- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Editorial Commentaries

- Perspectives

- Cover Archive

- IDSA Journals

- Clinical Infectious Diseases

- Open Forum Infectious Diseases

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About The Journal of Infectious Diseases

- About the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About the HIV Medicine Association

- IDSA COI Policy

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- For Reviewers

- For Press Offices

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Conclusions.

- < Previous

The Extended Impact of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS Research

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tara A Schwetz, Anthony S Fauci, The Extended Impact of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS Research, The Journal of Infectious Diseases , Volume 219, Issue 1, 1 January 2019, Pages 6–9, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy441

- Permissions Icon Permissions

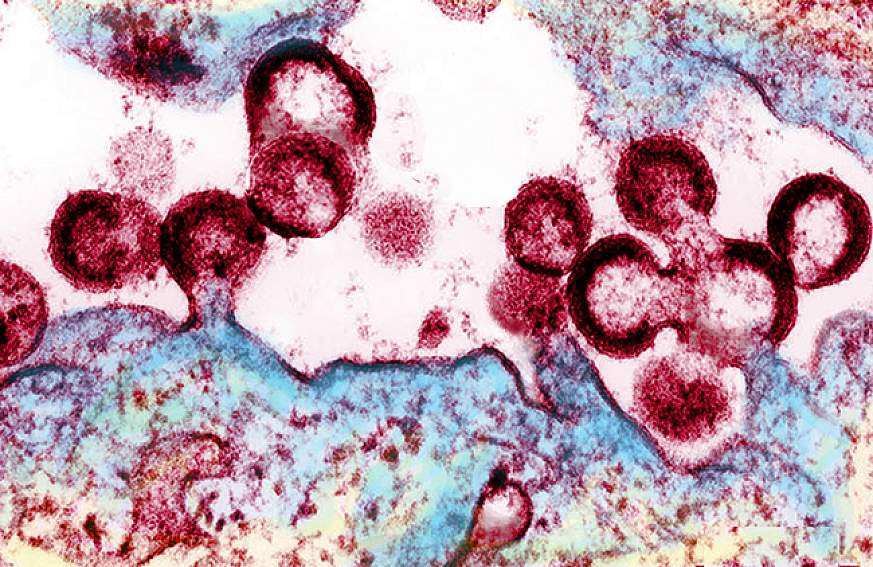

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is one of the most extensively studied viruses in history, and numerous extraordinary scientific advances, including an in-depth understanding of viral biology, pathogenesis, and life-saving antiretroviral therapies, have resulted from investments in HIV/AIDS research. While the substantial investments in HIV/AIDS research are validated solely on these advances, the collateral broader scientific progress resulting from the support of HIV/AIDS research over the past 30 years is extraordinary as well. The positive impact has ranged from innovations in basic immunology and structural biology to treatments for immune-mediated diseases and cancer and has had an enormous effect on the research and public and global health communities well beyond the field of HIV/AIDS. This article highlights a few select examples of the unanticipated and substantial positive spin-offs of HIV/AIDS research on other scientific areas.

