Bipolar disorders

Affiliations.

- 1 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Pharmacology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, ON, Canada. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Institute for Mental and Physical Health and Clinical Translation Strategic Research Centre, School of Medicine, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Mental Health Drug and Alcohol Services, Barwon Health, Geelong, VIC, Australia; Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Centre for Youth Mental Health, Florey Institute for Neuroscience and Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Department of Psychiatry, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Adult Division, Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, Queen's University School of Medicine, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada; Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Centre for Youth Bipolar Disorder, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 5 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia; Mood Disorders Program, Hospital Universitario San Vicente Fundación, Medellín, Colombia.

- 6 Copenhagen Affective Disorders Research Centre, Psychiatric Center Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 7 Discipline of Psychiatry, Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; Department of Academic Psychiatry, Northern Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia.

- 8 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 9 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Dauten Family Center for Bipolar Treatment Innovation, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

- 10 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 11 Hospital Clinic, Institute of Neuroscience, University of Barcelona, IDIBAPS, CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Spain.

- 12 Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Psychiatric Research Unit, Psychiatric Centre North Zealand, Hillerød, Denmark.

- 13 Department of Psychological Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London and South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust, Bethlem Royal Hospital, London, UK.

- 14 Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada; Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- PMID: 33278937

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31544-0

Bipolar disorders are a complex group of severe and chronic disorders that includes bipolar I disorder, defined by the presence of a syndromal, manic episode, and bipolar II disorder, defined by the presence of a syndromal, hypomanic episode and a major depressive episode. Bipolar disorders substantially reduce psychosocial functioning and are associated with a loss of approximately 10-20 potential years of life. The mortality gap between populations with bipolar disorders and the general population is principally a result of excess deaths from cardiovascular disease and suicide. Bipolar disorder has a high heritability (approximately 70%). Bipolar disorders share genetic risk alleles with other mental and medical disorders. Bipolar I has a closer genetic association with schizophrenia relative to bipolar II, which has a closer genetic association with major depressive disorder. Although the pathogenesis of bipolar disorders is unknown, implicated processes include disturbances in neuronal-glial plasticity, monoaminergic signalling, inflammatory homoeostasis, cellular metabolic pathways, and mitochondrial function. The high prevalence of childhood maltreatment in people with bipolar disorders and the association between childhood maltreatment and a more complex presentation of bipolar disorder (eg, one including suicidality) highlight the role of adverse environmental exposures on the presentation of bipolar disorders. Although mania defines bipolar I disorder, depressive episodes and symptoms dominate the longitudinal course of, and disproportionately account for morbidity and mortality in, bipolar disorders. Lithium is the gold standard mood-stabilising agent for the treatment of people with bipolar disorders, and has antimanic, antidepressant, and anti-suicide effects. Although antipsychotics are effective in treating mania, few antipsychotics have proven to be effective in bipolar depression. Divalproex and carbamazepine are effective in the treatment of acute mania and lamotrigine is effective at treating and preventing bipolar depression. Antidepressants are widely prescribed for bipolar disorders despite a paucity of compelling evidence for their short-term or long-term efficacy. Moreover, antidepressant prescription in bipolar disorder is associated, in many cases, with mood destabilisation, especially during maintenance treatment. Unfortunately, effective pharmacological treatments for bipolar disorders are not universally available, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. Targeting medical and psychiatric comorbidity, integrating adjunctive psychosocial treatments, and involving caregivers have been shown to improve health outcomes for people with bipolar disorders. The aim of this Seminar, which is intended mainly for primary care physicians, is to provide an overview of diagnostic, pathogenetic, and treatment considerations in bipolar disorders. Towards the foregoing aim, we review and synthesise evidence on the epidemiology, mechanisms, screening, and treatment of bipolar disorders.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Anticonvulsants / therapeutic use

- Antidepressive Agents / therapeutic use

- Antimanic Agents / therapeutic use

- Antipsychotic Agents / therapeutic use

- Bipolar Disorder / classification*

- Bipolar Disorder / drug therapy*

- Bipolar Disorder / genetics

- Bipolar Disorder / psychology

- Carbamazepine / therapeutic use

- Cardiovascular Diseases / complications

- Cardiovascular Diseases / mortality

- Child Abuse / psychology

- Comorbidity

- Depressive Disorder, Major / drug therapy*

- Depressive Disorder, Major / genetics

- Depressive Disorder, Major / psychology

- Environmental Exposure / adverse effects

- Lamotrigine / therapeutic use

- Lithium / therapeutic use

- Mania / drug therapy

- Mania / psychology

- Suicide / psychology

- Suicide Prevention*

- Valproic Acid / therapeutic use

- Young Adult

- Anticonvulsants

- Antidepressive Agents

- Antimanic Agents

- Antipsychotic Agents

- Carbamazepine

- Valproic Acid

- Lamotrigine

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Diagnosis and...

Diagnosis and management of bipolar disorders

- Related content

- Peer review

- Fernando S Goes , associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences 1 2

- 1 Precision Medicine Center of Excellence in Mood Disorders, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- 2 Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

- Correspondence to: F S Goes fgoes1{at}jhmi.edu

Bipolar disorders (BDs) are recurrent and sometimes chronic disorders of mood that affect around 2% of the world’s population and encompass a spectrum between severe elevated and excitable mood states (mania) to the dysphoria, low energy, and despondency of depressive episodes. The illness commonly starts in young adults and is a leading cause of disability and premature mortality. The clinical manifestations of bipolar disorder can be markedly varied between and within individuals across their lifespan. Early diagnosis is challenging and misdiagnoses are frequent, potentially resulting in missed early intervention and increasing the risk of iatrogenic harm. Over 15 approved treatments exist for the various phases of bipolar disorder, but outcomes are often suboptimal owing to insufficient efficacy, side effects, or lack of availability. Lithium, the first approved treatment for bipolar disorder, continues to be the most effective drug overall, although full remission is only seen in a subset of patients. Newer atypical antipsychotics are increasingly being found to be effective in the treatment of bipolar depression; however, their long term tolerability and safety are uncertain. For many with bipolar disorder, combination therapy and adjunctive psychotherapy might be necessary to treat symptoms across different phases of illness. Several classes of medications exist for treating bipolar disorder but predicting which medication is likely to be most effective or tolerable is not yet possible. As pathophysiological insights into the causes of bipolar disorders are revealed, a new era of targeted treatments aimed at causal mechanisms, be they pharmacological or psychosocial, will hopefully be developed. For the time being, however, clinical judgment, shared decision making, and empirical follow-up remain essential elements of clinical care. This review provides an overview of the clinical features, diagnostic subtypes, and major treatment modalities available to treat people with bipolar disorder, highlighting recent advances and ongoing therapeutic challenges.

Introduction

Abnormal states of mood, ranging from excesses of despondency, psychic slowness, diminished motivation, and impaired cognitive functioning on the one hand, and exhilaration, heightened energy, and increased cognitive and motoric activity on the other, have been described since antiquity. 1 However, the syndrome in which both these pathological states occur in a single individual was first described in the medical literature in 1854, 2 although its fullest description was made by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin at the turn of the 19th century. 3 Kraepelin emphasized the periodicity of the illness and proposed an underlying trivariate model of mood, thought (cognition), and volition (activity) to account for the classic forms of mania and depression and the various admixed presentations subsequently know as mixed states. 3 These initial descriptions of manic depressive illness encompassed most recurrent mood syndromes with relapsing remitting course, minimal interepisode morbidity, and a wide spectrum of “colorings of mood” that pass “without a sharp boundary” from the “rudiment of more severe disorders…into the domain of personal predisposition.” 3 Although Kraepelin’s clinical description of bipolar disorder (BD) remains the cornerstone of today’s clinical description, more modern conceptions of bipolar disorder have differentiated manic depressive illness from recurrent depression, 4 partly based on differences in family history and the relative specificity of lithium carbonate and mood stabilizing anticonvulsants as anti-manic and prophylactic agents in bipolar disorder. While the boundaries of bipolar disorder remain a matter of controversy, 5 this review will focus on modern clinical conceptions of bipolar disorder, highlighting what is known about its causes, prognosis, and treatments, while also exploring novel areas of inquiry.

