ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, what is differentiated instruction examples of how to differentiate instruction in the classroom.

Just as everyone has a unique fingerprint, every student has an individual learning style. Chances are, not all of your students grasp a subject in the same way or share the same level of ability. So how can you better deliver your lessons to reach everyone in class? Consider differentiated instruction—a method you may have heard about but haven’t explored, which is why you’re here. In this article, learn exactly what it means, how it works, and the pros and cons.

Definition of differentiated instruction

Carol Ann Tomlinson is a leader in the area of differentiated learning and professor of educational leadership, foundations, and policy at the University of Virginia. Tomlinson describes differentiated instruction as factoring students’ individual learning styles and levels of readiness first before designing a lesson plan. Research on the effectiveness of differentiation shows this method benefits a wide range of students, from those with learning disabilities to those who are considered high ability.

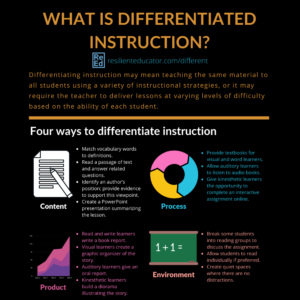

Differentiating instruction may mean teaching the same material to all students using a variety of instructional strategies, or it may require the teacher to deliver lessons at varying levels of difficulty based on the ability of each student.

Teachers who practice differentiation in the classroom may:

- Design lessons based on students’ learning styles.

- Group students by shared interest, topic, or ability for assignments.

- Assess students’ learning using formative assessment.

- Manage the classroom to create a safe and supportive environment.

- Continually assess and adjust lesson content to meet students’ needs.

History of differentiated instruction

The roots of differentiated instruction go all the way back to the days of the one-room schoolhouse, where one teacher had students of all ages in one classroom. As the educational system transitioned to grading schools, it was assumed that children of the same age learned similarly. However in 1912, achievement tests were introduced, and the scores revealed the gaps in student’s abilities within grade levels.

In 1975, Congress passed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), ensuring that children with disabilities had equal access to public education. To reach this student population, many educators used differentiated instruction strategies. Then came the passage of No Child Left Behind in 2000, which further encouraged differentiated and skill-based instruction—and that’s because it works. Research by educator Leslie Owen Wilson supports differentiating instruction within the classroom, finding that lecture is the least effective instructional strategy, with only 5 to 10 percent retention after 24 hours. Engaging in a discussion, practicing after exposure to content, and teaching others are much more effective ways to ensure learning retention.

Four ways to differentiate instruction

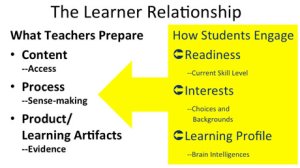

According to Tomlinson, teachers can differentiate instruction through four ways: 1) content, 2) process, 3) product, and 4) learning environment.

As you already know, fundamental lesson content should cover the standards of learning set by the school district or state educational standards. But some students in your class may be completely unfamiliar with the concepts in a lesson, some students may have partial mastery, and some students may already be familiar with the content before the lesson begins.

What you could do is differentiate the content by designing activities for groups of students that cover various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (a classification of levels of intellectual behavior going from lower-order thinking skills to higher-order thinking skills). The six levels are: remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating.

Students who are unfamiliar with a lesson could be required to complete tasks on the lower levels: remembering and understanding. Students with some mastery could be asked to apply and analyze the content, and students who have high levels of mastery could be asked to complete tasks in the areas of evaluating and creating.

Examples of differentiating activities:

- Match vocabulary words to definitions.

- Read a passage of text and answer related questions.

- Think of a situation that happened to a character in the story and a different outcome.

- Differentiate fact from opinion in the story.

- Identify an author’s position and provide evidence to support this viewpoint.

- Create a PowerPoint presentation summarizing the lesson.

Each student has a preferred learning style, and successful differentiation includes delivering the material to each style: visual, auditory and kinesthetic, and through words. This process-related method also addresses the fact that not all students require the same amount of support from the teacher, and students could choose to work in pairs, small groups, or individually. And while some students may benefit from one-on-one interaction with you or the classroom aide, others may be able to progress by themselves. Teachers can enhance student learning by offering support based on individual needs.

Examples of differentiating the process:

- Provide textbooks for visual and word learners.

- Allow auditory learners to listen to audio books.

- Give kinesthetic learners the opportunity to complete an interactive assignment online.

The product is what the student creates at the end of the lesson to demonstrate the mastery of the content. This can be in the form of tests, projects, reports, or other activities. You could assign students to complete activities that show mastery of an educational concept in a way the student prefers, based on learning style.

Examples of differentiating the end product:

- Read and write learners write a book report.

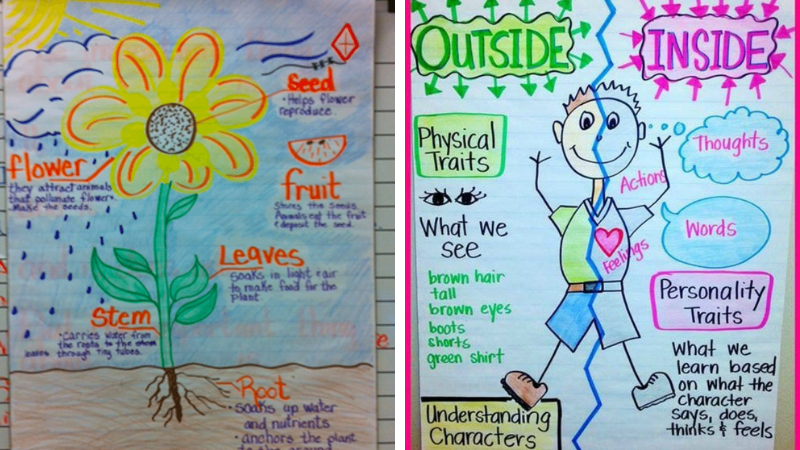

- Visual learners create a graphic organizer of the story.

- Auditory learners give an oral report.

- Kinesthetic learners build a diorama illustrating the story.

4. Learning environment

The conditions for optimal learning include both physical and psychological elements. A flexible classroom layout is key, incorporating various types of furniture and arrangements to support both individual and group work. Psychologically speaking, teachers should use classroom management techniques that support a safe and supportive learning environment.

Examples of differentiating the environment:

- Break some students into reading groups to discuss the assignment.

- Allow students to read individually if preferred.

- Create quiet spaces where there are no distractions.

Pros and cons of differentiated instruction

The benefits of differentiation in the classroom are often accompanied by the drawback of an ever-increasing workload. Here are a few factors to keep in mind:

- Research shows differentiated instruction is effective for high-ability students as well as students with mild to severe disabilities.

- When students are given more options on how they can learn material, they take on more responsibility for their own learning.

- Students appear to be more engaged in learning, and there are reportedly fewer discipline problems in classrooms where teachers provide differentiated lessons.

- Differentiated instruction requires more work during lesson planning, and many teachers struggle to find the extra time in their schedule.

- The learning curve can be steep and some schools lack professional development resources.

- Critics argue there isn’t enough research to support the benefits of differentiated instruction outweighing the added prep time.