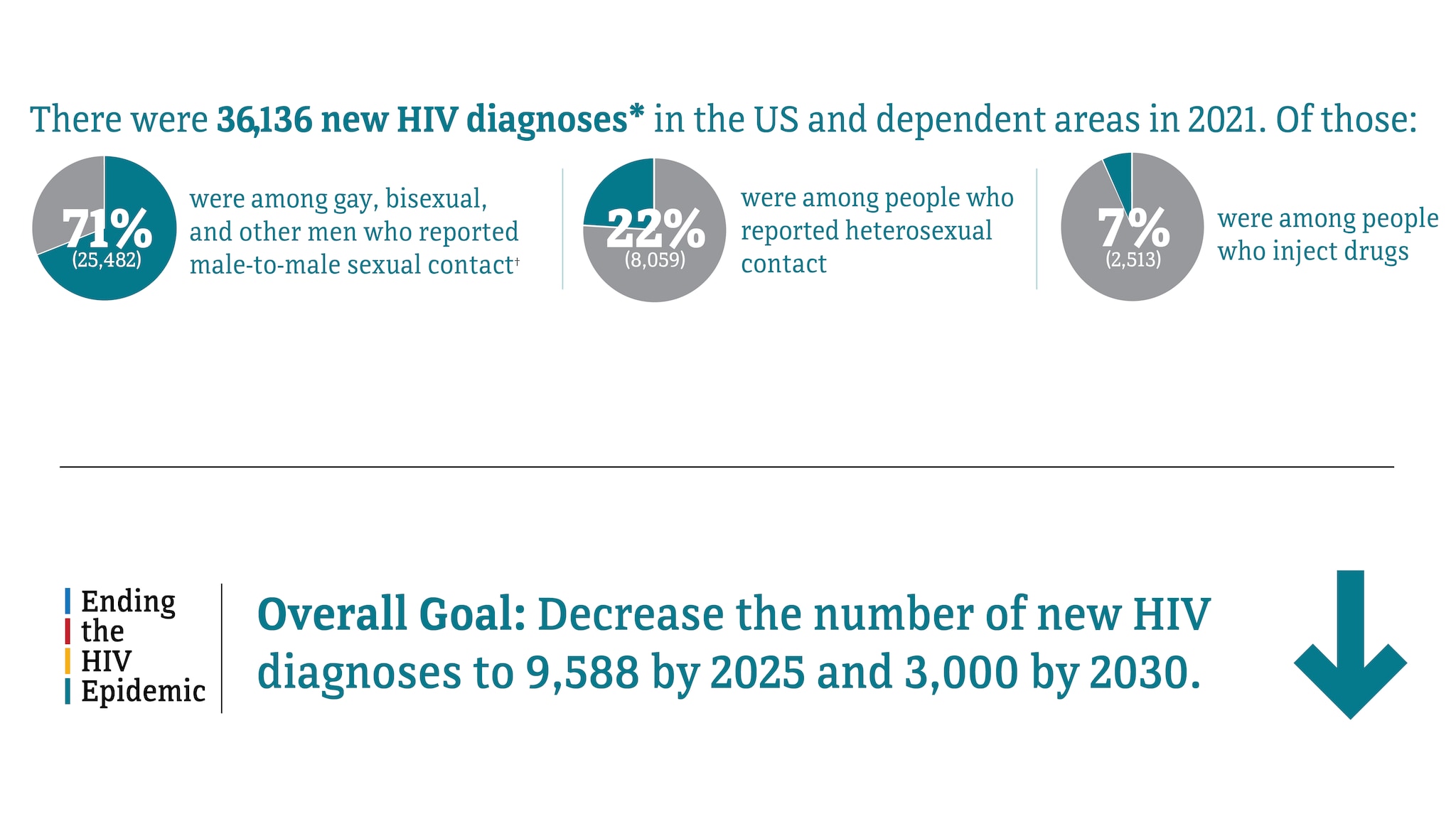

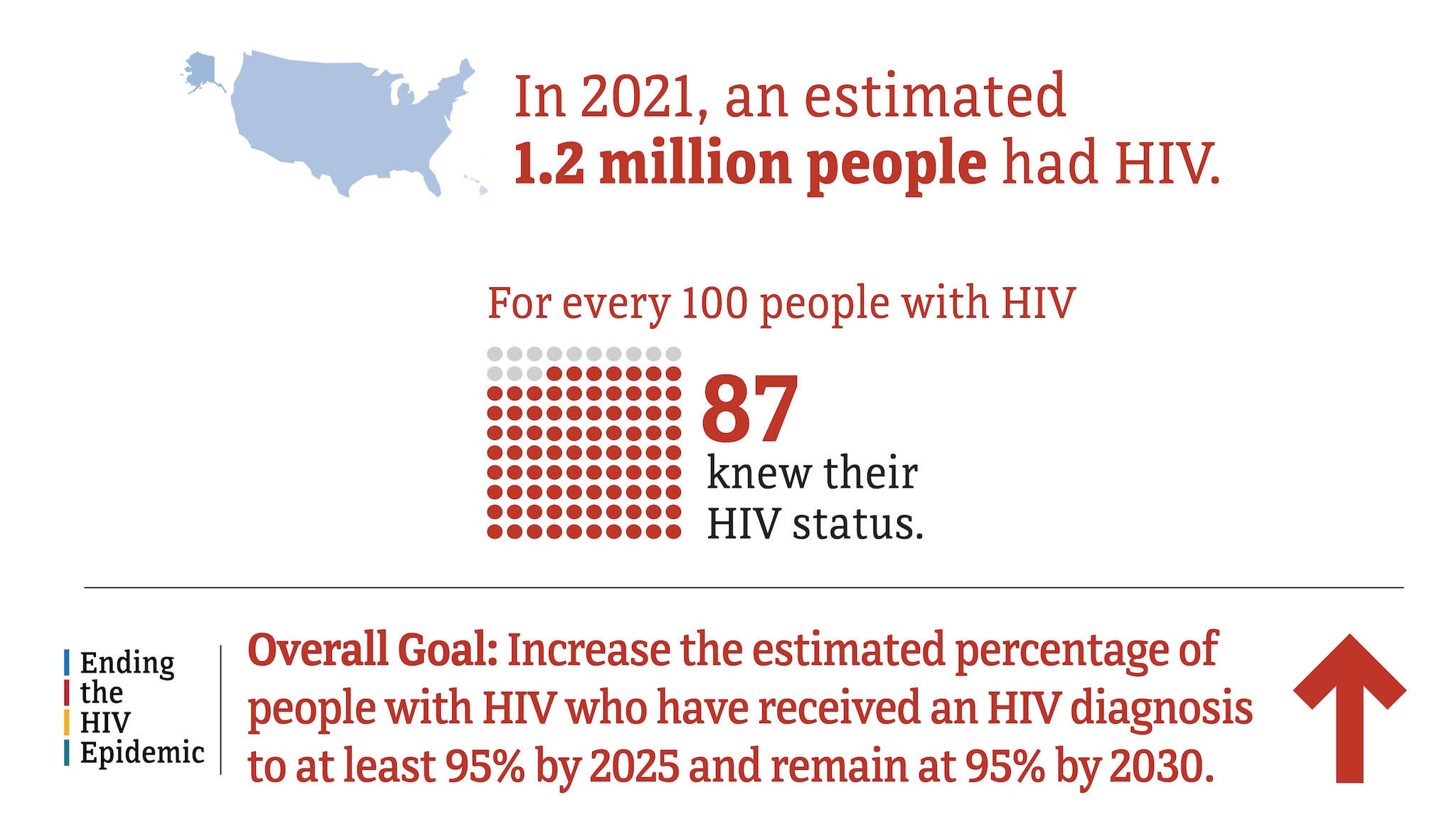

The first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States 37 years ago. Since then, >77 million people have been infected worldwide, resulting in over 35 million deaths. Currently, there are 36.9 million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), 1.8 million new infections, and nearly 1 million AIDS-related deaths annually [ 1 ]. Billions of research dollars have been invested toward understanding, treating, and preventing HIV infection. The largest funder of HIV/AIDS research is the National Institutes of Health (NIH), investing nearly $69 billion in AIDS research from fiscal years 1982–2018. Despite the staggering disease burden, the scientific advances directly resulting from investments in AIDS research have been extraordinary. HIV is one of the most intensively studied viruses in history, leading to an in-depth understanding of viral biology and pathogenesis. However, the most impressive advances in HIV/AIDS research have come in the arena of antiretroviral therapy. Before the development of these life-saving drugs, AIDS was an almost universally fatal disease. Since the demonstration in 1987 that a single drug, zidovudine, better known as azidothymidine or AZT, could partially and temporarily suppress virus replication [ 2 ], the lives of people living with HIV have been transformed by the current availability of >30 antiretroviral drugs that, when administered in combinations of 3 drugs, now in a single daily pill, suppress the virus to undetectable levels. Today, if a person in their 20s is infected and given a combination of antiretroviral drugs that almost invariably will durably suppress virus to below detectable levels, they can anticipate living an additional 50 years, allowing them almost a normal life expectancy [ 3 ]. In addition, a person receiving antiretroviral therapy with an undetectable viral load will not transmit virus to their uninfected sexual partner. This strategy is referred to as “treatment as prevention” [ 4 ]. Also, administration of a single pill containing 2 antiretroviral drugs taken daily by an at-risk uninfected person decreases the chance of acquiring HIV by >95%. Finally, major strides are being made in the quest for a safe and effective HIV vaccine [ 5 ].

The enormous investment in HIV research is clearly justified and validated purely on the basis of advances specifically related to HIV/AIDS. However, the collateral advantages of this investment above and beyond HIV/AIDS have been profound, leading to insights and concrete advances in separate, diverse, and unrelated fields of biomedical research and medicine. In the current Perspective, we discuss a few select examples of the positive spin-offs of HIV/AIDS research on other scientific areas ( Table 1 ).

Positive Spin-offs of Human Immuno deficiency Virus/AIDS Research on Other Areas of Medicine

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

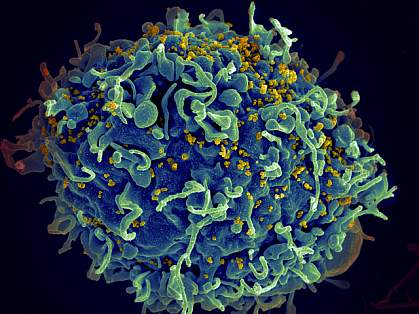

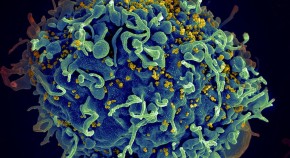

Regulation of the Human Immune System

Congenital immunodeficiencies have been described as “experiments of nature,” whereby a specific defect in a single component of the complex immune system sheds light on the entire system. Such is the case with AIDS, an acquired defect in the immune system whereby HIV specifically and selectively infects and destroys the CD4 + subset of T lymphocytes [ 6 ]. In this respect, HIV infection functions as a natural experiment that elucidates the complexity of the human immune system. The selectivity of this defect and its resulting catastrophic effect on host defense mechanisms, as manifested by the wide range of opportunistic infections and neoplasms, underscore the critical role this cell type plays in the overall regulation of the human immune system. This has provided substantial insights into the pathogenesis of an array of other diseases characterized by aberrancies of immune regulation. Additionally, the in-depth study of immune dysfunction in HIV disease has shed light on the role of the immune system in surveillance against a variety of neoplastic diseases, such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma. As a result of its association with HIV/AIDS, Kaposi sarcoma was discovered to be caused by human herpesvirus 8 [ 7 ].

Targeted Antiviral Drug Development

Targeted antiviral drug development did not begin with HIV infection. However, the enormous investments in biomedical research supported by the NIH and in drug development supported by pharmaceutical companies led to highly effective antiretroviral drugs targeting the enzymes reverse transcriptase, protease, and integrase, among other vulnerable points in the HIV replication cycle, and have transformed the field of targeted drug development, bringing it to an unprecedented level of sophistication. Building on 3 decades of experience, this HIV model has been applied in the successful development of antiviral drugs for other viral diseases, including the highly effective and curative direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C [ 8 ].

Probing the B-Cell Repertoire

The past decade has witnessed extraordinary advances in probing the human B-cell lineage resulting from the availability of highly sophisticated technologies in cellular cloning and genomic sequencing [ 9 ]. AIDS research aimed at developing broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies against HIV and an HIV vaccine that could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies has greatly advanced the field of interrogation of human B-cell lineages, leading to greater insights into the humoral response to other infectious diseases, including Ebola [ 10 ], Zika [ 11 ], and influenza [ 12 ], as well as a range of autoimmune, neoplastic, and other noncommunicable diseases [ 13 ].

Structure-Based Vaccine Design

Although a safe and effective HIV vaccine has not yet been developed, the discipline of structure-based vaccine design using protein X-ray crystallography and cryoelectron microscopy has matured greatly in the context of HIV vaccine research. The design of immunogens based on the precise conformation of epitopes in the viral envelope as they bind to neutralizing antibodies has been perfected within the arena of HIV vaccine immunogen design. This has had immediate positive spinoffs in the design of vaccines for other viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus, in which the prefusion glycoprotein was identified as the important immunogen for a vaccine using structure-based approaches [ 14 ].

Advances in HIV/AIDS-Related Technologies

Insights into the basic immunology of HIV drove the development and optimization of several broadly applicable technologies. Using inactivated HIV as a means of altering T lymphocytes to modulate the immune response, safe lentiviral gene therapy vectors are now US Food and Drug Administration–approved to treat certain cancers (eg, acute lymphoblastic leukemia) [ 15 ]. Additionally, it was discovered early in the epidemic that HIV is associated with the loss of CD4 + T lymphocytes [ 16 ]. While much of the initial research on CD4 + T lymphocytes was possible due to existing flow cytometry technologies, probing the complexities of immune dysregulation in HIV infection spurred the development of multicolor cytofluorometric technologies that have proven extremely useful for studying a variety of other diseases characterized by immune dysfunction [ 17 ]. The reality of utilizing these technologies in resource-poor areas accelerated the advancement of new simplified, automated, affordable, and portable point-of-care devices with broader implications for clinical medicine [ 18 ].

Role of Immune Activation in Disease Pathogenesis

Studying the pathogenesis of HIV disease has clearly demonstrated that aberrant immune activation stimulated by virus replication is the driving force of HIV replication [ 19 ]. In essence, the somewhat paradoxical situation exists whereby the very immune activation triggered by the virus in an attempt to control virus replication creates the microenvironment where the virus efficiently replicates. Even when the virus is effectively suppressed by antiretroviral drugs, a low degree of immune activation persists [ 20 ]. In this regard, the flagrant immune activation associated with uncontrolled virus replication, as well as the subtle immune activation associated with control of virus replication, are important pathogenic triggers of the increased cardiovascular and other organ system diseases associated with HIV infection. This direct association of even subtle levels of immune activation seen in HIV infection with a variety of systemic diseases has led to considerable insight into the role of immune activation and inflammation in human disease [ 21 ]. For example, recognition of the increased incidence of heart disease in the HIV population that is associated with chronic inflammation has stimulated interdisciplinary advances in understanding and treating coronary heart disease apart from HIV infection [ 22 ].

