- Open access

- Published: 07 October 2016

Analyzing early child development, influential conditions, and future impacts: prospects of a German newborn cohort study

- Sabine Weinert 1 ,

- Anja Linberg 2 ,

- Manja Attig 3 ,

- Jan-David Freund 1 &

- Tobias Linberg 3

International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy volume 10 , Article number: 7 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

23 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The paper provides an overview of a German cohort study of newborns which includes a representative sample of about 3500 infants and their mothers. The aims, challenges, and solutions concerning the large-scale assessment of early child capacities and skills as well as the measurements of learning environments that impact early developmental progress are presented and discussed. First, a brief overview of the German regulations related to early child education and care (ECEC) and parental leave as well as the study design are outlined. Then, the assessments of domain-specific and domain-general cognitive and socio-emotional indicators of early child functioning and development are described and the assessments of structural, orientational, and process quality of the children’s learning environment at home and in child care are presented. Special attention is given to direct assessments and their reliability and validity; in addition, some selected results on social disparities are reported and the prospects of data analyses are discussed.

Early childhood and early child education are an important basis for later development, educational performance, and pathways as well as for lifelong learning and well-being. This important claim has been made repeatedly (Caspi et al. 2003 ; Noble et al. 2007 ), and even critical phases of development have been suggested (e.g., Mayberry et al. 2002 ). Nevertheless and despite the existence of quite a few longitudinal studies addressing this issue, empirical evidence concerning effective conditions, differential child progress, and how the early phases of life impact future development and prospects is still rare.

From an educational and political point of view, it is alarming that various studies have documented profound disparities in child development according to family background when children are merely 3 years of age (Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997 ; Dubowy et al. 2008 ; Hart and Risley 1995 , 1999 ; Weinert et al. 2010 ). Even in the first year of life, very early roots of social disparities have been demonstrated which increased substantially over the next few years (Halle et al. 2009 ). In addition, some studies show a high stability of interindividual differences and social disparities from age three onward across preschool (Weinert and Ebert 2013 ; Weinert et al. 2010 ) and school age (Law et al. 2014 ). Notably, the stability of individual differences in children’s test performance has been shown to be even more pronounced in educationally dependent domains of development, like language and factual knowledge, than in more domain-general and less culture-dependent facets of children’s cognitive functioning, as indicated by non-verbal intelligence test scores (Weinert et al. 2010 ).

Drawing on a bioecological model of development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006 ), developmental progress and child education are influenced from early on by the interaction between (developing) child characteristics, skills, and competencies and the quality of structural and process characteristics of the learning environment at the child’s home (Bakermans-Kranenburg and van Ijzendoorn 2011 ; Bradley and Corwyn 2002 ; Ebert et al. 2013 ; Weinert et al. 2012 ) as well as in child care (Anders et al. 2013 ). Longitudinal studies shed light on these interactions and how they impact later development and education, which is of great importance for gaining a better understanding of the underlying processes and influential conditions. It is important to note that the form and organization of the various learning environments are affected by state regulations, which differ between countries, resulting in different support systems, offers and regulations for parents from child birth until her/his formal school enrolment (Waldfogel 2001 ).

Regulations in Germany

Maternity leave regulations in Germany prescribe a period of 14 weeks for maternity leave which is divided into two phases: 6 weeks before and 8 weeks after birth. Mothers receive maternity pay from public funds in addition to their employer’s contribution which amounts to 100 % of their former income. After this period, parents are offered various options for taking parental leave until the child’s third birthday. Specifically, parents may interrupt their employment to provide child care and are legally protected from dismissal during this 3-year period; parents also receive parental pay during their parental leave (substitution of income) amounting to two-thirds of her/his prior salary (ranging from € 300.- up to € 1800.-) for a maximum period of 14 months.

Governments also support families through child care policies. The German early child education and care (ECEC) system covers institutional care and education before and alongside elementary and secondary school. Since 1993 children from age of three onward have had a legal right to institutional child care which is primarily organized by local communities and welfare organizations providing care to mainly age-mixed groups at centers with varying opening hours (Linberg et al. 2013 ). However, during the last decade, there has been growing demand for ECEC for children under the age of three that led to the enactment of laws on the demand-driven expansion of child care (“Tagesbetreuungsausbaugesetz TAG”) and the expansion of child care infrastructure for infants and children (“Kinderförderungsgesetz KiföG”) in 2005 and 2008, respectively. Additionally, the legal right to institutional ECEC was expanded in 2013 to include 1-year-old children and political leaders from local, state, and federal levels agreed to provide enough places for 35 % of the children.

Accordingly, the actual use of child care for young children under the age of three has rapidly changed during recent years: Within 8 years (2005–2013), the child care rates for the under 3-year olds increased from 7 to 23 % in the Western states of Germany and from 36 to 47 % in the Eastern states, which have their own distinct tradition and infrastructure concerning early care and education (Kreyenfeld and Krapf 2016 ). In 2015, the nation-wide care rate amounted to 32.9 % with mean values of 28.2 % for the Western and 51.9 % for the Eastern states (Statistisches Bundesamt 2016 ).

However, despite rising rates of early education, a child’s family still is the first and often only environment for developmental processes during the first years of life. Thus, there is a substantial need for analyzing the decision mechanisms as well as the effects of the various options available for early child care.

To summarize, longitudinal studies that provide a basis for analyzing the conditions which significantly contribute to early developmental progress are of great importance for the individual child as well as for society. These studies produce relevant knowledge on how children’s abilities, skills, and competencies develop based on individual resources and conditions; how learning opportunities influence their development in different contexts; how disparities emerge early in life; and how all this impacts educational careers, lifelong learning, well-being, and participation in society.

The German National Educational Panel Study

(NEPS) Footnote 1 has been set up to substantially contribute to these issues (Blossfeld et al. 2011 ). The idea of a multicohort panel study was brought up by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). A nation-wide interdisciplinary scientific network of researchers was established to develop this idea further and to prepare a proposal for a longitudinal representative large-scale educational study to investigate, monitor, and compare competence development and educational processes in Germany. In light of the specific challenges associated with sampling and measurement of early child characteristics, a newborn cohort study was not initially included in the main NEPS program, but was planned to be conducted as an associated add-on project. However, the study was incorporated into the NEPS study design on behalf of the international evaluation committee organized by the German Research Foundation (DFG) for two main reasons: the growing research on the importance of early child development and education and the rapid changes taking place in early child care, including new social policies being implemented in Germany (see above).

The NEPS is carried out by a network of excellence. It features a longitudinal multicohort sequence design and comprises more than 60,000 target persons as well as 40,000 context persons. In particular, the NEPS design encompasses six longitudinal panel studies conducted simultaneously, which cover a wide range of ages and educational stages. NEPS data are disseminated in a user-friendly way to the scientific community. According to the sensitivity of data, the access is given by a web download, a remote access solution, or on-site in a secure environment. All data are documented in English and are available for use by national and international researchers. In addition to providing substantial analyses of the data themself, it can be used as a benchmark for intervention research, international comparison, and for evaluating issues such as the differences and changes in the use of institutional child care.

At the moment, more than 1100 researchers from more than 700 projects are drawing on the NEPS data already published. The data are used for research in a variety of scientific disciplines and also for educational monitoring—especially, the indicator-based National Report for Education. In order to facilitate access to results for a wide range of professions interested in education—including policy, administration, and practice—scientific papers with important conclusions and empirical evidence are currently summarized by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) for public communication and information beyond science and are distributed via the NEPS webpage. Moreover, results are regularly fed back to these groups by presentations and newsletters.

