Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Editorial Manager, our manuscript submissions site will be unavailable between 12pm April 5, 2024 and 12pm April 8 2024 (Pacific Standard Time). We apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

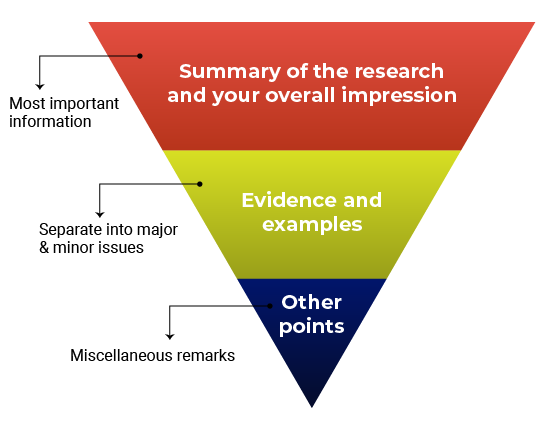

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER COLUMN

- 08 October 2018

How to write a thorough peer review

- Mathew Stiller-Reeve 0

Mathew Stiller-Reeve is a climate researcher at NORCE/Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research in Bergen, Norway, the leader of SciSnack.com, and a thematic editor at Geoscience Communication .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Scientists do not receive enough peer-review training. To improve this situation, a small group of editors and I developed a peer-review workflow to guide reviewers in delivering useful and thorough analyses that can really help authors to improve their papers.

Access options

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06991-0

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged. You can get in touch with the editor at [email protected].

Related Articles

Engage more early-career scientists as peer reviewers

Help graduate students to become good peer reviewers

- Peer review

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Career Column 08 APR 24

Is AI ready to mass-produce lay summaries of research articles?

Nature Index 20 MAR 24

Peer-replication model aims to address science’s ‘reproducibility crisis’

Nature Index 13 MAR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

Ready or not, AI is coming to science education — and students have opinions

Career Feature 08 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Postdoctoral Associate- Endometriosis

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics

Located in the beautiful coastal city of Dalian, surrounded by mountains and sea, DICP seeks all talents from around the globe.

Dalian, Liaoning, China

The Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP)

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Qualifications: PhD degree in chemistry, radiochemistry, or nuclear medicine technology with at least 3 years of PET radiochemistry work experience i

Charlottesville, Virginia

University of Virginia Health

Postdoctoral Associate

Palm Beach, Florida

University of Florida, Scripps Institute

Laboratory Director

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to write a good scientific review article

Affiliation.

- 1 The FEBS Journal Editorial Office, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 35792782

- DOI: 10.1111/febs.16565

Literature reviews are valuable resources for the scientific community. With research accelerating at an unprecedented speed in recent years and more and more original papers being published, review articles have become increasingly important as a means to keep up to date with developments in a particular area of research. A good review article provides readers with an in-depth understanding of a field and highlights key gaps and challenges to address with future research. Writing a review article also helps to expand the writer's knowledge of their specialist area and to develop their analytical and communication skills, amongst other benefits. Thus, the importance of building review-writing into a scientific career cannot be overstated. In this instalment of The FEBS Journal's Words of Advice series, I provide detailed guidance on planning and writing an informative and engaging literature review.

© 2022 Federation of European Biochemical Societies.

