- Lightweight PPM Software

- PPM Maturity Assessment

- PPM Training Videos

PPM 101 – Good Project Portfolio Governance Delivers Superior Results

Strong project portfolio governance is the number one success factor for making portfolio management successful. Unfortunately, most companies struggle with governance. In fact, when you hear the word ‘governance’, what comes to mind? Do you think of bureaucracy, lots of meetings with few or no decisions, unclear expectations, poor accountability, strife between decision makers, inconsistent decision making? These issues are really just the symptoms of poor governance. In this post, we are going to focus on what project portfolio governance is and why it is important and provide success factors to help your governance teams improve their governance processes.

“Effective IT governance is the single most important predictor of the value an organization generates from IT”¹

What is Project Portfolio Governance?

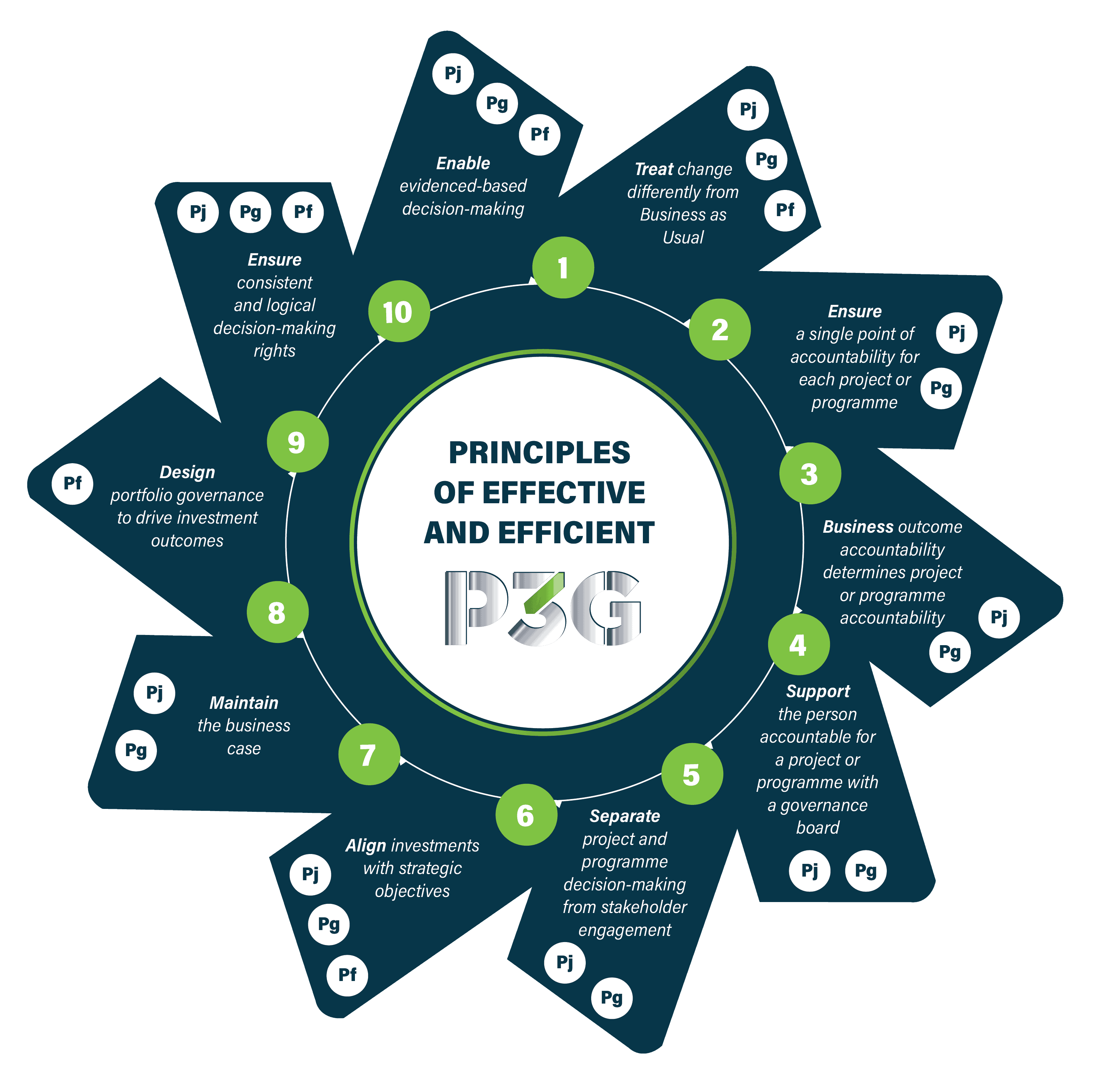

At its core, project portfolio governance is about strategic decision making. When we talk about project portfolio governance we are referring to the governance of all projects in the portfolio. The graphic below highlights that all four components of the portfolio management lifecycle depend on good project governance. From a portfolio management perspective many of the critical decisions involve project selection (Defining the Portfolio), prioritization and resource allocation ( Optimizing Portfolio Value ), project performance (Protect Portfolio Value) and realizing project benefits (Delivering Portfolio Value). Portfolio governance is the foundation of project portfolio management.

According to Peter Weill and Jeanne Ross, experts in information technology governance, governance can be defined as “specifying the decision rights and accountability framework to encourage desirable behavior…”. Clearly, this refers to the people making decisions, a process for making decisions, and accountability to help ensure that good decisions are made.

“Portfolio management without governance is an empty concept” ²

In practice, the tension is about how to make project portfolio governance both effective and efficient. Project portfolio governance can be effective but requires a significant amount of time from project teams to collect data, the Portfolio Manager to create reports, and for the governance committee to sift through the reports and data to make better decisions. Project Management Offices (PMO’s) may also take a “lean” approach to project portfolio governance that is apparently efficient that requires little effort from the governance committee, but is inadequate or completely ineffective. Our goal is to balance effectiveness against efficiency to ensure that the portfolio is properly managed and delivering maximum value.

Why is Project Portfolio Governance Important?

Project portfolio governance is important because it is the foundation of all portfolio management activities. According to Howard A. Rubin, a former executive vice president at the Meta Group, “a good governance structure is central to making portfolio management work.” Hence, well-defined and properly structured governance is critical to manage the portfolio. Let’s define good portfolio governance as having the right people making good strategic decisions with the right information at the right time.

- The right people – having the right decision makers means having people at the right level of authority and breadth of knowledge to make decisions. Having the wrong people involved (or missing the right people) means that decision quality is compromised, a decision can’t be made or must be revisited later, or that a decision will be challenged. None of these are desirable outcomes and should be avoided. Empowering the right decision makers within the organization is very important. In addition, different levels of management may participate in different types of portfolio decision making. Identifying which people make certain decisions is part of having the right people for project portfolio governance.

- Good strategic decisions – the goal of portfolio management is to maximize organizational value, and good portfolio management by definition is about making trade-offs, which means not everything can get done. Good strategic decisions include “no” or “no, not right now”. Saying “no” is a critical success factor for project portfolio governance. If the governance committee approves most projects or makes everything a priority, portfolio value is diminished. It is also critical for the governance team to agree on HOW it will make decisions.

- The right information – even if the right decision makers are present and capable of making good portfolio decisions, having too much or too little information frustrates the decision-making process. Not only do decision makers need to know how to use portfolio data, but they need the right data, otherwise they will make sub-optimal portfolio decisions. Governance includes the processes for collecting quality data in a timely way.

- The right time –a governance team needs to meet on the right cadence to address portfolio matters. Project approvals, prioritization, status reviews, capacity planning, all need to be conducted on a consistent cadence. This doesn’t mean that all of these activities have the same cadence, only that they occur on a consistent basis to ensure the portfolio is properly managed.

“Good governance design allows enterprises to deliver superior results on their [project] investments.” ¹

The Portfolio Governance Team

Setting up a portfolio governance team is a critical first step in establishing portfolio governance. Until there is a governance team, there is no governance. The composition of the portfolio governance team is important as the effectiveness of portfolio governance and strategic decision making is directly correlated with the ability of the governance team to make decisions that carry weight and will be respected across the organization. Governance teams composed of junior leaders often need their decisions “blessed” by one or more senior leaders before they are really approved. This is considered weak governance.

Organizations that don’t take this serious will miss the mark on portfolio management – get the right leaders together who can effectively make serious strategic decisions for the organization. After all, we’re talking about making critical strategic decisions that impact the organization’s ability to accomplish strategic goals; it’s worth putting in some time and energy to make it work. Sadly, many organizations go through the motions of governance without ever really getting the benefit of portfolio management. Moreover, it’s easier for everyone to avoid contention by saying ‘yes’ to proposals rather than have a healthy debate over whether projects should be approved and how they should be prioritized.

