appendix Tables 9 , 10 , and 11 .

Finally, the global weight or global ranking of all the main and sub-dimension categories of enablers of customer engagement for SSCM was calculated using all the experts’ ratings to apply the above calculations in Table 7 .

Discussions and implications

The research outcome is summarised with a global ranking of enablers in Table 6 and sub-enablers in Table 7 to support managerial insights for effective decision-making in SCM disruption. As per Table 6 , the main enablers of collaboration are having the highest weight, followed by risk management and performance, with the last being the design of supply chain management (COL > RMP > DSC). This is also in affirmation with the earlier studies of Thron et al. ( 2006 ), Dahlmann and Röhrich ( 2019 ) and Sánchez-Flores et al. ( 2020 ), where researchers concluded that engagement for collaboration is vital for disruption management. Collaborative engagement by the decision-makers in an organisation with all the stakeholders, internal and external customers, supports effective decisions to manage uncertainty. Through engagement and by gauging the customer’s demand as reactive or passive, the focal organisation aligns its resources to add value through its respective product and services. Thus, the entire supply chain’s economic impact is managed to focus on the environmental aspect through social sustainability.

Furthermore, as per Table 7 , the sub-enablers for the main dimensions of collaboration, risk management and performance and design in supply chain management are ranked. The top five sub-enablers as per global ranking obtained by speed and agility to deliver products as per customer demand and preferences (COL1), followed by an emphasis on information sharing for effective collaborative planning including managing resources demand forecasting and replenishment (COL3), focus on target customers and segments (RMP4), strategic purchasing (COL6) and top management support and communication (RMP1).

In disruption, business continuity needs making the best use of available resources. Resources are scarce and get scarcer in times of extreme changes/disruption, with the behaviour of hoarding and poaching too rampant. The conventional risk management strategies include a narrow focus on one supplier, building an adequate inventory and supplier pool, and support business continuity. A strategic response through engagement for resource management and business continuity gains significance in extreme cases when there is a complete halt in demand and supply side like the one witnessed during the pandemic of COVID-19. Moreover, this scenario of complete halt from both the supply and demand side is now not rare, with changes in the environment and climate more frequent and rampant.

As per this study, effective and strategic engagement to gain the speed and agility to deliver products as per customer demand and preferences is ranked the most crucial sub-enabler for business continuity disruption. The second critical enabler emphasises information sharing for effective collaborative planning including managing resources, demand forecasting and replenishment. This inference gains a perspective for the first sub-enabler as information sharing has to be adequate to gain agility when every step, especially in disruption, has cost attached in scarce resources and lost opportunities. Focus on target customers and segments (third critical enabler as per Table 7 ) can support vital information for effective organisational deliveries. For instance, as had been the case in healthcare in the pandemic of COVID-19, more than equipment for surgeries, the target segment like the hospitals needed protective equipment to safeguard against the infection (Abdelnour et al. 2020 ; Alicke and Strigek 2020 ). Focus on target customers supports business continuity as all resources; strategies are aligned with more agility for value addition, including strategic purchasing (fourth important sub-enabler as per Table 7 ). It needs top management commitment and focus (the fifth critical enabler as per Table 7 ).

The ranking of enablers for SSCM is interpreted as they may not be critical for business continuity in disruption but are crucial for managing engagement that supports SSCM (Sierra-García et al. 2015 ). “Demand and delivery management” (sub-enabler ranked 6th), “firm’s strategy for competitive advantage” (sub-enabler ranked 7th), “focus on quality” (sub-enabler ranked 9th), “maximisation of individual profits” (sub-enabler ranked 14th) and so on are enablers for enhancing engagement for SSCM. Customer’s needs and alignment of individual motives and profits with the overall firm strategy create a competitive advantage for long-term business continuity. Thus, focus on supplier evaluation with pre-defined criteria (enabler ranked 10 as per Table 7 ) for long-term collaboration will support disruption and achievement of other firm objectives. The last rank in all the sub-enablers is the contextual setting for agility (RMP8). The contextual setting for agility is the broader part that caters to stepping back and taking stock of the situation for aligning the initiatives. Speed and agility are essential while managing disruptions, and hence contextual setting may affect the needed momentum. In all, effective strategic focus on engagement in the long term can support business continuity through appropriate processes, technology and innovation in disruption and achieving long-term objectives.