Publication types

- Review Literature as Topic*

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

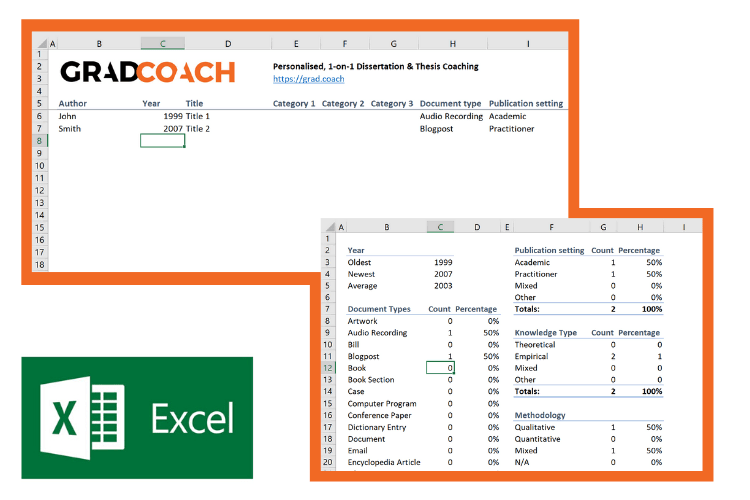

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Page Content

Overview of the review report format, the first read-through, first read considerations, spotting potential major flaws, concluding the first reading, rejection after the first reading, before starting the second read-through, doing the second read-through, the second read-through: section by section guidance, how to structure your report, on presentation and style, criticisms & confidential comments to editors, the recommendation, when recommending rejection, additional resources, step by step guide to reviewing a manuscript.

When you receive an invitation to peer review, you should be sent a copy of the paper's abstract to help you decide whether you wish to do the review. Try to respond to invitations promptly - it will prevent delays. It is also important at this stage to declare any potential Conflict of Interest.

The structure of the review report varies between journals. Some follow an informal structure, while others have a more formal approach.

" Number your comments!!! " (Jonathon Halbesleben, former Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Informal Structure

Many journals don't provide criteria for reviews beyond asking for your 'analysis of merits'. In this case, you may wish to familiarize yourself with examples of other reviews done for the journal, which the editor should be able to provide or, as you gain experience, rely on your own evolving style.

Formal Structure

Other journals require a more formal approach. Sometimes they will ask you to address specific questions in your review via a questionnaire. Or they might want you to rate the manuscript on various attributes using a scorecard. Often you can't see these until you log in to submit your review. So when you agree to the work, it's worth checking for any journal-specific guidelines and requirements. If there are formal guidelines, let them direct the structure of your review.

In Both Cases

Whether specifically required by the reporting format or not, you should expect to compile comments to authors and possibly confidential ones to editors only.

Following the invitation to review, when you'll have received the article abstract, you should already understand the aims, key data and conclusions of the manuscript. If you don't, make a note now that you need to feedback on how to improve those sections.

The first read-through is a skim-read. It will help you form an initial impression of the paper and get a sense of whether your eventual recommendation will be to accept or reject the paper.

Keep a pen and paper handy when skim-reading.

Try to bear in mind the following questions - they'll help you form your overall impression:

- What is the main question addressed by the research? Is it relevant and interesting?

- How original is the topic? What does it add to the subject area compared with other published material?

- Is the paper well written? Is the text clear and easy to read?

- Are the conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented? Do they address the main question posed?

- If the author is disagreeing significantly with the current academic consensus, do they have a substantial case? If not, what would be required to make their case credible?

- If the paper includes tables or figures, what do they add to the paper? Do they aid understanding or are they superfluous?

While you should read the whole paper, making the right choice of what to read first can save time by flagging major problems early on.

Editors say, " Specific recommendations for remedying flaws are VERY welcome ."

Examples of possibly major flaws include:

- Drawing a conclusion that is contradicted by the author's own statistical or qualitative evidence

- The use of a discredited method

- Ignoring a process that is known to have a strong influence on the area under study

If experimental design features prominently in the paper, first check that the methodology is sound - if not, this is likely to be a major flaw.

You might examine:

- The sampling in analytical papers

- The sufficient use of control experiments

- The precision of process data

- The regularity of sampling in time-dependent studies

- The validity of questions, the use of a detailed methodology and the data analysis being done systematically (in qualitative research)

- That qualitative research extends beyond the author's opinions, with sufficient descriptive elements and appropriate quotes from interviews or focus groups

Major Flaws in Information

If methodology is less of an issue, it's often a good idea to look at the data tables, figures or images first. Especially in science research, it's all about the information gathered. If there are critical flaws in this, it's very likely the manuscript will need to be rejected. Such issues include:

- Insufficient data

- Unclear data tables

- Contradictory data that either are not self-consistent or disagree with the conclusions

- Confirmatory data that adds little, if anything, to current understanding - unless strong arguments for such repetition are made

If you find a major problem, note your reasoning and clear supporting evidence (including citations).