The present paper provides an overview of the NEPS newborn cohort study and its analytic potential. First, the design of the study will be presented with a special emphasis on the aims, challenges, and solutions for the assessment of child characteristics and learning environments. We will then report a few selected results (a) concerning the validity and reliability of the measures used and (b) on early social disparities.

Design of the newborn cohort study of the NEPS: a brief overview

Like all other cohort studies of the NEPS, the cohort study of newborns addresses five research perspectives (Blossfeld et al. 2011 ). Drawing on a theoretical framework, various domain-specific as well as domain-general indicators of early child capacities, characteristics, and developments are assessed as well as measures of structural and process characteristics of their (different) learning environments and their social, occupational, and educational family background. In addition, there is a special focus on families with a migration background, on educational decisions (e.g., concerning child care), and—especially in the newborn cohort study—on patterns of coparenting and child care arrangements. By combining direct observational measures, interview data, and questionnaires, the newborn cohort study allows for in-depth analyses of developmental progress and influential conditions that affect the development of educationally relevant competencies and the stability or changes of interindividual differences. Therefore, it provides insight into the mechanisms through which social disparities emerge, change, and impact children’s future prospects and returns to education.

Sampling strategy

To ensure a representative sample, a two-stage procedure was implemented: 84 German municipalities were used as primary sampling units, explicitly stratified according to three strata of urbanization (via the number of inhabitants; see Aßmann et al. 2015 ). Within these municipalities, addresses were sampled and divided into two birth tranches (infants born between February and April 2012 and between May and June 2012) in order to guarantee a small age range for the infant sample. Starting from a gross sample of about 8500 families, a total of about 3500 families (response rate 41 %) took part in the first assessment wave. In the second wave, the realized sample still included about 2850 families (panel stability 83 %).

Assessment waves and data collection

During the very early phases of child development, three successive assessment waves were carried out when children were on average 7 months (wave 1), 17 months (wave 2), and 26 months of age (wave 3). In the first and third wave video-taped observations and computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) were conducted at the family’s home for the entire sample. In the second wave, families were surveyed by computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI), while video-taped observational measures at the child’s home were only assessed in half of the sample (subsample approx. 1500) in accordance with the study’s design. After wave 3 (i.e., from age two onward) children and their context persons were and will be surveyed every year. Data are collected by trained interviewers. Mothers are the primary respondents, as they can provide valid information about conditions and feelings during and after their pregnancy. Each assessment wave is preceded by a longitudinal pilot study, which runs 1 year before the main study is conducted, to test all instruments and procedures.

Measuring early child characteristics: aims, challenges, and solutions

The assessment of a child’s capacities, characteristics, and early development is pivotal for analyzing the effects of environmental conditions and the impact of early child development and education on later development, educational achievement, career, and life satisfaction or other outcomes and returns. In particular, measuring child characteristics is essential to the modeling of intra-individual progress and changes in interindividual differences, including the emergence of social disparities in various domains of development across childhood. At the same time, it is crucial for analyzing the mechanisms of change, the effects of learning environments and opportunities, and their interactions with the individual capacities and characteristics of the children, while taking the risk or protecting factors of the individual child and his/her environment into account, as well as for controlling for basic interindividual differences if necessary.

However, measuring early child characteristics is a major challenge for longitudinal studies, especially large-scale studies. This is due to various issues and questions, such as which aspects and indicators of early child development should be assessed, how should they be measured, and how can the standardization and validity of measurements be ensured in large-scale assessments of very young children.

Early child development: domain-specific challenges for the child

Developmental psychology has convincingly documented for a long time that neither the development of children nor the development of infants is a homogeneous endeavor. Since the time of Piaget’s ( 1970 ) overarching stage theory of development, it has been empirically demonstrated that development is domain-specific, i.e., demands, prerequisites, effective environmental stimulations differ according to the developmental domain under study (e.g., the acquisition of language, of mathematical competencies, of competencies in natural science, or of an intuitive psychology) (Karmiloff-Smith 1999 ). Even in infancy domain-specific precursors of e.g., mathematical and psychological knowledge and competencies are observable (Goswami 2008 ). Determining how educationally relevant competencies emerge from the interplay of these domain-specific precursors and domain-general basic capacities of the child (like basic reasoning abilities, speed of information processing, or executive functions including cognitive flexibility, inhibition, working memory) on the one hand and of the environmental conditions in the family and in child care on the other is an important issue to be addressed by educational studies. It is important to note that (interindividual differences in) basic capacities also change with age and environmental conditions, although not to the same extent as culture- and education-dependent competencies, and that stimulation of and progress in one developmental domain may enhance, hinder, or compensate for those in other domains.

General NEPS framework for assessing competencies

Within the NEPS, a general framework for assessing educationally relevant abilities and competencies has been developed (Weinert et al. 2011 ). Specifically, the assessments include (a) domain-general cognitive abilities/capacities captured by the constructs of “fluid intelligence” (Cattell 1971 ) or “cognitive mechanics” (Baltes et al. 2006 ); these refer to performance differences in speed of basic cognitive processes, the capacity of working memory, and the ability to apply deductive or analogical thinking in new situations (Brunner et al. 2014 ); (b) domain-specific cognitive competencies, e.g., language competencies, mathematical competencies, and natural science competencies are to be assessed longitudinally and as coherently as possible; and not least (c) meta-competencies, including self-regulation (in the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional domain) and socio-emotional competencies are to be measured (see Weinert et al. 2011 for an elaborated rational of the assessments).

Selecting and measuring relevant and predictive indicators of early child development: a challenge for research

As already mentioned, even in infancy and early childhood, there is no overall indicator for children’s capacities and development. Considering the fact that there are thousands of studies into infant competencies, the indicators have to be carefully selected—not least because of the limited study time and other constraints associated with large-scale assessments, especially those concerning infants and young children who cannot be tested in group settings and whose attentional capacities are still limited. Within the NEPS, the selection draws on the general framework outlined above, including domain-general basic capacities, domain-specific precursors and early roots of language and mathematics as well as indicators of socio-emotional development and early self-regulation.

However, deciding on how to measure these early child characteristics and developments is a major challenge for theoretically sound educational large-scale assessments. Just relying on parents’ reports is problematic since the parents’ judgements might be affected, for example, by their (different) knowledge of child development, by possible restrictions/differences in how they observe the child, and by their particular cultural and individual beliefs and biases. In addition, major aspects of domain-general and domain-specific cognitive functioning and development are not easily observable and need sophisticated assessment methods developed in infancy research.

