51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

Constructive feedback is feedback that helps students learn and grow.

Even though it highlights students’ weaknesses, it is not negative feedback because it has a purpose. It is designed to help them identify areas for improvement.

It serves both as an example of positive reinforcement and a reminder that there is always room for further improvement. Studies show that students generally like feedback that points them in the right direction and helps them to improve. It can also increase motivation for students.

Why Give Constructive Feedback?

Constructive feedback is given to help students improve. It can help people develop a growth mindset by helping them understand what they need to do to improve.

It can also help people to see that their efforts are paying off and that they can continue to grow and improve with continued effort.

Additionally, constructive feedback helps people to feel supported and motivated to keep working hard. It shows that we believe in their ability to grow and succeed and that we are willing to help them along the way.

How to Give Constructive Feedback

Generally, when giving feedback, it’s best to:

- Make your feedback specific to the student’s work

- Point out areas where the student showed effort and where they did well

- Offer clear examples of how to improve

- Be positive about the student’s prospects if they put in the hard work to improve

- Encourage the student to ask questions if they don’t understand your feedback

Furthermore, it is best to follow up with students to see if they have managed to implement the feedback provided.

General Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

The below examples are general templates that need to be edited so they are specific to the student’s work.

1. You are on the right track. By starting to study for the exam earlier, you may be able to retain more knowledge on exam day.

2. I have seen your improvement over time. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

3. You have improved a lot and should start to look towards taking on harder tasks for the future to achieve more self-development.

4. You have potential and should work on your weaknesses to achieve better outcomes. One area for improvement is…

5. Keep up the good work! You will see better results in the future if you make the effort to attend our study groups more regularly.

6. You are doing well, but there is always room for improvement. Try these tips to get better results: …

7. You have made some good progress, but it would be good to see you focusing harder on the assignment question so you don’t misinterpret it next time.

8. Your efforts are commendable, but you could still do better if you provide more specific examples in your explanations.

9. You have done well so far, but don’t become complacent – there is always room for improvement! I have noticed several errors in your notes, including…

10. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results. It would be good to see you editing your work to remove the small errors creeping into your work…

11. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. One area for improvement is your tone of voice, which sometimes comes across too soft. Don’t be afraid to project your voice next time.

12. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

13. Your efforts are commendable, but it would have been good to have seen you focus throughout as your performance waned towards the end of the session.

15. While your work is good, I feel you are becoming complacent – keep looking for ways to improve. For example, it would be good to see you concentrating harder on providing critique of the ideas explored in the class.

16. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results! Try to improve your handwriting by slowing down and focusing on every single letter.

17. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. Keep up the good work and you will see your grades slowly grow more and more. I’d like to see you improving your vocabulary for future pieces.

18. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

19. You have potential and should work on your using more appropriate sources to achieve better outcomes. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

Constructive Feedback for an Essay

1. Your writing style is good but you need to use more academic references in your paragraphs.

2. While you have reached the required word count, it would be good to focus on making sure every paragraph addresses the essay question.

3. You have a good structure for your essay, but you could improve your grammar and spelling.

4. You have made some good points, but you could develop them further by using more examples.

5. Your essay is well-written, but it would be helpful to provide more analysis of the topic.

6. You have answered the question well, but you could improve your writing style by being more concise.

7. Excellent job! You have covered all the key points and your writing is clear and concise.

8. There are a few errors in your essay, but overall it is well-written and easy to understand.

9. There are some mistakes in terms of grammar and spelling, but you have some good ideas worth expanding on.

10. Your essay is well-written, but it needs more development in terms of academic research and evidence.

11. You have done a great job with what you wrote, but you missed a key part of the essay question.

12. The examples you used were interesting, but you could have elaborated more on their relevance to the essay.

13. There are a few errors in terms of grammar and spelling, but your essay is overall well-constructed.

14. Your essay is easy to understand and covers all the key points, but you could use more evaluative language to strengthen your argument.

15. You have provided a good thesis statement , but the examples seem overly theoretical. Are there some practical examples that you could provide?

Constructive Feedback for Student Reports

1. You have worked very hard this semester. Next semester, work on being more consistent with your homework.

2. You have improved a lot this semester, but you need to focus on not procrastinating.

3. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could improve your grades by paying more attention in class and completing all your homework.

4. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could still improve your grades by studying more and asking for help when you don’t understand something.

5. You have shown great improvement this semester, keep up the good work! However, you might want to focus on improving your test scores by practicing more.

6. You have made some good progress this semester, but you need to continue working hard if you want to get good grades next year when the standards will rise again.

7. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework on time and paying more attention in class.

8. You have worked hard this semester, but you could still improve your grades by taking your time rather than racing through the work.

9. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework in advance so you have time to check it over before submission.

10. While you usually understand the instructions, don’t forget to ask for help when you don’t understand something rather than guessing.

11. You have shown great improvement this semester, but you need to focus some more on being self-motivated rather than relying on me to keep you on task.

Constructive feedback on Homework

1. While most of your homework is great, you missed a few points in your rush to complete it. Next time, slow down and make sure your work is thorough.

2. You put a lot of effort into your homework, and it shows. However, make sure to proofread your work for grammar and spelling mistakes.

3. You did a great job on this assignment, but try to be more concise in your writing for future assignments.

4. This homework is well-done, but you could have benefited from more time spent on research.

5. You have a good understanding of the material, but try to use more examples in your future assignments.

6. You completed the assignment on time and with great accuracy. I noticed you didn’t do the extension tasks. I’d like to see you challenging yourself in the future.

Related Articles

- Examples of Feedback for Teachers

- 75 Formative Assessment Examples

Giving and receiving feedback is an important part of any learning process. All feedback needs to not only grade work, but give advice on next steps so students can learn to be lifelong learners. By providing constructive feedback, we can help our students to iteratively improve over time. It can be challenging to provide useful feedback, but by following the simple guidelines and examples outlined in this article, I hope you can provide comments that are helpful and meaningful.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is IQ? (Intelligence Quotient)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

2 thoughts on “51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students”

Very helpful to see so much great developmental feedback with so many different examples.

Great examples of constructive feedback, also has reinforced on the current approach i take.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

16 constructive feedback examples — and tips for how to use them

Giving constructive feedback is nerve-wracking for many people. But feedback is also necessary for thriving in the workplace.

It helps people flex and grow into new skills, capabilities, and roles. It creates more positive and productive relationships between employees. And it helps to reach goals and drive business value.

But feedback is a two-way street. More often than not, it’s likely every employee will have to give constructive feedback in their careers. That’s why it’s helpful to have constructive feedback examples to leverage for the right situation.

We know employees want feedback. But one study found that people want feedback if they’re on the receiving end . In fact, in every case, participants rated their desire for feedback higher as the receiver. While the fear of feedback is very real, it’s important to not shy away from constructive feedback opportunities. After all, it could be the difference between a flailing and thriving team.

If you’re trying to overcome your fear of providing feedback, we’ve compiled a list of 16 constructive feedback examples for you to use. We’ll also share some best practices on how to give effective feedback .

What is constructive feedback?

When you hear the word feedback, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? What feelings do you have associated with feedback? Oftentimes, feedback conversations are anxiety-ridden because it’s assumed to be negative feedback. Unfortunately, feedback has this binary stigma, it’s either good or bad.