After the initial read and using your notes, including those of any major flaws you found, draft the first two paragraphs of your review - the first summarizing the research question addressed and the second the contribution of the work. If the journal has a prescribed reporting format, this draft will still help you compose your thoughts.

The First Paragraph

This should state the main question addressed by the research and summarize the goals, approaches, and conclusions of the paper. It should:

- Help the editor properly contextualize the research and add weight to your judgement

- Show the author what key messages are conveyed to the reader, so they can be sure they are achieving what they set out to do

- Focus on successful aspects of the paper so the author gets a sense of what they've done well

The Second Paragraph

This should provide a conceptual overview of the contribution of the research. So consider:

- Is the paper's premise interesting and important?

- Are the methods used appropriate?

- Do the data support the conclusions?

After drafting these two paragraphs, you should be in a position to decide whether this manuscript is seriously flawed and should be rejected (see the next section). Or whether it is publishable in principle and merits a detailed, careful read through.

Even if you are coming to the opinion that an article has serious flaws, make sure you read the whole paper. This is very important because you may find some really positive aspects that can be communicated to the author. This could help them with future submissions.

A full read-through will also make sure that any initial concerns are indeed correct and fair. After all, you need the context of the whole paper before deciding to reject. If you still intend to recommend rejection, see the section "When recommending rejection."

Once the paper has passed your first read and you've decided the article is publishable in principle, one purpose of the second, detailed read-through is to help prepare the manuscript for publication. You may still decide to recommend rejection following a second reading.

" Offer clear suggestions for how the authors can address the concerns raised. In other words, if you're going to raise a problem, provide a solution ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Preparation

To save time and simplify the review:

- Don't rely solely upon inserting comments on the manuscript document - make separate notes

- Try to group similar concerns or praise together

- If using a review program to note directly onto the manuscript, still try grouping the concerns and praise in separate notes - it helps later

- Note line numbers of text upon which your notes are based - this helps you find items again and also aids those reading your review

Now that you have completed your preparations, you're ready to spend an hour or so reading carefully through the manuscript.

As you're reading through the manuscript for a second time, you'll need to keep in mind the argument's construction, the clarity of the language and content.

With regard to the argument’s construction, you should identify:

- Any places where the meaning is unclear or ambiguous

- Any factual errors

- Any invalid arguments

You may also wish to consider:

- Does the title properly reflect the subject of the paper?

- Does the abstract provide an accessible summary of the paper?

- Do the keywords accurately reflect the content?

- Is the paper an appropriate length?

- Are the key messages short, accurate and clear?

Not every submission is well written. Part of your role is to make sure that the text’s meaning is clear.

Editors say, " If a manuscript has many English language and editing issues, please do not try and fix it. If it is too bad, note that in your review and it should be up to the authors to have the manuscript edited ."

If the article is difficult to understand, you should have rejected it already. However, if the language is poor but you understand the core message, see if you can suggest improvements to fix the problem:

- Are there certain aspects that could be communicated better, such as parts of the discussion?

- Should the authors consider resubmitting to the same journal after language improvements?

- Would you consider looking at the paper again once these issues are dealt with?

On Grammar and Punctuation

Your primary role is judging the research content. Don't spend time polishing grammar or spelling. Editors will make sure that the text is at a high standard before publication. However, if you spot grammatical errors that affect clarity of meaning, then it's important to highlight these. Expect to suggest such amendments - it's rare for a manuscript to pass review with no corrections.

A 2010 study of nursing journals found that 79% of recommendations by reviewers were influenced by grammar and writing style (Shattel, et al., 2010).