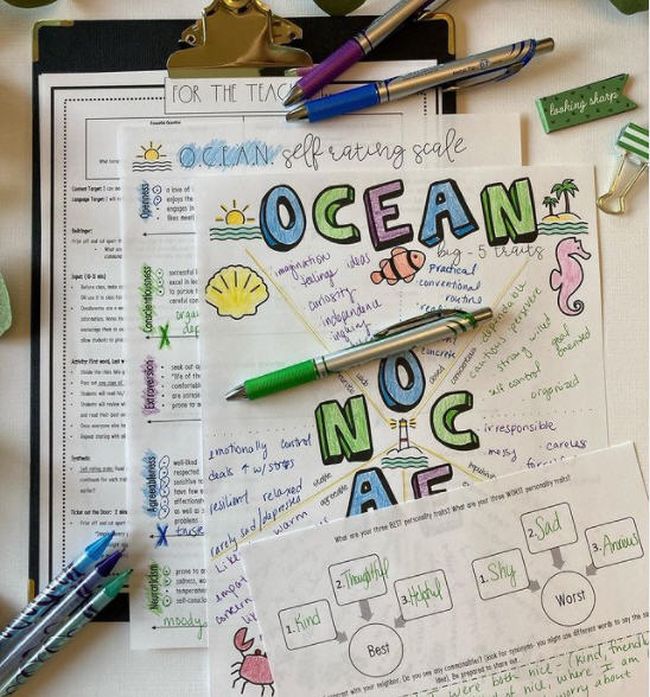

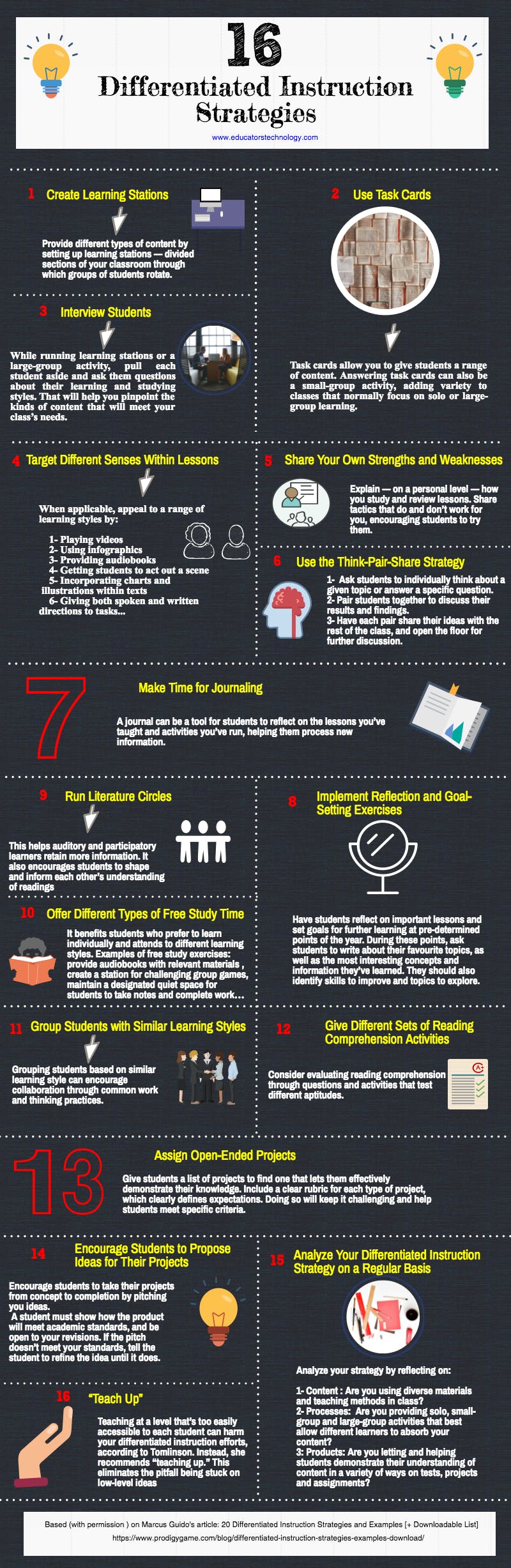

Differentiated instruction strategies

What differentiated instructional strategies can you use in your classroom? There are a set of methods that can be tailored and used across the different subjects. According to Kathy Perez (2019) and the Access Center those strategies are tiered assignments, choice boards, compacting, interest centers/groups, flexible grouping, and learning contracts. Tiered assignments are designed to teach the same skill but have the students create a different product to display their knowledge based on their comprehension skills. Choice boards allow students to choose what activity they would like to work on for a skill that the teacher chooses. On the board are usually options for the different learning styles; kinesthetic, visual, auditory, and tactile. Compacting allows the teacher to help students reach the next level in their learning when they have already mastered what is being taught to the class. To compact the teacher assesses the student’s level of knowledge, creates a plan for what they need to learn, excuses them from studying what they already know, and creates free time for them to practice an accelerated skill.

Interest centers or groups are a way to provide autonomy in student learning. Flexible grouping allows the groups to be more fluid based on the activity or topic. Finally, learning contracts are made between a student and teacher, laying out the teacher’s expectations for the necessary skills to be demonstrated and the assignments required components with the student putting down the methods they would like to use to complete the assignment. These contracts can allow students to use their preferred learning style, work at an ideal pace and encourages independence and planning skills. The following are strategies for some of the core subject based on these methods.

Differentiated instruction strategies for math

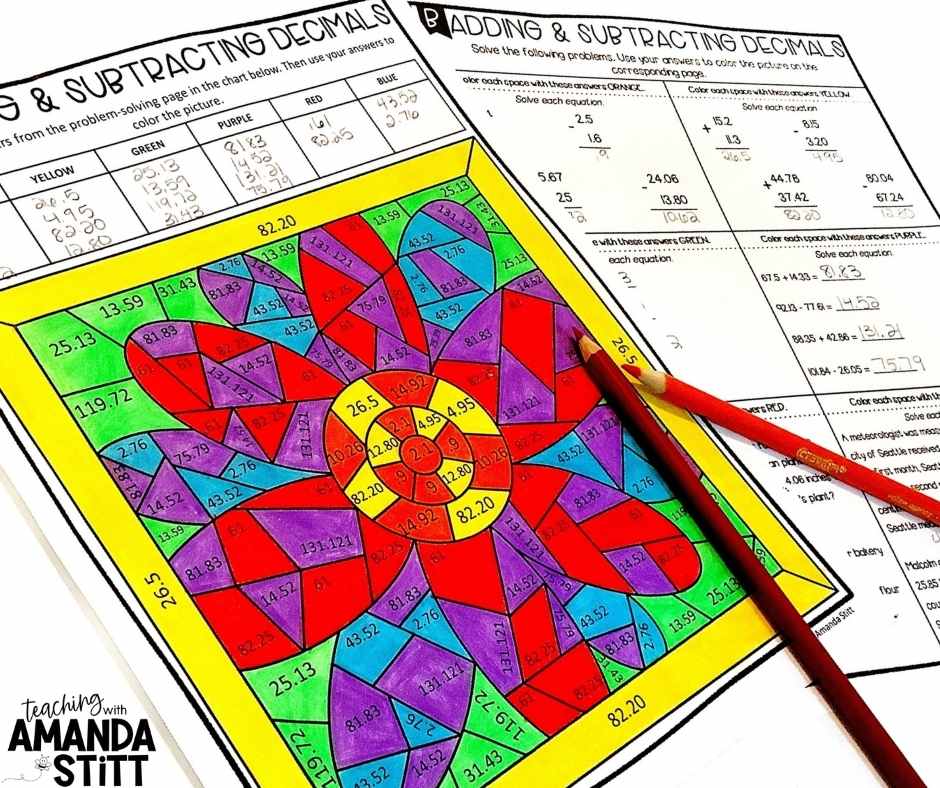

- Provide students with a choice board. They could have the options to learn about probability by playing a game with a peer, watching a video, reading the textbook, or working out problems on a worksheet.

- Teach mini lessons to individuals or groups of students who didn’t grasp the concept you were teaching during the large group lesson. This also lends time for compacting activities for those who have mastered the subject.

- Use manipulatives, especially with students that have more difficulty grasping a concept.

- Have students that have already mastered the subject matter create notes for students that are still learning.

- For students that have mastered the lesson being taught, require them to give in-depth, step-by-step explanation of their solution process, while not being rigid about the process with students who are still learning the basics of a concept if they arrive at the correct answer.

Differentiated instruction strategies for science

- Emma McCrea (2019) suggests setting up “Help Stations,” where peers assist each other. Those that have more knowledge of the subject will be able to teach those that are struggling as an extension activity and those that are struggling will receive.

- Set up a “question and answer” session during which learners can ask the teacher or their peers questions, in order to fill in knowledge gaps before attempting the experiment.

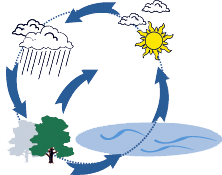

- Create a visual word wall. Use pictures and corresponding labels to help students remember terms.

- Set up interest centers. When learning about dinosaurs you might have an “excavation” center, a reading center, a dinosaur art project that focuses on their anatomy, and a video center.

- Provide content learning in various formats such as showing a video about dinosaurs, handing out a worksheet with pictures of dinosaurs and labels, and providing a fill-in-the-blank work sheet with interesting dinosaur facts.

Differentiated instruction strategies for ELL

- ASCD (2012) writes that all teachers need to become language teachers so that the content they are teaching the classroom can be conveyed to the students whose first language is not English.

- Start by providing the information in the language that the student speaks then pairing it with a limited amount of the corresponding vocabulary in English.

- Although ELL need a limited amount of new vocabulary to memorize, they need to be exposed to as much of the English language as possible. This means that when teaching, the teacher needs to focus on verbs and adjectives related to the topic as well.

- Group work is important. This way they are exposed to more of the language. They should, however, be grouped with other ELL if possible as well as given tasks within the group that are within their reach such as drawing or researching.

Differentiated instruction strategies for reading

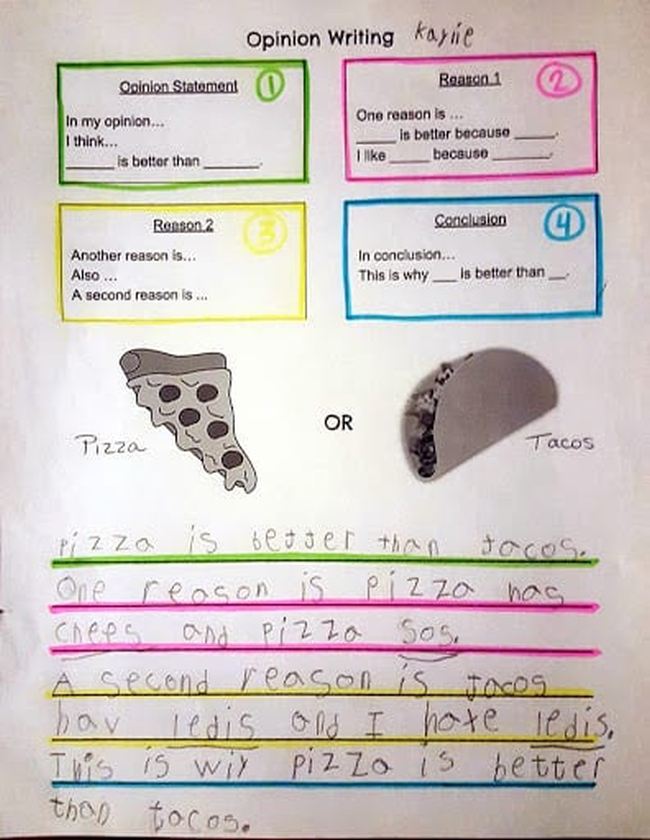

- Tiered assignments can be used in reading to allow the students to show what they have learned at a level that suites them. One student might create a visual story board while another student might write a book report.

