Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Coaching styles and sports motivation in athletes with and without Intellectual Impairments

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft

Affiliation Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Department of Sport Exercise and Rehabilitation, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Kandianos Emmanouil Sakalidis,

- Florentina Johanna Hettinga,

- Fiona Chun Man Ling

- Published: December 22, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The cognitive limitations of athletes with Intellectual Impairments (II) may influence their sport behaviour and lead them to rely on coaches’ support. However, it is still unclear how II may influence sports performance progression and motivation and how coaches perceive their athletes with II and coach them. Thus, this study aims to examine 1) coach’s perceptions of motivation and performance progression in athletes with and without II, 2) coaching style (dis)similarities, and 3) the association between these factors. Coaches of athletes with ( n = 122) and without II ( n = 144) were recruited and completed three online questionnaires, analysed using a series of non-parametric analyses ( p ≤ .05). Results showed that perceived performance progression and controlled motivation were higher of athletes with II while perceived autonomous motivation was higher of athletes without II. No coaching style differences were found between the two groups. Additionally, a need-supportive coaching style negatively predicted amotivation, and a need-thwarting coaching style predicted lower autonomous motivation in athletes with II only. Overall, it seems that the coaches perceived that their athletes with II demonstrate different motivations and react dissimilarly to their coaching styles compared to athletes without II. They may also adopt different standards of sporting success for them. Due to these differences, it is important to offer appropriate training and knowledge to coaches about disability sports and the adaptations needed to effectively coach athletes with II. In summary, this paper gives some insights about the coach-athlete relationship and highlights the necessity to further support the sports development of people with II.

Citation: Sakalidis KE, Hettinga FJ, Ling FCM (2023) Coaching styles and sports motivation in athletes with and without Intellectual Impairments. PLoS ONE 18(12): e0296164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164

Editor: Ali B. Mahmoud, St John’s University, UNITED STATES

Received: December 20, 2022; Accepted: December 7, 2023; Published: December 22, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Sakalidis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: We will store data in the University repository: https://library.northumbria.ac.uk/research-data-management/figshare This is the doi: https://doi.org/10.25398/rd.northumbria.23284472.v1 .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

According to the convention of the rights of individuals with disabilities, people with Intellectual Impairments (II) have the right to participate in the sports activity of their choice [ 1 ]. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of engagement in sports for people with II [ 2 , 3 ]. Sports participation can improve cardiovascular endurance, muscle strength and motor skills [ 2 ], and it can enhance psychological well-being and cognitive skills improvement of this population [ 2 ], [ 3 ]. It can also facilitate the development of athletes’ transferable skills, like the ability to follow instructions and complete independent tasks [ 4 ]. Physical fitness and sports-related skills improvements serve as mediators for increased motivation in people with II [ 5 ]. However, only a limited number of people with II regularly participate in recreational or competitive sports, compared to people without II [ 6 ]. Due to the insufficient levels of sports participation and the additional health issues, their general fitness is significantly lower compared to the average population [ 7 , 8 ].

Moreover, the intellectual functioning (IQ≤70) and adaptive behaviour deficits in people with II [ 9 ] can negatively impact physical, physiological, psychological, and social aspects of their sports performance [ 10 – 13 ]. For instance, skills like self-regulation, decision-making, and learning by experience, which are important in sports performance and proficiency, are underdeveloped in persons with II [ 10 , 14 ]. Moreover, due to the impaired reasoning and judging abilities, athletes with II could misinterpret the others’ social behaviour (e.g., coaches, teammates and/or opponents) and respond differently to the environmental cues [ 15 ]. In running trials for example, the performance feedback that the social environment offers (e.g., coaches) cannot facilitate the ability of people with II to maintain a steady pace [ 13 ], a critical skill for optimal performance progression [ 16 , 17 ].

A theoretical framework that can explain the influence of coaches’ attitudes on athletes’ motivation, self-regulatory behaviour and sports performance progression, is Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [ 18 , 19 ]. SDT is a macro-theory of human motivation that makes a distinction between autonomous (e.g., individuals identify an activity as valuable or personally meaningful) and controlled motivation (e.g., individuals engage in an activity for external reasons) [ 18 ]. Autonomous motivation includes three types of motivation regulation–intrinsic regulation, integrated regulation and identified regulation. Controlled motivation includes two types of motivation regulation–introject regulation and external regulation. Both autonomous and controlled motivation direct behaviour, unlike amotivation, which refers to a lack of motivation [ 18 ]. According to SDT, motivation orientation depends on the satisfaction of three psychological needs [ 18 ]. Psychological needs refer to the inherent need for competence (e.g., through mastering an activity, positive reinforcement, winning a competition), autonomy (experience of volition) and relatedness (social environment’s support) [ 18 ]. These needs are critical in athletes with II as they guide their sports behaviour and facilitate their long-term engagement in sports [ 20 ]. However, the cognitive impairments (e.g., reasoning and judging), the high anxiety levels, and the low self-esteem of people with II [ 9 , 21 ], could negatively influence their autonomous motivation and in turn, hinder their sports performance progression [ 12 , 19 , 22 ].

In sports settings, coaches create a context through which their coaching style can support (need-supportive) or thwart (need-thwarting) athletes’ fulfilment of psychological needs [ 18 , 23 ]. On the one hand, need-supportive coaches can promote athletes’ autonomous motivation (more self-determined behaviour). This type of motivation has a significant impact on athletes’ long-term sports participation and performance progression, as it is associated with better learning, effort, and persistence [ 19 , 24 ]. On the other hand, need-thwarting coaches can promote athletes’ controlled motivation (externally regulated behaviour), which is considered less optimal as it is related to negative outcomes like burn-out and failure [ 18 , 24 , 25 ]. Due to the cognitive deficits of athletes with II (e.g., self-regulation and decision-making), this population tends to be more reliant on others [ 26 ] and could subsequently lead their coaches to adopt a more need-supportive coaching style. Moreover, these cognitive deficits could lead athletes with II to judge and respond differently to their coaches’ coaching styles compared to athletes without II [ 11 , 15 ].

In an effort to ensure an inclusive and fair sporting system, there has been a growing emphasis on mainstreaming disability sports in recent years [ 27 ]. Mainstreaming aims to integrate disability and non-disability sports organisations and to offer a range of possible and inclusive sports and exercise opportunities to people with disabilities [ 28 ]. Athletes of all abilities and their coaches play a central role in supporting the mainstreaming development. Therefore, to offer appropriate inclusive sports environments to people with II, it is imperative to understand more about their sports performance progression and motivations as well as the coach-athlete relationship. Additionally, a better knowledge about the differences of the aforementioned variables between people with and without II could facilitate a smoother mainstreaming in sports and offer more exercise pathways to people with II [ 27 ]. However, as athletes with II are one of the most understudied populations in sports settings, it is not well-documented how to properly include them in sports and how to guide coaches during this process [ 29 ]. Moreover, even if it is evident that coaches could affect athletes’ motivation and sports performance development, especially for athletes without II [ 23 – 25 ], it is not yet clear the impact of II on sports performance progression and motivation. Moreover, it is still unknown the role of coaches towards athletes with II and how this might differ compared to athletes without II. In this study, we chose to focus on coaches’ reports because by exploring coaches’ perceptions of their athletes’ performance progression and motivation, we can better examine the relationships between these perceptions and their coaching styles. We can also explore how coaches’ perceptions can promote (or restrict) the inclusion of people with II in sports [ 30 , 31 ]. The researchers are aware of the lurking danger of promoting intellectual ableism when a proxy respondent is preferred over a person with II [ 32 ] thus, their future studies aim to ‘give a voice to the voiceless’. For this study however, the exploration of the athletes’ motivation and progression from different perspectives will give us the opportunity to explore the coach-athlete relationship in sports settings more deeply [ 30 ].

