- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 February 2017

Blended learning effectiveness: the relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes

- Mugenyi Justice Kintu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4500-1168 1 , 2 ,

- Chang Zhu 2 &

- Edmond Kagambe 1

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 14 , Article number: 7 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

752k Accesses

219 Citations

37 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper investigates the effectiveness of a blended learning environment through analyzing the relationship between student characteristics/background, design features and learning outcomes. It is aimed at determining the significant predictors of blended learning effectiveness taking student characteristics/background and design features as independent variables and learning outcomes as dependent variables. A survey was administered to 238 respondents to gather data on student characteristics/background, design features and learning outcomes. The final semester evaluation results were used as a measure for performance as an outcome. We applied the online self regulatory learning questionnaire for data on learner self regulation, the intrinsic motivation inventory for data on intrinsic motivation and other self-developed instruments for measuring the other constructs. Multiple regression analysis results showed that blended learning design features (technology quality, online tools and face-to-face support) and student characteristics (attitudes and self-regulation) predicted student satisfaction as an outcome. The results indicate that some of the student characteristics/backgrounds and design features are significant predictors for student learning outcomes in blended learning.

Introduction

The teaching and learning environment is embracing a number of innovations and some of these involve the use of technology through blended learning. This innovative pedagogical approach has been embraced rapidly though it goes through a process. The introduction of blended learning (combination of face-to-face and online teaching and learning) initiatives is part of these innovations but its uptake, especially in the developing world faces challenges for it to be an effective innovation in teaching and learning. Blended learning effectiveness has quite a number of underlying factors that pose challenges. One big challenge is about how users can successfully use the technology and ensuring participants’ commitment given the individual learner characteristics and encounters with technology (Hofmann, 2014 ). Hofmann adds that users getting into difficulties with technology may result into abandoning the learning and eventual failure of technological applications. In a report by Oxford Group ( 2013 ), some learners (16%) had negative attitudes to blended learning while 26% were concerned that learners would not complete study in blended learning. Learners are important partners in any learning process and therefore, their backgrounds and characteristics affect their ability to effectively carry on with learning and being in blended learning, the design tools to be used may impinge on the effectiveness in their learning.

This study tackles blended learning effectiveness which has been investigated in previous studies considering grades, course completion, retention and graduation rates but no studies regarding effectiveness in view of learner characteristics/background, design features and outcomes have been done in the Ugandan university context. No studies have also been done on how the characteristics of learners and design features are predictors of outcomes in the context of a planning evaluation research (Guskey, 2000 ) to establish the effectiveness of blended learning. Guskey ( 2000 ) noted that planning evaluation fits in well since it occurs before the implementation of any innovation as well as allowing planners to determine the needs, considering participant characteristics, analyzing contextual matters and gathering baseline information. This study is done in the context of a plan to undertake innovative pedagogy involving use of a learning management system (moodle) for the first time in teaching and learning in a Ugandan university. The learner characteristics/backgrounds being investigated for blended learning effectiveness include self-regulation, computer competence, workload management, social and family support, attitude to blended learning, gender and age. We investigate the blended learning design features of learner interactions, face-to-face support, learning management system tools and technology quality while the outcomes considered include satisfaction, performance, intrinsic motivation and knowledge construction. Establishing the significant predictors of outcomes in blended learning will help to inform planners of such learning environments in order to put in place necessary groundwork preparations for designing blended learning as an innovative pedagogical approach.

Kenney and Newcombe ( 2011 ) did their comparison to establish effectiveness in view of grades and found that blended learning had higher average score than the non-blended learning environment. Garrison and Kanuka ( 2004 ) examined the transformative potential of blended learning and reported an increase in course completion rates, improved retention and increased student satisfaction. Comparisons between blended learning environments have been done to establish the disparity between academic achievement, grade dispersions and gender performance differences and no significant differences were found between the groups (Demirkol & Kazu, 2014 ).

However, blended learning effectiveness may be dependent on many other factors and among them student characteristics, design features and learning outcomes. Research shows that the failure of learners to continue their online education in some cases has been due to family support or increased workload leading to learner dropout (Park & Choi, 2009 ) as well as little time for study. Additionally, it is dependent on learner interactions with instructors since failure to continue with online learning is attributed to this. In Greer, Hudson & Paugh’s study as cited in Park and Choi ( 2009 ), family and peer support for learners is important for success in online and face-to-face learning. Support is needed for learners from all areas in web-based courses and this may be from family, friends, co-workers as well as peers in class. Greer, Hudson and Paugh further noted that peer encouragement assisted new learners in computer use and applications. The authors also show that learners need time budgeting, appropriate technology tools and support from friends and family in web-based courses. Peer support is required by learners who have no or little knowledge of technology, especially computers, to help them overcome fears. Park and Choi, ( 2009 ) showed that organizational support significantly predicts learners’ stay and success in online courses because employers at times are willing to reduce learners’ workload during study as well as supervisors showing that they are interested in job-related learning for employees to advance and improve their skills.

The study by Kintu and Zhu ( 2016 ) investigated the possibility of blended learning in a Ugandan University and examined whether student characteristics (such as self-regulation, attitudes towards blended learning, computer competence) and student background (such as family support, social support and management of workload) were significant factors in learner outcomes (such as motivation, satisfaction, knowledge construction and performance). The characteristics and background factors were studied along with blended learning design features such as technology quality, learner interactions, and Moodle with its tools and resources. The findings from that study indicated that learner attitudes towards blended learning were significant factors to learner satisfaction and motivation while workload management was a significant factor to learner satisfaction and knowledge construction. Among the blended learning design features, only learner interaction was a significant factor to learner satisfaction and knowledge construction.

The focus of the present study is on examining the effectiveness of blended learning taking into consideration learner characteristics/background, blended learning design elements and learning outcomes and how the former are significant predictors of blended learning effectiveness.

Studies like that of Morris and Lim ( 2009 ) have investigated learner and instructional factors influencing learning outcomes in blended learning. They however do not deal with such variables in the contexts of blended learning design as an aspect of innovative pedagogy involving the use of technology in education. Apart from the learner variables such as gender, age, experience, study time as tackled before, this study considers social and background aspects of the learners such as family and social support, self-regulation, attitudes towards blended learning and management of workload to find out their relationship to blended learning effectiveness. Identifying the various types of learner variables with regard to their relationship to blended learning effectiveness is important in this study as we embark on innovative pedagogy with technology in teaching and learning.

Literature review

This review presents research about blended learning effectiveness from the perspective of learner characteristics/background, design features and learning outcomes. It also gives the factors that are considered to be significant for blended learning effectiveness. The selected elements are as a result of the researcher’s experiences at a Ugandan university where student learning faces challenges with regard to learner characteristics and blended learning features in adopting the use of technology in teaching and learning. We have made use of Loukis, Georgiou, and Pazalo ( 2007 ) value flow model for evaluating an e-learning and blended learning service specifically considering the effectiveness evaluation layer. This evaluates the extent of an e-learning system usage and the educational effectiveness. In addition, studies by Leidner, Jarvenpaa, Dillon and Gunawardena as cited in Selim ( 2007 ) have noted three main factors that affect e-learning and blended learning effectiveness as instructor characteristics, technology and student characteristics. Heinich, Molenda, Russell, and Smaldino ( 2001 ) showed the need for examining learner characteristics for effective instructional technology use and showed that user characteristics do impact on behavioral intention to use technology. Research has dealt with learner characteristics that contribute to learner performance outcomes. They have dealt with emotional intelligence, resilience, personality type and success in an online learning context (Berenson, Boyles, & Weaver, 2008 ). Dealing with the characteristics identified in this study will give another dimension, especially for blended learning in learning environment designs and add to specific debate on learning using technology. Lin and Vassar, ( 2009 ) indicated that learner success is dependent on ability to cope with technical difficulty as well as technical skills in computer operations and internet navigation. This justifies our approach in dealing with the design features of blended learning in this study.