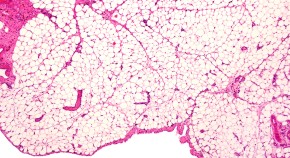

Comorbidities in HIV Disease

Antiretroviral therapy, which has transformed HIV treatment, is shifting the incidence of certain diseases in people living with HIV. Even when well-controlled by antiretrovirals, HIV disease is associated with an increased incidence of diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, kidney and liver disease, the premature appearance of pathophysiologic processes associated with aging, and several cancers [ 21–24 ]. This is especially true for non-AIDS-defining cancers, whose incidence rates are increasing while AIDS-defining cancer rates are decreasing [ 24 ]. In lower-income countries, tuberculosis is a common coinfection with HIV, and HIV coinfection was shown to be a key risk factor for progression of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection to active disease [ 25 ]. There are a variety of ongoing studies [ 21 ] investigating the pathogenic bases of these conditions to shed greater insight into their causes and potential interventions that might impact these diseases apart from HIV infection and immunodeficiency.

The collateral advantages resulting from the substantial resources devoted to HIV/AIDS research over the past 30 years are extraordinary. From innovations in basic immunology and structural biology to treatments for immune-mediated diseases and cancer, the conceptual and technological advances resulting from HIV/AIDS research have had an enormous impact on the research and public and global health communities over and above the field of HIV/AIDS. The HIV/AIDS research model has proven that cross-fertilization of ideas, innovation, and research progress can lead to unforeseen and substantial advantages for a variety of other diseases.

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Carl Dieffenbach, Daniel Rotrosen, Charles Hackett, and Robert Eisinger for their helpful input in preparation of the manuscript.

Potential conflicts of interest. Both authors: No reported conflicts of interest. Both authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Joint United Nations Progamme on HIV/AIDS . Fact sheet: latest statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic . http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet . Accessed 23 July 2018.

Fischl MA , Richman DD , Grieco MH , et al. The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial . N Engl J Med 1987 ; 317 : 185 – 91 .

Google Scholar

Samji H , Cescon A , Hogg RS , et al. North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) of IeDEA . Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada . PLoS One 2013 ; 8 : e81355 .

Lundgren JD , Babiker AG , Gordin F , et al. INSIGHT START Study Group . Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection . N Engl J Med 2015 ; 373 : 795 – 807 .

Trovato M , D’Apice L , Prisco A , De Berardinis P . HIV vaccination: a roadmap among advancements and concerns . Int J Mol Sci 2018 ; 19 . doi: 10.3390/ijms19041241 .

Dalgleish AG , Beverley PC , Clapham PR , Crawford DH , Greaves MF , Weiss RA . The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus . Nature 1984 ; 312 : 763 – 7 .

Schulz TF , Boshoff CH , Weiss RA . HIV infection and neoplasia . Lancet 1996 ; 348 : 587 – 91 .

Wyles DL . Antiviral resistance and the future landscape of hepatitis C virus infection therapy . J Infect Dis 2013 ; 207 ( Suppl 1 ): S33 – 9 .

Boyd SD , Crowe JE Jr . Deep sequencing and human antibody repertoire analysis . Curr Opin Immunol 2016 ; 40 : 103 – 9 .

Flyak AI , Kuzmina N , Murin CD , et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies from human survivors target a conserved site in the Ebola virus glycoprotein HR2-MPER region . Nat Microbiol 2018 ; 3 : 670 – 7 .

Sapparapu G , Fernandez E , Kose N , et al. Neutralizing human antibodies prevent Zika virus replication and fetal disease in mice . Nature 2016 ; 540 : 443 – 7 .

Raymond DD , Bajic G , Ferdman J , et al. Conserved epitope on influenza-virus hemagglutinin head defined by a vaccine-induced antibody . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018 ; 115 : 168 – 73 .

Röhn TA , Bachmann MF . Vaccines against non-communicable diseases . Curr Opin Immunol 2010 ; 22 : 391 – 6 .

Tian D , Battles MB , Moin SM , et al. Structural basis of respiratory syncytial virus subtype-dependent neutralization by an antibody targeting the fusion glycoprotein . Nat Commun 2017 ; 8 : 1877 .

US Food and Drug Administration . FDA approval brings first gene therapy to the United States . Silver Spring, MD : FDA , 2017 .

Google Preview

Gottlieb MS , Schroff R , Schanker HM , et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and mucosal candidiasis in previously healthy homosexual men: evidence of a new acquired cellular immunodeficiency . N Engl J Med 1981 ; 305 : 1425 – 31 .

Chattopadhyay PK , Roederer M . Cytometry: today’s technology and tomorrow’s horizons . Methods 2012 ; 57 : 251 – 8 .

Kestens L , Mandy F . Thirty-five years of CD4 T-cell counting in HIV infection: from flow cytometry in the lab to point-of-care testing in the field . Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2017 ; 92 : 437 – 44 .

Moir S , Fauci AS . B-cell exhaustion in HIV infection: the role of immune activation . Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014 ; 9 : 472 – 7 .

Paiardini M , Müller-Trutwin M . HIV-associated chronic immune activation . Immunol Rev 2013 ; 254 : 78 – 101 .

Lucas S , Nelson AM . HIV and the spectrum of human disease . J Pathol 2015 ; 235 : 229 – 41 .

Boccara F , Lang S , Meuleman C , et al. HIV and coronary heart disease: time for a better understanding . J Am Coll Cardiol 2013 ; 61 : 511 – 23 .

Torres RA , Lewis W . Aging and HIV/AIDS: pathogenetic role of therapeutic side effects . Lab Invest 2014 ; 94 : 120 – 8 .

Thrift AP , Chiao EY . Are non-HIV malignancies increased in the HIV-infected population ? Curr Infect Dis Rep 2018 ; 20 : 22 .

Getahun H , Gunneberg C , Granich R , Nunn P . HIV infection-associated tuberculosis: the epidemiology and the response . Clin Infect Dis 2010 ; 50 ( Suppl 3 ): S201 – 7 .

- acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Email alerts

Related articles in pubmed, citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1537-6613

- Print ISSN 0022-1899

- Copyright © 2024 Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Research & training, advances in hiv/aids research.

For an update on what medical science is doing to fight the global HIV/AIDS pandemic, read a Parade article by NIH Director Francis S. Collins and NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, AIDS in 2010: How We're Living with HIV .

Over the past several decades, researchers have learned a lot about the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the disease it causes, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). But still more research is needed to help the millions of people whose health continues to be threatened by the global HIV/AIDS pandemic.

At the National Institutes of Health, the HIV/AIDS research effort is led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). A vast network of NIAID-supported scientists, located on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, and at research centers around the globe, are exploring new ways to prevent and treat HIV infection, as well as to better understand the virus with the goal of finding a cure. For example, in recent months, NIAID and its partners made progress toward finding a vaccine to prevent HIV infection. Check out other promising areas of NIAID-funded research on HIV/AIDS at http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/hivaids/Pages/Default.aspx .

Other NIH institutes, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, also support research to better control and ultimately end the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Some of these researchers have found a simple, cost-effective way to cut HIV transmission from infected mothers to their breastfed infants. Others have developed an index to help measure the role of alcohol consumption in illness and death of people with HIV/AIDS.

Find out more about these discoveries and what they mean for improving the health of people in the United States and all around the globe.

This page last reviewed on August 20, 2015

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Emily Mullin

There’s New Hope for an HIV Vaccine

Since it was first identified in 1983, HIV has infected more than 85 million people and caused some 40 million deaths worldwide.

While medication known as pre-exposure prophylaxis , or PrEP, can significantly reduce the risk of getting HIV, it has to be taken every day to be effective. A vaccine to provide lasting protection has eluded researchers for decades. Now, there may finally be a viable strategy for making one.

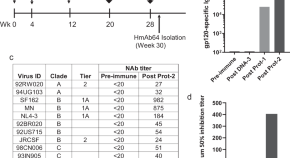

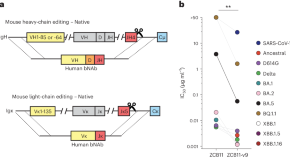

An experimental vaccine developed at Duke University triggered an elusive type of broadly neutralizing antibody in a small group of people enrolled in a 2019 clinical trial. The findings were published today in the scientific journal Cell .

“This is one of the most pivotal studies in the HIV vaccine field to date,” says Glenda Gray, an HIV expert and the president and CEO of the South African Medical Research Council, who was not involved in the study.

A few years ago, a team from Scripps Research and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) showed that it was possible to stimulate the precursor cells needed to make these rare antibodies in people. The Duke study goes a step further to generate these antibodies, albeit at low levels.

“This is a scientific feat and gives the field great hope that one can construct an HIV vaccine regimen that directs the immune response along a path that is required for protection,” Gray says.

