- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Don't Miss a Post! Subscribe

- Guest Posts

- Educational AI

- Edtech Tools

- Edtech Apps

- Teacher Resources

- Special Education

- Edtech for Kids

- Buying Guides for Teachers

Educators Technology

Innovative EdTech for teachers, educators, parents, and students

80 Learning Reflection Questions for Students

By Med Kharbach, PhD | Last Update: May 6, 2024

Reflection questions are an important way to boost students’ engagement and enhance their learning. By encouraging learners to ponder their experiences, understandings, and feelings about what they’ve learned, we open a gateway to deeper comprehension and personal growth.

This process not only solidifies their grasp on the material but also cultivates critical thinking and self-awareness. Throughout this post, I’ll share the insights and techniques I’ve gained from my years in the classroom, with a focus on the power and purpose of reflection questions in fostering deep learning.

What are Reflection Questions?

Before we define reflective questions, let’s first discuss what reflection is. Citing ASCD, Purdue defines reflection as “a process where students describe their learning, how it changed, and how it might relate to future learning experiences”.

Based on this definition, reflection questions, are tools that prompt introspection and critical thinking. They empower students to questions their acquired knowledge and transform their experiences into meaningful understandings and personal growth. But this isn’t just based on my personal experience – research supports the idea that reflection plays a critical role in the learning process.

Studies show that when students pause to reflect on their learning journey—assessing their understanding, evaluating their performance, setting future goals, and analyzing their group work—it leads to increased self-awareness , responsibility for learning, and improved academic performance.

Over the years, I’ve integrated these reflection techniques into my teaching practice and have witnessed first-hand the profound impact they can have. It’s always a joy to see my students evolve from passive recipients of information to active, engaged learners who take ownership of their educational journey.

In this post, we’ll dive deeper into how teachers can incorporate reflection questions into their teaching strategies , the best times to use these questions, and a list of reflection question examples for different scenarios. So whether you’re a fellow teacher looking for inspiration or an interested parent wanting to support your child’s learning, read on.

Importance of Reflection Questions in Learning

Reflection is an integral part of the learning process, and its importance for students cannot be overstated. It acts as a bridge between experiences and learning, transforming information into meaningful knowledge.

However, as Bailey and Rehman reported in the Harvard Business Review, to reap the benefits of reflection, one needs to make the act of reflecting a habit. You need to incorporate it in your daily practice and use both forms reflection in action (while being engaged in doing the action) and reflection on action (after the action has taken place).

The following are some of the benefits of integrating reflection questions in learning:

1. Boosts Self-Awareness

Reflection encourages students to think deeply about their own learning process. It prompts them to ask themselves questions about what they’ve learned, how they’ve learned it, and what it means to them.

This practice cultivates self-awareness, making students more conscious of their learning strengths, weaknesses, styles, and preferences. As students better understand their unique learning journey, they become more equipped to tailor their learning strategies in ways that work best for them.

2. Fosters Responsibility for Learning

When students reflect on their learning, they are actively involved in the process of their own education. This involvement fosters a sense of ownership and r esponsibility . It transforms students from passive recipients of knowledge to active participants in their learning journey. They start to recognize that the onus of learning lies with them, making them more committed and proactive learners.

3. Promotes Personal Growth

Reflection is not only about academic growth; it’s also about personal and professional development . When students reflect, they evaluate their actions, decisions, and behaviors, along with their learning.

This helps them identify not only what they need to learn but also what they need to do differently. They gain insights into their personal growth, such as improving their time management, being more collaborative, or handling stress better. This promotes the development of life skills that are crucial for their future.

4. Enhances Critical Thinking

Reflection also enhances critical thinking skills. When students reflect, they analyze their learning experiences, break them down, compare them, and draw conclusions. This practice of critical analysis helps them embrace a questioning attitude and therefore fosters the development of their critical thinking abilities.

5. Facilitates Continuous Improvement

Reflection is a self-regulatory practice that helps students identify areas of improvement. By reflecting on what worked, what didn’t, and why, students can pinpoint the areas they need to focus on. This paves the way for continuous improvement , helping them to become lifelong learners.

Tips to Incorporate reflection questions in your teaching

As teachers and educators, you can use reflection questions to deepen student understanding and promote active engagement with the learning material. Here are few tips to help you integrate reflection questions in your teaching:

1. Incorporating Reflection Questions into Lessons

- Introduce at the End of a Lesson: One of the most common times to use reflection questions is at the end of a lesson. This helps students to review and consolidate the key concepts they have just learned. For example, you might ask, “What was the most important thing you learned today?” or “What questions do you still have about the topic?”

- Use in Class Discussions: You can also incorporate reflection questions into your classroom discussions to foster a deeper understanding of the topics at hand. These questions can push students to think beyond the surface level and engage with the material in a more meaningful way.

- Incorporate in Assignments: Reflection questions can be included as part of homework assignments or projects. For instance, after a group project, you could ask, “How did your team work together?” or “What role did you play in the group, and how did it contribute to the final outcome?”

2. Choosing the Right Time to Use Reflection Questions

- After Lessons: As mentioned above, reflection questions can be highly effective when used immediately after a lesson. This is when the information is still fresh in students’ minds, and they can easily connect the concepts they’ve learned.

- End of the School Day: At the end of the school day, reflection questions can help students recall what they’ve learned across different subjects. This can help in connecting concepts across disciplines and promote broader understanding.

- After a Project or Unit: When a project, assignment, or unit is completed, reflection questions can help students consider their performance, what they learned, what challenges they faced, and how they overcame those challenges. It’s an opportunity for them to recognize their growth over time and understand how they can improve in the future.

- During Parent-Teacher Conferences: Reflection questions can also be useful during parent-teacher conferences. Teachers can share these reflections with parents to provide them with insights into their child’s learning process, strengths, and areas of improvement.

Keep in mind that the goal of these questions is not to judge or grade students but to promote introspection, self-awareness, and active participation in their own learning journey. The responses to reflection questions should be valued for the thought process they reveal and the learning they represent, not just the final answer.

Reflection Questions for Understanding Concepts

These reflection questions aim to prompt students to think deeply about the content of the lesson, ensuring they truly grasp the material rather than just memorizing facts. Effective reflection requires an environment where students feel comfortable expressing their thoughts, doubts, and feelings, so it’s important to create a supportive and non-judgmental classroom culture.

Below are ten examples of reflection questions that can help students evaluate their understanding of key concepts or lessons:

- What was the most important thing you learned in today’s lesson?

- Can you summarize the main idea or theme of the lesson in your own words?

- Was there anything you found confusing or difficult to understand? If so, what?