Learner characteristics/background and blended learning effectiveness

Studies indicate that student characteristics such as gender play significant roles in academic achievement (Oxford Group, 2013 ), but no study examines performance of male and female as an important factor in blended learning effectiveness. It has again been noted that the success of e- and blended learning is highly dependent on experience in internet and computer applications (Picciano & Seaman, 2007 ). Rigorous discovery of such competences can finally lead to a confirmation of high possibilities of establishing blended learning. Research agrees that the success of e-learning and blended learning can largely depend on students as well as teachers gaining confidence and capability to participate in blended learning (Hadad, 2007 ). Shraim and Khlaif ( 2010 ) note in their research that 75% of students and 72% of teachers were lacking in skills to utilize ICT based learning components due to insufficient skills and experience in computer and internet applications and this may lead to failure in e-learning and blended learning. It is therefore pertinent that since the use of blended learning applies high usage of computers, computer competence is necessary (Abubakar & Adetimirin, 2015 ) to avoid failure in applying technology in education for learning effectiveness. Rovai, ( 2003 ) noted that learners’ computer literacy and time management are crucial in distance learning contexts and concluded that such factors are meaningful in online classes. This is supported by Selim ( 2007 ) that learners need to posses time management skills and computer skills necessary for effectiveness in e- learning and blended learning. Self-regulatory skills of time management lead to better performance and learners’ ability to structure the physical learning environment leads to efficiency in e-learning and blended learning environments. Learners need to seek helpful assistance from peers and teachers through chats, email and face-to-face meetings for effectiveness (Lynch & Dembo, 2004 ). Factors such as learners’ hours of employment and family responsibilities are known to impede learners’ process of learning, blended learning inclusive (Cohen, Stage, Hammack, & Marcus, 2012 ). It was also noted that a common factor in failure and learner drop-out is the time conflict which is compounded by issues of family , employment status as well as management support (Packham, Jones, Miller, & Thomas, 2004 ). A study by Thompson ( 2004 ) shows that work, family, insufficient time and study load made learners withdraw from online courses.

Learner attitudes to blended learning can result in its effectiveness and these shape behavioral intentions which usually lead to persistence in a learning environment, blended inclusive. Selim, ( 2007 ) noted that the learners’ attitude towards e-learning and blended learning are success factors for these learning environments. Learner performance by age and gender in e-learning and blended learning has been found to indicate no significant differences between male and female learners and different age groups (i.e. young, middle-aged and old above 45 years) (Coldwell, Craig, Paterson, & Mustard, 2008 ). This implies that the potential for blended learning to be effective exists and is unhampered by gender or age differences.

Blended learning design features

The design features under study here include interactions, technology with its quality, face-to-face support and learning management system tools and resources.

Research shows that absence of learner interaction causes failure and eventual drop-out in online courses (Willging & Johnson, 2009 ) and the lack of learner connectedness was noted as an internal factor leading to learner drop-out in online courses (Zielinski, 2000 ). It was also noted that learners may not continue in e- and blended learning if they are unable to make friends thereby being disconnected and developing feelings of isolation during their blended learning experiences (Willging & Johnson, 2009). Learners’ Interactions with teachers and peers can make blended learning effective as its absence makes learners withdraw (Astleitner, 2000 ). Loukis, Georgious and Pazalo (2007) noted that learners’ measuring of a system’s quality, reliability and ease of use leads to learning efficiency and can be so in blended learning. Learner success in blended learning may substantially be affected by system functionality (Pituch & Lee, 2006 ) and may lead to failure of such learning initiatives (Shrain, 2012 ). It is therefore important to examine technology quality for ensuring learning effectiveness in blended learning. Tselios, Daskalakis, and Papadopoulou ( 2011 ) investigated learner perceptions after a learning management system use and found out that the actual system use determines the usefulness among users. It is again noted that a system with poor response time cannot be taken to be useful for e-learning and blended learning especially in cases of limited bandwidth (Anderson, 2004 ). In this study, we investigate the use of Moodle and its tools as a function of potential effectiveness of blended learning.

The quality of learning management system content for learners can be a predictor of good performance in e-and blended learning environments and can lead to learner satisfaction. On the whole, poor quality technology yields no satisfaction by users and therefore the quality of technology significantly affects satisfaction (Piccoli, Ahmad, & Ives, 2001 ). Continued navigation through a learning management system increases use and is an indicator of success in blended learning (Delone & McLean, 2003 ). The efficient use of learning management system and its tools improves learning outcomes in e-learning and blended learning environments.

It is noted that learner satisfaction with a learning management system can be an antecedent factor for blended learning effectiveness. Goyal and Tambe ( 2015 ) noted that learners showed an appreciation to Moodle’s contribution in their learning. They showed positivity with it as it improved their understanding of course material (Ahmad & Al-Khanjari, 2011 ). The study by Goyal and Tambe ( 2015 ) used descriptive statistics to indicate improved learning by use of uploaded syllabus and session plans on Moodle. Improved learning is also noted through sharing study material, submitting assignments and using the calendar. Learners in the study found Moodle to be an effective educational tool.

In blended learning set ups, face-to-face experiences form part of the blend and learner positive attitudes to such sessions could mean blended learning effectiveness. A study by Marriot, Marriot, and Selwyn ( 2004 ) showed learners expressing their preference for face-to-face due to its facilitation of social interaction and communication skills acquired from classroom environment. Their preference for the online session was only in as far as it complemented the traditional face-to-face learning. Learners in a study by Osgerby ( 2013 ) had positive perceptions of blended learning but preferred face-to-face with its step-by-stem instruction. Beard, Harper and Riley ( 2004 ) shows that some learners are successful while in a personal interaction with teachers and peers thus prefer face-to-face in the blend. Beard however dealt with a comparison between online and on-campus learning while our study combines both, singling out the face-to-face part of the blend. The advantage found by Beard is all the same relevant here because learners in blended learning express attitude to both online and face-to-face for an effective blend. Researchers indicate that teacher presence in face-to-face sessions lessens psychological distance between them and the learners and leads to greater learning. This is because there are verbal aspects like giving praise, soliciting for viewpoints, humor, etc and non-verbal expressions like eye contact, facial expressions, gestures, etc which make teachers to be closer to learners psychologically (Kelley & Gorham, 2009 ).

Learner outcomes

The outcomes under scrutiny in this study include performance, motivation, satisfaction and knowledge construction. Motivation is seen here as an outcome because, much as cognitive factors such as course grades are used in measuring learning outcomes, affective factors like intrinsic motivation may also be used to indicate outcomes of learning (Kuo, Walker, Belland, & Schroder, 2013 ). Research shows that high motivation among online learners leads to persistence in their courses (Menager-Beeley, 2004 ). Sankaran and Bui ( 2001 ) indicated that less motivated learners performed poorly in knowledge tests while those with high learning motivation demonstrate high performance in academics (Green, Nelson, Martin, & Marsh, 2006 ). Lim and Kim, ( 2003 ) indicated that learner interest as a motivation factor promotes learner involvement in learning and this could lead to learning effectiveness in blended learning.

Learner satisfaction was noted as a strong factor for effectiveness of blended and online courses (Wilging & Johnson, 2009) and dissatisfaction may result from learners’ incompetence in the use of the learning management system as an effective learning tool since, as Islam ( 2014 ) puts it, users may be dissatisfied with an information system due to ease of use. A lack of prompt feedback for learners from course instructors was found to cause dissatisfaction in an online graduate course. In addition, dissatisfaction resulted from technical difficulties as well as ambiguous course instruction Hara and Kling ( 2001 ). These factors, once addressed, can lead to learner satisfaction in e-learning and blended learning and eventual effectiveness. A study by Blocker and Tucker ( 2001 ) also showed that learners had difficulties with technology and inadequate group participation by peers leading to dissatisfaction within these design features. Student-teacher interactions are known to bring satisfaction within online courses. Study results by Swan ( 2001 ) indicated that student-teacher interaction strongly related with student satisfaction and high learner-learner interaction resulted in higher levels of course satisfaction. Descriptive results by Naaj, Nachouki, and Ankit ( 2012 ) showed that learners were satisfied with technology which was a video-conferencing component of blended learning with a mean of 3.7. The same study indicated student satisfaction with instructors at a mean of 3.8. Askar and Altun, ( 2008 ) found that learners were satisfied with face-to-face sessions of the blend with t-tests and ANOVA results indicating female scores as higher than for males in the satisfaction with face-to-face environment of the blended learning.