The study’s outcome complements Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ) sustainability framework and stakeholder theory (Hofmann et al. 2013 ) and is consistent with research studies (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ) for SSCM in times of disruption. It focuses on the social aspects of engagement with stakeholders using focused usage of available resources to gain economic sustainability. It will ensure business continuity through effective managerial decision-making in emerging economies as a part of the global supply chain by focusing on agility with information per customer requirements.

Finally, this study, utilising rough SWARA and collaboration (COL), is positioned as the most significant among all the main enabler category. In this manner, the relative importance weight of collaboration enablers is altered with the incremental addition of 0.1 from run 1 to 9 (Kumar and Dixit 2019 ; Kaushik et al. 2020 ; Kumar et al. 2020 ). Accordingly, the changes have to be made for other main enablers simultaneously. The relative importance weights of all other main dimension enablers using sensitivity investigation are presented in Table 8 . It can be therefore deduced that the empirically derived framework in this study is quite robust in nature as the experts’ judgement was not affected by variations in the weights of different criteria.

Implications of research

Management of disruption for business continuity is essential. Disruption management at different points of time in SCM entails responsiveness, practices for the outcomes leading to enhanced performance and integration. SCM focuses on the flow of information, resources and services and seeks stakeholder engagement for improved efficiency and performance (Ahil and Searcy 2013 ). Resources are scarcer in disruption and uncertainty makes decision-making difficult due to the complexity of situations along with time pressures to respond. Thus, focused value addition for greater output from the availabilities per customers’ need enhances the performance and efficiency of SCM for business continuity through strategic focus to and with customers.

Disruptions, including pandemics like COVID-19 and climate change for SSCM, need organisational agility and effective, timely decision-making with customers and stakeholders. Sustainability in SCM involves three key aspects, including the performance activities and the value provided with SCM components (Ahil and Searcy 2013 ), focusing on the relationship with internal components for external customers. Customer engagement is presided by awareness through information flow to effectively manage resources in regular times and extremities like the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research worked on the gaps for clear criteria to decision-makers for response in disruption. It ranked customer engagement enablers in their importance through literature review and expert opinion in the broad dimension of risk management and performance, collaboration and design using research methodology through R-SWARA. Customer engagement thrives on strategic focus and information sharing through effective collaboration to support business continuity across nations’ boundaries when nothing is certain and global supply chains can falter any moment due to vivid scenarios. The research and its ranking of enablers of customer engagement support managerial decision-making by identifying the enablers for business continuity. Speed and agility to deliver products as per customer demand and preferences, followed by emphasising information sharing for effective collaborative planning, including managing resources, demand forecasting and replenishment, will create value addition in SCM to continue the business in complex and uncertain scenarios including in different time spans, industries and economies as supply chains are integrated.

Implications to theory

In disruption for business continuity in SC, trust, information sharing and economic performance make the response effective (Kleindorfer and Saad 2009 ) with different customers (internal and external). However, the increase in the number of entities and thus the complexities affect the response and engagement. It is easier to maintain it at the team level than at the organisational level in SC (Azadegan et al. 2020 ). The literature identifies three broad dimensions used separately or combined with another for business continuity. For instance, risk management and collaboration are explored (Beske and Seuring 2014 ) or the design of SSCM (Jabbarzadeh et al. 2018 ). When constraints are high and resources are limited, identifying key customer engagement enablers to focus on can support managerial decision-making for business continuity, creating a winning scenario for all the entities of SCM.

