- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2020

Experiences of loneliness: a study protocol for a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature

- Phoebe E. McKenna-Plumley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5627-5730 1 ,

- Jenny M. Groarke 1 ,

- Rhiannon N. Turner 1 &

- Keming Yang 2

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 284 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

5568 Accesses

7 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Loneliness is a highly prevalent, harmful, and aversive experience which is fundamentally subjective: social isolation alone cannot account for loneliness, and people can experience loneliness even with ample social connections. A number of studies have qualitatively explored experiences of loneliness; however, the research lacks a comprehensive overview of these experiences. We present a protocol for a study that will, for the first time, systematically review and synthesise the qualitative literature on experiences of loneliness in people of all ages from the general, non-clinical population. The aim is to offer a fine-grained look at experiences of loneliness across the lifespan.

We will search multiple electronic databases from their inception onwards: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, Sociological Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, CINAHL, and the Education Resource Information Center. Sources of grey literature will also be searched. We will include empirical studies published in English including any qualitative study design (e.g. interview, focus group). Studies should focus on individuals from non-clinical populations of any age who describe experiences of loneliness. All citations, abstracts, and full-text articles will be screened by one author with a second author ensuring consistency regarding inclusion. Potential conflicts will be resolved through discussion. Thematic synthesis will be used to synthesise this literature, and study quality will be assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research. The planned review will be reported according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement.

The growing body of research on loneliness predictors, outcomes, and interventions must be grounded in an understanding of the lived experience of loneliness. This systematic review and thematic synthesis will clarify how loneliness is subjectively experienced across the lifespan in the general population. This will allow for a more holistic understanding of the lived experience of loneliness which can inform clinicians, researchers, and policymakers working in this important area.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42020178105 .

Peer Review reports

Loneliness has become the focus of a wealth of research in recent years. This attention is well placed given that loneliness has been designated as a significant public health issue in the UK [ 1 ] and is associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] and an increase in risk of death similar to that of smoking [ 6 ]. In light of this, it is concerning that recent research has found that loneliness is highly prevalent across age groups, with young people (under 25 years) and older adults (over 65 years) indicating the highest levels [ 7 , 8 ].

Whilst an ever-increasing body of research is situating loneliness at its centre, there is relatively little work which focuses on the lived experience of loneliness: how loneliness feels and what makes up experiences of loneliness. Phenomena that might appear to describe loneliness, such as social isolation, are distinct from the actual experience of it. Whilst loneliness is generally characterised as the distress one experiences when they perceive their social connections to be lacking in number or quality, social isolation is the objective limitation or absence of connections [ 9 ]. Social isolation does not necessarily beget loneliness, and indeed, Hawkley and Cacioppo [ 3 ] remark on how humans can perceive meaningful social relationships where none objectifiably exist, such as with God, or where reciprocity is not possible, such as with fictional characters. Whilst associations between aloneness and loneliness have been richly demonstrated [ 10 , 11 ], other research has found moderate and low correlations between social isolation and loneliness [ 12 , 13 ]. These findings underline the need to better understand what makes up the subjective experience of loneliness, given that it is clearly not sufficiently captured by the objective experience of being alone. Given the subjective nature of the phenomenon, qualitative methods are particularly suited to research into experiences of loneliness, as they can aim to capture the idiosyncrasies of these experiences.

A number of qualitative studies of loneliness experiences have been carried out. In perhaps the largest study of its type, Rokach [ 14 ] analysed written accounts of 526 adults’ loneliest experience, specifically asking about their thoughts, feelings, and coping strategies. This generated a model with four major elements (self-alienation, interpersonal isolation, distressed reactions, and agony) and twenty-three components such as emptiness, numbness, and missing a specific person or relationship. Although this study offered impressive scale, the vast majority of participants were between 19 and 45 years old, and as a result, the model may underestimate factors experienced across the lifespan. The findings might be usefully integrated with more recent research which qualitatively explores loneliness in other age groups (e.g. [ 15 ]). Harmonising this research by looking closely at how people describe their experiences of loneliness and working from the bottom-up to create a fine-grained view of what makes up these experiences will provide a more holistic understanding of loneliness and how it might best be defined and ameliorated.

There are a number of available definitions of loneliness offered by researchers. The widely accepted description from Perlman and Peplau [ 16 ], for example, states that loneliness is an unpleasant and distressing subjective phenomenon arising when one’s desired level of social relations differs from their actual level. However, research lacks an overarching subjective perspective, by which we mean a description of loneliness which is grounded in accounts of people’s lived experiences. This is a significant gap in the field given that loneliness is, by its nature, a subjective experience. Unlike objective phenomena like blood pressure or age, loneliness can only be definitively measured by asking a person whether they feel lonely. Weiss [ 17 ] argued that whilst available definitions of loneliness may be helpful, they do not sufficiently reflect the real phenomenon of loneliness because they define it in terms of its potential causes rather than the actual experience of being lonely. As such, studies which begin from definitions of loneliness like these may obscure the ways in which it is actually experienced and fail to capture the components and idiosyncrasies of these experiences.

A recent systematic review report [ 18 ] has explored the conceptualisations of loneliness employed in qualitative research, finding that loneliness tended to be defined as social, emotional, or existential types. However, the review covered only studies of adults (16 years and up), including heterogenous clinical populations (e.g. people receiving cancer treatment, people living with specific mental health conditions, and people on long-term sick leave), and placed central importance on the concepts, models, theories, and frameworks of loneliness utilised in research. Studies which did not employ an identified concept, model, framework, or theory of loneliness were excluded. Moreover, rather than synthesising how people describe their loneliness, the authors aimed to assess how research conceptualises loneliness across the adult life course. This leaves a gap with respect to how research participants specifically describe their lived experiences of loneliness, rather than how researchers might conceptualise it. Achterberg and colleagues [ 19 ] recently conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on experiences of loneliness in young people with depression. As the findings are specific to experiences in this population, they may not reflect those of wider age groups or individuals who do not have depression. Kitzmüller and colleagues [ 20 ] used meta-ethnography to synthesise studies regarding experiences and ways of dealing with loneliness in older adults (60 years and older). However, they synthesised only articles from health care disciplines published in scientific journals from 2001 to 2016 and included studies on clinical populations, such as older women with multiple chronic conditions. Moreover, there has been an increase in research output regarding loneliness in recent years, and relevant studies may have been published since this review was conducted (e.g. [ 15 ]). To the authors’ knowledge, the systematic review report on conceptual frameworks used in loneliness research [ 18 ], the meta-synthesis of loneliness in young people with depression [ 19 ], and the meta-ethnography of older adults’ loneliness [ 20 ] are the only such systematic reviews of qualitative literature regarding experiences of loneliness to date. The current systematic review will instead take a bottom-up approach which focuses on non-clinical populations of all ages to synthesise findings on participants’ experiences of loneliness, rather than the conceptualisations that might be imposed by study authors. This will fill a gap in the literature by synthesising the qualitative evidence focusing on experiences of loneliness across the lifespan. This inductive synthesis of the available subjective descriptions of loneliness will offer a nuanced view of loneliness experiences. It is imperative for research and practice that we deepen the current understanding of these experiences to inform how we approach describing, researching, and attempting to ameliorate loneliness.