- How does this concept relate to what we learned previously? Can you draw connections?

- How would you explain this concept to a friend who missed the lesson?

- What were the key points or steps in today’s lesson that helped you understand the concept?

- If you could ask the teacher one question about today’s lesson, what would it be?

- Can you provide an example of how this concept applies in real life?

- Did today’s lesson change your perspective or understanding about the topic? If so, how?

- What strategies or methods did you find helpful in understanding today’s lesson?

Reflection Questions for Self-Assessment

These questions encourage students to look inward and evaluate their performance, behaviors, and strategies. They provide valuable insights that can guide students in setting goals for improvement and taking responsibility for their learning. The goal of these questions is not to make students feel criticized, but to empower them to become more proactive, effective learners.

Here are ten examples of self-assessment reflection questions:

- What was the most challenging part of the lesson/project for you, and how did you overcome that challenge?

- What are some strengths you utilized in today’s lesson/project?

- Are there any areas you think you could have done better in? What are they?

- Did you meet your learning goals for today’s lesson/project? Why or why not?

- What is something you’re proud of in your work today?

- What learning strategies did you use today, and how effective were they?

- If you were to do this lesson/project again, what would you do differently?

- What steps did you take to stay organized and manage your time effectively during the lesson/project?

- How well did you collaborate with others (if applicable) in today’s lesson/project?

- On a scale of 1-10, how would you rate your effort on this lesson/project, and why?

Reflection Questions for Group Work and Collaboration

These questions prompt students to reflect on their collaborative skills, from communication and decision-making to conflict resolution and leadership. The insights gained can guide students to improve their future collaborative efforts, enhancing not only their learning but also their teamwork skills, which are vital for their future careers.

Here are ten reflection questions designed to help students evaluate their performance and experience within a group setting:

- What role did you play in your group, and how did it contribute to the project’s outcome?

- What were the strengths of your group? How did these strengths contribute to the completion of the project?

- Were there any challenges your group faced? How were they resolved?

- What did you learn from your group members during this project?

- If you could change one thing about the way your group worked together, what would it be and why?

- How did your group make decisions? Was this method effective?

- What was the most valuable contribution you made to the group project?

- What is one thing you would do differently in future group work?

- Did everyone in your group contribute equally? If not, how did this impact the group dynamics and the final product?

- What skills did you use during group work, and how can you further improve these skills for future collaboration?

Reflection Questions for Goal Setting

- Based on your recent performance, what is one learning goal you would like to set for the next lesson/unit/project?

- What specific steps will you take to achieve this goal?

- What resources or support do you think you will need to reach your goal?

- How will you know when you have achieved this goal? What will success look like?

- What is one thing you could improve in the next lesson/unit/project?

- What skills would you like to improve or develop in the next term?

- What learning strategies do you plan to use in future lessons to help you understand the material better?

- How do you plan to improve your collaboration with others (if applicable) in future projects or group tasks?

- How can you better manage your time or stay organized in future lessons/projects?

- How can you apply what you’ve learned in this lesson/unit/project to future lessons or real-world situations?

Reflection Questions for Students After a Project

- What part of this project did you enjoy the most, and why?

- What challenges did you face during this project, and how did you overcome them?

- If you were to do this project again, what would you do differently?

- What skills did you utilize for this project?

- How does this project connect to what you’ve previously learned?

Reflection Questions for Students About Behavior

- How do you feel your behavior affects your learning?

- Can you identify a time when your behavior positively impacted others?

- How can you improve your behavior in the next term?

- What triggers certain behaviors, and how can you manage these triggers?

- How do you plan to exhibit positive behavior in the future?

Reflection Questions for Students After Watching a Video

- What is the main message or idea of the video?

- How does the content of the video relate to what we’re learning?

- What part of the video stood out to you the most, and why?

- What questions do you have after watching the video?

- Can you apply the lessons from the video to real-world scenarios?

Reflection Questions for Students at the End of the Year

- What is the most significant thing you’ve learned this year?

- Which areas have you seen the most growth in?

- What was the most challenging part of the year for you, and how did you overcome it?

- What are your learning goals for the next school year?

- How have you changed as a learner over this school year?

Reflection Questions for Students After a Test

- How well do you feel you prepared for the test?

- What part of the test did you find most challenging and why?

- Based on your performance, what areas do you need to focus on for future tests?

- How did you handle the stress or pressure of the test?

- What will you do differently to prepare for the next test?

Reflection Questions for Students After a Unit

- What was the most important concept you learned in this unit?

- How can you apply the knowledge from this unit to other subjects or real-life situations?

- Were there any concepts in this unit you found confusing or difficult?

- How does this unit connect to the overall course objectives?

- What strategies helped you learn the material in this unit?

Reflection Questions for Students After Reading

- What is the main idea or theme of the text?

- How do the characters or events in the text relate to your own experiences?

- What questions do you have after reading the text?

- How has this reading changed your perspective on the topic?

- What part of the text resonated with you the most, and why?

Reflection Questions for Students After a Semester

- What are three significant things you’ve learned this semester?

- What strategies did you use to stay organized and manage your time effectively?

- How have you grown personally and academically this semester?

- What challenges did you face this semester, and how did you overcome them?

- What are your goals for the next semester?

Final thoughts

Circling back to the heart of this post, reflection questions are undeniably a potent catalyst for meaningful learning. They are more than just queries thrown at the end of a lesson; they are introspective prompts that nudge learners to weave together the tapestry of their educational journey with threads of self-awareness, critical analysis, and personal growth. It’s through these questions that students can reflect on their academic canvas and begin to paint a picture of who they are and who they aspire to be in this ever-evolving world of knowledge.

References and Further Readings

Sources cited in the post:

- Driving Continuous Improvement through Reflective Practice, stireducation.org

- Practice-based and Reflective Learning, https://libguides.reading.ac.uk/

- Don’t underestimate the Power of Self-reflection, https://hbr.org/

- Reflective Practice, https://le.unimelb.edu.au/

- Reflection in Learning, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1210944.pdf

- The purpose of Reflection, https://www.cla.purdue.edu/

- Self-reflection and Academic Performance: Is There A Relationship, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Reflection and Self-awareness, https://academic.oup.com/

Further Readings

A. Books on reflective learning

- Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2007). “ Facilitating Reflective Learning in Higher Education “. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Dewey, J. (1933). “ How We Think “.

- Moon, J. A. (2013). Reflection in Learning and Professional Development .

- Schön, D. A. (1983). “ The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action “. Basic Books.

- Gibbs, G. (1988). “ Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods “. FEU.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). “Promoting Reflection in Learning: A Model”. In Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning . Kogan Page.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). “ Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development “. Prentice-Hall.