Vaccines work by training the immune system to recognize a virus or other pathogen. They introduce something that looks like the virus—a piece of it, for example, or a weakened version of it—and by doing so, spur the body’s B cells into producing protective antibodies against it. Those antibodies stick around so that when a person later encounters the real virus, the immune system remembers and is poised to attack.

While researchers were able to produce Covid-19 vaccines in a matter of months, creating a vaccine against HIV has proven much more challenging. The problem is the unique nature of the virus. HIV mutates rapidly, meaning it can quickly outmaneuver immune defenses. It also integrates into the human genome within a few days of exposure, hiding out from the immune system.

“Parts of the virus look like our own cells, and we don’t like to make antibodies against our own selves,” says Barton Haynes, director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute and one of the authors on the paper.

The particular antibodies that researchers are interested in are known as broadly neutralizing antibodies, which can recognize and block different versions of the virus. Because of HIV’s shape-shifting nature, there are two main types of HIV and each has several strains. An effective vaccine will need to target many of them.

Some HIV-infected individuals generate broadly neutralizing antibodies, although it often takes years of living with HIV to do so, Haynes says. Even then, people don’t make enough of them to fight off the virus. These special antibodies are made by unusual B cells that are loaded with mutations they’ve acquired over time in reaction to the virus changing inside the body. “These are weird antibodies,” Haynes says. “The body doesn’t make them easily.”

By Carlton Reid

By Emily Mullin

By Steven Levy

By Andy Greenberg

Haynes and his colleagues aimed to speed up that process in healthy, HIV-negative people. Their vaccine uses synthetic molecules that mimic a part of HIV’s outer coat, or envelope, called the membrane proximal external region. This area remains stable even as the virus mutates. Antibodies against this region can block many circulating strains of HIV.

The trial enrolled 20 healthy participants who were HIV-negative. Of those, 15 people received two of four planned doses of the investigational vaccine, and five received three doses. The trial was halted when one participant experienced an allergic reaction that was not life-threatening. The team found that the reaction was likely due to an additive in the vaccine, which they plan to remove in future testing.

Still, they found that two doses of the vaccine were enough to induce low levels of broadly neutralizing antibodies within a few weeks. Notably, B cells seemed to remain in a state of development to allow them to continue acquiring mutations, so they could evolve along with the virus. Researchers tested the antibodies on HIV samples in the lab and found that they were able to neutralize between 15 and 35 percent of them.

Jeffrey Laurence, a scientific consultant at the Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) and a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, says the findings represent a step forward, but that challenges remain. “It outlines a path for vaccine development, but there’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” he says.

For one, he says, a vaccine would need to generate antibody levels that are significantly higher and able to neutralize with greater efficacy. He also says a one-dose vaccine would be ideal. “If you’re ever going to have a vaccine that’s helpful to the world, you’re going to need one dose,” he says.

Targeting more regions of the virus envelope could produce a more robust response. Haynes says the next step is designing a vaccine with at least three components, all aimed at distinct regions of the virus. The goal is to guide the B cells to become much stronger neutralizers, Haynes says. “We’re going to move forward and build on what we have learned.”

You Might Also Like …

In your inbox: Will Knight's Fast Forward explores advances in AI

Indian voters are being bombarded with millions of deepfakes

They bought tablets in prison —and found a broken promise

The one thing that’s holding back the heat pump

It's always sunny: Here are the best sunglasses for every adventure

Max G. Levy

Beth Mole, Ars Technica

Carl Zimmer

Matt Reynolds

- Open access

- Published: 17 September 2020

HIV/AIDS research in Africa and the Middle East: participation and equity in North-South collaborations and relationships

- Gregorio González-Alcaide ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3853-5222 1 na1 ,

- Marouane Menchi-Elanzi 2 na1 ,

- Edy Nacarapa 3 , 4 &

- José-Manuel Ramos-Rincón 2 , 5

Globalization and Health volume 16 , Article number: 83 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

18 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

HIV/AIDS has attracted considerable research attention since the 1980s. In the current context of globalization and the predominance of cooperative work, it is crucial to analyze the participation of the countries and regions where the infection is most prevalent. This study assesses the participation of African countries in publications on the topic, as well as the degree of equity or influence existing in North-South relations.

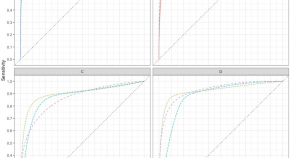

We identified all articles and reviews of HIV/AIDS indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection. We analyzed the scientific production, collaboration, and contributions from African and Middle Eastern countries to scientific activity in the region. The concept of leadership, measured through the participation as the first author of documents in collaboration was used to determine the equity in research produced through international collaboration.

A total of 68,808 documents published from 2010 to 2017 were analyzed. Researchers from North America and Europe participated in 82.14% of the global scientific production on HIV/AIDS, compared to just 21.61% from Africa and the Middle East. Furthermore, the publications that did come out of these regions was concentrated in a small number of countries, led by South Africa (41% of the documents). Other features associated with HIV/AIDS publications from Africa include the importance of international collaboration from the USA, the UK, and other European countries (75–93% of the documents) and the limited participation as first authors that is evident (30 to 36% of the documents). Finally, the publications to which African countries contributed had a notably different disciplinary orientation, with a predominance of research on public health, epidemiology, and drug therapy.

Conclusions

It is essential to foster more balance in research output, avoid the concentration of resources that reproduces the global North-South model on the African continent, and focus the research agenda on local priorities. To accomplish this, the global North should strengthen the transfer of research skills and seek equity in cooperative ties, favoring the empowerment of African countries. These efforts should be concentrated in countries with low scientific activity and high incidence and prevalence of the disease. It is also essential to foster intraregional collaborations between African countries.

HIV infection and its clinical manifestation, AIDS, are considered a pre-eminent challenge for global public health [ 1 ], affecting populations worldwide since the 1980s. Despite the progress made in prevention and treatment programs, the disease is still pandemic, with the African continent being the hardest hit [ 2 ]. An estimated 37.9 million people were living with HIV in 2018, of whom 20.6 million lived in Eastern and Southern Africa, 5 million in Western and Central Africa, and 240,000 in the Middle East and North Africa. The same year saw about 770,000 deaths from this disease and 1.7 million new infections, 61% of which occurred in sub-Saharan Africa. Over half of the new cases in Eastern and Southern Africa were concentrated in Mozambique, South Africa, and Tanzania, while 71% of new infections in Western and Central Africa were in Cameroon, the Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria. In the Middle East and North Africa, two-thirds of new cases were registered in Egypt, Iran and Sudan [ 3 ]. In response to this challenge, researchers worldwide have worked to produce evidence on HIV/AIDS across a wide range of biomedical disciplines, including epidemiology, virology, immunology, and pharmacology, as well as in non-biomedical fields such as social sciences and the humanities. This body of work has situated HIV/AIDS among the most studied infectious diseases today [ 4 ].

Bibliometrics is a method that enables the quantitative and qualitative assessment of scientific research in any area of knowledge, at an individual, institutional, or national level [ 5 ]. In that sense, ample literature has been published on bibliometric analyses of HIV/AIDS research since the 1980s [ 6 , 7 ], including some papers that focus specifically on the regions most affected by the virus and the infection, like Central Africa [ 8 ]; sub-Saharan Africa [ 9 ]; or on countries like Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, or Lesotho [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However, many of these papers were published more than a decade ago and investigated the scientific production in the geographical areas analyzed. In the current context of globalization and predominance of cooperative work, Africans are under-represented in terms of authorship in collaborative research publications. This situation has led some investigators to call for studies that quantify authorship equity [ 13 ] and explore North-South relationships in research collaboration [ 8 ].

The overarching objective of the present study is to provide an up-to-date description of participation from Africa and the Middle East in the literature on HIV/AIDS published in high-visibility journals, and of the role played by researchers from African countries in publications produced in international collaboration. Our specific research questions were: (1) What was the contribution from Africa and the Middle East, both overall and by country, to the global scientific research output on HIV/AIDS? (2) Is North-South participation balanced international collaboration papers? and (3) Are there differences in the subject-area orientation between publications produced with or without participation from African and Middle Eastern authors on HIV/AIDS research?

The methodological process was as follows.

Identification of global scientific research production on HIV/AIDS

To identify the scientific literature on HIV/AIDs, we used the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus of the National Library of Medicine, selecting all of the descriptors related to HIV, human immunodeficiency related to HIV infection, and the development of vaccines for preventing or clinically treating the immunodeficiency. The final MeSH (plus their variants and synonyms) were: HIV, HIV Infections, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, and AIDS Vaccines.

Although the MeSH thesaurus is linked to the MEDLINE database, which is freely available through the PubMed platform, we performed a second search of the documents identified in MEDLINE and which were also indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS-CC) databases. Although this database does not cover all of the documents indexed in MEDLINE/PubMed, it does include all of the institutional affiliations (which MEDLINE started listing only in 2014), making it an ideal source for characterizing scientific production by country and the collaboration from Africa and the Middle East in HIV/AIDS publications during the study period.