But in reality, there are plenty of types of feedback leveraged in both personal and professional relationships. They don’t all fall into one camp or the other. And each type of feedback is serving a purpose to ultimately better an individual, team, or work environment.

For example, positive feedback can be used to reinforce desired behaviors or big accomplishments. Real-time feedback is reserved for those “in the moment” situations. Like if I’ve made a mistake or a typo in a blog, I’d want my teammates to give me real-time feedback .

However, constructive feedback is its own ball game.

What is constructive feedback?

Constructive feedback is a supportive way to improve areas of opportunity for an individual person, team, relationship, or environment. In many ways, constructive feedback is a combination of constructive criticism paired with coaching skills.

16 constructive feedback examples to use

To truly invest in building a feedback culture , your employees need to feel comfortable giving feedback. After all, organizations are people, which means we’re all human. We make mistakes but we’re all capable of growth and development. And most importantly, everyone everywhere should be able to live with more purpose, clarity, and passion.

But we won’t unlock everyone’s full potential unless your people are comfortable giving feedback. Some employee feedback might be easier to give than others, like ways to improve a presentation.

But sometimes, constructive feedback can be tricky, like managing conflict between team members or addressing negative behavior. As any leader will tell you, it’s critical to address negative behaviors and redirect them to positive outcomes. Letting toxic behavior go unchecked can lead to issues with employee engagement , company culture, and overall, your business’s bottom line.

Regardless of where on the feedback spectrum your organization falls, having concrete examples will help set up your people for success. Let’s talk through some examples of constructive feedback. For any of these themes, it’s always good to have specific examples handy to help reinforce the feedback you’re giving. We’ll also give some sample scenarios of when these phrases might be most impactful and appropriate.

Constructive feedback examples about communication skills

An employee speaks over others and interrupts in team meetings.

“I’ve noticed you can cut off team members or interrupt others. You share plenty of good ideas and do good work. To share some communication feedback , I’d love to see how you can support others in voicing their own ideas in our team meetings.”

An employee who doesn’t speak up or share ideas in team meetings.

“I’ve noticed that you don’t often share ideas in big meetings. But in our one-on-one meetings , you come up with plenty of meaningful and creative ideas to help solve problems. What can I do to help make you more comfortable speaking up in front of the team?”

An employee who is brutally honest and blunt.

“Last week, I noticed you told a teammate that their work wasn’t useful to you. It might be true that their work isn’t contributing to your work, but there’s other work being spread across the team that will help us reach our organizational goals. I’d love to work with you on ways to improve your communication skills to help build your feedback skills, too. Would you be interested in pursuing some professional development opportunities?”

An employee who has trouble building rapport because of poor communication skills in customer and prospect meetings.

“I’ve noticed you dive right into the presentation with our customer and prospect meetings. To build a relationship and rapport, it’s good to make sure we’re getting to know everyone as people. Why don’t you try learning more about their work, priorities, and life outside of the office in our next meeting?”

Constructive feedback examples about collaboration

An employee who doesn’t hold to their commitments on group or team projects.

“I noticed I asked you for a deliverable on this key project by the end of last week. I still haven’t received this deliverable and wanted to follow up. If a deadline doesn’t work well with your bandwidth, would you be able to check in with me? I’d love to get a good idea of what you can commit to without overloading your workload.”

An employee who likes to gatekeep or protect their work, which hurts productivity and teamwork .

“Our teams have been working together on this cross-functional project for a couple of months. But yesterday, we learned that your team came across a roadblock last month that hasn’t been resolved. I’d love to be a partner to you if you hit any issues in reaching our goals. Would you be willing to share your project plan or help provide some more visibility into your team’s work? I think it would help us with problem-solving and preventing problems down the line.”

An employee who dominates a cross-functional project and doesn’t often accept new ways of doing things.

“I’ve noticed that two team members have voiced ideas that you have shut down. In the spirit of giving honest feedback, it feels like ideas or new solutions to problems aren’t welcome. Is there a way we could explore some of these ideas? I think it would help to show that we’re team players and want to encourage everyone’s contributions to this project.”

Constructive feedback examples about time management

An employee who is always late to morning meetings or one-on-ones.

“I’ve noticed that you’re often late to our morning meetings with the rest of the team. Sometimes, you’re late to our one-on-ones, too. Is there a way I can help you with building better time management skills ? Sometimes, the tardiness can come off like you don’t care about the meeting or the person you’re meeting with, which I know you don’t mean.”

A direct report who struggles to meet deadlines.

“Thanks for letting me know you’re running behind schedule and need an extension. I’ve noticed this is the third time you’ve asked for an extension in the past two weeks. In our next one-on-one, can you come up with a list of projects and the amount of time that you’re spending on each project? I wonder if we can see how you’re managing your time and identify efficiencies.”

An employee who continuously misses team meetings.

“I’ve noticed you haven’t been present at the last few team meetings. I wanted to check in to see how things are going. What do you have on your plate right now? I’m concerned you’re missing critical information that can help you in your role and your career.”

Constructive feedback examples about boundaries

A manager who expects the entire team to work on weekends.

“I’ve noticed you send us emails and project plans over the weekends. I put in a lot of hard work during the week, and won’t be able to answer your emails until the work week starts again. It’s important that I maintain my work-life balance to be able to perform my best.”

An employee who delegates work to other team members.

“I’ve noticed you’ve delegated some aspects of this project that fall into your scope of work. I have a full plate with my responsibilities in XYZ right now. But if you need assistance, it might be worth bringing up your workload to our manager.”

A direct report who is stressed about employee performance but is at risk of burning out.

“I know we have performance reviews coming up and I’ve noticed an increase in working hours for you. I hope you know that I recognize your work ethic but it’s important that you prioritize your work-life balance, too. We don’t want you to burn out.”

Constructive feedback examples about managing

A leader who is struggling with team members working together well in group settings.

“I’ve noticed your team’s scores on our employee engagement surveys. It seems like they don’t collaborate well or work well in group settings, given their feedback. Let’s work on building some leadership skills to help build trust within your team.”

A leader who is struggling to engage their remote team.

“In my last skip-levels with your team, I heard some feedback about the lack of connections . It sounds like some of your team members feel isolated, especially in this remote environment. Let’s work on ways we can put some virtual team-building activities together.”

A leader who is micromanaging , damaging employee morale.

“In the last employee engagement pulse survey, I took a look at the leadership feedback. It sounds like some of your employees feel that you micromanage them, which can damage trust and employee engagement. In our next one-on-one, let’s talk through some projects that you can step back from and delegate to one of your direct reports. We want to make sure employees on your team feel ownership and autonomy over their work.”

8 tips for providing constructive feedback

Asking for and receiving feedback isn’t an easy task.

But as we know, more people would prefer to receive feedback than give it. If giving constructive feedback feels daunting, we’ve rounded up eight tips to help ease your nerves. These best practices can help make sure you’re nailing your feedback delivery for optimal results, too.

Be clear and direct (without being brutally honest). Make sure you’re clear, concise, and direct. Dancing around the topic isn’t helpful for you or the person you’re giving feedback to.

