Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 15 June 2020

How STRANGE are your study animals?

- Michael M. Webster 0 &

- Christian Rutz 1

Michael M. Webster is a lecturer in the School of Biology, University of St Andrews, UK.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Christian Rutz is a professor in the School of Biology, University of St Andrews, UK, and worked on this article while he was the 2019–2020 Grass Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

A hawksbill sea turtle ( Eretmochelys imbricata ) tagged with a satellite transmitter. Credit: Pete Oxford/NPL

Ten years ago this week, researchers pointed out that many important findings in human experimental psychology cannot be generalized because study participants are predominantly drawn from a small, unrepresentative subset of the world’s population: societies that are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) 1 . Mounting evidence suggests that there could be similar sampling problems in research on animals. Behavioural studies of a wide range of species — from insects to primates — could be affected, with researchers testing individuals that are not fully representative of the wider populations they seek to understand. For example, certain sampling protocols are likely to trap the boldest animals, potentially skewing experimental results 2 .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 582 , 337-340 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01751-5

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. Behav. Brain Sci. 33 , 61–83 (2010).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Biro, P. A. & Dingemanse, N. J. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24 , 66–67 (2009).

Alfred, J. & Baldwin, I. T. eLife 4 , e06956 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Morton, F. B., Lee, P. C. & Buchanan-Smith, H. M. Anim. Cogn. 16 , 677–684 (2013).

Bateson, P. & Laland, K. N. Trends Ecol. Evol. 28 , 712–718 (2013).

Langley, E. J., van Horik, J. O., Whiteside, M. A. & Madden, J. R. Anim. Behav. 142 , 87–93 (2018).

Wilson, D. S., Coleman, K., Clark, A. B. & Biederman, L. J. Comp. Psychol. 107 , 250–260 (1993).

Carducci, J. P. & Jakob, E. M. Anim. Behav. 59 , 39–46 (2000).

Thornton, A. & Lukas, D. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367 , 2773–2783 (2012).

van Praag, H., Kempermann, G. & Gage, F. H. Nature Rev. Neurosci. 1 , 191–198 (2000).

Thomson, J. A. & Heithaus, M. R. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 450 , 15–20 (2014).

Lehmann, M., Gustav, D. & Galizia, C. G. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65 , 205–215 (2011).

Vidal, J., Buwalda, B. & Koolhaas, J. M. Behav. Processes 88 , 76–80 (2011).

Magurran, A. E. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 353 , 275–286 (1998).

Budka, M., Matyjasiak, P., Typiak, J., Okołowski, M. & Zagalska-Neubauer, M. J. Ornithol. 160 , 673–684 (2019).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. PLoS Biol . 8 , e1000412 (2010).

Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J. & Ginges, J. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 11401–11405 (2018).

Simon, A. F. et al. Genes Brain Behav. 11 , 243–252 (2012).

Lalot, M., Ung, D., Péron, F., d’Ettorre, P. & Bovet, D. Behav. Processes 134 , 70–77 (2017).

O’Neill, S. J., Williamson, J. E., Tosetto, L. & Brown, C. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 72 , 166 (2018).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Supplementary Information

- Supplementary table and box

Related Articles

- Animal behaviour

- Research management

- Research data

Ligand cross-feeding resolves bacterial vitamin B12 auxotrophies

Article 08 MAY 24

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

Finding millennia-old ‘monumental’ corals could unlock secrets of climate resilience

Correspondence 07 MAY 24

Puppy-dog eyes in wild canines sparks rethink on dog evolution

News 05 MAY 24

Streamlined skull helps foxes take a nosedive

News & Views 03 MAY 24

‘Orangutan, heal thyself’: First wild animal seen using medicinal plant

News 02 MAY 24

Research Associate - Neural Development Disorders

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Staff Scientist - Mitochondria and Surgery

Recruitment of talent positions at shengjing hospital of china medical university.

Call for top experts and scholars in the field of science and technology.

Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

Faculty Positions at SUSTech School of Medicine

SUSTech School of Medicine offers equal opportunities and welcome applicants from the world with all ethnic backgrounds.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology, School of Medicine

Manager, Histology Laboratory - Pathology

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Comparative Psychology Explained

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Comparative psychology is the study of animals in order to find out about humans. The underlying assumption is that to some degree the laws of behavior are the same for all species and that therefore knowledge gained by studying rats, dogs, cats and other animals can be generalized to humans.

There is a long history of experimentation on animals and many new drugs and cosmetics were first tested on non-humans to see what their effects were. If there were no obvious harmful side effects then human trials would often follow.

In psychology, the method is often favored by those who adopt a nomothetic approach (e.g. Behaviorism and the biological approach ).

For example the behaviorists argued that the laws of learning were the same for all species. Pavlov’s (1897/1902) studies of classical conditioning in dogs and Skinner’s studies of operant conditioning in rats are therefore seen as providing insights into human psychology.