1. The Introduction

A well-written introduction:

- Sets out the argument

- Summarizes recent research related to the topic

- Highlights gaps in current understanding or conflicts in current knowledge

- Establishes the originality of the research aims by demonstrating the need for investigations in the topic area

- Gives a clear idea of the target readership, why the research was carried out and the novelty and topicality of the manuscript

Originality and Topicality

Originality and topicality can only be established in the light of recent authoritative research. For example, it's impossible to argue that there is a conflict in current understanding by referencing articles that are 10 years old.

Authors may make the case that a topic hasn't been investigated in several years and that new research is required. This point is only valid if researchers can point to recent developments in data gathering techniques or to research in indirectly related fields that suggest the topic needs revisiting. Clearly, authors can only do this by referencing recent literature. Obviously, where older research is seminal or where aspects of the methodology rely upon it, then it is perfectly appropriate for authors to cite some older papers.

Editors say, "Is the report providing new information; is it novel or just confirmatory of well-known outcomes ?"

It's common for the introduction to end by stating the research aims. By this point you should already have a good impression of them - if the explicit aims come as a surprise, then the introduction needs improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

Academic research should be replicable, repeatable and robust - and follow best practice.

Replicable Research

This makes sufficient use of:

- Control experiments

- Repeated analyses

- Repeated experiments

These are used to make sure observed trends are not due to chance and that the same experiment could be repeated by other researchers - and result in the same outcome. Statistical analyses will not be sound if methods are not replicable. Where research is not replicable, the paper should be recommended for rejection.

Repeatable Methods

These give enough detail so that other researchers are able to carry out the same research. For example, equipment used or sampling methods should all be described in detail so that others could follow the same steps. Where methods are not detailed enough, it's usual to ask for the methods section to be revised.

Robust Research

This has enough data points to make sure the data are reliable. If there are insufficient data, it might be appropriate to recommend revision. You should also consider whether there is any in-built bias not nullified by the control experiments.

Best Practice

During these checks you should keep in mind best practice:

- Standard guidelines were followed (e.g. the CONSORT Statement for reporting randomized trials)

- The health and safety of all participants in the study was not compromised

- Ethical standards were maintained

If the research fails to reach relevant best practice standards, it's usual to recommend rejection. What's more, you don't then need to read any further.

3. Results and Discussion

This section should tell a coherent story - What happened? What was discovered or confirmed?

Certain patterns of good reporting need to be followed by the author:

- They should start by describing in simple terms what the data show

- They should make reference to statistical analyses, such as significance or goodness of fit

- Once described, they should evaluate the trends observed and explain the significance of the results to wider understanding. This can only be done by referencing published research

- The outcome should be a critical analysis of the data collected

Discussion should always, at some point, gather all the information together into a single whole. Authors should describe and discuss the overall story formed. If there are gaps or inconsistencies in the story, they should address these and suggest ways future research might confirm the findings or take the research forward.

4. Conclusions

This section is usually no more than a few paragraphs and may be presented as part of the results and discussion, or in a separate section. The conclusions should reflect upon the aims - whether they were achieved or not - and, just like the aims, should not be surprising. If the conclusions are not evidence-based, it's appropriate to ask for them to be re-written.

5. Information Gathered: Images, Graphs and Data Tables

If you find yourself looking at a piece of information from which you cannot discern a story, then you should ask for improvements in presentation. This could be an issue with titles, labels, statistical notation or image quality.

Where information is clear, you should check that:

- The results seem plausible, in case there is an error in data gathering

- The trends you can see support the paper's discussion and conclusions

- There are sufficient data. For example, in studies carried out over time are there sufficient data points to support the trends described by the author?

You should also check whether images have been edited or manipulated to emphasize the story they tell. This may be appropriate but only if authors report on how the image has been edited (e.g. by highlighting certain parts of an image). Where you feel that an image has been edited or manipulated without explanation, you should highlight this in a confidential comment to the editor in your report.