If newborn cohort studies took direct measures into consideration in addition to interviews and questionnaires, they often relied on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley 2006 ; Schlesiger et al. 2011 for a brief overview). However, the NEPS feasibility and pilot studies revealed that the standardized administration of test items (using an educationally sound selection of items) turned out to be highly error-prone for trained interviewers who are usually experts in administering interviews but not tests. In addition, the sensorimotor indicators of developmental status measured by the Bayley Scales have been shown to be rather instable across situations (Attig et al. 2015 ) and infancy (McCall et al. 1977 ) and were hardly predictive for later cognitive functioning (e.g., Fagan and Singer 1983 ). Therefore, an indicator of basic information processing abilities was introduced within the NEPS newborn cohort study which has predominantly been used in baby lab studies, namely, the children’s visual attention and speed of habituation within a habituation–dishabituation paradigm. Within this paradigm, the child’s visual attention and the decrease of her/his visual attention when being presented with a series of identical or categorically similar stimuli are used as indicators of the child’s ability to build up a cognitive representation of a stimulus or a stimulus category (Pahnke 2007 ; Sokolov 1990 ). In addition, a new stimulus (or a stimulus from a new category) is presented in the dishabituation phase of the paradigm and a new increase of the child’s visual attention is interpreted as a signal of her/his ability to distinguish stimuli or categories presented during the two phases of the paradigm and to show a preference toward new information. These measures have been shown to be highly predictive of later intelligence scores or other indicators of cognition and language (Bornstein and Sigman 1986 ; Fagan and Singer 1983 ; Kavšek 2004 ). Thus, this paradigm was used to assess early domain-general information processing/categorization abilities; it was also used to measure early precursors of numeracy and word learning (see Table 1 ). To assure standardization and reliability, pictures were presented on a computer screen and the child’s looking behavior (look at/away from the respective stimulus) was video-taped (as were all other direct measures) and coded afterward on a 30 frames per second basis. A third direct indicator of early child characteristics relevant to learning and education is her/his interactional behavior (cognitive, behavioral, and socio-emotional aspects) in mother–child interaction (see “ Assessment of mother–child interaction: direct measurement of the home-learning environment and of the child’s characteristics in mother–child interaction ” section). Table 1 summarizes the measurements of child characteristics and development assessed in the first three waves of the NEPS newborn cohort study.

In addition to direct assessment, mothers were asked (see Table 1 ) about the child’s skills and development as well as about the child’s health. The questions on the child’s skills and development cover items on cognition (e.g., means-end task and object categorization), communicative gesture (e.g., to draw someone’s attention, negation/headshaking), gross and fine motor skills (e.g., climbing up steps, stacking of toy blocks) as well as language (e.g., size of productive vocabulary, comprehension of short instructions). A short version of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ-R, Gartstein and Rothbart 2003 ) was used to assess facets of the child’s temperament, specifically orienting/regulatory capacity (items like “if you sing or speak to <target child’s name>, how often does she/he calm down instantly?”) and negative affectivity (items like “when <target child’s name> can’t have what she/he wants, how often does she/he get angry?”) (Bayer et al. 2015 ). In wave 3, a German language checklist and, for bilingual children, an additional Turkish or Russian language checklist (versions of the well-known MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (CDI); Fenson et al. 1993 ) was introduced.

Measuring learning environments: aims, challenges, and solutions

Likewise, measuring learning environments that impact child development is an important challenge for longitudinal large-scale educational studies. As suggested by bioecological theories (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006 ), it is not enough to just focus on the home-learning environment; the use and features of non-parental care and other learning environments like parent–child programs, which 55 % of the children in the newborn cohort study experience in their first year of life, should also be assessed. Moreover, it is not sufficient to only measure quantitative structural characteristics, since domain-general and domain-specific qualitative aspects have been shown to be especially important (e.g., Anders et al. 2012 ; Sylva et al. 2006 ); however, indispensable direct observational measurements are hard to obtain in large-scale studies. It is important to note that the meaningfulness of the specific features/aspects assessed for characterizing the different learning environments and the constraints of the measurements have a large impact on the validity of subsequent analyses and conclusions.

General framework of the NEPS

To deal with these issues coherently across cohorts, the measurement of important characteristics of learning environments draws on a general framework which subdivides three different dimensions: Structural quality , which refers to relatively persistent general conditions; orientational quality , like values, norms, and attitudes of an actor; and process quality , which refers to the interaction of the individual with her/his learning environment (Bäumer et al. 2011 ).

Selection and measurement of indicators

For the assessment of the process quality of the home-learning environment as the central learning environment in the very early years, the NEPS newborn cohort study relies on both interviews/questionnaires and direct observations (see below).

In addition, as approx. 24 % of the children of the newborns’ cohort sample were using supplementary non-parental care settings in wave 2, the dimensions specified above were also surveyed in these child care settings using self-administered drop-off questionnaires for center-based ECEC as well as for child minders. Because the NEPS has to rely on survey data, the validity of the quality of non-parental care settings gained from the questionnaire is tested by conducting a sub-study, which compares observational methods with the questionnaire used in the NEPS study. The questionnaire covers structural characteristics as well as process characteristics (see Table 2 for examples).

Besides external day care, the newborn cohort study of the NEPS places a strong emphasis on the home-learning environment—especially in very early childhood—as it is of central importance for later development (NICHD 1998 ). Large-scale longitudinal studies mostly focus on the structural aspects of the home-learning environment to account for variability in infants’ and toddlers’ cognitive and social skills (Halle et al. 2009 ; Hillemeier et al. 2009 ). However, process variables account for additional variance in both social and cognitive child outcomes and may even mediate the effect of structural characteristics (Flöter et al. 2013 ; NICHD 1998 ). Therefore, the assessment of the home-learning environment is not only limited to measuring structural aspects like sociodemographics, but also includes orientations (see Table 3 ); in particular, special emphasis is given to the assessment of processes . Mothers are asked about issues, such as joint activities and their language use at home and the quality of these interactions is also assessed by means of videotaping mother–child interactions during the first three assessment waves (see Table 3 ; “ Assessment of mother–child interaction: direct measurement of the home-learning environment and of the child’s characteristics in mother-child interaction ” section).

Assessment of mother–child interaction: direct measurement of the home-learning environment and of the child’s characteristics in mother–child interaction

On the one hand, the assessment of mother–child interactions as a dyadic process allows a deeper look into maternal interaction behavior as a crucial characteristic of the home-learning environment; on the other hand, it captures additional information about the relevant characteristics of the child.

The quality of maternal interaction behavior has been shown to impact a child’s language (Nozadi et al. 2013 ; Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2001 ), cognitive (NICHD 1998 ; Pearson et al. 2011 ), and socio-emotional development (Bigelow et al. 2010 ; Meins et al. 2001 ). High-quality maternal interaction behavior in very early childhood is mostly described as interaction behavior that provides the child with emotional support in terms of sensitivity, which is defined as a prompt, warm, and contingent reaction to the child’s needs and signals (Ainsworth et al. 1974 ). But stimulating interaction behavior in the sense of scaffolding behavior (Wood 1989 ) is also regarded as high-quality maternal behavior, even in early childhood.

However, maternal interaction behavior cannot be considered separately from the child’s behavior, as interaction is a dyadic process in which both partners’ behavior refers to each other in a reciprocal way. It is well acknowledged that children play an active role in the dyadic interaction process from the very beginning, initiating interactions (van den Bloom and Hoeksma 1994 ) and influencing their occurrence and appearance (Lloyd and Masur 2014 ). Additionally, the child’s temperament (e.g., fear, excitement, protesting, and crying) can become effective in an interaction (Mayer 2013 ).