Some would even go so far as to claim that the results of such studies provide a justification for reorganizing the way in which we teach children in schools.

Another application of comparative psychology is in the study of child development . Konrad Lorenz and Harry Harlow are just two of the best-known researchers into the effects of maternal deprivation.

Lorenz (1935) studied imprinting in ducks and geese. He found that there was a critical period in infancy when the duckling would become attached and that if this window of opportunity were missed it would not become attached in later life.

Harlow (1958) found that infant rhesus monkeys that were separated from their mothers (and from all other monkeys) suffered irreversible social and emotional damage.

Many psychologists have argued that human infants also have a critical attachment period and that they too suffer permanent long-term damage if they are separated from their attachment figure.

In some respects humans are similar to other species. For example we exhibit territoriality, courtship rituals, a “pecking order”. We defend our young, are aggressive when threatened, engage in play and so on.

Many parallels can therefore be drawn between ourselves and especially other mammals with complex forms of social organisation.

Studying other species often avoids some of the complex ethical problems involved in studying humans. For example one could not look at the effects of maternal deprivation by removing infants from their mothers or conduct isolation experiment on humans in the way that has been done on other species.

Limitations

Although in some respects we are like other species in others we are not. For example, humans have a much more sophisticated intelligence than other species and much more of our behavior is the outcome of a conscious decision than the product of an instinct or drive.

Also humans are unlike all other species in that we are the only animal to have developed language. Whist other animals communicate using signs we use symbols and our language enables us to communicate about past and future events as well as about abstract ideas.

Many people would argue that experimenting on animals is completely ethically reprehensible. At least human subjects can give or withhold their consent. The animals used in some pretty awful experiments didn’t have that choice.

Also, what have we gained from all the suffering we have inflicted on these other species. Critics argue that most of the results are not worth having and that the ends do not justify the means.

Harlow, H. F. & Zimmermann, R. R. (1958). The development of affective responsiveness in infant monkeys. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 102,501 -509.

Lorenz, K. (1935). Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Der Artgenosse als auslösendes Moment sozialer Verhaltensweisen. Journal für Ornithologie, 83, 137–215, 289–413.

Pavlov, I. P. (1897/1902). The work of the digestive glands. London: Griffin.

Behaviorism

Animal research, does it help people is it any use otherwise.

Posted November 26, 2017

Three years ago, conservative TV and radio commentator Glenn Beck produced a short documentary called Socialized Science: The animal testing debate . (Subtitle: White-coat Waste ). The film has two themes. First, biomedical research with animals is a waste of money because it has no relevance to human beings. The second theme takes the form of repeated clips of suffering animals, mostly cute animals like baby chimps or puppies, as backing to narration or interviews with advocates and opponents of animal research. The conclusion is clear: research with animals is not only wasteful, but cruel and inhuman.

The film produced a reaction from the American Psychological Association and other professional groups associated with research using animals. Working scientists were urged to defend animal research. As an animal-experimenter, I responded to the request and submitted a commentary. No response. The silence of the requester seemed to be because I had some criticisms of research as well as of Mr. Beck.

The film’s first theme, that animal research is useless, is obviously false. Much of what we know about basic physiology of the heart, the lungs, the digestive system, infection and many others, would not have happened without research on live animals. But animal research in psychology, especially when framed in terms of direct human benefit, is often extrapolated beyond justifiable limits. The editor evidently disagreed, perhaps feeling that science should appear spotless. Hence my piece never saw the light of day. So here are some updated comments that are especially relevant now, when behavioral research with animals in psychology is under threat and much diminished compared to twenty or thirty years ago.

The focus of Beck’s film is on drug testing with ‘animal models’. Here there is a kernel of truth, much obscured by horrific intercuts of bloody carcasses and wounded dogs and monkeys. The general equivalence of animals and humans is indeed assumed by many. I have long been critical of the ‘animal model’ idea because it is too often taken literally. For scientific purposes the model is not the animal but the underlying process, be it circulation of the blood, source of infection or immune reaction. Only if the processes are identical in their essentials can the animal be a model for the human.

Sometimes the underlying physiology is different in humans and an animal model. I’m told that chocolate (contains theobromine) is bad for dogs. It’s not bad for me, though. An adequate understanding of the physiological differences between man and canine would show why. In other words, before you use an animal to test a drug, you need to know enough about its physiology to be sure that it will react in the same way as a human being. Otherwise, the study is just testing the human risks of chocolate with a dog model.

The animal-model idea has all too often degenerated into simple analogy. Once the phrase took hold, it became too easy to ignore the basic questions and just assume a simplistic equivalence between one species and another. Too much animal research has been of this sort. Unsurprisingly, through 2004 more than 90% of animal-tested drugs failed in clinical trials with humans.