Sources and selection criteria

PubMed and Embase were searched for articles published from January 2000 to February 2023 using the search terms “bipolar disorder”, “bipolar type I”, “bipolar type II”, and “bipolar spectrum”, each with an additional search term related to each major section of the review article (“definition”, “diagnosis”, “nosology”, “prevalence”, “epidemiology”, “comorbid”, “precursor”, “prodrome”, “treatment”, “screening”, “disparity/ies”, “outcome”, “course”, “genetics”, “imaging”, “treatment”, “pharmacotherapy”, “psychotherapy”, “neurostimulation”, “convulsive therapy”, “transmagnetic”, “direct current stimulation”, “suicide/suicidal”, and “precision”). Searches were prioritized for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, followed by randomized controlled trials. For topics where randomized trials were not relevant, searches also included narrative reviews and key observational studies. Case reports and small observations studies or randomized controlled trials of fewer than 50 patients were excluded.

Modern definitions of bipolar disorder

In the 1970s, the International Classification of Diseases and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders reflected the prototypes of mania initially described by Kraepelin, following the “neo-Kraepelinian” model in psychiatric nosology. To meet the primary requirement for a manic episode, an individual must experience elevated or excessively irritable mood for at least a week, accompanied by at least three other typical syndromic features of mania, such as increased activity, increased speed of thoughts, rapid speech, changes in esteem, decreased need for sleep, or excessive engagement in impulsive or pleasurable activities. Psychotic symptoms and admission to hospital can be part of the diagnostic picture but are not essential to the diagnosis. In 1994, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , fourth edition (DSM-IV) carved out bipolar disorder type II (BD-II) as a separate diagnosis comprising milder presentations of mania called hypomania. The diagnostic criteria for BD-II are similar to those for bipolar disorder type I (BD-I), except for a shorter minimal duration of symptoms (four days) and the lack of need for significant role impairment during hypomania, which might be associated with enhanced functioning in some individuals. While the duration criteria for hypomania remain controversial, BD-II has been widely accepted and shown to be as common as (if not more common than) BD-I. 6 The ICD-11 (international classification of diseases, 11th revision) included BD-II as a diagnostic category in 2019, allowing greater flexibility in its requirement of hypomania needing to last several days.

The other significant difference between the two major diagnostic systems has been their consideration of mixed symptoms. Mixed states, initially described by Kraepelin as many potential concurrent combinations of manic and depressive symptoms, were more strictly defined by DSM as a week or more with full syndromic criteria for both manic and depressive episodes. In DSM-5, this highly restrictive criterion was changed to encompass a broader conception of subsyndromal mixed symptoms (consisting of at least three contrapolar symptoms) in either manic, hypomanic, or depressive episodes. In ICD-11, mixed symptoms are still considered to be an episode, with the requirement of several prominent symptoms of the countervailing mood state, a less stringent requirement that more closely aligns with Kraepelin's broader conception of mixed states. 7

Epidemiology

Using DSM-IV criteria, the National Comorbidity Study replication 6 found similar lifetime prevalence rates for BD-I (1.0%) and BD-II (1.1%) among men and women. Subthreshold symptoms of hypomania (bipolar spectrum disorder) were more common, with prevalence rate estimates of 2.4%. 6 Incidence rates, which largely focus on BD-I, have been estimated at approximately 6.1 per 100 000 person years (95% confidence interval 4.7 to 8.1). 8 Estimates of the incidence and lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder show moderate variations according to the method of diagnosis (performed by lay interviewers in a research context v clinically trained interviews) and the racial, ethnic, and demographic context. 9 Higher income, westernized countries have slightly higher rates of bipolar disorder, 10 which might reflect a combination of westernized centricity in the specific idioms used to understand and elicit symptoms, as well as a greater knowledge, acceptance, and conceptualization of emotional symptoms as psychiatric disorders.

Causes of bipolar disorder

Like other common psychiatric disorders, bipolar disorder is likely caused by a complex interplay of multiple factors, both at the population level and within individuals, 11 which can be best conceptualized at various levels of analysis, including genetics, brain networks, psychological functioning, social support, and other biological and environmental factors. Because knowledge about the causes of bipolar disorder remains in its infancy, for pragmatic purposes, most research has followed a reductionistic model that will ultimately need to be synthesized for a more coherent view of the pathophysiology that underlies the condition.

Insights from genetics

From its earliest descriptions, bipolar disorder has been observed to run in families. Indeed, family history is the strongest individual risk factor for developing the disorder, with first degree relatives having an approximately eightfold higher risk of developing bipolar disorder compared with the baseline population rates of ~1%. 12 While family studies cannot separate the effects of genetics from behavioral or cultural transmission, twin and adoption studies have been used to confirm that the majority of the familial risk is genetic in origin, with heritability estimates of approximately 60-80%. 13 14 There have been fewer studies of BD-II, but its heritability has been found to be smaller (~46%) 15 and closer to that of more common disorders such as major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety. 15 16 Nevertheless, significant heritability does not necessarily imply the presence of genes of large effect, since the genetic risk for bipolar disorder appears likely to be spread across many common variants of small effect sizes. 16 17 Ongoing studies of rare variations have found preliminary evidence for variants of slightly higher effect sizes, with initial evidence of convergence with common variations in genes associated with the synapse and the postsynaptic density. 18 19

While the likelihood that the testing of single variants or genes will be useful for diagnostic purposes is low, analyses known as polygenic risk studies can sum across all the risk loci and have some ability to discriminate cases from controls, albeit at the group level rather than the individual level. 20 These polygenic risk scores can also be used to identify shared genetic risk factors across other medical and psychiatric disorders. Bipolar disorder has strong evidence for common variant based coheritability with schizophrenia (genetic correlation (r g ) 0.69) and major depressive disorder (r g 0.48). BD-I has stronger coheritability with schizophrenia compared with BD-II, which is more strongly genetically correlated with major depressive disorder (r g 0.66). 16 Lower coheritability was observed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (r g 0.21), anorexia nervosa (0.20), and autism spectrum disorder (r g 0.21). 16 These correlations provide evidence for shared genetic risk factors between bipolar disorder and other major psychiatric syndromes, a pattern also corroborated by recent nationwide registry based family studies. 12 14 Nevertheless, despite their potential usefulness, polygenic risk scores must currently be interpreted with caution given their lack of populational representation and lingering concerns of residual confounds such as gene-environment correlations. 21

Insights from neuroimaging

Similarly to the early genetic studies, small initial studies had limited replication, leading to the formation of large worldwide consortiums such as ENIGMA (enhancing neuroimaging genetics through meta-analysis) which led to substantially larger sample sizes and improved reproducibility. In its volumetric analyses of subcortical structures from MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of patients with bipolar disorder, the ENIGMA consortium found modest decreases in the volume of the thalamus (Cohen’s d −0.15), the hippocampus (−0.23), and the amygdala (−0.11), with an increased volume seen only in the lateral ventricles (+0.26). 22 Meta-analyses of cortical regions similarly found small reductions in cortical thickness broadly across the parietal, temporal, and frontal cortices (Cohen’s d −0.11 to −0.29) but no changes in cortical surface area. 23 In more recent meta-analyses of white matter tracts using diffuse tension imaging, widespread but modest decreases in white matter integrity were found throughout the brain in bipolar disorder, most notably in the corpus callosum and bilateral cinguli (Cohen’s d −0.39 to −0.46). 24 While these findings are likely to be highly replicable, they do not, as yet, have clinical application. This is because they reflect differences at a group level rather than an individual level, 25 and because many of these patterns are also seen across other psychiatric disorders 26 and could be either shared risk factors or the effects of confounding factors such as medical comorbidities, medications, co-occurring substance misuse, or the consequences (rather than causes) of living with mental illness. 27 Efforts to collate and meta-analyze large samples utilizing longitudinal designs 28 task based, resting state functional MRI measurents, 29 as well as other measures of molecular imaging (magnetic resonance spectroscopy and positron emission tomography) are ongoing but not as yet synthesized in large scale meta-analyses.

