- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 October 2020

Ethics and the marketing authorization of pharmaceuticals: what happens to ethical issues discovered post-trial and pre-marketing authorization?

- Rosemarie D. L. C. Bernabe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4999-3117 1 , 2 ,

- Ghislaine J. M. W. van Thiel 3 ,

- Nancy S. Breekveldt 4 ,

- Christine C. Gispen 4 &

- Johannes J. M. van Delden 3

BMC Medical Ethics volume 21 , Article number: 103 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2725 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

In the EU, clinical assessors, rapporteurs and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use are obliged to assess the ethical aspects of a clinical development program and include major ethical flaws in the marketing authorization deliberation processes. To this date, we know very little about the manner that these regulators put this obligation into action. In this paper, we intend to look into the manner and the extent that ethical issues discovered during inspection have reached the deliberation processes.

To gather data, we used the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board database and first searched for the inspections, and their accompanying site inspection reports and integrated inspection reports, related to central marketing authorization applications (henceforth, application/s) of drugs submitted to the European Medicines Agency (EMA) from 2011 to 2015. We then extracted inspection findings that were purely of ethical nature, i.e., those that did not affect the benefit/risk balance of the study (issues related to informed consent, research ethics committees, and respect for persons). Only findings graded at least major by the inspectorate were included. Lastly, to identify how many of the ethically relevant findings (ERFs) reach the application deliberation processes, we extracted the relevant joint response assessment reports and reviewed the sections that discussed inspection findings.

From 2011 to 2015, there were 390 processed applications, of which 65 had inspection reports and integrated inspection reports accessible via the database of the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. Of the 65, we found ERFs in 37 (56.9%). The majority of the ERFs were graded as major and half of the time it was informed-consent related. A third of these findings were related to research ethics committee processes and requirements. Of the 37 inspections with ERFs, 30 were endorsed in the integrated inspection reports as generally GCP compliant. Day 150 joint response assessment reports and Day 180 list of outstanding issues were reviewed for all 37 inspections, and none of the ERFs were carried over in any of the assessment reports or list of outstanding issues.

None of the ethically relevant findings, all of which were graded as major or critical in integrated inspection reports, were explicitly carried over to the joint assessment reports. This calls for more transparency in EMA application deliberations on how ERFs are considered, if at all, in the decision-making processes.

Peer Review reports

Several documents from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) speak of the place of ethics in the regulatory processes involved in a marketing authorization application (henceforth, application) [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. One of these is the document, Points to consider on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) inspection findings and the benefit-risk balance where the mandate of regulators in terms of the place of these ethical issues in the evaluation process is explained as follows:

GCP inspection findings – even if not directly influencing the benefit-risk balance —will still be important if they raise serious questions about the rights, safety and well-being of trial subjects and hence the overall ethical conduct of the study. It is an obligation of clinical assessors, rapporteurs and the CHMP also to assess the ethics of a clinical development programme, and major ethical flaws should have an impact on the final conclusions about approvability of an application. Consequently, ethical misconduct could result in rejection of the application [ 4 ]. ( italics mine ).

In a previous publication, we identified the types of ethical issues that pharmaceutical regulators encounter post-marketing through inspection reports [ 5 ]. In this publication, we discovered that based on 2008–2012 inspection reports comprising of 112 medicinal products and 288 clinical trial sites, inspectors frequently and regularly encounter ethically relevant findings (ERFs). Specifically, "At least major ERFs were present in almost all medicinal products with ERFs. The categories with the highest number of ERFs were protocol issues, patient safety, and professionalism issues." Also, "on average, there were 7.54 major and 2.95 critical ERFs per medicinal product application, although ERFs can increase to 30 major and 12 critical" [ 5 ]. For more information on what inspectors consider as major and critical ERFs, the reader is directed to consult our article entitled, “Ethics in clinical trial regulation: ethically relevant issues from EMA inspection reports” [ 5 ]. Though it is fair to assume that at least some of the ERFs that “directly influence the benefit-risk balance” of an investigational medicinal product submitted for marketing authorization application would be carried over to the succeeding regulatory deliberation processes, we cannot make the same assumption about GCP inspection findings that do “not directly influence the benefit-risk balance.” The latter remains unknown and, as such, we know very little about the manner that “clinical assessors, rapporteurs and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP)” fulfill this obligation of “assessing the ethics of a clinical development programme.” To respond to this need, it is the goal of this article to look into the manner and extent that ethical issues that do not affect benefit-risk balanced and were discovered during inspection have reached the deliberation processes, i.e., how “major ethical flaws” have impacted “the final conclusions about (the) approvability of an application.”

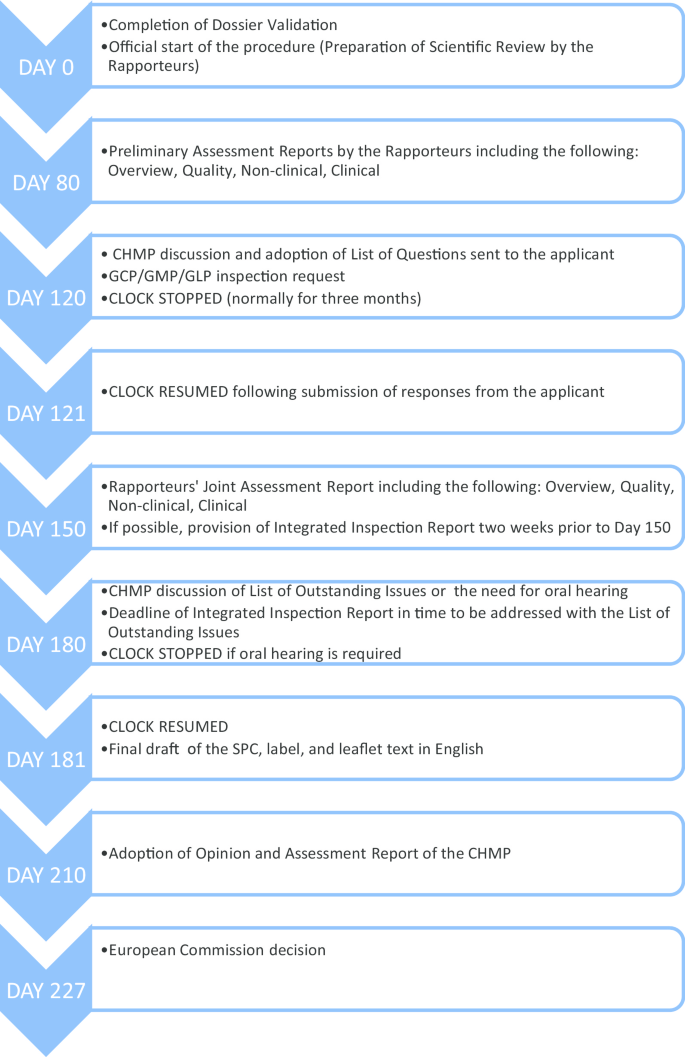

Before we elaborate on our methodology, it is imperative that we quickly go through the European centralized procedure for authorizing medicinal products, which we have outlined in Fig. 1 .