Therefore, this study is based on the theoretical framework of SDT, and it aims to examine if: 1) there are differences in sports performance progression and motivation orientations between athletes with and without II as reported and perceived by their coaches, 2) there are differences in coaching styles between coaches of athletes with and without II, and 3) coaching styles are predictors of sports performance progression and motivation orientation in athletes with and without II. We hypothesize that: 1) coaches of athletes with II perceive their athletes to have made less progression in their sports performance and have adopted more controlled types of motivation compared to athletes without II, 2) coaches of athletes with II will adopt a need-supportive coaching style, compared to coaches of athletes without II, and 3) coaching styles are predictors of sports performance progression and motivation orientation in athletes with II and these predictors differ between the two groups (II and non-II).

Materials and methods

Participants and recruitment.

Recruitment of coaches of athletes with and without II was done through sports organisations, recreational centres and sports clubs via phone calls and e-mails (from January until May of 2021). The authors did not have access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection. Two hundred and sixty-six coaches with coaching experience in different sports (e.g., athletics, gymnastics, basketball, football etc.) consented to participate (45.9% coaches of athletes with II). Coaches’ average age was 40 ( SD = 16, range 17 to 81 years old) and 58.6% of them were male. The mean coaching experience for coaches working with athletes with II was 11 years ( SD = 10) while coaches of athletes without II had a mean average coaching experience of 15 years ( SD = 12). Both groups of coaches had experience coaching a variety of individual and team sports, like fencing, boccia, archery, athletics, football, and basketball. We included coaches who were fluent in English, had at least one year of coaching experience, and whose athletes were adolescents or adults (aged 12 or above) with or without II. Coaches were asked to act as proxy respondent for a group of persons (athletes with or athletes without II) [ 33 ] and provide their overall view of their athletes’ motivation, similarly to Rocchi [ 34 ]. For comparability purposes, their athletes with or without II were categorized into the ‘participation’ or ‘performance’ stage of sports development (focus on sports skills development with experience in local or regional, recreational competitive events) [ 35 ]. Athletes with II must meet the criteria for diagnosis of II as set by the British Psychological Society [ 9 ]: limitations in intellectual and adaptive functioning with an IQ ≤ 70, limitations in social, practical, and conceptual skills, and manifested before the age of 18 years. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Board.

Coaches of athletes with and without II completed questionnaires via an online platform (JISC). All coaches completed the 3 questionnaires overviewed below, which lasted approximately 20 minutes.

Rated performance (coaches’ reports of athletes’ sports performance progression).

This instrument is completed by coaches and is used to investigate the extent to which the athletes had progressed in the (a) physical, (b) tactical, (c) technical, and (d) psychological domain over the past year [ 36 ]. As this is an objective measurement of athletes’ perceived sports performance progression, the rate of progression was based on the sports performance abilities of the group of athletes and how coaches perceived their expected rate of improvement. These items are combined and form an intraindividual athletic performance scale (total performance progression). The scale uses a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strong regression) to 7 (strong progression) and showed excellent internal consistency [ 36 ]. Due to the lack of exercise and training routine during the COVID-19 outbreak, coaches were instructed to complete the questions retrospectively.

Revised sports motivation scale—perceived player motivation.

This instrument is founded on the SDT [ 18 ] and assesses coaches’ perspectives of athletes’ reasons for participating in sports (e.g., ‘because they feel better about themselves when they do play’; ‘because people around them reward them when they do play’) [ 34 , 37 ]. The scale measures sports motivation according to six types of behavioural regulation—intrinsic regulation, integrated regulation, identified regulation (under the autonomous motivation subscale; 9 items), introjected regulation, external regulation (under the controlled motivation subscale; 6 items), and amotivation (3 items). The scale uses a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (does not correspond at all) to 7 (corresponds completely). This instrument showed a strong factor structure and acceptable internal consistency [ 34 ].

Interpersonal behaviours questionnaire—self (IBQ-self).

This questionnaire is also founded on the SDT [ 18 ] and assesses coaches’ reports of their own interpersonal behaviours (IBQ-self) in sports settings [ 38 ]. The questionnaire consists of 24 items (e.g., ‘when I am with my athletes, I provide valuable feedback’; ‘when I am with my athletes. I pressure them to adopt certain behaviours’) and six subscales—autonomy-supportive, competence-supportive, relatedness-supportive (collectively they form the need-supportive scale), and autonomy-thwarting, competence-thwarting, and relatedness-thwarting (collectively they form the need-thwarting scale). The measure uses a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (completely agree) and showed a strong factor structure, internal consistency, and validity [ 38 ].

Statistical analysis

Perusal of the data using the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality suggests that the assumption of normality is violated. Therefore, we conducted a series of non-parametric analyses. To address aims 1 and 2 (e.g., differences in perceived total performance progression, perceived motivation orientation and coaching styles), we conducted a rank MANOVA to test if there were differences in autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, amotivation, total performance progression, need-supportive, and need-thwarting differences (six dependent variables) between the reports of coaches of athletes with and coaches of athletes without II (group; independent variable).

To address aim 3 (e.g., predictors of total performance progression and motivation orientation), we first performed two Spearman correlation analyses to assess the relationship between the variables for each group. Variables indicating significant correlations with coaching styles were entered into a series of Additive Nonparametric Regressions (Generalized additive model), with need-supportive and need-thwarting coaching styles as independent variables. The statistical analyses were performed using R , version 4.1.1, and the level of significance was set at p ≤ .05.

The rank MANOVA analysis showed that there were no group differences between coaches’ need-supportive ( p = .53) and need-thwarting style ( p = .41) and no group differences between perceived athletes’ amotivation ( p = .63). Furthermore, perceived autonomous motivation was significantly lower ( p < .001) and perceived controlled motivation was significantly higher in athletes with II compared to athletes without II ( p < .001). Finally, perceived total performance progression of athletes with II was significantly higher compared to athletes without II ( p = .01) (see Table 1 for the descriptive data, and Fig 1 for the univariate post-hoc comparisons between the variables).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Univariate post-hoc comparisons of Need-Supportive, Need-Thwarting, Total Performance Progression, Autonomous Motivation, Controlled Motivation and Amotivation for athletes with and without II. T = T Value, P = P Value (* shows the mean differences are significant at the .05 level; ** shows the mean differences are significant at the .01 level; *** shows the mean differences are significant at the .001 level).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.t001

Results of the Spearman Correlation analyses indicated that both coaching styles (need-supportive and need-thwarting) were significantly correlated with autonomous motivation and amotivation in II and non-II group ( p < .001). Additionally, both coaching styles were significantly correlated with the total performance progression in non-II group ( p < .001) (see Table 2 ). Therefore, only these variables were entered into the series of Additive Nonparametric Regression analyses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.t002

A series of Additive Nonparametric Regressions were run to examine if need-supportive and need-thwarting were predictors of autonomous motivation and amotivation in the II group. A second series of Additive Nonparametric Regressions were run to examine if need-supportive and need-thwarting were predictors of autonomous motivation, amotivation and total performance progression in non-II group. Results showed that a need-supportive coaching style positively predicted autonomous motivation in athletes with and without II ( p < .001, adj . R 2 = .28 and p = .00, adj . R 2 = .47 respectively). It also negatively predicted amotivation in athletes with II ( p = .00, adj . R 2 = .25). Additionally, a need-thwarting coaching style positively predicted amotivation in athletes with and without II ( p = .02, adj . R 2 = .25 and p < .001, adj . R 2 = .37 respectively), and negatively predicted autonomous motivation in athletes without II ( p = .00, adj . R 2 = .47). Fig 2 presents the partial effects plots with the approximate significance of smooth terms for predictors of autonomous motivation and amotivation in athletes with and without II. Neither coaching style significantly predicted total performance progression in both groups.