A related issue is the continuing pressure to justify research by its human application. The tendency of government grantors to require practical justification – even for supposedly basic research and even though long-term effects are impossible to foresee – has only increased over the years. Uncritical acceptance of animal models has only encouraged this kind of claim, justified or not.

I grew up in Skinner’s operant lab at Harvard in the early 1960s. I wanted to know how animals learn, how reward schedules work and so on. My interest was to understand how pigeons adapted to reward, not to cure mental illness or improve primary schools. But Skinner’s interest was application – control of behavior. He extrapolated the results of a fledgling science not just to human behavior, but to the very design of human society. His unidimensional approach was taken seriously for many years. Maybe it still is, by some, although many of Skinner’s proposals are simplistic utopianism at best. Underpinning all is the idea that the pigeon is a model for the human in every significant respect.

Skinner was not alone in his scientific imperialism. The eclectic Berkeley learning theorist E. C. Tolman famously said many years ago “I believe everything important in psychology (except perhaps such matters as the building up of a super-ego, that is everything save such matters as involved society and words) can be investigated in essence through the continued experimental and theoretical analysis of the determiners of rat behavior at a choice point in the maze.” It is interesting that the (cognitive) behaviorist Tolman accepted the reality of the super-ego, a vaporous notion long discarded by science. And what of very human endeavors like art and fashion, not to mention moral issues – virtue and vice? How will the rat in a maze –or a pigeon in a Skinner box – help us with those? Tolman might have hesitated to answer. Skinner did not.

Most operant research is excellent, has told us much and could tell us much more. But the simplistic use many have made of it gets mixed reviews. We will have to go well beyond pigeons and rats before we have – if we will ever have – a true understanding of the springs of human action. Pigeons are not a model for humans. But just as the circulation of the blood occurs in both species, so similar principles, including those studied by operant conditioners may be studied in both. In other words it is not the pigeon that provides the model for humans, but the same underlying processes in both.

The animal-model idea has allowed too-ready extrapolation of incomplete science. The premature emphasis on human applicability has harmed not just animals but human beings. Teachers, therapists and planners place excessive confidence in supposedly science-based treatments and educational policies which are often based on little more than metaphor and weak analogy.

But Beck’s film misses on its key point, cost. In relation to the massive sources of real waste in the Federal government, the cost of biomedical science is trivial . People don’t do science for the money and don’t get rich as successful scientists. It is true that once you’re in, the pressure to get research grants, which may pay a little salary but mostly support the research and the institution, is strong. Nevertheless, the overall impact of science funding on the national budget is minute.

Beck’s movie is flawed. But one reason for its bad reception is flawed also: the fact that Beck produced it. The film must be bad because Mr. Beck made it. The genetic fallacy is to judge a claim by its source not its content. Many people demonize Mr. Beck and accuse him of lies, deceit and religious lunacy. Even some I respect, like the late Christopher Hitchens, followed this crowd. This film basically misses the point about animal research, but Mr. Beck does sometimes say things that are worth hearing, whether you agree with his political and religious views or not.

John Staddon, Ph.D. , is James B. Duke Professor of Psychology, and Professor of Biology and Neurobiology, Emeritus at Duke University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

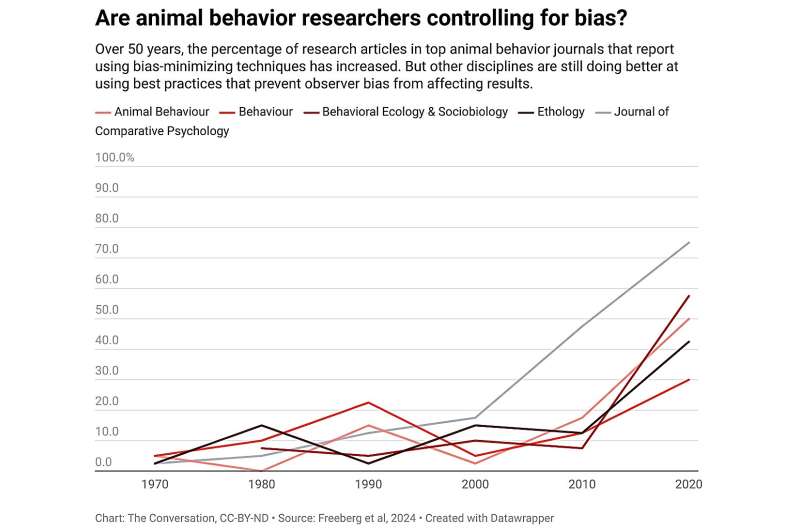

Animal behavior research is getting better at keeping observer bias from sneaking in – but there’s still room to improve

Professor and Associate Head of Psychology, University of Tennessee

Disclosure statement

Todd M. Freeberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Tennessee provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Animal behavior research relies on careful observation of animals. Researchers might spend months in a jungle habitat watching tropical birds mate and raise their young. They might track the rates of physical contact in cattle herds of different densities. Or they could record the sounds whales make as they migrate through the ocean.