Environmental risk factors

Because of the difficulty in measuring and studying the relevant and often common environmental risk factors for a complex illness like bipolar disorder, there has been less research on how environmental risk factors could cause or modify bipolar disorder. Evidence for intrauterine risk factors is mixed and less compelling than such evidence in disorders like schizophrenia. 30 Preliminary evidence suggests that prominent seasonal changes in solar radiation, potentially through its effects on circadian rhythm, can be associated with an earlier onset of bipolar disorder 31 and a higher likelihood of experiencing a depressive episode at onset. 31 However, the major focus of environmental studies in bipolar disorder has been on traumatic and stressful life events in early childhood 32 and in adulthood. 33 The effects of such adverse events are complex, but on a broad level have been associated with earlier onset of bipolar disorder, a worse illness course, greater prevalence of psychotic symptoms, 34 substance misuse and psychiatric comorbidities, and a higher risk of suicide attempts. 32 35 Perhaps uniquely in bipolar disorder, evidence also indicates that positive life events associated with goal attainment can also increase the risk of developing elevated states. 36

Comorbidity

Bipolar disorder rarely manifests in isolation, with comorbidity rates indicating elevated lifetime risk of several co-occurring symptoms and comorbid disorders, particularly anxiety, attentional disorders, substance misuse disorders, and personality disorders. 37 38 The causes of such comorbidity can be varied and complex: they could reflect a mixed presentation artifactually separated by current diagnostic criteria; they might also reflect independent illnesses; or they might represent the downstream effects of one disorder increasing the risk of developing another disorder. 39 Anxiety disorders tend to occur before the frank onset of manic or hypomanic symptoms, suggesting that they could in part reflect prodromal symptoms that manifest early in the lifespan. 37 Similarly, subthreshold and syndromic symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder are also observed across the lifespan of people with bipolar disorder, but particularly in early onset bipolar disorder. 40 On the other hand, alcohol and substance misuse disorders occur more evenly before and after the onset of bipolar disorder, consistent with a more bidirectional causal association. 41

The association between bipolar disorder and comorbid personality disorders is similarly complex. Milder manifestations of persistent mood instability (cyclothymia) or low mood (dysthymia) have previously been considered to be temperamental variants of bipolar disorder, 42 but are now classified as related but separate disorders. In people with persistent emotional dysregulation, making the diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be particularly challenging, 43 since the boundaries between longstanding mood instability and phasic changes in mood state can be difficult to distinguish. While symptom overlap can lead to artificially inflated prevalence rates of personality disorders in bipolar disorder, 44 the elevated rates of most personality disorders in bipolar disorder, particularly those related to emotional instability, are likely reflective of an important clinical phenomenon that is understudied, particularly with regard to treatment implications. 45 In general, people with comorbidities tend to have greater symptom burden and functional impairment and have lower response rates to treatment. 46 47 Data on approaches to treat specific comorbid disorders in bipolar disorder are limited, 48 49 and clinicians are often left to rely on their clinical judgment. The most parsimonious approach is to treat primary illness as fully as possible before considering additional treatment options for remaining comorbid symptoms. For certain comorbidities, such as anxiety symptoms and disorders of attention, first line pharmacological treatment—namely, antidepressants and stimulants, should be used with caution, since they might increase the long term risks of mood switching or overall mood instability. 50 51

Like other major mental illnesses, bipolar disorder is also associated with an increased prevalence of common medical disorders such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and thyroid dysfunction. 52 These have been attributed to increase risk factors such as physical inactivity, poor nutrition, smoking, and increased use of addictive substances, 53 but some could also be consequences of specific treatments, such as the atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. 54 Along with poor access to care, this medical burden likely accounts for much of the increased standardized mortality (approximately 2.6 times higher) in people with bipolar disorder, 55 highlighting the need to utilize treatments with better long term side effect profiles, and the need for better integration with medical care.

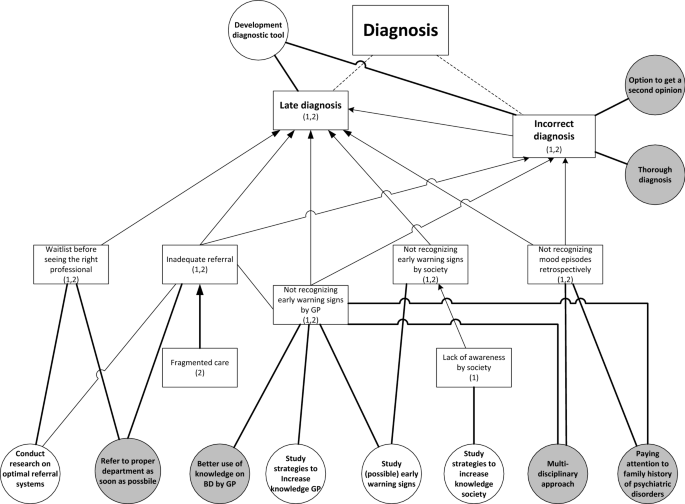

Precursors and prodromes: who develops bipolar disorder?

While more widespread screening and better accessibility to mental health providers should in principle shorten the time to diagnosis and treatment, early manifestation of symptoms in those who ultimately go on to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder is generally non-specific. 56 In particular, high risk offspring studies of adolescents with a parent with bipolar disorder have found symptoms of anxiety and attentional/disruptive disorders to be frequent in early adolescence, followed by higher rates of depression and sleep disturbance in later teenage years. 56 57 Subthreshold symptoms of mania, such as prolonged increases in energy, elated mood, racing thoughts, and mood lability are also more commonly found in children with prodromal symptoms (meta-analytic prevalence estimates ranging from 30-50%). 58 59 Still, when considered individually, none of these symptoms or disorders are sensitive or specific enough to accurately identify individuals who will transition to bipolar disorder. Ongoing approaches to consider these clinical factors together to improve accuracy have a promising but modest ability to identify people who will develop bipolar disorder, 60 emphasizing the need for further studies before implementation.

Screening for bipolar disorder

Manic episodes can vary from easily identifiable prototypical presentations to milder or less typical symptoms that can be challenging to diagnose. Ideally, a full diagnostic evaluation with access to close informants is performed on patients presenting to clinical care; however, evaluations can be hurried in routine clinical care, and the ability to recall previous episodes might be limited. In this context, the use of screening scales can be a helpful addition to clinical care, although screening scales must be regarded as an impetus for a confirmatory clinical interview rather than a diagnostic instrument by themselves. The two most widely used and openly available screening scales are the mood disorders questionnaire (based on the DSM-IV criteria for hypomania) 61 and the hypomania check list (HCL-32), 62 that represent a broader overview of symptoms proposed to be part of a broader bipolar spectrum.

Racial/ethnic disparities

Although community surveys using structured or semi-structured diagnostic instruments, have provided little evidence for variation across ethnic groups, 63 64 observational studies based on clinical diagnoses in healthcare settings have found a disproportionately higher rate of diagnosis of schizophrenia relative to bipolar disorder in black people. 65 Consistent with similar disparities seen across medicine, these differences in clinical diagnoses are likely influenced by a complex mix of varying clinical presentations, differing rates of comorbid conditions, poorer access to care, greater social and economic burden, as well as the potential effect of subtle biases of healthcare professionals. 65 While further research is necessary to identify driving factors responsible for diagnostic disparities, clinicians should be wary of making a rudimentary diagnosis in patients from marginalized backgrounds, ensuring comprehensive data gathering and a careful diagnostic formulation that incorporates shared decision making between patient and provider.

Bipolar disorder is a recurrent illness, but its longitudinal course is heterogeneous and difficult to predict. 46 66 The few available long term studies of BD-I and BD-II have found a consistent average rate of recurrence of 0.40 mood episodes per year in historical studies 67 and 0.44 mood episodes per year in more recent studies. 68 The median time to relapse is estimated to be 1.44 years, with higher relapse rates seen in BD-I (0.81 years) than in BD-II (1.63 years) and no differences observed with respect to age or sex. 1 2 In addition to focusing on episodes, an important development in research and clinical care of bipolar disorder has been the recognition of the burden of subsyndromal symptoms. Although milder in severity, these symptoms can be long lasting, functionally impairing, and can themselves be a risk factor for episode relapse. 69 Recent cohort studies have also found that a substantial proportion of patients with bipolar disorder (20-30%) continue to have poor outcomes even after receiving guideline based care. 46 70 Risk factors that contribute to this poor outcome include transdiagnostic indicators of adversity such as substance misuse, low educational attainment, socioeconomic hardship, and comorbid disorders. As expected, those with more severe past illness activity, including those with rapid cycling, were also more likely to remain symptomatically and psychosocially impaired. 46 71 72

The primary focus of treating bipolar disorder has been to manage the manic, mixed, or depressive episodes that present to clinical care and to subsequently prevent recurrence of future episodes. Owing to the relapse remitting nature of the illness, randomized controlled trials are essential to determine treatment efficacy, as the observation of clinical improvement could just represent the ebbs and flows of the natural history of the illness. In the United States, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) requires at least two large scale placebo controlled trials (phase 3) to show significant evidence of efficacy before approving a treatment. Phase 3 studies of bipolar disorder are generally separated into short term studies of mania (3-4 weeks), short term studies for bipolar depression (4-6 weeks), and longer term maintenance studies to evaluate prophylactic activity against future mood episodes (usually lasting one year). Although the most rigorous evaluation of phase 3 studies would be to require two broadly representative and independent randomized controlled trials, the FDA permits consideration of so called enriched design trials that follow participants after an initial response and tolerability has been shown to an investigational drug. Because of this initial selection, such trials can be biased against comparator agents, and could be less generalizable to patients seen in clinical practice.