Edf = effective degrees of freedom, P = P Value (* shows the mean differences are significant at the .05 level; ** shows the mean differences are significant at the .01 level; *** shows the mean differences are significant at the .001 level).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.g002

This study aimed to shed light on athletes’ sports performance progression, athletes’ motivation orientations and coaching styles differences, as well as the relationships between these factors, as reported and perceived by coaches of athletes with and without II. The results did not fully support our first hypothesis that coaches of athletes with II perceive their athletes to have made less progress in their sports performance and have adopted more controlled types of motivation compared to athletes without II. More specifically, coaches’ reports indicated that athletes with II were perceived to progress more in their sports performance (total performance progression) compared to athletes without II. However, as we hypothesised, coaches reported and perceived that athletes with II adopt more controlled types of motivation than athletes without II, and less autonomous types of motivation, than athletes without II.

A reason that total performance progression of athletes with II is perceived to be higher could be due to lower long-term engagement in sports and the lower levels of physical fitness and muscle strength of this population compared to athletes without II that previous studies reported [ 39 , 40 ]. However, due to the nature of the Rated Performance questionnaire (was based on the perceived physical, tactical, technical, and psychological progression of the athletes) and the plethora of different sports that coaches were coaching, we approach this argument with caution. More research based on objective measurements is needed to explore the relationships between training age and physical fitness (e.g., fitness assessments that test the strength and muscle mass alternations of athletes) with the sports performance progression of athletes with II [ 41 , 42 ].

However, as this study was based on coaches’ perceptions, a more appropriate explanation for these findings could be the disability stereotype where achievements by people with disabilities are rated more positively from the able-bodied society [ 43 ]. Thus, coaches of athletes with II might unconsciously adopt different standards for sporting success and overestimate their total performance progression [ 44 ]. For instance, coaches may have relatively low expectations from their athletes with II, while a great physical, tactical, technical, and/or psychological progression of them could be perceived by the coaches as paradoxical [ 38 ]. Additionally, coaches of athletes with II tend to adopt a mentorship role, focus less on their athletes’ sports performance development, and potentially underestimate the importance of nurturing the athletic identity that athletes with II may wish to develop [ 45 ]. These attitudes may be well-intentioned however, when athletes with II accomplishments are portrayed as surprising and/or inspirational it can perpetuate ableism [ 38 , 44 ]. If these unintentional (but still ableist) attitudes occur, this could make the mainstreaming of disability sports more challenging for this population. Thus, there is a necessity to reshape coaches’ assumptions of what athletes with II can and cannot do and help them set realistic sports performance goals for their athletes. Moreover, even if we tried to recruit coaches who are working with athletes with a similar stage of sports development, we recognise that disability and non-disability sports organisations are not fully integrated [ 27 ]. As a result, the training sessions, the opportunities for sports performance development, and participation in competitive events may vary for athletes with and without II [ 27 ]. Consequently, the coaches’ expectations regarding their athletes’ improvement may also differ between the two groups and could partially explain the findings observed in this study.

The results also indicated that athletes with II adopt more controlled types of motivation compared to athletes without II and less autonomous types of motivation (as perceived by their coaches). Previous research has shown that athletes with II exhibit higher ego orientation and lower self-regulation compared to athletes without II [ 10 , 46 ]. This could partly explain the lower levels of long-term participation in sports of athletes with II compared to athletes without II [ 47 , 48 ], as autonomous motivation functions in a dyadic relationship with self-regulation and facilitates athletes’ long-term exercise engagement and persistent sports behaviour compared to athletes who adopt more controlled forms of motivation [ 18 , 24 , 25 ]. The higher level of perceived controlled motivation could be a result of the high levels of anxiety, decreased confidence and social phobia experienced by people with II and may influence their sports motivation [ 49 , 50 ]. In addition, the lack of awareness and societal support that athletes with II reported [ 51 ], could hinder the fulfilment of their relatedness’ needs [ 18 ] which could, in turn, fuel more controlled types of motivation compared to athletes without II. However, the motivational differences between athletes with and without II could have occurred due to the difficulties of proxies (such as coaches) to recognise that people with II can have a good, personally meaningful life [ 32 , 43 , 44 ] and accept the role of people with II in their own autonomous decision-making [ 32 ]. Coaches in sports settings tend to prioritise their own aspirations and perspectives regarding the needs of people with II, potentially overshadowing their athletes’ sports motivations [ 45 ]. In addition, coaches may observe that the social environment (e.g., parents) hinders the decision-making of people with II and consequently adopt an overprotective stance towards them [ 45 ]. Thus, coaches may perceive that the sports participation of athletes with II depends more on external and less on internal motivations compared to athletes without II, but further research is needed to explore the level of intellectual ableism in coaching settings and give equal attention to both athletes with II and their coaches [ 32 ].

The results of our study did not support our second hypothesis, indicating that the coaching style between the two groups is similar. Given the coaching experience of the participants, with both groups having an average coaching experience of over 10 years, it is unlikely that the observed similarities in coaching styles can be attributed to a lack of experience or their experience differences. A possible explanation for the coaching style similarities could be that most of the coaches of athletes with II come from mainstream sports and have a traditional coaching education background [ 52 ]. Previous studies in sports for people without II showed that coaching behaviour is influenced by athletes’ motivation [ 53 , 54 ]. However, the different motivation orientations of athletes with and without II and the similar coaching styles of their coaches, indicate that coaching behaviour towards athletes with II seems less adapted to athletes’ motivation. Moreover, these findings could indicate that coaches may have difficulties in adapting their approach to the needs of athletes with II; thus, more effort is needed to enhance the autonomous motivation of this population. Due to the reciprocal relationship between coaching behaviour and athletes’ motivation [ 54 ], future qualitative research should further investigate the coach-athlete relationship in II sports, coaches’ practices, how and why they implement them, and how beneficial this could be for their athletes’ long-term sports participation and development.

The series of additive nonparametric regression analyses partially supported our third hypothesis, indicating that coaching styles are predictors of motivation orientation in athletes with II and that these predictors differ between the two groups (II and non-II). Specifically, the results show that the coaches’ need-supportive style is a predictor of the autonomous motivation (positive) and amotivation (negative) of athletes with II. At the same time, coaches’ need-thwarting style positively predicts amotivation in this population ( Fig 2 ). These findings indicate the importance of the coach-athlete relationship in II sports and suggest that athletes with II may have the capability to respond accordingly to different coaching styles contrary to common beliefs [ 15 ]. For example, athletes with II may feel a sense of ownership and enjoyment as well as reduced feelings of disinterest when their coaches take time to understand their feelings and needs and provide them with choices and encouragement (need-supportive coaching style) [ 23 , 25 ]. Additionally, they may feel disengaged, demotivated, and uninterested in participating in sports when their coaches tend to be controlling or neglectful of their needs (need-thwarting coaching style) [ 23 ].