Animal behavior research can provide fundamental insights into the natural processes that affect ecosystems around the globe, as well as into our own human minds and behavior.

I study animal behavior – and also the research reported by scientists in my field. One of the challenges of this kind of science is making sure our own assumptions don’t influence what we think we see in animal subjects. Like all people, how scientists see the world is shaped by biases and expectations, which can affect how data is recorded and reported. For instance, scientists who live in a society with strict gender roles for women and men might interpret things they see animals doing as reflecting those same divisions .

The scientific process corrects for such mistakes over time, but scientists have quicker methods at their disposal to minimize potential observer bias. Animal behavior scientists haven’t always used these methods – but that’s changing. A new study confirms that, over the past decade, studies increasingly adhere to the rigorous best practices that can minimize potential biases in animal behavior research.

Biases and self-fulfilling prophecies

A German horse named Clever Hans is widely known in the history of animal behavior as a classic example of unconscious bias leading to a false result.

Around the turn of the 20th century , Clever Hans was purported to be able to do math. For example, in response to his owner’s prompt “3 + 5,” Clever Hans would tap his hoof eight times. His owner would then reward him with his favorite vegetables. Initial observers reported that the horse’s abilities were legitimate and that his owner was not being deceptive.

However, careful analysis by a young scientist named Oskar Pfungst revealed that if the horse could not see his owner, he couldn’t answer correctly. So while Clever Hans was not good at math, he was incredibly good at observing his owner’s subtle and unconscious cues that gave the math answers away.

In the 1960s, researchers asked human study participants to code the learning ability of rats. Participants were told their rats had been artificially selected over many generations to be either “bright” or “dull” learners. Over several weeks, the participants ran their rats through eight different learning experiments.

In seven out of the eight experiments , the human participants ranked the “bright” rats as being better learners than the “dull” rats when, in reality, the researchers had randomly picked rats from their breeding colony. Bias led the human participants to see what they thought they should see.

Eliminating bias

Given the clear potential for human biases to skew scientific results, textbooks on animal behavior research methods from the 1980s onward have implored researchers to verify their work using at least one of two commonsense methods.

One is making sure the researcher observing the behavior does not know if the subject comes from one study group or the other. For example, a researcher would measure a cricket’s behavior without knowing if it came from the experimental or control group.

The other best practice is utilizing a second researcher, who has fresh eyes and no knowledge of the data, to observe the behavior and code the data. For example, while analyzing a video file, I count chickadees taking seeds from a feeder 15 times. Later, a second independent observer counts the same number.

Yet these methods to minimize possible biases are often not employed by researchers in animal behavior, perhaps because these best practices take more time and effort.

In 2012, my colleagues and I reviewed nearly 1,000 articles published in five leading animal behavior journals between 1970 and 2010 to see how many reported these methods to minimize potential bias. Less than 10% did so. By contrast, the journal Infancy, which focuses on human infant behavior, was far more rigorous: Over 80% of its articles reported using methods to avoid bias.

It’s a problem not just confined to my field. A 2015 review of published articles in the life sciences found that blind protocols are uncommon . It also found that studies using blind methods detected smaller differences between the key groups being observed compared to studies that didn’t use blind methods, suggesting potential biases led to more notable results.

In the years after we published our article, it was cited regularly and we wondered if there had been any improvement in the field. So, we recently reviewed 40 articles from each of the same five journals for the year 2020.

We found the rate of papers that reported controlling for bias improved in all five journals , from under 10% in our 2012 article to just over 50% in our new review. These rates of reporting still lag behind the journal Infancy, however, which was 95% in 2020.

All in all, things are looking up, but the animal behavior field can still do better. Practically, with increasingly more portable and affordable audio and video recording technology, it’s getting easier to carry out methods that minimize potential biases. The more the field of animal behavior sticks with these best practices, the stronger the foundation of knowledge and public trust in this science will become.

- Animal behavior

- Research methods

- Research bias

- STEEHM new research

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Study Notes

Animal Studies of Attachment: Lorenz and Harlow

Last updated 22 Mar 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

In the 1950s research which used animal subjects to investigate early life experiences and the ability for organisms to form attachments contributed significantly to the field of developmental psychology. Two of the most well-known animal studies were conducted by Konrad Lorenz and Harry Harlow.

Lorenz (1952)

Lorenz’s research suggests that organisms have a biological propensity to form attachments to one single subject.

Lorenz conducted an experiment in which goslings were hatched either with their mother or in an incubator. Once goslings had hatched they proceeded to follow the first moving object that they saw between 13 & 16 hours after hatching; in this case, Lorenz.