Studies comparing blended learning with traditional face-to-face have indicated that learners perform equally well in blended learning and their performance is unaffected by the delivery method (Kwak, Menezes, & Sherwood, 2013 ). In another study, learning experience and performance are known to improve when traditional course delivery is integrated with online learning (Stacey & Gerbic, 2007 ). Such improvement as noted may be an indicator of blended learning effectiveness. Our study however, delves into improved performance but seeks to establish the potential of blended learning effectiveness by considering grades obtained in a blended learning experiment. Score 50 and above is considered a pass in this study’s setting and learners scoring this and above will be considered to have passed. This will make our conclusions about the potential of blended learning effectiveness.

Regarding knowledge construction, it has been noted that effective learning occurs where learners are actively involved (Nurmela, Palonen, Lehtinen & Hakkarainen, 2003 , cited in Zhu, 2012 ) and this may be an indicator of learning environment effectiveness. Effective blended learning would require that learners are able to initiate, discover and accomplish the processes of knowledge construction as antecedents of blended learning effectiveness. A study by Rahman, Yasin and Jusoff ( 2011 ) indicated that learners were able to use some steps to construct meaning through an online discussion process through assignments given. In the process of giving and receiving among themselves, the authors noted that learners learned by writing what they understood. From our perspective, this can be considered to be accomplishment in the knowledge construction process. Their study further shows that learners construct meaning individually from assignments and this stage is referred to as pre-construction which for our study, is an aspect of discovery in the knowledge construction process.

Predictors of blended learning effectiveness

Researchers have dealt with success factors for online learning or those for traditional face-to-face learning but little is known about factors that predict blended learning effectiveness in view of learner characteristics and blended learning design features. This part of our study seeks to establish the learner characteristics/backgrounds and design features that predict blended learning effectiveness with regard to satisfaction, outcomes, motivation and knowledge construction. Song, Singleton, Hill, and Koh ( 2004 ) examined online learning effectiveness factors and found out that time management (a self-regulatory factor) was crucial for successful online learning. Eom, Wen, and Ashill ( 2006 ) using a survey found out that interaction, among other factors, was significant for learner satisfaction. Technical problems with regard to instructional design were a challenge to online learners thus not indicating effectiveness (Song et al., 2004 ), though the authors also indicated that descriptive statistics to a tune of 75% and time management (62%) impact on success of online learning. Arbaugh ( 2000 ) and Swan ( 2001 ) indicated that high levels of learner-instructor interaction are associated with high levels of user satisfaction and learning outcomes. A study by Naaj et al. ( 2012 ) indicated that technology and learner interactions, among other factors, influenced learner satisfaction in blended learning.

Objective and research questions of the current study

The objective of the current study is to investigate the effectiveness of blended learning in view of student satisfaction, knowledge construction, performance and intrinsic motivation and how they are related to student characteristics and blended learning design features in a blended learning environment.

Research questions

What are the student characteristics and blended learning design features for an effective blended learning environment?

Which factors (among the learner characteristics and blended learning design features) predict student satisfaction, learning outcomes, intrinsic motivation and knowledge construction?

Conceptual model of the present study

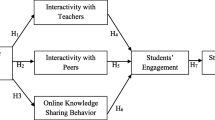

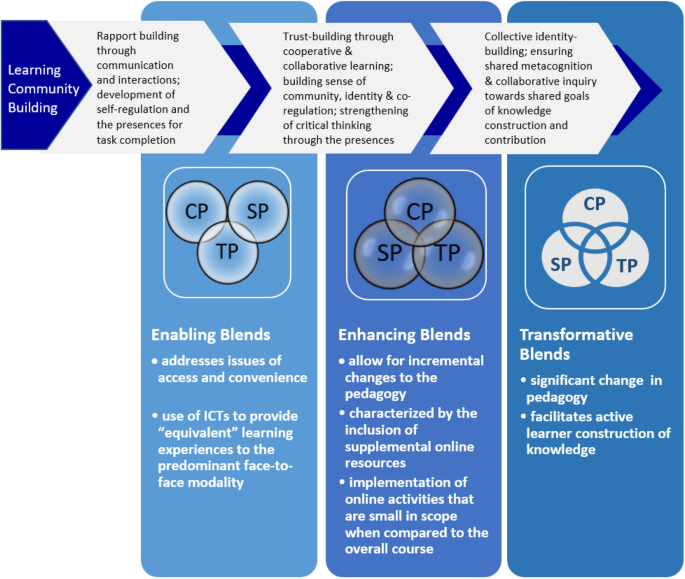

The reviewed literature clearly shows learner characteristics/background and blended learning design features play a part in blended learning effectiveness and some of them are significant predictors of effectiveness. The conceptual model for our study is depicted as follows (Fig. 1 ):

Conceptual model of the current study

Research design

This research applies a quantitative design where descriptive statistics are used for the student characteristics and design features data, t-tests for the age and gender variables to determine if they are significant in blended learning effectiveness and regression for predictors of blended learning effectiveness.

This study is based on an experiment in which learners participated during their study using face-to-face sessions and an on-line session of a blended learning design. A learning management system (Moodle) was used and learner characteristics/background and blended learning design features were measured in relation to learning effectiveness. It is therefore a planning evaluation research design as noted by Guskey ( 2000 ) since the outcomes are aimed at blended learning implementation at MMU. The plan under which the various variables were tested involved face-to-face study at the beginning of a 17 week semester which was followed by online teaching and learning in the second half of the semester. The last part of the semester was for another face-to-face to review work done during the online sessions and final semester examinations. A questionnaire with items on student characteristics, design features and learning outcomes was distributed among students from three schools and one directorate of postgraduate studies.

Participants

Cluster sampling was used to select a total of 238 learners to participate in this study. Out of the whole university population of students, three schools and one directorate were used. From these, one course unit was selected from each school and all the learners following the course unit were surveyed. In the school of Education ( n = 70) and Business and Management Studies ( n = 133), sophomore students were involved due to the fact that they have been introduced to ICT basics during their first year of study. Students of the third year were used from the department of technology in the School of Applied Sciences and Technology ( n = 18) since most of the year two courses had a lot of practical aspects that could not be used for the online learning part. From the Postgraduate Directorate ( n = 17), first and second year students were selected because learners attend a face-to-face session before they are given paper modules to study away from campus.

The study population comprised of 139 male students representing 58.4% and 99 females representing 41.6% with an average age of 24 years.

Instruments

The end of semester results were used to measure learner performance. The online self-regulated learning questionnaire (Barnard, Lan, To, Paton, & Lai, 2009 ) and the intrinsic motivation inventory (Deci & Ryan, 1982 ) were applied to measure the constructs on self regulation in the student characteristics and motivation in the learning outcome constructs. Other self-developed instruments were used for the other remaining variables of attitudes, computer competence, workload management, social and family support, satisfaction, knowledge construction, technology quality, interactions, learning management system tools and resources and face-to-face support.

Instrument reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was used to test reliability and the table below gives the results. All the scales and sub-scales had acceptable internal consistency reliabilities as shown in Table 1 below:

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics was conducted. Shapiro-Wilk test was done to test normality of the data for it to qualify for parametric tests. The test results for normality of our data before the t- test resulted into significant levels (Male = .003, female = .000) thereby violating the normality assumption. We therefore used the skewness and curtosis results which were between −1.0 and +1.0 and assumed distribution to be sufficiently normal to qualify the data for a parametric test, (Pallant, 2010 ). An independent samples t -test was done to find out the differences in male and female performance to explain the gender characteristics in blended learning effectiveness. A one-way ANOVA between subjects was conducted to establish the differences in performance between age groups. Finally, multiple regression analysis was done between student variables and design elements with learning outcomes to determine the significant predictors for blended learning effectiveness.

Student characteristics, blended learning design features and learning outcomes ( RQ1 )

A t- test was carried out to establish the performance of male and female learners in the blended learning set up. This was aimed at finding out if male and female learners do perform equally well in blended learning given their different roles and responsibilities in society. It was found that male learners performed slightly better ( M = 62.5) than their female counterparts ( M = 61.1). An independent t -test revealed that the difference between the performances was not statistically significant ( t = 1.569, df = 228, p = 0.05, one tailed). The magnitude of the differences in the means is small with effect size ( d = 0.18). A one way between subjects ANOVA was conducted on the performance of different age groups to establish the performance of learners of young and middle aged age groups (20–30, young & and 31–39, middle aged). This revealed a significant difference in performance (F(1,236 = 8.498, p < . 001).