- Reading groups can pick a book based on interest or be assigned based on reading level

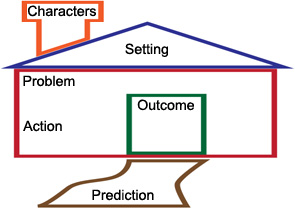

- Erin Lynch (2020) suggest that teachers scaffold instruction by giving clear explicit explanations with visuals. Verbally and visually explain the topic. Use anchor charts, drawings, diagrams, and reference guides to foster a clearer understanding. If applicable, provide a video clip for students to watch.

- Utilize flexible grouping. Students might be in one group for phonics based on their assessed level but choose to be in another group for reading because they are more interested in that book.

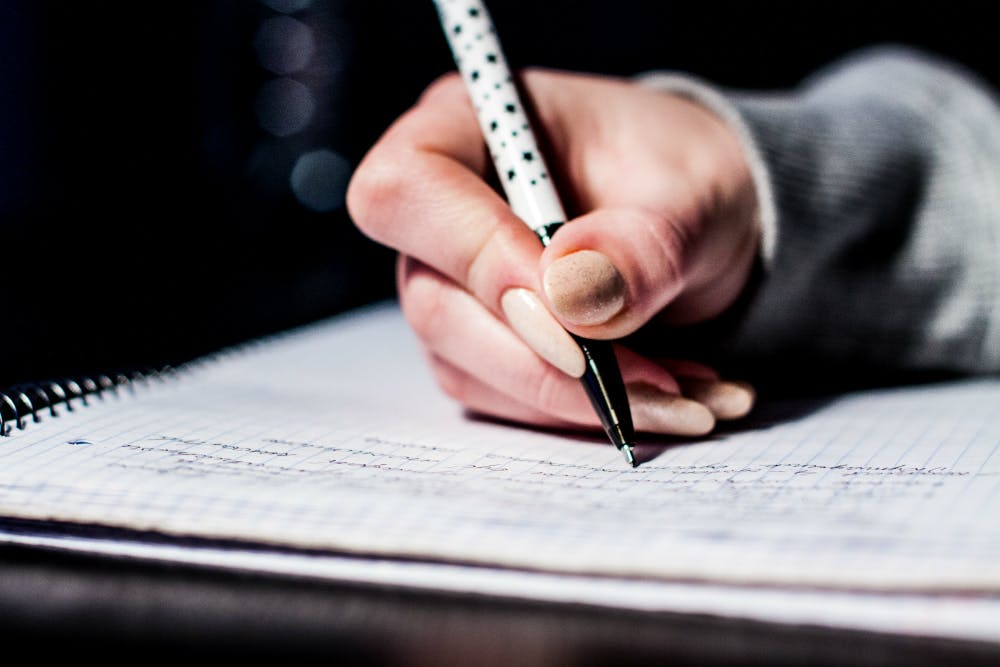

Differentiated instruction strategies for writing

- Hold writing conferences with your students either individually or in small groups. Talk with them throughout the writing process starting with their topic and moving through grammar, composition, and editing.

- Allow students to choose their writing topics. When the topic is of interest, they will likely put more effort into the assignment and therefore learn more.

- Keep track of and assess student’s writing progress continually throughout the year. You can do this using a journal or a checklist. This will allow you to give individualized instruction.

- Hand out graphic organizers to help students outline their writing. Try fill-in-the-blank notes that guide the students through each step of the writing process for those who need additional assistance.

- For primary grades give out lined paper instead of a journal. You can also give out differing amounts of lines based on ability level. For those who are excelling at writing give them more lines or pages to encourage them to write more. For those that are still in the beginning stages of writing, give them less lines so that they do not feel overwhelmed.

Differentiated instruction strategies for special education

- Use a multi-sensory approach. Get all five senses involved in your lessons, including taste and smell!

- Use flexible grouping to create partnerships and teach students how to work collaboratively on tasks. Create partnerships where the students are of equal ability, partnerships where once the student will be challenged by their partner and another time they will be pushing and challenging their partner.

- Assistive technology is often an important component of differential instruction in special education. Provide the students that need them with screen readers, personal tablets for communication, and voice recognition software.

- The article Differentiation & LR Information for SAS Teachers suggests teachers be flexible when giving assessments “Posters, models, performances, and drawings can show what they have learned in a way that reflects their personal strengths”. You can test for knowledge using rubrics instead of multiple-choice questions, or even build a portfolio of student work. You could also have them answer questions orally.

- Utilize explicit modeling. Whether its notetaking, problem solving in math, or making a sandwich in home living, special needs students often require a step-by-step guide to make connections.

References and resources

- https://www.thoughtco.com/differentiation-instruction-in-special-education-3111026

- https://sites.google.com/site/lrtsas/differentiation/differentiation-techniques-for-special-education

- https://www.solutiontree.com/blog/differentiated-reading-instruction/

- https://www.readingrockets.org/article/differentiated-instruction-reading

- https://www.sadlier.com/school/ela-blog/13-ideas-for-differentiated-reading-instruction-in-the-elementary-classroom

- https://inservice.ascd.org/seven-strategies-for-differentiating-instruction-for-english-learners/

- https://www.cambridge.org/us/education/blog/2019/11/13/three-approaches-differentiation-primary-science/

- https://www.brevardschools.org/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=6174&dataid=8255&FileName=Differentiated_Instruction_in_Secondary_Mathematics.pdf

Books & Videos about differentiated instruction by Carol Ann Tomlinson and others

- The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, 2nd Edition

- Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Marcia B. Imbeau

- The Differentiated School: Making Revolutionary Changes in Teaching and Learning – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Kay Brimijoin, and Lane Narvaez

- Integrating Differentiated Instruction and Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Jay McTighe

- Differentiation in Practice Grades K-5: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Caroline Cunningham Eidson

- Differentiation in Practice Grades 5–9: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Caroline Cunningham Eidson

- Differentiation in Practice Grades 9–12: A Resource Guide for Differentiating Curriculum – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Cindy A. Strickland

- Fulfilling the Promise of the Differentiated Classroom: Strategies and Tools for Responsive Teaching – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Leadership for Differentiating Schools and Classrooms – Carol Ann Tomlinson and Susan Demirsky Allan

- How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms, 3rd Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom by Carol Ann Tomlinson and Tonya R. Moon

- How To Differentiate Instruction In Mixed Ability Classrooms 2nd Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms 3rd Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom Paperback – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Tonya R. Moon

- Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom (Professional Development) 1st Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Marcia B. Imbeau

- The Differentiated School: Making Revolutionary Changes in Teaching and Learning 1st Edition by Carol Ann Tomlinson, Kay Brimijoin, Lane Narvaez

- Differentiation and the Brain: How Neuroscience Supports the Learner-Friendly Classroom – David A. Sousa, Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Leading for Differentiation: Growing Teachers Who Grow Kids – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Michael Murphy

- An Educator’s Guide to Differentiating Instruction. 10th Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson, James M. Cooper

- A Differentiated Approach to the Common Core: How do I help a broad range of learners succeed with a challenging curriculum? – Carol Ann Tomlinson, Marcia B. Imbeau

- Managing a Differentiated Classroom: A Practical Guide – Carol Tomlinson, Marcia Imbeau

- Differentiating Instruction for Mixed-Ability Classrooms: An ASCD Professional Inquiry Kit Pck Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Using Differentiated Classroom Assessment to Enhance Student Learning (Student Assessment for Educators) 1st Edition – Tonya R. Moon, Catherine M. Brighton, Carol A. Tomlinson

- The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners 1st Edition – Carol Ann Tomlinson

You may also like to read

- Creative Academic Instruction: Music Resources for the Classroom

- How Teachers Use Student Data to Improve Instruction

- Advice on Positive Classroom Management that Works

- Five Skills Online Teachers Need for Classroom Instruction

- 3 Examples of Effective Classroom Management

- Advice on Improving your Elementary Math Instruction

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Curriculum and Instruction , Diversity , Engaging Activities , New Teacher , Pros and Cons

- Certificates in Administrative Leadership

- Trauma-Informed Practices in School: Teaching...

- Certificates for Reading Specialist

Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction involves teaching in a way that meets the different needs and interests of students using varied course content, activities, and assessments.

Teaching differently to different students

Differentiated Instruction (DI) is fundamentally the attempt to teach differently to different students, rather than maintain a one-size-fits-all approach to instruction. Other frameworks, such as Universal Design for Learning , enjoin instructors to give students broad choice and agency to meet their diverse needs and interests. DI distinctively emphasizes instructional methods to promote learning for students entering a course with different readiness for, interest in, and ways of engaging with course learning based on their prior learning experiences ( Dosch and Zidon 2014).