The collection of journals in the WoS-CC, moreover, represents the information sources with the highest visibility at an international level. Thus, using that source to calculate our bibliometric study indicators allows a vision of the development of the most relevant and impactful research worldwide.

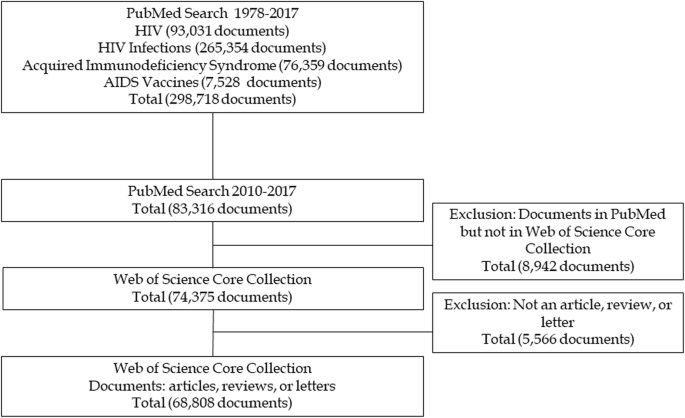

Definition of the document sample analyzed

Our literature search yielded 93,031 documents on HIV, 256,354 on HIV Infections, 76,359 on Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, and 7528 on AIDS Vaccines. After removing duplicate descriptors, there were 298,718 unique documents. We then restricted the results to those published from 2010 to 2017 ( n = 83,316) in order to focus the analysis on the most recent research. We ruled out the inclusion of documents from 2018 to avoid delays related to indexation, as at least a year is needed to ensure updated information related to the assignment of MeSH terms. We subsequently identified the documents that were also included in the WoS-CC databases by searching for all of the documents from the initial sample using their PMIDs (the PubMed identifier used as a reference in MEDLINE and included as a bibliographic field in WoS-CC). In total, 89.29% ( n = 74,375) of the MEDLINE documents were also in the WoS-CC. This set of papers was further restricted to three document types: articles, reviews, and letters ( n = 68,808), chosen because they are the most prominent papers for transmitting the results of original research (articles); situating and evaluating the development of research in a highly relevant way for other researchers (reviews); and contributing critical viewpoints, comments, relevant information, and perspectives on published studies (letters). The searches took place in November 2018. Figure 1 presents a flow chart showing the selection process for the sample of documents analyzed in the study.

Flow chart for the selection of included documents

Download of bibliographic information and review of the standardization of data

Following the bibliographic search and document selection, we downloaded the bibliographic information from the selected records ( n = 68,808), generating a relational database in Microsoft Access in order to enumerate and individualize the multiple entries contained in certain bibliographic fields. This is the case of institutional affiliations, as a single field collates the data for all co-authors’ institutions and countries. Likewise, the subject area field for the journal of publication may also have several assigned topics, and various MeSH and other text words are assigned to different documents to describe their content.

We also reviewed the standardization and quality of the data. For example, we looked at the years of publication, as the date of some documents’ public dissemination on the journal website differed from the definitive date of publication in the journal (the latter was taken as the reference). Likewise, we consolidated all the information on geographic origins from England, Scotland, Wales, and North Ireland—presented individually in the WoS-CC—under the UK.

Identification of participation from Africa and the Middle East in HIV/AIDS publications

To analyze the participation from Africa and the Middle East in HIV/AIDS publications, we took as a reference the UNAIDS (2018) definitions of geographical regions, assigning each country to its respective region as defined in that source. The regions were: North America, Western and Central Europe, Asia and Pacific, Eastern and Southern Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, West and Central Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Indicators obtained and analyses performed

The indicators and analyses applied in our study are structured in three blocks.

Analysis of the scientific production, research collaboration and leadership, by geographical region

As an introductory step to understanding global HIV/AIDS research, we quantified absolute scientific production by UNAIDS regions, calculating the number of documents authored by researchers from these areas. Moreover, we assessed inter-regional and international collaboration along with research leadership. The concepts used in the present study are defined as follows:

- International collaboration: joint participation in the authorship of a document by researchers from two or more countries.

- Inter-regional collaboration: joint participation in the authorship of a document by researchers from countries in two or more regions.

- Leadership: the degree of participation as the first author of documents in collaboration (number or % with respect to the total documents produced in collaboration).

Geographical affiliations were based, therefore, on authors’ institutional affiliations. The section on limitations includes an in-depth discussion on the shortcomings of this procedure, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

Analysis of research production, collaboration and leadership from countries in Africa and the Middle East

To specifically analyze HIV/AIDS research publications from African and Middle Eastern countries, we determined the number of documents authored by researchers from these countries as well as the proportion of total publications with their participation. With regard to research collaboration and leadership, the absolute and relative values on international collaboration are complemented by a specific analysis of research leadership in the top 10 most productive countries in Africa. Furthermore, a directed collaboration network was generated, representing the main African countries collaborating in global HIV/AIDS research. The nodes represent countries, and the links represent countries’ participation in the first positions of authorship. This visual representation clarifies the position that different countries occupy in the network and the collaborative links that they have established.

Subject areas and research fields in global HIV/AIDS research production

We analyzed the research subject areas and fields according to the disciplines that contributed most to scientific production on HIV/AIDS, as identified by means of the subject area classification of scientific journals in the WoS-CC as well as the MeSH descriptors and qualifiers assigned to the documents. To compare research orientations, we present data for global research output, for publications produced solely by researchers from African countries, and publications produced through collaborations between researchers from African countries and others (Africa+global collaboration). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was estimated for these three groupings to determine the affinity between African and global research production.

Finally, a co-occurrence network of MeSH terms was generated to analyze the relationships between them and to identify the specific subject areas or research orientations on HIV/AIDS in Africa and the Middle East.

Pajek and VoSViewer (Version 1.6.8, Center for Science and Technology, Leiden University) software were used to perform all processes (analysis, network generation) and obtain all descriptive indicators.

Scientific production by region and degree of international collaboration

Scientific production on HIV/AIDS is dominated by North America (which participated in 55.60% of all documents analyzed) and by Western and Central Europe (35.79%). Together, these regions participated in 82.13% of global scientific research production on HIV/AIDS that was indexed in the sources consulted. For their part, the three regions of Africa and the Middle East participated in 21.61% of the documents, albeit contributions from Eastern and Southern Africa (17.80%) were much higher than those from Western and Central Africa (3.34%) and Middle East and North Africa (1.18%) (Table 1 ). This limited scientific production contrasts with the high percentages of collaboration observed in these regions; in Eastern and Southern Africa, 82.42% of the papers were published in collaboration with authors from countries in other regions, and in Western and Central Africa, 78.39%. In contrast, 43.22% of the documents from North America were produced in inter-regional collaboration, and 47.99% from Western and Central Europe. Looking only at documents produced with inter-regional collaboration, authors from Africa and the Middle East occupied the first position on just 30 to 36% of the papers, compared to 45% for Western and Central Europe and 54% for North America (Table 1 ).

Scientific production by country and degree of international collaboration

Research production in Africa and the Middle East is concentrated in South Africa, whose researchers participated in 40.94% of the documents from these regions. At some distance are several other countries from Eastern and Southern Africa: Uganda (12.97%), Kenya (10.71%), Malawi (6.19%) and Tanzania (6.03%). Thirteen other countries show values ranging from 1.32 to 4.73%. Nigeria is the most prominent producer in Western and Central Africa, at 4.59%, while Iran leads production in the Middle East and North Africa (2.02%). Another 45 countries in Africa and the Middle East contributed to less than 1 % of the total research output (Table 2 ). Among the most productive countries (> 100 documents), Iran, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa present the lowest degree of international collaboration and the highest participation as first authors. Many of these show values of international collaboration that exceed 90%, with participation as first author under 30%. This situation is similar or even more pronounced in most low-producing countries (Table 2 ).

Generally speaking, African research output on HIV/AIDS is characterized by its cooperative links, particularly with the USA, UK, and other European countries (75 to 93% of the collaborations). However, South Africa also stands out for its intraregional ties, and it has become the main reference for research collaboration on HIV/AIDS, both in Eastern and Southern Africa and among the top 10 most productive African countries. It has collaborated with 34 different countries, led 41.44% of the collaborations, and participated in 35.76% of the papers led by other African countries. Uganda ranks second in terms of collaborative leadership within Africa, albeit with values that are much more modest, having led 14.06% of its collaborative research and participated in 11.11% of papers led by other African countries. The rest of the countries contribute less than 10% to the total collaborative links established. Except for South Africa, Uganda, and a few other countries like Zimbabwe, the collaborative links between different countries in Africa are few and far between, constituting weak and sporadic ties (Table 3 ).