The findings also highlight the necessity of coaches to nurture the basic psychological needs of athletes with II. Coaches of athletes with II may wish to provide their athletes with choices and meaningful rationales for the assigned exercises and show trust in their capabilities regardless of their cognitive limitations. They could also consider giving them clear and simplified instructions and providing them the opportunity to express their needs and anxieties in a socially safe and supportive sports environment [ 24 ]. These attitudes may be essential for athletes with II, a population dealing with increased anxiety, social phobia, and decreased confidence [ 49 ] and tending to adopt more controlled types of motivation. Coaches’ need-supportive style may increase athletes’ chances to adopt more autonomous motivation regulations, avoid amotivation, increase their positive affect [ 23 ], facilitate their self-regulatory development and inspire their long-term engagement in sports [ 24 ]. Contrariwise, coaches who thwart athletes’ basic psychological needs could engender feelings of pressure, failure, and loneliness [ 23 ], demotivate them from continued sports participation (amotivation), and increase their chances of depression and burnout [ 23 ]. Thus, it is optimistic that coaches of athletes with II are trying to connect with their athletes, promote the social interaction, and focus on their athletes’ positive emotions in sports settings. However, more research is needed to assess the efficiency of their approach and how they can promote a fertile ground for their athletes’ long-term engagement in sports [ 45 ].

It is also important to explore the different role that the coaching styles have in athletes with and without II. It seems that the need-supportive style predicts autonomous motivation only in athletes with II. On the other hand, the need-thwarting style predicts amotivation only in athletes without II. The impaired cognitive abilities of athletes with II could lead them to respond differently to environmental cues (e.g., coaches’ attitude) and react dissimilarly to coaching styles compared to athletes without II [ 9 , 11 , 13 ]. These differences, along with the different motivation orientations between athletes with and without II, should be taken into consideration in future sports disability education programs. It is thus crucial to educate coaches of athletes with II on how to effectively deal with the cognitive deficits of this population, interact with them appropriately, and provide effective support for their basic psychological needs [ 52 , 55 ]. Nonetheless, education for coaches regarding disabilities will be beneficial and will facilitate the mainstreaming development in sports only if the coaches acknowledge that each athlete (II and non-II) has a unique personality, and that they should adapt their behaviour to each athlete’s needs in order to foster meaningful athlete-coach relationships [ 56 , 57 ]. Currently, coaching education opportunities within disability sports are still lacking, which makes it even more challenging for coaches to gain any advanced learning about the most progressive and effective ways to coach athletes with II and offer them inclusive sports opportunities [ 52 ].

This study presented some limitations that need to be addressed. First, due to the lack of validated self-report instruments that measure motivation orientations in athletes with II, this study was based on coaches’ perception of athletes’ motivation orientations. However, the communication difficulties that athletes with II experience could lead their coaches to misinterpret their needs, behaviours, and motives [ 58 ]. Future studies should investigate the role of significant others (e.g., coaches, carers, parents, peers) in fostering different motivation orientations. Future research should also aim to develop appropriate and valid instruments that measure motivational regulations among athletes with II. Another limitation of the study is the absence of qualitative feedback in the survey data. Qualitative approaches, like interviews with coaches and athletes with II, could provide a deeper understanding of the coach-athlete relationship in disability sports and capture nuanced information that our quantitative approach alone may not revealed [ 59 ]. Thus, future studies could use a mixed-methods approach (combining qualitative and quantitative methods) to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the problem [ 59 ]. Future studies should also ensure the active involvement of participants with II and their contribution to the research process. Additionally, it is crucial for these studies to also consider other relevant stakeholders (e.g., family members, support staff, policy makers) in examining the coach-athlete relationship in disability sports and the inclusive practices towards athletes with II [ 45 ]. Another limitation is also the lack of device-based measurements that investigate the sports performance progression of athletes. A criticism of self-report measurements of sports performance development is that they could be affected by coaches’ bias towards athletes who have specific roles within the team [ 60 ]. However, due to COVID-19 restrictions during the data collection process, it was not feasible to include device-based measurements of sports performance. Future work could integrate both device-based and self-report performance assessments to gain a better understanding of athletes’ progression and better support their long-term development in sports performance settings [ 60 ].

In summary, this paper gives some insights about the significance of the coach-athlete relationship in sports and the importance of a need-supportive coaching style to enhance autonomous motivation and prevent the amotivation of athletes with II. While self-reported coaching styles were similar between coaches of athletes with and coaches of athletes without II, their perceptions of their athletes’ performance progression and motivation orientations seemed to differ. This might have occurred due to the differences in sports opportunities and experiences between athletes with and without II and/or due to the different sports standards that their coaches adopt. Thus, it is important to offer appropriate training and knowledge to coaches about disability sports and the adaptations needed to effectively coach athletes with II and to appropriately offer them inclusive sports activities.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. strobe statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.s001

S2 Checklist. PLOS ONE clinical studies checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296164.s002

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Burns J, Khudair M, Hettinga FJ. Intellectual Impairment. In: Davison R, Smith PM, Price M. J, Hettinga FJ, Tew G, Bottoms L, editors. Sport and Exercise Physiology Testing Guidelines: Volume I—Sport Testing: Routledge; 2022. p. 347–55.

- 9. British Psychological Society. Learning Disability: Definitions and Contexts. Leicester: British Psychological Society; 2000.

- 18. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, USA: Plenum Press; 1985.

- 21. Hatton C. Intellectual disabilities–classification, epidemiology and causes. In: Emerson E, Hatton C, Dickson K, Gone R, Caine A, Bromley J, editors. Clinical psychology and people with intellectual disabilities. Chichester: Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. p. 3–22.

- 29. Teodorescu S, Bota A. Teaching and coaching young people with intellectual disabilities: a challenge for mainstream specialists. In: Hassan D, Dowling S, McConkey R, editors. Sport, Coaching and Intellectual Disability: Routledge; 2014. p. 103–19.

- 33. Cohen M. Proxy respondent. In: Lavrakas PJ, editor. Encyclopedia of survey research methods Sage Publications, Inc.; 2008. p. 632–4.

- 35. Eady J. Practical Sports Development. London: Pitman; 1995.

- 52. Campbell N, Stonebridge J. Coaching athletes with intellectual disabilities. Same thing but different? In: Wallis J, Lambert J, editors. Sport Coaching with Diverse Populations: Theory and Practice. 1st ed: Routledge; 2020.

- Frontiers in Sports and Active Living

- Sports Coaching: Performance and Development

- Research Topics

The Role of Coaches in Sports Coaching

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

In the sports coaching process, the coach is in charge of mediating the learning and performance of athletes, which makes him/her one of the protagonists of the sports environment. Specifically, the coach must make decisions on how to control a series of elements that make up this complex process and provoke ...

Keywords : coach, training, training tasks, coaching, instructor

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines, participating journals.

Manuscripts can be submitted to this Research Topic via the following journals:

total views

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Articles on sports coaching

Displaying all articles.

In sport, abuse is often dismissed as ‘good coaching’

Zoe John , Swansea University

With another case of abuse in elite sport, why are we still waiting to protect NZ’s sportswomen from harm?