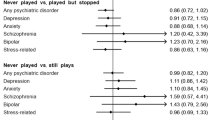

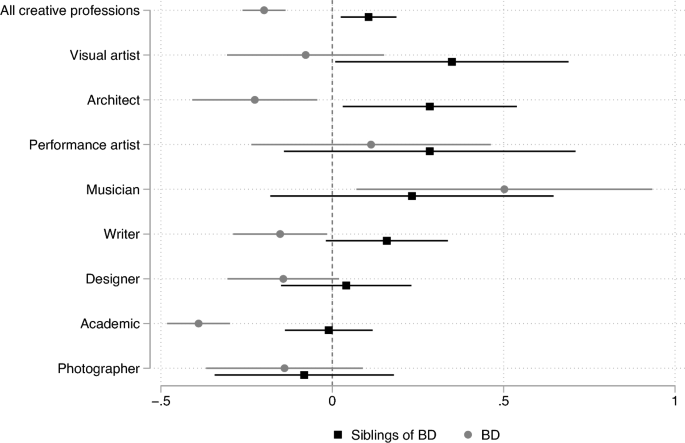

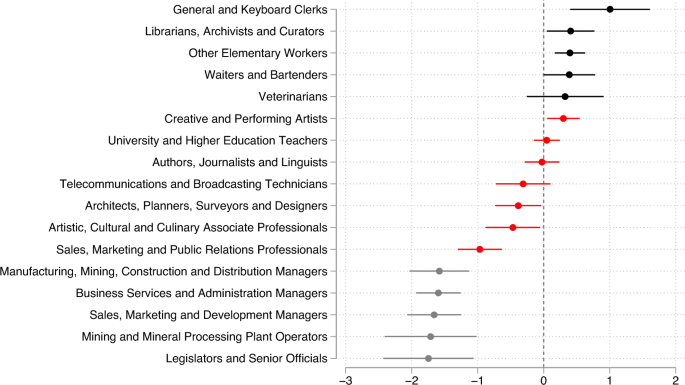

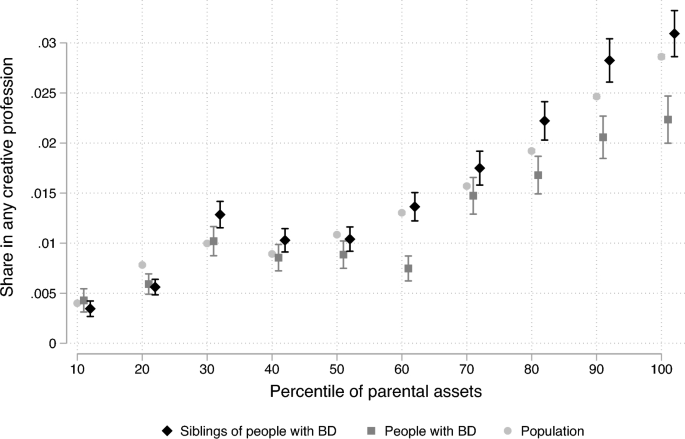

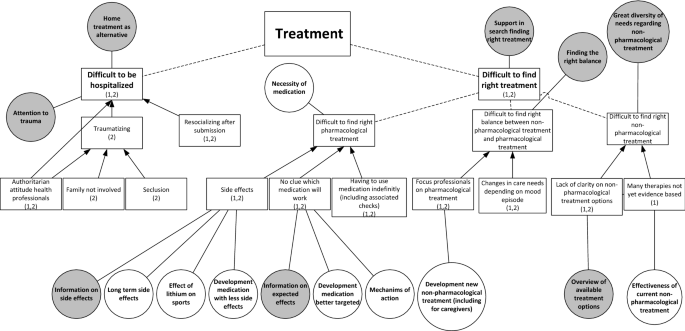

A summary of the agents approved by the FDA for treatment of bipolar disorder is in table 1 , which references the key clinical trials demonstrating efficacy. Figure 1 and supplementary table 1 are a comparison of treatments for mania, depression, and maintenance. Effect sizes reflect the odds ratios or relative risks of obtaining response (defined as ≥50% improvement from baseline) in cases versus controls and were extracted from meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials for bipolar depression 86 and maintenance, 94 as well as a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in bipolar mania. 73 Effect sizes are likely to be comparable for each phase of treatment, but not across the different phases, since methodological differences exist between the three meta-analytic studies.

FDA approved medications for bipolar disorder

- View inline

Summary of treatment response rates (defined as ≥50% improvement from baseline) of modern clinical trials for acute mania, acute bipolar depression, and long term recurrence. Meta-analytic estimates were extracted from recent meta-analyses or network meta-analyses of acute mania, 73 acute bipolar depression, 86 and bipolar maintenance studies 94

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Acute treatment of mania

As mania is characterized by impaired judgment, individuals can be at risk for engaging in high risk, potentially dangerous behaviors that can have substantial personal, occupational, and financial consequences. Therefore, treatment of mania is often considered a psychiatric emergency and is, when possible, best performed in the safety of an inpatient unit. While the primary treatment for mania is pharmacological, diminished insight can impede patients' willingness to accept treatment, emphasizing the significance of a balanced therapeutic approach that incorporates shared decision making frameworks as much as possible to promote treatment adherence.

The three main classes of anti-manic treatments are lithium, mood stabilizing anticonvulsants (divalproate and carbamazepine), and antipsychotic medications. Almost all antipsychotics are effective in treating mania, with the more potent dopamine D2 receptor antagonists such as risperidone and haloperidol demonstrating slightly higher efficacy ( fig 1 ). 73 In the United States, the FDA has approved the use of all second generation antipsychotics for treating mania except for lurasidone and brexpriprazole. Compared with mood stabilizing medications, second generation antipsychotics have a faster onset of action, making them a first line treatment for more severe manic symptoms that require rapid treatment. 99 The choice of which specific second generation antipsychotic to use depends on a balance of efficacy, tolerability concerns, and cost considerations (see table 1 ). Notably, the FDA has placed a black box warning on all antipsychotics for increasing the risk of cerebral vascular accidents in the elderly. 100 While this was primarily focused on the use of antipsychotics in dementia, this likely class effect should be taken into account when considering the use of antipsychotics in the elderly.

Traditional mood stabilizers, such as lithium, divalproate, and carbamazepine are also effective in the treatment of active mania ( fig 1 ). Since lithium also has a robust prophylactic effect (see section on prevention of mood episodes below) it is often recommended as first line treatment and can be considered as monotherapy when rapid symptom reduction is not clinically indicated. On the other hand, other anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine, gabapentin, topiramate, and oxcarbazepine have not been found to be effective for the treatment of mania or mixed episodes. 101 Although the empirical evidence for polypharmacy is limited, 102 combination treatment in acute mania, usually consisting of a mood stabilizer and a second generation antipsychotic, is commonly used in clinical practice despite the higher burden of side effects. Following resolution of an acute mania, consideration should be given to transitioning to monotherapy with an agent with proven prophylactic activity.