The proposed research aims to offer a holistic view of the experience of loneliness across the lifespan through a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature focusing on these experiences. To address this aim, there is one central research question: How do people describe their experiences of loneliness?

This research question concerns aspects of loneliness which participants discuss when describing their lived experiences. Whilst we expect that this would concern emotional, social, and cognitive components of the experience, we understand that these findings may also come to reflect perceived causes or effects of loneliness.

This review will also consider the age groups that have been studied and how experiences of loneliness might vary across the different age groups examined in this literature. Loneliness research is often weighted towards investigations of older adults, despite the fact that the prevalence of loneliness is high across the lifespan; recent UK research found a prevalence of 40% in 16- to 24-year-olds and 27% in people over 75 [ 7 ]. This review will also shed light on the age groups that have been included in qualitative research on loneliness experiences. In doing so, this research may identify age groups which have been understudied and may be underrepresented in this field of research, potentially pointing to life stages where experiences of loneliness might be usefully explored in more detail in the future.

Furthermore, given the relatively small number of qualitative studies into the experience of loneliness compared with quantitative research in this area, this review will also consider the reasons that study authors may offer for the relative shortage of qualitative work. This is an important point given that the review will inherently be constrained by the number of studies that exist and the focus that has primarily been given to quantitative loneliness research thus far.

Protocol registration and reporting

The review protocol has been registered within the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database from the University of York (registration number: CRD42020178105). This review protocol is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [ 21 ] (see checklist in Additional file 1 ). The proposed systematic review will be reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement [ 22 ]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 23 ] will inform the process of completing and reporting this planned review.

Eligibility criteria

Due to its suitability for qualitative evidence synthesis, the SPIDER tool [ 24 ] was used to assist in defining the research question and eligibility criteria in line with the following criteria: Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type (see Table 1 for details of these criteria). The exclusion criteria are as follows:

Studies not meeting the inclusion criteria described in Table 1

Studies not published in English

Studies with no qualitative component

Studies of clinical populations

Studies which report solely on objective phenomena such as social isolation rather than the subjectively perceived experience of loneliness

Studies in which the primary focus or one of the primary focuses is not experiences of loneliness

Papers will be deemed to focus sufficiently on experiences of loneliness if studying these experiences is a key aspect of the work rather than simply a part of the output. Accordingly, studies will only be included if authors state a relevant aim, objective, or research question related to investigating experiences of loneliness (i.e. to study experiences of loneliness) or if loneliness experiences are clearly explored and described (e.g. relevant questions are present in an appended interview guide). At the title and abstract screening stage, at least one relevant sentence or information that indicates likely relevance must be present for inclusion. The decision to exclude articles which do not primarily or equally focus on these experiences was made in order to gather meaningful data about loneliness experiences specifically and to capture experiences identified as loneliness by participants as much as possible, rather than related phenomena which may be grouped and labelled retrospectively as loneliness by researchers.

Information sources and search strategy

The primary source of literature will be a structured search of multiple electronic databases (from inception onwards): PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, Sociological Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), CINAHL, and the Education Resource Information Center (ERIC). The secondary source of potentially relevant material will be a search of the grey or difficult-to-locate literature using Google Scholar. In line with the guidance from Haddaway and colleagues [ 25 ] on using Google Scholar for systematic review, a title-only search using the same search terms will be conducted and the first 1000 results will be screened for eligibility. These searches will be supplemented with hand-searching in reference lists, such that the titles of all articles cited within eligible studies will be checked. When eligibility is unclear from the title, abstracts and full-texts will be checked until eligibility or ineligibility can be ascertained. This process will be repeated with any articles that are found to be eligible at this stage until no new eligible articles are found. Systematic reviews on similar topics will also be searched for potentially eligible studies. Grey literature will be located through searches of Google Scholar, opengrey.eu, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and websites of specific loneliness organisations such as the Campaign to End Loneliness, managed in collaboration with an information specialist. Efforts will be made to contact authors of completed, ongoing, and in-press studies for information regarding additional studies or relevant material.

The search strategy for our primary database (MEDLINE) was developed in collaboration with an information specialist. In collaboration with a specialist, the strategy will be translated for all of the databases. The search strategy has been peer reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [ 26 ]. Strategies will utilise keywords for loneliness and qualitative studies. A draft search strategy for MEDLINE is provided in Additional file 2 . Qualitative search terms were supplemented with relevant and useful subject headings and free-text terms from the Pearl Harvesting Search Framework synonym ring for qualitative research [ 27 ]. The inclusion of search terms related to social isolation specifically and related terms (e.g. “social engagement”) was considered and tested extensively through scoping searches and discussion with an information specialist. Adding these terms (and others such as “Patient Isolation” and “Quarantine”) did not appear to add unique papers that would be included above and beyond subject heading and free-text searching for “Loneliness”. Given the aim to include studies focused on experiences of loneliness specifically, this search strategy was deemed most appropriate. A similar strategy has been employed in other recent systematic review work focusing on loneliness (e.g. [ 28 , 29 ]). Moreover, test searches employing the search strategy retrieved all of seven informally identified likely eligible articles indexed in Scopus, indicating good sensitivity of the strategy. A free-text search to capture “perceived social isolation” was included as this specific term is used by some authors as a direct synonym for loneliness. The completed PRESS checklist is provided in Additional file 3 .

Data collection and analysis

Study selection.