European centralized procedure for authorizing medicinal products [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]

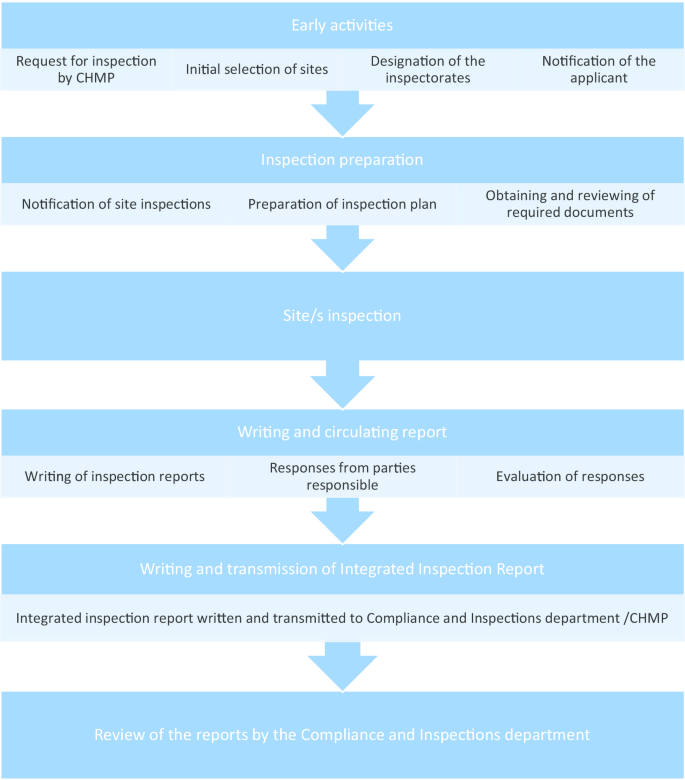

As can be seen from Fig. 1 , the request for GCP inspections and the eventual circulation of the integrated inspection report to the CHMP happens between Day 120 and Day 180. All inspection reports and integrated inspection reports are submitted to the CHMP for the latter’s consideration. Figure 2 provides the details leading to the circulation of the integrated inspection report.

Process of inspection activities related to CHMP request [ 2 , 3 ]

Given the centralized procedure outlined above, to understand the extent to which ethical issues have reached the application deliberation processes, we searched for inspection reports, integrated inspection reports, Day 150 joint assessment reports, and Day 180 List of Outstanding Issues .

To gather data, we used the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board database and first searched for inspections, and their accompanying site inspection reports and integrated inspection reports, related to central application of drugs submitted to the EMA from 2011 to 2015. For the list of drugs processed for central marketing authorization, we used the European public assessments report database [ 9 ].

Inspection findings include both scientific and ethical issues. To determine which issues to extract, we used the following system. In another publication, we extracted the ethical issues from GCP inspection reports and came up with the following classifications of ethical issues: informed consent, monitoring and oversight, patient safety, professionalism and or qualification issues, protocol compliance or protocol issues, research ethics committees, and respect for persons [ 5 ]. It can be observed that the issues in some of the classifications can both be scientific and ethical. An ethical issue can also be a scientific issue when it could affect the benefit-risk balance of a scientific evaluation of an application [ 4 ]. The following classifications have this dual characteristic: monitoring and oversight, patient safety, professionalism and or qualification issues, protocol compliance or protocol issues. Since we wish to investigate the impact of an ethical issue that is not a scientific issue, we shall look at the issues under the following classifications only: informed consent, research ethics committees, and respect for persons. The former three classifications coincide with the list of ethical issues that may trigger a “for cause” inspection as stated in the document, Points to consider for assessors, inspectors and EMA inspection coordinators [ 1 ]. We used another of our publications [ 10 ] to define the scope of informed consent ( IC ), research ethics committees ( REC ), and respect for persons.

Even within the latter three categories, since we are testing how far purely ethical issues identified in inspections reach the evaluation processes, we excluded inspection findings that may influence the benefit-risk balance evaluation. For example, one of the issues identified as likely to influence benefit-risk evaluation is “inadequate reporting of adverse events and other safety endpoints.” If we look at the definition of respect for persons, patient safety is an aspect of its definition and inadequate reporting of (severe) adverse events a concrete example. Because this finding is likely to affect benefit-risk evaluation, i.e., it is clearly both a scientific and an ethical issue, it was excluded from our analysis.

The GCP deviation findings from inspection reports that were graded by the inspectors as either major or critical and that may be categorized under IC, REC, and/or respect for persons were extracted (henceforth ethically relevant findings, ERFs ). We used the integrated inspection reports to validate if the inspection findings still hold after the evaluation of the responses of the responsible parties on the initial inspection reports (see Fig. 2 ) and if the gravity rating remains the same. In case of a discrepancy, we followed the integrated inspection reports. The conclusion from the integrated inspection reports were extracted.

Next, to identify how many ERFs reach the evaluation of the application, the relevant joint response assessment reports (specifically the documents “overview” and “clinical”) and the list of outstanding issues (see Fig. 1 ) were extracted. We reviewed the sections where these assessment reports discussed the inspection findings and identified if and how these ERFs were considered in the evaluation processes and how the issues ultimately affected the decision on the application.

To avoid privacy and confidentiality issues, the results are on an aggregated format.

From 2011 to 2015, 390 applications were processed, of which 65 had inspection reports and integrated inspection reports accessible via the database of the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. Of the 65, we found ERFs in 37 (56.9%). These findings are summarized in Table 1 .

As can be seen from Table 1 , the majority of the ERFs were graded as major and half of the time it was IC-related. A third of these findings were related to research ethics committee processes and requirements.

Of the 37 inspections with ERFs, 30 were endorsed in the integrated inspection reports as generally GCP compliant. Table 2 presents the mean, mode, minimum, and maximum ERF values in all inspections, endorsed inspections (the 30 inspections), and not-fully-endorsed inspections (the remaining 7 inspections).

From Table 2 , we see that there is a difference in terms of the average number of ERFs and the maximum number of ERFs per inspection between the endorsed and the non-endorsed inspections. Non-endorsed inspections have higher values on both counts than endorsed inspections in terms of total number of ERFs, major ERFs, and critical ERFs. This means that the non-endorsed inspections have more and graver ERFs than the endorsed inspections.

In all the 30 endorsed inspections, the gravity ratings were retained and the corrective and preventive action (CAPA) proposals of the sponsors and investigators to address the ERFs were accepted by the inspectors. Note that CAPAs would in most instances be preventive, i.e., changes can be made only for future trials. Seven of the inspections were not fully endorsed as GCP compliant, partly due to ERFs.

Of the seven not-fully-endorsed inspection cases, three were declared non-GCP compliant with the consequence that (part of) the data were not endorsed for use for the assessment of an application. One was declared non-GCP compliant but data were still endorsed for use during assessment. In three cases, data were endorsed for use for assessment, but the inspectors expressed lingering concerns about ERFs and required a better approach from the sponsor in the future.

Day 150 joint response assessment reports and Day 180 list of outstanding issues were reviewed for all 37 inspections, and none of the ERFs were carried over in any of the assessment reports or list of outstanding issues. Table 3 summarizes these results.

In our study, we wanted to see how many of the ethical issues that were not likely to affect the scientific validity of the study and that were discovered during inspection have reached the evaluation processes for centralized applications of drugs. We did this by investigating how many of the ERFs from integrated inspection reports were reflected in Day 150 and Day 180 joint assessment reports. Our results are straightforward: of the 77 ERFs found in 56.9% of all inspections from 2011–2015, none of the ERFs were factored in, i.e., none of them were mentioned at all as factors to consider in either Day 150 joint response assessment reports or Day 180 list of outstanding issues. This means that though these ERFs may have been discussed internally, none of these were explicitly carried over to the joint assessment reports. Whether or not the inspections were endorsed was not a factor in the uptake of ERFs in Day 150 and Day 180 assessments. This is disturbing especially for the seven inspections where the inspectors did not guarantee general GCP compliance of the trial sites, three of which lingering concerns about ERFs were expressed by the inspectors. Overall, and based on inspection and assessment reports, this means that the mandate obliging clinical assessors, rapporteurs and the CHMP to also “assess the ethics of a clinical development programme, and major ethical flaws should have an impact on the final conclusions about approvability of an application” [ 1 ] have yet to be actualized or at least seen as factors explicitly considered during the assessment of an application. With that said, some considerations are worth mentioning.