Effective portfolio governance relies on an effective portfolio governance team. Simply bringing senior leaders together does not automatically constitute a team. The governance team should have limited membership but adequate representation of organizations impacted by projects in the portfolio. Each member should bring something unique to the team to add value to the governance team.

The Accountability Framework

In order to achieve support results on project investments, it is paramount that good strategic decisions are consistently made and then properly executed. In order to ensure that good decisions are made that maximize portfolio value and benefit the organization, accountability mechanisms need to be put in place. Accountability may also be synonymous with fair and equitable processes as well as transparency. ‘Accountability’ and ‘accountable’ have strong positive connotations; they hold promises of fair and equitable governance. It comes close to ‘responsiveness’ and ‘a sense of responsibility’, a willingness to act in a transparent, fair, and equitable way. Governance teams must then demonstrate their accountability for the appropriate, proper and intended use of resources. This is what project portfolio governance is about. Furthermore, it is good leadership that drives accountability. True leaders hold decision makers accountable for their decisions.

The diagram below captures the three elements of the accountability framework.

- Leadership to drive accountability

- Governance as the framework which enables accountability

- A shared vision with strategic goals to demonstrate accountability

The rest of this post will focus on the first two elements and will close with critical success factors for effective and efficient project portfolio governance.

Leadership Drives Project Portfolio Governance Accountability

Leadership is at the heart of governance for it is people who make decisions, but not all decision makers are leaders, and by extension, not everyone on a governance team is a leader. Yet, when the governance council has true leaders and this leadership team truly functions as a team, then strong portfolio management is finally possible.

Because many governance teams do struggle to provide leadership to the organizations they are serving, it is appropriate to bring up Patrick Lencioni’s model on the five dysfunctions of a team . The model is shown below with some brief commentary taken from his book, The Advantage ³.

Five Dysfunctions of a Team

- The absence of trust – “The only way for teams to build real trust is for team members to come clean about who they are, warts and all.” The absence of trust manifests itself in project portfolio governance when team members are afraid to share their points of view about projects. If most of the governance team wants to approve a project, but one person has a different point of view and simply goes along with the rest of the team and doesn’t share their thought, there is an absence of trust on the team. This leads to the second dysfunction.

- The fear of conflict – “When there is trust, conflict becomes nothing but the pursuit of the truth, an attempt to find the best possible answer”. I love Lencioni’s quote here because conflict is not directed toward other individuals but is for the purpose of finding the best possible answer. Portfolio management is a multi-faceted discipline and everyone on a governance team sees things with a different lens, which is why everyone’s input is necessary. Tragically, governance teams compromise decision quality for the sake of maintaining an artificial sense of harmony among the team. Some corporate cultures avoid conflict and pay a price for it or the governance team owner shies away from conflict and ends up avoiding valuable discussion as a result. The fear of conflict stymies people and brings out mediocrity from a governance team.

- The lack of commitment – “When leadership teams wait for consensus before taking action, they usually end up with decisions that are made too late and are mildly disagreeable to everyone. This is a recipe for mediocrity and frustration”. With trust and the pursuit of the truth, governance team members will buy in and decisions are more likely to stick.

- The avoidance of accountability – “To hold someone accountable is to care about them enough to risk having them blame you for pointing out their deficiencies.” The point here is not to point the finger but have the freedom to hold one another accountable. In the context of portfolio management, I have heard governance teams say that they are at maximum resource capacity yet try to squeeze in “one more project”. Don’t say one thing and do another. Another example might be in the context of Phase-Gate where a project does not meet the minimum thresholds for approval yet one or more governance team members feel strongly to approve it any way. If the governance team holds themselves accountable, they can at least have the discussion as to why an exception is being made for the approval.

- Inattention to results – “No matter how good a leadership team feels about itself, and how noble its mission might be, if the organization it leads rarely achieves its goals, then, by definition, it’s simply not a good team.” Enough said – results matter. The portfolio governance team must see the forest (the portfolio) and the trees (the projects) and be successful at both levels.

Governance Framework to Enable Accountability

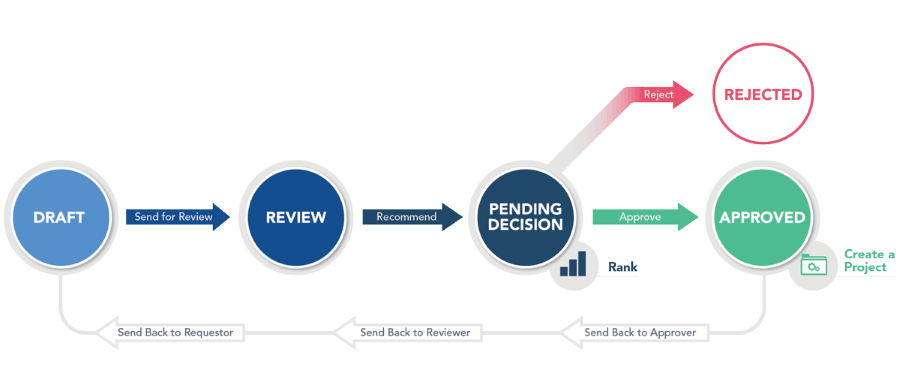

While strategic decision making is at the heart of project portfolio governance, a number of processes are needed to support and complement decision making. Processes such as work intake , Phase-Gate , prioritization , and capacity planning processes provide the right information to support the governance team. Setting up these processes effectively and efficiently is also very important to make portfolio management work.

By getting agreement on these governance processes among decision makers, the governance team can utilize this framework in a more harmonious and successful manner. “Those [organizations] with effective governance have actively designed a set of [governance] mechanisms (committees, budgeting processes, approvals, and so on) that encourage behavior consistent with the organization’s mission, strategy, values, norms, and culture” (Weill 2). One of the key words in this sentence is ‘actively designed’. Successful organizations actively design their governance processes to align with their vision, mission, strategy, and culture. By extension, those organizations that haphazardly design their governance processes may struggle and even fail to make good investment decisions. Effective governance is the single most important predictor of the value an organization generates from its portfolio.

Minimal Viable Governance

When it comes to developing governance processes, the key is to develop the minimal amount of governance that will help effectively manage your projects and portfolios. We can refer to this as “minimal viable governance”. This is a new term analagous to a minimal viable product (MVP). The idea is to right-size governance to match the size and complexity of your portfolio. Most organizations over-engineer their governance process and it becomes bureaucratic. However, when organizations have little or governance processes in place, it becomes chaotic. One major objection we have heard over the years related to project portfolio management is that it is bureaucratic. The reality is that project portfolio management is only bureaucratic if you have the wrong infrastructure. We can use the diagram below to highlight this.

Small portfolios – For organizations with small portfolios, simple governance is needed. Basic mechanisms about how to approve projects and quickly prioritize them are likely sufficient. This can be likened to a simple stop sign that helps control the flow of traffic.

Medium-sized portfolio – for organizations with a moderate sized portfolio, additional processes may be needed. Specific status reporting and resource management along with Phase-Gate processes may be warranted. This is likened to have traffic lights with additional signage to control the flow of more traffic.

Large portfolio – organizations with a very large portfolio can be likened to a California freeway with multiple lanes of traffic. Stricter processes around Work Intake , Phase-Gate, resource management, portfolio planning and dependency management are warranted in order to protect the portfolio and improve strategic decision-making quality.

Large-scale transformation – in rare cases, large companies take on transformational initiatives that are too big to fail and require a level of rigor not needed for the typical project portfolio. In these cases we see very strict and very prescriptive processes dictate how projects should be run. The air-traffic control analogy is used here because airplanes are controlled in a strict way for safety reasons, a lot of governance and infrastructure is required for airplanes to take off, land, and be maintained. Although some experts like to compare portfolio management with air traffic control, in actuality, very few companies need this level of rigor.

Common Objections to Governance

1) “it will slow us down”.

I have heard companies say that adding governance processes will slow down projects. This is like saying stop signs and stop lights slow down traffic. Yes, in a sense, vehicles need to stop at times to make way for other vehicles, but not having traffic lights and stop signs will not make traffic flow faster; it will make it worse. This is an apt analogy for portfolio governance. Project teams may not have to complete as many governance reviews, but without governance there is no way to prioritize work and manage resource capacity. In fact, without governance, more projects will be authorized than can be reasonably completed and will delay the completion of critical projects, just like having a large flow of vehicle without traffic lights will result in gridlock. This is why organizations need to be deliberate with how much governance is needed.