Provide specific examples. Get really specific and cite recent examples. If you’re vague and high-level, the employee might not connect feedback with their actions.

Set goals for the behavior you’d like to see changed. If there’s a behavior that’s consistent, try setting a goal with your employee. For example, let’s say a team member dominates the conversation in team meetings. Could you set a goal for how many times they encourage other team members to speak and share their ideas?

Give time and space for clarifying questions. Constructive feedback can be hard to hear. It can also take some time to process. Make sure you give the person the time and space for questions and follow-up.

Know when to give feedback in person versus written communication. Some constructive feedback simply shouldn’t be put in an email or a Slack message. Know the right communication forum to deliver your feedback.

Check-in. Make an intentional effort to check in with the person on how they’re doing in the respective area of feedback. For example, let’s say you’ve given a teammate feedback on their presentation skills . Follow up on how they’ve invested in building their public speaking skills . Ask if you can help them practice before a big meeting or presentation.

Ask for feedback in return. Feedback can feel hierarchical and top-down sometimes. Make sure that you open the door to gather feedback in return from your employees.

Start giving effective constructive feedback

Meaningful feedback can be the difference between a flailing and thriving team. To create a feedback culture in your organization, constructive feedback is a necessary ingredient.

Think about the role of coaching to help build feedback muscles with your employees. With access to virtual coaching , you can make sure your employees are set up for success. BetterUp can help your workforce reach its full potential.

Elevate your communication skills

Unlock the power of clear and persuasive communication. Our coaches can guide you to build strong relationships and succeed in both personal and professional life.

Madeline Miles

Madeline is a writer, communicator, and storyteller who is passionate about using words to help drive positive change. She holds a bachelor's in English Creative Writing and Communication Studies and lives in Denver, Colorado. In her spare time, she's usually somewhere outside (preferably in the mountains) — and enjoys poetry and fiction.

5 types of feedback that make a difference (and how to use them)

Are you receptive to feedback follow this step-by-step guide, handle feedback like a boss and make it work for you, how to give constructive feedback as a manager, should you use the feedback sandwich 7 pros and cons, how to get feedback from your employees, why coworker feedback is so important and 5 ways to give it, feedback in communication: 5 areas to become a better communicator, how managers get upward feedback from their team, similar articles, 15 tips for your end-of-year reviews, how to give negative feedback to a manager, with examples, how to embrace constructive conflict, 25 performance review questions (and how to use them), how to give feedback to your boss: tips for getting started, how to give kudos at work. try these 5 examples to show appreciation, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Constructive criticism examples for students: how to give better feedback

Educators can harness the power of effective feedback to improve students’ learning outcomes . And constructive criticism is one approach that can help educators ensure their feedback hits the mark!

So, let’s explore examples of constructive criticism that are ideal for use with students and examine how this method can elevate classroom feedback.

What is constructive criticism?

Constructive criticism is a feedback method where educators target areas for improvement in students’ work, learning, or behavior. For constructive criticism to be considered helpful to students, it needs to embody these three main characteristics:

1. Constructive criticism is specific

Educators identify precise points for students to improve on.

2. Constructive criticism is actionable

Educators give students practical ways to address their points for improvement.

3. Constructive criticism is beneficial to students

Students understand exactly what to improve and the steps they need to take to achieve this, enabling them to progress.

Is constructive criticism considered positive or negative?

Originally, the word “criticism” had a neutral meaning — it simply described the process of making a judgment. However, the word has evolved to sometimes have negative connotations, such as when students criticize the amount of homework they receive.

Thus, if students perceive educator feedback as criticism, they may disengage from the feedback process and miss an opportunity for improvement.

To improve students’ perception of feedback, educators can reframe their advice using the constructive criticism examples featured below. These strategies facilitate educators in giving supportive, meaningful feedback that guides students toward achieving learning goals and outcomes.

Constructive criticism examples: ways to give better feedback to students

Here are some examples of ways you can give constructive criticism to students to help them reach their learning goals.

Use constructive criticism to identify students’ specific points for improvement

Educators can use constructive criticism to pinpoint specific areas for students to target and guide them on how to improve. This is more helpful than vague praise, such as “Well done!” or general comments such as “Improve this section.”

Vague praise could leave students unaware of what exactly they have done correctly or the specific areas they need to improve, resulting in missed learning opportunities.

How to implement this: Use the START (Situation, Task, Action, Result, and Transform) framework

- The START framework helps educators structure constructive criticism to give students a clear understanding of their next steps in learning — and how to tackle them.

- The educator reminds the student of the situation and/or task , identifies the student’s specific action within it, and describes the resulting outcome. This helps pinpoint the student’s exact area for development.

- Then, the educator explains strategies that will enable the student to transform the outcome, making the process constructive.