It supports the view that having a biological basis for an attachment is adaptive as it promotes survival.

This would explain why goslings imprint after a matter of minutes due to their increased mobility; human babies are born immobile and therefore there is less call for them to form an attachment straight away, and so, this develops later (8-9 months).

Harlow (1958)

Harlow conducted research with 8 rhesus monkeys which were caged from infancy with wire mesh food dispensing and cloth-covered surrogate mothers, to investigate which of the two alternatives would have more attachment behaviours directed towards it.

Harlow measured the amount time that monkeys spent with each surrogate mother and the amount time that they cried for their biological mother.

Harlow’s findings revealed that separated infant rhesus monkeys would show attachment behaviours towards a cloth-covered surrogate mother when frightened, rather than a food-dispensing surrogate mother. Monkeys were willing to explore a room full of novel toys when the cloth-covered monkey was present but displayed phobic responses when only the food-dispensing surrogate was present.

Furthermore, Harlow reviewed infant monkeys that were reared in a social (non-isolated) environment and observed that these monkeys went on to develop into healthy adults, while the monkeys in isolation with the surrogate mothers all displayed dysfunctional adult behaviour, including:

a) Being timid

b) Unpredictable with other monkeys

c) They had difficulty with mating

d) The females were inadequate mothers

Implications of Animal Studies of Attachment

The fact that the goslings studies imprinted irreversibly so early in life, suggests that this was operating within a critical period, which was underpinned by biological changes. The longevity of the goslings’ bond with Lorenz would support the view that, on some level, early attachment experiences do predict future bonds. The powerful instinctive behaviour that the goslings displayed would suggest that attachments are biologically programmed into species according to adaptive pressures; goslings innately follow moving objects shortly after hatching, as this would be adaptive given their premature mobility.

The rhesus monkeys’ willingness to seek refuge from something offering comfort rather than food would suggest that food is not as crucial as comfort when forming a bond. The fact that isolated monkeys displayed long-term dysfunctional behaviour illustrates, once more, that early attachment experiences predict long-term social development. Despite being fed, isolated monkeys failed to develop functional social behaviour, which would suggest that animals have greater needs that just the provision of food.

Evaluating Animal Studies of Attachment

Humans and monkeys are similar

Green (1994) states that, on a biological level at least, all mammals (including rhesus monkeys) have the same brain structure as humans; the only differences relates to size and the number of connections.

Important practical applications

Harlow’s research has profound implications for childcare. Due to the importance of early experiences on long-term development, it is vital that all of children’s needs are catered for; taking care of a child’s physical needs alone is not sufficient.

Results cannot be generalised to humans

It is questionable whether findings and conclusions can be extrapolated and applied to complex human behaviours. It is unlikely that observations of goslings following a researcher or rhesus monkeys clinging to cloth-covered wire models reflects the emotional connections and interaction that characterises human attachments.

Research is unethical

The use of animals in research can be questioned on ethical grounds. It could be argued that animals have a right not to be researched/ harmed. The pursuit of academic conclusions for human benefits could be seen as detrimental to non-human species.

- Types of attachment

- Explanations of Attachment: Learning Theory

- Ethical guidelines

You might also like

Caregiver-infant interactions in humans: reciprocity and interactional synchrony, example answer for question 12 paper 1: as psychology, june 2017 (aqa).

Exam Support

Example Answer for Question 18 Paper 1: AS Psychology, June 2017 (AQA)

Learning theory of attachment "holistic marking coach" activity.

Quizzes & Activities

Ethical Guidelines in Psychology - Classroom Posters or Student Handout Set

Poster / Student Handout

Attachment: Animal Studies of Attachment | AQA A-Level Psychology

Attachment: explanations for attachment (aqa psychology), attachment: bowlby's theory of maternal deprivation | aqa a-level psychology, our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

share this!

May 6, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

Animal behavior research better at keeping observer bias from sneaking in—but there's still room to improve

by Todd M. Freeberg, The Conversation

Animal behavior research relies on careful observation of animals. Researchers might spend months in a jungle habitat watching tropical birds mate and raise their young. They might track the rates of physical contact in cattle herds of different densities. Or they could record the sounds whales make as they migrate through the ocean.

Animal behavior research can provide fundamental insights into the natural processes that affect ecosystems around the globe, as well as into our own human minds and behavior.

I study animal behavior —and also the research reported by scientists in my field. One of the challenges of this kind of science is making sure our own assumptions don't influence what we think we see in animal subjects. Like all people, how scientists see the world is shaped by biases and expectations, which can affect how data is recorded and reported. For instance, scientists who live in a society with strict gender roles for women and men might interpret things they see animals doing as reflecting those same divisions.