Holly Thorpe , University of Waikato and Kirsty Forsdike , La Trobe University

Gymnastics NZ has apologised for past abuses — now it must empower athletes to lead change

Georgia Cervin , The University of Western Australia

Here are the best parents to have around, according to youth sport coaches

Nick Holt , University of Alberta

DJ Durkin’s firing won’t solve college football’s deepest problems

Joseph Cooper , University of Connecticut and Jasmine Harris , Ursinus College

More money may be pouring into women’s sport, but there’s still a dearth of female coaches

Fraser Carson , Deakin University and Julia Walsh , Deakin University

Why so many children’s sports coaches are unqualified and underpaid

AJ Rankin-Wright , Leeds Beckett University and Sergio Lara-Bercial , Leeds Beckett University

Five ways to deal with burnout using lessons from elite sport

Peter Olusoga , Sheffield Hallam University

Blurred lines: building winning athletes in sport or just plain bullying?

Neil Gibson , Heriot-Watt University and Kevin O'Gorman , Heriot-Watt University

Playing is not coaching: why so many sporting greats struggle as coaches

Steven Rynne , The University of Queensland and Chris Cushion , Loughborough University

Here’s to coaches, unsung heroes and role models for social change

Andrew Bennie , Western Sydney University and Nicholas Apoifis , UNSW Sydney

Related Topics

- Abuse in sport

- Elite sport

- New Zealand stories

- sports coach

- Sports coaches

- Student athletes

Top contributors

Associate Professor, Health and Physical Education/Sport Development, Western Sydney University

Lecturer in Politics & International Relations, UNSW Sydney

Director of Sport, Performance and Health, Heriot-Watt University

Former Professor of Management and Business History

Associate Professor, Sports Coaching; Affiliate, UQ Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, The University of Queensland

Professor of Coaching and Pedagogy; Director of Sport Integration, Loughborough University

Senior Lecturer in Sport & Exercise Psychology, Sheffield Hallam University

Assistant Professor, Department of Sport and Exercise Sciences, Durham University

Senior Research Fellow, Leeds Beckett University

Assistant Professor in Coaching and Sport Psychology, Deakin University

Senior Lecturer in Sports Coaching, Deakin University

Assistant Professor of Sociology, The University of Texas at San Antonio

Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership, University of Connecticut

Professor in Kinesiology, Sport, and Recreation, University of Alberta

Honorary Research Fellow, The University of Western Australia

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

Advertisement

Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health in sports: a review

- Published: 20 April 2023

- Volume 19 , pages 1043–1057, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Akash Shukla 1 ,

- Deepak Kumar Dogra 1 ,

- Debraj Bhattacharya 1 ,

- Satish Gulia 2 &

- Rekha Sharma 3

2957 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Global pandemic, lockdown restrictions, and COVID-19 compulsory social isolation guidelines have raised unprecedented mental health in the sports community. The COVID-19 pandemic is found to affect the mental health of the population. In critical situations, health authorities and sports communities must identify their priorities and make plans to maintain athletes’ health and athletic activities. Several aspects play an important role in prioritization and strategic planning, e.g., physical and mental health, distribution of resources, and short to long-term environmental considerations. To identify the psychological health of sportspeople and athletes due to the outbreak of COVID-19 has been reviewed in this research. This review article also analyzes the impact of COVID-19 on health mental in databases. The COVID-19 outbreak and quarantine would have a serious negative impact on the mental health of athletes. From the accessible sources, 80 research articles were selected and examined for this purpose such as Research Gate, PubMed, Google Scholar, Springer, Scopus, and Web of Science and based on the involvement for this study 14 research articles were accessed. This research has an intention on mental health issues in athletes due to the Pandemic. This report outlines the mental, emotional and behavioural consequences of COVID-19 home confinement. Further, research literature reported that due to the lack of required training, physical activity, practice sessions, and collaboration with teammates and coaching staff are the prime causes of mental health issues in athletes. The discussions also reviewed several pieces of literature which examined the impacts on sports and athletes, impacts on various countries, fundamental issues of mental health and the diagnosis for the sports person and athletes, and the afterlife of the COVID-19 pandemic for them. Because of the compulsory restrictions and guidelines of this COVID-19 eruption, the athletes of different sports and geographical regions are suffering from fewer psychological issues which were identified in this paper. Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to negatively affect the mental health of the athletes with the prevalence and levels of anxiety and stress increasing, and depression symptoms remaining unaltered. Addressing and mitigating the negative effect of COVID-19 on the mental health of this population identified from this review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of the lockdown period on the mental health of elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review

Vittoria Carnevale Pellino, Nicola Lovecchio, … Matteo Vandoni

The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions on Youth Athlete Mental Health: A Narrative Review

Peter Kass & Tyler E. Morrison

A systematic review of interventions to increase awareness of mental health and well-being in athletes, coaches and officials

Gavin Breslin, Stephen Shannon, … Gerard Leavey

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

COVID-19 is an arising irresistible illness brought about by the newfound Extreme Intense Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first patient with COVID-19 was identified in Wuhan, Hubei territory as per the research of WHO [World Health Organization] in 2020. In addition, contamination has spread quickly all over the world which resulted in numerous extreme and lethal clinical cases [ 1 ]. It is identified as a highly transmitted disease which can transmit from one person to another person through the droplets of respiration, hands, nose, mouth etc. and also a high infectiousness disease [ 2 ]. The number of mortalities and grimness around the world due to COVID-19 have raised critical general health and well-being concerns. Additionally, identifying, diagnosing, and treating those who were infected, as well as developing medicines, antibodies, and treatments was focused on by all countries and the World Health Organization to decrease the effect of this pandemic [ 3 ]. Finally, governments were constraining nearly a worldwide quarantine [ 4 ]. As a result, all the people maintained social distancing to overcome this issue. Other countries announced several conditions like no contact between people and also lockdown had been declared [ 5 ]. The refugee crisis has also affected the world of sports affairs.

Due to this pandemic, several individuals get affected which leads to disruption, anxiety, stress, stigma, and xenophobia. In a society or community, the act of an individual affects the agitation of the pandemic which contains the level of severity, degree of flow, and aftereffects [ 6 ]. The complete information about the virus and its effects must be known prevent it. To control the spreading of the virus, regional lockdowns were implemented due to the people-to-people transmission of the SARS-CoV-2. The transmission chain has been broken by employing isolation, social distancing, and closing of educational institutes, workplaces, and entertainment venues by which people stay in their homes [ 7 ]. The social and mental health of people gets greatly affected because of these strict actions throughout the board [ 8 ]. The WHO recommends people stay active and available at home to reduce social relationships during the initial wave of COVID-19 and to prevent the spread of the virus. Throughout the world, after the decrease in the count of COVID-19 cases [ 9 , 10 ], and due to the limit of outbreaks in the initial stage, a survey shows that there is a rise in the COVID-19 cases in the second wave in many regions of the world [ 11 ]. Zhao et al . [ 12 ] say that the second wave of infections will be indicated by the control measures and social distance carried out during the first wave of COVID-19 transmission. Due to this, the athletes faced challenges in doing their regular activities with the supervision of their coach and scientific experts, during the placement period.

Several efforts were carried out to prevent the pandemic situation, but there is no clear information about what will be the next steps followed in the upcoming days. The long-lasting effects of Coronavirus have given great worry to the global environment such as declined economy, venture surety, worldwide market stocks, human well-being, daily groceries supply and medical emergency services. To control the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, strict actions were followed by the governments like severe lockdowns, restriction of social groups, and organisations like sports events and also unnecessary travel has also been prohibited which greatly affects the sports industry and athletes [ 13 ]. For this reason, the athletes were incapable to regulate their regular training sessions as well not participate in any sports events due to suspensions. Further, Turgut et al. [ 14 ] reported the cancellations and postponements of various global sporting events to follow the global health recommendations and to restrict the spread of the infection.