Too much process becomes bureaucratic, but too little process becomes chaotic. The fact is, project portfolio management is only bureaucratic if you have the wrong infrastructure.

2) “we use agile around here”.

A common area of resistance comes from the notion that governance is contrary to agile principles. This is not accurate. The Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) refers to “lean governance” and “lightweight governance”. Solution trains, agile release trains, and program increments are examples of a structure (governance) that enables agile delivery. Furthermore, some level of senior leadership decision making is still needed to firstly determine whether a project (waterfall or agile) should even be done. High-level estimates can still be provided during an intake process to help leadership determine whether it is the right project to do. Teams can leverage various project frameworks and methodologies to do the work right.

Project Portfolio Governance Success Factors

We conclude with a short list of success factors to help improve project portfolio governance. Many of these touch on topics covered earlier in the post, but are based on years of consulting experience.

- Active engagement – coming prepared, being present, asking questions, proposing solutions

- Open, honest, transparent discussions – working comfortably through conflict to find the best possible answer

- Ability to make tough trade-off decisions – preventing misaligned projects from draining critical resources

- Shifting from a singular project view to an aggregate portfolio view – always asking ‘how will this impact our portfolio?’

- Focus on optimizing portfolio value – finding the right combination of projects that unlock greater portfolio value

- Balancing long-term and short-term needs – not always choosing the easy projects

- Communicating a consistent message – reinforcing business goals and objectives; demonstrating this through results

Does any of this ring true for you? If you are struggling with project portfolio governance for portfolio management, contact us.

Tim is a project and portfolio management consultant with 15 years of experience working with the Fortune 500. He is an expert in maturity-based PPM and helps PMO Leaders build and improve their PMO to unlock more value for their company. He is one of the original PfMP’s (Portfolio Management Professionals) and a public speaker at business conferences and PMI events.

¹Weill, Peter; Jeanne W Ross. IT Governance. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2004. ²Datz, Todd. “ Portfolio Management: How to Do It Right .” CIO.com. Ed. Todd Datz. May 1, 2003. April 26, 2019. ³Lencioni, Patrick. The Advantage. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2012.

What is portfolio governance.

Project portfolio governance refers to the governance of all projects in the portfolio. Good portfolio governance is about having the right people making good strategic decisions with the right information at the right time. Strong portfolio governance forms the foundation of project portfolio management and is involved in all four components of the portfolio management lifecycle.

Why is portfolio governance important?

Project portfolio governance involves strategic decision making. According to Peter Weill and Jeanne W Ross, effective IT governance is the single most important predictor of the value an organization generates from IT. In fact, it has also been said that portfolio management without governance is an empty concept (Datz). Hence, a well-defined and properly structured governance is critical to manage the portfolio.

What are portfolio governance success factors?

1) Active engagement – coming prepared, being present, asking questions, proposing solutions 2) Open, honest, transparent discussions – working comfortably through conflict to find the best possible answer 3) Ability to make tough trade-off decisions – preventing misaligned projects from draining critical resources 4) Shifting from a singular project view to an aggregate portfolio view – always asking ‘how will this impact our portfolio?’ 5) Focus on optimizing portfolio value – finding the right combination of projects that unlock greater portfolio value 6) Balancing long-term and short-term needs – not always choosing the easy projects 7) Communicating a consistent message – reinforcing business goals and objectives; demonstrating this through results

Never miss an Acuity PPM article

Don't take our word, listen to what others are saying: "I find value in all of your articles." "Your articles are interesting and I am sharing them with my team who have limited project knowledge. They are very useful."

We use cookies from third party services to offer you a better experience. Read about how we use cookies and how you can control them by clicking "Privacy Preferences".

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

When you visit any website, it may store or retrieve information through your browser, usually in the form of cookies. Since we respect your right to privacy, you can choose not to permit data collection from certain types of services. However, not allowing these services may impact your experience and what we are able to offer you.

Privacy Policy

Crafting An Effective Project Portfolio Management Governance - A Guide For PMOs

In this article, we provide you with a standard definition, recommendations and best practice approaches on how to establish a meaningful governance that is in line with your strategic objectives.

Would you like to deepen your knowledge of project portfolio management?

The article "Project Portfolio Management - An Introduction For Practitioners With Little Time On Their Hands" is waiting for you with detailed information and analyses

Understanding the Essence of Governance

In the intricate tapestry of project portfolio management, a well-crafted governance is the cornerstone of success. For Project Management Office (PMO) members, creating a governance framework that seamlessly aligns with organizational objectives is both an art and a strategic imperative. This article unveils key insights and recommendations to guide PMO members in the artful creation of a governance framework that resonates with and propels strategic organizational goals.

Why have a Governance Framework at all? And who is responsible for creating it?

Governance in project portfolio management refers to the set of policies, procedures, and decision-making processes that dictate how projects - and the entire portfolio - are managed within an organization. It serves as the compass that ensures projects align with overarching organizational objectives, values, and standards. The latter is a key part of governance manuals - and for quite a simple reason: only if you follow some set of standards, you can compare projects against each other sensefully. That in turn, is the prerequisite of a purposeful aggregation of projects to a portfolio.

As custodians of project portfolio management excellence, PMO members are uniquely positioned to influence and shape the governance framework. However, project variance is vast. Finding a one-size-fits-all governance framework is hence rather challenging for the entire team. Check out what you probably should consider standardizing in the next section.

Key Components of an Effective Governance

A well-crafted governance comprises what you and your organization need to set as standards, to keep your project portfolio aligned and transparent. This may be different for each organization and its respective company culture, depending on the composition of the team. Yet there are a few things that most frameworks have in common.

Establish Strategic Fit

A governance should seamlessly align the project portfolio with the broader organizational strategy. PMO members must actively participate in strategic planning sessions, ensuring that project initiatives directly contribute to and reinforce the organization's objectives. A rather easy way to make sure this happens is to require projects contributing to at least one of the strategic goals.

Define Roles and Responsibilities within the team

Establishing clear roles and responsibilities is the foundation of effective governance. Define the duties of project managers, team members, sponsors, and other stakeholders. This clarity ensures accountability and sets the stage for streamlined decision-making. Make sure your own role - i.e. PMO tasks and responsibilities - are clear, too.

Define The Level Of Detail You Expect

Establishing the level of detail you require - especially when it comes to milestone planning - is paramount. Other than commonly believed, is often not more detail that is sensible, it is less.

Define A Stage Gate Process

This is a pretty broad topic in project portfolio management. But projects are usually in different phases during their lifecycle (e.g. from the idea to the realization phase). Make sure you select a suitable process that fits your needs.

Define A Risk Escalation Channel & Process

What happens if a project does not unfold as intended, and how is this information communicated and, if necessary or if certain risks occur, escalated? Everyone should know the proper channels at all times.

Define A Robust Reporting Cycle

The project cycle helps in establishing a successful routine for project portfolio work and will immediately increase the team's performance. There is hardly anything more important than the quasi-religious pursuit of this cycle. Only with this regularity can the project be well accompanied by the PMO, and issues can be addressed in a timely manner. Experience shows that without a strict cycle, transformations are almost always doomed to failure because they fall asleep. So make sure to choose a cycle and format (e.g. a monthly steering committee with C-Level involvement, PMO, and all project sponsors) that fits your needs. Find more on this very important step here .

Define A Robust Decision-Making Process for your PPM

Crafting a governance framework involves designing robust decision-making processes. Clearly outline how decisions will be made, who the decision-makers are, and the criteria guiding those decisions. This clarity minimizes ambiguity and accelerates the decision-making process.

Tailoring the Governance to Organizational Culture

Embracing organizational culture.

Successful governance is rooted in an understanding of and alignment with the organization's culture. PMO members should tailor the governance to complement the existing cultural fabric, ensuring that it is embraced rather than resisted by the organization.

Communication Strategies

Effective communication is the lifeblood of governance. Establish transparent communication channels to disseminate governance policies, updates, and changes. Open dialogue fosters understanding and buy-in from all stakeholders, promoting a collaborative governance culture. A commonly used point in time to communicate the governance effectively is kick-off meetings. The kick-off is an art in itself - and we happen to have a little free-of-charge resource for you up our sleeves. Check for yourself!

Balancing Flexibility and Control

Adaptable governance structures.

The best governance structures strike a balance between providing structure and allowing flexibility for different processes. PMO members should design governance structures that are adaptable to changes in project portfolio landscapes while maintaining sufficient controls to mitigate risks.