Pharmacological approaches to bipolar depression

Depressed episodes are usually more common than mania or hypomania, 103 104 and often represent the primary reason for individuals with bipolar disorder to seek treatment. Nevertheless, because early antidepressant randomized controlled trials did not distinguish between unipolar and bipolar depressive episodes, it has only been in the past two decades that large scale randomized controlled trials have been conducted specifically for bipolar depression. As such trials are almost exclusively funded by pharmaceutical companies, they have focused on the second generation antipsychotics and newer anticonvulsants still under patent. These trials have shown moderate but robust effects for most recent second generation antipsychotics, five of which have received FDA approval for treating bipolar depression ( table 1 ). No head-to-head trials have been conducted among these agents, so the choice of medication depends on expected side effects and cost considerations. For example, quetiapine has robust antidepressant efficacy data but is associated with sedation, weight gain, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. 105 Other recently approved medications such as lurasidone, cariprazine, and lumateperone have better side effect profiles but show more modest antidepressant activity. 106

Among the mood stabilizing anticonvulsants, lamotrigine has limited evidence for acute antidepressant activity, 107 possibly owing to the need for an 8 week titration to reach the full dose of 200 mg. However, as discussed below, lamotrigine can still be considered for mild to moderate acute symptoms owing to its generally tolerable side effect profile and proven effectiveness in preventing the recurrence of depressive episodes. Divalproate and carbamazepine have some evidence of being effective antidepressants in small studies, but as there has been no large scale confirmatory study, they should be considered second or third line options. 86 Lithium has been studied for the treatment of bipolar depression as a comparator to quetiapine and was not found to have a significant acute antidepressant effect. 88

Antidepressants

Owing to the limited options of FDA approved medications for bipolar depression and concerns of metabolic side effects from long term second generation antipsychotic use, clinicians often resort to the use of traditional antidepressants for the treatment of bipolar depression 108 despite the lack of FDA approval for such agents. Indeed, recent randomized clinical trials of antidepressants in bipolar depression have not shown an effect for paroxetine, 89 109 bupropion, 109 or agomelatine. 110 Beyond the question of efficacy, another concern regarding antidepressants in bipolar disorder is their potential to worsen the course of illness by either promoting mixed or manic symptoms or inducing more subtle degrees of mood instability and cycle acceleration. 111 However, the risk of switching to full mania while being treated with mood stabilizers appears to be modest, with a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and clinical cohort studies showing the rates of mood switching over an average follow-up of five months to be approximately 15.3% in people with bipolar disorder treated on antidepressants compared with 13.8% in those without antidepressant treatment. 111 The risk of switching appears to be higher in the first 1-2 years of treatment in people with BD-I, and in those treated with a tricyclic antidepressant 112 or the dual reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine. 113 Overall, while the available data have methodological limitations, most guidelines do not recommend the use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder, or recommend them only after agents with more robust evidence have been tried. That they remain so widely used despite the equivocal evidence base reflects the unmet need for treatment of depression, concerns about the long term side effects of second generation antipsychotics, and the challenges of changing longstanding prescribing patterns.

Pharmacological approaches to prevention of recurrent episodes

Following treatment of the acute depressive or manic syndrome, the major focus of treatment is to prevent future episodes and minimize interepisodic subsyndromal symptoms. Most often, the medication that has been helpful in controlling the acute episode can be continued for prevention, particularly if clinical trial evidence exists for a maintenance effect. To show efficacy for prevention, studies must be sufficiently long to allow the accumulation of future episodes to occur and be potentially prevented by a therapeutic intervention. However, few long term treatment studies exist and most have utilized enriched designs that likely favor the drug seeking regulatory approval. As shown in figure 1 , meta-analyses 94 show prophylactic effect for most (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole, asenapine) but not all (lurasidone, paliperidone) recently approved second generation antipsychotics. The effect sizes are generally comparable with monotherapy (odds ratio 0.42, 95% confidence interval 0.34 to 0.5) or as adjunctive therapy (odds ratio 0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.25 to 0.55). 94 Recent studies of lithium, which have generally used it as a (non-enriched) comparator drug, show a comparable protective effect (odds ratio 0.46, 95% confidence interval 0.28 to 0.75). 94 Among the mood stabilizing anticonvulsant drugs, a prophylactic effect has also been found for both divalproate and lamotrigine ( fig 1 and supplementary table 1), although only the latter has been granted regulatory approval for maintenance treatment. While there are subtle differences in effect sizes in drugs approved for maintenance ( fig 1 and table 1 ), the overlapping confidence intervals and methodological differences between studies prevent a strict comparison of the effect measures.

Guidelines often recommend lithium as a first line agent given its consistent evidence of prophylaxis, even when tested as the disadvantaged comparator drug in enriched drug designs. Like other medications, lithium has a unique set of side effects and ultimately the decision about which drug to use among those which are efficacious should be a decision carefully weighed and shared between patient and provider. The decision might be re-evaluated after substantial experience with the medication or at different stages in the long term treatment of bipolar disorder (see table 1 ).

Psychotherapeutic approaches

The frequent presence of residual symptoms, often associated with psychosocial and occupational dysfunction, has led to renewed interest in psychotherapeutic and psychosocial approaches to bipolar disorder. Given the impairment of judgment seen in mania, psychotherapy has more of a supportive and educational role in the treatment of mania, whereas it can be more of a primary focus in the treatment of depressive states. On a broad level, psychotherapeutic approaches effective for acute depression, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, behavioral activation, and mindfulness based strategies, can also be recommended for acute depressive states in individuals with bipolar disorder. 114 Evidence for more targeted psychotherapy trials for bipolar disorder is more limited, but meta-analyses have found evidence for decreased recurrence (odds ratio 0.56; 95% confidence interval 0.43 to 0.74) 115 and improvement of subthreshold interepisodic depressive and manic symptoms with cognitive behavioral therapy, family based therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and psychoeducation. 115 Recent investigations have also focused on targeted forms of psychotherapy to improve cognition 116 117 118 as well as psychosocial and occupational functioning. 119 120 Although these studies show evidence of a moderate effect, they remain preliminary, methodologically diverse, and require replication on a larger scale. 121

The implementation of evidence based psychotherapy as a treatment faces several challenges, including clinical training, fidelity monitoring, and adequate reimbursement. Novel approaches, leveraging the greater tractability of digital tools 122 and allied healthcare workers, 123 are promising means of lessening the implementation gap; however, these approaches require validation and evidence of clinical utility similar to traditional methods.

Neurostimulation approaches

For individuals with bipolar disorder who cannot tolerate or do not respond well to standard pharmacotherapy or psychotherapeutic approaches, neurostimulation techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or electric convulsive therapy should be considered as second or third line treatments. Electric convulsive therapy has shown response rates of approximately 60-80% in severe acute depressions 124 125 and 50-60% in cases with treatment resistant depression. 126 These response rates compare favorably with those of pharmacological treatment, which are likely to be closer to ~50% and ~30% in subjects with moderate to severe depression and treatment resistant depression, respectively. 127 Although the safety of electric convulsive therapy is well established, relatively few medical centers have it available, and its acceptability is limited by cognitive side effects, which are usually short term, but which can be more significant with longer courses and with bilateral electrode placement. 128 While there have been fewer studies of electric convulsive therapy for bipolar depression compared with major depressive disorder, it appears to be similarly effective and might show earlier response. 129 Anecdotal evidence also suggests electric convulsive therapy that is useful in refractory mania. 130

Compared with electric convulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has no cognitive side effects and is generally well tolerated. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation acts by generating a magnetic field to depolarize local neural tissue and induce excitatory or inhibitory effects depending on the frequency of stimulation. The most studied FDA approved form of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation applies high frequency (10 Hz) excitatory pulses to the left prefrontal cortex for 30-40 minutes a day for six weeks. 131 Like electric convulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has been primarily studied in treatment resistant depression and has been found to have moderate effect, with about one third of patients having a significant treatment response compared with those treated with pharmacotherapy. 131 Recent innovations in transcranial magnetic stimulation have included the use of a novel, larger coil to stimulate a larger degree of the prefrontal cortex (deep transcranial magnetic stimulation), 132 and a shortened (three minutes), higher frequency intermittent means of stimulation known as theta burst stimulation that appears to be comparable to conventional (10 Hz) repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. 133 A preliminary trial has recently assessed a new accelerated protocol of theta burst stimulation marked by 10 sessions a day for five days. It found that theta burst stimulation had a greater effect on people with treatment resistant depression compared with treatment as usual, although larger studies are needed to confirm these findings. 134

Conventional repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (10 Hz) studies in bipolar disorder have been limited by small sample sizes but have generally shown similar effects compared with major depressive disorder. 135 However, a proof of concept study of single session theta burst stimulation did not show efficacy in bipolar depression, 136 reiterating the need for specific trials for bipolar depression. Given the lack of such trials in bipolar disorder, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation should be considered a potentially promising but as yet unproven treatment for bipolar depression.