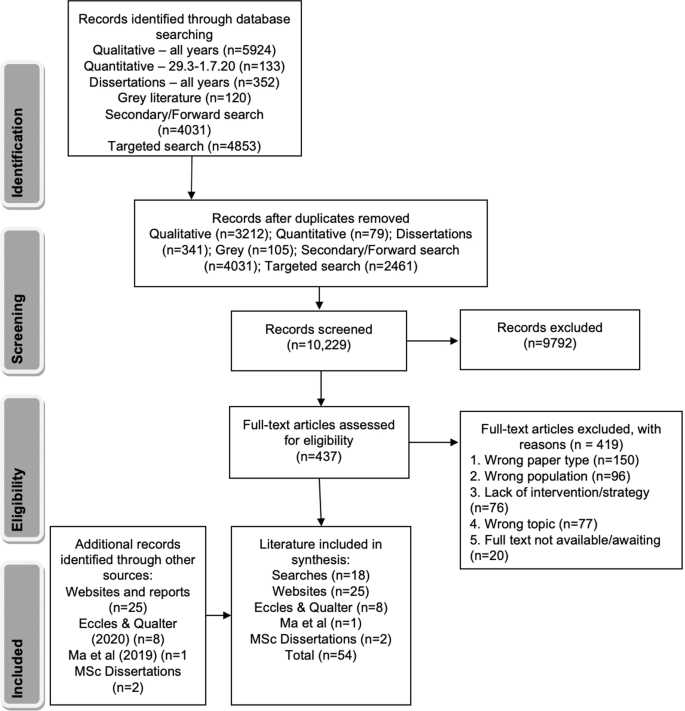

Firstly, the main review author (PMP) will perform the database search and hand-searching and will screen all titles to remove studies which are clearly not relevant. PMP will also undertake abstract screening to exclude any which are found to be irrelevant or inapplicable to the inclusion criteria. A second author (JG) will independently screen 50% of the titles and abstracts. Finally, full-text versions of the remaining articles will be read by PMP to assess whether they are suitable for inclusion in the final review. JG will independently review 50% of these full texts. In cases of disagreement, the two reviewers will discuss the study to reach a decision about inclusion or exclusion. In case agreement cannot be reached after discussion between the two reviewers, a third reviewer will be invited to reconcile their disagreement and make a final decision. The reason for the exclusion at the full-text stage will be recorded. After this screening process, the remaining articles will be included in the review following data extraction, quality appraisal, and analysis. The PRISMA statement will be followed to create a flowchart of the number of studies included and excluded at each stage of this process.

Data management

The articles to be screened will be managed in EndNoteX9, with subsequent EndNote databases used to manage each stage of the screening process.

Data extraction

Data will be extracted from the studies by PMP using a purpose-designed and piloted Microsoft Excel form. Information on author, publication year, geographic location of study, methodological approach, method, population, participant demographics, and main findings will be extracted to understand the basis of each study. JG will check this extracted data for accuracy.

For the thematic synthesis, in line with Thomas and Harden [ 30 ], all text labelled as “results” or “findings” will be extracted and entered into the NVivo software for analysis. This will be done because many factors, including varied reporting styles and misrepresentation of data as findings, can make it difficult to identify the findings in qualitative research [ 31 ]; accordingly, a wide-ranging approach will be used to capture as much relevant data as possible from each included article. The aim is to extract all data in which experiences of loneliness are described.

Quality appraisal

Quality of the included articles will be assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [ 32 ]. This quality will be considered during the development of the data synthesis. Different authors hold different viewpoints about inclusion versus exclusion of low-quality studies. However, given that they may still add important, authentic accounts of phenomena that have simply been reported inadequately [ 33 ], it is common to include lower-quality studies and consider quality during the synthesis process rather than excluding on the basis of it. Accordingly, this approach will be used in the present research.

Data synthesis

There are various accepted approaches to reviewing and synthesising qualitative research, including meta-ethnography [ 34 ], meta-synthesis [ 35 ], and narrative synthesis [ 36 ]. The current systematic review will utilise thematic synthesis as a methodology to create an overarching understanding of the experiences of loneliness described across studies. In thematic synthesis, descriptive themes which remain close to the primary studies are developed. Next, a new stage of analytical theme development is undertaken wherein the reviewer “goes beyond” the interpretations of the primary studies and develops higher-order constructs or explanations based on these descriptive themes [ 30 ]. The process of thematic synthesis for reviewing is similar to that of grounded theory for primary data, in that a translation and interpretative account of the phenomena of interest is produced. Thematic synthesis has been used to synthesise research on the experience of fatigue in neurological patients with multiple sclerosis [ 37 ], children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [ 38 ], and parents’ experiences of parenting a child with chronic illness [ 39 ]. This use of thematic synthesis to consider subjective experiences (rather than, for example, attitudes or motivations) melds well with the present research, which also sets its focus on a subjective experience.

As well as its successful application in similar systematic reviews, thematic synthesis was selected based on its appropriateness to the research question, time frame, resources, expertise, purpose, and potential type of data in line with the RETREAT framework for selecting an approach to qualitative evidence synthesis [ 40 ]. The RETREAT framework considers thematic synthesis to be appropriate for relatively rapid approaches which can be sustained by researchers with primary qualitative experience, unlike approaches such as meta-ethnography in which a researcher with specific familiarity with the method is needed. This is appropriate to the project time frame and background of this research team. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual [ 41 ] also notes that thematic synthesis is useful when considering shared elements across studies which are otherwise heterogenous, which is likely to be the case in this review given that the common factor (experiences of loneliness) may be present across studies with otherwise diverse populations and methodologies.

Guidance from Thomas and Harden [ 30 ] will be followed to synthesise the data. Firstly, the extracted text will be inductively coded line-by-line according to content and meaning. This inductive creation of codes should allow the content and meaning of each sentence to be captured. Multiple codes may be applied to the same sentence, and codes may be “free” or structured in a tree formation at this stage. Before moving forward, all text referred to by each code will be rechecked to ensure consistency in what is considered a single code or whether more levels of coding are required.

After this stage, similarities and differences between the codes will be examined, and they will begin to be organised into a hierarchy of groups of codes. New codes will be applied to these groups to describe their overall meaning. This will create a tree structure of descriptive themes which should not deviate largely from the original study findings; rather, findings will have been integrated into an organised whole. At this stage, the synthesis should remain close to the findings of the included studies.

At the final stage of analysis, higher-order analytical themes may be inferred from the descriptive themes which will offer a theoretical structure for experiences of loneliness. This inferential process will be carried out through collaboration between the research team (primarily PMP and JG).

Sensitivity analysis

After the synthesis is complete, a sensitivity analysis will be undertaken in which any low-quality studies (as identified through the JBI checklist) are excluded from the analysis to assess whether the synthesis is altered when these studies are removed, in terms of any themes being lost entirely or becoming less rich or thick [ 42 ]. Sensitivity analysis will also be used to assess whether any age group is entirely responsible for a given theme. In this way, the robustness of the synthesis can be appraised and the individual findings can remain grounded in their context whilst also extending into a broader understanding of the experiences of loneliness.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Risk of bias in individual studies will be taken into account through utilisation of the JBI checklist, which includes ten questions to assess whether a study is adequately conceptualised and reported [ 32 ]. PMP will use the checklist to assess the quality of each study. Whilst all eligible studies will be included in the synthesis (as described in the “Quality appraisal” section), any lower-quality studies will be excluded during post-synthesis sensitivity analysis in order to assess whether their inclusion has affected the synthesis in any way as suggested by Carroll and Booth [ 43 ].