Accordingly, the NEPS newborn cohort study assesses maternal as well as filial interaction behavior via observation. The mother–child interactions are videotaped in the family home and are rated afterward by trained coders. The interaction itself takes place in a semi-standardized play situation in which the mother and the child play with a standardized toy set (Sommer et al. 2016 ). The play situation is adapted to the different age-related requirements: In the first wave, the mother–child interaction is videotaped for 5 min in which toys from the NEPS toy set are provided. In waves 2 and 3, the mother and child are observed while carrying out a three-bag procedure in which the mother and child played for 10 min with toys from three different bags in a set order (NICHD 2005 ).

Maternal as well as filial interaction behavior is assessed using a macro analytic rating system whereby various interactional characteristics are evaluated on five-point-rating scales with qualitatively specified graduations ([EKIE]; Sommer and Mann 2015 ). The assessment of maternal behavior covers emotional supportive interaction behavior (like sensitivity to distress and non-distress, positive regard for the child, emotionality) and stimulating interaction behavior, including a common rating for language and play stimulation in the first two waves and differentiating language and mathematical stimulation in wave 3 when children were 2 years of age (see Table 3 ). The mother’s intrusiveness, detachment, and negative regard of the child were also rated. The coding of the child’s behavior and emotions focuses on the child’s mood, activity level, social interest in the mother, and sustained attention to objects.

Some selected results

NEPS data are disseminated among the scientific community for analysis and provide an important basis for substantive longitudinal and comparative research. In particular, the various measurements of child characteristics and the detailed measures of the home-learning environment, including the observation of mother–child interactions, enable in-depth analyses to be conducted. In the first section, the results on the reliability and validity of these direct measures and information on the underlying constructs are given, while the second section contains an analysis of early social disparities in the mother’s behavior and child’s development. In addition to using the data from the newborn cohort study (wave 1), Footnote 2 we also draw on the data obtained from the “ViVA project,” Footnote 3 which aims to validate the NEPS measures as one of its objectives.

Reliability and validity of measures of mother–child interaction

Assessing interactions in a large-scale assessment is challenging with regard to validity and reliability of the measurements and ratings. In the NEPS newborn cohort study, these challenges were solved quite successfully: Weighted inter-rater reliability ranged from 84 to 100 % and the ecologic validity of the observed maternal interaction behavior seems to be high, as the data from the ViVA project show that interaction behavior assessed in the semi-structured play situation is comparable to maternal interaction behavior in other situations, i.e., natural feeding and diapering situations (Friedman test comparing differences between interaction situations: χ 2 = 0.74, p = 0.69; Intra-Class-Correlations of maternal interaction behavior in different situations: ICC = 0.68, p < 0.001; n = 23–30; Vogel et al. 2015 ).

Assessing the quality of the mother’s interaction behavior is a core construct of the home-learning environment in the first waves of the newborn cohort study and focuses on socio-emotional aspects as well as on stimulation. Although the assessed indicators address different aspects of maternal interaction behavior, some of them are related to each other (see Table 4 ). It is worth noting that aspects, like intrusiveness, detachment, or negative regard, are not simply the negative end of the more or less pronounced positive dimensions.

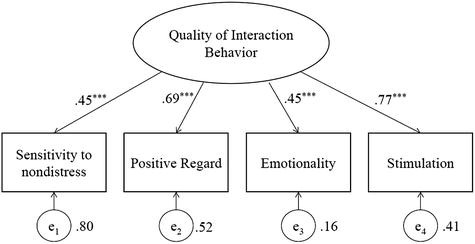

From a theoretical point of view, high-quality interaction behavior includes both sensitivity and stimulation behavior. To test the assumption that a rather broad composite indicator of quality of interaction behavior is not only theoretically but also empirically meaningful, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted (see Fig. 1 ). Items in the socio-emotional domain ( sensitivity to non - distress , Footnote 4 positive regard , and emotionality ) as well as stimulation loaded substantially on quality of interaction behavior (all standardized coefficients above 0.45). Positive regard (0.69) and stimulation (0.77) contributed the most to this factor. Internal consistency was high (Cronbach's α = 0.80).

Results from confirmatory factor analysis for the latent variable Q uality of interaction behavior (Linberg et al. 2016 ). N = 2190; Chi 2 (2) = 16.05, p < .000; RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = .99; based on all German-speaking mother–child interactions in wave 1

One should note, however, that this broad measure of the quality of interaction behavior is only slightly, albeit significantly, related to other aspects of the home-learning environment which were assessed via the parents interview: This includes issues, like the overall amount of joint activities with the child ( r = 0.13, p < 0.000) and special activities (joint picture book reading, r = 0.13, p < 0.000; joint construction play, r = 0.07, p < 0.000; and talking to the child, r = 0.07, p < 0.000).

Reliability and validity of measures of early child characteristics

Given the sample size and household setting, the available data on child characteristics provide a rather detailed insight into the early stages of development, especially with respect to early cognitive capacities and child temperament, which are both measured by multiple indicators. As expected, the first results revealed that these multiple assessment approaches refer to different facets of early child development.

The mother’s report on the child’s temperament deals with the reactions of the child to stressful situations and her/his susceptibility to calming related behavior. In line with previous evidence, this is hardly related to the indicators of child’s temperament, which were assessed in a fairly relaxed mother–child interaction situation ( r = 0.05, p < 0.05; Freund and Weinert 2015 ). At the same time, there is evidence supporting the validity and reliability of these measurements. In the ViVA validation study, the information from the questionnaire has been shown to represent the complete subscales of the IBQ-R from which the items were selected ( r = 0.51 for negative affectivity/0.70 for orienting/regulatory capacity, p < 0.01; Bayer et al. 2015 ). In addition, it is correlated with the children’s reactions to stress-inducing maternal behavior in a still-face-paradigm where the mother is instructed not to react to her child’s signals ( r = 0.34–0.43, p < 0.05; Freund and Weinert 2015 ).

Likewise this can be shown for the assessments of early cognitive capacities/competencies. In the ViVA study, the items on sensorimotor development (assessment of developmental status) were highly correlated with the complete cognition and motor subscales of the Bayley Scales, respectively ( r = 0.48–0.63, p < 0.01; Attig et al. 2015 ). Hence the data on sensorimotor development as well as the data on basic information processing abilities (habituation–dishabituation paradigm; 85 % of the videos codable; non-completion of child <1 %; inter-coder reliability in wave 1: κ = 0.91) both rely on scientifically well-established and successfully applied assessments. Nevertheless, they are hardly correlated with each other and thus seem to cover different aspects of early development ( r = 0.06/0.14, p < 0.05; Weinert et al. 2016 ).

Although the findings always have to be considered within the context in which the assessments were made (e.g., short version/time), the validity of the various measurements of child characteristics and maternal interaction behavior seems to be apparent.