First, it is unclear what standards inspectors use to declare that the inspected sites were generally GCP compliant in spite of major/critical ERFs. Major/critical issues are defined as “conditions, practices or processes that might adversely/adversely affect the rights, safety or well-being of the subjects and/or the quality and integrity of data” [ 11 ]. If major/critical ERFs at the very least have the possibility of affecting the rights, safety, or well-being of the subjects, how were these weighed and factored in the conclusion that the sites were generally GCP compliant? At the time of writing, we know of no EMA document that speaks about this process. Thus, there is a need for a transparent structure on grading standards as well as guidelines on the place of minor/major/critical findings in application decision-making.

Second, though the grading of critical/major/minor is used by the inspectors, it is not clear in EMA documents if the assessors should use the same grading system. Whether inspectors and assessors should and in fact use the same grading system is an area for future research.

Third, ERFs are best addressed early, and not during application deliberations when “damage” has already been done. This may mean encouraging preventive measures at the design stage of clinical trials, widening the capacity of research ethics committees to monitor approved clinical trials, reviewing sponsor responsibility in actively pursuing ethically compliant trials, and/or more active collaboration between RECs and drug regulators in terms of approving and monitoring clinical trials, among others.

Fourth, inspection reports provide a lot of insight on ethical and scientific matters such as the ethical acceptability of the elements of a pharmaceutical clinical trial which eventually becomes a basis for an application, integrity of the clinical trial data based on which pharmaceutical products are provided marketing authorization, among others. This should be sufficient reason for drug regulatory agencies to make them more accessible, if not public. This is a concern that was earlier made by Dal-Re, Kesselheim, and Bourgeois [ 12 ] in an opinion piece calling for the publication of inspection reports by drug regulatory bodies. Dal-re and colleagues correctly point out that doing so is part of these regulatory bodies’ public health mandate. It also allows for (a) individual assessment of “trial quality in publication decisions”; (b) provides more inputs for systematic reviews; and (c) provide means for clinical trial sponsors to correct mistakes and ensure participant safety [ 12 ].

Fifth, we saw above the EMA position that GCP issues, even those that do not affect the benefit-risk balance so long as these issues raise “serious questions about the rights, safety, and well-being of trial subjects” should have an “impact on the final conclusions about approvability of an application” [ 4 ]. In our study, we found that this is not (yet) the case. Unfortunately, we found no EMA document that elaborates on how ethical issues should affect application evaluation processes and no other publication to our knowledge engaged these issues, except ours. In an earlier publication [ 13 ], we proposed a 4-step procedure in evaluating ERFs, with sanctions depending on the evaluation of the gravity and magnitude of the ERF. However, it still remains to be seen how ERFs that do not affect the risk–benefit balance of an application such as the ones we dealt with in this manuscript should be evaluated by assessors and how such an assessment should impact the assessment process. This is work for future research.

None of the ethically relevant findings, all of which were graded as major or critical in integrated inspection reports, were explicitly carried over to the joint assessment reports. This means that from the vantage of these joint assessment reports , none of the ethically relevant findings seemed to have reached or impacted the application deliberation processes. This calls for more transparency in EMA application deliberations, specifically on how ERFs are considered in the decision-making processes.

Availability of data and material

The inspection reports, integrated inspection reports, Day 150, and Day 180 data that support the findings of this study are available from the database of the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB). Because of the sensitivity of the sources, the data may only be accessed with the permission of the MEB or similar European regulatory body.

Abbreviations

Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use

Corrective and preventive action

Ethically relevant findings

European Medicines Agency

Good Clinical Practice

Informed consent

Research ethics committees

European Medicines Agency. Points to consider for assessors, inspectors and EMA inspection coordinators on the identification of triggers for the selection of applications for “routine” and/or “for cause” inspections, their investigation and scope of such inspections. 2013. No description about the ethical conduct of the study (e.g. inclusion of vulnerable patients, high.

EMA. Procedure for reporting of GCP inspections requested by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). 2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2009/10/WC500004479.pdf .

European Medicines Agency. Procedure for coordinating GCP inspections requested by the CHMP. 2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2009/10/WC500004446.pdf .

European Medicines Agency. Points to consider on GCP inspection findings and the benefit-risk balance. 2012. https://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2013/01/WC500137945.pdf .

Bernabe RDLC, van Thiel GJMW, Breekveldt NS, Gispen-de Wied CC, van Delden JJM. Ethics in clinical trial regulation: ethically relevant issues from EMA inspection reports. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):637–45.

Article Google Scholar

Tobin JJ, Walsh G. Medical product regulatory affairs: pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, medical devices. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2008.

Book Google Scholar

European Commission. Authorisation procedures—the centralised procedure. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/what-we-do/authorisation-medicines#centralised-authorisation-procedure-section .

Schneider CK, Schäffner-Dallmann G. Typical pitfalls in applications for marketing authorization of biotechnological products in Europe. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:893–9.

EMA. European public assessment reports: background and context, 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/what-we-publish-when/european-public-assessment-reports-background-context .

Bernabe RDLC, Van Thiel GJMW, Van Delden JJM. What do international ethics guidelines say in terms of the scope of medical research ethics? BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17:23.

EMA. Classification and analysis of the GCP inspection findings of GCP inspections conducted at the request of the CHMP. 2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2014/12/WC500178525.pdf .

Dal-Ré R, Kesselheim AS, Bourgeois FT. Increasing access to FDA Inspection reports on irregularities and misconduct in clinical trials. J Am Med Assoc: JAMA. 2020;19:1903–4.

Bernabe RDLC, van Thiel GJMW, Breekveldt NS, Gispen CC, van Delden JJM. Regulatory sanctions for ethically relevant GCP violations. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24:2116–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The views expressed by the authors are their personal views and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board.

This project was funded by the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, University of South-Eastern Norway, Kongsberg, Norway

Rosemarie D. L. C. Bernabe

Centre for Medical Ethics, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Ghislaine J. M. W. van Thiel & Johannes J. M. van Delden

Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Nancy S. Breekveldt & Christine C. Gispen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RDLCB downloaded the data, processed, and interpreted the data. She wrote all the drafts as well. GJMWT, NSB, CCG, and JJMD discussed the interpretation results and contributed to the various drafts. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosemarie D. L. C. Bernabe .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval was waived according to Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RDLC Bernabe received funds from the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board for this project. CC Gispen and NS Breekveldt worked/works for the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board. GJMW van Thiel and JJM van Delden have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bernabe, R.D.L.C., van Thiel, G.J.M.W., Breekveldt, N.S. et al. Ethics and the marketing authorization of pharmaceuticals: what happens to ethical issues discovered post-trial and pre-marketing authorization?. BMC Med Ethics 21 , 103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00543-w

Download citation

Received : 24 April 2019

Accepted : 13 October 2020

Published : 27 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00543-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Medical Ethics

ISSN: 1472-6939

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 30 January 2019

Pharmaceutical marketing strategies’ influence on physicians' prescribing pattern in Lebanon: ethics, gifts, and samples

- Micheline Khazzaka ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9764-7243 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 19 , Article number: 80 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

47k Accesses

35 Citations

68 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drug companies rely on their marketing activities to influence physicians. Previous studies showed that pharmaceutical companies succeeded to manage physicians prescribing behavior in developed countries. However, very little studies investigated the impact of pharmaceutical marketing strategies on prescribing pattern in developing countries, middle-eastern countries. The objective of this research was to examine the influence of drug companies’ strategies on physicians’ prescription behavior in the Lebanese market concerning physicians’ demographic variables quantitatively. Moreover, this study tested whether Lebanese physicians considered gifts and samples acceptance as an ethical practice.