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation – Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) approach [ 44 , 45 ] will be used to assess how much confidence can be placed in the findings of this qualitative evidence synthesis. This will allow a transparent, systematic appraisal of confidence in the findings for researchers, clinicians, and other decision-makers who may utilise the evidence from the planned systematic review. GRADE-CERQual involves assessment in four domains: (1) methodological limitations, (2) coherence, (3) adequacy of data, and (4) relevance. There is also an overall rating of confidence: high, moderate, low, or very low. These findings will be displayed in a Summary of Qualitative Findings table including a summary of each finding, confidence in that finding, and an explanation for the rating. Assessments for each finding will be made through discussion between PMP and JG.

The proposed systematic review will contribute to our knowledge of loneliness by clarifying how it is subjectively experienced across the lifespan. Synthesising the qualitative literature focusing on experiences of loneliness in the general population will offer a fine-grained, subjectively derived understanding of the components of this phenomenon which closely reflects the original descriptions provided by those who have experienced it. By including non-clinical populations of all ages, this research will provide an essential view of loneliness experiences across different life stages. This can be used to inform future research into correlates, consequences, and interventions for loneliness. The use of thematic synthesis will enable us to remain close to the data, offering an account which might also be useful for policy and practice in this area.

There are a number of limitations to the planned research. Primarily, this review will be unable to capture aspects of loneliness experiences which have not been described in the qualitative literature, for example, due to the sensitivity of the topic, given that loneliness can be stigmatising, or aspects that are specific to a given unstudied population. Moreover, by focusing on lifespan non-clinical research, we aim to offer a general synthesis which can in future be informed by insights from clinical groups, rather than subsuming and potentially obscuring the aspects of loneliness which might be unique to them. Whilst primary empirical studies are not themselves extensive sources, with books in particular often offering rich descriptions of loneliness (see, e.g. [ 11 , 46 ]), this research will focus on primary empirical studies of subjective descriptions to offer a manageable level of scope and rigour. As with any systematic review, some studies may also be missing information which would inform the synthesis. Quality appraisal and sensitivity analysis will aim to capture and potentially control for this issue, but it will ultimately be difficult to ascertain how missing information might affect the synthesis.

By providing a thorough overview of how loneliness is experienced, we expect that the findings from the planned review will be informative and useful for researchers, policymakers, and clinicians who work with and for people experiencing loneliness, as well as for these individuals themselves, to better understand this important, prevalent, and often misunderstood phenomenon. Mansfield et al. [ 18 ] have offered an illuminating systematic review covering the conceptual frameworks and models of loneliness included in the existing evidence base (i.e. social, emotional, and existential loneliness). This review will build upon this work by including research with children and adolescents and taking a bottom-up approach similar to grounded theory where the synthesis will remain close to the participants’ subjective descriptions of loneliness experiences within the included studies, rather than reflecting pre-existing themes in the evidence base. As such, this systematic review will offer specific insights into lifespan experiences of loneliness. This synthesis of lived experiences will shed light on the nuances of loneliness which existing definitions and typologies might overlook. It will offer an experience-focused overview of loneliness for people studying and developing measures of this phenomenon. In focusing on qualitative work, the planned review may also identify processes relevant to loneliness which are not expressed by statistical models. In this way, it may also provide a starting point for more nuanced qualitative work with specific populations and circumstances to ascertain components which may be characteristic of certain experiences.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research

Education Resource Information Center

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation – Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences

Joanna Briggs Institute

Jenny Groarke

Keming Yang

Phoebe McKenna-Plumley

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Protocol

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Review question – Epistemology – Time/Timescale – Resources – Expertise – Audience and purpose – Type of data

Rhiannon Turner

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

Department for Digital C, Media and Sport. A connected society: a strategy for tackling loneliness – laying the foundations for change. London; 2018.

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med\. 2010;40(2):218–27.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Zyphur MJ, Gleeson JF. Loneliness over time: the crucial role of social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(5):620–30.

Qualter P, Brown SL, Rotenberg KJ, Vanhalst J, Harris RA, Goossens L, et al. Trajectories of loneliness during childhood and adolescence: predictors and health outcomes. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1283–93.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.

Hammond C. The surprising truth about loneliness: BBC Future; 2018. Available from: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20180928-the-surprising-truth-about-loneliness .

Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J Psychol. 2012;146(1-2):85–104.

De Jong GJ, van Tilburg TG, Dykstra PA. Loneliness and social isolation. In: Perlman AVD, editor. The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. 485–500.

Google Scholar

Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE, Pitkälä KH. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(3):223–33.

Yang K. Loneliness: a social problem. New York: Department for Culture Media and Sport; 2019..

Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346–63.

Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Odgers CL, Ambler A, Moffitt TE, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(3):339–48.

Rokach A. The experience of loneliness: a tri-level model. J Psychol. 1988;122(6):531.

Article Google Scholar

Ojembe BU, Ebe KM. Describing reasons for loneliness among older people in Nigeria. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2018;61(6):640–58.

Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Duck S, Gilmour R, editors. Personal relationships in disorder. London: Academic; 1981. p. 31–56.

Weiss RS. Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. J Soc Behav Pers. 1987;2(2):271–6.

Mansfield L, Daykin N, Meads C, Tomlinson A, Gray K, Lane J, Victor C. A conceptual review of loneliness across the adult life course (16+ years): synthesis of qualitative studies: What Works Wellbeing, London; 2019.

Achterbergh L, Pitman A, Birken M, Pearce E, Sno H, Johnson S. The experience of loneliness among young people with depression: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):415.

Kitzmüller G, Clancy A, Vaismoradi M, Wegener C, Bondas T. “Trapped in an empty waiting room”—the existential human core of loneliness in old age: a meta-synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2017;28(2):213–30.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9 w64.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138237.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Stansfield C. Qualitative research 2014. Available from: https://sites.google.com/view/pearl-harvesting-search/ph-synonym-rings/structure-or-study-design/qualitative-research .

Kent-Marvick J, Simonsen S, Pentecost R, McFarland MM. Loneliness in pregnant and postpartum people and parents of children aged 5 years or younger: a scoping review protocol. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):213–9.