- Rolheiser, C., Bower, B., & Stevahn, L. (2000). “ The Portfolio Organizer: Succeeding with Portfolios in Your Classroom “. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

B. Peer-reviewed journal articles

- Rusche, S. N., & Jason, K. (2011). “You Have to Absorb Yourself in It”: Using Inquiry and Reflection to Promote Student Learning and Self-knowledge. Teaching Sociology, 39(4), 338–353. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41308965

- Ciardiello, A. V. (1993). Training Students to Ask Reflective Questions. The Clearing House, 66(5), 312–314. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30188906

- Lee, Y., & Kinzie, M. B. (2012). Teacher question and student response with regard to cognition and language use. Instructional Science, 40(6), 857–874. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43575388

- Gunderson, A. (2017). The Well-Crafted Question: Inspiring Students To Connect, Create And Think Critically. American Music Teacher, 66(5), 14–18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26387562

- Grossman, R. (2009). STRUCTURES FOR FACILITATING STUDENT REFLECTION. College Teaching, 57(1), 15–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25763356

- Holden, R., Lawless, A., & Rae, J. (2016). From reflective learning to reflective practice: assessing transfer. Studies in Higher Education, 43(7), pages 1172-1183. Jacobs, Steven MN, MA Ed, RN. Reflective learning, reflective practice. Nursing 46(5):p 62-64, May 2016. | DOI: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000482278.79660.f2

- Thompson, G, Pilgrim, A., Oliver, K. (2006). Self-assessment and Reflective Learning for First-year University Geography Students: A Simple Guide or Simply Misguided?. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, Pages 403-420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260500290959

- Kember, D., McKay, J., Sinclair, K., & Kam, F. Y. (2008). “A Four-Category Scheme for Coding and Assessing the Level of Reflection in Written Work”. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education.

Join our mailing list

Never miss an EdTech beat! Subscribe now for exclusive insights and resources .

Meet Med Kharbach, PhD

Dr. Med Kharbach is an influential voice in the global educational technology landscape, with an extensive background in educational studies and a decade-long experience as a K-12 teacher. Holding a Ph.D. from Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Canada, he brings a unique perspective to the educational world by integrating his profound academic knowledge with his hands-on teaching experience. Dr. Kharbach's academic pursuits encompass curriculum studies, discourse analysis, language learning/teaching, language and identity, emerging literacies, educational technology, and research methodologies. His work has been presented at numerous national and international conferences and published in various esteemed academic journals.

Join our email list for exclusive EdTech content.

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Check Out Our 32 Fave Amazon Picks! 📦

45 Awesome Must-Use Questions to Encourage Student Reflection and Growth

Reflection questions for before, during, and after a project or lesson.

Teaching our students the importance of reflecting upon their knowledge, work, effort, and learning is super important, but it’s not always that easy.

Reflection questions allow students to think about their thinking.

This kind of questioning allows students to better understand how they are working or learning so they can make changes and adjustments from there. Reflection takes time, and often students think that once their work is complete, they should be finished. Often, the younger the student, the more difficult it can be to get them to reflect on what they’ve done.

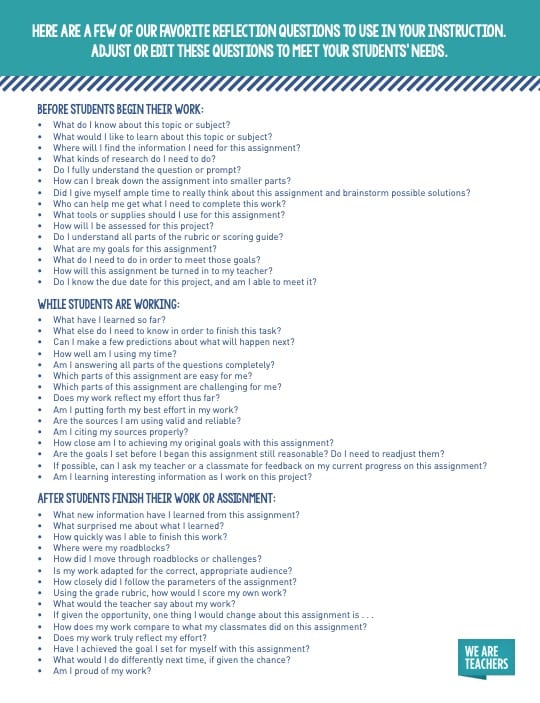

Here are a few of our favorite reflection questions to use in your instruction. Adjust or edit these questions to meet your students’ needs.

Before students begin their work:

- What do I know about this topic or subject?

- What would I like to learn about this topic or subject?

- Where will I find the information I need for this assignment?

- What kinds of research do I need to do?

- Do I fully understand the question or prompt?

- How can I break down the assignment into smaller parts?

- Did I give myself ample time to really think about this assignment and brainstorm possible solutions?

- Who can help me get what I need to complete this work?

- What tools or supplies should I use for this assignment?

- How will I be assessed for this project?

- Do I understand all parts of the rubric or scoring guide?

- What are my goals for this assignment?

- What do I need to do in order to meet those goals?

- How will this assignment be turned in to my teacher?

- Do I know the due date for this project, and am I able to meet it?

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

While students are working:

- What have I learned so far?

- What else do I need to know in order to finish this task?

- Can I make a few predictions about what will happen next?

- How well am I using my time?

- Am I answering all parts of the questions completely?

- Which parts of this assignment are easy for me?

- Which parts of this assignment are challenging for me?

- Does my work reflect my effort thus far?

- Am I putting forth my best effort in my work?

- Are the sources I am using reliable?

- Am I citing my sources properly?

- How close am I to achieving my original goals with this assignment?

- Are the goals I set before I began this assignment still reasonable? Do I need to readjust them?

- If possible, can I ask my teacher or a classmate for feedback on my current progress on this assignment?

- Am I learning interesting information as I work on this project?

After students finish their work or assignment:

- What new information have I learned from this assignment?

- What surprised me about what I learned?

- How quickly was I able to finish this work?

- Where were my roadblocks?

- How did I move through roadblocks or challenges?

- Is my work adapted for the correct, appropriate audience?

- How closely did I follow the parameters of the assignment?

- Using the grade rubric, how would I score my own work?

- What would the teacher say about my work?

- If given the opportunity, one thing I would change about this assignment is …

- How does my work compare to what my classmates did on this assignment?

- Does my work truly reflect my effort?

- Have I achieved the goal I set for myself with this assignment?

- What would I do differently next time, if given the chance?

- Am I proud of my work?

Do you want a short one-page printable of all of these questions to guide your instruction?