By considering the risk of transmission and the health problems for both the spectators and the field players, several nations have postponed the local professional football leagues [ 15 ]. Severe economic issues and lack of income were the results of COVID-19 and the elite football clubs also face several problems due to this pandemic [ 16 ]. The final match of the UEFA Champions League and other fewer games were postponed by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) to March 2020, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the government of Japan also postponed the Tokyo Olympics of 2020 to July 2021 in which there is no change in the name as 2020 Tokyo Olympics [ 17 ]. Totally of about 57% of the 11,000 athletes who have registered for the postponed Olympic games have already met the requirements, following the International Olympic Committee (IOC) However, the majority of these athletes are now confined as a result of the COVID-19 restriction, which was extended till 2021. Therefore, because of the pandemic these big decisions of cancellation and delaying the tournaments were taken due to which many athletes confronted tight limitations to proceed with their normal preparations or practices. Health authorities prescribe these constraints to avoid the public gathering during matches and events that might work to a quick spread of Coronavirus, bringing about extra tension in the medical services framework [ 18 , 19 , 20 ].

To evade the COVID-19 infection during the lockdown self-isolation, limitations, social disconnection arrangements and an environment of uncertainty created an adverse effect on the populace's mental health [ 21 ] and already available evidence appears to affirm these forecasts [ 22 ]. During the first month of internment, nearly 15.8% and 21.6% of the total population of Sain faced depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic symptoms as per the report of González-Sanguino et al . [ 23 ]. Further, WHO [ 18 , 19 , 20 ] is also concerned about these mental health and psycho-social issues due to this pandemic.

However, to understand these outcomes, there is a need to study the results of the coronavirus pandemic in the sports setting. In that context, Trabelsi et al. [ 24 ] also reported that few coaches, sports psychologists and even psychiatrists found some mental issues in athletes, that may cause adverse consequences in their life. Furthermore, Reardon et al. [ 25 ] identified in a narrative review that elite athletes were suffering from various psychological issues at rates identical to or surpassing the common population due to COVID-19. Moreover, the field specialists cautiously screened and observed the athletes during the Coronavirus pandemic and expressed those athletes needed a mental advisory for adjustments. Similarly, Turgut stated that the new measures of self-segregation from others and quarantine affects exercise, practice routine as well as lifestyle resulting in prompt physical and mental challenges for athletes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, elite athletes encountered a lot of stressors during their career, the COVID-19 restrictions seem to have amplified all the stressors with negative consequences on the mental health of athletes. Unfortunately, the present literature does not seem to clarify the possible causes and effects of COVID-19 restrictions on athletes. Subsequently, the present narrative review aims to describe the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown influenced the mental health of elite athletes. Specifically, the primary objective of this review is to identify the common psychological distress and stress responses in elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, this study aims to identify factors, either positive or negative, related to psychological distress in elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic from various research articles.

Impact of COVID-19 on mental health

Several reasons were identified for this. The people who combat the public health factors (like vaccination) and how they deal with the risk of infections and following losses which was mainly due to the psychological measures. The treatment of any infectious disease like COVID-19 is one of the main problems. The maladaptive behaviours, emotional distress and defensive responses were the results due to the Psychological effects of the pandemic [ 26 ]. The people who were affected psychologically will be harsher. We need to accept that, there will be a low lifespan for the people who were affected mentally and this results in poor physical health in normal cases rather than in other populations [ 27 ]. People who already have mental health or use drug problems are more likely to contract COVID-19, and they may face difficulties getting tested or treated and suffer unfavourable medical or mental impacts as a result of the pandemic.

Secondly, from this study, it is predicted that an increase in anxiety and depression symptoms, with some individuals, eventually developing post-traumatic stress disorder, among those who do not already have these diseases. From the evidence, a suggestion is made that throughout the current pandemic, this risk was not fully recognized in China [ 28 ].

Third, an assumption is made that, the people who work in public health, primary care, emergency services, emergency departments and intensive or critical care may face several psychological disorders. While this risk to healthcare workers has been formally identified by the World Health Organization, more needs to be done to manage anxiety and stress in this population and, in the long run, to help prevent burnout, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 29 ]. However, physical exercise training generally has health benefits and assists in the prevention of several chronic diseases. Moreover, physical activity improves mental health by reducing anxiety, depression, and negative mood and improving self-esteem. Therefore, the beneficial effects of adapted physical activity, based on personalized and tailor-made exercise, in preventing, treating, and counteracting the consequences of COVID-19 are analysed [ 30 ].

Consequently, it is important to identify some of the unique challenges this population currently faces, and understand where our student-athletes are mentally and physically. This is to ensure their needs are addressed, and the health and well-being of this population are protected. [ 31 ] assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Canadian high-performance secondary school student-athletes. Student-athletes should be provided additional mental health support during this maelstrom of changes. In particular, additional mental health support for student-athletes should be anticipated in this maelstrom of changes; specific in-home virtual training during the COVID-19 outbreak should be further strengthened and improved to protect the mental and physical health of the athletes, especially to reduce the risk of anxiety and depression.

Impact of COVID-19 on sports

Throughout the world, the COVID-19 virus has been spread virtually, and to stop the spread of this disease, companies, schools, and colleges have been locked down, and general social life like sports and physical activities has also been hindered. The challenges faced by the athletic industry have been mentioned in the COVID-19 lockdown policy. As a result of the fast transmission of this coronavirus, millions of people have lost their lives, the largest indoor and outdoor sports events have been affected, and without the view of competitions the national and international level sports have been postponed or cancelled or rescheduled or location changes happened [ 32 ]. Sports events have been greatly affected by the COVID-19 virus and there are rescheduled international events like the Olympics which have been discussed earlier.

In overall history, this is the first time the cancellation of Olympic Games due to a medical issue [ 33 ]. The financial loss is not only faced by the country Japan but also the 11,000 Olympic athletes and 4400 Paralympians who participated in several sports events of the Olympics also faced this problem. The Olympics is one of the rare and great opportunities for athletes to establish their talents through participation in competitions in front of the total world. Every participant had worked hard and undergo much training for this. During March and April 2020, football clubs would not be required to release players for national teams, according to a FIFA announcement made on March 13, 2020. Without any response, the players have the opportunity to decline. As per the suggestion of FIFA, all international matches must take place outside of the slots, however, the final choice is based upon the administrators of the competition member associations for friendly matches [ 34 ]. Other sporting events, including the Wimbledon championship, the basketball and football tournaments, the athletics championship, handball and ice hockey, cricket, rugby, skiing, weightlifting, and wrestling were able to modify their schedules or can cancel their competitions altogether. For the top athletes, their professional career gets affected greatly due to this rescheduling of the Olympics and several National and International sports events. Along with the discussion about the performance of the athletes, the effects of COVID-19 on sports events must also be considered. Based on factors like location, opposition, score, number of recovery days, and tactical system, the performance of athletes relies [ 35 ].

Because of this lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, throughout the world, there are millions of jobs at risk. Rather than the sports person, the people who were engaged in retail and other services, sports industries along with the sports events and leagues that contain transportation, infrastructure facility, travel, tourism, catering, and media broadcasting in the field of sports were also get affected [ 36 ]. A lot of pressure arises among the athletes and professional players because of this postponement of the competitions. Initially, there is no support from the sponsors if they decide to make them fit in the home itself.