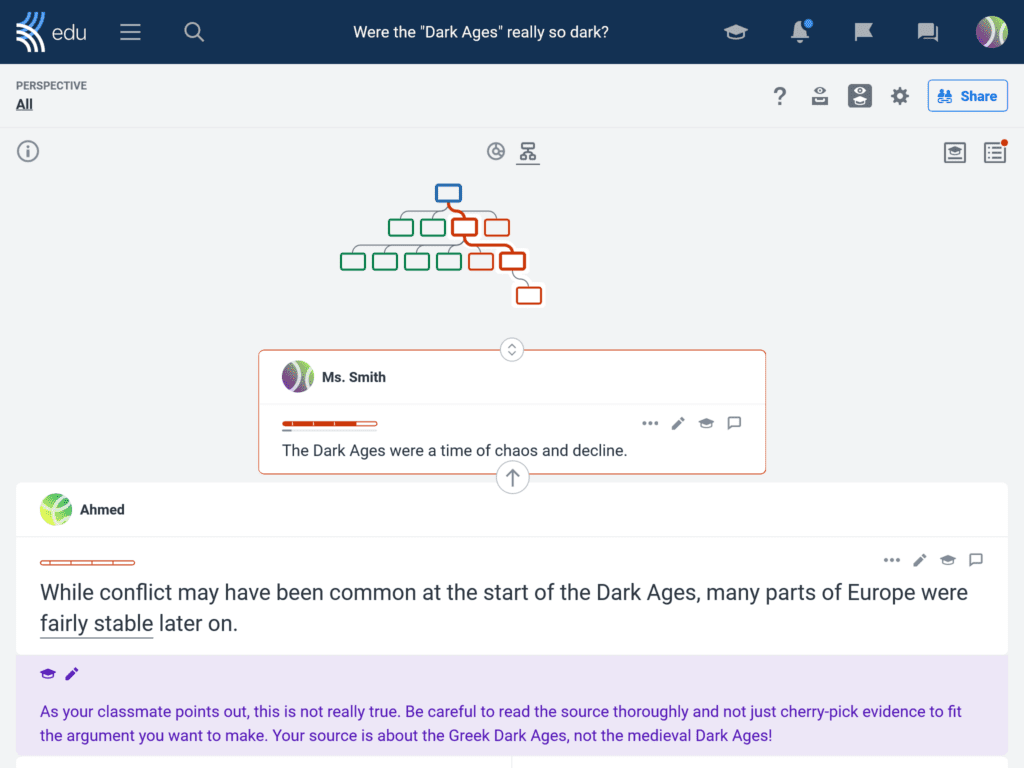

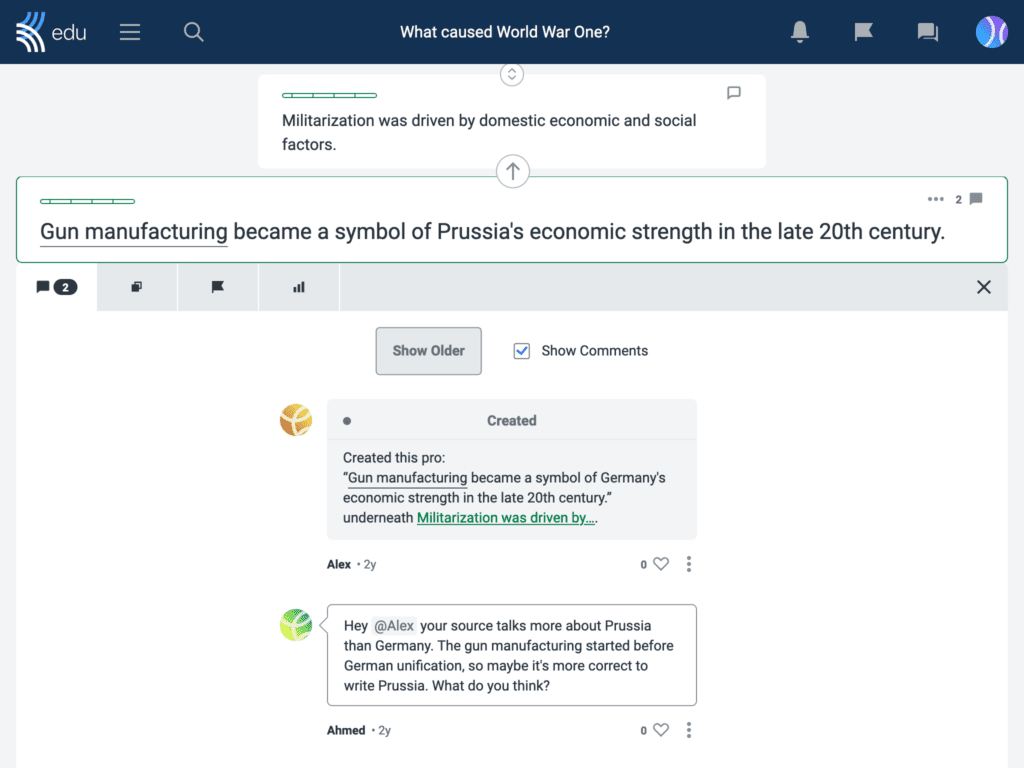

On Kialo Edu, you can give targeted feedback on every claim that students create, so students understand exactly what they need to improve.

Use constructive criticism to depersonalize feedback to students

Educators can use constructive criticism to emphasize feedback that targets specific work, learning, or behavior, rather than the student personally. This can promote positive and respectful feedback conversations with students, particularly those who sometimes perceive educator feedback as devastating personal criticism.

How to implement this: Use the Third Point method

- In the Third Point method, two people in the feedback conversation, in this case the educator and student, physically focus their attention on the third point. This should be a tangible item like the student’s work, an assessment rubric, or a behavior report.

- Focusing on the third point limits eye contact between the educator and student, which reduces their emotional involvement in the feedback process.

- The student is thus less likely to take the feedback personally and will be more receptive to acting on the educator’s advice.

If you’ve used a Kialo discussion as an activity with your students, consider using its argument map as a tangible third point to focus on when depersonalizing constructive criticism conversations with students.

Use constructive criticism as part of reflective dialogue with students

Educators can use reflective dialogue to encourage students to positively engage with constructive criticism. In these reflective dialogues, students have a space to share their perspectives on learning, with educators adjusting feedback based on the students’ viewpoints. This combats the negativity that students sometimes feel when they view feedback as an imposition that doesn’t consider their opinion.

How to implement this: Use the GROW (Goals, Reality, Options, and Will) framework

- Educators can use The GROW framework to structure constructive criticism during reflective dialogues.

- The educator and student begin by reviewing the learning goal and exploring the student’s current reality . Here, the student shares their perspective.

- The process becomes constructive as the educator and student generate options to help the student achieve the goal.

- They use these options to finalize the student’s next steps and agree on the support the educator will provide.

Use constructive criticism to immediately address students’ misconceptions

Educators can use constructive criticism when teaching content to promptly address students’ learning misconceptions. Students can then take immediate action to improve their learning. This can prevent students from repeating mistakes and embedding misconceptions throughout their work.

How to implement this: Use the Feedforward method

- With the Feedforward method, the educator plays a dynamic role, offering on-the-spot constructive criticism to students during lessons.

- The educator circulates among the class or target group, identifying points for students to address, providing them with constructive support, and monitoring their improvements.

- By the end of the session, students have made progress — and teachers have a bank of evidence ideal for formative assessment.

During a Kialo discussion, you can set feedback for students to appear in real-time for students to consider and implement as they work through their claims.

Train students to use constructive criticism for peer feedback

Training students to give constructive criticism develops their understanding of the feedback process to help each other progress. Moreover, it allows students a perspective into the educator feedback process, which may improve students’ outlook on engaging with the feedback they receive.

How do to implement this: Regularly use peer-to-peer feedback for assignments

- Educators can focus students’ feedback to each other by providing a clear list of success criteria for all tasks.

- You can also give students sentence starters (“Have you considered…?” or “One way you could improve this is…”) to help frame their constructive criticism.

- Following these preparations, students then work in pairs to provide reciprocal constructive criticism and address issues collaboratively.

- During peer conversations, educators monitor and offer support to develop students’ insight into the educator feedback process.

On Kialo Edu, students can give constructive criticism to their peers by leaving comments on claims. Teachers can also add their own comments to support this process, modeling how to leave appropriate constructive criticism.

We hope that our constructive criticism examples for students — and the time-saving tools in Kialo discussions — help you to maximize the benefits of supportive, meaningful feedback in your classroom.

And we practice what we preach here at Kialo Edu, so we’d love to hear your feedback! Head to our Topic Library to start a discussion with your students, and test out our time-saving teacher tools. Send your thoughts to [email protected] , or post them on any of our social media channels.

Want to try Kialo Edu with your class?

Sign up for free and use Kialo Edu to have thoughtful classroom discussions and train students’ argumentation and critical thinking skills.

How to Give Feedback

Why is feedback important?

Feedback has been known to be an important part of the learning process. Especially when coupled with deliberate practice, feedback can help students spend their time mastering aspects that they need to focus on most rather than practicing what they already know. Effective feedback works as a map to guide students by letting them know where they are now and what to work on in order to get to their goal. Without good feedback, students may carry misconceptions that they did not even realize they had while learning the material and walk aimlessly towards a goal without being sure how they can get there.

What constitutes effective feedback?

Effective feedback is: 1) targeted, 2) communicates progress, 3) timely, and 4) gives students the opportunity to practice and implement the feedback received. In a broader sense, these aspects relate to thinking about where the student is going, how the student is doing now, and what the next step is.