Continuous Monitoring and Improvement

Governance is a dynamic process that requires continuous monitoring and improvement. Implement mechanisms for regular assessments and reviews of the governance. Use feedback loops to identify areas for enhancement and ensure ongoing alignment with organizational objectives and the overall strategy.

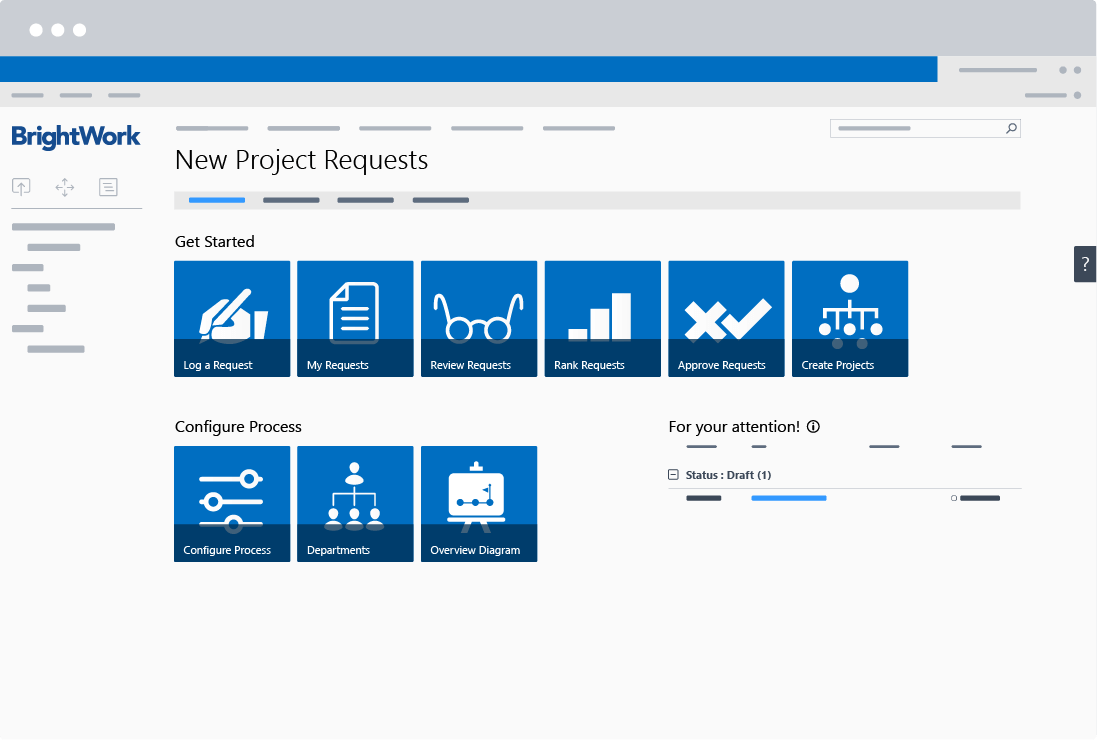

Leveraging Technology for Governance Excellence

Implementing project portfolio management (ppm) tools.

Technology, specifically Project Portfolio Management (PPM) tools, can significantly enhance governance efficiency and consequently the performance of your project portfolio. These tools provide a centralized platform for documenting, tracking, and managing projects. Automation streamlines workflows improves reporting accuracy, and facilitates real-time decision-making, even in bigger teams.

Discover our PPM software Falcon!

At Nordantech, we develop a PPM software that is already used by leading companies and consultancies. We would be happy to tell you more about it in a personal meeting! Book a demo now

Data-Driven Insights

Leverage data-driven insights from PPM tools to inform governance decisions. Analyze performance metrics, resource utilization, and project outcomes to ensure that the governance remains adaptive and responsive to the evolving needs of the organization. Looking for more? Check out our interesting resource collection!

In Conclusion: A Roadmap to Governance Excellence

In the complex world of project management, the creation of a governance system is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. PMO members, equipped with strategic vision and a deep understanding of organizational objectives, can sculpt a governance framework that not only enforces rules but also fosters a culture of collaboration and innovation.

By embracing clearly defined roles, aligning the project portfolio with organizational strategy, and balancing flexibility with control, PMO members pave the way for governance excellence. In doing so, they not only navigate the complexities of project portfolio management with finesse but also contribute significantly to the overall success and resilience of the organization. As the architects of effective governance, PMO members hold the key to unlocking the full potential of every project in alignment with the grand tapestry of organizational objectives.

We would like to use cookies to improve the usability of our website.

- What is Portfolio Management?

- Portfolio Strategic Management

- Project Portfolio Management KPI

- Submit a Guest Post

How To Build Effective Project Management Best Practices?

Why You Need to Understand Project Management Basics ?

How to Make Change Management Bearable For Everyone ?

The Effective Way To Getting Better Lessons Learned

How To Determine If You Need To Build A Focus Group ?

Servant Leadership – It Works

Transformational Leader: How To Be One?

Going Above and Beyond with Human Resource Management

Things You Need To Know About Business Process Management

Some Things You Need to Understand About Employee Engagement

4 Ways You Can Bring Your Employees Together

The 15 Project Management KPIs: What They Do and Why You Need Them

The 20 Education Venues for Online Master of Project Management

Your Basic Guide to IT Project Governance Framework

The Road to Effective Project Management Governance

Portfolio governance management.

- Portfolio Performance Management

- Portfolio Communication Management

- Portfolio Risk Management

Select Page

Table of Contents

More and more companies these days are using the project portfolio management discipline to manage multiple projects in a competitive environment, with only access to finite resources. This contributes to limited success, which calls for the need to develop strategies to improve results. There is a better way to manage multiple projects despite the limited number of resources, and using portfolio governance management can pave the way to success.

But before any organizational strategic objectives are achieved, an organization must have a good understanding of governance as it applies to portfolios, projects and programs. The appropriate portfolio governance management plan is a factor in the success of portfolios and strategic initiative. So the lack thereof, would have the opposite result.

Given the dynamic organizational environment, with portfolio components constantly changing, implementing a framework of effective portfolio governance management can be challenging. There are also other factors in play, such as globalization, regulatory requirements, business complexity, and the rapid changes in business environments and technology. This underlines the importance of governance in PPM. One thing portfolio managers must remember is that portfolio, program, and project governance, must be a consistent approach.

What is portfolio governance management?

Portfolio governance management aims to answer the question how organizations should oversee portfolio management . It is a subset of the activities of corporate governance, and is mainly concerned of areas related to portfolio activities. An effective portfolio governance management ensures that a project portfolio is aligned to an organization’s objectives, is sustainable, and can be delivered efficiently.

It also ensures that a portfolio is defined, optimized and authorized in support of all decision-making activities done by the governance body.

Portfolio governance management will also serve as guide for investment analysis to:

- Identify threats and opportunities

- Assess change, impacts and dependencies

- Achieve performance targets

- Select, schedule and prioritize activities

In addition, portfolio governance management supports how project stakeholders exchange relevant and reliable information in a timely manner.

What are the processes of portfolio governance management?

What goes into the portfolio governance management process will depend on the industry where the PPM will be implemented. In the case of listed companies, for example, governance of portfolio management serves as a guide for board of directors to check their organization against the four main components of project governance management : portfolio direction, project sponsorship, project management capability, and disclosure and reporting.

For portfolio-based organizations, portfolio governance management follows four processes : developing a portfolio management plan, defining a portfolio, optimizing a portfolio, authorizing a portfolio and providing portfolio oversight.

Developing a portfolio management plan

In portfolio governance management, development of a management plan for a particular portfolio is an iterative process that involves a cycle of developing and updating a portfolio management plan. This ensures that the governance of a management plan is aligned with a portfolio’s charter authorization, strategic objectives and roadmap. Portfolio management plans also integrate subsidiary plans, such as those relating to communication, performance and risk management.

Defining a portfolio

The process of defining a portfolio within the context of portfolio governance management involves more than just identifying qualified portfolio component. It also includes key activities, such as categorizing components in a portfolio based on a common set of decision filters and criteria, and evaluating those components using ranking and scoring model.

Through these activities, an updated list of qualified portfolio components will be created, which is necessary in producing an organized portfolio for use in an ongoing process of evaluation, selection and prioritization. This part of the portfolio governance management process will ensure that resources will be allocated to components that provide the most significant value or return of investment, and are strongly aligned with organizational objectives and strategies.