Several educational institutions along with sports education are also get affected because of the COVID-19 lockdown, and those stakeholders the local and national ministries, public and private educational institutions, sports organizations, NGOs and the business community, teachers, scholars, coaches, athletes, parents and some young people were also involved.

Impact of COVID-19 on physical activity

Due to the cancellation of sports events during the COVID-19 lockdown, all the other outdoor activities were also restricted. Furthermore, gyms, stadiums, pools, dance and fitness studios, physiotherapy clinics, and parks were forced to close. These factors encouraged athletes to alter their fitness routine and train at home, where they are frequently not observed by qualified health workers or trained coaches. Several athletes have their gym at home or other pieces of exercise equipment which they can use to practise regularly during a lockdown. Their current level of physical fitness should be maintained, or at the very least not decreased, during the home activity period [ 37 ]. However, most people are unfortunately unable to be actively involved in their regular outside individual or group sporting or physical activities. A high level of physical fitness is required by elite athletes irrespective of the specific type of sport. Generally speaking, elite athletes avoid long periods of rest during and at the end of the competitive season [ 38 ].

The immune system and the anti-viral defences were greatly affected because of continuous exercise every day [ 39 ]. A low regulate exercise is resulted due to the order of stay-at-home by the government and closures of parks, gyms, stadiums, and fitness centres to stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Since regular exercise can boost the immune system of a sportsperson and can able to treat several co-morbidities like obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and severe heart diseases that make athletes more prone to infections like COVID-19 so it is considered an unacceptable instruction [ 40 ].

Since they affect several sports damage processes and have the potential to improve repeat intervention and prevention, psychological elements underlying the various stages of sports injury are becoming more and more essential [ 41 ]. Rather than the new concept in history, the confinement scenario resulting from COVID-19 shares several issues with the various stages of sports injury encountered by athletes. The sports activity can be reduced due to some inference, reduction in autonomy, alterations in the sports environment, as a single or group there is a lot of chances to increase their records in the sports field, prohibition of activities that are not related with it, personal and family life changes like earlier retirement because of the alterations in the schedule of sports events. Now there is the existence of deeper problems like abuse of substances, social distance, depressive or anxiety episodes, suicidal thoughts, self-esteem problems, and poor sleep quality. Because a poor perception of the quality of sleep can harm the health of a sportsperson, along with the life of the sportsperson the latter factor is also included [ 42 ]. Long periods of isolation may lead to personal growth and development of the psychological processes of sports exercise, which is under the discussion with the writers. There are many adjustments made by sportspersons because of the existence of restrictions throughout the world since they lack the equipment or appropriate areas to develop their training routines effectively [ 43 ]. Because of the prohibition or postponement of all the local, national, and worldwide contests, this fact has prompted us to investigate how the athletes face this complex situation and their issues. Consequently, during this complicated scenario, particular emphasis should be dedicated to specific exercise interventions tailored for subjects and athletes recovering from COVID-19 [ 44 ]. Studying the psychological effects both good and bad that this situation may have a great interest in the individuals.

For the athletes, both the physical and mental issues get increased due to this continuous COVID-19 lockdown. There arises an unstable life for sports players due to the prohibition and rescheduling of sports events. Professional players or athletes feel stressed because they are pushed to the situation to handle all the problems behind them. The level of worry, stress and anxiety may get increased due to the unstable future [ 45 ].

However, to the researcher’s awareness, how far the mental health of the athletes and professionals get affected due to this pandemic has been examined through several researches and surveys. During the continuous lockdown of COVID-19, athletes and sportspeople have faced a lot of issues like difficulties in sleep, sadness and depression rather than an increase in their physical activities [ 46 ]. To address these mental issues and information and illuminate the sports fraternity as well as the general society about the mental challenges an athlete is facing during this COVID-19 outbreak, this review article's impact of a COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health in sports was taken. To examine the current status of the professional athletes who went for a break during the pandemic period and to measure their mental health several surveys have been carried out. An investigation was also carried out to identify the physical and mental activity of the athletes while they stay at the home.

Methodology

The scoping review was carried out for the criteria and procedures outlined in the available systematic literature data factors and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) with the Scoping Reviews extension.

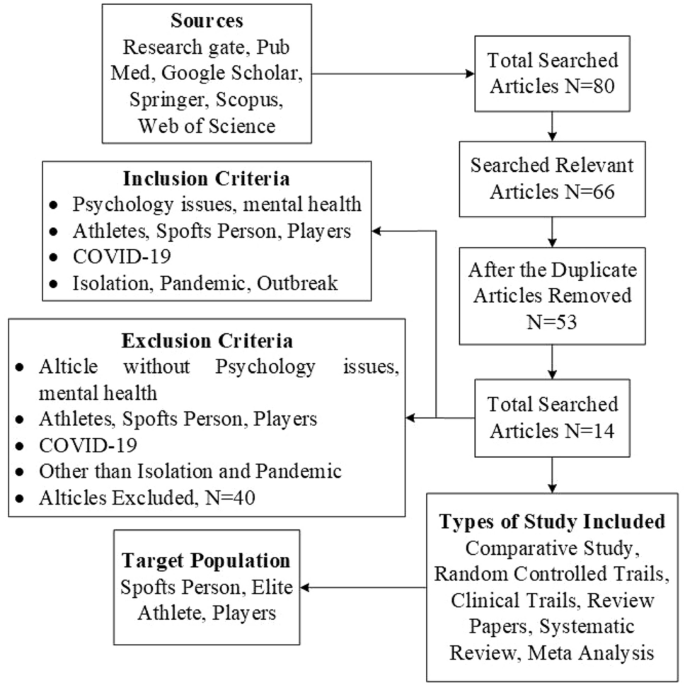

The available literature on aerobic exercise intervention on body composition in obese females was considered for the present study. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. From the sources like Research Gate, Pub Med, Google Scholar, Springer, Scopus, and Web of Science, a total of 80 research articles were gathered for the study and among that 14 sample papers were selected by making use of keywords like COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and athletes. Initially, the selected papers were examined whether they are related to the effect of the pandemic on the sportsperson and to confirm this, their respective reference papers were also examined for the full-text articles. The reviews of the particular research papers were also considered. Some of the measures developed to confirm the eligibility were (1) Population: sports person, professional athletes, players, (2) Intervention: COVID-19 pandemic, (3) Types of Study: a comparative study, randomly controlled trials, clinical trials, review papers, systemic review, and meta-analysis, and (4) Outcomes: an establishment of good and fine result related to the psychological health. Age, injury form, or research design will not be avoided. Studies which are not in English, not publishing results, and are not relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic were removed.

Flow chart of PRISMA

Scope of PRISMA

To provide guidelines for the creation of protocols and for scientific reviews and meta-analyses that evaluate the efficacy of treatments, the PRISMA has been developed. Without the examination of efficacy, the PRISMA undergoes several reviews because of the fewer protocol instructions, writers are recommended to adopt. A protocol has been demonstrated by the research as a document that defines the reasoning, intended purpose, and intended methodology approach of a systematic review before it begins.

The authors who are involved in the development of systematic review procedures for publication, general consumption, or other purposes should PRISMA initially. To identify whether the protocol contains crucial information, it will be useful for the candidates who write review procedures and as a tool for the reviewers. To get a conclusion about a review, the journalists and reviewers make use of PRISMA to identify the correct protocol.