The research builds on the earlier approaches to sustainability through the framework of Carter and Rogers ( 2008 ) for economic performance through non-economic aspects, including environmental and social aspects with resource constraints. In addition, the research extends stakeholder theory (Hofmann et al. 2013 ) to SSCM in emerging economies where different stakeholders can influence an organisation’s response to different stimuli. There is a dearth of studies in emerging economies on SSCM involving resource management and ways to overcome the challenges in uncertainty (Sánchez-Flores et al. 2020 ). The study supports business continuity with emerging economy aspect through ranking customer engagement enablers. Enhanced sustainability through customer engagement mitigates disruption in SCM for both the production and supply sides. A collaborative model of engagement with various customers and other measures, including enhanced production capacity, is accomplished by several suppliers with limited resources, including logistical and workforce. Demand visibility and customer preferences through effective collaboration with various stakeholders bring clarity for more extraordinary value addition. This research outlines the critical customer engagement enablers, and focusing on them can effectively manage extreme disruption.

Implications to practice

The enablers outlined in this study to manage disruption in SSCM will support managerial decision-making in extremities of disruption like COVID-19 and climate change scenarios. The engagement enablers ranked in the survey give a direction to decision-makers/managers to focus on critical enablers for business continuity implementation in emerging economies. It also indicates enablers whose performance can be delayed in the disruption. Engagement with internal and external customers supports manufacturers or producers in more resilient ways in extremities and disruptions when decision-making gets complex due to pressures in time and performance with limited resources.

The study is also significant for managing climate change disruptions by providing strategic impetus through ranked enablers to the management to focus on customer engagement to build long-term resilience in the supply chain. Agility and flexibility through a collaborative approach can be built-in SCM through information sharing, focusing on target customers involving forecasting demand, innovation, refilling, ordering products and inventory. Sustainable use of resources is not just a need but is a crucial component for business continuity in emerging markets to prepare for more contingencies, including the recession, pandemic and muted demand with focused value addition and appropriate usage of resources.

Unique contribution of the research

This study’s contribution is the ranking of enablers of customer engagement for SSCM to manage contingencies and disruption like COVID-19. Customer engagement enablers for SSCM had not been ranked earlier in any study to provide a framework of enablers to practitioners when deciding and implementing a response to manage a disruption through SCM. The practitioner’s response through the enablers identified in the study considers the limitation of resources and workforce, focusing on target customers through a collaborative approach. Collaborative engagement and approach will support moving the available resources fast as per clear demand identification. It has substantial implications for decision-makers and practitioners to support their efforts of business continuity. Resources are always limited, and SSCM will need to enhance resource utilisation while maintaining organisational, economic performance and supply chain. Collaborative engagement with local communities, suppliers, employees and customers will support long-term contingency planning in SSCM. Internal and external customers are the crucial components in S.C., and their involvement affects the organisational response to uncertainties through decisions and practices.

Conclusion and limitations of research

Management of disruptions like COVID-19 is vital for business continuity as organisations; individuals need to work with limited resources and agility to cater to fluctuating customer demands and preferences. There is a lack of research in emerging economies to evaluate resource consumption and strategies to respond to the crisis. Typically in emerging economies, apart from pandemics, climate changes like earthquakes and floods too can affect the organisational deliverables. Moreover, in disruption, every business model gets relooked for its deliverables and efficiency. It becomes essential in emerging economies from a business perspective, with 40% GDP coming from SME, who cannot survive without economic performance or financial support. They lack the financial prowess to survive long term and knowledge to draft a thoughtful organisational response. The entities in the entire supply chain are affected without a strategy for business continuity. Business continuity is also a strategy for brand reputation and competitive advantage in SSCM.