Optimizing a portfolio

Portfolio optimization is vital to portfolio governance management, because it ensures a portfolio is optimized and balanced for value delivery and better performance. Optimization involves key activities performed on portfolio components. These include:

- Evaluate portfolio components

- Perform risk analysis

- Evaluate and determine performance

- Evaluate benefits and expected value

- Determine resource capability, capacity and constraints

- Determine the highest priority portfolio component

- Balance or rebalance activities, depending if their components that need to be re-prioritized, suspended or terminated

Portfolio optimization in portfolio governance management also includes evaluation of trade-offs to ensure portfolio success. How can managers strike a balance between risk and return, or between short-term and long-term goals? If resources are limited, it is also balanced across the platform to ensure strategic priorities.

Other balancing activities involve reviewing portfolio components that have been selected and prioritized. Using several factors, such as desired risk profile, predefined portfolio management criteria, performance metrics, and capacity constraints, a portfolio is balanced to ensure that it supports organizational objectives and strategies.

Authorizing a portfolio

In portfolio governance management, the purpose of authorizing a portfolio is to activate or execute portfolio components through resource allocation. Once a selected portfolio component is authorized, allocation of resources follows. Funding and resources for portfolio components may come from those allocated on deactivated and terminated components.

Part of the process of portfolio authorization is to communicate changes in the portfolio and other related decisions to interested parties, stakeholders, governing bodies, and portfolio, program and project managers.

Providing portfolio oversight

Because the purpose of portfolio governance management is to ensure that portfolio components align with an organization’s strategy and objectives, any oversight must be avoided. Providing portfolio oversight is also geared to making governance decisions in response to performance of a portfolio, proposals and changes of portfolio components, resource capability and capacity, requirements for future investments and funding allocations, and risks and issues.

To provide portfolio oversight, there are key activities involved, which include review about portfolio resources, performance, risks and finance informations; compliance with organizational standards; communicate governance decisions, and reporting of any changes in the portfolio, as well as information on performance, risks, resources and finances.

Project Portfolio Governance

Project portfolio governance is used to identify, select, monitor and prioritize projects within an organization or a line of business. It is often guided by the foundation of the processes previously mentioned. And when the foundation is firm, ongoing portfolio governance management and oversight will reach their strategic destination, or help project portfolio managers to navigate to the reach the same end.

For a portfolio management strategy to succeed, it must have end-to-end framework that will guide organizations throughout the portfolio management process, from selection to execution. Governance is a framework, where decisions on project/program are made. Together, they create a portfolio governance management plan that can cater to a culture in which they are delivered. It has to be well structured as well so it can provide value to PPM.

An effective portfolio governance management results in:

- Accountability of everyone involved, and where clear responsibilities, roles and accountabilities are established.

- Transparency on what the scope is, and who are the stakeholders and financial authorities. This can be achieved with regular meetings.

- Integrity in implementing portfolio governance management, observing ethics and etiquette.

- Protection of concerned parties against disputes, providing conflict resolution as needed, and empowering individuals to do the right thing.

- Compliance to the standards of portfolio governance management, including a clear procurement process, and adherence to legal, regulatory and policy requirements.

- Availability of data provided by clear reporting and unobstructed information flow.

- Flexibility in a dynamic environment, demonstrating the ability to adapt to changing needs at a business and organizational level, and the ability to accommodate any shift in the size and complexity of an organization.

- Retention where applicable, and a clear transition from project or program to operations.

Strategy and guiding principles of portfolio governance management

Before any organization decides to pursue a project, it must first consider numerous factors and compare it against a proposal. Additional variables under strategy, finance, risk , and technology must be taken into account as well. These 4 disciplines will provide insights to the following:

- The benefits and value that will arise from a project. Identify the reasons why your undertaking the project in the first place, and make sure not to overlook business value vs. spend ratio.

- Feasibility or likelihood of a project to be successful. Are the risks worth taking? Is a project simple and easy, but yields great benefits?

- Clarity and availability of solutions, particularly those that align with the current strategic goals, technology roadmap, and organizational culture.

- Positive impact on the stakeholders. This refers to the material impact on customers, and whether or not a project is perceived as high-performing or high quality.

Without losing sight of the requirements of an organization and its strategic goals, the most viable option is then selected.

Structured processes and methodology in portfolio governance management

A methodology refers to the set of rules used in a specific discipline or study. It doesn’t provide a solution, but a guide or a list of best practices to achieve goals, or to come up with a solution. A methodology also allows flexibility in managing efforts to reach a particular objective.

Used in portfolio governance management, a methodology will serve as rules for governance, which will lay out the framework necessary to achieve organizational strategic objective.

- Portfolio ownership and accountability

- Define the committee structure that will steer portfolio governance management in the right direction

- Determine roles and responsibilities that will be assigned to stakeholders and other players. It seeks to answer the question of who will authorize, amend, continue or stop a project, and decide who will control the overall investment budget, and set the standards for project and portfolio management.

Communication and coordination model

One of the reasons that a portfolio underperforms is the lack of effective tools and processes accessible to the team that must provide input, and to the sponsors that must obtain the output. Failure to oversee and manage a portfolio properly translates to failure of portfolio governance management.

Apart from effective tools and processes, coordination also matters. Governance and oversight must be paired with leadership to develop a well-crafted portfolio governance management plan. The best example of this is a PMO aligned with the organization strategy to ensure better management over multiple projects. Without coordination on all aspects, portfolio management could be no management at all.

Communication is also vital to portfolio governance management. It should be grounded in transparency, reliability and fairness, and must be in support of the stakeholders and the organizational strategy. In portfolio governance management, transparent and reliable communication is crucial in escalating and resolving issues, and in mitigating risks more efficiently and timely.

This underlines the importance of proper communication and escalation process in portfolio governance management. The rules must be easy to follow, with stakeholders fully aware of their existence and in complete agreement to follow them.

A good example of a clear and understandable mechanism of escalating issues and concerns must specify the following:

- Stakeholders responsible for making decisions and defining the escalation path.

- Escalation path must be unique to the type of risk and issue at hand.

- Tools, processes and the people necessary to resolve escalated issues must be identified and held accountable.

- Predictability and repeatability should be part of the escalation process, with time frames and proper resolution communications specified.

- Feedback mechanism that support and sustain governance in portfolio management, and organizational operation, competitiveness and regulatory needs.

Portfolio performance and diversification

Portfolio managers must be aware of how governance and financial discipline can improve the performance of a portfolio by asking relevant questions. In most cases, better portfolio management is an outcome of several solutions, including improved performance, lower cost, reduced risk and higher ROI.

Risk should be included as a component of portfolio governance management, simply because there is no such thing as a risk-free portfolio. In fact, an organization must identify its risk tolerance to be able to achieve a tolerable overall risk level, as a means to improve portfolio performance and pave way for diversification. As long as there is a framework for minimizing risk impact, adding risks in portfolio governance management can prove beneficial.

To diversify a portfolio, managers must use governance to better select and prioritize components. They should consider if a portfolio is adequately diversified, and then add other components to achieve the right amount of diversification. They must also take into account taxonomy of project types, risk profiles and ROI.

Recent Posts

Join Our Community !!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Advertisement.

- Communication Management

- Portfolio Management

- Program Management

- Project Management

- Project Management Best Practices

- Project Management Methodology

- Project Management Office

- Project Management Techniques

- Strategic Planning

PPM Express

Integrated Project Portfolio Management

Portfolio Governance, Ensuring Alignment to Strategy, in a PMI way

What is portfolio governance.

As per Project Management Institute (PMI) , Portfolio Governance is termed as the framework, functions, and processes that guide portfolio management activities to optimize investments and meet organizational strategic and operational goals. These activities determine the actual versus planned aggregate portfolio value ensure that portfolio components (sub-portfolios, programs, projects, and operations) deliver maximum return on investment with an acceptable level of risk.

Generally, portfolio governance ensures the correct strategic alignment of components to achieve organizational strategy . It is responsible for decisions regarding resources (e.g., human, financial, material, equipment), and ensures alignment to the investment decisions and priorities while any significant organizational constraints are being considered. Portfolio governance provides the framework for making decisions, providing oversight, ensuring controls, and overseeing integration within the portfolio components.

Usually, portfolio governance decisions are made at different levels of the organization based on the established portfolio authority system. They support specific strategies, goals, and objectives as defined by the strategic planning process. Governance guidance, decision making, and processes may cross-organizational and functional management areas of an organization.

In this way, portfolio governance guidance and oversight may be issued from organizational governance and multiple governing bodies. These governing bodies must be connected to ensure effectiveness and align each decision with the established organizational strategy. Portfolio governance should involve the least authority structure possible as time and costs are associated with governance activities.