The structure of this document is the same as the previously established journalistic standards, such as the PRISMA Explanation and Elaboration document; it provides thorough justifications and evidence-based justifications for each checklist item. Examples of effective reporting for each checklist item have been discovered which use systematic review and meta-analysis techniques and are provided throughout this document to help the readers to identify in a better way.

During the development of an efficient review protocol, a particular list of items must be taken into account to focus on the PRISMA, and to get a clear view of the planned review process an extra detail will be more helpful in this process. Rather than the customary of the author, there is a need for more words or space in the PRISMA. Transparency and reproducibility will be available by giving more detailed information about that, and hence in the generated systematic report, the details mentioned must be limited by the authors, and if needed the summary of the report will be given and the finished protocol was referred by the readers or PROSPERO record. Following new journal rules aimed at encouraging reproducibility, this review proposes that full explanations of planned scientific details for systematic reviews are acceptable. There are several checklist elements to match how we picture them appearing in a procedure; publishing them in this order may help readers understand what's going on. If the authors feel that changing the order in which the checklist items appear is necessary, they should do so. In their protocol, authors must describe every PRISMA element.

Discussions

These discussions made use of selected articles as described in the above section. After duplicates were removed from the 80 titles and database citations loaded, just 68 remained. After evaluating the titles and abstracts, 54 were found to be appropriate for full-text examination. Of the 54 papers considered eligible, 40 were eliminated because they were unrelated, lacked full texts, or were abstract-only articles. As a result, 14 publications out of 80 were found to meet the meta-analysis’ inclusion criteria.

Original research articles were cross-sectional studies like comparative studies, random controlled trials, clinical trials, review papers, systemic reviews, and meta-analyses. Table 1 represents the effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Psychological Health in Sports. The table illustrates the sample of respondents, variables used for the evaluation and outcomes achieved for the respective studies.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide challenge. Meier et al . [ 61 ] reported administrations of countries and public health organizations take action most effective commendation to restrict contamination is social distancing. Further, various countries opted for mandatory lockdowns and the closing of public areas for maintaining social distancing. A greater level of mental distress was discovered as a result of changing to new protective measures, according to [ 62 ]'s research on the effects of the coronavirus outbreak on public health. Further, due to this outbreak there are severe mental health disorders like increases in fear, anxiety and depression, gambling problems, sleep and eating disorders, psychological rigidity, obsessive–compulsive disorder, family conflicts, fitness concerns, sedentary lifestyle and negative habits, low mood, large intake of alcohol and drugs, self-harm attempts or suicidal behaviour, and rumination [ 13 , 51 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 ] respectively.

Due to the new standards of a pandemic, the athletes have gone through huge changes in their style of living and daily activities, communal relationships, financial-related issues, and loss of goals and satisfaction. In line with these challenges, psychological well-being cannot be isolated from both the physical and mental problems manifestations and related fundamental issues in which the outer injury and recovery may take a long time. Peluso et al . [ 71 ] stated that physical activity has valuable impacts on the control and treatment of various diseases and mental illnesses like depression and anxiety. Further, stress and physical activity effectively affect the factors which influence cardiovascular status [ 72 ]. According to De Matos et al . [ 73 ] the normal problems faced by athletes are physical training, heart diseases, and risk factors. Similarly, during the Coronavirus lockdown, athletes trained less frequently and for shorter periods, which can cause higher depression, anxiety, and stress scores. In addition, [ 74 ] reported that excessively low training load may affect psycho-social engagement among athletes by inducing training-induced physiological and physiological adaptation to aversive preparedness.

Further, McGuine et al . [ 52 ] reported less physical activity and lower quality of life due to school closures and sports cancellations during a pandemic in the USA, and for women players and team sports players’ fewer symptoms like anxiety and depression were faced. Similarly, [ 54 ] also stated that a survey before and after one month of school closure due to the pandemic reported less dissolution of their athletic identity and there is more support from the social environment and the communication between the team members is also increased. Moreover, due to the low quality of sleep and long periods of sleep, they were reported in Spanish handball players due to the decreased training intensity and volume during the pandemic period. Additionally, [ 75 ] mentioned that the numerous physical performance tests of soccer players were get affected in Brazil due to 63 days of quarantine which they conduct during their normal off-season. Furthermore, Haan et al . [ 76 ] reported in their study that Sweden athletes (elite football, ice hockey, and handball players) are concerned about their sport and their careers during this COVID crisis, along with the negative psychological impact of the pandemic.

Furthermore, during this pandemic situation, some players feel lonely and their psychological health gets affected [ 77 ]. Additional factors that have contributed to players' mental suffering include their exclusion from the athletic community, decreased training and activity, a lack of formal coaching, and a lack of social support from fans and the media [ 53 ]. Furthermore, depression, anxiety, and higher athletic identity symptoms were reported in individual and team sports athletes of Turkey and Italy during the lockdown period [ 47 , 73 ] and Uroh and Adewunmi . [ 60 ] also found that single players were more distressed rather than team players during the coronavirus pandemic. Similarly, [ 56 ] stated the negative effect of lockdown on the psychological health and life spheres among youth athletes in Spain. Likewise, individual athletes are more prone to psychological distress than team sports athletes [ 46 , 78 , 79 ]. Individual athletes are at a greater risk because in individual sports athletes are the only responsible person for their success or failure, they cannot get any support from anyone during the competition so they need to work accordingly. Thus, the present circumstance makes individual players more prone to psychological distress in compression to team sports athletes [ 80 , 81 , 82 ]. Additionally, a group of elite and semi-elite athletes from 15 different sports namely soccer, hockey, rugby, cricket, athletics, netball, basketball, endurance running, cycling, track and field, swimming, squash, golf, tennis, and karate in South Africa were examined by Pillay et al. in [ 55 ] to determine the psychological effects of the disease outbreak on their physical, nutritional, and mental health.

Although the outcomes in this study are from various sports, and geographical regions but results were reported the same from every region Athletes are suffering from mental health as well as physical challenges due to the compulsory restrictions and guidelines of this COVID-19 pandemic and during the COVID-19 outbreaks the athletes needed psychosocial services.

COVID-19 impacts on sports and athletes

Several influences were faced by the athletes and players who have long been preparing for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. For some people, no chance is given because of immediate retirement and due to the announcement of a postponement. For instance, British rowing squad member and two-time Olympic medalist Tom Ransley announced his retirement. Eddie Dawkins, who won the silver medal in the Olympics in Rio, recently declared his retirement from the game of track cycling. However, this opportunity is used by others to continue their performance or heal from any injuries they may have experienced the temporal shift in time and rapid modification to optimise their peak. As a consequence, enthusiastic and good attitudes were maintained by the sports players [ 83 ].

Due to the loss of daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly routines, the mental and outer health of the players gets affected. Many athletes lost their normal training routines when the terrible disaster struck in 2011, but the damage was still limited. Athletes carried out their training since many areas of Japan were sufficiently separated from the Fukushima prefecture without the unidentifiable effects of nuclear power plant accidents. The outbreak of COVID-19 has prompted players to stay at home in addition to forcing practically the training centre to be closed. In the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games along with other games, the qualified tournaments get cancelled which was impacted by social distancing measures implemented to prevent the spread of COVID-19. To make it more difficult to achieve a specific goal, these changes have enhanced feelings of doubt, perplexity, and frustration. The athletes work out for a long period due to the impact of practice sessions because there is no way to leave the house and engage in deep and systematic training. Due to this, there may increase in injuries, which in turn could make players feel even more doubt and frustration. Athletes may have increased anxiety due to less communication with their teammates, coaches, and other people.