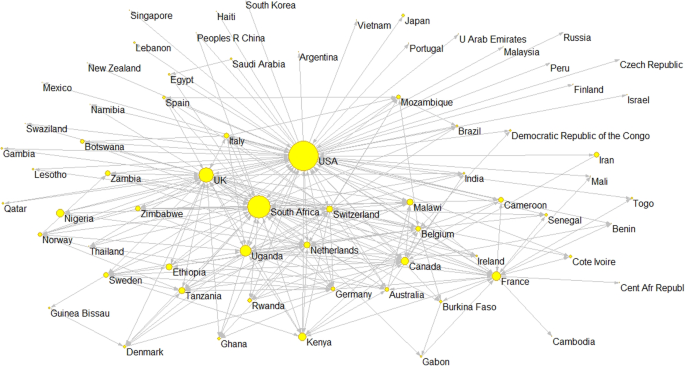

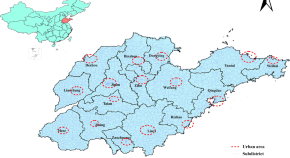

Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the collaboration network. The USA is in the center as the main reference for international collaboration on scientific output on HIV/AIDS, while the UK, Canada, and other European countries like France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Belgium also occupy prominent locations. South Africa is the main African reference for HIV/AIDS publications, reflecting not only its collaborations with the USA, Canada and the European countries but also its prominent role in intraregional collaborations.

International collaboration network of research papers on HIV/AIDS with African and Middle Eastern countries (2010–2017)

Subject areas addressed in publications on HIV/AIDS in Africa and the Middle East

The correlation analysis on scientific HIV/AIDS output, produced by all countries worldwide, by African countries alone, and through Africa+global collaborations, shows differences in disciplinary orientations and research topics. In terms of disciplines involved, the lowest degree of correlation pertains to global publications versus solely African publications (k = 0.73; Table 4 ). There is also certain discordance between solely African publications and Africa+global collaborations (k = 0.79). In contrast, there is great affinity between global research output and output from Africa+global collaborations (k = 0.97). Of note, HIV/AIDS publications from Africa alone was dominated by papers in the field of “Public, Environmental & Occupational Health,” while the disciplines of “Infectious Diseases” and “Immunology” occupy the first rankings both globally and in African+global collaborations. The disciplines of “Medicine, General & Internal” and “Health Policy & Services” were also of great relevance in the publications from African countries alone (Table 4 ).

Our comparison of the MeSH qualifiers revealed similar disparities (Table 5 ). The lowest degrees of correlation were between global versus solely African research output (k = 0.68) and between global versus Africa+global collaborations (k = 0.69). However, there was a high degree of correlation between solely African publications and Africa+global collaborations (k = 0.97). With regard to the most prominent MeSH qualifiers, epidemiological studies occupy the top spot in both global and solely African publications. However, “Drug therapy” and “Therapeutic use” are more popular orientations in solely African publications than “Inmmunology,” “Genetics,” and “Metabolism” (Table 5 ).

Finally, with regard to MeSH descriptors, publications from Africa and the Middle East reflects the high prioritization of terms related to prevalence and treatment approaches (Table 6 ). Furthermore, global scientific production on HIV/AIDS suggests gender parity in terms of the research focus (both the “Male” and “Female” terms were assigned to 55% of the documents). However, for publications produced by researchers from solely African countries, the “Female” term is present in 73.38% of the documents, and for publications produced by Africa+global collaborations, this MeSH appeared in 76.71% of the documents.

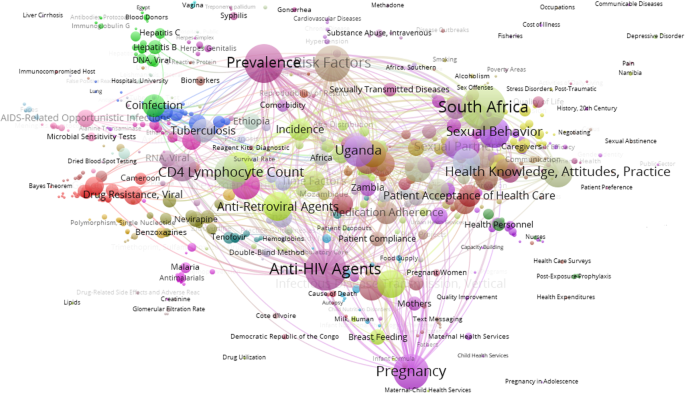

Figure 3 presents a visualization of the main MeSH terms used to represent Africa and Middle East HIV/AIDS research topics and the links between them. Overall, studies that analyze anti-HIV agents, prevalence, and risk factors constitute the main subject areas that articulate the research. Incidence and its relation to sexual behaviors and health education (knowledge, prevention, acceptance of treatment for the disease) is also an important topic, as is research on pregnancy, maternal health, and prenatal care. Other relevant areas focus on co-infection (with tuberculosis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, meningitis), resistance to anti-viral agents, and the use of certain medicines to treat the infection (lamivudine, tenofovir etc.).

MeSH co-occurrence network on HIV/AIDS research papers from African and Middle Eastern countries (2010–2017)

Growth, visibility, and concentration of scientific production

Our analysis shows that scientific production on HIV/AIDS is still dominated by researchers from North America and Western and Central Europe, which together participated in 82% of the documents analyzed, although just 6% of people with HIV live in these regions. In contrast, researchers from countries in Africa and the Middle East participated in less than a quarter of the research papers on HIV/AIDS published between 2010 and 2017 (22%), although two-thirds of all people who are infected with the virus live there. Nevertheless, in relation to previous studies analyzing HIV/AIDS publications produced by researchers from African countries, our results indicate two highly relevant trends: (a) the notable growth in scientific production on HIV/AIDS in this region and (b) the elevated participation in scientific publications with greater visibility and international impact. In absolute terms, the number of documents we identified are double those reported by Macías-Chapula & Mijangos-Nolasco [ 8 ], based on their analysis of HIV/AIDS literature from sub-Saharan Africa included in the National Library of Medicine from 1980 to 2000, and by Uthman [ 9 ] analyzing scientific production on HIV/AIDS from sub-Saharan Africa and indexed in PubMed from 1981 to 2009.

At a country level, the advances made in research are even more significant. In their study on HIV/AIDS literature included in the National Library of Medicine, Onyancha & Ocholla [ 10 ] reported negligible contributions from Uganda and Kenya in the form of journal articles published from 1989 to 1998 ( n = 11 and n = 16, respectively). Our results show that these two countries have now become the second and third most productive on the continent, with a high number of contributions to journals indexed in the WoS-CC ( n = 1921 documents from Uganda and n = 1586 in Kenya). Uthman [ 11 ] studied HIV/AIDS research production from Nigeria between 1987 and 2006, identifying 254 articles in the WoS databases. Our findings, of 679 documents, nearly triple that number, even though the study period is substantially shorter. In South Africa, the production we identified from 2010 to 2017 ( n = 6063) is close to that reported by Uthman [ 9 ] for the entire period from 1981 to 2009 ( n = 8361).

Our results also show a trend toward greater research concentration, with an increase in the relative weight of high-producing countries (particularly South Africa, Uganda, and Kenya), which stand out as the main references for African scientific production on HIV/AIDS. Indeed, these countries now account for over half of all publications from Africa, and their relative contributions are trending upward. Thus, while Uthman [ 9 ] reported that South Africa participated in 34% of the HIV/AIDS publications produced by sub-Saharan Africa, in our results this figure stands at 43%. Similarly, the relative weight of Uganda and Kenya (the second and third most productive countries) has risen from 8 and 7% of the total contributions, respectively, to 14 and 11%. Similar observations have been made in other research fields [ 14 ] and particularly in the biomedical area [ 15 , 16 ], demonstrating that economic development and investments in research constitute key factors explaining the rise in scientific productivity [ 17 ].

The trend toward a greater concentration of research production in a few countries indicates the need to develop policies that facilitate a greater integration of lower-producing and less-developed countries in research activities. The literature describes some measures to stimulate research in these countries that go beyond economic investments, including training and retaining experienced researchers and fostering long-term partnerships based on equitable collaborative research ties. These strategies can enable researchers from these countries to acquire the methodological skills they need and can favor their leadership in spearheading or directing the research [ 13 ].

More specifically to the field of HIV/AIDS, Uthman [ 9 ] analyzed the factors associated with scientific productivity on HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. His results showed that the number of people living with HIV and the number of indexed journals published in the country were predictive of an increase in publications. Other relevant factors include national scientific policies related to countries’ research agendas for this area, plus the adequate integration and participation in the system for publication and dissemination of scientific knowledge. These variables are more closely associated with scientific productivity on HIV/AIDS than others like the number of higher institutions or the number of physicians. The fact that South Africa is the country with the highest number of HIV-positive people and that this subject area has become a priority on the national research agenda [ 18 ] is clearly related to the country’s high research productivity in the field. Its economic growth has complemented this boost; together with other BRICS countries, especially China and Brazil, South Africa has laid the groundwork for development by strengthening its educational, healthcare, and social systems [ 19 , 20 ]. Increased investments in research go hand in hand with this strategy, including through establishing collaborative links with the most advanced economies at a scientific level [ 21 , 22 ]. However, as Adams et al. [ 23 ] signaled in their study, a myriad of factors affect scientific productivity and collaboration in African countries apart from structural factors like the level of economic growth or population size. For example, countries in the Commonwealth sphere, mostly situated in Eastern and Southern Africa and using English as a second language, generally present a higher level of scientific production and collaborative research than other African countries, like those in the Francophone community [ 16 ]. Our results are consistent with this trend: 10 of the 12 most productive countries are linked with the Commonwealth.