Grab the printable version here.

What other questions would you add to this list? Come and share in our WeAreTeachers Chat group on Facebook.

Plus, check out our big list of critical thinking questions and growth mindset posters.

You Might Also Like

17 Homework Memes That Tell It Like It Is

Because the only one that really likes homework is the dog. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Reflective writing is a process of identifying, questioning, and critically evaluating course-based learning opportunities, integrated with your own observations, experiences, impressions, beliefs, assumptions, or biases, and which describes how this process stimulated new or creative understanding about the content of the course.

A reflective paper describes and explains in an introspective, first person narrative, your reactions and feelings about either a specific element of the class [e.g., a required reading; a film shown in class] or more generally how you experienced learning throughout the course. Reflective writing assignments can be in the form of a single paper, essays, portfolios, journals, diaries, or blogs. In some cases, your professor may include a reflective writing assignment as a way to obtain student feedback that helps improve the course, either in the moment or for when the class is taught again.

How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8.

Benefits of Reflective Writing Assignments

As the term implies, a reflective paper involves looking inward at oneself in contemplating and bringing meaning to the relationship between course content and the acquisition of new knowledge . Educational research [Bolton, 2010; Ryan, 2011; Tsingos-Lucas et al., 2017] demonstrates that assigning reflective writing tasks enhances learning because it challenges students to confront their own assumptions, biases, and belief systems around what is being taught in class and, in so doing, stimulate student’s decisions, actions, attitudes, and understanding about themselves as learners and in relation to having mastery over their learning. Reflection assignments are also an opportunity to write in a first person narrative about elements of the course, such as the required readings, separate from the exegetic and analytical prose of academic research papers.

Reflection writing often serves multiple purposes simultaneously. In no particular order, here are some of reasons why professors assign reflection papers:

- Enhances learning from previous knowledge and experience in order to improve future decision-making and reasoning in practice . Reflective writing in the applied social sciences enhances decision-making skills and academic performance in ways that can inform professional practice. The act of reflective writing creates self-awareness and understanding of others. This is particularly important in clinical and service-oriented professional settings.

- Allows students to make sense of classroom content and overall learning experiences in relation to oneself, others, and the conditions that shaped the content and classroom experiences . Reflective writing places you within the course content in ways that can deepen your understanding of the material. Because reflective thinking can help reveal hidden biases, it can help you critically interrogate moments when you do not like or agree with discussions, readings, or other aspects of the course.

- Increases awareness of one’s cognitive abilities and the evidence for these attributes . Reflective writing can break down personal doubts about yourself as a learner and highlight specific abilities that may have been hidden or suppressed due to prior assumptions about the strength of your academic abilities [e.g., reading comprehension; problem-solving skills]. Reflective writing, therefore, can have a positive affective [i.e., emotional] impact on your sense of self-worth.

- Applying theoretical knowledge and frameworks to real experiences . Reflective writing can help build a bridge of relevancy between theoretical knowledge and the real world. In so doing, this form of writing can lead to a better understanding of underlying theories and their analytical properties applied to professional practice.

- Reveals shortcomings that the reader will identify . Evidence suggests that reflective writing can uncover your own shortcomings as a learner, thereby, creating opportunities to anticipate the responses of your professor may have about the quality of your coursework. This can be particularly productive if the reflective paper is written before final submission of an assignment.

- Helps students identify their tacit [a.k.a., implicit] knowledge and possible gaps in that knowledge . Tacit knowledge refers to ways of knowing rooted in lived experience, insight, and intuition rather than formal, codified, categorical, or explicit knowledge. In so doing, reflective writing can stimulate students to question their beliefs about a research problem or an element of the course content beyond positivist modes of understanding and representation.

- Encourages students to actively monitor their learning processes over a period of time . On-going reflective writing in journals or blogs, for example, can help you maintain or adapt learning strategies in other contexts. The regular, purposeful act of reflection can facilitate continuous deep thinking about the course content as it evolves and changes throughout the term. This, in turn, can increase your overall confidence as a learner.

- Relates a student’s personal experience to a wider perspective . Reflection papers can help you see the big picture associated with the content of a course by forcing you to think about the connections between scholarly content and your lived experiences outside of school. It can provide a macro-level understanding of one’s own experiences in relation to the specifics of what is being taught.

- If reflective writing is shared, students can exchange stories about their learning experiences, thereby, creating an opportunity to reevaluate their original assumptions or perspectives . In most cases, reflective writing is only viewed by your professor in order to ensure candid feedback from students. However, occasionally, reflective writing is shared and openly discussed in class. During these discussions, new or different perspectives and alternative approaches to solving problems can be generated that would otherwise be hidden. Sharing student's reflections can also reveal collective patterns of thought and emotions about a particular element of the course.

Bolton, Gillie. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development . London: Sage, 2010; Chang, Bo. "Reflection in Learning." Online Learning 23 (2019), 95-110; Cavilla, Derek. "The Effects of Student Reflection on Academic Performance and Motivation." Sage Open 7 (July-September 2017): 1–13; Culbert, Patrick. “Better Teaching? You Can Write On It “ Liberal Education (February 2022); McCabe, Gavin and Tobias Thejll-Madsen. The Reflection Toolkit . University of Edinburgh; The Purpose of Reflection . Introductory Composition at Purdue University; Practice-based and Reflective Learning . Study Advice Study Guides, University of Reading; Ryan, Mary. "Improving Reflective Writing in Higher Education: A Social Semiotic Perspective." Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2011): 99-111; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8; What Benefits Might Reflective Writing Have for My Students? Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse; Rykkje, Linda. "The Tacit Care Knowledge in Reflective Writing: A Practical Wisdom." International Practice Development Journal 7 (September 2017): Article 5; Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning . Center for Writing, University of Minnesota.

How to Approach Writing a Reflection Paper

Thinking About Reflective Thinking

Educational theorists have developed numerous models of reflective thinking that your professor may use to frame a reflective writing assignment. These models can help you systematically interpret your learning experiences, thereby ensuring that you ask the right questions and have a clear understanding of what should be covered. A model can also represent the overall structure of a reflective paper. Each model establishes a different approach to reflection and will require you to think about your writing differently. If you are unclear how to fit your writing within a particular reflective model, seek clarification from your professor. There are generally two types of reflective writing assignments, each approached in slightly different ways.