Resources are scarce, and disruption creates new behaviours across industries, including hoarding and demand stagnation, and it tilts the balance of the entire supply chain. Therefore, focusing on supplier nodes is risky, and diversification with customer engagement and focus is crucial for effective deliverables and SSCM. The research used an extensive literature review and expert recommendation to identify critical customer engagement factors necessary for SSCM. The enablers in broad dimensions of risk management and performance, collaboration and design in SSCM were further evaluated using rough SWARA. Furthermore, the different enablers were ranked to manage disruption and for business continuity in SSCM.

The first contribution of the research is identifying enablers from the broad dimensions where at times in literature it is risk management and performance, collaboration or design of SSCM. The theoretical contribution of the research is building on the sustainability framework by Cater and Rogers ( 2008 ), emphasising economic performance with non-economic factors, including social and resource utilisation.

As per the research, collaboration is a key enabler and a differentiating factor for businesses to tide over disruption. Stakeholders can support the agility to move as per customer demand and preferences for a faster communication, crucial information sharing, execution and bottlenecks to manage disruption for business continuity in the entire supply chain. It is the critical contribution of research to support decision-makers through customer engagement across the entire supply chain. It can provide a strategic way to respond to the crisis with collaboration for quick decisions. Agility is needed in times of uncertainty. Thus, focusing on target customers’ needs can more engagingly move the entire supply chain, thus supporting the efforts. Over the years, SCM has evolved from local to global supply chains and is now increasingly focused on local to eye the global. Customers, including the internal and external stakeholders, employees and investors, play a significant role in SCM. Thus, an effective engagement strategy can further support the efforts to create the case for economic, environment and social sustainability in the management of the supply chain. Resource utilisation through collaborative approaches will make the entire process more efficient and reduce waste while also bringing economic gains even to the weaker links in the supply chain, which could not have survived if they had worked alone. Moreover, emerging economies need to focus on supply chains for positive economic gains. Organisations need measures to enhance business continuity and operations while also taking care of their stakeholders, environment and profits. The research is also crucial for other emerging countries and organisations with supply chains across the world. Responding to uncertainties with a clear focus on target customer needs can support creating agility in the global supply chain.

The research is limited by its sample size and scope of industries. The research methodology was adopted in emerging economies as part of the global supply chain. It can be extended to other sectors, including agriculture and service industries, to validate the study’s outcome. Researchers can also extend the study for varied SCM disruptions with practical implementation and outline the challenges for more development in research from emerging economies and global perspectives. Furthermore, the expert opinion can be biassed concerning experience and their work. Different hypotheses for the enablers in other industries with different sample sizes and methodologies, including multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) like A.H.P. and A.N.P., can evaluate the enablers and effects to substantiate customer engagement for SSCM in times of disruption like COVID-19.

Data availability

All the data have been provided in the manuscript.

Abdelnour A, Babbitz T, & Moss S (2020) Pricing in a pandemic. Navigating the COVID-19 crisis. Mckinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/pricing-in-a-pandemic-navigating-the-covid-19-crisis #

Ahi P, Searcy C (2013) A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J Clean Prod 52:329–341

Google Scholar

Al-Dmour HH, Ali WK, Al-Dmour RH (2019) The relationship between customer engagement, satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management 10(20). https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCRMM.2019040103

Amann M, Roehrich JK, ßig EM, Harland C (2014) Driving sustainable supply chain management in the public sector: the importance of public procurement in the EU. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19(3):351–366

Azadegan A, Syed TA, Blome C, & Tajeddeni K (2020). Supply chain involvement in business continuity management: effects on reputational and operational damage containment from supply chain disruptions. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-08-2019-0304

Ali I, Nagalingam S, Gurd B (2017) Building resilience in S.M.E.s of perishable product supply chains: enablers, barriers and risks. Prod Plan Control 28(15):1236–1250

Alicke K & Strigek A (2020) Supply chain risk management is back. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/supply-chain-risk-management-is-back

Attaran M, Attaran S (2007) Collaborative supply chain management. Bus Process Manag J 13(3):390–404

Bag S, Telukdarie A, Pretorius, J. H. C., & Gupta, S. (2018). Industry 4.0 and supply chain sustainability: framework and future research directions. Benchmarking: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-03-2018-0056 .