Early roots of social disparities in child development

The data of the NEPS newborn cohort study allow for an analysis of early social disparities with respect to both early child characteristics and their mother’s interaction behavior. Analyses of data from the first assessment wave when children were 6–8 months of age are in accordance with a bioecological model of child development (Weinert et al. 2016 ). As hypothesized, the mother’s interaction behavior in the video-taped mother–child interaction situation varied significantly according to her educational background. With regard to the broad concept of quality of interaction behavior described above, the mother’s education accounted—even in these early phases of child development—for 4 % ( p < 0.001) of the variance within the German subgroup of participants. However, as expected we did not find substantial disparities in child characteristics in early childhood, like basic information processing abilities (habituation–dishabituation paradigm), developmental status (sensorimotor scale), or socio-emotional child characteristics coded during mother–child interaction. Interestingly, some early roots of social disparities were observed in child’s characteristics, such as sustained attention to objects and activity level in mother–child interaction. Notably, as predicted, mother–child interaction turned out to be a mutual endeavor: Interactional characteristics of the child (especially the child’s mood, her/his social interest, and continuing sustained attention to objects) and the child’s temperament (orienting/regulatory capacity) accounted for 29 % ( p < 0.001) of the differences in the overall quality of the mother’s interaction behavior, over and above the control variables (age, sex) and socio-economic conditions (equivalized family income, education of mother, living in partnership) (Weinert et al. 2016 ). Of course, it is still an open question whether the differences observed between children result from former or actual differences in the mother’s behavior or whether the differences in child characteristics and behavior are effective in eliciting their mother’s behavior. In fact, the interrelation between mother and child behavior may vary according to other factors, e.g., additional protective or risk factors (Freund et al. 2016 ). Future findings from the NEPS cohort study of newborns will contribute to explaining how social disparities (suspected at age two and beyond) emerge, how they change over time, which mechanisms contribute to their emergence, and how they impact future development and education.

Prospects and conclusions

Insights and conclusions from longitudinal studies and analyses on the conditions which influence early developmental progress, the emergence of disparities, and their impacts are relevant to educational facilities and social policy and thus to the individual child as well as to society. The present paper focused on the first waves of a large-scale German cohort study of newborns. The various measures will help to better understand the stabilities, changes, and effects of qualitative and quantitative characteristics that early learning environments and other influential conditions have. They also illustrate how the very early outcomes of infant development act as a basis for future development. The child’s development will be measured by testing the development of mathematical, language, and early natural science competencies. Domain-general cognitive abilities will also be assessed (i.e., non-verbal categorization, delay of gratification, verbal memory, and executive functions) along with indicators of socio-emotional development (subscales of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Goodman 1997 ), temperament (subscales of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ), Rothbart et al. 2001 ), and personality (BigFive; short version of the Five Factor Questionnaire for Children (FFFK); Asendorpf and van Aken 2003 ). Learning environments will be measured by interviews and questionnaires which draw on the general framework described above and will be supplemented with assessments of different facets of parenting style. To ensure standardization and reduce administration errors, all tests are carried out on tablet computers in child-oriented, playful settings.

It is worth noting that the kindergarten cohort of the NEPS, which started in 2010, also assessed comparable measures from age five onward. Here a sample of about 3000 children (institutional sample from 279 ECEC centers and 720 groups) was included. Despite differences between cohort designs (e.g., individual vs. institutional sample; child assessments at the children’s home vs. in preschool; playful test administration with vs. without tablet computers; CAPI vs. CATI interviews of the parents) the two cohort studies allow for comparisons while at the same time being characterized by partially complementary strengths and weaknesses (e.g., more elaborate information on home-learning environment vs. on institutional characteristics; extensive assessment of early roots vs. extensive assessment of further development). Among other things, this allows for an in-depth analysis of the interrelation between variations as well as an analysis of the constancies and changes in learning environments and child development, and it also relays important information concerning relevant aspects of early education and how it impacts development, educational career, and future prospects.

A better understanding of the relevant factors and conditions influencing early child development and learning together with their impact on children’s future development, educational success, and well-being is of special importance for ECEC policy. Longitudinal studies are needed because they allow analyses of the mechanism and processes of change in these decisive variables. While in cross-sectional studies causal effects cannot be inferred, longitudinal studies—especially those that enable complex group-specific growth-curve modeling and the modeling of intra-individual change—combined with experimental and quasi-experimental comparisons not only contribute significantly to gaining deeper insights into developmental and educational processes and the conditions influencing them but can also answer important questions relevant to ECEC policy such as how does early compared to late entry to institutional care impact later development in various cognitive and non-cognitive domains? Is early institutional care especially valuable (and to what extent) for different subgroups of children/families (e.g., disadvantaged families, children/families with specific risk factors, children with a migration background, refugees, multilingual children, e.g., children learning German as an (early) second or third language)? What are the determinants of the quality of home-learning environment and its effects on child development and education? What are specific risk (or protective) factors and is it possible to compensate for (or to draw on) them?

Obviously, even longitudinal studies will not deliver straightforward conclusions for ECEC policy. However, they provide an important and essential basis for evidence-based policy by informing about relevant conditions of early child education and how they impact later development (e.g., successful future development, educational drawbacks or opportunities in the social, socio-emotional, and cognitive domain). In fact, it has been suggested that high-quality early education is of special importance from a psychological, an educational, a sociological, and an economic perspective and thus is of significant relevance not only to the individual but also to society as a whole (Heckman 2013 ; Sylva et al. 2011 ). NEPS data are especially helpful when it comes to gaining a better understanding of the development of competencies and decisive conditions over the life course—the samples are carefully drawn, the validity of data is high, and longitudinal data are available in a user-friendly form for analyses and even for international comparisons.

From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS is carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg, Germany, in cooperation with a nation-wide network.

NEPS Starting Cohort Newborns, doi: 10.5157/NEPS:SC1:2.0.0 .

“Video-based Validity Analyses of Measures of Early Childhood Competencies and Home Learning Environment” (ViVA)—project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; grant to S. Weinert) within the priority program 1646.

Distress was hardly observed during mother–child interaction.

Ainsworth, M., Bell, S., & Stayton, D. (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Anders, Y., Große, C., Roßbach, H. G., Ebert, S., & Weinert, S. (2013). Preschool and primary school influences on the development of children’s early numeracy skills between the ages of 3 and 7 years in Germany. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 24 , 195–211. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2012.749791 .

Article Google Scholar

Anders, Y., Roßbach, H. G., Weinert, S., Ebert, S., Kuger, S., Lehrl, S., et al. (2012). Home and preschool learning environments and their relations to the development of early numeracy skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27 , 231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.003 .

Asendorpf, J. B., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2003). Validity of big five personality judgments in childhood. A 9 year longitudinal study. European Journal of Personality, 17 , 1–17. doi: 10.1002/per.460 .

Aßmann, C., Zinn, S., & Würbach, A. (2015). Sampling and weighting the sample of the early childhood cohort of the National Educational Panel Study (Technical Report of SUF SC1 Version 2.0.0). https://www.neps-data.de/Portals/0/NEPS/Datenzentrum/Forschungsdaten/SC1/2-0-0/SC1-2-0-0_Weighting.pdf .

Attig, M., Freund, J. D., & Weinert, S. (2015). Ein Vergleich der sensomotorischen Skala des Nationalen Bildungspanels mit den Bayley Scales bei 7 bzw. 8 Monate alten Kindern. . Presentation. 22. Tagung der Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie. Frankfurt.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2011). Differential susceptibility to rearing environment depending on dopamine-related genes: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 23 , 39–52. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000635 .

Baltes, P. B., Lindenberger, U., & Staudinger, U. M. (2006). Life span theory in developmental psychology. In W. Damon & M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 569–664). New York: Wiley.

Bäumer, T., Preis, N., Roßbach, H. -G., Stecher, L., & Klieme, E. (2011). Education processes in life-course-specific learning environments. In H. -P. Blossfeld, H. -G. Roßbach, & J. von Maurice (Eds.), Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Sonderheft. Special issue. Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (Vol. 14, pp. 87–101). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.1007/s11618-011-0183-6 .