Michalska da Rocha B. Is there a relationship between loneliness and psychotic experiences? An empirical investigation and a meta-analysis [D.Clin. Psychol.]. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh; 2016.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Finding the findings in qualitative studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):213–9.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–87.

Soilemezi D, Linceviciute S. Synthesizing qualitative research: reflections and lessons learnt by two new reviewers. Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1):1609406918768014.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies (vol. 11). California: Sage; 1988.

Book Google Scholar

Lachal J, Revah-Levy A, Orri M, Moro MR. Metasynthesis: an original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:269.

Popay J, Roberts HM, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme; 2006.

Newton G, Griffith A, Soundy A. The experience of fatigue in neurological patients with multiple sclerosis: a thematic synthesis. Physiotherapy. 2020;107:306–16.

Tong A, Jones J, Craig JC, Singh-Grewal D. Children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(9):1392–404.

Heath G, Farre A, Shaw K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):76–92.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt GJ, et al. Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:41–52.

Institute JB. JBI reviewer’s manual – 2.4: the JBI approach to qualitative synthesis. 2019 Available from: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/2.4+The+JBI+Approach+to+qualitative+synthesis .

Carroll C, Booth A, Lloyd-Jones M. Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? An evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1425–34.

Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(2):149–54.

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):2.

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001895.

Bound AF. A biography of loneliness: the history of an emotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Ms. Norma Menabney and Ms. Carol Dunlop, subject librarians at the McClay Library, Queen’s University Belfast, for their advice and assistance with designing a search strategy for this review. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Ciara Keenan, a research fellow at Queen’s University Belfast and associate director of Cochrane Ireland, for her completion of the PRESS checklist and guidance regarding the search strategy and systematic review methodology.

PMP wishes to acknowledge the funding received from the Northern Ireland and North East Doctoral Training Partnership, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council with support from the Department for the Economy Northern Ireland. The funder did not play a role in the development of this protocol.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology, Queen’s University Belfast, David Keir Building, 18-30 Malone Road, Belfast, BT9 5BN, UK

Phoebe E. McKenna-Plumley, Jenny M. Groarke & Rhiannon N. Turner

Department of Sociology, Durham University, 29-32 Old Elvet, Durham, DH1 3HN, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PMP is the study guarantor. PMP and JG were responsible for the conception and design of the study. PMP, JG, RT, and KY contributed to the drafting and revising of the protocol. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Phoebe E. McKenna-Plumley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search executed in MEDLINE ALL (OVID) 16/11/2020.

Additional file 3.

PRESS Guideline — Search Submission & Peer Review Assessment.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McKenna-Plumley, P.E., Groarke, J.M., Turner, R.N. et al. Experiences of loneliness: a study protocol for a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Syst Rev 9 , 284 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01544-x

Download citation

Received : 28 May 2020

Accepted : 25 November 2020

Published : 06 December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01544-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Experiences of loneliness

- Systematic review

- Thematic synthesis

- Qualitative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Loneliness: contemporary insights into causes, correlates, and consequences

- Published: 11 June 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 789–791, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- M. H. Lim 1 , 2 ,

- J. Holt-Lunstad 1 , 3 &

- J. C. Badcock 4

9823 Accesses

35 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Loneliness is not a new phenomenon but in recent years, there has been a growing interest in understanding how feelings of ‘perceived social isolation’ can influence our health and wellbeing. Objective indicators of social isolation—such as living alone and number of social connections—have well-demonstrated links with poorer health outcomes [ 1 ]. However, the latest evidence indicates that feeling lonely is also associated with a multitude of poorer health outcomes, ranging from an increased risk of depression and dementia [ 2 ], increased risk of heart disease and stroke [ 3 ] and higher levels of inflammatory responses [ 4 ] to name a few. Indeed, those who are socially isolated (odds ratio = 1.29; 95% CI 1.06, 1.56), living alone (odds ratio = 1.32; 95% CI 1.14, 1.53), or those who are lonely (odds ratio = 1.26, 95% CI 1.04, 1.53) are at increased risk of earlier mortality [ 5 ].

Current “hotspots” in loneliness research include studies examining how perceived social isolation influences mental health symptoms [ 6 ] and disorders [ 7 , 8 , 9 ], older [ 10 ] and younger adults [ 11 ], workplace productivity [ 12 , 13 ], and social media use [ 14 ]. The contributions to this special issue illustrate some of the progress, possibilities, and problems in contemporary research on loneliness, including two systematic reviews [ 15 , 16 ], one conceptual review [ 17 ], two pilot studies evaluating a novel approach to reduce loneliness in young people with psychosis [ 18 , 19 ], and two studies exploring personalized approaches to reduce loneliness [ 20 , 21 ].

First, Ma et al. (2019) provide a review of the effectiveness of interventions targeting subjective and objective social isolation in people with different mental health problems [ 15 ]. The authors examined: (1) interventions that alter maladaptive cognitions about others (e.g., cognitive-behavioural therapy); (2) social skills training and psychoeducation programmes (e.g., family psychoeducation therapy); (3) supported socialisation (e.g., peer support groups); and (4) community approaches (e.g., social prescribing). When considering only those studies specifically targeting interventions for loneliness, Ma et al. [ 15 ] found that the most promising results emerged for cognition modification interventions.

The study by Mihalopoulos et al. [ 16 ] highlights the importance of understanding the economic burden of loneliness and/or social isolation and is one of the first to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting loneliness and/or social isolation. The authors reported that all but one of the published cost-of-illness studies indicated greater healthcare costs for individuals experiencing loneliness and/or social isolation. However, Mihalopoulos et al. [ 16 ] noted that these costs “are likely to be underestimated” due to the limited evidence available, particularly for younger populations. Of the interventions included in this systematic review, the authors highlight “promising” cost-effective interventions that involved increasing social and peer-contact.

In the conceptual review by Lim, Eres, and Vasan [ 17 ], the authors outline emerging and established correlates and risk factors associated with loneliness. Importantly, the review identified two newer variables of interest in loneliness research, namely workplaces and the use of digital communication. Lim and colleagues also highlight the complexity of loneliness and introduce a new conceptual model that describes how multiple risk factors/correlates can affect loneliness severity. The authors stress that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for loneliness; rather, how loneliness is resolved is dependent on an individual’s circumstances and available resources.

The next two studies illustrate how a theory-driven approach (i.e., strengths-based positive psychology) was used to develop an intervention targeting loneliness. In a brief report, Lim et al. [ 18 ] evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a positive psychology intervention group program called Positive Connect for young people experiencing psychosis. This 6-week positive psychology group intervention was designed to help young people identify their strengths and practice interpersonal skills that could be used to build close relationships with others. Preliminary evidence presented suggests that the program is both feasible and acceptable for this patient population. Encouragingly, exploratory analyses also indicate a positive benefit for reducing loneliness over time.