Successful implementation of DI requires ongoing training, assessment, and monitoring (van Geel et al. 2019) and has been shown to be effective in meeting students’ different needs, readiness levels, and interests (Turner et al. 2017). Below, you can find six categories of DI instructional practices that span course design and live teaching.

While some of the strategies are best used together, not all of them are meant to be used at once, as the flexibility inherent to these approaches means that some of them are diverging when used in combination (e.g., constructing homogenous student groups necessitates giving different types of activities and assessments; constructing heterogeneous student groups may pair well with peer tutoring) (Pozas et al. 2020). The learning environment the instructor creates with students has also been shown to be an important part of successful DI implementation (Shareefa et al. 2019).

Differentiated Assessment

Differentiated assessment is an aspect of Differentiated Instruction that focuses on tailoring the ways in which students can demonstrate their progress to their varied strengths and ways of learning. Instead of testing recall of low-level information, instructors should focus on the use of knowledge and complex reasoning. Differentiation should inform not only the design of instructors’ assessments, but also how they interpret the results and use them to inform their DI practices.

More Team Project Ideas

Steps to consider

There are generally considered to be six categories of useful differentiated instruction and assessment practices (Pozas & Schneider 2019):

- Making assignments that have tasks and materials that are qualitatively and/or quantitatively varied (according to “challenge level, complexity, outcome, process, product, and/or resources”) (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) It’s helpful to assess student readiness and interest by collecting data at the beginning of the course, as well as to conduct periodic check-ins throughout the course (Moallemi 2023 & Pham 2011)

- Making student working groups that are intentionally chosen (that are either homogeneous or heterogeneous based on “performance, readiness, interests, etc.”) (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) Examples of how to make different student groups provided by Stanford CTL (Google Doc)

- Making tutoring systems within the working group where students teach each other (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) For examples of how to support peer instruction, and the benefits of doing so, see for example Tullis & Goldstone 2020 and Peer Instruction for Active Learning (LSA Technology Services, University of Michigan)

- Making non-verbal learning aids that are staggered to provide support to students in helping them get to the next step in the learning process (only the minimal amount of information that is needed to help them get there is provided, and this step is repeated each time it’s needed) (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible) Non-verbal cue cards support students’ self-regulation, as they can monitor and control their progress as they work (Pozas & Schneider 2019)

- Making instructional practices that ensure all students meet at least the minimum standards and that more advanced students meet higher standards , which involves monitoring students’ learning process carefully (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible; IP Module 5: Giving Inclusive Assessments) This type of approach to student assessment can be related to specifications grading, where students determine the grade they want and complete the modules that correspond to that grade, offering additional motivation to and reduced stress for students and additional flexibility and time-saving practices to instructors (Hall 2018)

- Making options that support student autonomy in being responsible for their learning process and choosing material to work on (e.g., students can choose tasks, project-based learning, portfolios, and/or station work, etc.) (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible) This option, as well as the others, fits within a general Universal Design Learning framework , which is designed to improve learning for everyone using scientific insights about human learning

Hall, M (2018). “ What is Specifications Grading and Why Should You Consider Using It? ” The Innovator Instructor blog, John Hopkins University Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation.

Moallemi, R. (2023). “ The Relationship between Differentiated Instruction and Learner Levels of Engagement at University .” Journal of Research in Integrated Teaching and Learning (ahead of print).

Pham, H. (2011). “ Differentiated Instruction and the Need to Integrate Teaching and Practice .” Journal of College Teaching and Learning , 9(1), 13-20.

Pozas, M. & Schneider, C. (2019). " Shedding light into the convoluted terrain of differentiated instruction (DI): Proposal of a taxonomy of differentiated instruction in the heterogeneous classroom ." Open Education Studies , 1, 73–90.

Pozas, M., Letzel, V. and Schneider, C. (2020). " Teachers and differentiated instruction: exploring differentiation practices to address student diversity ." Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs , 20: 217-230.

Shareefa, M. et al. (2019). “ Differentiated Instruction: Definition and Challenging Factors Perceived by Teachers .” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Special Education (ICSE 2019).

Tullis, J.G. & Goldstone, R.L. (2020). “ Why does peer instruction benefit student learning? ”, Cognitive Research 5 .

Turner, W.D., Solis, O.J., and Kincade, D.H. (2017). “ Differentiating Instruction for Large Classes in Higher Education ”, International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 29(3), 490-500.

van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher A.J. (2019). “Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction”, School Effectiveness and School Improvement , 30:1, 51-67, DOI: 10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013

What Is Differentiated Instruction?

Instruction is tailored to meet all students' needs, interests and strengths.

Getty Images

The most challenging task for differentiated learning is the execution in the classroom.

No two students are alike, including when it comes to their academic strengths and how exactly they learn best.

That's why many educators have sought to adopt more inclusive teaching practices, one being differentiated instruction – a broad term that usually refers to a teaching approach where instruction is tailored to meet all students' needs, interests and strengths.

"When you have a one-size-fits-all approach, it connects to your high and some of your middle learners. But it doesn't connect to some of your lower learners. So this way, we are able to grab all levels of learners," says Dave Steckler, principal at Red Trail Elementary School in North Dakota and president of the National Association of Elementary School Principals. "Differentiated instruction gives our students success, which promotes that love to learn."

How Differentiated Instruction Works

Differentiated instruction may look different in every classroom, grade, school or district. But according to experts, teachers can differentiate instruction in four areas: content, process, product and learning environment.

Content differentiation is when teachers provide learning activities based on where the student is academically, while process occurs when teachers differentiate the mode of learning, says Becky Pringle, a middle school science teacher for 30 years and now president of the National Education Association, the nation's largest teachers' union.

For students with dyslexia , for instance, it may be difficult to simultaneously listen and take notes. A differentiated instruction approach might adjust the process by passing out a copy of the class notes for students to follow along with, says David Arencibia, principal at Colleyville Middle School in Texas.

Product differentiation refers to ways students can demonstrate what they know, whether that's through varying assignments , projects or exams. For example, students may be given several options to show that they understood a book read in class , such as a writing an essay, drawing or creating a poem.

The physical space and feeling of a classroom can also impact learning. A differentiated classroom may have flexible seating. Students in an English class, for instance, may get the option to go to other learning areas, such as the library, to read in a more comfortable area if they so choose, Arencibia says.

"Think of yourself as a reader," he says. "Do you want to be sitting in a hard desk with a specific type of lighting where it's kind of uncomfortable or would you rather be sitting on the couch with special lighting? We differentiate even our learning environments to really be conducive to really get the most out of our learning for our students."

Differentiated Instruction vs. Other Approaches

More "traditional" approaches to learning often entail a teacher lecturing at the front of the classroom with an accompanying PowerPoint presentation, where students are asked to listen and take notes.

Children in a differentiated classroom are also all working toward the same learning goals, says Carol A. Tomlinson, professor emeritus at the University of Virginia’ s School of Education. But "they won't all be doing the same work in the same way over the same time period with the same support."