Targeted feedback

When giving feedback, it is important to make sure that it is specific and linked to clearly articulated goals or learning outcomes. Targeted feedback gives students an idea of what they did well and how they can improve in relation to the learning criteria stated in the course. Connecting feedback to specific and achievable goals helps provide students with an understanding of desired outcomes and sub goals as well. Additionally, goals should not be too challenging or too easy; goals that are too challenging can discourage students and make them feel unable to succeed, while goals that are too easy may not appropriately push students to improve and also provide them with unrealistic expectations of success.

Targeted feedback also includes prioritizing feedback – in other words, it is important not to overwhelm students with too many comments. Research has shown that even minimal feedback on students’ writing can lead to an improved second draft, especially in the early stages, because it lets students know if they are on the right track and whether readers understand their message. To implement this, you may consider setting up milestones in order to break up a class project or paper and provide feedback to students along the way.

Communicates progress

Feedback showing how far a student has come can help by providing students with information on how much they have improved and where they should direct more attention to. Studies have shown that formative, process-oriented feedback that is focused on accomplishments is more effective than summative feedback, such as letter grades, and also leads to greater interest in the class material. One strategy to consider may be providing specific comments on student work without a letter or number grade; students tend to fixate on such summative feedback, and studies have shown that providing both feedback and a grade actually negates the benefits of the given feedback.

Opportunity to practice

Simply giving targeted feedback will not be effective if students are not also given the chance to practice and put this feedback into place. Targeted feedback helps direct students’ efforts to focus on how they should move forward for the future, but practice allows students to actually learn from feedback by applying it. Otherwise, there is the potential for students to not actually digest the feedback even if they willingly received it. Some ways to link practice with targeted feedback are to have a series of related assignments where students are asked to incorporate feedback into each subsequent assignment, or create sub-goals within projects where students receive feedback on rough drafts along the way and are specifically given a goal to address the feedback in final drafts. Regardless of the nature of the assignment, the key part is that students be given the opportunity to implement the feedback they are given in related class assignments.

Timing of feedback

It is also important that feedback be timely. Generally, immediate feedback and more frequent feedback is often best so that students are on track for their goals, but timely feedback may not necessarily be given right away. The timing of feedback largely depends on the learning goals – immediate feedback is better when students are learning new knowledge, but slightly delayed feedback can actually be helpful when students are applying learned knowledge. In particular, if the learning goal of an assignment is for students to be able to not only master a skill but also recognize their own errors, then delayed feedback would be the most appropriate because it allows students to think about their mistakes and have the chance to catch their errors rather than relying on feedback to tell them.

For STEM classes, immediate feedback may include in-class concept questions where students can know right away whether they have understood the new material that they just learned, while delayed feedback would include a problem set where they have to apply these learned concepts and wait before receiving feedback. For non-STEM classes, immediate feedback may include an in-class discussion, where students can hear feedback and thoughts on their ideas in real time, while an example of delayed feedback would be an essay, where students have to apply what they have learned in class to their writing and do not receive feedback on their submission right away.

Strategies to implement feedback in the classroom

As an instructor, you may not always have the time to provide feedback the way you would like to. The following strategies offer some suggestions for how you can still efficiently provide students with useful feedback.

Look for common errors among the class

You may notice common errors or misconceptions among the class while grading exams, or realize that many students ask a similar question at office hours. If you take note of these common mistakes, you can then address them to the class as a whole. This can have the added benefit of making students feel less alone, as some may not realize that the mistake they made is a common one among their peers.

Prioritize feedback

As mentioned earlier, it can be helpful even to provide minimal feedback on a rough draft to steer students in the right direction. Often, it might not be necessary to provide feedback on all aspects of an assignment and doing so may actually overwhelm students with feedback. Instead, think about what would be most important to provide feedback on at this time – you may consider providing feedback on one area at a time, such as one step of crafting an argument or one step of solving a problem. Be sure to communicate with students which areas you did/did not provide feedback on.

Incorporate real-time group feedback.

Many feedback strategies appear more feasible for small classes, but this method is particularly useful in large lecture classes. Clicker questions are a common example of real time group feedback. It can be particularly difficult in larger classes to gain a good picture of student comprehension, so real-time feedback through clicker questions and polls can allow you to check in with the class. For instance, if you notice there are a large proportion of incorrect answers, you can think about how to present the material in a different way or have students discuss the problem together before re-polling. Other options for real-time group feedback include external polling apps – the most commonly used polling apps on campus are PollEverywhere , Socrative , and Sli.do .

Utilize peer feedback

It may not be logistically feasible for you to provide feedback to your students as often as you wish. Consider what opportunities for peer feedback may exist in your subject. For example, students could provide each other with immediate, informal feedback in-class using techniques such as “Think-Pair” where each student has had time to first grapple with a concept or a problem individually and then is asked to explain the concept or problem solving approach to each other. Using peer feedback allows students to learn from each other while also preventing you from getting overwhelmed with constantly having to provide feedback as the instructor. Peer feedback can be just as valuable as instructor feedback when students are clear on the purpose of peer feedback and how they can effectively engage in it. One way to create successful peer feedback, particularly for more substantial assignments, is to provide students with a rubric and an example that is evaluated based on the rubric. This makes it clear to students what they should be looking for when conducting peer feedback, and what constitutes a successful or unsuccessful end result.

Create opportunities for students to reflect on feedback

By reflecting on how they will implement the feedback they have received, students are able to actively interact with the feedback and connect it to their work. For example, if students have a class project divided into milestones, you may ask students to write a few sentences about how they used the comments they received and how it impacted the subsequent assignment.

Ambrose, Susan A., Michael W. Bridges, Michele DiPietro, Marsha C. Lovett, and Marie K. Norman (2010). “What kinds of practice and feedback enhance learning?” In How Learning Works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching (pp. 121–152). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Benassi, V. A., Overson, C. E., & Hakala, C. M. (2014). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/ index.php

Goodwin, Bryan and Miller, Kirsten (2012). “Good Feedback is Targeted, Specific, Timely”. Educational Leadership: Feedback for Learning , Vol. 70, No. 1.

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Feedback for Learning

Feedback and revision are important parts of any learning experience. From in-class activities and assignments, to peer-reviewed manuscripts, feedback is essential for growth and learning. And yet, if students don’t reflect on or apply notes or comments, it can sometimes feel like feedback doesn’t matter all that much. Giving feedback can feel like an arduous process, and when it goes unused on student assignments, it can leave instructors feeling frustrated. This resource offers strategies to make giving feedback easier and more effective. While there are specific technologies (discussed below) that can help facilitate feedback in an online or hybrid/HyFlex learning environment, the strategies presented here are applicable to any kind of course (e.g.: large lecture, seminar) and across any modality (e.g.: synchronous, asynchronous, fully online, hybrid, or in-person).

On this page:

- Feedback for Learning: What and Why

- Characteristics of Effective Feedback

- Strategies for Giving Effective Feedback

- Facilitating Feedback with Columbia-Supported Technologies

Reflecting on Your Feedback Practices

- Resources & References

The CTL is here to help!

Seeking additional support with enhancing your feedback practices? Email [email protected] to schedule a 1-1 consultation. For support with any of the Columbia tools discussed below, email [email protected] or join our virtual office hours .