In the second related study, the authors describe the development of the same positive psychology program being translated and delivered via a digital smartphone app called + Connect [ 19 ]. The authors used focus groups to steer the design, functionality, and language of the 6-week program, to facilitate consumer engagement. Using an innovative blend of content, concepts were conveyed via text and videos (featuring young people with lived experience, academics, and actors). The feasibility, acceptability, and usability of + Connect is reported for a pilot sample ( N = 12) of young people with psychosis, along with tentative evidence of a benefit in reducing loneliness.

The next study by Tymoszuk et al. [ 20 ] looked at the impact of arts engagement on loneliness, specifically, whether the frequency of receptive arts engagement was associated with lower odds of loneliness in older adults. The authors used existing data drawn from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), analyzing participants (over 50 years old) with complete data on engagement with arts, covariate variables, and loneliness from the second wave ( n = 6222) for cross-sectional analyses, and loneliness data from the seventh wave ( n = 3127) for longitudinal analyses. In cross-sectional findings, frequent engagement with arts activities was associated with lowers odds of loneliness. However, longitudinal findings were less supportive, including no evidence that cinema engagement reduced loneliness.

Finally, consistent with the need to develop individualized solutions, Wang et al. [ 21 ] examined variables associated with loneliness for individuals (18–75 years old) leaving a Crisis Resolution Team (CRT). A total of 399 participants, with most reporting depression/anxiety disorders (35.0%), followed by schizophrenia/psychosis (27.0%), bipolar affective/manic (16.3%), and other disorders (8.4%) were included in the analyses. Results showed that loneliness was more severe for individuals who have more mental health contact over the years (2–10 years), compared to those who have less than 3 months, and those who have less than 1 year of mental health service contact. Higher loneliness was also associated with more severe affective, positive or negative symptoms. Those who had depression, anxiety, personality disorders or other disorders compared with those who had psychotic disorders were also lonelier. In those with a mental disorder, lower loneliness was also associated with greater social network size and increased neighbourhood social capital [ 21 ].

Many of the studies in this special issue, draw attention to the importance of the need for rigorous loneliness research so that we can extend our knowledge on how loneliness impacts on health. Accordingly, it is crucial that we measure loneliness as a key variable of interest alongside specific health-related outcomes in future research. In doing so, we are also more likely to measure loneliness in a comprehensive way using psychometrically validated assessment tools, avoiding dichotomous measurement of loneliness to draw accurate comparisons across different samples. Given the significant public health implications, the current studies also call attention to the need for a routine and consistent approach to assessing and documenting loneliness as psychosocial “vital signs” of care [ 7 ].

Many of the reviewed studies also highlight the need to conduct longitudinal research to clarify the relationships between loneliness and poorer health outcomes. Pertinent questions such as ‘are people with pre-existing health problems more predisposed to feeling lonely’, or ‘are people who are lonely more predisposed to developing problematic health conditions?’ have significant, real-world implications for the development of effective treatments.

In addition, it is also clear that greater attention is needed in the development and evaluation of solutions/interventions for loneliness. Designing consumer relevant programs can improve uptake and adherence to programs and Lim et al.’s study shows an example of how consumers are increasingly engaged within research to help tailor evidence-based material to be more engaging to relevant groups [ 19 ]. However, there is currently mixed evidence of what is helpful and unhelpful for loneliness in terms of solutions. Hence, solely relying on consumers’ ideas concerning what they can do to address their own loneliness may be helpful for engagement but may not be necessarily effective. What is more crucial is the rigorous evaluation of theory-driven evidence-based interventions that are intended to reduce loneliness, and researchers need to move swiftly from pilot evaluations to high quality, adequately powered randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Furthermore, economic evaluations of interventions should be more frequently included in RCTs, to further augment the evidence-base. This involves including both resource use, cost and utility information, and ensuring that the economic evaluation examines both the costs and benefits in healthcare.

Clearly, there are many unanswered questions. For example, if loneliness is a common experience, when does loneliness make a significant negative impact on health outcomes? When does loneliness as a transient experience become a chronic issue? Much work is required to understand the negative impact of loneliness on ourselves, our community and the society we live in and we look forward to learning more about loneliness within a dynamic social world.

Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D et al (2013) Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health 11:2056–2062. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261

Article Google Scholar

Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Dennis MS et al (2013) Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

Hawkley LC, Burleson MH, Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT (2003) Loneliness in everyday life: cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol 1:105. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.105

Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L (2004) Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 5:593–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00086-6

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7:e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Zyphur MJ, Gleeson JF (2016) Loneliness over time: the crucial role of social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol 5:620–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000162

Badcock JC, Mackinnon A, Waterreus A et al (2018) Loneliness in psychotic illness and its association with cardiometabolic disorders. Schizophr Res 204:90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.021

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Badcock JC, Shah S, Mackinnon A et al (2015) Loneliness in psychotic disorders and its association with cognitive function and symptom profile. Schizophr Res 1–3:268–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.10.027

Lim MH, Gleeson JFM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Penn DL (2018) Loneliness in psychosis: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 3:221–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1482-5

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA (2010) Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Psychol Aging 2:453–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216

Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Eres R et al (2019) A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in youth mental health. Front Psychiatry 10:604. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00604

Ozcelik H (2011) Barsade S (2011) Work loneliness and employee performance. Acad Manag Proc 1:1–6. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2011.65869714

Ozcelik H, Barsade SG (2018) No employee island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manag J 6:2343–2366. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.1066

Nowland R, Necka EA, Cacioppo JT (2017) Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect Psychol Sci 1:70–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617713052

Ma R, Mann F, Wang J et al (2019) The effectiveness of interventions for reducing subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01800-z

Mihalopoulos C, Le LK, Chatterton ML et al (2019) The economic costs of loneliness: a review of cost-of-illness and economic evaluation studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01733-7

Lim MH, Eres R, Vasan S (2020) Loneliness in the 21st century: an update on correlates, risk factors and potential solutions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7

Lim MH, Penn DL, Thomas N, Gleeson JFM (2019) Is loneliness a feasible treatment target in psychosis? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01731-9

Lim MH, Gleeson JFM, Rodebaugh TL, Eres R, Long KM, Casey K, Abbott J-AM, Thomas N, Penn DL (2019) A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in young people with psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01681-2

Tymoszuk U, Perkins R, Fancourt D, Williamon A (2019) Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between receptive arts engagement and loneliness among older adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01764-0

Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Marston L et al (2019) Epidemiology of loneliness in a cohort of UK mental health community crisis service users. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01734-6

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Iverson Health Innovation Research Institute, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

M. H. Lim & J. Holt-Lunstad

Centre for Mental Health, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, 84602, USA

J. Holt-Lunstad

University of Western Australia, Perth, WA, Australia

J. C. Badcock

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to M. H. Lim .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lim, M.H., Holt-Lunstad, J. & Badcock, J.C. Loneliness: contemporary insights into causes, correlates, and consequences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55 , 789–791 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01891-z

Download citation

Published : 11 June 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01891-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Exploring the experiences of loneliness in adults with mental health problems: A participatory qualitative interview study

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation The Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network Co-Production Group, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit COVID-19 Co-Production Group, Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Centre for Performance Science, Royal College of Music, London, United Kingdom, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, Department of Health Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- [ ... ],

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, United Kingdom, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

- [ view all ]

- [ view less ]

- Mary Birken,

- Beverley Chipp,

- Prisha Shah,

- Rachel Rowan Olive,

- Patrick Nyikavaranda,

- Jackie Hardy,

- Anjie Chhapia,

- Nick Barber,

- Stephen Lee,

- Published: March 7, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280946

- Reader Comments

Loneliness is associated with many mental health conditions, as both a potential causal and an exacerbating factor. Richer evidence about how people with mental health problems experience loneliness, and about what makes it more or less severe, is needed to underpin research on strategies to help address loneliness.

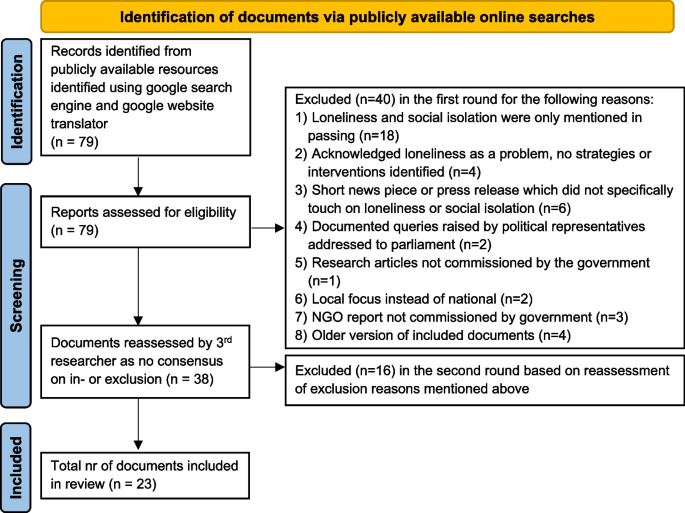

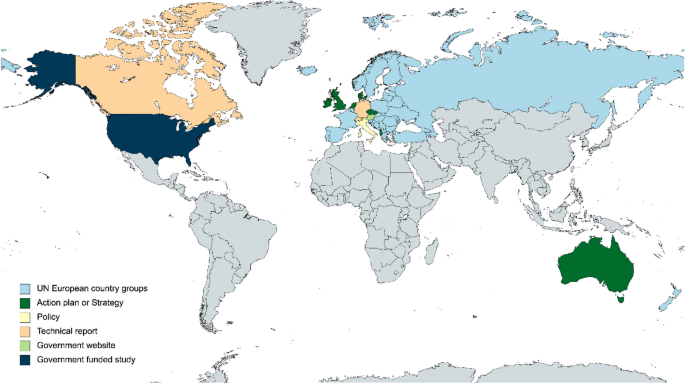

Our aim was to explore experiences of loneliness, as well as what helps address it, among a diverse sample of adults living with mental health problems in the UK. We recruited purposively via online networks and community organisations, with most interviews conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 59 consenting participants face-to-face, by video call or telephone. Researchers with relevant lived experience were involved at all stages, including design, data collection, analysis and writing up of results.

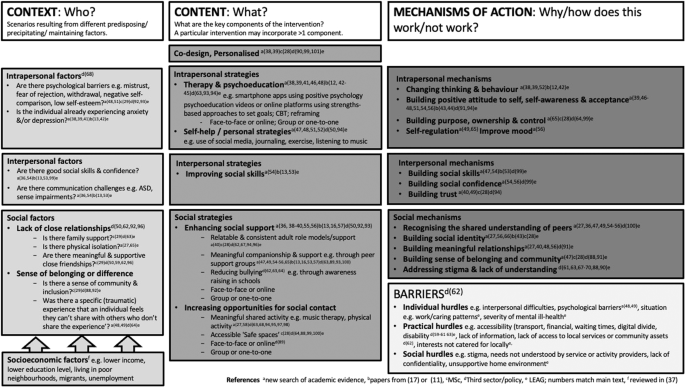

Analysis led to identification of four overarching themes: 1. What the word “lonely” meant to participants, 2. Connections between loneliness and mental health, 3. Contributory factors to continuing loneliness, 4. Ways of reducing loneliness. Central aspects of loneliness were lack of meaningful connections with others and lack of a sense of belonging to valued groups and communities. Some drivers of loneliness, such as losses and transitions, were universal, but specific links were also made between living with mental health problems and being lonely. These included direct effects of mental health symptoms, the need to withdraw to cope with mental health problems, and impacts of stigma and poverty.

Conclusions

The multiplicity of contributors to loneliness that we identified, and of potential strategies for reducing it, suggest that a variety of approaches are relevant to reducing loneliness among people with mental health problems, including peer support and supported self-help, psychological and social interventions, and strategies to facilitate change at community and societal levels. The views and experiences of adults living with mental health problems are a rich source for understanding why loneliness is frequent in this context and what may address it. Co-produced approaches to developing and testing approaches to loneliness interventions can draw on this experiential knowledge.

Citation: Birken M, Chipp B, Shah P, Olive RR, Nyikavaranda P, Hardy J, et al. (2023) Exploring the experiences of loneliness in adults with mental health problems: A participatory qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0280946. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280946

Editor: Giuseppe Carrà, Universita degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, ITALY

Received: March 8, 2022; Accepted: January 11, 2023; Published: March 7, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Birken et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Full transcriptions of the interviews analysed in this study cannot be shared publicly to protect the privacy and anonymity of participants. If you wish to obtain access to this data, please contact the UCL ethics committee on [email protected] and/or the corresponding author.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the UK Research and Innovation, through the Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network (grant no. ES/S004440/1, co-authors MB, BC, PS, JH, AC, NB, SL, EP, BLE, RP, DM, RS, AP, SJ). The study was further supported through funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme, conducted by the NIHR Policy Research Unit (PRU) (grant no. PR-PRU-0916-22003, co-authors RRO, PN, BLE, SJ) in Mental Health. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UKRI or NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or its arm’s length bodies, or other government departments. Neither the funding bodies nor the sponsors played any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Inter-relationships between loneliness and mental health problems are the focus of a growing body of literature [ 1 ]. Loneliness is defined as a subjective experience where individuals feel there is a discrepancy between social relationships that they desire to have and those they actually have [ 2 ]. Loneliness is more prevalent among people with mental health problems than the general population [ 1 , 3 , 4 ].