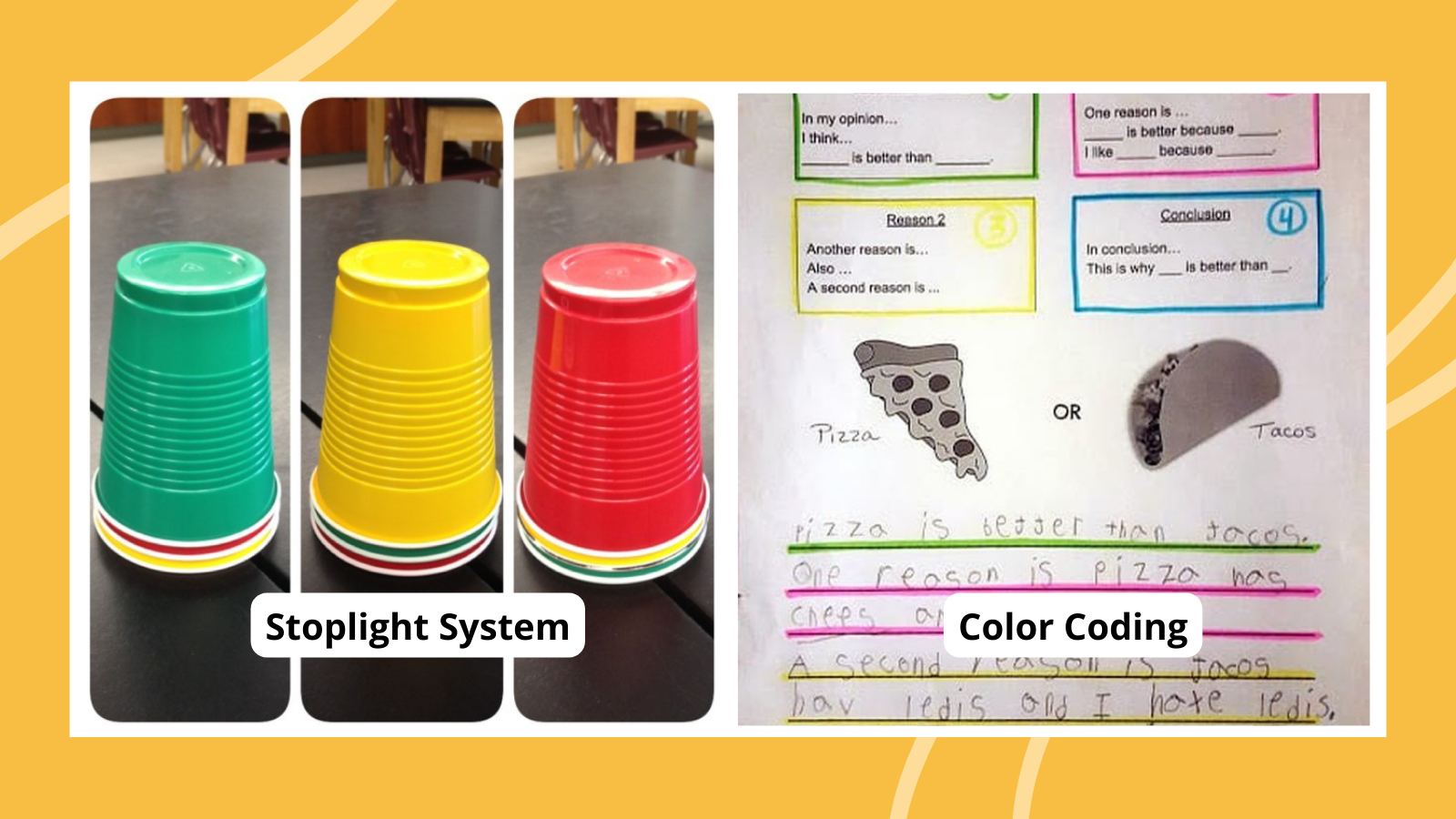

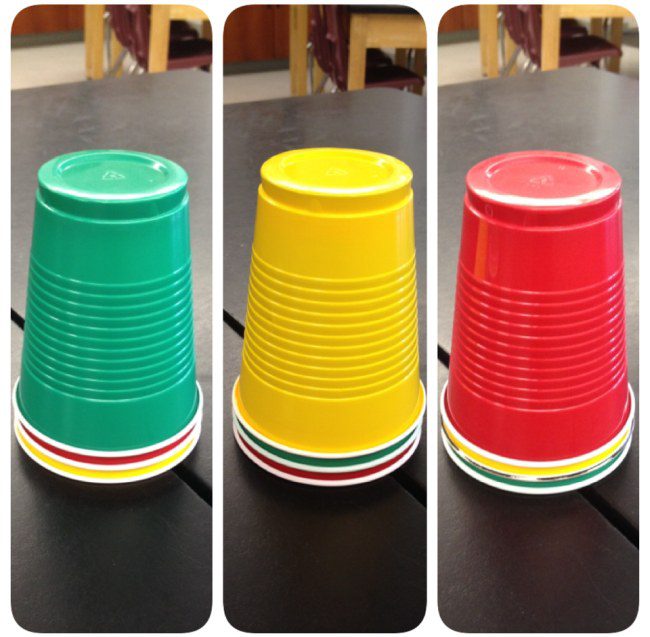

Teachers might use rotating work stations to divide students based on skill level, so students complete assignments that correlate with their academic level and needs. This can be done in a confidential way, such as through color-coding, in order to ensure students can't tell apart their levels, Arencibia says.

How to Know if Differentiated Instruction Is Being Done Well

Though many experts say differentiated instruction is beneficial, it can be challenging to execute in the classroom – in part because teachers have to really know the ins and outs of each student.

"That should be something that all instructors should be doing anyway, but sometimes it becomes automated and you are just there to teach and get out and go home," says Joseph Lathan, professor of practice and director of online programs in the department of learning and teaching at the University of San Diego in California. "You have to spend the time to know your students to be able to best help them."

There's also immense pressure for teachers around standardized tests, Tomlinson says. "They feel like all they can do is go into the classroom, start covering the material, cover it as fast as they can and at the end of the year say, 'I did it, I made it through.' We don't have any reason to believe that's effective teaching or learning."

Experts says parents should be feel good about differentiation going on if their child can explain their learning goals, shows enthusiasm about learning and talks about working in a variety of groups and having a choice of assignments.

"It's not intended to be in your face all the time. It's intended to be subtle and smooth," Tomlinson says.

See the 2022 Best Public High Schools

Tags: K-12 education , students , elementary school , high school , middle school

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

College Admissions Playbook

You May Also Like

Choosing a high school: what to consider.

Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

Map: Top 100 Public High Schools

Sarah Wood and Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

States With Highest Test Scores

Sarah Wood April 23, 2024

Metro Areas With Top-Ranked High Schools

A.R. Cabral April 23, 2024

U.S. News Releases High School Rankings

Explore the 2024 Best STEM High Schools

Nathan Hellman April 22, 2024

See the 2024 Best Public High Schools

Joshua Welling April 22, 2024

Ways Students Can Spend Spring Break

Anayat Durrani March 6, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

How to Perform Well on SAT, ACT Test Day

Cole Claybourn Feb. 13, 2024

Differentiated Instruction: A Primer

- Share article

How can a teacher keep a reading class of 25 on the same page when four students have dyslexia, three students are learning English as a second language, two others read three grade levels ahead, and the rest have widely disparate interests and degrees of enthusiasm about reading?

What is Differentiated Instruction?

“Differentiated instruction”—the process of identifying students’ individual learning strengths, needs, and interests and adapting lessons to match them—has become a popular approach to helping diverse students learn together. But the field of education is filled with varied and often conflicting definitions of what the practice looks like, and critics argue it requires too much training and additional work for teachers to be implemented consistently and effectively.

Differentiated Instruction Definition

The process of identifying students’ individual learning strengths, needs, and interests and adapting lessons to match them

Differentiation has much in common with many other instructional models: It has been compared to response-to-intervention models, as teachers vary their approach to the same material with different students in the same classroom; data-driven instruction, as individual students are frequently assessed or otherwise monitored, with instruction tweaked in response; and scaffolding, as assignments are intended to be structured to help students of different ability and interest levels meet the same goals.

Federal education laws and regulations do not generally set out requirements for how schools and teachers should “differentiate” instruction. However, in its 2010 National Education Technology Plan , the U.S. Department of Education lays out a framework that places differentiated teaching under the larger umbrella of “personalized learning,” instruction tailored to students’ individual learning needs, preferences, and interests. This framework assumes that all students in a heterogeneous classroom will have the same learning goals, but:

- “Individualization” tailors instruction by time . A teacher may break the material into smaller steps and allow students to master these steps at different paces; skipping topics they can prove they have mastered, while getting more help on those that prove difficult. This model has been used in iterations as far back as the late Robert Glaser’s Individually Prescribed Instruction in the 1970s, an approach which pairs diagnostic tests with objectives for mastery that is intended to help students progress through material at their own pace.

- “Differentiation” tailors instruction by presentation . A teacher may vary the method and assignments covering the material to adjust to students’ strengths, needs, and interests. For example, a teacher may allow an introverted student to write an essay on a historical topic while a more outgoing student gives an oral presentation on the same subject.

That distinction is accepted by some, though far from all, in the field.

The ambiguity has led to widespread confusion and debate over what differentiated instruction looks like in practice, and how its effectiveness can be evaluated.

For example, a 2005 study for the National Research Center on Gifted and Talented, which tracked implementation of “differentiation” over three years , found that the “vast majority” of teachers never moved beyond traditional direct lectures and seat work for students.

“Results suggest that differentiation of instruction and assessment are complex endeavors requiring extended time and concentrated effort to master,” the authors conclude. “Add to this complexity current realities of school such as large class sizes, limited resource materials, lack of planning time, lack of structures in place to allow collaboration with colleagues, and ever-increasing numbers of teacher responsibilities, and the tasks become even more daunting.”

Evolution of the Concept

Differentiated instruction as a concept evolved in part from instructional methods advocated for gifted students and in part as an alternative to academic “tracking,” or separating students of different ability levels into groups or classes. In the 1983 book, Individual Differences and the Common Curriculum , Thomas S. Popkewitz discusses differentiation in the context of “Individually Guided Education, … a management plan for pacing children through a standardized, objective-based curriculum” that would include small-group work, team teaching, objective-based testing, and monitoring of student progress.

Carol Ann Tomlinson, a co-director of the Institutes on Academic Diversity at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, and the author of The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners , 2nd Edition (ASCD, 2014) and Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom (ASCD, 2013) argues that differentiation is, at its base, not an approach but a basic tenet of good instruction, in which a teacher develops relationships with his or her students and presents materials and assignments in ways that respond to the student’s interests and needs.

Differentiated Instruction Strategies

In theory—though critics allege not in practice—differentiation does not involve creating separate lesson plans for individual students for a given unit.

Ms. Tomlinson argues that differentiation requires more than creating options for assignments or presenting content both graphically and with hands-on projects, for example. Rather, to differentiate a unit on Rome, a teacher might consider both specific terms and overarching themes and concepts she wants students to learn, and offer a series of individual and group assignments of various levels of complexity to build those concepts and allow students to demonstrate their understanding in multiple ways, such as journal entries, oral presentations, creating costumes, and so on. In different parts of a unit students may be working with students who share their interests or have different ones, and with students who are at the same or different ability levels.