Interested in inviting the CTL to facilitate a session on this topic for your school, department, or program? Visit our Workshops To Go page for more information.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Feedback for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/feedback-for-learning/

Feedback for Learning: What and Why

What is feedback and why does it matter .

Broadly defined, feedback is “information given to students about their performance that guides future behavior” (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 125). Feedback can help set a path for students, directing their attention to areas for growth and improvement, and connecting them with future learning opportunities. At the same time, there is an evaluative component to feedback, regardless of whether it is given with a grade. Effective feedback tells students “ what they are or are not understanding, where their performance is going well or poorly, and how they should direct their subsequent efforts” (Ambrose et al., 2010, p. 137). In this way, feedback is essential to students’ learning and growth.

It is not enough for students to receive feedback. They also need explicit opportunities to implement and practice with the feedback received. In their How Learning Works: Seven Research-based Principles for Smart Teaching , Ambrose et al. (2010) underscore the importance of feedback, coupled with opportunities for practice: “Goal-directed practice coupled with targeted feedback are critical to learning ” (p. 125, emphasis in original). They further highlight the interconnection of feedback, practice, and performance in relation to overarching course goals.

Types of Feedback

There is no one size fits all for feedback. While there are common characteristics of effective feedback (discussed further in the following section), the form it takes will change across contexts. It can also come at different points of time during an assignment. You might offer students backward-looking feedback on a final product, after a student has “done” something; this type of feedback is usually given alongside an assignment grade. Or, you might offer forward-looking feedback, providing students advice and suggestions while the work is still in progress. It can be helpful for students to receive both kinds of feedback, with opportunities for implementation throughout. Related, the kinds of questions or prompts you use in your feedback will vary based on the kinds of responses and revisions you’re trying to solicit from students. Types of feedback may include: corrective, epistemic, suggestive, and epistemic + suggestive (Leibold and Schwarz, 2015).

These particular types of feedback are not exclusive of each other. It’s very common that the feedback you give will have elements of some, if not all, of these four types. What type you use at what point will depend on the goals of the assignment, as well as the goal of the feedback and the kinds of revision and responses you are trying to solicit.

Characteristics of Effective Feedback

Effective feedback is:

- Targeted and Concise: Too much feedback can be overwhelming; it can be difficult to know where to begin revising and where to prioritize one’s efforts. Use feedback to direct students’ attention to the main areas where they are likely to make progress; identify 2-3 main areas for improvement and growth.

- Focused: To help prioritize the main areas you identify, align your feedback with the goals of the assignment. You might also consider what other opportunities students have had or will have to practice these skills.

- Action-Oriented: Offer feedback that guides students through the revision process. Be direct and point to specific areas within the student’s work, offering suggestions for revision to help direct their efforts.

- Timely: Feedback is most useful when there is time to implement and learn from it. Offer frequent feedback opportunities ahead of a final due date (forward-looking feedback), allowing students to engage with your feedback and use it throughout their revision process. These opportunities for practice will help students develop further mastery of course material.

Strategies for Giving Effective Feedback

This section offers strategies for putting the characteristics of effective feedback into action. These strategies are applicable across class types (e.g.: large lecture, seminar) and modalities (e.g.: in-person, fully online, hybrid/HyFlex).

Create a culture of feedback

Establish a respectful and positive learning climate where feedback is normalized and valued. This includes helping students see the value of feedback to their learning, and acknowledging the role that mistakes, practice, and revision play in learning. Offer students frequent opportunities to receive feedback on their work in the course. Likewise, offer frequent opportunities for students to give f eedback on the course. This reciprocal feedback process will help to underscore the importance and value of feedback, further normalizing the process. For support on collecting student feedback, see the CTL’s Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback resource.

Partner with your students

As McKeachie writes in McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers (2011) , “Effective feedback is a partnership; it requires actions by the student as well as the teacher” (p. 108). It’s not enough for you to just give feedback; students need to be involved throughout the process. You might engage students in a meta discussion, soliciting feedback about feedback. Engage students in conversations about what makes feedback most useful, its purpose and value to learning, and stress the importance of implementation.

You might also consider the role of peer review in the feedback process. While peer review should not replace instructor feedback, you can take into consideration the kinds of feedback students will have already received as you are reviewing their work. This can be particularly helpful for larger classes where multiple rounds of feedback from the instructor and/or TAs is not possible. For support on engaging students in peer review, see the CTL’s Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context resource.

Align your feedback with the learning objectives

When giving feedback, be sure that your comments and suggestions align with overall course objectives, as well as the goals of the assignment. One helpful way to be sure your feedback aligns with learning objectives is to have a rubric. A rubric is an assessment tool that “articulates the expectations for an assignment by listing the criteria or what counts, and describing levels of quality” (Malini Reddy & Andrade, 2010, p. 435). Rubrics help make the goals and purpose of the assignment explicit to students, while also helping you save time when giving feedback. They are typically composed of three sections: evaluation criteria (e.g.: assignment learning objectives, what students are being assessed on); assessment values (e.g.: “excellent, good, and poor,” letter grades, or a scale of 1-5, etc.); and a description of each assessment value (e.g.: a “B” assignment does this…). If using rubrics, you might consider co-constructing the rubric with your students based on the assignment prompt and goals. This can help students take more ownership of their learning, as well as provide further clarification of your expectations for the assignment.

Keep your feedback focused and simple

Keep in mind the key skills or competencies you hope students will practice and master in the particular assignment, and use those to guide your feedback. As John Bean writes in Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom (2011), “Because your purpose is to stimulate meaningful revision, your best strategy is to limit your commentary to a few problems that you want the student to tackle when preparing the next draft. It thus helps to establish a hierarchy of concerns, descending from higher-order issues (ideas, organization, development, and overall clarity) to lower-order issues (sentence correctness, style, mechanics, spelling, and so forth)” (p. 322). When considering your hierarchy of concerns, keep in mind the stage of the student’s draft: early drafts benefit more from higher-order feedback, as the specifics of the assignment may shift and change as the student continues drafting and revising. A later draft, closer to being “finished,” may benefit from lower-order concerns focusing on style and mechanics.

Consider the timing of your feedback

Be sure to offer multiple opportunities for feedback throughout the course; this frequency will also help support the culture of feedback discussed above. It’s also important that you consider when students will receive feedback from you, and what they will do with it; remember that, “if students are to learn from feedback, they must have opportunities to construct their own meaning from the received message: they must do something with it, analyze it, ask questions about it, discuss it with others and connect it with prior knowledge” (Nicol et al., 2014, p. 103). Give students time to implement your feedback whether to revise their work or apply it to future assignments.

Change up your mode of delivery

While the focus of feedback shifts depending on the assignment goals and your course context, you might also consider changing up the mode of your feedback delivery. Written comments, whether throughout the text or summarized at the end of the assignment, are valuable to students’ learning, but they are not the only way to deliver effective feedback:

- Audio/video feedback: To help save yourself time, and to humanize your feedback, consider using audio or visual feedback (Gannon, 2017; Cavanaugh and Song, 2014). Most instructors can talk through their ideas quicker than they can handwrite or type them, making audio feedback a timesaver. Audio feedback allows students to hear your tone and intended delivery. Audio/video feedback is particularly useful for fully online asynchronous courses, as it allows students an opportunity to connect with you, the instructor, on a more personal level than typed comments might provide .