Sampling was done by using a non-probability method. An online cross-sectional study was conducted through WhatsApp. A self-administered questionnaire survey was conducted during the months of February and March 2018. Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient was calculated. Data were statistically analyzed by using IBM SPSS statistics version 24 software. Chi-square and Cramer’s v tests were used to finding sign correlation, and Spearman test was used to measure the strength and direction of a relationship between variables.

Results found that pharmaceutical marketing strategies are correlated to physicians’ prescribing behavior. We demonstrated that the majority of the promotional tools tested were mostly or sometimes motivating physicians to prescribe promoted drugs. The major tools that physicians agreed to be mostly motivated by are visits of medical representatives and drug samples while sales calls made by pharmaceutical companies are the less influential tool. Regarding gift acceptance, this study demonstrated that physicians consider gifts’ acceptance as a non-ethical practice. Results showed that most physicians use free samples to treat their patients.

We demonstrated that there is a relationship between physicians’ prescribing pattern and their age, gender and the location of practice.

Conclusions

Findings of this study provided an insightful work, serving as one of the first humble steps in the imminent direction of merging this paper with the previous literature. From a managerial perspective, pharmaceutical marketing managers of drug companies can use the research findings to design better their strategies directed to the Lebanese physicians who can also benefit from the results obtained.

Peer Review reports

Pharmaceutical marketing efforts directed to physicians are getting more and more attention over the years. There are many tactics adopted by pharmaceutical companies [ 1 ] such as physicians-targeted promotions which are free samples, journal advertisements [ 2 ], printed product literature and other gifts that helped them to increase the acceptability of their products [ 3 ]. On average, pharmaceutical companies spent 20% or more of their sales on marketing [ 4 ] which made them a lot of money, and they had little incentive to stop those tactics [ 5 ]. It was estimated that 84% of pharmaceutical marketing efforts are directed toward physicians [ 2 ] because from the manufacturer’s point of view, physicians are the key decision makers [ 6 , 7 , 8 ], the gatekeepers to drug sales [ 9 ]. The structure of pharmaceutical markets differs from country to country because it has a national character. However, the pharmaceutical industry has an international nature [ 4 ]. To the best of our knowledge, few published studies addressed the situation in the developing world, and very few were those in the middle-eastern countries.

In Lebanon, inappropriate prescribing practices for certain prescription drugs are a common problem. One study found that 40% of all prescriptions in seven hospitals in Lebanon contained an error, of which 9% were unnecessary medication prescription [ 10 ]. One of the explanations to this observation might be because of physician-targeted promotions [ 2 ] adopted by pharmaceutical companies to increase the acceptability of their products [ 3 ].

Although many articles contemplated various theories of marketing influence on physicians, there is still a gap to fill. Ethical acceptability of gifts and samples is a comparatively new topic drawing momentous attention. Given the interdisciplinary nature of this research, it was appropriate for us to consider relevant theories from some different disciplines: diffusion and adoption theory, advertising theory, agency theory and role theory that influence the individual and the environment in which new products are adopted (drugs prescribed). Therefore, this study covered physicians’ opinion regarding the ethical acceptability of gifts and samples and highlighted physicians’ profile and demographic parameters influencing their prescribing behavior.

This desk research was an outcome of the authors’ academic and professional interest in the subject of pharmaceutical marketing and its impact on physicians’ prescribing pattern, especially in the mentioned country.

From an academic view, this present study aimed to add knowledge to the existing literature. It was an aggregate account of the connected exploration across disciplines with practical connotations.

Therefore, this investigation subtly attempted to bring substantial academic and managerial implications.

Academically, in searching existing literature, the present study identified some gaps. The majority of researches conducted were in developed countries. Developing countries received quite a bit of attention.

Therefore, a study of drug companies’ impact on Lebanese physicians prescribing behavior would report an original empirical research and would inform practice and future research by providing an insight into which extent pharmaceutical marketing strategies influenced Lebanese physicians prescribing behavior and what was the most influential strategy. No scholarly article merged in one study pharmaceutical marketing strategies in Lebanon, their impact on physicians prescribing pattern and physicians opinion regarding ethical acceptability of gifts and samples to find the correlation between them. This paper was virtually the first to advocate such a reform, and it served as one of the first humble steps in the imminent direction of merging this paper with the previous literature.

From a managerial perspective, a good understanding of drug companies influence on physicians provided pharmaceutical managers a framework to optimize promotion activities by firstly deciding where to focus their efforts to increase their benefits and secondly by choosing the best promotional approach and tool to persuade physicians best and thus avoiding any wasteful expenditure [ 8 ]. Additionally, the observance of ethical theories for medicinal drug promotion by doctors contributed to a more rational prescription of drugs. From another hand, when drug companies had more influence on some physicians and not on others, companies’ managers began to address the question regarding physicians opinion about the ethicality of receiving gifts and samples as a factor preventing these doctors from being influenced. If there was a difference in physicians’ opinion, managers then began to address possible reasons for the differences in answers observed such as demographic factors and physicians’ profile (location of practice, age or year of graduation and its influence on rates of adoption, gender, and nature of practice).

Conducting such a scholarly study from a managerial perspective aimed at highlighting functional implications and future research possibilities was of equal interest to academia and professionals.

The primary focus of the pharmaceutical industry was on profitability [ 11 ]. Thus, it was trying to leave a lasting impression on the prescribers (physicians) mind [ 12 ]. Normative principles of justice and fidelity required that physicians stay free from outside influence with regards to decisions about patient care [ 11 ].

Thus, it would be helpful for both, physicians and pharmaceutical industries to be aware of ethical theories and ethical principles [ 13 ]. The four fundamental ethical theories that are among the most frequently discussed in the business ethics literature are egoism [ 14 ], utilitarianism, deontology [ 15 ], and social justice.

The application of ethical theories during interaction with the pharmaceutical industry

The purpose of these theories was to help doctors and pharmaceutical companies’ managers acquire insight into their beliefs about the many criticisms that were made against marketing and, especially, insight about where they stood on the morally difficult situations that confronted them and what actions they would take in response to them. In practical ethics, two concepts existed while making decisions: utilitarian and deontological. In utilitarian ethics, consequences justified the ways to achieve it, but in deontological ethics, duties were of significant importance and outcomes may not justify the means [ 13 ].

Pharmaceutical marketing personalized to physicians such as the provision of samples and gifts raised such ethical issues [ 16 ]. To make effective decisions, the key was to think about different choices regarding their ability to accomplish one of the physicians’ most important goals that were ethical prescribing of drugs. Five ethical principles were identified as the cornerstone of the ethical guidelines [ 17 ], they helped to explain and to clarify the issues involved in a specific dilemma, and they were globally valuable to approach ethical and appropriate decision-making: beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, justice, and fidelity [ 18 ].

Marketing and promotion practices regarding the Lebanese code of ethics

In Lebanon, in 2016, the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health undertook the initiative to stipulate a Code of Ethics in partnership with the concerned parties to set regulatory frameworks. These frameworks ensured respect of legal, ethical, and scientific principles in the medicinal market as well as enhancing the rational use of drugs to prevent practices that do not comply with ethics by acting as a reliable reference to marketing practices. It was established in accordance with the Lebanese cultural context leading to the particular need for this research in Lebanon since no well-documented studies were done previously. The Lebanese Code of Ethics was divided into three main components which are: Marketing and Promotion Practices, Implementation Procedures, and the Pledge and signature [ 19 ].