Bayer, M., Wohlkinger, F., Freund, J. D., Ditton, H., & Weinert, S. (2015). Temperament bei Kleinkindern: Theoretischer Hintergrund, Operationalisierung im Nationalen Bildungspanel (NEPS) und empirische Befunde aus dem Forschungsprojekt VIVA (NEPS Working Paper No. 58) . Bamberg: Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsverläufe, Nationales Bildungspanel. https://www.neps-data.de/Portals/0/Working%20Papers/WP_LVIII.pdf

Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development (3rd ed.). San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment.

Bigelow, A. E., MacLean, K., Proctor, J., Myatt, T., Gillis, R., & Power, M. (2010). Maternal sensitivity throughout infancy: continuity and relation to attachment security. Infant Behavior & Development, 33 , 50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.009 .

Blossfeld, H. -P., Roßbach, H. -G., von Maurice, J. (2011). Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) [Special issue]. In Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Sonderheft, Vol. 14. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.1007/s11618-011-0198-z .

Bornstein, M., & Sigman, M. (1986). Continuity in mental development from infancy. Child Development, 57 , 251–274. doi: 10.2307/1130581 .

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 , 371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233 .

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 793–828). New York: Wiley.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. Future of Children, 7 , 55–71. doi: 10.2307/1602387 .

Brunner, M., Lang, fr, & Lüdtke, O. (2014). Erfassung der fluiden kognitiven Leistungsfähigkeit über die Lebensspanne im Rahmen der National Educational Panel Study: Expertise (NEPS Working Paper No. 42) . Bamberg: Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsverläufe, Nationales Bildungspanel.

Caspi, A., Sugden, K., Moffitt, T. E., Taylor, A., Craig, I. W., Harrington, H., et al. (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301 (5631), 386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968 .

Cattell, R. B. (1971). Abilities: their structure, growth, and action . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Dubowy, M., Ebert, S., von Maurice, J., & Weinert, S. (2008). Sprachlich-kognitive Kompetenzen beim Eintritt in den Kindergarten. Ein Vergleich von Kindern mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 40 , 124–134. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637.40.3.124 .

Ebert, S., Lockl, K., Weinert, S., Anders, Y., Kluczniok, K., & Roßbach, H. G. (2013). Internal and external influences on vocabulary development in preschool children. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 24 , 138–154. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2012.749791 .

Fagan, J. F., & Singer, L. T. (1983). Infant recognition memory as a measure of intelligence. Advances in Infancy Research, 2 , 31–78.

Fenson, L., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., Thal, D., Bates, E., Hartung, J. P., et al. (1993). Mac-Arthur communicative development inventories . San Diego: Singular Publishing Group.

Flöter, M., Egert, F., Lee, H. J., & Tietze, W. (2013). Kindliche Bildung und Entwicklung in Abhängigkeit von familiären und außerfamiliären Hintergrundfaktoren. In W. Tietze, F. Becker-Stoll, J. Bensel, A. G. Eckhardt, G. Haug-Schnabel, B. Kalicki, & H. Keller (Eds.), Nationale Untersuchung zur Bildung, Betreuung und Erziehung in der frühen Kindheit (NUBBEK) (pp. 107–137). Kiliansroda: Verlag das Netz.

Freund, J.D., Linberg, A. & Weinert, S. (Forthcoming). Grenzen der Belastbarkeit — Wann ein schwieriges Temperament die Mutter - Kleinkind - Interaktion beeinträchtigt. (working title) .

Freund, J. D., & Weinert, S. (2015). Evaluation der Erfassung frühkindlicher Temperamentsfacetten im Nationalen Bildungspanel (NEPS) über eine 9-Item Version des IBQ-R-VSF . Presentation. 22. Tagung der Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie. Frankfurt.

Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2003). Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development, 26 , 64–86.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38 , 581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x .

Goswami, U. (2008). Cognitive development—the learning brain . Hove: Psychology Press.

Halle, T., Forry, N., Hair, E., Perper, K., Wandner, L., Wessel, J., et al. (2009). Disparities in early learning and development: lessons from the early childhood longitudinal study—birth cohort (ECLS-B) . Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children . Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1999). Social world of children learning to talk . Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Heckman, J. J. (2013). Giving kids a fair chance . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hillemeier, M. M., Farkas, G., Morgan, P. L., Martin, M. A., & Maczuga, S. A. (2009). Disparities in the prevalence of cognitive delay: how early do they appear? Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 23 , 186–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.01006.x .

Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1999). Beyond modularity—a developmental perspective on cognitive science . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kavšek, M. (2004). Predicting later IQ from infant visual habituation and dishabituation: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25 , 369–393. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2004.04.006 .

Kreyenfeld, M., & Krapf, S. (2016). Soziale Ungleichheit und Kinderbetreuung—Eine Analyse der sozialen und ökonomischen Determinanten der Nutzung von Kindertageseinrichtungen. In R. Becker & W. Lauterbach (Eds.), Bildung als Privileg (pp. 119–144). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Law, J., King, T., & Rush, R. (2014). Newcastle University evidence paper for the read on, get on coalition: An analysis of early years and primary school age language and literacy data from the millennium cohort study . London: Save the Children.

Linberg, T., Bäumer, T., & Roßbach, H. G. (2013). Data on early child education and care learning environments in Germany. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 7 , 24–42. doi: 10.1007/2288-6729-7-1-24 .

Linberg, A., Freund, J.D., Mann, D. Bedingungen sensitiver Mutter-Kind-Interaktionen. In H. Wadepohl, K. Mackowiak, K. Fröhlich-Gildhoff, D. Weltzien (Eds.), Interaktionsgestaltung in Familie und Kindertagesbetreuung. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag. (in press) .

Lloyd, C. A., & Masur, E. F. (2014). Infant behaviors influence mothers’ provision of responsive and directive behaviors. Infant Behavior & Development, 37 , 276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.04.004 .

Mayberry, R., Lock, E., & Kazmi, H. (2002). Linguistic ability and early language exposure. Nature, 417 , 38. doi: 10.1038/417038a

Mayer, S. (2013). Kindliches Temperament im ersten Lebensjahr und mütterliche Sensitivität. Masterarbeit . Winterthur: Züricher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften.

McCall, R. B., Eichorn, D. H., Hogarty, P. S., Uzgiris, I. C., & Schaefer, E. S. (1977). Transitions in early mental development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 42 , 1–108. doi: 10.2307/1165992 .

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Fradley, E., & Tuckey, M. (2001). Rethinking maternal sensitivity: mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42 , 637–648. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00759 .

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1998). Relations between family predictors and child outcomes: are they weaker for children in child care? Developmental Psychology, 34 , 1119–1128.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2005). Child care and child development. Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development . New York: Guilford.

Noble, K. G., McCandliss, B. D., & Farah, M. J. (2007). Socioeconomic gradients predict individual differences in neurocognitive abilities. Developmental Science, 10 , 464–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00600.x .

Nozadi, S. S., Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Bolnick, R., Eggum-Wilkens, N. D., Smith, C. L., et al. (2013). Prediction of toddlers’ expressive language from maternal sensitivity and toddlers’ anger expressions: a developmental perspective. Infant Behavior & Development, 36 , 650–661. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.002 .

Pahnke, J. (2007). Visuelle Habituation und Dishabituation als Maße kognitiver Fähigkeiten im Säuglingsalter . Dissertation. Heidelberg: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg.