6. List of References

You will need to check referencing for accuracy, adequacy and balance.

Where a cited article is central to the author's argument, you should check the accuracy and format of the reference - and bear in mind different subject areas may use citations differently. Otherwise, it's the editor’s role to exhaustively check the reference section for accuracy and format.

You should consider if the referencing is adequate:

- Are important parts of the argument poorly supported?

- Are there published studies that show similar or dissimilar trends that should be discussed?

- If a manuscript only uses half the citations typical in its field, this may be an indicator that referencing should be improved - but don't be guided solely by quantity

- References should be relevant, recent and readily retrievable

Check for a well-balanced list of references that is:

- Helpful to the reader

- Fair to competing authors

- Not over-reliant on self-citation

- Gives due recognition to the initial discoveries and related work that led to the work under assessment

You should be able to evaluate whether the article meets the criteria for balanced referencing without looking up every reference.

7. Plagiarism

By now you will have a deep understanding of the paper's content - and you may have some concerns about plagiarism.

Identified Concern

If you find - or already knew of - a very similar paper, this may be because the author overlooked it in their own literature search. Or it may be because it is very recent or published in a journal slightly outside their usual field.

You may feel you can advise the author how to emphasize the novel aspects of their own study, so as to better differentiate it from similar research. If so, you may ask the author to discuss their aims and results, or modify their conclusions, in light of the similar article. Of course, the research similarities may be so great that they render the work unoriginal and you have no choice but to recommend rejection.

"It's very helpful when a reviewer can point out recent similar publications on the same topic by other groups, or that the authors have already published some data elsewhere ." (Editor feedback)

Suspected Concern

If you suspect plagiarism, including self-plagiarism, but cannot recall or locate exactly what is being plagiarized, notify the editor of your suspicion and ask for guidance.

Most editors have access to software that can check for plagiarism.

Editors are not out to police every paper, but when plagiarism is discovered during peer review it can be properly addressed ahead of publication. If plagiarism is discovered only after publication, the consequences are worse for both authors and readers, because a retraction may be necessary.

For detailed guidelines see COPE's Ethical guidelines for reviewers and Wiley's Best Practice Guidelines on Publishing Ethics .

8. Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

After the detailed read-through, you will be in a position to advise whether the title, abstract and key words are optimized for search purposes. In order to be effective, good SEO terms will reflect the aims of the research.

A clear title and abstract will improve the paper's search engine rankings and will influence whether the user finds and then decides to navigate to the main article. The title should contain the relevant SEO terms early on. This has a major effect on the impact of a paper, since it helps it appear in search results. A poor abstract can then lose the reader's interest and undo the benefit of an effective title - whilst the paper's abstract may appear in search results, the potential reader may go no further.

So ask yourself, while the abstract may have seemed adequate during earlier checks, does it:

- Do justice to the manuscript in this context?

- Highlight important findings sufficiently?

- Present the most interesting data?

Editors say, " Does the Abstract highlight the important findings of the study ?"

If there is a formal report format, remember to follow it. This will often comprise a range of questions followed by comment sections. Try to answer all the questions. They are there because the editor felt that they are important. If you're following an informal report format you could structure your report in three sections: summary, major issues, minor issues.

- Give positive feedback first. Authors are more likely to read your review if you do so. But don't overdo it if you will be recommending rejection

- Briefly summarize what the paper is about and what the findings are

- Try to put the findings of the paper into the context of the existing literature and current knowledge

- Indicate the significance of the work and if it is novel or mainly confirmatory

- Indicate the work's strengths, its quality and completeness

- State any major flaws or weaknesses and note any special considerations. For example, if previously held theories are being overlooked

Major Issues

- Are there any major flaws? State what they are and what the severity of their impact is on the paper

- Has similar work already been published without the authors acknowledging this?