1-1 meetings: Consider using your office hours or other scheduled meetings to talk with students 1-1 about their work. You might ask students to explain or paraphrase the feedback they received. Prompts can include: 1) What was the feedback?; 2) What did you learn from my feedback?; 3) Based on the feedback, how will you improve your work?

Small group meetings : If you have a larger class, you might consider creating feedback groups where students will have read each other’s work and peers can share their feedback alongside you in a small group synchronous meeting. (This method can work regardless of the assignment being a group project or an individual assignment.) If teaching a fully online or hybrid/HyFlex course, these meetings can be facilitated in a dedicated Zoom meeting, or during class time using Zoom breakout rooms.

Facilitating Feedback with Columbia-Supported Technologies

While there is no shortage of technologies to help facilitate effective feedback, as this Chronicle of Higher Education Advice Guide highlights, it’s recommended that you work with tools supported by Columbia. These tools come with the added benefit of University support, as well as a higher likelihood of student familiarity. The technology you choose should align with the goals of the assignment and feedback; remember, keep it simple. While these technologies can help facilitate feedback for face-to-face courses, they are particularly useful for those teaching in a fully online or hybrid/HyFlex modality.

For further support with setting up one of these platforms and making it work for your course context, please contact the Learning Designer liaison for your school to schedule a consultation, or drop in to our CTL Support Office Hours via Zoom.

CourseWorks (Canvas)

CourseWorks offers a number of built-in features that can help facilitate effective feedback, furthering your students’ growth and learning, and helping to save you time in the process. Note: some of these features require initial enabling on your CourseWorks page. For help setting up your CourseWorks page, and further information about CourseWorks features, visit the CTL’s Knowledge Base . The CTL also offers two self-paced courses: Intro to CourseWorks (Canvas) Online and Assessment and Grading in CourseWorks (Canvas) Online , as well as live workshops for Teaching Online with CourseWorks .

Gradebook Comments

If using the CourseWorks Gradebook, you can attach summative feedback comments for your students; this is especially helpful when offering backward-looking feedback on assignments already submitted. For help on adding general Gradebook comments, see the Canvas Help Documentation: How do I leave comments for students in the Gradebook? .

Quiz Tool Feedback

If you are using the CourseWorks quiz tool, you generate automated feedback for correct and/or incorrect responses. For correct responses, you might consider expanding upon the response, making connections across course materials. For an incorrect response, you might direct the student’s attention to particular course materials (e.g.: video, chapter in a textbook, etc.). For help with generating automated feedback in quizzes, see the Canvas Help Documentation: What options can I set in a quiz? .

As previously discussed, rubrics can be a great way to both align feedback with the goals of an assignment, and save time while giving feedback. You can create rubrics for your assignments within CourseWorks to further support this process. It is also possible to copy over and edit rubrics across assignments, which is particularly helpful when reviewing different drafts or components of the same assignment. For further support on creating and using rubrics in CourseWorks, see the Canvas Help Documentation: How do I add a rubric to an assignment? .

SpeedGrader

Within SpeedGrader , there are a number of ways to provide students with feedback. One key benefit of SpeedGrader is that it allows instructors to view, grade, and comment on student work without the need to download documents, which can greatly reduce the time needed to grade student work. Using the DocViewer , you can annotate within a student’s assignment using a range of commenting styles, including: in-text highlights and other edits, marginal comments, summative comments on large areas of an assignment, handwritten or drawing tools, and more. Comments can also be made anonymously.

You can also offer students holistic assignment comments ; these particular comments are not specific to any one part of the assignment, but rather, appear as a summary comment on the project as a whole. There are a number of options for the mode of these comments, including: a brief text comment, an attachment (e.g.: a Word doc or PDF), or an audio/video comment. There is also a space for students to leave a message in response to your feedback, which can encourage them to more deeply engage with, and reflect upon, your feedback. For more detailed instructions on using the different tools, please see the Canvas Help Documentation: How do I add annotated comments in student submissions?

Gradescope

Although Gradescope is more commonly used as an assessment and grading tool, there are a few features to support giving feedback; it is particularly useful when providing feedback on handwritten assignments submitted digitally, or on those assignments using particular software (e.g.: LaTex, other coding and programming languages, etc.). In Gradescope, you can provide comments and feedback using LaTex , making it easier to give feedback on assignments using mathematical equations or formulas. Gradescope also allows for in-text feedback and commenting using a digital pen or textbox ; this allows for feedback on hand-written assignments submitted digitally. For more Gradescope support, see the CTL’s Creating Assignments and Grading Online with Gradescope resource.

While Panopto is typically used for recording course videos and lectures, it can also be helpful for providing students with video walkthrough feedback of their assignments. Using Panopto, you can screencast your student’s assignment while also recording your audio feedback. This can help humanize your feedback, while also simulating a 1-1 conference or meeting with the student. An added benefit of using Panopto is that you can edit the recording before sharing it with your student (e.g.: removing pauses, rephrasing comments, etc.). For further support on getting started and using Panopto, see the CTL’s Teaching with Panopto resource.

Like Panopto, you can also use Zoom to record a feedback walkthrough. The one major difference is that Zoom recordings are done in a single take; there is no opportunity to edit the recording. Zoom is also great for meeting with students either 1-1 or in small groups. If using synchronous class time for small group feedback sessions, you can “circulate” between breakout rooms to check in with students and offer feedback. For further Zoom support, see the CTL’s Teaching with Zoom resource, or visit CUIT’s Zoom support page .

Reflecting back, can you tell if your past feedback practices were effective? Did your students understand and use the feedback you gave? Did their work improve as a result of the feedback given? What small changes to your feedback practices would benefit you and your students?

With an upcoming assignment in mind, reflect on the following questions to guide your future feedback practices:

- How can you make your feedback targeted and concise? Consider the biggest challenge to the student’s success in the assignment.

- What will be the focus of your feedback? Focus on the most important skills or competencies you hope students will gain from the assignment.

- What type of feedback will you give (corrective, epistemic, suggestive, epistemic and suggestive, some other combination)? Connect the type of feedback you offer to the goals of the feedback and revision.

- How much time will students have to implement your feedback and revise? If students only receive feedback on the final products (with or without a grade), how will you help them use this feedback on future assignments?

- How can the student implement your feedback? Suggest places for students to begin.

- When will students receive feedback? What would be most useful to help students implement your feedback and further practice these skills?

- What will be the mode of delivery for the feedback? What technologies will you use?

Resources & References

Ctl resources .

Creating Assignments and Grading Online with Gradescope

Peer Review: Intentional Design for Any Course Context

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., & Norman, M.K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching . Jossey-Bass.

Bean, J. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom, 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass.

Cavanaugh, A.J. & Song, L. (2014). Audio feedback versus written feedback: Instructors’ and students’ perspectives . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10 (1), 122-138.

Desrochers, C. G., Zell, D., & Torosyan, R. Provided meaningful feedback on students’ academic performance . The IDEA Center.

Fiock, H. & Garcia, H. (2019, November 11). How to give your students better feedback with technology advice guide . Chronicle of Higher Education.