Pearson, R. M., Heron, J., Melotti, R., Joinson, C., Stein, A., Ramchandani, P. G., et al. (2011). The association between observed non-verbal maternal responses at 12 months and later infant development at 18 months and IQ at 4 years: a longitudinal study. Infant Behavior & Development, 34 , 525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.003 .

Piaget, J. (1970). Piaget’s theory. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Carmichael’s manual of child psychology (Vol. I, pp. 703–732). New York: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., Hershey, K. L., & Fisher, P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development, 72 , 1394–1408.

Schlesiger, C., Lorenz, J., Weinert, S., Schneider, T., & Roßbach, H. G. (2011). From birth to early child care. In H. P. Blossfeld, H. G. Roßbach, & J. von Maurice (Eds.), Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Special issue. Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (Vol. 14, pp. 187–202). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.1007/s11618-011-0186-3 .

Sokolov, Y. N. (1990). The orienting response, and future directions of its development. Pavlovian Journal of Biological Science, 25 , 142–150.

Sommer, A., Hachul, C., & Roßbach, H. G. (2016). Video-based assessment and rating of parent-child-interaction within the National Educational Panel Study. In H. P. Blossfeld, J. von Maurice, M. Bayer, & J. Skopek (Eds.), Methodological issues of longitudinal surveys. The example of the National Educational Panel Study (Vol. 14, pp. 151–167). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Sommer, A., & Mann, D. (2015). Qualität elterlichen Interaktionsverhaltens: Erfassung von Interaktionen mithilfe der Eltern-Kind-Interaktions-Einschätzskala im Nationalen Bildungspanel (NEPS Working Paper No. 56). Bamberg: Leibniz-Institute für Bildungsverläufe, Nationales Bildungspanel. https://www.neps-data.de/Portals/0/Working%20Papers/WP_LVI.pdf .

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2016). Kindertagesbetreuung regional 2015 . Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2011). Preschool quality and educational outcomes at age 11: low quality has little benefit. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 9 , 109–124.

Sylva, K., Siraj-Blatchford, I., Taggart, B., Sammons, P., Melhuish, E. C., Elliot, K., et al. (2006). Capturing quality in early childhood through environmental rating scales. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21 , 76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.01.003 .

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Bornstein, M. H., & Baumwell, L. (2001). Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development, 72 , 748–767.

van den Bloom, D. C., & Hoeksma, J. B. (1994). The effect of infant irritability on mother-infant interaction: a growth-curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 30 , 581–590.

Vogel, F., Freund, J. D., & Weinert, S. (2015). Vergleichbarkeit von Interaktionsmaßen über verschiedene Situationen bei Säuglingen: Ergebnisse des Projekts ViVA . Poster. 22. Tagung der Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie. Frankfurt.

Waldfogel, J. (2001). International policies toward parental leave and child care. Future Child, 11 , 98–111.

Weinert, S., Artelt, C., Prenzel, M., Senkbeil, M., Ehmke, T., & Carstensen, C. H. (2011). Development of competencies across the life span. In H. P. Blossfeld, H. G. Roßbach, & J. von Maurice (Eds.), Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: Special issue. Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) (Vol. 14, pp. 67–86). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi: 10.1007/s11618-011-0182-7 .

Weinert, S., Attig, M. & Roßbach, H.G. (2016). The emergence of social disparities—evidence on early mother–child interaction and infant development from the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). In H.P. Blossfeld, N. Kulic, J. Skopek, & M. Triventi (Eds.), Childcare, early education, and social inequality — an international perspective . Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. (in press) .

Weinert, S., & Ebert, S. (2013). Spracherwerb im Vorschulalter: soziale Disparitäten und Einflussvariablen auf den Grammatikerwerb. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 16 , 303–332. doi: 10.1007/s11618-013-0354-8 .

Weinert, S., Ebert, S., & Dubowy, M. (2010). Kompetenzen und soziale Disparitäten im Vorschulalter. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 1 , 32–45.

Weinert, S., Ebert, S., Lockl, K., & Kuger, S. (2012). Disparitäten im Wortschatzerwerb: Zum Einfluss des Arbeitsgedächtnisses und der Anregungsqualität in Kindergarten und Familie auf den Erwerb lexikalischen Wissens. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 40 , 4–25.

Wood, D. (1989). Social interaction as tutoring. In M. H. Bornstein & J. S. Bruner (Eds.), Crosscurrents in contemporary psychology. Interaction in human development (pp. 59–80). Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Download references

Authors’ contributions

SW conceptualized and drafted the overall manuscript, sequence alignment, and revisions. In addition she cooperatively conceived the design and assessments of the studies, in particular the assessment of early child competencies, and the analyses of social disparities. AL especially drafted the part on the learning environments and the assessment of mother-child interaction; she conducted the data analyses on mother-child interaction and supported the analyses on ecologic validity of mother-child-interaction. MA contributed to the description of the overall design and did the analyses on early roots of social disparities. She is also involved in the conceptualization and coordination of data assessment of the infant cohort study. TL drafted the part on regulations in Germany and contributed to the description of the assessment of learning environments. He is also involved in the conceptualization of the assessment of this data. JDF did the analyses on the reliability and validity of measures of early child characteristics; he drafted this part and cooperatively planned and conducted the validation study. All authors were involved in the sequence alignment and revisions, and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Developmental Psychology, University of Bamberg, 96045, Bamberg, Germany

Sabine Weinert & Jan-David Freund

Department of Early Childhood Education, University of Bamberg, 96045, Bamberg, Germany

Anja Linberg

Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories, Wilhelmsplatz 3, 96047, Bamberg, Germany

Manja Attig & Tobias Linberg

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sabine Weinert .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Weinert, S., Linberg, A., Attig, M. et al. Analyzing early child development, influential conditions, and future impacts: prospects of a German newborn cohort study. ICEP 10 , 7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-016-0022-6

Download citation

Received : 11 April 2016

Accepted : 27 September 2016

Published : 07 October 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-016-0022-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Birth cohort

- Longitudinal study

- Early child capacities and development

- Learning environment

- Social disparities

Advertisement

Theories of Child Development and Their Impact on Early Childhood Education and Care

- Published: 29 October 2021

- Volume 51 , pages 15–30, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Olivia N. Saracho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4108-7790 1

140k Accesses

16 Citations

Explore all metrics

Developmental theorists use their research to generate philosophies on children’s development. They organize and interpret data based on a scheme to develop their theory. A theory refers to a systematic statement of principles related to observed phenomena and their relationship to each other. A theory of child development looks at the children's growth and behavior and interprets it. It suggests elements in the child's genetic makeup and the environmental conditions that influence development and behavior and how these elements are related. Many developmental theories offer insights about how the performance of individuals is stimulated, sustained, directed, and encouraged. Psychologists have established several developmental theories. Many different competing theories exist, some dealing with only limited domains of development, and are continuously revised. This article describes the developmental theories and their founders who have had the greatest influence on the fields of child development, early childhood education, and care. The following sections discuss some influences on the individuals’ development, such as theories, theorists, theoretical conceptions, and specific principles. It focuses on five theories that have had the most impact: maturationist, constructivist, behavioral, psychoanalytic, and ecological. Each theory offers interpretations on the meaning of children's development and behavior. Although the theories are clustered collectively into schools of thought, they differ within each school.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

The author is grateful to Mary Jalongo for her expert editing and her keen eye for the smallest details.