During the 1990s, teachers were also encouraged to present material differently according to a student’s “learning style”—for example, visual, auditory, or kinesthetic. But while there have been studies that show students remember more when the same material is presented and reinforced in multiple ways, recent research reviews have found no evidence that individual students can be categorized as learning best through a single type of presentation.

Rick Wormeli, an education consultant and the author of Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessment and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom , instead suggests in a 2011 essay in the journal Middle Ground that teachers differentiate based on “learner profiles” : “A learner profile is a set of observations about a student that includes any factor that affects his or her learning, including family dynamics, transiency rate, physical health, emotional health, comfort with technology, leadership qualities, personal interests, and so much more.”

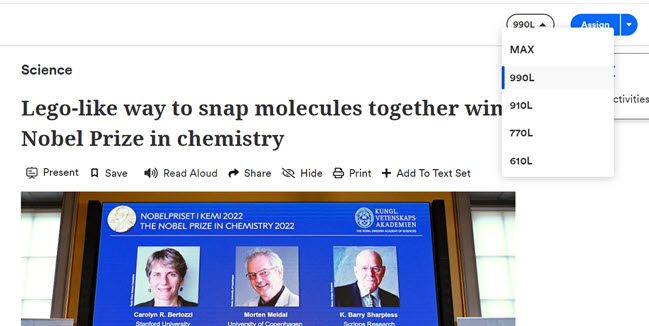

Impacts of Technology

Differentiated and personalized instructional models have also evolved with technological advances, which make it easier to develop and monitor education plans for dozens of students at the same time. The influence of differentiation on school-level programs can be seen in “early warning systems” and student “dashboards” that aim to track individual student performance in real time, as well as initiatives in some schools to develop and monitor individualized learning plans with the student, his or her teachers, and parents.

Advocates of hybrid education models, such as the “flipped classroom” —in which students watch lectures and read material at home and perform practice that would normally be homework during class time—have suggested this could help teachers differentiate by recording and archiving different lectures that students could watch and rewatch as needed, and providing more one-on-one time during class.

Professional Development

By any account, differentiation is considered a complex approach to implement, requiring extensive and ongoing professional development for teachers and administrators.

It required teachers to confront and dismantle their existing, persistent beliefs about teaching and learning ...

In the 2005 longitudinal study that found no consistent implementation of differentiation, researchers noted that “many aspects of differentiation of instruction and assessment (e.g., assigning different work to different students, promoting greater student independence in the classroom) challenged teachers’ beliefs about fairness, about equity, and about how classrooms should be organized to allow students to learn most effectively. As a result, for most teachers, learning to differentiate entailed more than simply learning new practices. It required teachers to confront and dismantle their existing, persistent beliefs about teaching and learning, beliefs that were in large part shared and reinforced by other teachers, principals, parents, the community, and even students.”

In the 2009 book, Professional Development for Differentiating Instruction , Cindy A. Strickland notes that most schools do not provide sufficient training for new and experienced teachers in differentiating instruction.

Ms. Tomlinson said that teachers can begin to differentiate instruction simply by learning more about their students and trying to tailor their teaching as much as they find feasible. “Every significant endeavor seems too hard if we look only at the expert’s product. ... The success of all these ‘seasoned’ people stemmed largely from three factors: They started down a path. They wanted to do better. They kept working toward their goal.”

Including students of disparate abilities and interests also requires the teacher to rethink expectations for all students: “If a teacher uses flexible grouping lesson by lesson and does not assume a student has prior knowledge because he is a ‘higher’ student but really assesses and groups, based on need sometimes and other times by interest, the students will get what they need,” Melinda L. Fattig, a nationally recognized educator and a co-author of the 2008 book Co-Teaching in the Differentiated Classroom , told Teacher magazine that year.

In practice, differentiation is such a broad and multifaceted approach that it has proven difficult to implement properly or study empirically, critics say.

In a 2010 report by the research group McREL, author Bryan Goodwin notes that “to date, no empirical evidence exists to confirm that the total package (e.g., conducting ongoing assessments of student abilities, identifying appropriate content based on those abilities, using flexible grouping arrangements for students, and varying how students can demonstrate proficiency in their learning) has a positive impact on student achievement.” He adds: “One reason for this lack of evidence may simply be that no large-scale, scientific study of differentiated instruction has been conducted.” However, Mr. Goodwin pointed to the 2009 book Visible Learning , which synthesized studies of more than 600 models of personalizing learning based on student interests and prior performance, and found them not much better than general classroom instruction for improving students’ academic performance.

Both in planning time and instructional time, differentiation takes longer than using a single lesson plan for a given topic, and many teachers attempting to differentiate have reported feeling overwhelmed and unable to reach each student equally.

In a 2010 Education Week Commentary essay , Michael J. Schmoker, the author of the 2006 book, Results NOW: How We Can Achieve Unprecedented Improvements in Teaching and Learning , says attempts to differentiate instruction frustrated teachers and “seemed to complicate teachers’ work, requiring them to procure and assemble multiple sets of materials” leading to “dumbed-down” teaching.

Likewise, some advocates of gifted education, such as James R. Delisle, have argued that advanced students still are not challenged enough in a differentiated environment, which may vary in the presentation of material but not necessarily in the pace of instruction. He argues that “differentiation in practice is harder to implement in a heterogeneous classroom than it is to juggle with one arm tied behind your back.”

“There is no one book, video, presenter, or website that will show everyone how to differentiate instruction. Let’s stop looking for it. One size rarely fits all. Our classrooms are too diverse and our communities too important for such simplistic notions,” Mr. Wormeli said in an interview with Education Week blogger Larry Ferlazzo .

“Instead, let’s realize what differentiation really is: highly effective teaching, which is complex and interwoven; no one element defining it.”

A version of this article appeared in the February 04, 2015 edition of Education Week

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

What is Differentiated Instruction?

- History of Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated Instruction: Content, Process and Product

Differentiated instruction: classroom strategies and examples, pro & cons of differentiated instruction, differentiated instruction faq, innovative techniques for transforming your classroom.

Teachers know better than anyone that students each have their own unique gifts and challenges; interests, aptitudes and learning styles. Differentiated instruction is the practice of developing an understanding of how each student learns best, and then tailoring instruction to meet students’ individual needs.

“I think differentiated instruction actually is just teaching with the child in mind,” writes Carol Ann Tomlinson, an author and teacher regarded as a pioneer in differentiated instruction. She describes the practice as “a way of thinking about teaching which suggests that we establish very clear learning goals, that are very substantial, and then that we teach with an eye on the student.”

In her book, “How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms,” she explains: “Kids of the same age aren’t all alike when it comes to learning any more than they are alike in terms of size, hobbies, personality, or food preferences. … In a classroom with little or no differentiated instruction, only student similarities seem to take center stage. In a differentiated classroom, commonalities are acknowledged and built upon, and student differences also become important elements in teaching and learning.”

At its most basic level, Tomlinson continues, “differentiating instruction means ‘shaking up’ what goes on in the classroom so that students have multiple options for taking in information, making sense of ideas, and expressing what they learn. In other words, a differentiated classroom provides different avenues to acquiring content , to processing or making sense of ideas, and to developing products so that each student can learn effectively.”

Tomlinson’s emphasis on “Content, Process and Product” is fundamental to the theory and practice of differentiated instruction.

History of Differentiated Instruction [From One-Room Schoolhouses to the 21st Century Classroom]

The one-room schoolhouses of centuries gone by are often mentioned when your research topic is “the history of differentiated instruction.” Though not called by that name, it was understood that teachers in the traditional one-room schoolhouse setting, out of necessity, had to develop strategies for teaching students of different ages, abilities, literacy levels and backgrounds.

“Today’s teachers still contend with the essential challenge of the teacher in the one-room schoolhouse: how to reach out effectively to students who span the spectrum of learning readiness, personal interests, and culturally shaped ways of seeing and speaking about and experiencing the world,” Tomlinson writes in another of her notable texts on the topic, “ The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners.”

The magazine Educational Leadership, established in 1943 by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD), devoted an entire issue to the theme “The Challenge of Individual Difference” in 1953.

It invites readers to revisit the lead article by Carleton W. Washburne, “Adjusting the Program to the Child.” The report also cites the influence of Frederic Burk in the 1910s and other educators in recognizing the value of developing strategies for helping students “progress according to their own abilities.”

Some educational historians also draw connections between the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, with its emphasis on helping disadvantaged students and improving individual outcomes in education, and some of the core principles of differentiated instruction.

Today, differentiated instruction is widely practiced as a progressive approach to education that endeavors to leverage the unique learning characteristics each student brings to the classroom to deliver a more effective education than a so-called “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Reading Rockets, the Library of Congress Literacy Award-winning advocacy organization, also cites Tomlinson’s influence in mapping out the basic tenets of differentiated instruction , which guide classroom teachers in differentiating three specific aspects of the educational experience, plus a fourth that encompasses and expands upon these three:

- Content – the knowledge, concepts and skills that students need to learn based on the curriculum

- Process – the activities in which the student engages to understand and make sense of the content

- Products – the ways students demonstrate what they have come to know, understand and be able to do

Learning environment is the fourth variable in the differentiated instruction equation. It refers to the climate, or the look and feel of a classroom — the physical space as well as the tone set by the teacher to establish an atmosphere of mutually supportive learning.