The other major form of neurostimulation studied in both unipolar and bipolar depression is transcranial direct current stimulation, an easily implemented method of delivering a low amplitude electrical current to the prefrontal area of the brain that could lead to local changes in neuronal excitability. 137 Like repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation is well tolerated and has been mostly studied in unipolar depression, but has not yet generated sufficient evidence to be approved by a regulatory agency. 138 Small studies have been performed in bipolar depression, but the results have been mixed and require further research before use in clinical settings. 137 138 139 Finally, the evidence for more invasive neurostimulation studies such as vagal nerve stimulation and deep brain stimulation remains extremely limited and is currently insufficient for clinical use. 140 141

Treatment resistance in bipolar disorder

As in major depressive disorder, the use of term treatment resistance in bipolar disorder is controversial since differentiating whether persistent symptoms are caused by low treatment adherence, poor tolerability, the presence of comorbid disorders, or are the result of true treatment resistance, is an essential but often challenging clinical task. Treatment resistance should only be considered after two or three trials of evidence based monotherapy, adjunctive therapy, or both. 142 In difficult-to-treat mania, two or more medications from different mechanistic classes are typically used, with electric convulsive therapy 143 and clozapine 144 being considered if more conventional anti-manic treatments fail. In bipolar depression, it is common to combine antidepressants with anti-manic agents, despite limited evidence for efficacy. 145 Adjunctive therapies such as bright light therapy, 146 the dopamine D2/3 receptor agonist pramipexole, 147 and ketamine 148 149 have shown promising results in small open label trials that require further study.

Treatment considerations to reduce suicide in bipolar disorder

The risk of completed suicide is high across the subtypes of bipolar disorder, with estimated rates of 10-15% across the lifespan. 150 151 152 Lifetime rates of suicide attempts are much higher, with almost half of all individuals with bipolar disorder reporting at least one attempt. 153 Across a population and, often within individuals, the causes of suicide attempts and completed suicides are likely to be multifactorial, 154 affected by various risk factors, such as symptomatic illness, environmental stressors, comorbidities (particularly substance misuse), trait impulsivity, interpersonal conflict, loneliness, or socioeconomic distress. 155 156 Risk is highest in depressive and dysphoric/mixed episodes 157 158 and is particularly high in the transitional period following an acute admission to hospital. 159 Among the available treatments, lithium has potential antisuicidal properties. 160 However, since suicide is a rare event, with very few to zero suicides within a typical clinical trial, moderate evidence for this effect emerges only in the setting of meta-analyses of clinical trials. 160 Several observational studies have shown lower mortality in patients on lithium treatment, 161 but such associations might not be causal, since lithium is potentially fatal in overdose and is often avoided by clinicians in patients at high risk of suicide.

The challenge of studying scarce events has led most studies to focus on the reduction of the more common phenomena of suicidal ideation and behavior as a proxy for actual suicides. A recent such multisite study of the Veterans Affairs medical system included a mixture of unipolar and bipolar disorder and was stopped prematurely for futility, indicating no overall effect of moderate dose lithium. 162 Appropriate limitations of this study have been noted, 163 164 including difficulties in recruitment, few patients with bipolar disorder (rather than major depressive disorder), low levels of compliance with lithium therapy, high rates of comorbidity, and a follow-up of only one year. Nevertheless, while the body of evidence suggests that lithium has a modest antisuicidal effect, its degree of protection and utility in complex patients with comorbidities and multiple risk factors remain matters for further study. Treatment of specific suicidal risk in patients with bipolar disorder must therefore also incorporate broader interventions based on the individual’s specific risk factors. 165 Such an approach would include societal interventions like means restriction 166 and a number of empirically tested suicide focused psychotherapy treatments. 167 168 Unfortunately, the availability of appropriate training, expertise, and care models for such treatments remains limited, even in higher income countries. 169

More scalable solutions, such as the deployment of shortened interventions via digital means could help to overcome this implementation gap; however, the effectiveness of such approaches cannot be assumed and requires empirical testing. For example, a recent large scale randomized controlled trial of an abbreviated online dialectical behavioral therapy skills training program was paradoxically associated with slightly increased risk of self-harm. 170

Treatment consideration in BD-II and bipolar spectrum conditions

Because people with BD-II primarily experience depressive symptoms and appear less likely to switch mood states compared with individuals with BD-I, 50 171 there has been a greater acceptance of the use of antidepressants in BD-II depression, including as monotherapy. 172 However, caution should be exercised when considering the use of antidepressants without a mood stabilizer in patients with BD-II who might also experience high rates of mood instability and rapid cycling. Such individuals can instead respond better to newer second generation antipsychotic agents such as quetiapine 173 and lumateperone, 93 which are supported by post hoc analyses of these more recent clinical trials with more BD-II patients. In addition, despite the absence of randomized controlled trials, open label studies have suggested that lithium and other mood stabilizers can have similar efficacy in BD-II, especially in the case of lamotrigine. 174

Psychotherapeutic approaches such as psychoeducation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy have been found to be helpful 115 and can be considered as the primary form of treatment for BD-II in some patients, although in most clinical scenarios BD-II is likely to occur in conjunction with psychopharmacology. While it can be tempting to consider BD-II a milder variant of BD-I, high rates of comorbid disorders, rapid cycling, and adverse consequences such as suicide attempts 175 176 highlight the need for clinical caution and the provision of multimodal treatment, focusing on mood improvement, emotional regulation, and better psychosocial functioning.

Precision medicine: can it be applied to improve the care of bipolar disorder?

The recent focus on precision medicine approaches to psychiatric disorders seeks to identify clinically relevant heterogeneity and identify characteristics at the level of the individual or subgroup that can be leveraged to identify and target more efficacious treatments. 1 177 178

The utility of such an approach was originally shown in oncology, where a subset of tumors had gene expression or DNA mutation signatures that could predict response to treatments specifically designed to target the aberrant molecular pathway. 179 While much of the emphasis of precision medicine has been on the eventual identification of biomarkers utilizing high throughput approaches (genetics and other “omics” based measurements), the concept of precision medicine is arguably much broader, encompassing improvements in measurement, potentially through the deployment of digital tools, as well as better conceptualization of contextual, cultural, and socioeconomic mechanisms associated with psychopathology. 180 181 Ultimately, the goal of precision psychiatry is to identify and target driving mechanisms, be they molecular, physiological, or psychosocial in nature. As such, precision psychiatry seeks what researchers and clinicians have often sought: to identify clinically relevant heterogeneity to improve prediction of outcomes and increase the likelihood of therapeutic success. The novelty being not so much the goals of the overarching approach, but the increasing availability of large samples, novel digital tools, analytical advances, and an increasing armamentarium of biological measurements that can be deployed at scale. 177

Although not unique to bipolar disorder, several clinical decision points along the life course of bipolar disorder would benefit from a precision medicine approach. For example, making an early diagnosis is often not possible based on clinical symptoms alone, since such symptoms are usually non-specific. A precision medicine approach could also be particularly relevant in helping to identify subsets of patients for whom the use of antidepressants could be beneficial or harmful. Admittedly, precision medicine approaches to bipolar disorder are still in their infancy, and larger, clinically relevant, longitudinal, and reliable phenotypes are needed to provide the infrastructure for precision medicine approaches. Such data remain challenging to obtain at scale, leading to renewed efforts to utilize the extant clinical infrastructure and electronic medical records to help emulate traditional longitudinal analyses. Electronic medical records can help provide such data, but challenges such as missingness, limited quality control, and potential biases in care 182 need to be resolved with carefully considered analytical designs. 183

Emerging treatments

Two novel atypical antipsychotics, amilsupride and bifeprunox, are currently being tested in phase 3 trials ( NCT05169710 and NCT00134459 ) and could gain approval for bipolar depression in the near future if these pivotal trials show a significant antidepressant effect. These drugs could offer advantages such as greater antidepressant effects, fewer side effects, and better long term tolerability, but these assumptions must be tested empirically. Other near term possibilities include novel rapid antidepressant treatments, such as (es)ketamine that putatively targets the glutamatergic system, and has been recently approved for treatment resistant depression, but which have not yet been tested in phase 3 studies in bipolar depression. Small studies have shown comparable effects of intravenous ketamine, 149 184 in bipolar depression with no short term evidence of increased mood switching or mood instability. Larger phase 2 studies ( NCT05004896 ) are being conducted which will need to be followed by larger phase 3 studies. Other therapies targeting the glutamatergic system have generally failed phase 3 trials in treatment resistant depression, making them unlikely to be tested in bipolar depression. One exception could be the combination of dextromethorphan and its pharmacokinetic (CYP2D6) inhibitor bupropion, which was recently approved for treatment resistant depression but has yet to be tested in bipolar depression. Similarly, the novel GABAergic compound zuranolone is currently being evaluated by the FDA for the treatment of major depressive disorder and could also be subsequently studied in bipolar depression.