Bai C, Kusi-Sarpong S, Badri Ahmadi H, Sarkis J (2019) Social sustainable supplier evaluation and selection: a group decision-support approach. Int J Prod Res 57 (22):7046–7067

Bendul JC, Rosca E, Pivovarova D (2017) Sustainable supply chain models for base of the pyramid. J Clean Prod 162:S107–S120

Beske P, Seuring S (2014) Putting sustainability into supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19(3):322–331

Brammer S, Walker HL (2011) Sustainable procurement in the public sector: an international comparative study. Int J Oper Prod Manag 31(4):452–476

Building a more resilient I.C.T. Supply chain: lessons learned during the Covid-19 pandemic. (2020) Retrieved from https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/lessons-learned-during-covid-19-pandemic_508_0.pdf

Busse C, Meinlschmidt J, Foerstl K (2016) Managing information processing needs in global supply chains: a prerequisite to sustainable supply chain management. J Supply Chain Manag 53(1):87–113

Büyüközkan G, Kayakutlu G, Karakadılar İS (2015) Assessment of lean manufacturing effect on business performance using Bayesian Belief Networks. Expert Syst Appl 42(19):6539–6551

Butner K (2010) The smarter supply chain of the future. Strateg Leadersh 38(1):22–31

Caldwell N, Roehrich JK, George G (2017) Social value creation and relational coordination in public-private collaborations. J Manag Stud 54(6):906–928

Carlsson-Szlezak P, Reeves M & Swartz P (2020) Understanding the economic shock of coronavirus Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/03/understanding-the-economic-shock-of-coronavirus?utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter_daily&utm_campaign=mtod_notactsubs&utm_term=subacq_buyeracq_nsubarticle

Carter CR, Rogerss DS (2008) A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 38(5):360–387

Cerullo V, Cerullo MJ (2004) Business continuity planning: a comprehensive approach. Inf Syst Manag 21(3):70–78

Chen IJ, Paulraj A (2004) Towards a theory of supply chain management: the constructs and measurements. J Oper Manag 22(2):119–150

Chopra S, Meindl P, Kalra DV (2011) Supply chain management: strategy, planning, and operation. Pearson Education, Delhi, India

Collin J, Eloranta E, Holmström J (2009) How to design the right supply chains for your customers. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 14(6):411–417

COVID-19 supply chain resources & strategies (2020). Retrieved from https://www.inboundlogistics.com/cms/article/COVID-19-supply-chain-resources-and-strategies/

Dahlmann F, Röhrich JK (2019) Sustainable supply chain management and partner engagement to manage climate change information. Bus Strateg Environ 28(8):1632–1647

Degnarain N (2020) Coronavirus crisis shines light on sustainability in global pharma and medical supply chain. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nishandegnarain/2020/03/21/coronavirus-crisis-shines-light-on-sustainability-in-global-pharma-and-medical-supply-chain/#1138b43f5495

Elkington J (1999) Triple bottom line revolution: reporting for the third millennium. Australian CPA 69(11):75–79

Ellinger A, Shin H, Magnus Northington W, Adams FG, Hofman D, O'Marah K (2012) The influence of supply chain management competency on customer satisfaction and shareholder value. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 17(3):249–262

Evans S, Vladimirova D, Holgado M, Van Fossen K, Yang M, Silva EA, Barlow CY (2017) Business model innovation for sustainability: towards a unified perspective for creation of sustainable business models. Bus Strateg Environ 26(5):597–608

Fischl M, Scherrer-Rathje M, Friedli T (2014) Digging deeper into supply risk: a systematic literature review on price risks. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19(5/6):480–503