While we were concerned with the process of prescription (adoption of drugs), we must also take into account many reasons why prescribing a specific medication may be unaccepted by some physicians and not by others [ 20 , 21 ]. Variables such as the degree of socialization, proximity to peers, rural vs. urban local of practice, do exist between product message and the act of prescribing.

Research by Tamblyn, McLeod, Hanley, Girard, and Hurley (2003) [ 22 ] indicated that new drug utilization was lower among generalists and specialists practicing in rural. In consideration of the influence of age, sociologists, psychologists, and marketers did much to document the resistance to change common among the elderly [ 23 ]. The combined observations from the literature were best summarized with the recognition that the older the consumer, the more negative the view toward technology, and the lower the use of various technologies (including new prescription drugs).

While there was very little in the literature that considered the influence of gender on prescribing, there were also relatively few studies that were conducted in the area of customer (physicians) behavior on gender differences [ 24 ]. A review of the consumer behavior literature [ 25 , 26 ], identified men as being more independent, confident, competitive, extremely motivated and more willing to take risks. The results of Inman and Pearce (1993) [ 27 ] suggested that female gender was strongly associated with the likelihood of not prescribing, or prescribing less than their male colleagues.

Adoption and diffusion theory

Physician prescribing pattern is a very wide concept including various dimensions. In this research, the focus was on the adoption of drugs. The process of adoption often was referred to as the process of diffusion by which new ideas and products became adopted by society [ 28 ]. An undeniable fact is that marketing efforts have a significant impact on physicians’ decision to adopt [ 29 ] and can initiate the process of diffusion [ 30 ].

Advertising theory

One of the main purposes of advertising was to entice the consumer to purchase the product [ 31 ], that was to prescribe as this is ultimately the metric against which pharmaceutical manufacturers measure success or failure.

Regardless of the role the physician occupied, in an environment in which the chooser is not the user, he is still the target of extensive pharmaceutical marketing within the context of advertising theory [ 32 ]. Therefore, the focus of this study was mainly on pharmaceutical marketing strategies as a factor influencing doctors’ decision. In their role as consumers, physicians created and store a set of preferred brands against which they simplify routine decision making.

In their role as consumers, physicians created and store a set of preferred brands against which they simplify routine decision making [ 33 ].

Agency theory

Agency theory served this research well, as in an agency relationship, the principal delegates the decision-making authority to an agent to perform some action on the principal’s behalf [ 34 ].

In the context of the above definition, the manufacturer as principal depended on the physician as the agent to select drugs from their specific offering. The patient, in their role as principal, depended on the physician, acting as the agent, to choose or prescribe the appropriate drug. Saying that the theory of planned behavior [ 35 ] was primordial to understand physicians’ behavior as it relates to prescribing, and oft considering when attempting to modify or influence physician prescribing [ 36 ].

Role theory

It served as a link between agency theory and the theory of planned behavior. It considered the foundations of the theory of planned behavior which are based upon an individual’s attitude toward the behavior, a perceived behavioral control and subjective norms [ 35 ] and agency theory, which focused on principal-agent relationships [ 37 ]. In this predefined context, role theory thus permitted better management/understanding of the dynamic aspects of the provider-client (agent-principal/physician-manufacturer) interface and centers on role performance and the interpersonal dimensions of service quality [ 38 ].

Physicians as customers and relationship marketing theory

Pharmaceutical sales and pharmaceutical marketing analysts realized that the success of a brand depended mostly on the prescribing behavior (change to another brand) of the physician [ 39 ] who is the most crucial target customer for the pharmaceutical enterprises.

To remain profitable, monitoring the prescribing practice of each physician needed a suitable and successful relationship marketing program. The overall purpose of relationship marketing was to improve marketing productivity and enhance mutual value for the parties involved in the relationship. Consequently, instead of manipulating the customers (physicians) they were involved in the relationship [ 40 ].

As shown in Table 1 above, very few studies covered and studied the impact of pharmaceutical marketing strategies on the prescribing behavior of physicians in the developing countries of the middle-east. A report was published in “executive magazine” in 2015 by El-Jardali and Fadlallah [ 10 ] where it was found that 40% of all prescriptions in seven hospitals in Lebanon contained an error, of which 9% were unnecessary medication prescription.

The author set up a search alert on Google Scholar to be updated when new items that match his topic are published. In 2017, Hajjar, Bassatne, Cheaito, Naser El Dine, Traboulsy, Haddadin, Honein-AbouHaidar & Akl [ 41 ] studied the impact of only pharmaceutical representatives on drug prescription qualitatively and dispensing practices which were a negative impact. No later articles investigated other managing strategies in the Lebanese market regarding the topic of interest, leading to the particular need of this study. The next chapter formulated the hypothesis to be tested.

Research philosophy

The epistemological orientation of this research was the positivism philosophy. The ontological orientation was objectivism. To test theories, we adopted a deductive research analysis method. We opted a quantitative method to measure the impact of pharmaceutical marketing strategies on the prescribing behavior of physicians and physicians’ opinion regarding ethical acceptability of gifts and samples along with any other characteristics that interested us. Therefore, in our cross-sectional study, we measured the impact of 10 pharmaceutical promotional tools across two age groups of physicians, under- 43 and over 43. We compared the impact of these tools among the two genders (male and female) and among physicians practicing in a hospital located in a Lebanese urban country and physicians practicing in another hospital located in a Lebanese rural country. The participants were asked to mention any additional promotional tool that they considered as a motivator for their prescription behavior.

Data collection, study site, sampling method

Sampling was done by using a non-probability, quota, and convenience method. We chose this method because it is not feasible to draw a random probability-based sample of the population due to time considerations. The limitation of this method is that proportion of the entire population is not included in the sample group i.e. lack of representation of the entire population. Thus, the level of generalization of research findings compared to probability sampling is lower. The questionnaire format (Additional file 1 ) was written in english and was given to 364 Lebanese practicing physicians who are working in Lebanon at one of the two hospitals chosen by the author: a hospital in a Lebanese rural region and another one in a Lebanese urban region. However, 282 (response rate 77.47%) participated in the study and filled in the questionnaire completely. For this purpose, and to test the research hypotheses, a survey in a well- structured and self- administrated questionnaire format was developed and carried out by the researcher among the two hospitals of interest from March till April 2018. The questionnaire was piloted before final data collection to get at the thinking behind the answers so that we could accurately assess whether the questionnaire was filled out properly, whether respondents understood the questions, and whether the questions asked what we thought they were asking. Pre-testing also helped assess whether respondents were able and willing to provide the needed information. Twenty nine physicians undertook the pre-testing questionnaire, and their answers were excluded from the final analysis. No changes in the questions were recommended since the questions were clear and easy to understand. Thus, the link of the questionnaire was sent to each physician via “WhatsApp” after obtaining the approval from the Ethical Review Committee of each hospital. A reminder follow up notification was sent out after 7 days. The questionnaire included a covering letter questions to obtain demographic information about physicians, the influence of a list of 10 promotional tools used by most of the Lebanese pharmaceutical companies, questions regarding guidelines and physicians’ opinion regarding ethical acceptability of gifts and drug samples. Statistical Analysis was done using SPSS version 24 software for windows throughout the study to analyze the data.

Chi-square and Cramer’s V tests were carried out for the ten promotional tools identified through literature with the prescribing behavior of physicians that were respectively, shifting physicians’ drug prescription from one company to another if both drugs were generic and changing clinical practice after attending conferences and meetings.

Then the same test was applied to demographic parameters (gender and practice address) and physicians’ prescribing behavior. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. Spearman’s Rho test was used to measure the strength of association between ordinal variables (age range, receiving of the Lebanese code of ethics and physicians’ prescribing behavior).