Although some countries like Nigeria or Ethiopia have made important research efforts, with corresponding increases in their scientific productivity, different studies have highlighted the need for increasing ties with neighboring countries. This would enable a more fluid exchange of knowledge and experience and foster research in key areas like detection and treatment [ 11 , 24 ].

High degree of international collaboration, low level of leadership

The two main bibliometric features we observed to be associated with HIV/AIDS research activity in Africa were: (a) a high degree of international collaboration with countries from other geographical regions, dominated by the USA and Europe (81% of the documents) and (b) a low level of research leadership, as seen through the low participation of African investigators as the first authors of documents produced in collaboration (20 to 38% among the top 10 most productive countries).

These two features may reflect a certain scientific dependence and subordination among African countries in relation to more developed countries. Moreover, the same situation has been observed in other biomedical research fields that are of special importance to the global South, like tropical diseases, infectious diseases, and pediatrics [ 22 , 25 , 26 ]. More specifically, Kelaher et al. [ 27 ] analyzed randomized controlled trials in the fields of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis that were undertaken in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from 1990 to 2013, identifying three relevant features associated with research leadership. First, there was a much higher proportion of first authors from LMICs in studies funded by LMICs (90%) than in studies funded by the USA (32%). Second, participation as first authors from LMICs was sensibly lower in the field of HIV/AIDS (33%) than for other diseases like malaria (67%). Finally, among first authors from all LMICs worldwide, those from Africa authored fewer papers than those from other regions like Latin America or Asia.

The literature describes different barriers that hinder researchers in LMICs from assuming leadership roles. Some of these are related to the absence of infrastructures or adequate financing [ 28 ]. Without an established institutional framework, stable research groups cannot be created or sustained; researchers cannot access the technical and financial support they need to submit research tenders; and coordination and monitoring of research priorities in relation to local research agendas is inadequate [ 13 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Other barriers have to do with deficits in methodological skills (like research design and statistical interpretation) or language (composition of articles or fluency in English). All of these factors can affect researchers’ capacity to lead studies and authorship [ 32 , 33 , 34 ].

At the same time, there are structural factors related to the hub-and-spoke model that favor the increased recognition and success of countries conducting mainstream research. Economic and human resources are concentrated in North America and Europe, and these regions also establish priority research topics. Editorial bias and the Matthew effect of accumulated advantage cement the structural forces perpetuating the under-representation of researchers from the global South from assuming positions of leadership in scientific publications [ 26 , 32 ].

The two countries constituting the axis of the collaborative research network on HIV/AIDS are the USA and South Africa. The former stands out for the high number of collaborative links it has established, with its researchers co-authoring papers with most African and Middle Eastern countries (52 countries). In total, 7693 collaborative ties (co-authored papers) were established in the study period, 70% of which were led by researchers in American institutions. Other bibliometric studies have also described the relevance of the USA in collaborative HIV/AIDS research output in Africa [ 11 ], Latin America and the Caribbean [ 35 ], and Asia [ 36 ]. Our own group have highlighted this role in other biomedical research fields [ 37 ].

For its part, South Africa is clearly the country of reference for HIV/AIDS research activity on the African continent, with a quantitative weight that is well above that observed in other biomedical areas in which it also exercises leadership. Nachega et al. [ 16 ] assessed the participation of African countries in publications on epidemiology and public health in the WoS databases, reporting that South Africa was represented in 22% of the documents, Kenya in 10%, and Nigeria in 9%. In our study, 41% of the documents on HIV/AIDS were authored by researchers in South Africa. This country, along with Ethiopia, is also notable for its leadership, figuring in the affiliations of 38% of the first authors. A similar phenomenon has also been observed in other fields of the health sciences, such as infectious diseases [ 15 , 38 ].

In addition to maintaining important collaborative ties with the USA and different European countries [ 39 , 40 ], South Africa has also emerged as a hub for intraregional collaborations within Africa. It has established links with 35 countries—far more than other African countries. Indeed, it is the main collaborator for all the other African countries in the top 10 for HIV/AIDS research productivity, even though these collaborations represent just 12% of the total collaborations in which South Africa participates. In that sense, some papers have called for BRICS countries, including South Africa, to increase their efforts to tackle the challenges primarily affecting the developing world [ 19 ]. In the case of South Africa, this could be done by promoting intraregional collaborations in sub-Saharan Africa, as research undertaken at a local level has the most potential to produce benefits, both for population health and socioeconomic development [ 20 , 41 ]. Hernandez-Villafuerte, Li & Hofman [ 42 ] analyzed collaborations among sub-Saharan countries conducting economic evaluations of healthcare interventions, reporting results consistent with ours: researchers in this region tend to collaborate more with Europeans and North Americans than with each other.

The literature highlights specific barriers impeding equitable research collaboration for African researchers, for example the paper by Okeke [ 43 ], who pointed to the limited duration of research programs, which should be longer in order to nurture stable collaborations that build hard and leadership capacities. In addition to infrastructure, other aspects mentioned include managerial expertise, administrative capabilities, and the capacity to improvise at African partner institutions. In the same line, Boum II [ 44 ] and Boum II et al. [ 45 ] discuss the difficulties in harmonizing conflicting interests between Western and African countries, making it essential to prioritize financing for equitable initiatives that lay out specific goals and expectations for partnerships, or which promote initiatives like mentorship programs and investment in Africa-based researchers that strengthen institutional capacity.

Some examples of successful collaborations for promoting equitable research partnerships and African leadership in HIV research include initiatives like the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH) in Kenya, the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) consortium, and different initiatives coordinated and driven by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) or the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), among others.

Research interests in public health, epidemiology, and treatment approaches

HIV/AIDS research produced by solely African countries differed from global research in terms of disciplinary and subject area orientations, with a greater focus on public health, epidemiology, and treatment. This finding indicates the need to consider regional, national, and local specificities and interests when determining research priorities. In fact, numerous studies have already signaled the poor alignment between the priorities laid out in African countries’ national research agendas and the research topics that are actually financed [ 12 , 16 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ].

From a public health perspective, for example, Uthman [ 11 ] pointed out the need for further research evidence to inform HIV prevention and control programs. In this field, some countries perform better than others: South Africa is particularly strong in public health research [ 50 ], while other African countries and regions, such as French Africa, have made limited contributions [ 51 ].

Studies on epidemiology and treatment approaches for HIV/AIDS are very relevant for research produced in Africa, in contrast to what occurs on a global scale, where these orientations have a relatively limited weight. Nachega et al. [ 16 ] pointed out that research on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria have become the main research topics addressed in epidemiological and public health publications in African countries. However, these authors argued for moving epidemiology and public health research beyond the limited sphere of communicable disease control in order to address the regional impact of non-communicable diseases, for example in maternal and child health. This is especially relevant in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, where epidemiologists are overwhelmingly deployed to control infectious diseases, especially HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. The study also calls for strengthening regional expertise in epidemiology in order to shed light on the underlying causes of ill health, rather than to merely control infections and outbreaks [ 16 ].

In addition to epidemiological studies, African research also reflects an intense interest in drug therapies for HIV/AIDS, illustrating that control of the infection is a priority for research agendas and policies in African countries [ 12 ].

More specifically, previous literature on HIV/AIDS research has shown a greater focus on women in studies carried out with the participation of African researchers [ 10 ]. Our study confirms this finding: 73 to 77% of the documents investigated women, compared to 55% in the global literature. One possible explanation for this includes the fact that women are more biologically, economically, socially, and culturally vulnerable to infection. Indeed, for every 10 African men who are HIV-positive, there are 12 to 13 infected women; moreover, 55% of adults who acquire HIV are women, with profound implications for mother-to-child transmission [ 10 ]. In consonance with this fact, a greater number of women participate and work on HIV care programs in Africa, and a large proportion of the clinicoepidemiological investigations in these settings are based on care program data [ 52 ].

The different epidemiological patterns of HIV/AIDS transmission in North America and Western and Central Europe must also be taken into account, that motivate a greater interest of research in these regions on sexual transmission between men and intravenous drug users. These epidemiological patterns are less important in Africa [ 53 ]. The presence in the MeSH co-occurrence network of the descriptors “pregnancy” and “sexual behavior” are noteworthy, reflecting how African researchers are investigating aspects like maternal-fetal transmission of HIV [ 54 ] or knowledge and prevention of sexual risk, and changing the preconceptions that still persist about the social determinants of transmission [ 47 ]. The prominence of topics related to preventing mother-to-child transmission stands in contrast to the near absence of topics related to children and young people. These groups are especially sensitive to the physical and psychosocial impacts of HIV and AIDS, indicating the need for increased research on young people who are at risk of or living with HIV [ 55 ].

The greater research attention to topics related to public health, epidemiology, and treatment may also respond to limited laboratory capacity, which is needed for virologic, immunological, and basic research. In that sense, it is essential to promote initiatives that strengthen these research structures and capacities in African countries, rather than only supporting programs and projects on preventive and clinical approaches.