Grewal, D., Roggeveen, A., L, Sisodia, R., & Norfalt, J. (2017). Enhancing customer engagement through consciousness. J Retail, 93(1), 55-64

Gong M, Gao Y, Koh L, Sutcliffe C, Cullen J (2019) The role of customer awareness in promoting firm sustainability and sustainable supply chain management. Int J Prod Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.01.033

Govindan K, Shaw M, Majumdar A (2021) Social sustainability tensions in multi-tier supply chain: a systematic literature review towards conceptual framework development. J Clean Prod 279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123075

Gouda SK, Saranga H (2018) Sustainable supply chains for supply chain sustainability: impact of sustainability efforts on supply chain risk . International Journal of Production Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1456695

Herbane B, Elliott D, Swartz EM (2004) Business continuity management: time for a strategic role? Long Range Plan 37:435–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2004.07.011

Article Google Scholar

Hoejmose SU, Roehrich JK, Grosvold J (2014) Is doing more, doing better? The relationship between responsible supply chain management and corporate reputation. Ind Mark Manag 43(1):77–90

Hofmann H, Busse C, Bode C, Henke M (2013)Sustainability-related supply chain risks: conceptualization and management. Bus Strateg Environ 23(3):160–172

Ivanov D, Dolgui A (2020) A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Prod Plan Control:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1768450

Jabbarzadeh A, Fahimnia B, Sabouhi F (2018) Resilient and sustainable supply chain design: sustainability analysis under disruption risks. Int J Prod Res:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1461950

Jabbour CJC, & Jabbour ABLDS (2020)COVID-19 is contaminating the sustainability of supply chains. Retrieved from https://www.scmr.com/article/covid_19_is _contaminating_the_sustainability_of_supply_chains

Jayaram K, Leke A, Ooko-Ombaka A, Sun YS (2020) Tackling COVID-19 in Africa. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/tackling-covid-19-in-africa?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck&hlkid=c686e4fe68c345638c2c7740bc6592fe&hctky=10256918&hdpid=03e33a3d-14f6-4dc7-9df9-90a721d373fd

Kalra J, Lewis M, Roehrich J (2021) The manifestation of coordination failures in service triads. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 26(3):341–358

Kaur A & Bhardwaj R (2019) Sustainable supply chain through greater customer engagement, green practices and strategies in supply chain management, Syed Abdul Rehman Khan, IntechOpen, https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82485 . Retrieved from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/green-practices-and-strategies-in-supply-chain-management/sustainable-supply-chain-through-greater-customer-engagement

Kaushik V, Kumar A, Gupta H, Dixit G (2020) Modelling and prioritising the factors for online apparel return using BWM approach. Electron Commer Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10660-020-09406-3

Kazancoglu I, Sagnak M, Mangla SK, Kazancoglu Y (2020) Circular economy and the policy: a framework for improving the corporate environmental management in supply chains. Bus Strateg Environ 30. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2641

Kazancoglu Y, Kazancoglu I, Sagnak M (2018) A new holistic conceptual framework for green supply chain management performance assessment based on circular economy. J Clean Prod 195:1282–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.015

Khalid RU, Seuring S (2017) Analysing base-of-the-pyramid research from a (sustainable) supply chain perspective. J Bus Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3474-x

Kilpatrick J & Barter L (2020) Deloitte. COVID-19-managing supply chain risks and disruption. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ca/Documents/finance/Supply-Chain_POV_EN_FINAL-AODA.pdf

Kiron, D., Kruschwitz, N., Haanaes, K., Reeves, M., Kehrbach, S.K.F., & Kell G. (2015). Joining forces: collaboration and leadership for sustainability. Retrieved from https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/joining-forces/

Kleindorfer PR, Saad GH (2009) Managing disruption risks in supply chains. Prod Oper Manag 14(1):53–68

Kumar A, Dixit G (2019) A novel hybrid MCDM framework for WEEE recycling partner evaluation on the basis of green competencies. J Clean Prod 241:118017