Unfortunately, given the general efficacy for most patients of available treatments, few scientific and financial incentives exist to perform large scale studies of novel treatment in mania. Encouraging results have been seen in small studies of mania with the selective estrogen receptor modulator 185 tamoxifen and its active metabolite endoxifen, both of which are hypothesized to inhibit protein kinase C, a potential mechanistic target of lithium treatment. These studies remain small, however, and anti-estrogenic side effects have potentially dulled interest in performing larger studies.

Finally, several compounds targeting alternative pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in bipolar disorder have been trialed in phase 2 academic studies. The most studied has been N -acetylcysteine, a putative mitochondrial modulator, which initially showed promising results only to be followed by null findings in larger more recent studies. 186 Similarly, although small initial studies of anti-inflammatory agents provided impetus for further study, subsequent phase 2 studies of the non-steroidal agent celecoxib, 187 the anti-inflammatory antibiotic minocycline, 187 and the antibody infliximab (a tumor necrosis factor antagonist) 188 have not shown efficacy for bipolar depression. Secondary analyses have suggested that specific anti-inflammatory agents might be effective only for a subset of patients, such as those with elevated markers of inflammation or a history of childhood adversity 189 ; however, such hypotheses must be confirmed in adequately powered independent studies.

Several international guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder have been published in the past decade, 102 190 191 192 providing a list of recommended treatments with efficacy in at least one large randomized controlled trial. Since effect sizes tend to be moderate and broadly comparable across classes, all guidelines allow for significant choice among first line agents, acknowledging that clinical characteristics, such as history of response or tolerability, severity of symptoms, presence of mixed features, or rapid cycling can sometimes over-ride guideline recommendations. For acute mania requiring rapid treatment, all guidelines prioritize the use of second generation antipsychotics such as aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, asenapine, and cariprazine. 102 192 193 Combination treatment is considered based on symptom severity, tolerability, and patient choice, with most guidelines recommending lithium or divalproate along with a second generation antipsychotic for mania with psychosis, severe agitation, or prominent mixed symptoms. While effective, haloperidol is usually considered a second choice option owing to its propensity to cause extrapyramidal symptoms. 102 192 193 Uniformly, all guidelines agree on the need to taper antidepressants in manic or mixed episodes.

For maintenance treatment, guidelines are generally consistent in recommending lithium if tolerated and without relative contraindications, such as baseline renal disease. 194 The second most recommended maintenance treatment is quetiapine, followed by aripiprazole for patients with prominent manic episodes and lamotrigine for patients with predominant depressive episodes. 194 Most guidelines recommend considering prophylactic properties when initially choosing treatment for acute manic episodes, although others suggests that acute maintenance treatments can be cross tapered with maintenance medications after several months of full reponse. 193

For bipolar depression, recent guidelines recommend specific second generation antipsychotics such as quetiapine, lurasidone, and cariprazine 102 192 193 For more moderate symptoms, consideration is given to first using lamotrigine and lithium. Guidelines remain cautious about the use of antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, or bupropion) in patients with BP-I, restricting them to second or third line treatments and always in the context of an anti-manic agent. However, for patients with BP-II and no rapid cycling, several guidelines allow for the use of carefully monitored antidepressant monotherapy.

Bipolar disorder is a highly recognizable syndrome with many effective treatment options, including the longstanding gold standard therapy lithium. However, a significant proportion of patients do not respond well to current treatments, leading to negative consequences, poor quality of life, and potentially shortened lifespan. Several novel treatments are being developed but limited knowledge of the biology of bipolar disorder remains a major challenge for novel drug discovery. Hope remains that the insights of genetics, neuroimaging, and other investigative modalities could soon be able to inform the development of rational treatments aimed to mitigate the underlying pathophysiology associated with bipolar disorder. At the same time, however, efforts are needed to bridge the implementation gap and provide truly innovative and integrative care for patients with bipolar disorder. 195 Owing to the complexity of bipolar disorder, few patients can be said to be receiving optimized care across the various domains of mental health that are affected in those with bipolar disorder. Fortunately, the need for improvement is now well documented, 196 and concerted efforts at the scale necessary to be truly innovative and integrative are now on the horizon.

Questions for future research

Among adolescents and young adults who manifest common mental disorders such as anxiety or depressive or attentional disorders, who will be at high risk for developing bipolar disorder?

Can we predict the outcomes for patients following a first manic or hypomanic episode? This will help to inform who will require lifelong treatment and who can be tapered off medications after sustained recovery.

Are there reliable clinical features and biomarkers that can sufficiently predict response to specific medications or classes of medication?

What are the long term consequences of lifelong treatments with the major classes of medications used in bipolar disorder? Can we predict and prevent medical morbidity caused by medications?

Can we understand in a mechanistic manner the pathophysiological processes that lead to abnormal mood states in bipolar disorder?

Series explanation: State of the Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason they are written predominantly by US authors

Contributors: FSG performed the planning, conduct, and reporting of the work described in the article. FSG accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: I have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient involvement: FSG discussed of the manuscript, its main points, and potential missing points with three patients in his practice who have lived with longstanding bipolar disorder. These additional viewpoints were incorporated during the drafting of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ . Falret’s discovery: the origin of the concept of bipolar affective illness. Translated by M. J. Sedler and Eric C. Dessain. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140:1127-33. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.9.1127 OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Translated by R. Mary Barclay from the Eighth German. Edition of the ‘Textbook of Psychiatry.’ 1921.

- Merikangas KR ,

- Akiskal HS ,

- Koukopoulos A ,

- Jongsma HE ,

- Kirkbride JB ,

- Rowland TA ,

- Kessler RC ,

- Kazdin AE ,

- Aguilar-Gaxiola S ,

- WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators

- Bergen SE ,

- Kuja-Halkola R ,

- Larsson H ,

- Lichtenstein P

- Smoller JW ,

- Lichtenstein P ,

- Sjölander A ,

- Mullins N ,

- Forstner AJ ,

- O’Connell KS ,

- Palmer DS ,

- Howrigan DP ,

- Chapman SB ,

- Pirooznia M ,

- Murray GK ,

- McGrath JJ ,

- Hickie IB ,

- ↵ Mostafavi H, Harpak A, Agarwal I, Conley D, Pritchard JK, Przeworski M. Variable prediction accuracy of polygenic scores within an ancestry group. Loos R, Eisen MB, O’Reilly P, eds. eLife 2020;9:e48376. doi: 10.7554/eLife.48376 OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Westlye LT ,

- van Erp TGM ,

- Costa Rica/Colombia Consortium for Genetic Investigation of Bipolar Endophenotypes

- Pauling M ,

- ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group

- Schnack HG ,

- Ching CRK ,

- ENIGMA Bipolar Disorders Working Group

- Goltermann J ,

- Hermesdorf M ,

- Dannlowski U

- Gurholt TP ,

- Suckling J ,

- Lennox BR ,

- Bullmore ET

- Marangoni C ,

- Hernandez M ,

- Achtyes ED ,

- Agnew-Blais J ,

- Gilman SE ,

- Upthegrove R ,

- ↵ Etain B, Aas M. Childhood Maltreatment in Bipolar Disorders. In: Young AH, Juruena MF, eds. Bipolar Disorder: From Neuroscience to Treatment . Vol 48. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Springer International Publishing; 2020:277-301. doi: 10.1007/7854_2020_149