Limitations and future lines of research

Limitations of the present study include the fact that a considerable portion of HIV/AIDS research in African countries is disseminated using document types and media that we did not consider, such as meeting abstracts and journals that are not indexed in the WoS-CC. Moreover, using the MeSH thesaurus from the field of health sciences could have resulted in an underestimation of research spheres related to our subject area, such as research in the social sciences. In that sense, some papers have indicated that stigma and discrimination still constitute the main barriers to controlling HIV/AIDS [ 56 ]. The process used to assign geographic place variables to the papers included in the sample was based on authors’ stated institutional affiliation; this method has the inherent limitation of not being able to measure the author’s origin, nationality, or identification with the country, but rather the institution’s (and the country’s) capacity to generate outputs in the form of scientific publications. Thus, many researchers of African origin who work at institutions in the USA and Europe would be coded as US/European researchers. Furthermore, the use of first author status as a proxy for African leadership may be misleading, as an African senior author may be the last author on a publication or may have played a leadership role in some aspects other than the manuscript preparation.

Our study focused on obtaining macro indicators on scientific collaboration and output by regions and countries. Future lines of research could conduct meso- or microlevel analyses, for example focusing on the participation of institutions or authors in African HIV/AIDS research or on the impact of the publications. It would also be of great interest to identify the organisms or programs that have funded the research inspiring the publications about HIV, measuring resource contributions according to domestic versus international as well as public versus private origins.

The main conclusions of our study are as follows.

1. Our results reflect significant progress in African-produced HIV/AIDS research, at both a quantitative level (with notable increases in the number of publications) and qualitative level (through participation in journals indexed in a bibliographic database that brings together the most high-impact and high-visibility international publications). Despite these advances, however, scientific output is still concentrated in a small number of countries, chief among them South Africa, while other countries in Africa and the Middle East make only negligible contributions, despite the high burden of HIV infections.

2. The participation of African countries conducting HIV/AIDS research is characterized by a dependence on and subordination to the USA and European countries. Collaborations between these regions reflect limited leadership by African countries, as measured by the participation of African researchers as the first authors of published studies.

3. HIV/AIDS research conducted with participation from African countries shows appreciably different disciplinary and subject-area interests than global HIV/AIDS research, with a stronger focus on public health, epidemiology, and drug treatments.

It is essential to promote balanced North-South research that properly addresses the most acute needs and gaps in the places where HIV/AIDS has the largest impact. To achieve this balance, it is necessary to transfer research skills to African partners, promote equitable collaborative ties, and empower African countries, especially those with less scientific activity and more disease prevalence. In the same way, the lack of investment in research infrastructure by African governments likely makes it more difficult for African investigators to lead their own research. Intraregional collaborations among African countries can also help to avoid the further concentration of research capacity, reproducing the global North-South model on the African continent.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RJMAY5 .

GBD 2015 HIV Collaborators. Estimates of global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and mortality of HIV, 1980–2015: the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e361–87.

Galvani AP, Pandey A, Fitzpatrick MC, Medlock J, Gray GE. Defining control of HIV epidemics. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e667–70.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

UNAIDS Data 2018. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf . .

Fajardo-Ortiz D, López-Cervantes M, Duran L, Dumontier M, Lara M, Ochoa H, et al. The emergence and evolution of the research fronts in HIV/AIDS research. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178293.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

González-Alcaide G, Salinas A, Ramos JM. Scientometrics analysis of research activity and collaboration patterns in Chagas cardiomyopathy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006602.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Macias-Chapula CA, Rodeo-Castro IP, Narvaez-Berthelemot N. Bibliometric analysis of AIDS literature in Latin America and the Caribbean. Scientometrics. 1998;41:41–9.

Article Google Scholar

Sengupta IN, Kumari L. Bibliometric analysis of AIDS literature. Scientometrics. 1991;20:297–315.

Macías-Chapula CA, Mijangos-Nolasco A. Bibliometric analysis of AIDS literature in Central Africa. Scientometrics. 2002;54:309–17.

Uthman OA. Pattern and determinants of HIV research productivity in sub-Saharan Africa: bibliometric analysis of 1981 to 2009 Pubmed papers. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:47.

Onyancha OB, Ocholla DN. A comparative study if the literature on HIV/AIDS in Kenya and Uganda: a bibliometric study. Libr Inf Sci. 2004;26:434–47.

Uthman OA. HIV/AIDS in Nigeria: a bibliometric analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:19.

Mugomeri E, Bekele BS, Mafaesa M, Maibvise C, Tarirai C, Aiyuk SE. A 30-year bibliometric analysis of research coverage on HIV and AIDS in Lesotho. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:21.

Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, Ntakiyiruta G. Building research capacity in Africa: equity and global health collaborations. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001612.

Tijssen R. Africa’s contribution to the worldwide research literature: new analytical perspectives, trends, and performance indicators. Scientometrics. 2007;71:303–27.

Uthman OA, Uthman MB. Geography of Africa biomedical publications: an analysis of 1996–2005 PubMed papers. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6:46.

Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Ho Y-S, Lo M, Anude C, Kayembe P. Current status and future prospects of epidemiology and public health training and research in the WHO African region. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1829–46.

Rahman M, Fukui T. Biomedical research productivity: factors across the countries. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:249–52.

Dwyer-Lindgren L, Cork MA, Sligar A, Steuben KM, Wilson KF, Provost NR, et al. Mapping HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa between 2000 and 2017. Nature. 2019;570:189–93.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bai J, Li W, Huang YM, Guo Y. Bibliometric study of research and development for neglected diseases in the BRICS. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:89.

Sun J, Boing AC, Silveira MPT, Bertoldi AD, Ziganshina LE, Khaziakhmetova VN, et al. Efforts to secure universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment: a comparison of BRICS countries. J Evid Based Med. 2014;7:2–21.

Bornmann L, Wagner C, Leydesdorff L. BRICS countries and scientific excellence: a bibliometric analysis of most frequently cited papers. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2015;66:1507–13.

Article CAS Google Scholar

González-Alcaide G, Park J, Huamaní C, Ramos JM. Dominance and leadership in research activities: collaboration between countries of differing human development is reflected through authorship order and designation as corresponding authors in scientific publications. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182513.

Adams J, Gurney K, Hook D, Leydesdorff L. International collaboration clusters in Africa. Scientometrics. 2014;98:547–56.

Deribew A, Biadgilign S, Deribe K, Dejene T, Tessema GA, Melaku YA, et al. The burden of HIV/AIDS in Ethiopia from 1990 to 2016: evidence from the global burden of diseases 2016 study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2019;29:859–68.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Keiser J, Utzinger J. Trends in the core literature on tropical medicine: a bibliometric analysis from 1952-2002. Scientometrics. 2005;62:351–65.

Keiser J, Utzinger J, Tanner M, Singer BH. Representation of authors and editors from countries with different human development indexes in the leading literature on tropical medicine: survey of current evidence. BMJ. 2004;328:1229–32.

Kelaher M, Ng L, Knight K, Rahadi A. Equity in global health research in the new millennium: trends in first-authorship for randomized controlled trials among low- and middle-income country researchers 1990-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:2174–83.

Zakumumpa H, Bennett S, Ssengooba F. Leveraring the lessons learned from financing HIV programs to advance the universal health coverage (UHC) agenda in the east African community. Glob Health Res Policy. 2019;4:27.

Feldacker C, Pintye J, Jacob S, Chung MH, Middleton L, Iliffe J, et al. Continuing professional development for medical, nursing, and midwifery cadres in Malawi, Tanzania and South Africa: a qualitative evaluation. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186074.

Nchinda TC. Research capacity strengthening in the south. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1699–711.

Wight D, Ahikireb J, Kwesigac JC. Consultancy research as a barrier to strengthening social science research capacity in Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2014;116:32–40.

Langer A, Díaz-Olavarrieta C, Berdichevsky K, Villar J. Why is research from developing countries underrepresented in international health literature, and what can be done about it? Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:802–3.

Smith E, Hunt M, Master Z. Authorship ethics in global health research partnerships between researchers from low or middle income countries and high income countries. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15:42.

Yousefi-Nooraie R, Shakiba B, Mortaz-Hejri S. Country development and manuscript selection bias: a review of published studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:37.

Macias-Chapula CA. AIDS in Haiti: a bibliometric analysis. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88:56–61.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chen TJ, Chen YC, Hwang SJ, Chou LF. International collaboration of clinical medicine research in Taiwan, 1990–2004: a bibliometric analysis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70:110–6.

Ramos-Rincón JM, Pinargote-Celorio H, Belinchón-Romero I, et al. A snapshot of pneumonia research activity and collaboration patterns (2001–2015): a global bibliometric analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19:184.

Badenhorst A, Mansoori P, Chan KY. Assessing global, regional, national and sub-national capacity for public health research: a bibliometric analysis of the web of science in 1996-2010. J Glob Health. 2016;6:010504.

Falagas ME, Bliziotis IA, Soteriades ES. Eighteen years of research on AIDS: contribution of and collaborastion between different world regions. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2006;22:1199–205.