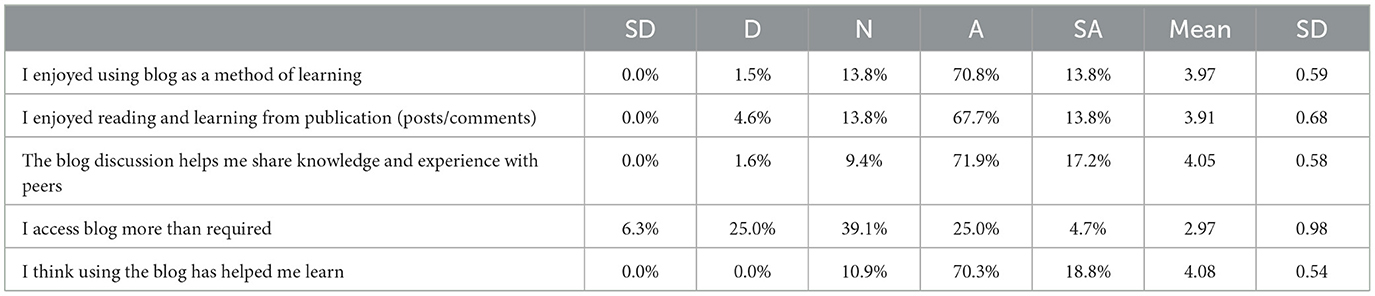

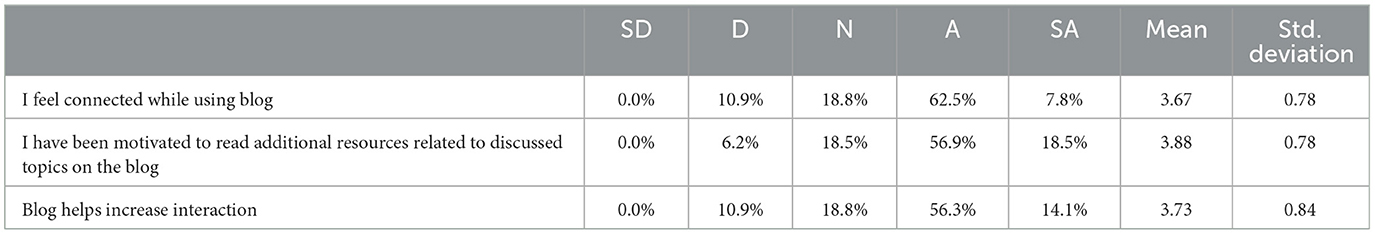

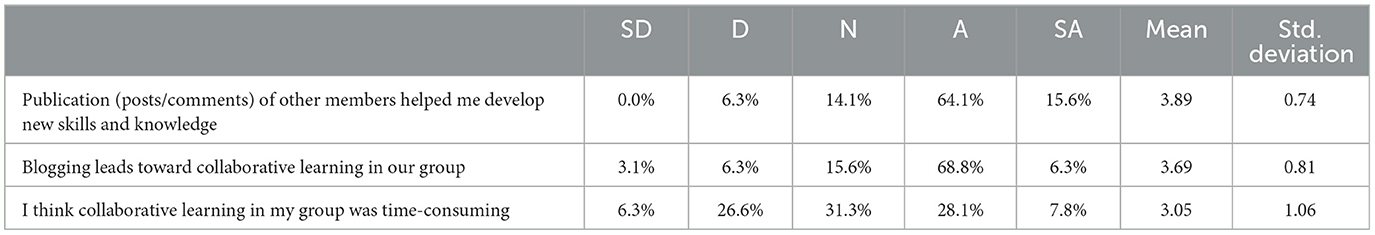

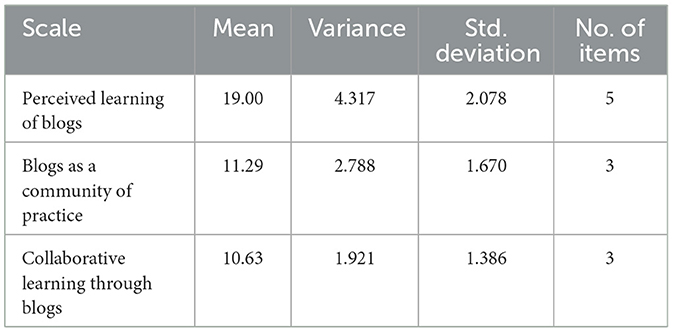

Average percentages of the items making up the self regulated learning scale are used to report the findings about all the sub-scales in the learner characteristics/background scale. Results show that learner self-regulation was good enough at 72.3% in all the sub-scales of goal setting, environment structuring, task strategies, time management, help-seeking and self-evaluation among learners. The least in the scoring was task strategies at 67.7% and the highest was learner environment structuring at 76.3%. Learner attitude towards blended learning environment is at 76% in the sub-scales of learner autonomy, quality of instructional materials, course structure, course interface and interactions. The least scored here is attitude to course structure at 66% and their attitudes were high on learner autonomy and course interface both at 82%. Results on the learners’ computer competences are summarized in percentages in the table below (Table 2 ):

It can be seen that learners are skilled in word processing at 91%, email at 63.5%, spreadsheets at 68%, web browsers at 70.2% and html tools at 45.4%. They are therefore good enough in word processing and web browsing. Their computer confidence levels are reported at 75.3% and specifically feel very confident when it comes to working with a computer (85.7%). Levels of family and social support for learners during blended learning experiences are at 60.5 and 75% respectively. There is however a low score on learners being assisted by family members in situations of computer setbacks (33.2%) as 53.4% of the learners reported no assistance in this regard. A higher percentage (85.3%) is reported on learners getting support from family regarding provision of essentials for learning such as tuition. A big percentage of learners spend two hours on study while at home (35.3%) followed by one hour (28.2%) while only 9.7% spend more than three hours on study at home. Peers showed great care during the blended learning experience (81%) and their experiences were appreciated by the society (66%). Workload management by learners vis-à-vis studying is good at 60%. Learners reported that their workmates stand in for them at workplaces to enable them do their study in blended learning while 61% are encouraged by their bosses to go and improve their skills through further education and training. On the time spent on other activities not related to study, majority of the learners spend three hours (35%) while 19% spend 6 hours. Sixty percent of the learners have to answer to someone when they are not attending to other activities outside study compared to the 39.9% who do not and can therefore do study or those other activities.

The usability of the online system, tools and resources was below average as shown in the table below in percentages (Table 3 ):

However, learners became skilled at navigating around the learning management system (79%) and it was easy for them to locate course content, tools and resources needed such as course works, news, discussions and journal materials. They effectively used the communication tools (60%) and to work with peers by making posts (57%). They reported that online resources were well organized, user friendly and easy to access (71%) as well as well structured in a clear and understandable manner (72%). They therefore recommended the use of online resources for other course units in future (78%) because they were satisfied with them (64.3%). On the whole, the online resources were fine for the learners (67.2%) and useful as a learning resource (80%). The learners’ perceived usefulness/satisfaction with online system, tools, and resources was at 81% as the LMS tools helped them to communicate, work with peers and reflect on their learning (74%). They reported that using moodle helped them to learn new concepts, information and gaining skills (85.3%) as well as sharing what they knew or learned (76.4%). They enjoyed the course units (78%) and improved their skills with technology (89%).

Learner interactions were seen from three angles of cognitivism, collaborative learning and student-teacher interactions. Collaborative learning was average at 50% with low percentages in learners posting challenges to colleagues’ ideas online (34%) and posting ideas for colleagues to read online (37%). They however met oftentimes online (60%) and organized how they would work together in study during the face-to-face meetings (69%). The common form of communication medium frequently used by learners during the blended learning experience was by phone (34.5%) followed by whatsapp (21.8%), face book (21%), discussion board (11.8%) and email (10.9%). At the cognitive level, learners interacted with content at 72% by reading the posted content (81%), exchanging knowledge via the LMS (58.4%), participating in discussions on the forum (62%) and got course objectives and structure introduced during the face-to-face sessions (86%). Student-teacher interaction was reported at 71% through instructors individually working with them online (57.2%) and being well guided towards learning goals (81%). They did receive suggestions from instructors about resources to use in their learning (75.3%) and instructors provided learning input for them to come up with their own answers (71%).