The below diagram provides an example of a Portfolio Governance structure depicting how a portfolio governing body provides governance and oversight to the portfolio components teams.

Decisions made at the Portfolio Governing body level may impact the portfolio’s current and future projects and programs. Such impacts include terminating, canceling, or reprioritizing programs or projects within the portfolio . The governing body ensures that the decisions, portfolio goals, and investment mix are aligned with organizational strategies. Issues and risks regarding the portfolio performance are escalated to the governing body for required decisions.

The governance coordinates, when applicable, reporting on portfolio performance and decision-making to corporate and portfolio management offices. Portfolio governance processes and activities enable portfolio performance evaluation and provide resourcing and prioritization decisions when needed. The portfolio manager or portfolio management team makes recommendations to the governing body for decisions and guidance.

These recommendations may include adding new components, programs, and projects, and suspending or changing existing features. The portfolio governance coordinates portfolio performance reporting and decision-making to organizational governing bodies and portfolio management offices.

Portfolio Governance Considerations

Governance occurs at various levels of the organization to support the organizational goals, objectives, and strategies. The portfolio governing body reviews the portfolio’s actual versus targeted performance to reach key decisions. This ensures that the portfolio continues to be on track to manage the portfolio risks and deliver business value and benefits to achieve the organization’s strategic objectives.

As strategic organizational changes occur, governance assesses the impact on the portfolio and determines what adjustments are needed in portfolio goals, plans, and component mix. The organization provides the decision-making mechanism to respond to the proposed strategic changes.

As strategic changes are being made, continuous strategic alignment may impact the planned and delivered benefits. Portfolio governance activities monitor portfolio risks that may affect the financial value of the portfolio.

The portfolio component mix is used to achieve the organizational strategy and objectives that impact the organization’s capacities and capabilities.

Another portfolio governance consideration is the integrated governance processes. This critical component of the governance activities includes strategic alignment, prioritization, authorization of components, and allocation of internal resources to accomplish organizational strategy and objectives.

Portfolio Governance Roles and Responsibilities

As per the Standard of Portfolio Management 4th edition , the key roles for portfolio governance are the following:

- Portfolio Governing Body;

- Portfolio Sponsor;

- Portfolio Manager ;

- Portfolio, Program ,

- Project management Office (PMO);

- Program Sponsor;

- Program Manager ;

- Project Sponsor;

- Project Manager ;

- Functional Managers.

There may be additional roles, depending on the organizational structure.

Portfolio Governing Body: The portfolio governing body is a collaborative group of executives representing various portfolio components and operational work to support the portfolio by guiding the governance functions. The purpose of the governing body is to authorize and prioritize portfolio work. The governing body ensures that the portfolio is aligned with the organization’s strategy by providing the appropriate oversight, leadership, and decision-making.

Portfolio Sponsor: A sponsor is a person or group who provides resources and support for the project, program, or portfolio and is accountable for enabling success. Sponsors champion the approval of portfolio components (projects, programs, and operations). Once the portfolio component is approved, the sponsor helps to ensure that the components perform according to organizational strategy and objectives. Sponsors also recommend portfolio component changes or closures to align with corporate strategic changes.

Portfolio Manager: The Portfolio manager’s role is to interface with the governing body and manage the portfolio to ensure that the programs, projects, and operational components deliver the intended benefits and meet the organization’s strategic objectives.

Program Managers: The Program manager’s role is to interface with the portfolio manager, governing bodies, and program sponsors and manage the program to ensure the delivery of the intended benefits.

Project Managers: The Project manager’s role is to ensure project conformance to governance policies and processes on the one hand. And to interface with the portfolio manager, program manager, and project sponsor to manage the delivery of the project’s product , service, or result on the other hand.

Portfolio Management Office (PMO): The role of the PMO may vary depending upon the needs of the organization. The portfolio may have its PMO, or a PMO may support several portfolios.

Other Key Stakeholders : Other key stakeholders’ roles are to support portfolio organizational and process changes.

Portfolio Governance Functional Domains and Processes

The related portfolio governance functions and processes are grouped into four domains:

- governance alignment ,

- governance risk ,

- governance performance ,

- governance communications .

Processes, activities, and tasks are categorized by the functions of oversight , control , integration , and decision making . These processes are not role-specific and pertain to all activities in the governance domains.

The generally recognized processes for portfolio governance are categorized by domains and processes, as summarized in the table below. The term “generally recognized processes” does not mean that the processes would be applied uniformly to all portfolios. Instead, the organization’s leadership is responsible for determining what is appropriate for any given portfolio.

Concluding Remarks

Portfolio governance is a bridge between organizational governance, program and project governance, and operations. Governance levels are linked together to ensure that each governance action is ultimately aligned with the defined corporate strategy. It is crucial to assess the current executive and portfolio governance that may exist for a given portfolio.

The primitive step is to determine the contemporary governance applicable to the portfolio to be applied:

- determine the business need, benefits, and justification;

- define the portfolio’s governance authority structure and membership.

If there are no governance practices, the portfolio manager or sponsor should establish them during portfolio definition. This is when the strategic portfolio plan and charter are created.

We value your privacy

Privacy overview.

Project Governance: How Little Processes Can Have Big Impacts

By Andy Marker | January 23, 2018 (updated October 12, 2021)

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

Whether big or small, your projects are important merely for the fact that you spend money and time on them. However, we know that the majority of projects fail, even with stellar project managers and a dedicated staff in place. Project governance, though not well understood, can stack the deck so that projects have a better rate of success. Project governance imposes processes that have a big impact — even when the processes seem small and inconsequential.

Project governance is not your corporate governance, and your business should not run it as such. In this guide, you’ll learn about project governance, how its components relate to the real world, the definition of a governance framework, the difference between governing and managing, and best practices from experts in the field.

What Is Project Governance?

Developed from the larger concept of corporate governance , project governance is the structured system of rules and processes that you use to administer projects. It provides a company with a decision-making framework to ensure accountability and alignment between the project team, executives, and the rest of your company. You can also apply project governance to your portfolio to govern your programs. Project governance differs from daily governance, also known as your organizational governance , since daily organizational rules and procedures cannot provide the structure necessary to successfully deliver a project. This concept is the difference between “business as usual” and “changing your business.”

Further, projects have stakeholders spread throughout an organization. Project governance should help you accomplish projects on time and on budget by bringing together these stakeholders for efficient decision-making. Project governance should also help you choose the right projects by providing the relevant structure, people, and information. The main focus should be on those key decisions that not only shape the project, but the project direction.

Since projects bring in necessary revenue for many industries, their failure or lateness can mean the difference between a company’s failure and success. It is a well-known fact in the project management industry that a high rate of projects fail. According to a 2016 study by PwC, almost 45 percent of capital projects are delayed by six or more months. Of these delayed projects, only eight percent were due to technical reasons, while the remaining 92 percent were late due to management deficiencies. This points to a lack of project governance, with deficiencies in organization, resources, oversight, planning, or unclear goals. The same applies to software projects. The 2016 Standish Group Chaos Report listed 71 percent of software project as failures.

Do not confuse good project management with good project governance, however. Many of the setbacks in a company’s projects are outside the purview of the project manager, but do lie in governance. The distinction between management and governance is in focus and intent, and it is considerable. According to the Project Management Institute (PMI), project management is all about the details. The site defines project management as “the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities to meet the project requirements.” Project governance is about less about the details, and more about the conditions that set up the project and are outside the project’s boundaries. A project manager completes projects within their organization’s framework established by the governing body, (the board). This governance details the project’s needed guidance, oversight, and decision-making.

In the fields of information technology (IT) and data analytics, governance of projects is similar, but has some added elements. The projects you choose should be the right project for your company, and you should be able to support that decision. You can hire the most successful project managers available, but they will not succeed if the company does not have the right conditions in place. For IT projects, this includes IT-specific processes, such as data governance and policy review and approval. For data projects, conditions include data-specific issues such as data ownership questions, data inconsistencies, and how to use big data.

Some companies, especially large ones, have a project management office (PMO) that can support good governance by ensuring its formalization. In some smaller companies, some of the governance functions may actually come from the behest of the project manager. Although this is not ideal, there are ways to ensure that roles and responsibilities are clear and appropriate.

What Is the Governance Structure?

The governance structure is the power structure your company puts in place. Companies develop their governance structures in a multitude of ways to suit their business. Many have a tiered approach that can provide adequate accountability. Many companies also have different committees with defined roles and responsibilities. Further, some combine or share roles as per the project’s needs. Here are some of these roles in project governance:

- The Project Sponsor: Also known as the project executive , this position is responsible for providing cultural leadership, developing the business case, keeping the project aligned with the company’s strategic objectives, and directing the project manager. Stakeholders may also look to the project sponsor as a source of information.