A classroom with a learning environment optimized for differentiated instruction is one that:

- Establishes a safe and positive environment for learning

- Allows for individual work preferences

- Includes spaces to work quietly and without distraction as well as spaces that invite student collaboration

- Provides materials that reflect a variety of cultures and home settings

- Establishes clear guidelines for independent work that matches individual needs

- Helps students understand that some learners need to move around to learn while others do better sitting quietly

To help gauge the most effective strategies for reaching each student and helping them learn and perform to the best of their unique abilities, teachers are also encouraged to consider students’ individual:

- Readiness — This refers not as much to a student’s academic ability as to their capacity to learn new material in a particular subject or topic. Since one way to ensure learning growth is to challenge students with tasks that require them to stretch their minds, an awareness of student readiness can help teachers adjust the degree of difficulty to provide an appropriate level of challenge.

- Interest — Different students show interest in different topics and activities (from football to fashion to food, you name it). The basic theory here is that teachers can motivate students to learn by showing them how subjects being taught connect with their particular interests.

- Learning profile — The ways that students learn best can be shaped by a variety of factors including their culture, the learning environment (working solo or collaboratively, sitting still or moving around, in a quiet atmosphere or while listening to music), and their innate learning style or styles (for example, is the student a visual, auditory or kinesthetic learner?).

A simplified example of connecting a student’s interest to the content of a particular learning goal or assignment is illustrated in an Education Week video narrated by teacher and author Larry Ferlazzo, who explains that differentiating instruction is really about getting to know your students and making decisions, often in the moment, based on what they need.

During a classroom assignment that involved an “argument essay” about what would be the worst natural disaster to experience, he noticed that one student had his head down on the desk and was not participating. Knowing that this student was interested in football, Ferlazzo engaged him to write his argument essay on the topic of “why his favorite team was the best.” In this case, the learning goal was developing the skills needed to make an effective argument (not learning about natural disasters) and the product was an essay that followed all the attributes of a good argument essay.

When it comes to process , the road to the best outcomes might involve teachers asking themselves: What are the learning objectives? And what are the best roads to get there for different students? A few of the possibilities include:

- Having students work alone or in groups

- Offering a choice on a variety of writing prompts

- Connecting subject matter to individual interests

- Employing tiered activities through which the whole class works on the same important subject matter and skills, but with different levels of support, challenge or complexity

Regarding product , Tomlinson has written, “students can propose the way they’d like to show us something, or we might offer them two choices — with the notion that they can make a deal with us to do the third one.”

Ferlazzo says that when he gave tests, he sometimes included an extra blank page for students to write (or write and draw!) “anything else they remember about the topic being tested that they think is important.” He found that sometimes those responses were more inspired than the responses to his test questions. Ferlazzo said his version of differentiated instruction did not require a significant amount of extra work, but “did require that I had relationships with my students to know their strengths, challenges and interests.”

Another example of a classroom that employs an interesting variation of differentiated instruction is seen in an Edutopia video titled “Station Rotation: Differentiating Instruction to Reach All Students.” At Highlander Charter School in Rhode Island, classes start with a group lesson then break into smaller groups, each of which rotates through three stations designed to connect students with the material using different learning modalities.

The biggest criticism around differentiated instruction often centers on the idea that it requires teachers to take on an even heavier workload. Here is a brief summary of some of the chief pros and cons.

- Research suggests that differentiated instruction can be effective both for students who are academic achievers as well as those with learning challenges or even significant disabilities.

- When offered more options on how they can learn the material, students become more motivated and engaged, taking on more responsibility for their own learning.

- When students are more engaged in learning, there are typically fewer classroom disciplinary problems.

- Many educators believe that making differentiated instruction truly worthwhile requires significant additional work devoted to lesson planning.

- Though differentiated instruction comes naturally to some educators, when practiced schoolwide there can be a significant learning curve and there are often insufficient professional development resources.

- Critics contend that there isn’t enough research to justify the additional resources required to support the benefits of differentiated instruction.

What is differentiated instruction?

Carol Ann Tomlinson, an author and teacher regarded as a pioneer in differentiated instruction, describes it as “a way of thinking about teaching which suggests that … we teach with an eye on the student.” She emphasizes four key pillars of differentiated instruction: Content, Process, Product and Learning Environment.

Does differentiated instruction require more work for teachers?

The amount of additional preparation required is open to debate, but most educators agree that successfully employing differentiated instruction does require building relationships with students to know their strengths, challenges and interests.

What are the biggest benefits of differentiated learning?

Advocates contend that by connecting subject matter and learning goals to individual student strengths, interests and learning styles, differentiated instruction can inspire students to be more engaged and motivated, thereby creating improved learning outcomes by inspiring them to take on more responsibility for their own learning.

Many teachers reach a point in their career where they want to further develop their skills to make an even greater impact in their classroom, often following a particular passion or specific area of interest such as differentiated instruction. Whatever one’s desired area of focus, there are a range of master’s degree programs — including online options — designed to help working teachers achieve their career development goals.

For example, the University of San Diego offers an online Master of Education degree program with different specializations ranging from Inclusive Learning to Curriculum and Instruction . The curriculum in both specializations includes coursework focused on “strategies that provide differentiated support for the success of all students.”

Differentiated instruction is a comprehensive approach to teaching whose essence, according to the educational advocate Ferlazzo, is this: “Recognizing that all of our students bring different gifts and challenges, and that as educators we need to recognize those differences and use our professional judgment to flexibly respond to them in our teaching.”

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Top 11 Reasons to get Your Master of Education Degree

Free 22-page Book

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Instruction

Differentiated Instruction

So far in this discussion, we have ignored the obvious variety among students. Yet their diversity is a reality that every teacher recognizes. Whatever goals and plans we make, some students learn the material sooner or better than others. For any given goal or objective, some students need more time than others in order to learn. And any particular teaching strategy will prove more effective with some students than others. Effective teaching requires differentiated instruction —providing different materials, arrangements, and strategies to different students. The differentiation can include unique structural arrangements in the school, such as special tutoring for individuals or special classes for small groups needing particular extra help. Differentiation can also include extra attention or coaching within a classroom for individual students or small groups (Tomlinson, 2006; Goddard, Goddard, & Tschannen-Moran, 2007).

Video 8.5.1. Differentiating Instruction: It’s Not as Hard as You Think provides an introduction to differentiation in instruction.

Differentiation is commonly used in “heterogeneous grouping”—an educational strategy in which students of different abilities, learning needs, and levels of academic achievement are grouped together. In heterogeneously grouped classrooms, for example, teachers vary instructional strategies and use more flexibly designed lessons to engage student interests and address distinct learning needs—all of which may vary from student to student. The basic idea is that the primary educational objectives—making sure all students master essential knowledge, concepts, and skills—remain the same for every student, but teachers may use different instructional methods to help students meet those expectations.

Teachers who employ differentiated instructional strategies will usually adjust the elements of a lesson from one group of students to another so that those who may need more time or a different teaching approach to grasp a concept get the specialized assistance they need, while those students who have already mastered a concept can be assigned a different learning activity or move on to a new concept or lesson.

In more diverse classrooms, teachers will tailor lessons to address the unique needs of special-education students, high-achieving students, and English-language learners, for example. Teachers also use strategies such as formative assessment —periodic, in-process evaluations of what students are learning or not learning—to determine the best instructional approaches or modifications needed for each student.

Differentiation techniques may also be based on specific student attributes, including interest (what subjects inspire students to learn), readiness (what students have learned and still need to learn), or learning style (the ways in which students tend to learn the material best)

Video 8.5.2. Differentiating Instruction: How to Plan Your Lessons provides suggestions for including differentiation in lesson planning.

The Debate on Equity

Differentiation plays into ongoing debates about equity and “academic tracking” in public schools. One major criticism of the approach is related to the relative complexities and difficulties entailed in teaching diverse types of students in a single classroom or educational setting. Since effective differentiation requires more sophisticated and highly specialized instructional methods, teachers typically need adequate training, mentoring, and professional development to ensure they are using differentiated instructional techniques appropriately and effectively.

Some teachers also argue that the practical realities of using differentiation—especially in larger classes comprising students with a wide range of skill levels, academic preparation, and learning needs—can be prohibitively difficult or even infeasible. Yet other educators argue that this criticism stems, at least in part, from a fundamental misunderstanding of the strategy. In her book How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms , the educator and writer Carol Ann Tomlinson, who is considered an authority on differentiation, points out a potential source of confusion, “Differentiated instruction is not the ‘Individualized Instruction’ of the 1970s.”

In other words, differentiation is the practice of varying instructional techniques in a classroom to effectively teach as many students as possible, but it does not entail the creation of di stinct courses of study for every student (i.e., individualized instruction). The conflation of “differentiated instruction” and “individualized instruction” has likely contributed to ongoing confusion and debates about differentiation, particularly given that the terms are widely and frequently used interchangeably (Myths and Misconceptions, n.d).