The technology quality during the blended learning intervention was rated at 69% with availability of 72%, quality of the resources was at 68% with learners reporting that discussion boards gave right content necessary for study (71%) and the email exchanges containing relevant and much needed information (63.4%) as well as chats comprising of essential information to aid the learning (69%). Internet reliability was rated at 66% with a speed considered averagely good to facilitate online activities (63%). They however reported that there was intermittent breakdown during online study (67%) though they could complete their internet program during connection (63.4%). Learners eventually found it easy to download necessary materials for study in their blended learning experiences (71%).

Learner extent of use of the learning management system features was as shown in the table below in percentage (Table 4 ):

From the table, very rarely used features include the blog and wiki while very often used ones include the email, forum, chat and calendar.

The effectiveness of the LMS was rated at 79% by learners reporting that they found it useful (89%) and using it makes their learning activities much easier (75.2%). Moodle has helped learners to accomplish their learning tasks more quickly (74%) and that as a LMS, it is effective in teaching and learning (88%) with overall satisfaction levels at 68%. However, learners note challenges in the use of the LMS regarding its performance as having been problematic to them (57%) and only 8% of the learners reported navigation while 16% reported access as challenges.

Learner attitudes towards Face-to-face support were reported at 88% showing that the sessions were enjoyable experiences (89%) with high quality class discussions (86%) and therefore recommended that the sessions should continue in blended learning (89%). The frequency of the face-to-face sessions is shown in the table below as preferred by learners (Table 5 ).

Learners preferred face-to-face sessions after every month in the semester (33.6%) and at the beginning of the blended learning session only (27.7%).

Learners reported high intrinsic motivation levels with interest and enjoyment of tasks at 83.7%, perceived competence at 70.2%, effort/importance sub-scale at 80%, pressure/tension reported at 54%. The pressure percentage of 54% arises from learners feeling nervous (39.2%) and a lot of anxiety (53%) while 44% felt a lot of pressure during the blended learning experiences. Learners however reported the value/usefulness of blended learning at 91% with majority believing that studying online and face-to-face had value for them (93.3%) and were therefore willing to take part in blended learning (91.2%). They showed that it is beneficial for them (94%) and that it was an important way of studying (84.3%).

Learner satisfaction was reported at 81% especially with instructors (85%) high percentage reported on encouraging learner participation during the course of study 93%, course content (83%) with the highest being satisfaction with the good relationship between the objectives of the course units and the content (90%), technology (71%) with a high percentage on the fact that the platform was adequate for the online part of the learning (76%), interactions (75%) with participation in class at 79%, and face-to-face sessions (91%) with learner satisfaction high on face-to-face sessions being good enough for interaction and giving an overview of the courses when objectives were introduced at 92%.

Learners’ knowledge construction was reported at 78% with initiation and discovery scales scoring 84% with 88% specifically for discovering the learning points in the course units. The accomplishment scale in knowledge construction scored 71% and specifically the fact that learners were able to work together with group members to accomplish learning tasks throughout the study of the course units (79%). Learners developed reports from activities (67%), submitted solutions to discussion questions (68%) and did critique peer arguments (69%). Generally, learners performed well in blended learning in the final examination with an average pass of 62% and standard deviation of 7.5.

Significant predictors of blended learning effectiveness ( RQ 2)

A standard multiple regression analysis was done taking learner characteristics/background and design features as predictor variables and learning outcomes as criterion variables. The data was first tested to check if it met the linear regression test assumptions and results showed the correlations between the independent variables and each of the dependent variables (highest 0.62 and lowest 0.22) as not being too high, which indicated that multicollinearity was not a problem in our model. From the coefficients table, the VIF values ranged from 1.0 to 2.4, well below the cut off value of 10 and indicating no possibility of multicollinearity. The normal probability plot was seen to lie as a reasonably straight diagonal from bottom left to top right indicating normality of our data. Linearity was found suitable from the scatter plot of the standardized residuals and was rectangular in distribution. Outliers were no cause for concern in our data since we had only 1% of all cases falling outside 3.0 thus proving the data as a normally distributed sample. Our R -square values was at 0.525 meaning that the independent variables explained about 53% of the variance in overall satisfaction, motivation and knowledge construction of the learners. All the models explaining the three dependent variables of learner satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and knowledge construction were significant at the 0.000 probability level (Table 6 ).

From the table above, design features (technology quality and online tools and resources), and learner characteristics (attitudes to blended learning, self-regulation) were significant predictors of learner satisfaction in blended learning. This means that good technology with the features involved and the learner positive attitudes with capacity to do blended learning with self drive led to their satisfaction. The design features (technology quality, interactions) and learner characteristics (self regulation and social support), were found to be significant predictors of learner knowledge construction. This implies that learners’ capacity to go on their work by themselves supported by peers and high levels of interaction using the quality technology led them to construct their own ideas in blended learning. Design features (technology quality, online tools and resources as well as learner interactions) and learner characteristics (self regulation), significantly predicted the learners’ intrinsic motivation in blended learning suggesting that good technology, tools and high interaction levels with independence in learning led to learners being highly motivated. Finally, none of the independent variables considered under this study were predictors of learning outcomes (grade).

In this study we have investigated learning outcomes as dependent variables to establish if particular learner characteristics/backgrounds and design features are related to the outcomes for blended learning effectiveness and if they predict learning outcomes in blended learning. We took students from three schools out of five and one directorate of post-graduate studies at a Ugandan University. The study suggests that the characteristics and design features examined are good drivers towards an effective blended learning environment though a few of them predicted learning outcomes in blended learning.

Student characteristics/background, blended learning design features and learning outcomes

The learner characteristics, design features investigated are potentially important for an effective blended learning environment. Performance by gender shows a balance with no statistical differences between male and female. There are statistically significant differences ( p < .005) in the performance between age groups with means of 62% for age group 20–30 and 67% for age group 31 –39. The indicators of self regulation exist as well as positive attitudes towards blended learning. Learners do well with word processing, e-mail, spreadsheets and web browsers but still lag below average in html tools. They show computer confidence at 75.3%; which gives prospects for an effective blended learning environment in regard to their computer competence and confidence. The levels of family and social support for learners stand at 61 and 75% respectively, indicating potential for blended learning to be effective. The learners’ balance between study and work is a drive factor towards blended learning effectiveness since their management of their workload vis a vis study time is at 60 and 61% of the learners are encouraged to go for study by their bosses. Learner satisfaction with the online system and its tools shows prospect for blended learning effectiveness but there are challenges in regard to locating course content and assignments, submitting their work and staying on a task during online study. Average collaborative, cognitive learning as well as learner-teacher interactions exist as important factors. Technology quality for effective blended learning is a potential for effectiveness though features like the blog and wiki are rarely used by learners. Face-to-face support is satisfactory and it should be conducted every month. There is high intrinsic motivation, satisfaction and knowledge construction as well as good performance in examinations ( M = 62%, SD = 7.5); which indicates potentiality for blended learning effectiveness.

Significant predictors of blended learning effectiveness

Among the design features, technology quality, online tools and face-to-face support are predictors of learner satisfaction while learner characteristics of self regulation and attitudes to blended learning are predictors of satisfaction. Technology quality and interactions are the only design features predicting learner knowledge construction, while social support, among the learner backgrounds, is a predictor of knowledge construction. Self regulation as a learner characteristic is a predictor of knowledge construction. Self regulation is the only learner characteristic predicting intrinsic motivation in blended learning while technology quality, online tools and interactions are the design features predicting intrinsic motivation. However, all the independent variables are not significant predictors of learning performance in blended learning.