Important associations are found between loneliness and a range of health indicators. It is a risk factor for multiple poor physical health outcomes, including early mortality, impaired cognition, hypertension, stroke, and cardiovascular disease [ 5 – 8 ]. Health service use is greater among lonely people, especially older people [ 9 , 10 ]. Regarding mental health, loneliness appears to put people at risk of onset of depression [ 11 , 12 ], whilst loneliness (and a closely related construct, lack of subjective social support) is associated longitudinally with recovering less well from mental health problems [ 13 , 14 ].

Whilst the evidence linking loneliness to mental ill health, as well as its inherently distressing nature, make loneliness a potentially promising focus for developing strategies to improve quality of life and outcomes among people living with mental health problems [ 15 ], few evidence-based and implementation-ready interventions are available [ 16 ]. Strategies to reduce loneliness are more likely to be successful if rooted in an understanding of what people with mental health problems mean when they say they are lonely, how this relates to experiences of mental distress, and what they find improves or exacerbates loneliness. Much of the empirical research on loneliness and mental health has deployed measures that treat loneliness as a straightforward uni-dimensional phenomenon. This is despite philosophical, historical and experiential writing suggesting that the term captures a complex cluster of emotions and experiences [ 17 , 18 ]. Currently used measures are also not tailored to investigating loneliness in the context of mental ill-health, nor have they been developed in collaboration with people with relevant lived experience.

Qualitative research on lived experiences of loneliness among people with mental health problems has important potential to yield a deeper account of the nature of such experiences and what improves or exacerbates loneliness. Such an understanding should underpin further research, including development of interventions, measures and hypotheses for quantitative investigations. The few published investigations are small-scale, and suggest a complex, intertwined relationship. A phenomenological study of people diagnosed with “borderline personality disorder” [ 19 ] found that participants perceived loneliness as rooted in traumatic early experiences and strongly associated with negative feelings about self and others. Participants also described feeling disconnected from those around them and on the outside of social activities at which they were present. Lindgren and colleagues [ 20 ] interviewed five individuals with mental health problems, who described multifaceted and shifting experiences of loneliness that varied with life situation but were also persistent. A meta-synthesis of studies on the experience of loneliness among young people with depression identified a range of factors, including depressive symptoms, non-disclosure of depression, and fear of stigma, which perpetuated cycles of loneliness and depression [ 21 ]. However, the qualitative literature on loneliness experiences among people living with mental health problems overall remains very limited in scope and size.

Our aim in the current study is therefore to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of loneliness among a broad range of people living with mental health problems. This was identified as a high priority evidence gap by the UKRI (United Kingdom Research and Innovation) Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Research Network, a cross-disciplinary research network established to advance research on the relationship between loneliness and mental health [ 22 ].

We present data from a qualitative interview study [ 23 ] which employed a co-production approach [ 24 ], involving collaboration between people with relevant lived experience, clinicians and university-employed researchers (some of the team had multiple relevant perspectives). Semi-structured individual interviews were used to explore the experiences of loneliness in adults with mental health problems.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University College London Research Ethics Committee on 19/12/2019 (Ref: 15249/001), with a subsequent amendment approved to extend the study to include experience of the COVID-19 pandemic among people with mental health problems, meeting a pressing need for this. In this paper we report only on findings relevant to the original question regarding experiences of loneliness and their relationship with mental health. Findings relevant to the pandemic are reported in three other papers [ 23 , 25 , 26 ].

Research team

A team of Lived Experience Researchers, (LERs), drawing on their own experiential knowledge about living with mental health problems, and other researchers from the UKRI Loneliness and Social Isolation and Mental Health network and the National Institute for Health and Care Research Mental Health Policy Research Unit (MHPRU) planned and conducted the study. The team included clinical academics and non-clinical researchers from a range of backgrounds (including qualitative and mixed methods research, health policy, health economics, and the arts). The research team met weekly by Zoom video call [ 27 ] to plan the study and discuss progress. Most interviews were conducted by thirteen LERs involved in the study, except for eight telephone interviews conducted by MB, an experienced qualitative researcher and occupational therapist. Three LERs were employed in university research roles; others had honorary research contracts with University College London. Eleven of the LER interviewers were female and five were from minority ethnic backgrounds. The LERs received training on conducting face-to-face and online interviews and obtaining written and verbal informed consent. A weekly lived experience reflective space provided LERs with emotional support and space to discuss the research process and emotional impact, peer-facilitated by four experienced LERs.

Sampling and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to ensure diversity regarding participants’ diagnoses, use of mental health services, and demographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality, and whether they lived in rural or urban areas. We reviewed our sample during recruitment and implemented targeted strategies to ensure diversity. These included approaching community organisations working with Black and Minority Ethnic communities and using targeted recruitment materials.

Participants were eligible to take part if they were aged 18 years or over, had a self-reported mental health problem and lived in the UK. We recruited through three London-based community organisations (a mental health charity, a homeless charity and a community arts organisation), as well as through social media, especially Twitter, supported by the Mental Elf. Several charities and community organisations supporting people with mental health problems also agreed to disseminate an invitation to participate to their networks. Potential participants contacted the research team by email. Researchers then checked eligibility, provided a participant information sheet, answered questions about the study, and booked interviews.

Data collection

The topic guide (see S1 Appendix ) was developed collaboratively by members of the Loneliness Network’s Co-Production Group to explore the nature of loneliness experiences, their relationship to mental health, and alleviating and exacerbating factors. Prompts were included for questions asked to ensure topics were fully explored. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, further questions were added regarding experiences of living with mental health problems during the pandemic (see S2 Appendix for revised topic guide). Semi-structured interviews took place between March and July 2020. Ten participants were interviewed before the introduction of COVID-19 infection control measures, (two face-to-face with LERs and 8 by phone with MB and 49 participated in online interviews with LERs following the pandemic’s onset. Informed consent (verbal or written) was obtained prior to all interviews. All interviews were audio-recorded, with verbatim transcripts produced by an external transcription company. All transcripts were then checked by the researchers and any identifying information was anonymised.