The scientific process corrects for such mistakes over time, but scientists have quicker methods at their disposal to minimize potential observer bias . Animal behavior scientists haven't always used these methods—but that's changing. A new study confirms that, over the past decade, studies increasingly adhere to the rigorous best practices that can minimize potential biases in animal behavior research.

Biases and self-fulfilling prophecies

A German horse named Clever Hans is widely known in the history of animal behavior as a classic example of unconscious bias leading to a false result.

Around the turn of the 20th century , Clever Hans was purported to be able to do math. For example, in response to his owner's prompt "3 + 5," Clever Hans would tap his hoof eight times. His owner would then reward him with his favorite vegetables. Initial observers reported that the horse's abilities were legitimate and that his owner was not being deceptive.

However, careful analysis by a young scientist named Oskar Pfungst revealed that if the horse could not see his owner, he couldn't answer correctly. So while Clever Hans was not good at math, he was incredibly good at observing his owner's subtle and unconscious cues that gave the math answers away.

In the 1960s, researchers asked human study participants to code the learning ability of rats. Participants were told their rats had been artificially selected over many generations to be either "bright" or "dull" learners. Over several weeks, the participants ran their rats through eight different learning experiments.

In seven out of the eight experiments , the human participants ranked the "bright" rats as being better learners than the "dull" rats when, in reality, the researchers had randomly picked rats from their breeding colony. Bias led the human participants to see what they thought they should see.

Eliminating bias

Given the clear potential for human biases to skew scientific results, textbooks on animal behavior research methods from the 1980s onward have implored researchers to verify their work using at least one of two commonsense methods.

One is making sure the researcher observing the behavior does not know if the subject comes from one study group or the other. For example, a researcher would measure a cricket's behavior without knowing if it came from the experimental or control group.

The other best practice is utilizing a second researcher, who has fresh eyes and no knowledge of the data, to observe the behavior and code the data. For example, while analyzing a video file, I count chickadees taking seeds from a feeder 15 times. Later, a second independent observer counts the same number.

Yet these methods to minimize possible biases are often not employed by researchers in animal behavior, perhaps because these best practices take more time and effort.

In 2012, my colleagues and I reviewed nearly 1,000 articles published in five leading animal behavior journals between 1970 and 2010 to see how many reported these methods to minimize potential bias. Less than 10% did so. By contrast, the journal Infancy, which focuses on human infant behavior, was far more rigorous: Over 80% of its articles reported using methods to avoid bias.

It's a problem not just confined to my field. A 2015 review of published articles in the life sciences found that blind protocols are uncommon . It also found that studies using blind methods detected smaller differences between the key groups being observed compared to studies that didn't use blind methods, suggesting potential biases led to more notable results.

In the years after we published our article, it was cited regularly and we wondered if there had been any improvement in the field. So, we recently reviewed 40 articles from each of the same five journals for the year 2020.

We found the rate of papers that reported controlling for bias improved in all five journals , from under 10% in our 2012 article to just over 50% in our new review. These rates of reporting still lag behind the journal Infancy, however, which was 95% in 2020.

All in all, things are looking up, but the animal behavior field can still do better. Practically, with increasingly more portable and affordable audio and video recording technology, it's getting easier to carry out methods that minimize potential biases. The more the field of animal behavior sticks with these best practices, the stronger the foundation of knowledge and public trust in this science will become.

Provided by The Conversation

Explore further

Feedback to editors

New phononics materials may lead to smaller, more powerful wireless devices

9 hours ago

New 'forever chemical' cleanup strategy discovered

11 hours ago

TESS discovers a rocky planet that glows with molten lava as it's squeezed by its neighbors

Ultrasound experiment identifies new superconductor

12 hours ago

Quantum breakthrough sheds light on perplexing high-temperature superconductors

How climate change will affect malaria transmission

13 hours ago

Topological phonons: Where vibrations find their twist

Looking for life on Enceladus: What questions should we ask?

Analysis of millions of posts shows that users seek out echo chambers on social media

NASA images help explain eating habits of massive black hole

Relevant physicsforums posts, who chooses official designations for individual dolphins, such as fb15, f153, f286.

18 hours ago

Is it usual for vaccine injection site to hurt again during infection?

May 8, 2024

The Cass Report (UK)

May 1, 2024

Is 5 milliamps at 240 volts dangerous?

Apr 29, 2024

Major Evolution in Action

Apr 22, 2024

If theres a 15% probability each month of getting a woman pregnant...

Apr 19, 2024

More from Biology and Medical

Related Stories

Experiment reveals strategic thinking in mice

Apr 26, 2024

Can the bias in algorithms help us see our own?