Doctors’ prescription behavior of drugs was taken as a dependent variable.

As independent variables, 10 main promotional tools used by pharmaceutical firms were taken into consideration, i.e. visits of medical representatives, sales calls made by pharmaceutical companies, drug samples, promotional drug brochures, medical equipment as gifts, low-cost gifts, sponsorship for travel or personal tour or expenses in conferences, direct mails, subscription of journals and participation by company in continuing medical education conferences. Also, physicians’ demographic parameters and their ethical opinion were considered as mediating variables. Reliability test and validating data were done using IBM SPSS statistics version 24 software, and the results showed that no rules were violated.

Hypotheses development

As mentioned above, this study examined the impact of pharmaceutical marketing strategies on Lebanese physicians prescribing pattern concerning their demographic variables. Moreover, this study tested whether physicians consider gifts and samples acceptance as an ethical practice or an unethical one. For this purpose, the author addressed some questions that marketing managers of the drug companies are interested in: what is the most effective promotional tool in motivating Lebanese physicians to prescribe drugs? Do physicians’ demographic variables affect their perception towards different pharmaceutical marketing strategies? Do ethical codes affect physicians’ acceptance of gifts and samples? To answers these questions, this study formulated hypotheses based on theoretical background and summarized them in Table 2 below.

H1: Pharmaceutical marketing strategies change the prescribing behavior of physicians.

H2: Accepting gifts by physicians is unethical.

H3: Physicians with practices in rural settings are less likely to prescribe new drugs than are physicians operating in urban environments.

H4: Younger physicians are less likely to prescribe from new product categories.

H5: The probability of prescribing from a new drug category is greater among male than female physicians.

Two hundred eighty-two (response rate 77.47%) participated in the study and filled in the questionnaire completely. The majority of male practicing physicians liked to participate in the survey questionnaire (71.63%).

Results (Table 3 ) showed that 8 out of 10 dimensions taken as pharmaceutical marketing strategies were correlated to physicians prescribing behavior that is shifting drug prescription from one company to another if both were generic while seven dimensions out of 10 were correlated to this prescribing behavior that is changing clinical practice after attending conferences and meetings.

According to this study, the strategies used by pharmaceutical companies to promote their drugs demonstrated a correlation and a substantial relationship with physicians’ prescribing behavior. Therefore, the first hypothesis (there’s a relationship between pharmaceutical marketing strategies and the prescribing behavior of physicians) was accepted. Physicians declared that different promotional tools influenced them.

As shown in Table 4 , the majority of these promotional tools were mostly or sometimes motivating physicians to prescribe promoted drugs. The two first tools that the majority of physicians agreed to be motivated mainly by were visits of medical representatives (34.8%) and drug samples (34.8%). Most physicians were sometimes influenced by promotional drug brochures (44.7%), medical equipment as gifts (41.5%). More than half of physicians (54.3%) agreed to be never influenced by sales calls made by pharmaceutical companies, and scarce were physicians who declared to be always affected by a particular pharmaceutical marketing strategy.

The results showed that pharmaceutical companies’ promotional tools moderately motivated physicians. Visits of medical representatives (34.8%), drug samples (34.8%), participation by the company in continuing medical education conferences (31.6%), sponsorship for travel/ expenses in conferences/ sponsorship for a personal tour (28%) could be considered as the most influential tools.

These results showed that practicing physicians didn’t add any new promotional tool other than those we suggested in the questionnaire. However, their answers revealed a need for more scientific evidence provided by continual medical education and by well-educated medical representatives. This scientific evidence will help them to make the decision and to prescribe the best drug among the others.

Moreover, results shown in Table 5 revealed that physicians considered gifts’ acceptance as a non-ethical practice and 53% of them used free samples offered by pharmaceutical companies to treat their patients. Therefore, the second hypothesis was rejected.

H 3 was moderately accepted showing that there is a relationship between physicians prescribing pattern and the location of practice where changing in prescribing practices was more observable among physicians practicing in a hospital located in a rural region. H 4 was moderately accepted showing that there was a relationship between physician’s ages and prescribing pattern which is shifting generic drug prescription from one company to another. Regarding the last hypothesis, there was a relationship between physician’s gender and shifting drug prescription from one company to another, and H 5 was accepted (Table 6 ).

Chi-square and Cramer’s v tests reveal that physicians’ prescribing behaviors are correlated with pharmaceutical promotional tools used in the Lebanese market. It was found that physicians are motivated by pharmaceutical companies’ promotional tools to prescribe promoted drugs. Similarly, some other studies found a direct correlation between physicians’ prescribing patterns and pharmaceutical promotional tools [ 20 , 29 , 30 ]. This can easily be explained by the fact that the persuasive effect of pharmaceutical marketing strategies put extra pressure on physicians to prescribe onerous, expensive drugs even when a cheaper generic drug would be appropriate [ 4 ].

This study found that physicians consider the following promotional tools as the most influential tools among the ten tools tested: visits of medical representatives, drug samples, participation by the company in continuing medical education conferences and sponsorship for traveling and personal tours. Thus, visits to medical representatives been perceived to be the most important and the most influential tool. Researchers suggest that physicians rely heavily on commercial sources of information such as detailer and that the more doctors rely on commercial sources of information, the less likely they are to prescribe drugs in a manner consistent with patient needs. Information provided by detailers is often biased and sometimes dangerously misleading [ 42 , 43 ].

Regarding gift acceptance, the results of this study showed that there is no statistically significant difference among physicians who accept low and/or high-cost gifts and those who don’t. Moreover, statistically, there is no significance among physicians who consider the continuous supply of gifts (low and/or high-cost) at every visit of the medical representative as not justifiable and those who consider it as justifiable. However, the results showed that more physicians consider low cost-gift acceptance as an ethical practice than those who don’t (37.6%), but their continuous supply at every visit of the medical representative is more considered as not ethical (63.1%). This high percentage of physicians who do not accept the continuous supply of low-cost gifts means that some of the participated physicians in the study are not ashamed of the behavior of moderately accepting low-cost gifts. However, they know that gift acceptance is unethical, and they don’t accept it continuously. This could be explained by the fact that the Lebanese physicians are aware and are more considering the acceptance of small, low-cost gifts permissible than non-permissible even if the majority of them didn’t receive a copy of the 2016 code of ethics for medicinal products [ 19 ]. While in other studies, such as in Austria and Saudi Arabia, larger percent (66–80%) of physicians accept gifts from drug companies [ 44 , 45 ].

For high-cost gifts, this study showed that most Lebanese physicians consider their acceptance as unethical (74.8%). The same is for the continuous supply of high cost-gifts (71.6%). While in Iraq and the United States of America, respectively 59 and 74.6% of physicians consider the acceptance of high-cost gifts inappropriate and unethical [ 44 , 45 ]. Those high percentages can be explained by that physicians feel that small gifts do not significantly alter or influence their prescribing pattern but expensive gifts might do so [ 46 ]. Again, these results may give us a hope in that physicians are conscious of unethical expensive gifts’ acceptance.

However, social scientists demonstrated that the tendency to reciprocate for gifts, even the small ones, is a powerful influence on people’s behavior. Individuals who receive gifts are often unable to remain objective. Whenever a physician accepts an award, an implicit relationship is established between the doctor and the company resulting in a prescription [ 3 ]. Physicians not acknowledging the power of receiving small gifts are more likely to be influenced because their defenses are down.

Regarding free samples, it was found in this study that most physicians use free samples to treat their patients (53%). These free samples could be provided for a poor patient who cannot afford to buy it and therefore who manages drug costs in the long term or in some cases to initiate treatment for a new patient.