- The Project Board: Also known as a steering committee , you charge the board with developing the project charter and ensuring that it is in compliance with the business case. The charter should provide direction for decisions that are elevated to them from the project manager, as well as approval of the overall project budget. You should set up your project board at the beginning of your project life cycle and they should operate until the project closes. All of the board members should have some stake in the project. Remember, this board is not the same as your company’s board — it only oversees a particular project. Your chair should be the most senior person responsible for the project, and include members that have a stake in the project’s outcome, such as people who can represent both the project’s users and the project’s suppliers.

- The Project Manager: This person is responsible for managing the project. The project manager performs all of the planning, initiation, execution, monitoring, and closing of a project within the confines of the business case. The person in this role should be detail-oriented and able to control the risk and accomplish the project. Project managers make many decisions, until the decision necessary violates the agreed upon business case. At that point, the project manager must elevate the decision to the board.

- The Project Stakeholders: These are the entities, whether individuals or companies (internal or external), who have an interest in or an influence on a specific project. Their influence can be positive or negative to your project outcomes, so your project manager should identify them at the outset of the project.

- The Project Management Office (PMO): Many large companies have a PMO, which provides a variety of functions within an organization. In project-based companies, the PMO supports the management much closer than in companies that have less frequent projects. Some PMOs are developed for a specific project, while others exist for multiple projects and provide support in a variety of ways.

Elizabeth Harrin, Author of four project management books and Blogger at GirlsGuideToPM.com , sees the PMO as a useful entity within an organization. “As a project manager, if you feel you need a bit of support, you can ask a colleague with more experience or someone in the PMO to review your project. They'll look for how you are managing the work and whether you are following company processes. For example, they might check to see if you are doing adequate project reporting and whether the reports actually reflect reality,” she advises.

- Senior User: This manager is responsible for the final user’s requirements and the interests of those users who will benefit from projects, especially software projects. For example, your product manager may be a good choice as your senior user, since they will be your company’s champion of the final product.

- Senior Supplier: A manager who is responsible for the product quality and the interests of the suppliers.

What is consistent across project governance is that there is no consistency. There is no one approach, mainly because it needs to be tailored to the specific company’s needs. The most important structural elements in project governance:

- It aligns with your organization’s current governance.

- It has longevity.

- It can monitor and control your project effectively.

What Is a Project Governance Framework?

It’s ideal to create a governance framework in which your projects can easily move forward and be fluid. The last thing you want is for a project to be in limbo due to bureaucracy or unnecessary scrutiny. Your governance framework should provide enough visibility and oversight so that the project board understands and manages risks quickly.

Jon McGlothian, Principle and Cofounder of The Mt. Olivet Group , has over 30 years leading and directing various sizes and types of projects. In his experience, he believes it’s best to establish the framework at the beginning of the project. “Project governance is the framework for how we administer the project activities and achieve our project goals,” he says. “The size, nature, and complexity of the project as well as the cultural norms of the entity will determine how robust the framework will need to be.”

Managing projects can be a challenge — that’s why it’s imperative to have a framework at the outset. “Remember, every project and organization is different, so there is not a one-size solution that fits all situations. However, key areas that you should address are risk management and change management . This does not imply that other areas are not important,” says McGlothian. “It is just that if you have a framework for how you deal with the various risks that may arise on the project, you will develop and implement a great plan. Likewise, all projects will change during implementation. The changes will involve different stakeholders. How the project team will work with different constituents throughout the project will determine how successful the project will be. Finally, it is important to understand the ‘rules of the road’ for doing a project within the organization. This includes both the written rules as well as the unwritten rules.”

The framework should encompass structure, people, and information — but it should be the right ones, irrespective of corporate governance. Follow the steps below to develop a governance process for your next project:

Step 1: Appoint One Person Accountable for Your Project’s Success. Assign one person who is a constant over the life of the project. This person is not the project manager, however. They should be from the business unit that the project benefits. You can identify them as either the project owner or project executive.

Step 2: Ensure Your Project Owner Is Independent of the Asset Owner. The goal of a project is to deliver a business outcome. Asset owners are not an appropriate choice to own the project because they not only have different skill sets, but they have bias. The project owner should represent the business unit that will benefit from the project, but also have enough distance to remain unbiased. A desirable choice is the service outcome owner.

Step 3: Develop a Project Board. The project owner needs the support of key stakeholders. These people could be the funders, users of the project’s end-product, and internal or external project suppliers. Aim to have no more than six members on the board (including the project owner) to keep the decision-making efficient. This board should manage by exception, in that they only become involved when the business case parameters are threatened, and decisions must be made.

Step 4: Ensure Separation of Stakeholder Management and Project Decision Makers. Managing your stakeholders is always a possibility. However, do not assign stakeholders as decision makers unless they are part of the board. If you have many stakeholders that want a voice, you may want to form an advisory group and have the project owner chair the group to give it legitimacy.

Step 5: Ensure Separation of Corporate Governance and Project Governance. The project board should not have to report to the same entities as the corporate board, or to someone higher in the company. They should be able to make key project decisions that stand.

Step 6: Empower Your Project Owner. The project owner should be involved and able to make project-related decisions. They must also own the business case (the justification for their project and its benefits).

Step 7: Develop and Maintain the Business Case. Your business case should justify the investment and be the key governance document for the project board. Be sure to well-document the change history, and that the board assesses any changes from the original project intent. The business case should include project drivers, intended outcomes, expected benefits, the scope, the funding source, any assumptions, any interdependencies, and the schedule.

Step 8: Ensure Decision-Making Responsibilities Are Clear. There may be many stakeholders involved, so it is critical that everyone involved in the project is keenly aware of their responsibilities. There should be no overlaps or gaps. For example, your project board approves the business case and anything that potentially changes the business case. Your project manager makes daily decisions, if they do not affect the business case. If the board and other parties own a project, create a formal agreement on the decision-making process and governance before the project kickoff, as well as a dispute resolution process.

Step 9: Documentation. The title of this step says it all. Document everything related to governance. Be sure to include policies on project governance that define your risk-based approach, the decision rights of all parties, roles and responsibilities, and any terms.

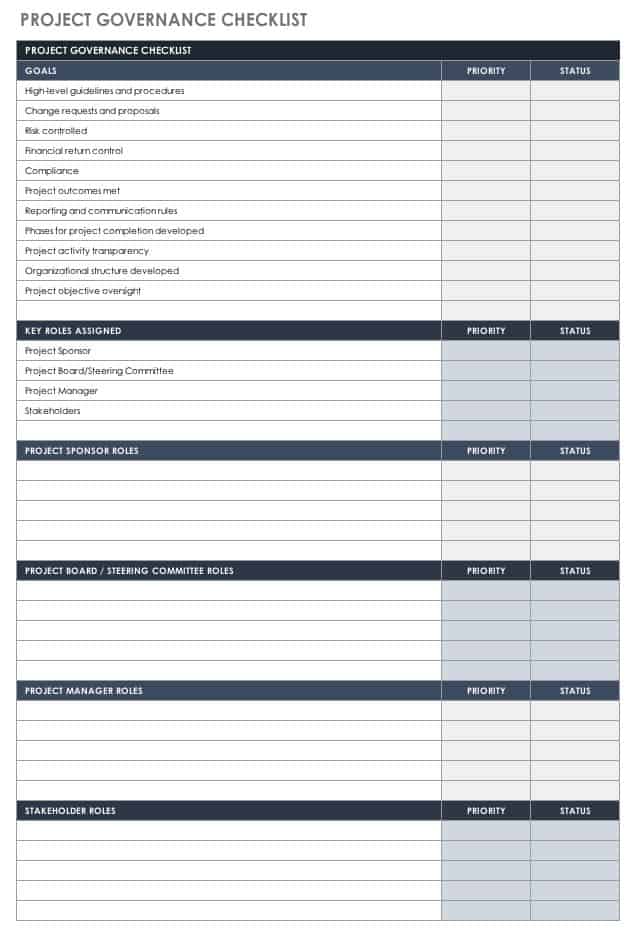

Use this free Excel checklist for writing your own project governance plan.

Download Project Governance Plan Checklist - Excel

How Do Governance Components Relate to The Real World?