1. Reflective Thinking about Course Readings

This type of reflective writing focuses on thoughtfully thinking about the course readings that underpin how most students acquire new knowledge and understanding about the subject of a course. Reflecting on course readings is often assigned in freshmen-level, interdisciplinary courses where the required readings examine topics viewed from multiple perspectives and, as such, provide different ways of analyzing a topic, issue, event, or phenomenon. The purpose of reflective thinking about course readings in the social and behavioral sciences is to elicit your opinions, beliefs, and feelings about the research and its significance. This type of writing can provide an opportunity to break down key assumptions you may have and, in so doing, reveal potential biases in how you interpret the scholarship.

If you are assigned to reflect on course readings, consider the following methods of analysis as prompts that can help you get started :

- Examine carefully the main introductory elements of the reading, including the purpose of the study, the theoretical framework being used to test assumptions, and the research questions being addressed. Think about what ideas stood out to you. Why did they? Were these ideas new to you or familiar in some way based on your own lived experiences or prior knowledge?

- Develop your ideas around the readings by asking yourself, what do I know about this topic? Where does my existing knowledge about this topic come from? What are the observations or experiences in my life that influence my understanding of the topic? Do I agree or disagree with the main arguments, recommended course of actions, or conclusions made by the author(s)? Why do I feel this way and what is the basis of these feelings?

- Make connections between the text and your own beliefs, opinions, or feelings by considering questions like, how do the readings reinforce my existing ideas or assumptions? How the readings challenge these ideas or assumptions? How does this text help me to better understand this topic or research in ways that motivate me to learn more about this area of study?

2. Reflective Thinking about Course Experiences

This type of reflective writing asks you to critically reflect on locating yourself at the conceptual intersection of theory and practice. The purpose of experiential reflection is to evaluate theories or disciplinary-based analytical models based on your introspective assessment of the relationship between hypothetical thinking and practical reality; it offers a way to consider how your own knowledge and skills fit within professional practice. This type of writing also provides an opportunity to evaluate your decisions and actions, as well as how you managed your subsequent successes and failures, within a specific theoretical framework. As a result, abstract concepts can crystallize and become more relevant to you when considered within your own experiences. This can help you formulate plans for self-improvement as you learn.

If you are assigned to reflect on your experiences, consider the following questions as prompts to help you get started :

- Contextualize your reflection in relation to the overarching purpose of the course by asking yourself, what did you hope to learn from this course? What were the learning objectives for the course and how did I fit within each of them? How did these goals relate to the main themes or concepts of the course?

- Analyze how you experienced the course by asking yourself, what did I learn from this experience? What did I learn about myself? About working in this area of research and study? About how the course relates to my place in society? What assumptions about the course were supported or refuted?

- Think introspectively about the ways you experienced learning during the course by asking yourself, did your learning experiences align with the goals or concepts of the course? Why or why do you not feel this way? What was successful and why do you believe this? What would you do differently and why is this important? How will you prepare for a future experience in this area of study?

NOTE: If you are assigned to write a journal or other type of on-going reflection exercise, a helpful approach is to reflect on your reflections by re-reading what you have already written. In other words, review your previous entries as a way to contextualize your feelings, opinions, or beliefs regarding your overall learning experiences. Over time, this can also help reveal hidden patterns or themes related to how you processed your learning experiences. Consider concluding your reflective journal with a summary of how you felt about your learning experiences at critical junctures throughout the course, then use these to write about how you grew as a student learner and how the act of reflecting helped you gain new understanding about the subject of the course and its content.

ANOTHER NOTE: Regardless of whether you write a reflection paper or a journal, do not focus your writing on the past. The act of reflection is intended to think introspectively about previous learning experiences. However, reflective thinking should document the ways in which you progressed in obtaining new insights and understandings about your growth as a learner that can be carried forward in subsequent coursework or in future professional practice. Your writing should reflect a furtherance of increasing personal autonomy and confidence gained from understanding more about yourself as a learner.

Structure and Writing Style

There are no strict academic rules for writing a reflective paper. Reflective writing may be assigned in any class taught in the social and behavioral sciences and, therefore, requirements for the assignment can vary depending on disciplinary-based models of inquiry and learning. The organization of content can also depend on what your professor wants you to write about or based on the type of reflective model used to frame the writing assignment. Despite these possible variations, below is a basic approach to organizing and writing a good reflective paper, followed by a list of problems to avoid.

Pre-flection

In most cases, it's helpful to begin by thinking about your learning experiences and outline what you want to focus on before you begin to write the paper. This can help you organize your thoughts around what was most important to you and what experiences [good or bad] had the most impact on your learning. As described by the University of Waterloo Writing and Communication Centre, preparing to write a reflective paper involves a process of self-analysis that can help organize your thoughts around significant moments of in-class knowledge discovery.

- Using a thesis statement as a guide, note what experiences or course content stood out to you , then place these within the context of your observations, reactions, feelings, and opinions. This will help you develop a rough outline of key moments during the course that reflect your growth as a learner. To identify these moments, pose these questions to yourself: What happened? What was my reaction? What were my expectations and how were they different from what transpired? What did I learn?

- Critically think about your learning experiences and the course content . This will help you develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding about why these moments were significant or relevant to you. Use the ideas you formulated during the first stage of reflecting to help you think through these moments from both an academic and personal perspective. From an academic perspective, contemplate how the experience enhanced your understanding of a concept, theory, or skill. Ask yourself, did the experience confirm my previous understanding or challenge it in some way. As a result, did this highlight strengths or gaps in your current knowledge? From a personal perspective, think introspectively about why these experiences mattered, if previous expectations or assumptions were confirmed or refuted, and if this surprised, confused, or unnerved you in some way.

- Analyze how these experiences and your reactions to them will shape your future thinking and behavior . Reflection implies looking back, but the most important act of reflective writing is considering how beliefs, assumptions, opinions, and feelings were transformed in ways that better prepare you as a learner in the future. Note how this reflective analysis can lead to actions you will take as a result of your experiences, what you will do differently, and how you will apply what you learned in other courses or in professional practice.

Basic Structure and Writing Style

Reflective Background and Context

The first part of your reflection paper should briefly provide background and context in relation to the content or experiences that stood out to you. Highlight the settings, summarize the key readings, or narrate the experiences in relation to the course objectives. Provide background that sets the stage for your reflection. You do not need to go into great detail, but you should provide enough information for the reader to understand what sources of learning you are writing about [e.g., course readings, field experience, guest lecture, class discussions] and why they were important. This section should end with an explanatory thesis statement that expresses the central ideas of your paper and what you want the readers to know, believe, or understand after they finish reading your paper.

Reflective Interpretation

Drawing from your reflective analysis, this is where you can be personal, critical, and creative in expressing how you felt about the course content and learning experiences and how they influenced or altered your feelings, beliefs, assumptions, or biases about the subject of the course. This section is also where you explore the meaning of these experiences in the context of the course and how you gained an awareness of the connections between these moments and your own prior knowledge.