This study showed that Lebanese physicians significantly shift drug prescription from one company to another if both drugs were generic and they change their clinical practice. This means that the prescribing behavior of Lebanese physicians is highly influenced by pharmaceutical marketing strategies. Similarly, there are some other studies where it was showed that physicians who are interested in drug promotion and who have a positive attitude toward pharmaceutical companies’ promotions adopt rapidly prescription sponsored medications [ 47 ]. From another hand, previous studies showed that most physicians don’t feel that drug companies influence their prescribing pattern [ 48 ]. The difference in this study may result from the indirect way of questioning, which may provide a more realistic result than other studies.

It was found that the perception of practicing physicians towards some promotional tools’ influence on their prescribing behavior is dependent on demographic factors that are practice address, age, and gender of physicians. Practicing physicians in the hospital located in the urban region assign a greater shift in prescribing drugs as compared to physicians practicing in the hospital located in the rural area. Usually, physicians practicing in the rural areas do not get high access to new information unlike physicians practicing in urban regions; this may be one of the reasons for assigning more significant influence to promotional tools by physicians practicing in the urban area. These findings are in accordance with the findings in previous researches by Tamblyn, McLeod, Hanley, Girard, and Hurley (2003) [ 22 ] and Cutts and Tett (2003) [ 49 ].

This empirical investigation confirmed that older physicians assign to be less influenced by pharmaceutical promotional tools as compared to younger physicians. As older the consumers (physicians) are, the more the view is negative towards technology, and the lower the use of various technologies (including the prescription of new drugs). In other words, older physicians are less modern than younger ones. These results are similar to the results found by Peay and Peay’s work in 1994 [ 50 ]. They suggested that older doctors were less innovative than younger ones.

Moreover, it was found in this study that the probability of prescribing from a new drug category (prescribing behavior) is greater among female than male physicians.

The general questions which were asked to practicing physicians to get more insights regarding the improvement of regulations framing the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies confirm the previous results obtained in this study. The answers showed that physicians investigated are conscious and aware of the need for more strengthening the ethical norms regulating their interaction with pharmaceutical industries. This interaction should be with medical representatives holding a certificate of professional and ethical capability to execute a given profession, and the number of visits should be regulated. Besides, physicians appreciate that pharmaceutical companies invite them to international congresses which means that they are interested in acquiring scientific knowledge.

Contributions of this research (theoretical, managerial)

This present study adds to the previous researches that conceptualize the fact that clinical practice decision making is a dynamic process which is affected by some pharmaceutical marketing strategies. Although the doctors generally use the pharmacological criteria in deciding which drug to prescribe, the findings of the study show that the demographic influences are also rated essential factors in the doctor’s decision to prescribe. The present study identified and analyzed the demographic variables like the gender of the doctors, the age of doctors and practice location of the doctors and the results reveal that they have an impact on prescribing behavior.

Our empirical investigation of physicians’ prescription behavior in Lebanon and its findings contribute to an improvement in the marketing practices of the pharmaceutical industry. Knowing that when prescribing habits are once learned, it may be difficult to change them, pharmaceutical managers should use appropriate promotional tools and target the category of physicians that are more influenced than the others. Therefore, the pharmaceutical company optimizes its marketing expenditures better than competitors and increases its sales with lower promotional budgets.

Therefore, the results imply that public policymakers should take prescription behavior seriously and conduct more prescription behavior studies at regular intervals, to precisely understand the impact of tangible rewards on physicians’ prescribing patterns and control unethical practices by both pharmaceutical companies and physicians. So, it is recommended to establish guidelines and to be sure that all physicians are aware of them and always to keep physicians updated regarding new guidelines and to control guidelines’ implementation to limit unethical promotion practices and unethical prescription patterns.

These results, although not surprising, add to the existing body of information because they come from direct observations of behavior in a non-probability, quota and convenience sample.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although this study is limited by maturation that is quite simply, people change, and the ways in which they change may have implications for the dependent variable, but it rings a bell of danger by the non-ethical interaction between practicing physicians and drug companies in Lebanon, which negatively affect physicians prescribing behavior and in turn affect patients’ health negatively. It is suggested for future research to replicate this study and include pharmaceutical companies and pharmacists since they play a role in the pharmaceutical market. Also, the same research can be replicated by including more demographic factors of the physicians.

Most of the investigated physicians change their prescribing behavior, and it can simply be concluded that prescribing pattern of Lebanese physicians is negatively affected by promotion tactics.

It can be concluded that the pharmaceutical marketers have to understand the real needs, beliefs, and behaviors of physicians towards their marketing and promotional tools while taking into account physicians’ demographic factors and physicians’ opinion regarding ethical acceptability of gifts and samples. Physicians are the most substantial determinants in pharmaceutical sales by deciding which drug will be used by patients. Influencing the physician is a key to pharmaceutical sales. The marketing efforts of drug companies must target female, young physicians practicing in rural regions. This might generally be the most influenced category of practicing physicians.

Chiu, H. (2005). Selling drugs: marketing strategies in the pharmaceutical industry and their effect on healthcare and research. Explorations.

Marco CA, Moskop JC, Solomon RC, Geiderman JM, Larkin GL. Gifts to physicians from the pharmaceutical industry: an ethical analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(5):513–21.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Goyal R, Pareek P. A review article on prescription behavior of doctors, influenced by the medical representative in Rajasthan, India. IOSR J Bus Manag. 2013;8(1):56–60.

Article Google Scholar

De Laat E, Windmeijer F, Douven RCMH. How does pharmaceutical marketing influence doctors’ prescribing behaviour? Den Haag: CPB; 2002.

Google Scholar

Seaman M. New pharma ethics rules eliminate gifts and meals. USA Today. 2008.

Gönül FF, Carter F, Petrova E, Srinivasan K. Promotion of prescription drugs and its impact on physicians’ choice behavior. J Mark. 2001;65(3):79–90.

Al-Areefi MA, Hassali MA. Physicians’ perceptions of medical representative visits in Yemen: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):331.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tahmasebi N, Kebriaeezadeh A. Evaluation of factors affecting prescribing behaviors, in Iran pharmaceutical market by econometric methods. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14(2):651.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Buckley J. Pharmaceutical marketing-time for change. Electron J Bus Ethics Org Stud. 2004;9(2).

El-Jardali, F., & Fadlallah, R. (2015). retrieved in, http://www.executive-magazine.com/opinion/irrational-drug-prescription-in-lebanon .

Lamont J, Favor C. Distributive justice. In: Handbook of political theory; 2004. p. 1.

Sen A, Siebert H. Markets and the Freedom to Choose. In: The ethical foundations of the market economy. Tubingen: J.C.B. Mohr; 1994.

Mack P. Utilitarian ethics in healthcare. Int J Comput Integr Manuf. 2004;12(3):63–72.

Lantos GP. In Defense of advertising: arguments from reason, ethical egoism, and laissez-faire capitalism; 1995.

Kirkpatrick J. Ethical Theory in Marketing. In: Marketing Education: Challenges, Opportunities and Solutions: Proceedings of the Western Marketing Educators’ Association Conference; 1989. p. 50–3.

Brett AS, Burr W, Moloo J. Are gifts from pharmaceutical companies ethically problematic?: a survey of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(18):2213–8.

Kitchener KS. Intuition, critical evaluation and ethical principles: the foundation for ethical decisions in counseling psychology. Couns Psychol. 1984;12(3):43–55.

Denman RB, Purow B, Rubenstein R, Miller DL. Hammerhead ribozyme cleavage of hamster prion pre-mRNA in complex cell-free model systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186(2):1171–7.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

The Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), 2016, The Lebanese Code of Ethics: a New Milestone.