Apr 9, 2024

AI depicts 3D social interactions between animals

Jan 9, 2024

Jurors recommend death penalty based on certain looks, but new training can correct the bias

Dec 14, 2023

Math teachers hold a bias against girls when the teachers think gender equality has been achieved, says study

May 3, 2023

Scientists believe studies by colleagues are more prone to biases than their own studies

Feb 3, 2021

Recommended for you

New rhizobia-diatom symbiosis solves long-standing marine mystery

16 hours ago

Genetic study finds early summer fishing can have an evolutionary impact, resulting in smaller salmon

Human activity is making it harder for scientists to interpret oceans' past

Discovery of ancient Glaswegian shrimp fossil reveals new species

Woodlice hold the new record for smallest dispersers of ingested seeds

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Chimps learn and improve tool-using skills even as adults, study finds

Prolonged learning capacity might be key to evolution of tool use in chimps and humans.

Chimpanzees continue to learn and hone their skills well into adulthood, a capacity that might be essential for the evolution of complex and varied tool use, according to a study publishing May 7 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Mathieu Malherbe of the Institute of Cognitive Sciences, France and colleagues.

Humans have the capacity to continue learning throughout our entire lifespan. It has been hypothesized that this ability is responsible for the extraordinary flexibility with which humans use tools, a key factor in the evolution of human cognition and culture. In this study, Malherbe and colleagues investigated whether chimpanzees share this feature by examining how chimps develop tool techniques as they age. The authors observed 70 wild chimps of various ages using sticks to retrieve food via video recordings collected over several years at Taï National Park, Côte d'Ivoire. As they aged, the chimps became more skilled at employing suitable finger grips to handle the sticks. These motor skills became fully functional by the age of six, but the chimps continued to hone their techniques well into adulthood. Certain advanced skills, such as using sticks to extract insects from hard-to-reach places or adjusting grip to suit different tasks, weren't fully developed until age 15. This suggests that these skills aren't just a matter of physical development, but also of learning capacities for new technological skills continuing into adulthood.

Retention of learning capacity into adulthood thus seems to be a beneficial attribute for tool-using species, a key insight into the evolution of chimpanzees as well as humans. The authors note that further study will be needed to understand the details of the chimps' learning process, such as the role of reasoning and memory or the relative importance of experience compared to instruction from peers.

The authors add, "In wild chimpanzees, the intricacies of tool use learning continue into adulthood. This pattern supports ideas that large brains across hominids allow continued learning through the first two decades of life."

- Learning Disorders

- Intelligence

- Educational Psychology

- Animal Learning and Intelligence

- Behavioral Science

- Jane Goodall

- Mental retardation

- Essential nutrient

- Evolution of the eye

- Sociobiology

Story Source:

Materials provided by PLOS . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Mathieu Malherbe, Liran Samuni, Sonja J. Ebel, Kathrin S. Kopp, Catherine Crockford, Roman M. Wittig. Protracted development of stick tool use skills extends into adulthood in wild western chimpanzees . PLOS Biology , 2024; 22 (5): e3002609 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002609

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Planet Glows With Molten Lava

- A Fragment of Human Brain, Mapped

- Symbiosis Solves Long-Standing Marine Mystery

- Surprising Common Ideas in Environmental ...

- 2D All-Organic Perovskites: 2D Electronics

- Generative AI That Imitates Human Motion

- Hunting the First Stars

- Kids' Sleep Problems Linked to Later Psychosis

- New-To-Nature Enzyme Containing Boron Created

- New Target for Potential Leukemia Therapy

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

COMMENTS

Animal research: a brief overview (PPT, 3.3MB) Animal research has provided numerous medical advancements and improvements in human and animal health. This slide deck, developed by members of the American Psychological Association (APA) Committee on Animal Research and Ethics (CARE), provides a brief overview of animal research in the United ...

The study of nonhuman animals has actually played a huge role in psychology, and it continues to do so today. If you've taken an introductory psychology class, then you have probably read about seminal psychological research that was done with animals: Skinner's rats, Pavlov's dogs, Harlow's monkeys. Unfortunately, many introductory ...

The Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition ® publishes experimental and theoretical studies concerning all aspects of animal behavior processes. Studies of associative, nonassociative, cognitive, perceptual, and motivational processes are welcome. The journal emphasizes empirical reports but may include specialized reviews appropriate to the journal's content area.

Comparative Psychology: Investigation of similarities and differences in multiple animal species—including humans—using techniques that encompass everything from observational studies in nature to neurophysiological research in the laboratory (Call et al. 2017; Tomasello and Herrmann 2010).. Cognition: Adaptive information processing in the broadest sense, from gathering information ...

The use of animal models in psychology research that is not of a neurobiological nature is quite rare in UK laboratories. This may lead many psychologists to consider the use of animals in scientific research as irrelevant to them. ... Beyond social psychology, animal studies have been of great importance in the increased understanding and ...

Materials and methods. We invited all researchers who are a first, last or corresponding author on any type of article published in the past three years (i.e., 2018-2020 inclusive) from the following six animal cognition journals to complete our survey: Animal Cognition, Animal Behavior and Cognition, Journal of Comparative Psychology, International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Journal ...