Differentiated Instruction and Implication for Universal Design for Learning

To differentiate instruction is to recognize students’ varying background knowledge, readiness, language, preferences in learning, and interests; and to react responsively. As Tomlinson notes in her recent book Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners (2014), teachers in a differentiated classroom begin with their current curriculum and engaging instruction. Then they ask, what will it take to alter or modify the curriculum and instruction so that each learner comes away with the knowledge, understanding, and skills necessary to take on the next important phase of learning. Differentiated instruction is a process of teaching and learning for students of differing abilities in the same class. Teachers, based on characteristics of their learners’ readiness, interest, and learning profile, may adapt or manipulate various elements of the curriculum (content, process, product, affect/environment). These are illustrated in the table below which presents the general principles of differentiation by showing the key elements of the concept and the relationships among those elements.

Table 8.5.1. Principles of differentiation by key elements

Adapted with permission from Carol Tomlinson: Differentiation Central Institutes on Academic Diversity in the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia (September 2014).

Identifying Components/Features

While Tomlinson and most recognize there is no magic or recipe for making a classroom differentiated, they have identified guiding principles, considered the “Pillars that Support Effective Differentiation”: Philosophy, Principles, and Practices. The premise of each is as follows:

The Philosophy of differentiation is based on the following tenets:

- recognizing diversity is normal and valuable,

- understanding every student has the capacity to learn,

- taking responsibility to guide and structure student success,

- championing every student entering the learning environment and assuring equity of access

The Principles identified that shape differentiation include

- creating an environment conducive to learning

- identifying a quality foundational curriculum

- informing teaching and learning with assessments

- designing instruction based on assessments collected

- creating and maintaining a flexible classroom

Teacher Practices are also essential to differentiation, highlighted as

- proactive planning to address student profiles

- modifying instructional approaches to meet student needs

- teaching up (students should be working just above their individual comfort levels)

- assigning respectful tasks responsive to student needs—challenging, engaging, purposeful

- applying flexible grouping strategies (e.g., stations, interest groups, orbital studies)

- Several elements and materials are used to support instructional content. These include acts, concepts, generalizations or principles, attitudes, and skills. The variation seen in a differentiated classroom is most frequently in the manner in which students gain access to important learning. Access to content is seen as key.

- Align tasks and objectives to learning goals. Designers of differentiated instruction view the alignment of tasks with instructional goals and objectives as essential. Goals are most frequently assessed by many state-level, high-stakes tests and frequently administered standardized measures. Objectives are frequently written in incremental steps resulting in a continuum of skills-building tasks. An objectives-driven menu makes it easier to find the next instructional step for learners entering at varying levels.

- Instruction is concept-focused and principle-driven. Instructional concepts should be broad-based, not focused on minute details or unlimited facts. Teachers must focus on the concepts, principles, and skills that students should learn. The content of instruction should address the same concepts with all students, but the degree of complexity should be adjusted to suit diverse learners.

- Clarify key concepts and generalizations. Ensure that all learners gain powerful understandings that can serve as the foundation for future learning. Teachers are encouraged to identify essential concepts and instructional foci to ensure that all learners comprehend.

- Flexible grouping is consistently used. Strategies for flexible grouping are essential. Learners are expected to interact and work together as they develop knowledge of new content. Teachers may conduct whole-class introductory discussions of content big ideas followed by small group or paired work. Student groups may be coached from within or by the teacher to support the completion of assigned tasks. Grouping of students is not fixed. As one of the foundations of differentiated instruction, grouping and regrouping must be a dynamic process, changing with the content, project, and ongoing evaluations.

- Classroom management benefits students and teachers. To effectively operate a classroom using differentiated instruction, teachers must carefully select organization and instructional delivery strategies. In her text, How to Differentiate Instruction in Mixed-Ability Classrooms (2001), Carol Tomlinson identifies 17 key strategies for teachers to successfully meet the challenge of designing and managing differentiated instruction.

- Emphasize critical and creative thinking as a goal in lesson design. The tasks, activities, and procedures for students should require that they understand and apply meaning. Instruction may require support, additional motivation; and varied tasks, materials, or equipment for different students in the classroom.

- Initial and ongoing assessment of student readiness and growth are essential. Meaningful pre-assessment naturally leads to functional and successful differentiation. Incorporating pre- and ongoing assessment informs teachers so that they can better provide a menu of approaches, choices, and scaffolds for the varying needs, interests, and abilities that exist in classrooms of diverse students. Assessments may be formal or informal, including interviews, surveys, performance assessments, and more formal evaluation procedures.

- Use assessment as a teaching tool to extend rather than merely measure instruction. Assessment should occur before, during, and following the instructional episode; and it should be used to help pose questions regarding student needs and optimal learning.

- Students are active and responsible explorers. Teachers respect that each task put before the learner will be interesting, engaging, and accessible to essential understanding and skills. Each child should feel challenged most of the time.

- Vary expectations and requirements for student responses. Items to which students respond may be differentiated so that different students are able to demonstrate or express their knowledge and understanding in a variety of ways. A well-designed student product allows varied means of expression and alternative procedures and offers varying degrees of difficulty, types of evaluation, and scoring.

Affect/Environment

- Developing a learning environment. Establish classroom conditions that set the tone and expectations for learning. Provide tasks that are challenging, interesting, and worthwhile to students.

- Engaging all learners is essential. Teachers are encouraged to strive for the development of lessons that are engaging and motivating for a diverse class of students. Vary tasks within instruction as well as across students. In other words, an entire session for students should not consist of all lecture, discussion, practice, or any single structure or activity.

- Provide a balance between teacher-assigned and student-selected tasks. A balanced working structure is optimal in a differentiated classroom. Based on pre-assessment information, the balance will vary from class to class as well as lesson to lesson. Teachers should ensure that students have choices in their learning.

The following instructional approach to teaching mathematics patterns has several UDL features (see Table 8.5.2). Through the use of clearly stated goals and the implementation of flexible working groups with varying levels of challenge, this lesson helps to break down instructional barriers . We have identified additional ways to reduce barriers in this lesson even further by employing the principles of UDL teaching methods and differentiated instruction. We provide recommendations for employing teaching methods of UDL to support this lesson in Table 8.5.3. Note that we are not making generalized recommendations for making this lesson more UDL, but instead are focusing on ways that differentiated instruction, specifically, can help achieve this goal.

Table 8.5.2. UDL elements in a differentiated instruction mathematics lesson

Table 8.5.3. UDL strategies to further minimize lesson barriers in a differentiated instruction lesson plan for mathematics

Training in Differentiated Instruction

The IRIS Center of Peabody College, Vanderbilt University provides a training module for those that wish to learn more about Differentiated instruction: Maximizing the learning of all students.

Candela Citations

- Differentiated Instruction. Authored by : Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose. Provided by : Hudson Valley Community College. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/edpsy/chapter/differentiated-instruction/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. Provided by : The Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/educationalpsychology. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Instructional Methods, Strategies and Technologies to Meet the Needs of All Learners . Authored by : Paula Lombardi. Retrieved from : https://granite.pressbooks.pub/teachingdiverselearners/chapter/differentiated-instruction-2/. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Differentiating Instruction: Itu2019s Not as Hard as You Think. Provided by : Education Week. Retrieved from : https://youtu.be/h7-D3gi2lL8. License : All Rights Reserved

- Differentiating Instruction: How to Plan Your Lessons. Provided by : Education Week. Retrieved from : https://youtu.be/rumHfC1XQtc. License : All Rights Reserved

Educational Psychology Copyright © 2020 by Nicole Arduini-Van Hoose is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Foundational Guide to Differentiated Instruction

- Classroom Activities/Strategies/Guides

Most of us have experienced the frustration of one-size-fits-all clothing at some point. The concept or idea isn’t necessarily bad, but it just doesn’t work for everyone. The same can be said of education. Educators know that education does not work well as a one-size-fits-all approach. The more students in a classroom, the more diverse classrooms become. And with classrooms becoming increasingly diverse, the need for differentiated instruction becomes more critical.

Differentiated instruction is an approach to teaching that recognizes the diverse needs and abilities of students. Rather than offering a one-size-fits-all approach that forces students to fit into a predetermined box, instruction should meet the individual, unique needs of the students. Differentiated instruction is extremely important because of its ability to foster equity and inclusion, create a more engaging and effective learning environment, and improve overall student achievement.

Ultimately, differentiated classrooms recognize students have diverse backgrounds, strengths, interests, and challenges, and a one-size-fits-all approach to instruction may not be effective for all learners. While differentiated instruction and its strategies may pose some challenges, the benefits of differentiation in the classroom are numerous and the challenges can be overcome.

Strategies for Implementing Differentiated Instruction

Simply put, differentiated strategies involve tailoring instruction to meet the diverse needs of all learners. This tailoring can be something as easy as identifying the learning styles of students or can involve some intentional structuring of assignments. The goal isn’t to put more work on teachers and make them feel they need to edit or recreate every assignment. Instead, the goal is to give teachers the freedom to make adjustments to their ideas and curriculum that will lean into students’ strengths and therefore increase student achievement.

Identifying Learning Styles and Preferences