Van den Bulte C, Lilien GL. Medical innovation revisited: social contagion versus marketing effort. Am J Sociol. 2001;106(5):1409–35.

Berndt ER, Pindyck RS, Azoulay P. Consumption externalities and diffusion in pharmaceutical markets: antiulcer drugs. J Ind Econ. 2003;51(2):243–70.

Tamblyn R, McLeod P, Hanley JA, Girard N, Hurley J. Physician and practice characteristics associated with the early utilization of new prescription drugs. Med Care. 2003;41(8):895–908.

Gilly MC, Zeithaml VA. The elderly consumer and adoption of technologies. J Consum Res. 1985;12(3):353–7.

Mitchell VW, Walsh G. Gender differences in German consumer decision-making styles. J Consum Behav. 2004;3(4):331–46.

Chang J, Samuel N. Internet shopper demographics and buying behaviour in Australia. J Am Acad Bus. 2004;5(1/2):171–6.

Fischer E, Arnold SJ. Sex, gender identity, gender role attitudes, and consumer behavior. Psychol Mark. 1994;11(2):163–82.

Inman W, Pearce G. Prescriber profile and post-marketing surveillance. Lancet. 1993;342(8872):658–61.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations: Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Narayanan S, Manchanda P, Chintagunta PK. Temporal differences in the role of marketing communication in new product categories. J Mark Res. 2005;42(3):278–90.

Hahn M, Park S, Krishnamurthi L, Zoltners AA. Analysis of new product diffusion using a four-segment trial-repeat model. Mark Sci. 1994;13(3):224–47.

Vakratsas D, Ambler T. How advertising works: what do we really know? J Mark. 1999;63(1):26–43.

Dorfman R, Steiner PO. Optimal advertising and optimal quality. Am Econ Rev. 1954:826–36.

Turley LW, LeBlanc RP. Evoked sets: a dynamic process model. J Mark Theory Pract. 1995;3(2):28–36.

Mott DA, Schommer JC, Doucette WR, Kreling DH. Agency theory, drug formularies, and drug product selection: implications for public policy. J Public Policy Mark. 1998:287–95.

Netemeyer R, Ryn MV, Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30.

Eisenhardt KM. Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev. 1989;14(1):57–74.

Broderick A. Role theory and the management of service encounters. Serv Ind J. 1999;19(2):117–31.

Barnes ML. Marketing to a segment of one. Pharm Exec. 2003;23(3):110.

Sheth JN, Parvatiyar A. Relationship marketing in consumer markets: antecedents and consequences. J Acad Mark Sci. 1995;23(4):255–71.

Hajjar R, Bassatne A, Cheaito MA, Naser El Dine R, Traboulsy S, Haddadin F, Honein-AbouHaidar G, Akl EA. Characterizing the interaction between physicians, pharmacists and pharmaceutical representatives in a middle-income country: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9).

Avorn J, Chren M, Hartley R. Scientific versus commercial sources of influence on the prescribing behavior of physicians. Am J Med. 1982;73(1):4–8.

Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273(16):1296–8.

McNeill PM, Kerridge IH, Henry DA, Stokes B, Hill SR, Newby D, et al. Giving and receiving of gifts between pharmaceutical companies and medical specialists in Australia. Intern Med J. 2006;36(9):571–8.

Alosaimi F, Alkaabba A, Qadi M, Albahlal A, Alabdulkarim Y, Alabduljabbar M, et al. Acceptance of pharmaceutical gifts. Variability by specialty and job rank in a Saudi healthcare setting. Saudi Med J. 2013;34(8):854–60.

PubMed Google Scholar

Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, Blumenthal D, Chimonas SC, Cohen JJ, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295(4):429–33.

Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283(3):373–80.

Steunman M, Shilpak M, McPhee S. Of principles and pens: attitudes and practices of medicine house staff toward pharmaceutical industry promotions. Am J Med. 2001;110(7):551–7.

Cutts C, Tett SE. Influences on doctors’ prescribing: is geographical remoteness a factor? Aust J Rural Health. 2003;11(3):124–30.

Peay MY, Peay ER. Innovation in high risk drug therapy. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(1):39–52.

Alssageer MA, Kowalski SR. What do Libyan doctors perceive as the benefits, ethical issues and influences of their interactions with pharmaceutical company representatives? Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:132.

Ghaith A, Aldmour H, Alabbadi H. Investigating the effect of pharmaceutical companies’ gifts on doctors’ prescribing behavior in Jordan. Eur J Soc Sci. 2012;36(4):528–36.

Mikhael EM, Alhilali DN. Gift acceptance and its effect on prescribing behavior among Iraqi specialist physicians. Pharmacol Pharm. 2014;5(7):705–15.

Download references

Acknowledgments

No Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the large amount of data analyzed and because it contains very sensitive and private information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Independent Researcher, Zahle, Lebanon

Micheline Khazzaka

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MK contributed alone to all what was needed to accomplish this article. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Micheline Khazzaka .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The ethical approvals were received from the ethical review committees of “Tel Chiha Hospital” and from “Saint George Hospital University Medical Center” where the survey was run.

The first ethical review committee gave oral approval to send the questionnaire to its physicians as I already know the head of this committee by its person Dr. Raymond Khazzaka and he accepted that the physicians of the hospital participate in the survey.

Regarding the second hospital, I received approval that was sent to me by email from the head of the ethical review committee.

In both cases, physicians received a link via “Whatsapp” directing them to participate in the questionnaire built via a software “QuestionPro” and to fill it if they want to, they had the choice to participate or not in the survey when the questionnaire was sent to them. The results of the completed questionnaires sent back by the physicians were then recorded in this software with all the information answered.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Questionnaire format. (DOCX 220 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khazzaka, M. Pharmaceutical marketing strategies’ influence on physicians' prescribing pattern in Lebanon: ethics, gifts, and samples. BMC Health Serv Res 19 , 80 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3887-6

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2018

Accepted : 08 January 2019

Published : 30 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-3887-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Pharmaceutical marketing

- Prescribing behavior

- Physicians’ profile

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Ethics

Considerations for applying bioethics norms to a biopharmaceutical industry setting

Luann e. van campen.

1 Ethics Matters, LLC, 5868 E. 71st Street, E-125, Indianapolis, IN 46220 USA

2 Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN USA

Tatjana Poplazarova

3 GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium

Donald G. Therasse

Michael turik.

4 Indiana University Institutional Review Board, Indianapolis, IN USA

Associated Data

Not applicable.

The biopharmaceutical industry operates at the intersection of life sciences, clinical research, clinical care, public health, and business, which presents distinct operational and ethical challenges. This setting merits focused bioethics consideration to complement legal compliance and business ethics efforts. However, bioethics as applied to a biopharmaceutical industry setting often is construed either too broadly or too narrowly with little examination of its proper scope.

Any institution with a scientific or healthcare mission should engage bioethics norms to navigate ethical issues that arise from the conduct of biomedical research, delivery of clinical care, or implementation of public health programs. It is reasonable to assume that while bioethics norms must remain constant, their application will vary depending on the characteristics of a given setting. Context “specification” substantively refines ethics norms for a particular discipline or setting and is an expected, needed and progressive ethical activity. In order for this activity to be meaningful, the scope for bioethics application and the relevant contextual factors of the setting need to be delineated and appreciated. This paper defines biopharmaceutical bioethics as: the application of bioethics norms (concepts, principles, and rules) to the research, development, supply, commercialization, and clinical use of biopharmaceutical healthcare products . It provides commentary on this definition, and presents five contextual factors that need to be considered when applying bioethics norms to a biopharmaceutical industry setting: (1) dual missions; (2) timely and pragmatic guidance; (3) resource stewardship; (4) multiple stakeholders; and (5) operational complexity.