Guided by your thesis statement, a helpful approach is to interpret your learning throughout the course with a series of specific examples drawn from the course content and your learning experiences. These examples should be arranged in sequential order that illustrate your growth as a learner. Reflecting on each example can be done by: 1) introducing a theme or moment that was meaningful to you, 2) describing your previous position about the learning moment and what you thought about it, 3) explaining how your perspective was challenged and/or changed and why, and 4) introspectively stating your current or new feelings, opinions, or beliefs about that experience in class.

It is important to include specific examples drawn from the course and placed within the context of your assumptions, thoughts, opinions, and feelings. A reflective narrative without specific examples does not provide an effective way for the reader to understand the relationship between the course content and how you grew as a learner.

Reflective Conclusions

The conclusion of your reflective paper should provide a summary of your thoughts, feelings, or opinions regarding what you learned about yourself as a result of taking the course. Here are several ways you can frame your conclusions based on the examples you interpreted and reflected on what they meant to you. Each example would need to be tied to the basic theme [thesis statement] of your reflective background section.

- Your reflective conclusions can be described in relation to any expectations you had before taking the class [e.g., “I expected the readings to not be relevant to my own experiences growing up in a rural community, but the research actually helped me see that the challenges of developing my identity as a child of immigrants was not that unusual...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can explain how what you learned about yourself will change your actions in the future [e.g., “During a discussion in class about the challenges of helping homeless people, I realized that many of these people hate living on the street but lack the ability to see a way out. This made me realize that I wanted to take more classes in psychology...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can describe major insights you experienced a critical junctures during the course and how these moments enhanced how you see yourself as a student learner [e.g., "The guest speaker from the Head Start program made me realize why I wanted to pursue a career in elementary education..."].

- Your reflective conclusions can reconfigure or reframe how you will approach professional practice and your understanding of your future career aspirations [e.g.,, "The course changed my perceptions about seeking a career in business finance because it made me realize I want to be more engaged in customer service..."]

- Your reflective conclusions can explore any learning you derived from the act of reflecting itself [e.g., “Reflecting on the course readings that described how minority students perceive campus activities helped me identify my own biases about the benefits of those activities in acclimating to campus life...”].

NOTE: The length of a reflective paper in the social sciences is usually less than a traditional research paper. However, don’t assume that writing a reflective paper is easier than writing a research paper. A well-conceived critical reflection paper often requires as much time and effort as a research paper because you must purposeful engage in thinking about your learning in ways that you may not be comfortable with or used to. This is particular true while preparing to write because reflective papers are not as structured as a traditional research paper and, therefore, you have to think deliberately about how you want to organize the paper and what elements of the course you want to reflect upon.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not limit yourself to using only text in reflecting on your learning. If you believe it would be helpful, consider using creative modes of thought or expression such as, illustrations, photographs, or material objects that reflects an experience related to the subject of the course that was important to you [e.g., like a ticket stub to a renowned speaker on campus]. Whatever non-textual element you include, be sure to describe the object's relevance to your personal relationship to the course content.

Problems to Avoid

A reflective paper is not a “mind dump” . Reflective papers document your personal and emotional experiences and, therefore, they do not conform to rigid structures, or schema, to organize information. However, the paper should not be a disjointed, stream-of-consciousness narrative. Reflective papers are still academic pieces of writing that require organized thought, that use academic language and tone , and that apply intellectually-driven critical thinking to the course content and your learning experiences and their significance.

A reflective paper is not a research paper . If you are asked to reflect on a course reading, the reflection will obviously include some description of the research. However, the goal of reflective writing is not to present extraneous ideas to the reader or to "educate" them about the course. The goal is to share a story about your relationship with the learning objectives of the course. Therefore, unlike research papers, you are expected to write from a first person point of view which includes an introspective examination of your own opinions, feelings, and personal assumptions.

A reflection paper is not a book review . Descriptions of the course readings using your own words is not a reflective paper. Reflective writing should focus on how you understood the implications of and were challenged by the course in relation to your own lived experiences or personal assumptions, combined with explanations of how you grew as a student learner based on this internal dialogue. Remember that you are the central object of the paper, not the research materials.

A reflective paper is not an all-inclusive meditation. Do not try to cover everything. The scope of your paper should be well-defined and limited to your specific opinions, feelings, and beliefs about what you determine to be the most significant content of the course and in relation to the learning that took place. Reflections should be detailed enough to covey what you think is important, but your thoughts should be expressed concisely and coherently [as is true for any academic writing assignment].

Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Critical Reflection: Journals, Opinions, & Reactions . University Writing Center, Texas A&M University; Connor-Greene, Patricia A. “Making Connections: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Journal Writing in Enhancing Student Learning.” Teaching of Psychology 27 (2000): 44-46; Good vs. Bad Reflection Papers , Franklin University; Dyment, Janet E. and Timothy S. O’Connell. "The Quality of Reflection in Student Journals: A Review of Limiting and Enabling Factors." Innovative Higher Education 35 (2010): 233-244: How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Amelia TaraJane House. Reflection Paper . Cordia Harrington Center for Excellence, University of Arkansas; Ramlal, Alana, and Désirée S. Augustin. “Engaging Students in Reflective Writing: An Action Research Project.” Educational Action Research 28 (2020): 518-533; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; McGuire, Lisa, Kathy Lay, and Jon Peters. “Pedagogy of Reflective Writing in Professional Education.” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (2009): 93-107; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; How Do I Write Reflectively? Academic Skills Toolkit, University of New South Wales Sydney; Reflective Writing . Skills@Library. University of Leeds; Walling, Anne, Johanna Shapiro, and Terry Ast. “What Makes a Good Reflective Paper?” Family Medicine 45 (2013): 7-12; Williams, Kate, Mary Woolliams, and Jane Spiro. Reflective Writing . 2nd edition. London: Red Globe Press, 2020; Yeh, Hui-Chin, Shih-hsien Yang, Jo Shan Fu, and Yen-Chen Shih. “Developing College Students’ Critical Thinking through Reflective Writing.” Higher Education Research and Development (2022): 1-16.

Writing Tip

Focus on Reflecting, Not on Describing

Minimal time and effort should be spent describing the course content you are asked to reflect upon. The purpose of a reflection assignment is to introspectively contemplate your reactions to and feeling about an element of the course. D eflecting the focus away from your own feelings by concentrating on describing the course content can happen particularly if "talking about yourself" [i.e., reflecting] makes you uncomfortable or it is intimidating. However, the intent of reflective writing is to overcome these inhibitions so as to maximize the benefits of introspectively assessing your learning experiences. Keep in mind that, if it is relevant, your feelings of discomfort could be a part of how you critically reflect on any challenges you had during the course [e.g., you realize this discomfort inhibited your willingness to ask questions during class, it fed into your propensity to procrastinate, or it made it difficult participating in groups].

Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Reflection Paper . Cordia Harrington Center for Excellence, University of Arkansas.

Another Writing Tip

Helpful Videos about Reflective Writing

These two short videos succinctly describe how to approach a reflective writing assignment. They are produced by the Academic Skills department at the University of Melbourne and the Skills Team of the University of Hull, respectively.

- << Previous: Writing a Policy Memo

- Next: Writing a Research Proposal >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- Peterborough

How to Write a Reflection Paper

Why reflective writing, experiential reflection, reading reflection.

- A note on mechanics

Reflection offers you the opportunity to consider how your personal experiences and observations shape your thinking and your acceptance of new ideas. Professors often ask students to write reading reflections. They do this to encourage you to explore your own ideas about a text, to express your opinion rather than summarize the opinions of others. Reflective writing can help you to improve your analytical skills because it requires you to express what you think, and more significantly, how and why you think that way. In addition, reflective analysis asks you to acknowledge that your thoughts are shaped by your assumptions and preconceived ideas; in doing so, you can appreciate the ideas of others, notice how their assumptions and preconceived ideas may have shaped their thoughts, and perhaps recognize how your ideas support or oppose what you read.

Types of Reflective Writing

Popular in professional programs, like business, nursing, social work, forensics and education, reflection is an important part of making connections between theory and practice. When you are asked to reflect upon experience in a placement, you do not only describe your experience, but you evaluate it based on ideas from class. You can assess a theory or approach based on your observations and practice and evaluate your own knowledge and skills within your professional field. This opportunity to take the time to think about your choices, your actions, your successes and your failures is best done within a specific framework, like course themes or work placement objectives. Abstract concepts can become concrete and real to you when considered within your own experiences, and reflection on your experiences allows you to make plans for improvement.

To encourage thoughtful and balanced assessment of readings, many interdisciplinary courses may ask you to submit a reading reflection. Often instructors will indicate to students what they expect of a reflection, but the general purpose is to elicit your informed opinions about ideas presented in the text and to consider how they affect your interpretation. Reading reflections offer an opportunity to recognize – and perhaps break down – your assumptions which may be challenged by the text(s).

Approaches to Reflective Inquiry

You may wonder how your professors assess your reflective writing. What are they looking for? How can my experiences or ideas be right or wrong? Your instructors expect you to critically engage with concepts from your course by making connections between your observations, experiences, and opinions. They expect you to explain and analyse these concepts from your own point of view, eliciting original ideas and encouraging active interest in the course material.

It can be difficult to know where to begin when writing a critical reflection. First, know that – like any other academic piece of writing – a reflection requires a narrow focus and strong analysis. The best approach for identifying a focus and for reflective analysis is interrogation. The following offers suggestions for your line of inquiry when developing a reflective response.

It is best to discuss your experiences in a work placement or practicum within the context of personal or organizational goals; doing so provides important insights and perspective for your own growth in the profession. For reflective writing, it is important to balance reporting or descriptive writing with critical reflection and analysis.

Consider these questions:

- Contextualize your reflection: What are your learning goals? What are the objectives of the organization? How do these goals fit with the themes or concepts from the course?

- Provide important information: What is the name of the host organization? What is their mission? Who do they serve? What was your role? What did you do?

- Analytical Reflection: What did you learn from this experience? About yourself? About working in the field? About society?

- Lessons from reflection: Did your experience fit with the goals or concepts of the course or organization? Why or why not? What are your lessons for the future? What was successful? Why? What would you do differently? Why? How will you prepare for a future experience in the field?

Consider the purpose of reflection: to demonstrate your learning in the course. It is important to actively and directly connect concepts from class to your personal or experiential reflection. The following example shows how a student’s observations from a classroom can be analysed using a theoretical concept and how the experience can help a student to evaluate this concept.

For Example My observations from the classroom demonstrate that the hierarchical structure of Bloom’s Taxonomy is problematic, a concept also explored by Paul (1993). The students often combined activities like application and synthesis or analysis and evaluation to build their knowledge and comprehension of unfamiliar concepts. This challenges my understanding of traditional teaching methods where knowledge is the basis for inquiry. Perhaps higher-order learning strategies like inquiry and evaluation can also be the basis for knowledge and comprehension, which are classified as lower-order skills in Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Critical reflection requires thoughtful and persistent inquiry. Although basic questions like “what is the thesis?” and “what is the evidence?” are important to demonstrate your understanding, you need to interrogate your own assumptions and knowledge to deepen your analysis and focus your assessment of the text.

Assess the text(s):

- What is the main point? How is it developed? Identify the purpose, impact and/or theoretical framework of the text.

- What ideas stood out to me? Why? Were they new or in opposition to existing scholarship?

Develop your ideas:

- What do I know about this topic? Where does my existing knowledge come from? What are the observations or experiences that shape my understanding?

- Do I agree or disagree with this argument? Why?

Make connections:

- How does this text reinforce my existing ideas or assumptions? How does this text challenge my existing ideas or assumptions?

- How does this text help me to better understand this topic or explore this field of study/discipline?

A Note on Mechanics

As with all written assignments or reports, it is important to have a clear focus for your writing. You do not need to discuss every experience or element of your placement. Pick a few that you can explore within the context of your learning. For reflective responses, identify the main arguments or important elements of the text to develop a stronger analysis which integrates relevant ideas from course materials.

Furthermore, your writing must be organized. Introduce your topic and the point you plan to make about your experience and learning. Develop your point through body paragraph(s), and conclude your paper by exploring the meaning you derive from your reflection. You may find the questions listed above can help you to develop an outline before you write your paper.

You should maintain a formal tone, but it is acceptable to write in the first person and to use personal pronouns. Note, however, that it is important that you maintain confidentiality and anonymity of clients, patients or students from work or volunteer placements by using pseudonyms and masking identifying factors.

The value of reflection: Critical reflection is a meaningful exercise which can require as much time and work as traditional essays and reports because it asks students to be purposeful and engaged participants, readers, and thinkers.

- Schools & departments

Structure of academic reflections

Guidance on the structure of academic reflections.

| Term | How it is being used |

|---|---|

| Academic/professional reflection | Any kind of reflection that is expected to be presented for assessment in an academic, professional, or skill development context. Academic reflection will be used primarily, but refer to all three areas. |

| Private reflection | Reflection you do where you are the only intended audience. |

Academic reflections or reflective writing completed for assessment often require a clear structure. Contrary to some people’s belief, reflection is not just a personal diary talking about your day and your feelings.