The high computer competences and confidence is an antecedent factor for blended learning effectiveness as noted by Hadad ( 2007 ) and this study finds learners confident and competent enough for the effectiveness of blended learning. A lack in computer skills causes failure in e-learning and blended learning as noted by Shraim and Khlaif ( 2010 ). From our study findings, this is no threat for blended learning our case as noted by our results. Contrary to Cohen et al. ( 2012 ) findings that learners’ family responsibilities and hours of employment can impede their process of learning, it is not the case here since they are drivers to the blended learning process. Time conflict, as compounded by family, employment status and management support (Packham et al., 2004 ) were noted as causes of learner failure and drop out of online courses. Our results show, on the contrary, that these factors are drivers for blended learning effectiveness because learners have a good balance between work and study and are supported by bosses to study. In agreement with Selim ( 2007 ), learner positive attitudes towards e-and blended learning environments are success factors. In line with Coldwell et al. ( 2008 ), no statistically significant differences exist between age groups. We however note that Coldwel, et al dealt with young, middle-aged and old above 45 years whereas we dealt with young and middle aged only.

Learner interactions at all levels are good enough and contrary to Astleitner, ( 2000 ) that their absence makes learners withdraw, they are a drive factor here. In line with Loukis (2007) the LMS quality, reliability and ease of use lead to learning efficiency as technology quality, online tools are predictors of learner satisfaction and intrinsic motivation. Face-to-face sessions should continue on a monthly basis as noted here and is in agreement with Marriot et al. ( 2004 ) who noted learner preference for it for facilitating social interaction and communication skills. High learner intrinsic motivation leads to persistence in online courses as noted by Menager-Beeley, ( 2004 ) and is high enough in our study. This implies a possibility of an effectiveness blended learning environment. The causes of learner dissatisfaction noted by Islam ( 2014 ) such as incompetence in the use of the LMS are contrary to our results in our study, while the one noted by Hara and Kling, ( 2001 ) as resulting from technical difficulties and ambiguous course instruction are no threat from our findings. Student-teacher interaction showed a relation with satisfaction according to Swan ( 2001 ) but is not a predictor in our study. Initiating knowledge construction by learners for blended learning effectiveness is exhibited in our findings and agrees with Rahman, Yasin and Jusof ( 2011 ). Our study has not agreed with Eom et al. ( 2006 ) who found learner interactions as predictors of learner satisfaction but agrees with Naaj et al. ( 2012 ) regarding technology as a predictor of learner satisfaction.

Conclusion and recommendations

An effective blended learning environment is necessary in undertaking innovative pedagogical approaches through the use of technology in teaching and learning. An examination of learner characteristics/background, design features and learning outcomes as factors for effectiveness can help to inform the design of effective learning environments that involve face-to-face sessions and online aspects. Most of the student characteristics and blended learning design features dealt with in this study are important factors for blended learning effectiveness. None of the independent variables were identified as significant predictors of student performance. These gaps are open for further investigation in order to understand if they can be significant predictors of blended learning effectiveness in a similar or different learning setting.

In planning to design and implement blended learning, we are mindful of the implications raised by this study which is a planning evaluation research for the design and eventual implementation of blended learning. Universities should be mindful of the interplay between the learner characteristics, design features and learning outcomes which are indicators of blended learning effectiveness. From this research, learners manifest high potential to take on blended learning more especially in regard to learner self-regulation exhibited. Blended learning is meant to increase learners’ levels of knowledge construction in order to create analytical skills in them. Learner ability to assess and critically evaluate knowledge sources is hereby established in our findings. This can go a long way in producing skilled learners who can be innovative graduates enough to satisfy employment demands through creativity and innovativeness. Technology being less of a shock to students gives potential for blended learning design. Universities and other institutions of learning should continue to emphasize blended learning approaches through installation of learning management systems along with strong internet to enable effective learning through technology especially in the developing world.

Abubakar, D. & Adetimirin. (2015). Influence of computer literacy on post-graduates’ use of e-resources in Nigerian University Libraries. Library Philosophy and Practice. From http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/ . Retrieved 18 Aug 2015.

Ahmad, N., & Al-Khanjari, Z. (2011). Effect of Moodle on learning: An Oman perception. International Journal of Digital Information and Wireless Communications (IJDIWC), 1 (4), 746–752.

Google Scholar

Anderson, T. (2004). Theory and Practice of Online Learning . Canada: AU Press, Athabasca University.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2000). How classroom environment and student engagement affect learning in internet-basedMBAcourses. Business Communication Quarterly, 63 (4), 9–18.

Article Google Scholar

Askar, P. & Altun, A. (2008). Learner satisfaction on blended learning. E-Leader Krakow , 2008.

Astleitner, H. (2000) Dropout and distance education. A review of motivational and emotional strategies to reduce dropout in web-based distance education. In Neuwe Medien in Unterricht, Aus-und Weiterbildung Waxmann Munster, New York.

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M., Paton, V. O., & Lai, S. (2009). Measuring self regulation in online and blended learning environments’. Internet and Higher Education, 12 (1), 1–6.

Beard, L. A., Harper, C., & Riley, G. (2004). Online versus on-campus instruction: student attitudes & perceptions. TechTrends, 48 (6), 29–31.

Berenson, R., Boyles, G., & Weaver, A. (2008). Emotional intelligence as a predictor for success in online learning. International Review of Research in open & Distance Learning, 9 (2), 1–16.

Blocker, J. M., & Tucker, G. (2001). Using constructivist principles in designing and integrating online collaborative interactions. In F. Fuller & R. McBride (Eds.), Distance education. Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 32–36). ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 457 822.

Cohen, K. E., Stage, F. K., Hammack, F. M., & Marcus, A. (2012). Persistence of master’s students in the United States: Developing and testing of a conceptual model . USA: PhD Dissertation, New York University.

Coldwell, J., Craig, A., Paterson, T., & Mustard, J. (2008). Online students: Relationships between participation, demographics and academic performance. The Electronic Journal of e-learning, 6 (1), 19–30.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1982). Intrinsic Motivation Inventory. Available from selfdeterminationtheory.org/intrinsic-motivation-inventory/ . Accessed 2 Aug 2016.

Delone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The Delone and McLean model of information systems success: A Ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19 (4), 9–30.

Demirkol, M., & Kazu, I. Y. (2014). Effect of blended environment model on high school students’ academic achievement. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 13 (1), 78–87.

Eom, S., Wen, H., & Ashill, N. (2006). The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in university online education: an empirical investigation’. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4 (2), 215–235.

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 7 (2), 95–105.

Goyal, E., & Tambe, S. (2015). Effectiveness of Moodle-enabled blended learning in private Indian Business School teaching NICHE programs. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 5 (2), 14–22.

Green, J., Nelson, G., Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. (2006). The causal ordering of self-concept and academic motivation and its effect on academic achievement. International Education Journal, 7 (4), 534–546.

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating Professional Development . Thousands Oaks: Corwin Press.

Hadad, W. (2007). ICT-in-education toolkit reference handbook . InfoDev. from http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.301.html . Retrieved 04 Aug 2015.

Hara, N. & Kling, R. (2001). Student distress in web-based distance education. Educause Quarterly. 3 (2001).

Heinich, R., Molenda, M., Russell, J. D., & Smaldino, S. E. (2001). Instructional Media and Technologies for Learning (7th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Hofmann, J. (2014). Solutions to the top 10 challenges of blended learning. Top 10 challenges of blended learning. Available on cedma-europe.org .

Islam, A. K. M. N. (2014). Sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction with a learning management system in post-adoption stage: A critical incident technique approach. Computers in Human Behaviour, 30 , 249–261.

Kelley, D. H. & Gorham, J. (2009) Effects of immediacy on recall of information. Communication Education, 37 (3), 198–207.

Kenney, J., & Newcombe, E. (2011). Adopting a blended learning approach: Challenges, encountered and lessons learned in an action research study. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 15 (1), 45–57.

Kintu, M. J., & Zhu, C. (2016). Student characteristics and learning outcomes in a blended learning environment intervention in a Ugandan University. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 14 (3), 181–195.

Kuo, Y., Walker, A. E., Belland, B. R., & Schroder, L. E. E. (2013). A predictive study of student satisfaction in online education programs. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14 (1), 16–39.

Kwak, D. W., Menezes, F. M., & Sherwood, C. (2013). Assessing the impact of blended learning on student performance. Educational Technology & Society, 15 (1), 127–136.

Lim, D. H., & Kim, H. J. (2003). Motivation and learner characteristics affecting online learning and learning application. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 31 (4), 423–439.

Lim, D. H., & Morris, M. L. (2009). Learner and instructional factors influencing learner outcomes within a blended learning environment. Educational Technology & Society, 12 (4), 282–293.