Gannon, K. (2017, November 26). How to escape grading jail . Chronicle of Higher Education.

Leibold, N. & Schwarz, L. M. (2015). The art of giving online feedback . Journal of Effective Teaching. 15 (1), 34-46.

Malini Reddy, Y. & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 35 (4), 435-448.

McKeachie W.J. (2011). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers, 13th ed. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 39 (1), 102-122.

The CTL researches and experiments.

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning provides an array of resources and tools for instructional activities.

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Constructive feedback

Ivan Andreev

Demand Generation & Capture Strategist, Valamis

December 19, 2021 · updated April 3, 2024

14 minute read

December 19, 2021

The aim of this article is to provide you with a clear idea of what constructive feedback is and how it fits into the workplace.

Constructive feedback is a useful tool that managers and employees can engage in to improve the standard of work. There is a right way to give good constructive feedback which you will learn by the end of this page.

What is constructive feedback?

30 constructive feedback examples, how to give constructive feedback, 10 tips to help your feedback make a positive impact.

By engaging your employees with constructive feedback you create an atmosphere that nurtures support and growth.

Proper feedback has a knock-on effect on loyalty, work ethic , performance, and growth for individuals and teams.

Feedback can be given in multiple ways so take a look at our guide “ types of feedback .” You can learn how to take negative feedback and turn it into engaging positive feedforward.

Employees respond better to constructive and positive feedback rather than negative feedback which can make them feel unappreciated and under-supported.

Constructive feedback is the type of feedback aimed at achieving a positive outcome by providing someone with comments, advice, or suggestions that are useful for their work or their future.

The outcome can be faster processes, improving behaviors, identifying weaknesses, or providing new perspectives.

The feedback can be given in different forms; both praise and criticism can play a role in constructive feedback.

Criticism can also be delivered constructively – constructive criticism . Check out our article to learn more about it.

Good constructive feedback should focus on the work rather than being a personal negative attack against an individual.

Let’s take a look at how praise and criticism work:

Praise is where you show appreciation to your employees for the work they have done.

If an employee has done exemplary work or gone above and beyond to help someone, a thank you and congratulations can go a long way.

By acknowledging their work and showing your appreciation you can help to reinforce these positive behaviors.

Additionally, you can use praise as part of a larger feedback session. By highlighting the things an employee does well your message carries extra weight.

Your employees feel appreciated and any advice shared as part of the feedback will feel positive.

Criticism is harder to navigate as if it is handled poorly it can lead to an uncomfortable working environment .

When critiquing an employee’s work it is imperative to try and make it not personal.

Criticism plays an important role in helping people avoid negative behaviors and grow from their mistakes.

Proper criticism should be sincere and caring whilst also containing a level of importance.

Do not let your emotions get the better of you as criticism levied while you are angry, disappointed, or frustrated may lose its message.

The outcome of criticism should still be positive and contribute to an employee’s growth.

Career development plan template

This template helps employees and bosses plan together for career growth: set goals, assess skills, and make a plan.

Let’s take a look at some good constructive feedback examples.

Each topic is divided into three sections, one which displays appropriate positive feedback (praise), appropriate negative feedback (criticism) and inappropriate negative feedback.

Appropriate types are designed to encourage a positive outcome in the future.

1. Feedback about communication skills

Appropriate positive example.

“Thank you for keeping me informed of the progress on the project for XYZ. It’s allowed me to keep my superiors up-to-date with our department. Everyone is excited to see the project enter the final phase. I’m impressed by your dedication to the team and I look forward to seeing more from you!”

Appropriate negative example

“You haven’t been keeping me well-informed about your project. I don’t know what’s going on and I’d like to see more communication from you. Can we arrange to have a 10-minute call every Friday with progress updates please?”

Inappropriate negative example

“Did no one teach you how to communicate? The team needs to know what’s going on. This is completely unprofessional.”

2. Feedback about work ethic

“I am so impressed with the effort you gave this project. Your commitment to the client and our department is admirable. We were able to sign off on the project ahead of schedule all thanks to you!”

“Thank you for all the hard work you put into this project. Unfortunately, the deadline was missed but I can see the solid effort you gave us. In the future please come to me earlier if you feel a deadline is going to be missed, we can pull in support to ensure this doesn’t happen again.”

“You missed this deadline which has affected our relationship with the client. This reflects poorly on you and the company.”

3. Feedback about leadership

“Seeing you step up and take control of a team has demonstrated your brilliant talent and people skills. Keep it up and you’ll be making a name for yourself here.”

“I’ve noticed that you’re not forthcoming when there are opportunities to lead a project. I appreciate all the work you do and I’d love to see you take on a challenge please let me know if there is anything I can to get you there.”

“If you’re not going to take these opportunities then why are you even here?”

4. Feedback about flexibility

“Thank you for staying late recently, the work has really piled up and we’re really lucky to have a dedicated person like you on the team to help us reach the deadlines.”

“The deadlines are fast approaching and I’ve noticed you haven’t picked up any extra hours to help out. I would like to see a little more flexibility from you to help us get the project done before the deadlines.”

“You can’t just leave when there is work to be done. Your colleagues are staying behind to help so why aren’t you? You need to be doing your bit.”

5. Feedback about creativity

“You are very innovative with the way you work. The creative solutions you have shared with the team are invaluable and will save the company time and money in the future.”

“I’ve noticed that you’ve been getting stuck on tasks recently. Don’t be afraid to get creative with ideas to help you get the world done.”

“There are rules set out for a reason and you should be following them. You aren’t paid to think, you’re paid to work so keep your ideas to yourself.”

6. Feedback about attention to details

“You have such a keen eye for detail. Thanks to your ability to spot errors and resolve them quickly I have been able to free up another member of the team for a new project.”

“I’ve noticed a pattern starting to emerge with your work recently, small errors are slipping through. I know that sometimes this happens so I just wanted to bring it to your attention so we can avoid them in the future. I’ve created a short checklist to go over before you submit your next few projects.”

“You need to start paying more attention to your work. You can’t keep submitting work that falls below the standards we expect of you.”

7. Feedback about punctuality

“I just wanted to take a moment to thank you for always being here on time. It’s really beneficial to have you hear for these early meetings.”

“I’ve noticed that you’ve been coming into the office late this week. The morning meetings are vitally important and I’d like to see you at more of them. Please let me know if there is anything I can do to support you and get you through the doors a little earlier.”

“Your tardiness is unacceptable and it makes everyone look bad. Show up on time or we will have to take disciplinary action.”

8. Feedback about productivity

“I just wanted to let you know that your hard work has not gone unnoticed. Thank you for the extra effort you have been putting in recently. You are a testament to the department and this company.”

“It’s been noted that your productivity has suffered in recent weeks. I’d like to see you back up to your previous levels and if there is anything the company can do to help please let me know. We’ll schedule a meeting a week from now to check on your progress.”

“You’re not working hard enough anymore. You need to get back up to speed with everyone else as soon as possible.”

9. Feedback about attitude and rudeness

“Thank you for being such a positive spirit around the office. Your ability to lighten the mood and keep things upbeat even against tight deadlines has such a positive effect on your colleagues. The environment would not be the same without you!”