All of the information on project governance is fine in theory, but reality is often messy, complicated, and does not allow for a one-size-fits-all approach. The following are components found in project governance and how they actually relate to the real world:

- Governance Models: Try to strike a balance when developing a governance model. The project manager (who develops this model) should aim for enough rigor to engage the stakeholders, but not so much that it is restrictive. The project scope, timeline, risks, and complexity should help the project manager create this balance.

- Accountability and Responsibilities: The project manager defines the accountability and responsibilities of the people involved in the project. Without these defined, your plan is less effective. Your meetings will be less valuable because the group will always be hashing it out, and your risk assessment and change control process will not work.

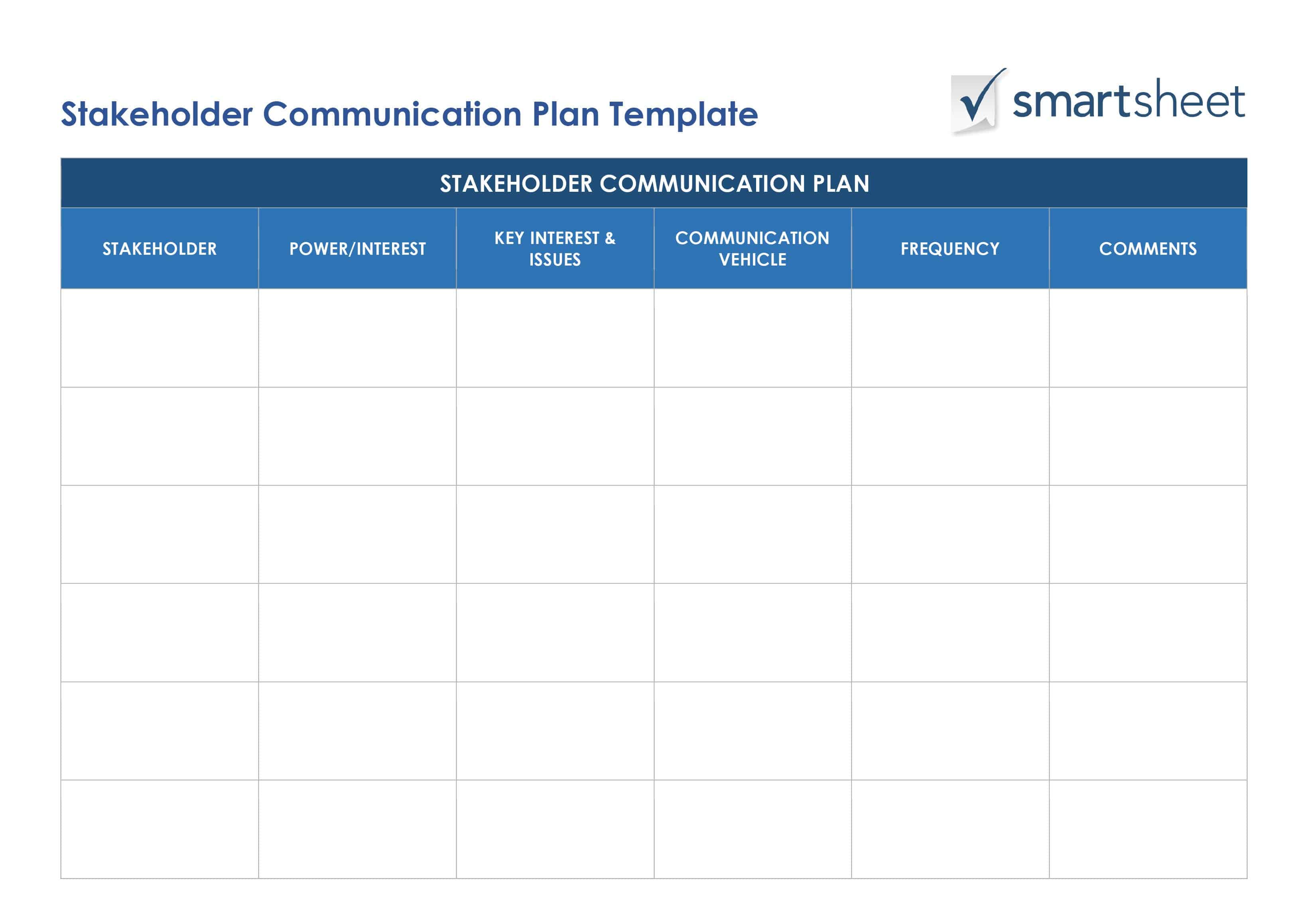

- Stakeholder Engagement: Although it seems like an exercise in futility, identifying all the stakeholders is actually a critical part of the process for understanding your project’s environment. Stakeholders can affect a project positively and negatively. If you leave out an important stakeholder, their influence can disrupt the project. Once you determine the stakeholders, the project manager will develop a communication plan .

- Stakeholder Communication: After identifying stakeholders, develop a communications plan that focuses on getting the right information to the right people in a timely way. A communication plan details how and in what way you will share necessary messages to ensure stakeholders view your project as transparent and specific.

Stakeholder Communication Plan Template - WORD

- Meeting and Reporting: This component involves striking a balance between reporting and having meetings. The information the project manager releases should ensure that all stakeholders know when and how to expect updates. They will want to know when and how they can ask questions, and how they will know the project is on track.

- Risk and Issue Management: Before a project kicks off, a real-world project manager will settle a consensus on how recognize, classify, rank, and possibly handle risks and problems. Every project has problems; preparation can help save some time and heartburn along the way. For more information on risk management, read “ Project Risk Management: Best Practices, Tips, and Expert Advice .”

- Assurance: The easiest way to assure stakeholders is to provide evidence that the project is on time and on budget by sharing metrics and performance measures. It seems like a simple component, but in reality it is quite complex. The metrics provide the checks and balances in black and white. The metrics reveal any deviations and should also be delineated at the start of the project to set a baseline.

For new project managers, Jonathan Zacks, CoFounder of GoReminders , advises, “Come up with a way to measure the value of initiatives. Use that in conjunction with qualitative data, rather than relying solely on it, when making decisions on what to do and not do. A couple of examples:

- Put exact dollar values on projects and tasks when deciding which to prioritize. That will allow you to weigh the tradeoffs between competing initiatives.

- Come up with a formula for deciding priority. For example, we use a formula for planning which features to add to our appointment reminder app. It's adapted from a spreadsheet that Baremetrics founder Josh Pigford shared that calculates "scores" based on Status, Demand, Impact, and Effort. Here's the template, called Feature Framework .

Keep in mind that it's often easy to nudge the numbers to support preconceived ideas, so be careful. Most importantly, use your best judgment after looking at quantitative and qualitative data.”

- Project Management Control Process: In the real world, this is a constant, ongoing process that leads to action in the case of deviations.

What Is Governance Framework?

Governance framework, also called governance structure , is the relationships, influences, and factors that define how you use the resources in your organization. Whether you work for a government agency or a small business, the governance framework decides how the power is wielded and managed. Good governance provides accountability. As such, a process to make the best possible decisions participates in good governance. A company can demonstrate good governance in many other ways, including the following:

- Documenting and communicating the decisions made at approval gates

- Using a lifecycle governance plan

- Ensuring the roles and responsibilities within the company structure are delineated clearly

- Showing alignment between governance and the strategic plan

- Providing oversight and adherence

- Adhering to the business case and making transparent decisions upon deviation

When two or more organizations are involved in a venture or project, good governance looks like formal agreements. All organizations should agree on these arrangements prior to their working relationship or project kickoff, and they should have the ability to re-evaluate their relationships regularly via approval gates. Other key topics in good governance include the following:

- P3 Management: These are the methods that manage projects, programs, and portfolios.

- Knowledge Management: This is how the information and data are handled in a company. Learn more about this topic by reading “ Knowledge Management 101: Knowledge Management Cycle, Processes, Strategies, and Best Practices.”

- Life Cycle: This is your plan to manage your business information or project from beginning to end.

- Maturity: This is the increase of capacity or capability in a business.

- Sponsorship: This is what links corporate governance, a strategic plan, and P3 management.

- Support: Support refers to the environment for your governance managers that helps them accomplish consistency and success.

Airto Zamorano, Founder and CEO of Numana SEO and Numana Medical , says, “I believe there is a process that can be followed, or at least used as a governance framework to be modified to fit a unique set of needs. It is as follows:

- Create a detailed structure for the project from the beginning.

- Tie in company values, priorities, and objectives to work in conjunction with the structure of the project.

- Choose a project leader, empower them, and leave them responsible for the success or failure of the project.

- Allow teams to operate autonomously as much as possible.

- Provide total clarity on decision making responsibilities within the team from the start, and adhere to it throughout the project.”