Both the language and the structure are important for academic reflective writing. For the structure you want to mirror an academic essay closely. You want an introduction, a main body, and a conclusion.

Academic reflection will require you to both describe the context, analyse it, and make conclusions. However, there is not one set of rules for the proportion of your reflection that should be spent describing the context, and what proportion should be spent on analysing and concluding. That being said, as learning tends to happen when analysing and synthesising rather than describing, a good rule of thumb is to describe just enough such that the reader understands your context.

Example structure for academic reflections

Below is an example of how you might structure an academic reflection if you were given no other guidance and what each section might contain. Remember this is only a suggestion and you must consider what is appropriate for the task at hand and for you yourself.

Introduction

Identifies and introduces your experience or learning

- This can be a critical incident

- This can be the reflective prompt you were given

- A particular learning you have gained

When structuring your academic reflections it might make sense to start with what you have learned and then use the main body to evidence that learning, using specific experiences and events. Alternatively, start with the event and build up your argument. This is a question of personal preference – if you aren’t given explicit guidance you can ask the assessor if they have a preference, however both can work.

Highlights why it was important

- This can be suggesting why this event was important for the learning you gained

- This can be why the learning you gained will benefit you or why you appreciate it in your context

You might find that it is not natural to highlight the importance of an event before you have developed your argument for what you gained from it. It can be okay not to explicitly state the importance in the introduction, but leave it to develop throughout your reflection.

Outline key themes that will appear in the reflection (optional – but particularly relevant when answering a reflective prompt or essay)

- This can be an introduction to your argument, introducing the elements that you will explore, or that builds to the learning you have already gained.

This might not make sense if you are reflecting on a particular experience, but is extremely valuable if you are answering a reflective prompt or writing an essay that includes multiple learning points. A type of prompt or question that could particularly benefit from this would be ‘Reflect on how the skills and theory within this course have helped you meet the benchmark statements of your degree’

It can be helpful to explore one theme/learning per paragraph.

Explore experiences

- You should highlight and explore the experience you introduced in the introduction

- If you are building toward answering a reflective prompt, explore each relevant experience.

As reflection is centred around an individual’s personal experience, it is very important to make experiences a main component of reflection. This does not mean that the majority of the reflective piece should be on describing an event – in fact you should only describe enough such that the reader can follow your analysis.

Analyse and synthesise

- You should analyse each of your experiences and from them synthesise new learning

Depending on the requirements of the assessment, you may need to use theoretical literature in your analysis. Theoretical literature is a part of perspective taking which is relevant for reflection, and will happen as a part of your analysis.

Restate or state your learning

- Make a conclusion based on your analysis and synthesis.

- If you have many themes in your reflection, it can be helpful to restate them here.

Plan for the future

- Highlight and discuss how your new-found learnings will influence your future practice

Answer the question or prompt (if applicable)

- If you are answering an essay question or reflective prompt, make sure that your conclusion provides a succinct response using your main body as evidence.

Using a reflective model to structure academic reflections

You might recognise that most reflective models mirror this structure; that is why a lot of the reflective models can be really useful to structure reflective assignments. Models are naturally structured to focus on a single experience – if the assignment requires you to focus on multiple experiences, it can be helpful to simply repeat each step of a model for each experience.

One difference between the structure of reflective writing and the structure of models is that sometimes you may choose to present your learning in the introduction of a piece of writing, whereas models (given that they support working through the reflective process) will have learning appearing at later stages.

However, generally structuring a piece of academic writing around a reflective model will ensure that it involves the correct components, reads coherently and logically, as well as having an appropriate structure.

Reflective journals/diaries/blogs and other pieces of assessed reflection

The example structure above works particularly well for formal assignments such as reflective essays and reports. Reflective journal/blogs and other pieces of assessed reflections tend to be less formal both in language and structure, however you can easily adapt the structure for journals and other reflective assignments if you find that helpful.

That is, if you are asked to produce a reflective journal with multiple entries it will most often (always check with the person who issued the assignment) be a successful journal if each entry mirrors the structure above and the language highlighted in the section on academic language. However, often you can be less concerned with form when producing reflective journals/diaries.

When producing reflective journals, it is often okay to include your original reflection as long as you are comfortable with sharing the content with others, and that the information included is not too personal for an assessor to read.

Developed from:

Ryan, M., 2011. Improving reflective writing in higher education: a social semiotic perspective. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(1), 99-111.

University of Portsmouth, Department for Curriculum and Quality Enhancement (date unavailable). Reflective Writing: a basic introduction [online]. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth.

Queen Margaret University, Effective Learning Service (date unavailable). Reflection. [online]. Edinburgh: Queen Margaret University.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Reflection questions are an important way to boost students’ engagement and enhance their learning. By encouraging learners to ponder their experiences, understandings, and feelings about what they’ve learned, we open a gateway to deeper comprehension and personal growth.

45 Awesome Must-Use Questions to Encourage Student Reflection and Growth. Reflection questions for before, during, and after a project or lesson. Cute pupil writing at desk in classroom at the elementary school. Student girl doing test in primary school.

How to Write a Reflection Paper. Use these 5 tips to write a thoughtful and insightful reflection paper. 1. Answer key questions. To write a reflection paper, you need to be able to observe your own thoughts and reactions to the material you’ve been given. A good way to start is by answering a series of key questions.

Reflective writing is a process of identifying, questioning, and critically evaluating course-based learning opportunities, integrated with your own observations, experiences, impressions, beliefs, assumptions, or biases, and which describes how this process stimulated new or creative understanding about the content of the course.

• Read example reflection papers before you start writing • Create an outline to help you organize your thoughts • Keep asking yourself reflective questions throughout your writing process!

Using reflective assignments can be a great way of synthesising learning and challenging the status quo. This page outlines some of the things to keep in mind when posing reflective assignments.

Types of reflective writing assignments. Critical reflection is often assessed through a wide variety of tools, such as learning and reflective journals, reports, reflection papers, case studies, or narratives.

Reflective writing can help you to improve your analytical skills because it requires you to express what you think, and more significantly, how and why you think that way.

For the structure you want to mirror an academic essay closely. You want an introduction, a main body, and a conclusion. Academic reflection will require you to both describe the context, analyse it, and make conclusions.

What is a Reflection Assignment? Reflection assignments are an opportunity for you to recall an experience you had and reflect on it in a critical, detailed way. This type of assignment is meant to help you integrate course concepts and theory into your thinking about your practice.