- Johnson SL ,

- Weinberg BZS

- Stinson FS ,

- Costello CG

- Klein & Riso LP DN

- Sandstrom A ,

- Perroud N ,

- de Jonge P ,

- Bunting B ,

- Nierenberg AA

- Hantouche E ,

- Vannucchi G

- Zimmerman M ,

- Ruggero CJ ,

- Chelminski I ,

- Leverich GS ,

- McElroy S ,

- Mignogna KM ,

- Balling C ,

- Dalrymple K

- Kappelmann N ,

- Stokes PRA ,

- Jokinen T ,

- Baldessarini RJ ,

- Faedda GL ,

- Offidani E ,

- Viktorin A ,

- Launders N ,

- Osborn DPJ ,

- Roshanaei-Moghaddam B ,

- De Hert M ,

- Detraux J ,

- van Winkel R ,

- Lomholt LH ,

- Andersen DV ,

- Sejrsgaard-Jacobsen C ,

- Skjelstad DV ,

- Gregersen M ,

- Søndergaard A ,

- Brandt JM ,

- Van Meter AR ,

- Youngstrom EA ,

- Taylor RH ,

- Ulrichsen A ,

- Strawbridge R

- Hafeman DM ,

- Merranko J ,

- Hirschfeld RM ,

- Williams JB ,

- Spitzer RL ,

- Adolfsson R ,

- Benazzi F ,

- Regier DA ,

- Johnson KR ,

- Akinhanmi MO ,

- Biernacka JM ,

- Strakowski SM ,

- Goldberg JF ,

- Schettler PJ ,

- Coryell W ,

- Scheftner W ,

- Endicott J ,

- Zarate CA Jr . ,

- Matsuda Y ,

- Fountoulakis KN ,

- Zarate CA Jr .

- Bowden CL ,

- Brugger AM ,

- The Depakote Mania Study Group

- Calabrese JR ,

- Depakote ER Mania Study Group

- Weisler RH ,

- Kalali AH ,

- Ketter TA ,

- SPD417 Study Group

- Keck PE Jr . ,

- Cutler AJ ,

- Caffey EM Jr . ,

- Grossman F ,

- Eerdekens M ,

- Jacobs TG ,

- Grundy SL ,

- The Olanzipine HGGW Study Group

- Versiani M ,

- Ziprasidone in Mania Study Group

- Sanchez R ,

- Aripiprazole Study Group

- McIntyre RS ,

- Panagides J

- Calabrese J ,

- McElroy SL ,

- EMBOLDEN I (Trial 001) Investigators

- EMBOLDEN II (Trial D1447C00134) Investigators

- Lamictal 606 Study Group

- Lamictal 605 Study Group

- Keramatian K ,

- Chakrabarty T ,

- Nestsiarovich A ,

- Gaudiot CES ,

- Neijber A ,

- Hellqvist A ,

- Paulsson B ,

- Trial 144 Study Investigators

- Schwartz JH ,

- Szegedi A ,

- Cipriani A ,

- Salanti G ,

- Dorsey ER ,

- Rabbani A ,

- Gallagher SA ,

- Alexander GC

- Cerqueira RO ,

- Yatham LN ,

- Kennedy SH ,

- Parikh SV ,

- Højlund M ,

- Andersen K ,

- Correll CU ,

- Ostacher M ,

- Schlueter M ,

- Geddes JR ,

- Mojtabai R ,

- Nierenberg AA ,

- Goodwin GM ,

- Agomelatine Study Group

- Vázquez G ,

- Baldessarini RJ

- Altshuler LL ,

- Cuijpers P ,

- Miklowitz DJ ,

- Efthimiou O ,

- Furukawa TA ,

- Strawbridge R ,

- Tsapekos D ,

- Hodsoll J ,

- Vinberg M ,

- Kessing LV ,

- Forman JL ,

- Miskowiak KW

- Lewandowski KE ,

- Sperry SH ,

- Torrent C ,

- Bonnin C del M ,

- Martínez-Arán A ,

- Bonnín CM ,

- Tamura JK ,

- Carvalho IP ,

- Leanna LMW ,

- Karyotaki E ,

- Individual Patient Data Meta-Analyses for Depression (IPDMA-DE) Collaboration

- Vipulananthan V ,

- Hurlemann R ,

- UK ECT Review Group

- Haskett RF ,

- Mulsant B ,

- Trivedi MH ,

- Wisniewski SR ,

- Espinoza RT ,

- Vazquez GH ,

- McClintock SM ,

- Carpenter LL ,

- National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group ,

- American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments

- Levkovitz Y ,

- Isserles M ,

- Padberg F ,

- Blumberger DM ,

- Vila-Rodriguez F ,

- Thorpe KE ,

- Williams NR ,

- Sudheimer KD ,

- Bentzley BS ,

- Konstantinou G ,

- Toscano E ,

- Husain MM ,

- McDonald WM ,

- International Consortium of Research in tDCS (ICRT)

- Sampaio-Junior B ,

- Tortella G ,

- Borrione L ,

- McAllister-Williams RH ,

- Gippert SM ,

- Switala C ,

- Bewernick BH ,

- Hidalgo-Mazzei D ,

- Mariani MG ,

- Fagiolini A ,

- Swartz HA ,

- Benedetti F ,

- Barbini B ,

- Fulgosi MC ,

- Burdick KE ,

- Diazgranados N ,

- Ibrahim L ,

- Brutsche NE ,

- Sinclair J ,

- Gerber-Werder R ,

- Miller JN ,

- Vázquez GH ,

- Franklin JC ,

- Ribeiro JD ,

- Turecki G ,

- Gunnell D ,

- Hansson C ,

- Pålsson E ,

- Runeson B ,

- Pallaskorpi S ,

- Suominen K ,

- Ketokivi M ,

- Hadzi-Pavlovic D ,

- Stanton C ,

- Lewitzka U ,

- Severus E ,

- Müller-Oerlinghausen B ,

- Rogers MP ,

- Li+ plus Investigators

- Manchia M ,

- Michel CA ,

- Auerbach RP

- Altavini CS ,

- Asciutti APR ,

- Solis ACO ,

- Casañas I Comabella C ,

- Riblet NBV ,

- Young-Xu Y ,

- Shortreed SM ,

- Rossom RC ,

- Amsterdam JD ,

- Brunswick DJ

- Gustafsson U ,

- Marangell LB ,

- Bernstein IH ,

- Karanti A ,

- Kardell M ,

- Collins FS ,

- Armstrong K ,

- Concato J ,

- Singer BH ,

- Ziegelstein RC

- ↵ Holmes JH, Beinlich J, Boland MR, et al. Why Is the Electronic Health Record So Challenging for Research and Clinical Care? Methods Inf Med 2021;60(1-02):32-48. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1731784

- García Rodríguez LA ,

- Cantero OF ,

- Martinotti G ,

- Dell’Osso B ,

- Di Lorenzo G ,

- REAL-ESK Study Group

- Palacios J ,

- DelBello MP ,

- Husain MI ,

- Chaudhry IB ,

- Subramaniapillai M ,

- Jones BDM ,

- Daskalakis ZJ ,

- Carvalho AF ,

- ↵ Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition Recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2016;30:495-553. doi: 10.1177/0269881116636545 OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Verdolini N ,

- Del Matto L ,

- Regeer EJ ,

- Hoogendoorn AW ,

- Harris MG ,

- WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 08 February 2021

Bipolar I disorder: a qualitative study of the viewpoints of the family members of patients on the nature of the disorder and pharmacological treatment non-adherence

- Nasim Mousavi 1 ,

- Marzieh Norozpour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8894-9178 1 ,

- Zahra Taherifar 2 ,

- Morteza Naserbakht 3 &

- Amir Shabani 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 21 , Article number: 83 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Bipolar disorder is a common psychiatric disorder with a massive psychological and social burden. Research indicates that treatment adherence is not good in these patients. The families’ knowledge about the disorder is fundamental for managing their patients’ disorder. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the knowledge of the family members of a sample of Iranian patients with bipolar I disorder (BD-I) and to explore the potential reasons for treatment non-adherence.

This study was conducted by qualitative content analysis. In-depth interviews were held and open-coding inductive analysis was performed. A thematic content analysis was used for the qualitative data analysis.