Although Watson was the first to maintain explicitly that psychology was a natural science, behaviorism in both theory and practice had originated much earlier than 1913. Watson offered a vital incentive to behaviorism, but several others had started the process. He never stated to have created “behavioral psychology.” Some behaviorists consider him a model of the approach rather than an originator of behaviorism (Malone, 2014 ). Still, his presence has significantly influenced the status of present psychology and its development.

Alschuler, R., & Hattwick, L. (1947). Painting and personality . University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Axline, V. (1974). Play therapy . Ballentine Books.

Berk, L. (2021). Infants, children, and adolescents . Pearson.

Bijou, S. W. (1975). Development in the preschool years: A functional analysis. American Psychologist, 30 (8), 829–837. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077069

Article Google Scholar

Bijou, S. W. (1977). Behavior analysis applied to early childhood education. In B. Spodek & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Early childhood education: Issues and insights (pp. 138–156). McCutchan Publishing Corporation.

Boghossion, P. (2006). Behaviorism, constructivism, and Socratic pedagogy. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38 (6), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2006.00226.x

Bower, B. (1986). Skinner boxing. Science News, 129 (6), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/3970364

Briner, M. (1999). Learning theories . University of Colorado.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45 (1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127743

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning . Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (2004). A short history of psychological theories of learning. Daedalus, 133 (1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1162/001152604772746657

Coles, R., Hunt, R., & Maher, B. (2002). Erik Erikson: Faculty of Arts and Sciences Memorial Minute. Harvard Gazette Archives . http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/03.07/22-memorialminute.html

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020). Erik Erikson . https://www.britannica.com/biography/Erik-Erikson

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society . Norton.

Freud, A. (1935). Psychoanalysis for teachers and parents . Emerson Books.

Friedman, L. J. (1999). Identity’s architect: A biography of Erik H . Scribner Publishing Company.

Gesell, A. (1928). In infancy and human growth . Macmillan Co.

Book Google Scholar

Gesell, A. (1933). Maturation and the patterning of behavior. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A handbook of child psychology (pp. 209–235). Russell & Russell/Atheneum Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1037/11552-004

Chapter Google Scholar

Gesell, A., & Ilg, F. L. (1946). The child from five to ten . Harper & Row.

Gesell, A., Ilg, F. L., & Ames, L. B. (1978). Child behavior . Harper & Row.

Gesell, A., & Thompson, H. (1938). The psychology of early growth, including norms of infant behavior and a method of genetic analysis . Macmillan Co.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1995). Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning . Falmer.

von Glasersfeld, E. (2005). Introduction: Aspects of constructivism. In C. T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism: Theory, perspectives and practice (pp. 3–7). Teachers College.

Graham, S., & Weiner, B. (1996). Theories and principles of motivation. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 63–84). Macmillan Library Reference.

Gray, P. O., & Bjorklund, D. F. (2017). Psychology (8th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Hilgard, E. R. (1987). Psychology in America: A historical survey . Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Hunt, J. . Mc. V. (1961). Intelligence and experience . Ronald Press.

Jenkins, E. W. (2000). Constructivism in school science education: Powerful model or the most dangerous intellectual tendency? Science and Education, 9 , 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008778120803

Jones, M. G., & Brader-Araje, L. (2002). The impact of constructivism on education: Language, discourse, and meaning. American Communication Studies, 5 (3), 1–1.

Kamii, C., & DeVries, R. (1978/1993.) Physical knowledge in preschool education: Implications of Piaget’s theory . Teachers College Press.

King, P. H. (1983). The life and work of Melanie Klein in the British Psycho-Analytical Society. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 64 (Pt 3), 251–260. PMID: 6352537.

Malone, J. C. (2014). Did John B. Watson really “Found” Behaviorism? The Behavior Analyst , 37 (1) , 1–12. https://doi-org.proxy-um.researchport.umd.edu/10.1007/s40614-014-0004-3

Miller, P. H. (2016). Theories of developmental psychology (6th ed.). Worth Publishers.

Morphett, M. V., & Washburne, C. (1931). When should children begin to read? Elementary School Journal, 31 (7), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1086/456609

Murphy, L. (1962). The widening world of childhood . Basic Books.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (No date). Build your public policy knowledge/Head Start . https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/head-start

Reichling, L. (2017). The Skinner Box. Article Library. https://blog.customboxesnow.com/the-skinner-box/

Peters, E. M. (2015). Child developmental theories: A contrast overview. Retrieved from https://learningsupportservicesinc.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/child-developmental-theories-a-contrast-overview/

Piaget, J. (1963). The origins of intelligence in children . Norton.

Piaget, J. (1967/1971). Biology and knowledge: An essay on the relations between organic regulations and cognitive processes . Trans. B. Walsh. University of Chicago Press.

Safran, J. D., & Gardner-Schuster, E. (2016). Psychoanalysis. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mental health (2nd ed., pp. 339–347). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00189-0

Saracho, O. N. (2017). Literacy and language: New developments in research, theory, and practice. Early Child Development and Care, 187 (3–4), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1282235

Saracho, O. N. (2019). Motivation theories, theorists, and theoretical conceptions. In O. N. Saracho (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on research in motivation in early childhood education (pp. 19–42). Information Age Publishing.

Saracho, O. N. (2020). An integrated play-based curriculum for young children. Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group . https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429440991

Saracho, O. N., & Evans, R. (2021). Theorists and their developmental theories. Early Child Development and Care, 191 (7–8), 993–1001.

Scarr, S. (1992). Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Development, 63 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130897

Schunk, D. (2021). Learning theories: An educational perspective (8th ed.). Pearson.

Shabani, K., Khatib, M., & Ebadi, S. (2010). Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development: Instructional implications and teachers’ professional development. English Language Teaching, 3 (4), 237–248.

Skinner, B. F. (1914). About behaviorism . Jonathan Cape Publishers.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis . D. Appleton-Century Co.

Skinner, B. F. (1953/2005). Science and human behavior . Macmillan. Later published by the B. F. Foundation in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Spodek, B., & Saracho, O. N. (1994). Right from the start: Teaching children ages three to eight . Allyn & Bacon.

Steiner, J. (2017). Lectures on technique by Melanie Klein: Edited with critical review by John Steiner (1st ed.). Routledge.

Strickland, C. E., & Burgess, C. (1965). Health, growth and heredity: G. Stanley Hall on natural education . Teachers College Press.

Thorndike, E. L. (1906). The principles of teaching . A. G. Seiler.

Torre, D. M., Daley, B. J., Sebastian, J. L., & Elnicki, D. M. (2006). Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. The American Journal of Medicine, 119 (10), 903–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.037

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/1962). Thought and language . The MIT Press. (Original work published in 1934).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1971). Psychology of art . The MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20 (2), 158–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074428

Weber, E. (1984). Ideas influencing early childhood education: A theoretical analysis . Teachers College Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Maryland, College Park, USA

Olivia N. Saracho

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Olivia N. Saracho .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Saracho, O.N. Theories of Child Development and Their Impact on Early Childhood Education and Care. Early Childhood Educ J 51 , 15–30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01271-5

Download citation

Accepted : 22 September 2021

Published : 29 October 2021

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01271-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Child development

- Early childhood education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government