Lin, B., & Vassar, J. A. (2009). Determinants for success in online learning communities. International Journal of Web-based Communities, 5 (3), 340–350.

Loukis, E., Georgiou, S. & Pazalo, K. (2007). A value flow model for the evaluation of an e-learning service. ECIS, 2007 Proceedings, paper 175.

Lynch, R., & Dembo, M. (2004). The relationship between self regulation and online learning in a blended learning context. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 5 (2), 1–16.

Marriot, N., Marriot, P., & Selwyn. (2004). Accounting undergraduates’ changing use of ICT and their views on using the internet in higher education-A Research note. Accounting Education, 13 (4), 117–130.

Menager-Beeley, R. (2004). Web-based distance learning in a community college: The influence of task values on task choice, retention and commitment. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California). Dissertation Abstracts International, 64 (9-A), 3191.

Naaj, M. A., Nachouki, M., & Ankit, A. (2012). Evaluating student satisfaction with blended learning in a gender-segregated environment. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 11 , 185–200.

Nurmela, K., Palonen, T., Lehtinen, E. & Hakkarainen, K. (2003). Developing tools for analysing CSCL process. In Wasson, B. Ludvigsen, S. & Hoppe, V. (eds), Designing for change in networked learning environments (pp 333–342). Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Kluwer.

Osgerby, J. (2013). Students’ perceptions of the introduction of a blended learning environment: An exploratory case study. Accounting Education, 22 (1), 85–99.

Oxford Group, (2013). Blended learning-current use, challenges and best practices. From http://www.kineo.com/m/0/blended-learning-report-202013.pdf . Accessed on 17 Mar 2016.

Packham, G., Jones, P., Miller, C., & Thomas, B. (2004). E-learning and retention key factors influencing student withdrawal. Education and Training, 46 (6–7), 335–342.

Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS Survival Mannual (4th ed.). Maidenhead: OUP McGraw-Hill.

Park, J.-H., & Choi, H. J. (2009). Factors influencing adult learners’ decision to drop out or persist in online learning. Educational Technology & Society, 12 (4), 207–217.

Picciano, A., & Seaman, J. (2007). K-12 online learning: A survey of U.S. school district administrators . New York, USA: Sloan-C.

Piccoli, G., Ahmad, R., & Ives, B. (2001). Web-based virtual learning environments: a research framework and a preliminary assessment of effectiveness in basic IT skill training. MIS Quarterly, 25 (4), 401–426.

Pituch, K. A., & Lee, Y. K. (2006). The influence of system characteristics on e-learning use. Computers & Education, 47 (2), 222–244.

Rahman, S. et al, (2011). Knowledge construction process in online learning. Middle East Journal of Scientific Research, 8 (2), 488–492.

Rovai, A. P. (2003). In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. Computers & Education, 6 (1), 1–16.

Sankaran, S., & Bui, T. (2001). Impact of learning strategies and motivation on performance: A study in Web-based instruction. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 28 (3), 191–198.

Selim, H. M. (2007). Critical success factors for e-learning acceptance: Confirmatory factor models. Computers & Education, 49 (2), 396–413.

Shraim, K., & Khlaif, Z. N. (2010). An e-learning approach to secondary education in Palestine: opportunities and challenges. Information Technology for Development, 16 (3), 159–173.

Shrain, K. (2012). Moving towards e-learning paradigm: Readiness of higher education instructors in Palestine. International Journal on E-Learning, 11 (4), 441–463.

Song, L., Singleton, E. S., Hill, J. R., & Koh, M. H. (2004). Improving online learning: student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics’. Internet and Higher Education, 7 (1), 59–70.

Stacey, E., & Gerbic, P. (2007). Teaching for blended learning: research perspectives from on-campus and distance students. Education and Information Technologies, 12 , 165–174.

Swan, K. (2001). Virtual interactivity: design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Education, 22 (2), 306–331.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Thompson, E. (2004). Distance education drop-out: What can we do? In R. Pospisil & L. Willcoxson (Eds.), Learning Through Teaching (Proceedings of the 6th Annual Teaching Learning Forum, pp. 324–332). Perth, Australia: Murdoch University.

Tselios, N., Daskalakis, S., & Papadopoulou, M. (2011). Assessing the acceptance of a blended learning university course. Educational Technology & Society, 14 (2), 224–235.

Willging, P. A., & Johnson, S. D. (2009). Factors that influence students’ decision to drop-out of online courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13 (3), 115–127.

Zhu, C. (2012). Student satisfaction, performance and knowledge construction in online collaborative learning. Educational Technology & Society, 15 (1), 127–137.

Zielinski, D. (2000). Can you keep learners online? Training, 37 (3), 64–75.

Download references

Authors’ contribution

MJK conceived the study idea, developed the conceptual framework, collected the data, analyzed it and wrote the article. CZ gave the technical advice concerning the write-up and advised on relevant corrections to be made before final submission. EK did the proof-reading of the article as well as language editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mountains of the Moon University, P.O. Box 837, Fort Portal, Uganda

Mugenyi Justice Kintu & Edmond Kagambe

Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, Brussels, 1050, Ixelles, Belgium

Mugenyi Justice Kintu & Chang Zhu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mugenyi Justice Kintu .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kintu, M.J., Zhu, C. & Kagambe, E. Blended learning effectiveness: the relationship between student characteristics, design features and outcomes. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14 , 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0043-4

Download citation

Received : 13 July 2016

Accepted : 23 November 2016

Published : 06 February 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0043-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Blended learning effectiveness

- Learner characteristics

- Design features

- Learning outcomes and significant predictors

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychol Res Behav Manag

A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on Blended Learning: Trends, Gaps and Future Directions

Muhammad azeem ashraf.

1 Research Institute of Education Science, Hunan University, Changsha, People’s Republic of China

Meijia Yang

Yufeng zhang, mouna denden.

2 Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE), Tunis Higher School of Engineering (ENSIT), Tunis, Tunisia

Ahmed Tlili

3 Smart Learning Institute, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

4 School of Professional Studies, Columbia University, New York City, NY, USA

Ronghuai Huang

Daniel burgos.

5 Research Institute for Innovation & Technology in Education (UNIR iTED), Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR), Logroño, 26006, Spain

Blended Learning (BL) is one of the most used methods in education to promote active learning and enhance students’ learning outcomes. Although BL has existed for over a decade, there are still several challenges associated with it. For instance, the teachers’ and students’ individual differences, such as their behaviors and attitudes, might impact their adoption of BL. These challenges are further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as schools and universities had to combine both online and offline courses to keep up with health regulations. This study conducts a systematic review of systematic reviews on BL, based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, to identify BL trends, gaps and future directions. The obtained findings highlight that BL was mostly investigated in higher education and targeted students in the first place. Additionally, most of the BL research is coming from developed countries, calling for cross-collaborations to facilitate BL adoption in developing countries in particular. Furthermore, a lack of ICT skills and infrastructure are the most encountered challenges by teachers, students and institutions. The findings of this study can create a roadmap to facilitate the adoption of BL. The findings of this study could facilitate the design and adoption of BL which is one of the possible solutions to face major health challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Blended Learning (BL) is one of the most frequently used approaches related to the application of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in education. 1 In its simplest definition, BL aims to combine face-to-face (F2F) and online settings, resulting in better learning engagement and flexible learning experiences, with rich settings way further the use of a simple online content repository to support the face-to-face classes. 2 , 3 Researchers and practitioners have used different terms to refer to the blended learning approach, including “brick and click” instruction, 4 hybrid learning, 4 dual-mode instruction, 5 blended pedagogies, 4 HyFlex learning, 6 targeted learning, 4 multimodal learning and flipped learning. 3