- Are the authors presenting findings that challenge current thinking? Is the evidence they present strong enough to prove their case? Have they cited all the relevant work that would contradict their thinking and addressed it appropriately?

- If major revisions are required, try to indicate clearly what they are

- Are there any major presentational problems? Are figures & tables, language and manuscript structure all clear enough for you to accurately assess the work?

- Are there any ethical issues? If you are unsure it may be better to disclose these in the confidential comments section

Minor Issues

- Are there places where meaning is ambiguous? How can this be corrected?

- Are the correct references cited? If not, which should be cited instead/also? Are citations excessive, limited, or biased?

- Are there any factual, numerical or unit errors? If so, what are they?

- Are all tables and figures appropriate, sufficient, and correctly labelled? If not, say which are not

Your review should ultimately help the author improve their article. So be polite, honest and clear. You should also try to be objective and constructive, not subjective and destructive.

You should also:

- Write clearly and so you can be understood by people whose first language is not English

- Avoid complex or unusual words, especially ones that would even confuse native speakers

- Number your points and refer to page and line numbers in the manuscript when making specific comments

- If you have been asked to only comment on specific parts or aspects of the manuscript, you should indicate clearly which these are

- Treat the author's work the way you would like your own to be treated

Most journals give reviewers the option to provide some confidential comments to editors. Often this is where editors will want reviewers to state their recommendation - see the next section - but otherwise this area is best reserved for communicating malpractice such as suspected plagiarism, fraud, unattributed work, unethical procedures, duplicate publication, bias or other conflicts of interest.

However, this doesn't give reviewers permission to 'backstab' the author. Authors can't see this feedback and are unable to give their side of the story unless the editor asks them to. So in the spirit of fairness, write comments to editors as though authors might read them too.

Reviewers should check the preferences of individual journals as to where they want review decisions to be stated. In particular, bear in mind that some journals will not want the recommendation included in any comments to authors, as this can cause editors difficulty later - see Section 11 for more advice about working with editors.

You will normally be asked to indicate your recommendation (e.g. accept, reject, revise and resubmit, etc.) from a fixed-choice list and then to enter your comments into a separate text box.

Recommending Acceptance

If you're recommending acceptance, give details outlining why, and if there are any areas that could be improved. Don't just give a short, cursory remark such as 'great, accept'. See Improving the Manuscript

Recommending Revision

Where improvements are needed, a recommendation for major or minor revision is typical. You may also choose to state whether you opt in or out of the post-revision review too. If recommending revision, state specific changes you feel need to be made. The author can then reply to each point in turn.

Some journals offer the option to recommend rejection with the possibility of resubmission – this is most relevant where substantial, major revision is necessary.

What can reviewers do to help? " Be clear in their comments to the author (or editor) which points are absolutely critical if the paper is given an opportunity for revisio n." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Recommending Rejection

If recommending rejection or major revision, state this clearly in your review (and see the next section, 'When recommending rejection').

Where manuscripts have serious flaws you should not spend any time polishing the review you've drafted or give detailed advice on presentation.

Editors say, " If a reviewer suggests a rejection, but her/his comments are not detailed or helpful, it does not help the editor in making a decision ."

In your recommendations for the author, you should:

- Give constructive feedback describing ways that they could improve the research

- Keep the focus on the research and not the author. This is an extremely important part of your job as a reviewer

- Avoid making critical confidential comments to the editor while being polite and encouraging to the author - the latter may not understand why their manuscript has been rejected. Also, they won't get feedback on how to improve their research and it could trigger an appeal

Remember to give constructive criticism even if recommending rejection. This helps developing researchers improve their work and explains to the editor why you felt the manuscript should not be published.

" When the comments seem really positive, but the recommendation is rejection…it puts the editor in a tough position of having to reject a paper when the comments make it sound like a great paper ." (Jonathon Halbesleben, Editor of Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology)

Visit our Wiley Author Learning and Training Channel for expert advice on peer review.

Watch the video, Ethical considerations of Peer Review

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?