Research on animal cognition seeks to answer these questions to gain a better understanding of animal minds. This Collection welcomes submissions from the fields of comparative psychology and ...

A new framework for animal-behaviour research will help to avoid sampling bias — ten years on from the call to widen the pool of human participants in psychology studies beyond the WEIRD.

This article presents an overview of the definition and scope of what has come to be known as human-animal studies, a transdisciplinary field. The historical role and many contributions of psychology to it are examined, as is research from many related areas involved in this area of study. In addition, the emergence of clinically based research and practice involving animals, such as Animal ...

The study of animal behavior is a cornerstone of psychology for several reasons. ... (the study of animal behavior) and psychology. ... research aimed at proving whether the "Pet Effect" is ...

Oxytocin and HAI effects largely overlap, as documented by research in both, humans and animals, and first studies found that HAI affects the oxytocin system. As a common underlying mechanism, the activation of the oxytocin system does not only provide an explanation, but also allows an integrative view of the different effects of HAI.

Comparative psychology research shows that animals rely on behaviors that are most likely to help them deal with the environments around them. When researchers look at the "context" in which ...

a less forceful endorsement of animal research, Morris (1993) commented that "Some psychologists believe that since psychology is, at least in part, the science of behavior, animal behavior is just as interesting and important as human behavior" (p. 22). Ethical Issues in Animal Research Ethical issues in animal research were discussed in six of

A study of 8 leading introductory psychology textbooks indicated that with the exception of principles of conditioning and learning, the contributions of animal research to psychology were often ...

Psychological Research on Animals. The goal of psychological research is to understand human behavior and how the mind works. This involves studying non-human animals via direct observation and experimentation. Some of the experimental procedures involve electric shocks, drug injections, food deprivation, maternal separation or the manipulation ...

In the United States, laboratory research with nonhuman animals is strongly regulated by the federal government to ensure it is scientifically valid and that animals are treated humanely. Of course, it is also the ethical obligation of researchers and their institutions to appropriately care for animals. According to Sara Jo Nixon, PhD, chair ...

June 14, 2023. Reviewed by. Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc. Comparative psychology is the study of animals in order to find out about humans. The underlying assumption is that to some degree the laws of behavior are the same for all species and that therefore knowledge gained by studying rats, dogs, cats and other animals can be generalized to humans.

The film's first theme, that animal research is useless, is obviously false. Much of what we know about basic physiology of the heart, the lungs, the digestive system, infection and many others ...

A new study confirms that, over the past decade, studies increasingly adhere to the rigorous best practices that can minimize potential biases in animal behavior research.

Animal behavior research can provide fundamental insights into the natural processes that affect ecosystems around the globe, as well as into our own human minds and behavior. I study animal behavior - and also the research reported by scientists in my field. One of the challenges of this kind of science is making sure our own assumptions don ...

The Emergence of Animal Research Ethics. In his contribution to The Routledge Companion to Bioethics, Tom L. Beauchamp (2014, p. 262) calls animal research ethics "a recently coined term".It is, indeed, only in the last decade, that animal research has been discussed extensively within the framework of philosophical research ethics, but the term "animal research ethics" goes back at ...

Lorenz. Ethical guidelines. In the 1950s research which used animal subjects to investigate early life experiences and the ability for organisms to form attachments contributed significantly to the field of developmental psychology. Two of the most well-known animal studies were conducted by Konrad Lorenz and Harry Harlow.

The most obvious use is in research, including studies where animals are the primary subjects, for example there has been some growth in studies of the cognitive capacities of different species (e.g. dogs and horses). ... The majority of animal use in psychology is in research, and, if involving scientific procedures that may cause pain ...

Topics in Psychology. Explore how scientific research by psychologists can inform our professional lives, family and community relationships, emotional wellness, and more. ... but nonhuman animals are used as part of the study, such as research on the efficacy of animal-assisted interventions (AAI) and research conducted in zoos, animal ...

Animal studies are more properly known as "research involving non-human participants" and they play an important role in Psychology: from Pavlov's dogs and Skinner's rats to more recent studies involving the language abilities of apes, animals feature heavily in all the main approaches, but especially the Learning Approach. A research method where animals are observed in their natural ...

A new study confirms that, over the past decade, studies increasingly adhere to the rigorous best practices that can minimize potential biases in animal behavior research.

Objective. In previous animal studies, sound enhancement reduced tinnitus perception in cases associated with hearing loss. The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of sound enrichment therapy in tinnitus treatment by developing a protocol that includes criteria for psychoacoustic characteristics of tinnitus to determine whether the etiology is related to hearing loss.

The authors note that further study will be needed to understand the details of the chimps' learning process, such as the role of reasoning and memory or the relative importance of experience ...