Researchers and practitioners have pointed out that designing BL experiences could be complex, as several features need to be considered, including the quality of learning experiences, learning instruction, learning technologies/tools and applied pedagogies. 7–9 Therefore, they have focused on investigating different BL perspectives since 2000. 10 Despite this 21-year investigation and research, there are still several challenges and unanswered questions related to BL, including the quality of the designed learning materials 9 , 11 , 12 applied learning instructions, 9 the culture of resisting this approach, 13 , 14 and teachers being overloaded when applying BL. 15 The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the challenges associated with BL. Specifically, international universities and schools worldwide had to take several actions with respect to health regulations, such as reducing classroom sizes. 16 Therefore, they combined online and offline learning to maintain their courses for both on-campus and off-campus experiences. 16 For instance, as a response to the effort made by the government of Indonesia to carry out physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, in all domains including education, some elementary schools used BL with Moodle platform to ensure the continuity of learning. 17 In this context, several teachers raised concerns about implementing BL experiences, such as the lack of infrastructure and competencies to do so, calling for further investigation in this regard. Several international organizations, such as UNESCO and ILO, claimed that teacher professional development for online and blended learning is one of the priorities for building resilient education systems for the future. 18

Based on the background above, it is seen that there is still room for discussion of designing and implementing effective BL. Researchers have suggested that conducting literature reviews can help identify challenges and solutions in a given domain. 19–21 Review papers may serve the development of new theories and also shape future research studies, as well as disseminate knowledge to promote scientific discussion and reflection about concepts, methods and practices. However, several BL systematic reviews were conducted in the literature which are of variable quality, focus and geographical region. This made the BL literature fragmented, where no study provides a comprehensive summary that could be a reference for different stakeholders to adopt BL. In this context, Smith et al mentioned that a logical and appropriate next step is to conduct a systematic review of reviews of the topic under consideration, allowing the findings of separate reviews to be compared and contrasted, thereby providing comprehensive and in-depth findings for different stakeholders. 22 As BL is becoming the new normal, 23 this study takes a step further beyond simply conducting a systematic review and conducts a systematic review of systematic reviews on BL. By systematically examining high-quality published literature review articles, this study reveals the reported BL trends and challenges, as well as research gaps and future paths. These findings could help different stakeholders (eg, policy makers, teachers, instructional designers, etc.) to facilitate the design and adoption of BL worldwide. Although several systematic reviews of literature reviews have been conducted in different fields, such as engineering, 24 healthcare 25 and tourism, 26 no one was conducted on blended learning, to the best of our knowledge. It should be noted that one study was conducted in this context, but it mainly focused on the transparency of the systematic reviews that were conducted 27 and was not about the BL field itself.

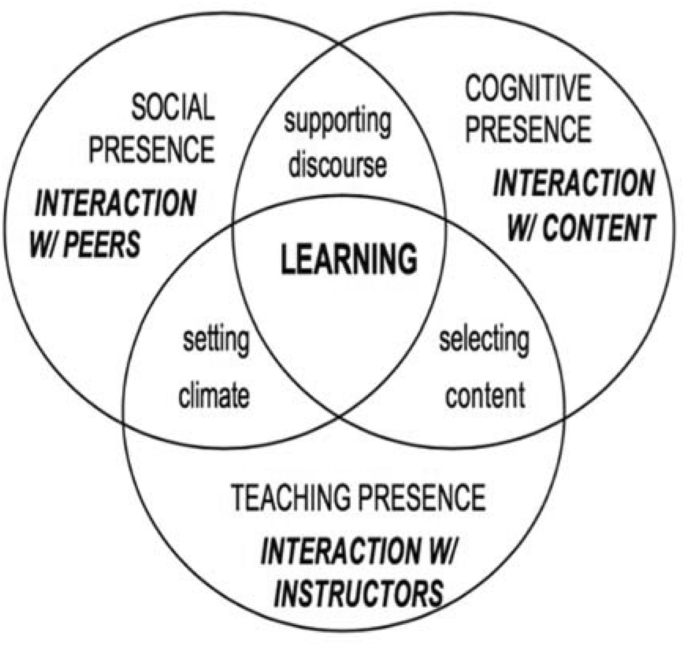

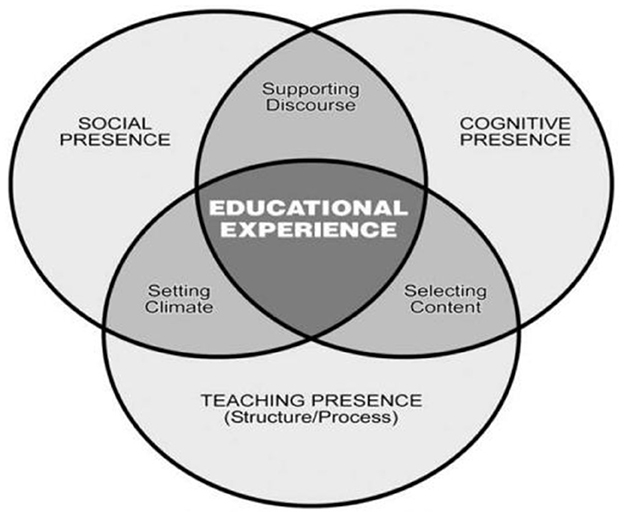

Guided by the technology-based learning model (see Figure 1 ), this study aims to answer the following six research questions:

Blended learning model.

RQ1. What are the trends of blended learning research in terms of: publication year, geographic region and publication venue?

RQ2. What are the covered subject areas in blended learning research?

RQ3. Who are the covered participants (stakeholders) in blended learning research?

RQ4. What are the most frequently used research methods (in systematic reviews) in blended learning research?

RQ5. How blended learning was designed in terms of the used learning models and technologies?

RQ6. What are the learning outcomes of blended learning, as well as the associated challenges?

The findings of this study could help to analyze the behaviors and attitudes of different stakeholders from different BL contexts, hence draw a comprehensive understanding of BL and its impact from different international perspectives. This can promote cross-country collaboration and more open BL design that more worldwide universities could be involved in. The findings could also facilitate the design (eg, in terms of the used learning models and technologies) and adoption of BL which is one of the possible solutions to face major health challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This study presents a systematic review of systematic review papers on BL. In particular, this review follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. 28 PRISMA provides a standard peer-accepted methodology that uses a guideline checklist, which was strictly followed for this study, to contribute to the quality assurance of the revision process and to ensure its replicability. A review protocol was developed, describing the search strategy and article selection criteria, quality assessment, data extraction and data analysis procedures.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

To deal with this topic, an extensive search for research articles was undertaken in the most common and highly valued electronic databases: Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar, 29 using the following search strings.

Search string: ((blending learning substring) AND (literature review substring))

Blended learning substring: “Blended learning” OR “blended education” OR “hybrid learning” OR “flipped classroom” OR “flipped learning” OR “inverted classroom” OR “mixed-mode instruction” OR “HyFlex learning”

Literature review substring: “Review” OR “Systematic review” OR “state-of-art” OR “state of the art” OR “state of art” OR “meta-analysis” OR “meta analytic study” OR “mapping stud*” OR “overview”

Databases were searched separately by two of the authors. After searching the relevant databases, the two authors independently analyzed the retrieved papers by titles and abstracts, and papers that clearly were not systematic reviews, such as empirical, descriptive and conceptual papers, were excluded. Then, the two authors independently performed an eligibility assessment by carefully screening the full texts of the remaining papers, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in Table 1 . During this phase, disagreements between the authors were resolved by discussion or arbitration from a third author. Specifically, to provide high-quality papers, this study was restricted to papers published in journals.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This research yielded a total of 972 articles. After removing duplicated papers, 816 papers remained. 672 papers were then removed based on the screening of titles and abstracts. The remaining 144 papers were considered and assessed as full texts. 85 of these papers did not pass the inclusion criteria. Thus, as a total number, 57 eligible research studies remained for inclusion in the systematic review. Figure 2 presents the study selection process as recommended by the PRISMA group. 28

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

Quality Assessment

For methodological quality evaluation, the AMSTAR assessment tool was used. AMSTAR is widely used as a valuable tool to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews conducted in any academic field. 30 It consists of 11 items that evaluate whether the review was guided by a protocol, whether there was duplicate study selection and data extraction, the comprehensiveness of the search, the inclusion of grey literature, the use of quality assessment, the appropriateness of data synthesis and the documentation of conflicts of interest. Specifically, two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included reviews using the AMSTAR checklist. Items were evaluated as “Yes” (meaning the item has been properly handled, 1 point), “No” (indicating the possibility that the item did not perform well, 0 points) or “Not applicable” (in the case of performance failure because the item was not applied, 0 points). Disagreements regarding the AMSTAR score were resolved by discussion or by a decision made by a third author.